Elisabetta Schiaroli, Giuseppe

Vittorio De Socio, Chiara Gabrielli, Chiara Papalini, Marco Nofri,

Franco Baldelli and Daniela Francisci.

Clinic of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, University of Perugia, Perugia, Italy.

Corresponding

author: Elisabetta Schiaroli, MD. Clinic of Infectious Diseases,

Department of Medicine, University of Perugia, Perugia, Italy, Hospital

"Santa Maria della Misericordia", Piazzale Menghini, 1 – 06156,

Perugia, Italy. Tel: +39-075-5784375 Fax: +39-075-5784346. E-mail:

elisabettask@libero.it

Published: March 1, 2020

Received: August 8, 2019

Accepted: February 14, 2020

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2020, 12(1): e2020017 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2020.017

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Background:

Despite progress in the prevention and treatment of HIV, persistent

issues concerning the evaluation of continuum in care from the

serological diagnosis to virologic success remains. Considering the

2020 UNAIDS target 90-90-90 for diagnosis, treatment, and viral

suppression of people living with HIV (PLWH), our purpose was to verify

if, starting from new diagnoses, the viral suppression rate of our

cohort of new PLWH satisfied the second and the third steps.

Methods:

This retrospective study regards all patients aged ≥15 undergoing HIV

test at our clinic between January 2005 and December 2017. We evaluated

the second and the third ‘90 UNAIDS targets and the unclaimed tests,

linkage to care, retention in ART, and the viral suppression at 1 and 2

years. Logistic regression (odds ratio, 95% confidence interval) was

performed.

Results: We

observed 592 new diagnoses for HIV infection: 61.4% on Italians, 38.5%

on foreigners. An antiretroviral treatment was started on 78.8% of the

new diagnoses (467/592) (second UNAIDS target), and a viral suppression

was obtained at 2 years on 82% of PLWH who had started ART (383/467)

(third UNAIDS target), namely only 64.7% of the new diagnoses instead

of the hoped-for 81% of the UNAIDS target. Logistic regressions

demonstrated that second and third ‘90 UNAIDS targets were unrelated to

sex, nationality, CD4 cells count, HIV-RNA and CDC stage (p>0.05).

The age class 25-50 years (OR=2.24; 95% CI = 1.06-4.37; p=0.04)

achieves more likely viral suppression when compared with patients

<25 years. Considering the continuum of care, 88 (15%) PLWH were

lost to engagement in care (55 unclaimed tests and 33 unlinked to

care), 37 didn’t start ART, 51 were LFTU at 2 years.

Conclusions:

UNAIDS goal was far to be reached. The main challenges were unreturned

tests as well as the retention in ART. Rapid tests for a test-treat

strategy and frequent phone communications in the first ART years could

facilitate UNAIDS target achievement.

|

Introduction

Despite

progress in the prevention and treatment of HIV, persistent issues

remain concerning continuum in care: late diagnosis, weak linkage, and

retention in care, limited engagement in therapy and/or treatment

adherence. To address these issues UNAIDS, in 2016, proposed the

“90-90-90" target (to ensure that 90% of people with HIV (PLWH) be

diagnosed, 90% of these be treated with ART, and 90% of those on ART

should achieve an undetectable viral load (VL).[1] The

continuum in care starts with HIV testing, progresses through to

linkage to care, retention in care, engagement in ART until achieving

sustained viral suppression, and then finishes with the maintenance of

the status.[2]

A systematic analysis of national

data showed that diagnosis (target one—90%) ranged from 87% (the

Netherlands) to 11% (Yemen). Treatment coverage (target two—81% on ART)

ranged from 71% (Switzerland) to 3% (Afghanistan). Viral suppression

(target three—73% virally suppressed) was between 68% (Switzerland) and

7% (China).[3] In Italy, in 2017, were reported 3.443

new HIV diagnoses, equaling an incidence of 5.7 per 100.000 residents.

HIV incidence in Italy is similar to the average incidence observed in

the European region (5.8 new cases x 100.000),[4] and it is estimated that 139.000 people are living with HIV and 11% of these are undiagnosed.[5]

Based on the results of a recent cohort study, 83% of patients are

linked to care and 87% of treated one’s achieved viral suppression.[6]

It

was estimated that in Italy, in 2017, 34.3% of people with a new HIV

diagnosis were from a foreign country. The proportion of foreigners

among new diagnoses has increased from 28.6% in 2010 to 34.4% in 2017.[4,5,7] However, in our region, Umbria, in 2017, the incidence of new diagnoses of HIV infection was 6.7 x 100.000 residents,[4] up to 40% of the new HIV diagnoses regarded foreign-born individuals in 2016-17.[8]

Foreigners are disproportionately affected by HIV compared to natives;

they still face barriers in attending the public health care system, in

initiating ART, and are at increased risk of virologic failure. This

type of risk is particularly high for unemployed and irregular

immigrants.[7]

Other studies on the continuum in

care about small Italian cohorts have found that risk factors for

un-retention and virological failure were: nationality, age, and CD4

cells counts.[9,10]

The aim of this retrospective

study was to compare 2005-2017 data collected at the Perugia Infectious

Diseases Clinic with the 2020 UNAIDS 90 targets for treatment and viral

suppression and to identify risk factors that could be associated with

failure to reach these targets.

Materials and Methods

Clinical Setting.

The Infectious Disease Clinic of Perugia follows about two thirds of

all Umbrian patients with HIV infection (PLWH), and at its day

hospital, it is possible to take the test for HIV infection anonymously

and free of charge. Moreover, in its laboratories, the confirmative

assay of all HIV positive screenings from the medical area around

Perugia is carried out; the medical staff of the Clinic personally

returns the positive results to facilitate a link to care and rapid

access to therapies. At the time of anonymous HIV screening, the

nursing staff is responsible for registering gender, age, and country

of origin of all test takers. For patients linked to care, data

regarding demographic issues, medical history, sexual behavior,

comorbidities, immune-virological profile, current medications and

other risk factors are inserted into an electronic database system

(NETCARE).

Data collection.

This retrospective study was performed compiling data from anonymous

nurse records and from NETCARE (only demographic issues,

immune-virological profile, current medications) in an excel file for

processing. All data up to 24 months of follow up for each patient were

collected. The study was approved by our local ethics committee on

June13th 2019 (protocol number 16566/19/ON) and according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Definitions.

We included all patients aged ≥15 undergoing an HIV test at our clinic

between January 2005 and December 2017. The following definitions were

used: Unclaimed Tests: HIV positive results not collected. Linked to care: patients attending one visit where blood samples are taken to determine the viral load and CD4+ T cell count. Retained in ART for one and two years: PLWH receiving therapy for one and two years. Virologic responder: HIV viral load < 50 copies/mL after 6 months of ART. Lost to Follow Up (LTFU): linked to care but subsequently lost to follow up.[11,12]

Primary outcomes.

-

Accordingly with the aim of the study, to compare observed 2020 UNAIDS

90 targets for treatment and viral suppression vs expected one, we

calculate:

- Proportion of patients treated at our clinic compared to all new diagnoses of HIV infection.

- Proportion of virologic suppressed patients one and two years after starting ART.

- The proportion of virologic suppressed

- Patients respect to the new diagnoses.

Secondary outcomes.

- We investigated factors that could be associated with failure to reach 2020 UNAIDS 90 targets.

- Proportion of patients with unclaimed tests,

- Proportion of patients linked to care,

- Proportion of patients retained in ART after two years.

Statistical analyses. Study design: retrospective mono center cohort study.

Categorical

variables were described as frequency (%, with a 95% confidence

interval, CI) and continuous variables were described as mean (±

standard deviation, SD). In the crude analysis, we used Pearson or

Mantel-Heaenzel chi square test (as appropriate) to assess the

association between categorical variables. Age at the diagnosis was

categorized into three levels (< 25, 25-50 and > 50-year olds)

using the stratum of < 25 as a reference category. CD4 cells was

also categorized into four class variables as <200, 200-350, 350-500

and >500 cells/mmc. Logistic regression (odds ratio, 95% confidence

interval) was used to account for differences among the groups when

comparing patients diagnosed that were on ART vs. patients who were off

ART, and patients on ART that were virally suppressed at 24 months vs.

unsuppressed and patients lost to follow-up. Variables included in the

analysis are: age strata, gender, nationality, CD4 cells count strata,

HIV-RNA, CDC stage.

Data analysis was conducted using the statistical software SPSS release 22.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago III).

Results

Characteristics of diagnosed subjects.

Between 2005 and 2017, 592 new diagnoses for HIV infection were made at

our laboratories: 364 on Italian-natives (61.4%), 228 on foreigners

(38.5%). Overall, 454 were men (30.3% foreigners), 138 women (65%

foreigners). The mean age was 40 (range 18-78), 9% were aged <25,

72.6% were aged 25-50 and 18.2% were aged > 50. Noteworthy,

foreigners were more numerous than Italians in the < 25 year olds

category (27 vs. 22), while they were very poorly represented over 50

(12 vs 104 subjects).

From diagnosis to ART: second “90”UNAIDS target.

Four hundred sixty-seven out of 592 (78.8%) PLWH started an ART. Out of

125 PLWH not treated, 88 (54 Italians and 34 foreigners) were lost to

engagement in care (55 didn’t withdraw the test, 33 didn’t attend the

first visit) and 37 didn’t start therapy. Of the 37 PLWH linked to

care, who didn’t start ART, 6 didn’t initiate ART within two years (all

before year 2009 and all with CD4 T cell counts > 350/mmc), 7 died

before, 3 moved to other centers, 1 was HIV-2 positive and 20 were lost

to follow up. Three out of the 20 LFTU were <25 year olds, 14 were

aged 25-50, 3 patients were over 50. Demographic characteristics of new

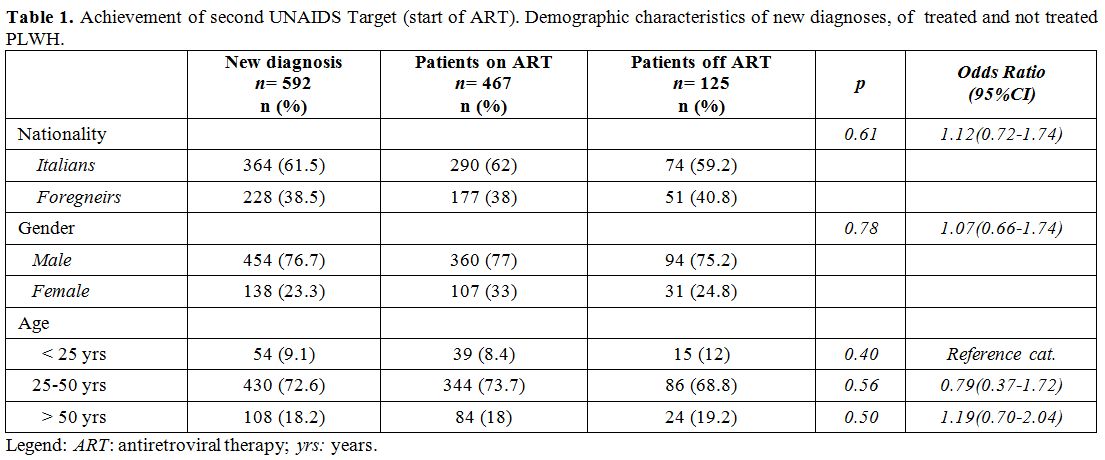

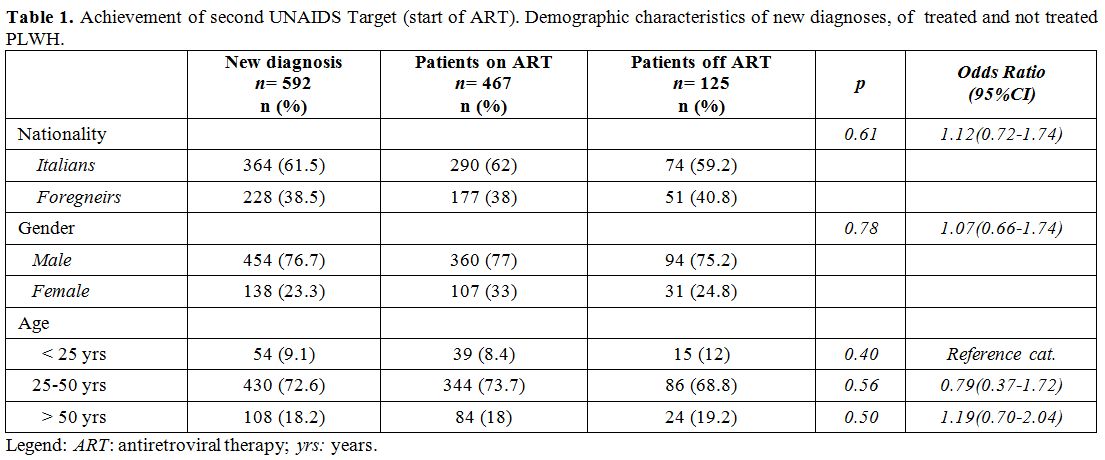

diagnoses, of treated and not treated PLWH are shown in Table 1. No significant differences between patients on ART and off ART for nationality, gender and age were observed (Table 1).

|

Table

1. Achievement of second UNAIDS Target (start of ART). Demographic

characteristics of new diagnoses, of treated and not treated PLWH. |

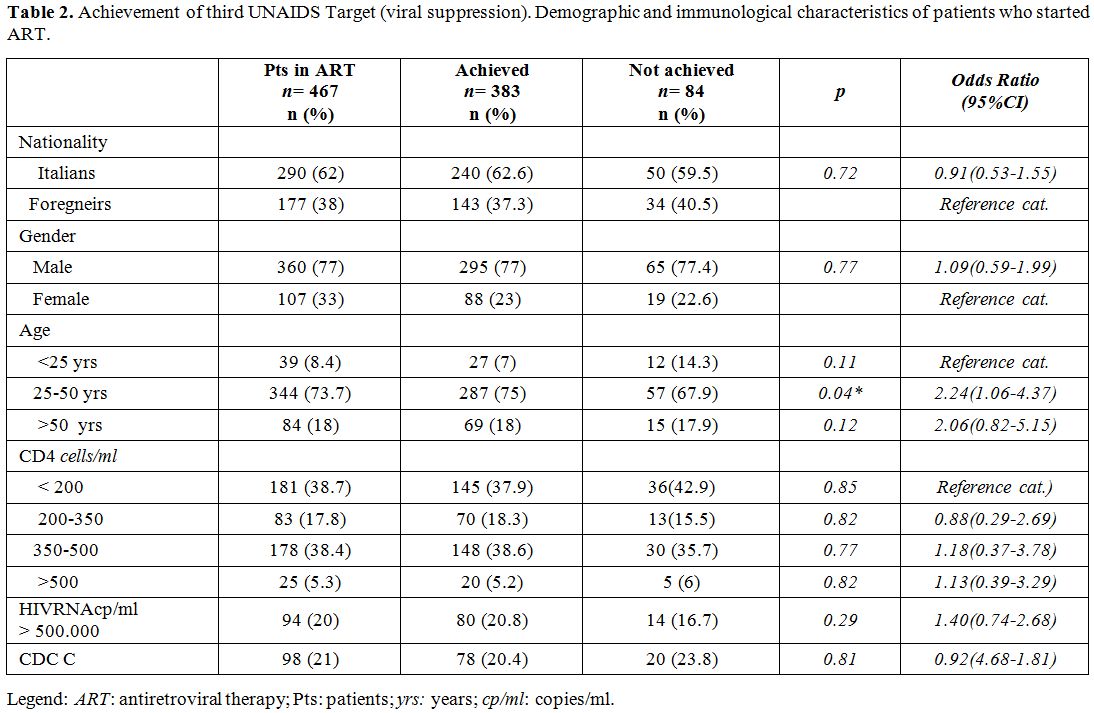

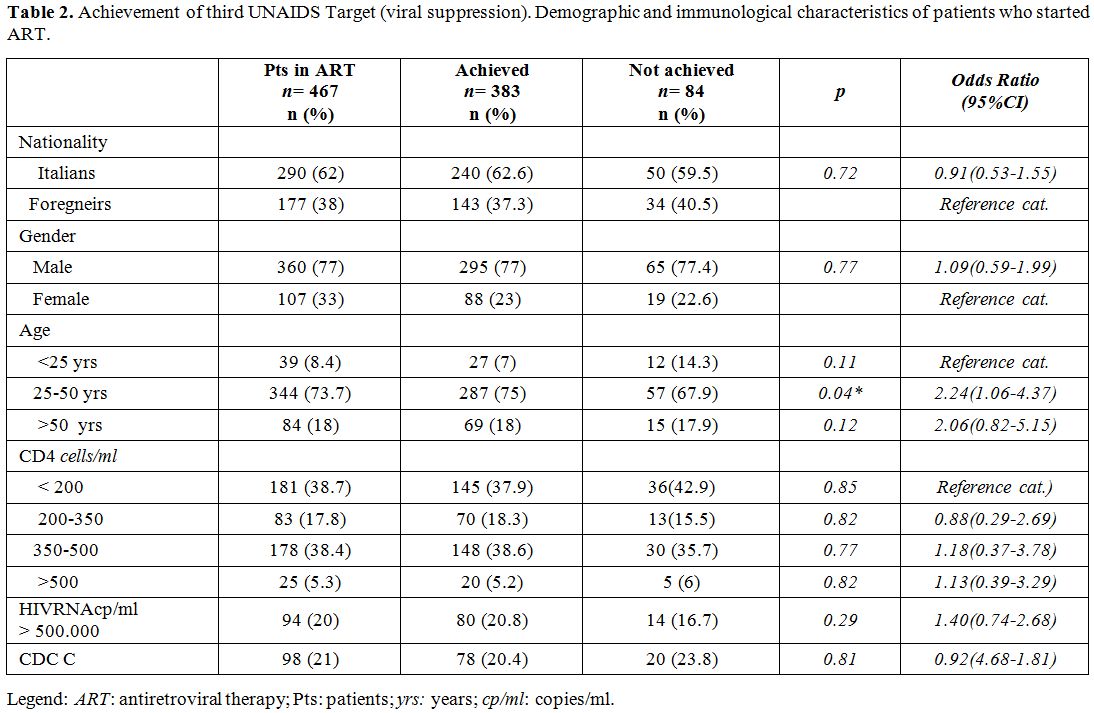

From ART to viral suppression: third “90”UNAIDS target.

An antiretroviral therapy was prescribed to 467 PLWH. The virologic

response at 12 and 24 months after starting ART was observed in 339

(72.6 %) and 383 (82%) patients respectively. Demographic and

immunological characteristics of PLWH starting ART, of whose achieving

or not the third UNAIDS target are reported in Table 2.

Logistic regressions demonstrated that second and the third ‘90 UNAIDS

targets were unrelated to sex, nationality, CD4 cells count, HIV-RNA

and CDC stage (p>0.05). The age class 25-50 years (OR=2.24; 95%

CI=1.06-4.37; p=0.04) achieves more likely viral suppression than

patients <25 years (Table 2).

|

Table 2. Achievement of

third UNAIDS Target (viral suppression). Demographic and immunological

characteristics of patients who started ART. |

Overall

64.7% patients were virally suppressed at 24 months respect to 592 new

diagnoses. At 24 months 51 PLWH were LTFU (32 within the first year),

33 didn’t achieve a sustained viral suppression. Considering only the

435 patients with available viral load at 12 months, a viral

suppression was obtained in 88% at 24 months.

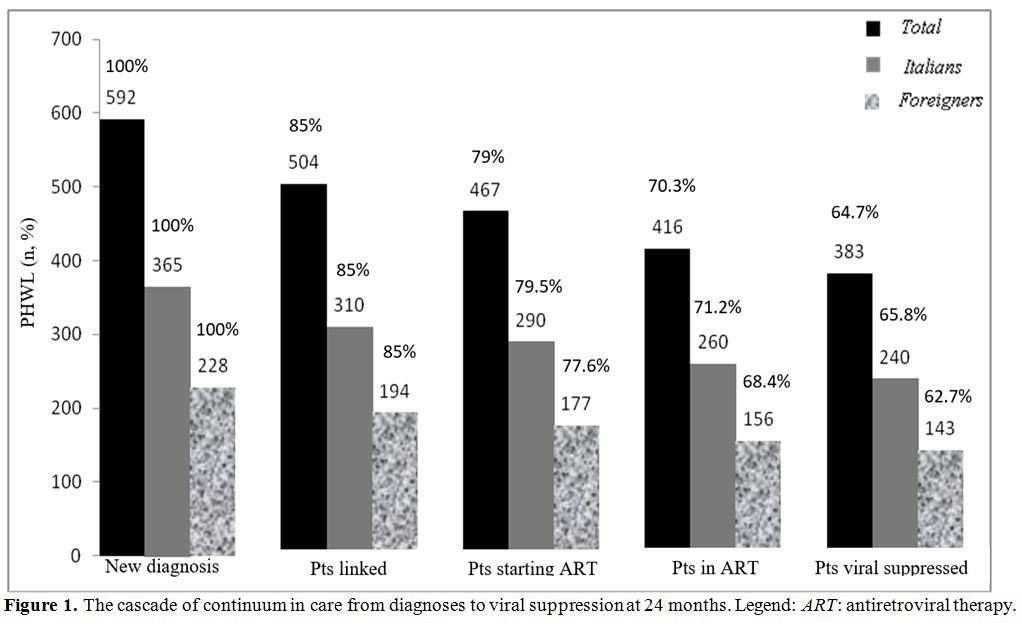

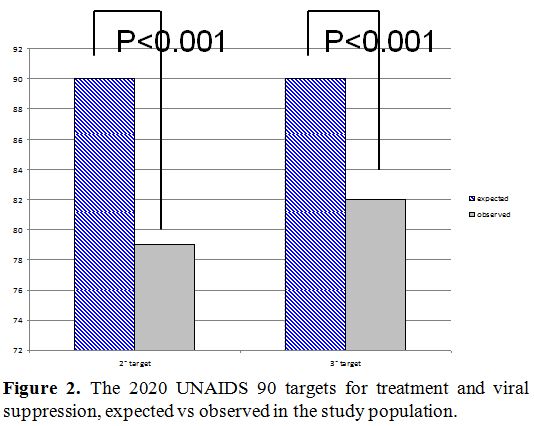

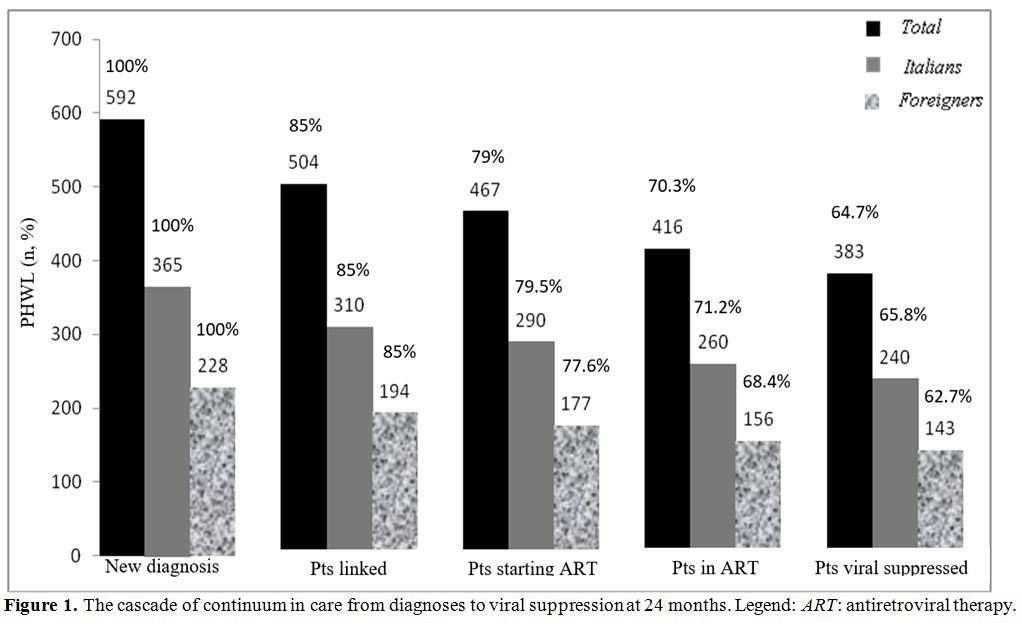

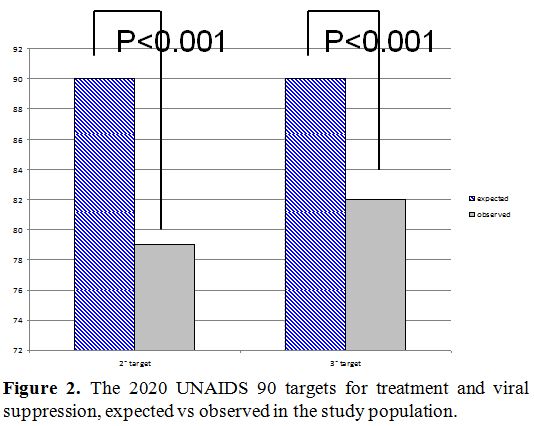

The cascade of

continuum in care from diagnoses to viral suppression in all patients

and in Italian and foreigners is illustrated in figure 1. Finally, we compared the observed UNAIDS target with the expected one, the result is shown in figure 2. The second and the third ‘90 UNAIDS targets obtained was significantly lower than expected (p<0.001).

|

Figure 1.

The cascade of continuum in care from diagnoses to viral suppression at 24 months. Legend: ART: antiretroviral therapy. |

|

Figure 2. The 2020 UNAIDS 90 targets for treatment and viral suppression, expected vs observed in the study population. |

True loss to follow up, and deaths.

Overall, we observed 64 PLWH true LTFU (20 before ART, 27 during the

first year and 27 in the second one), 6 PLWH moved to other centers (3

before ART) and 11 patients who died (7 before and 4 after ART), all

for malignancies. No differences were observed between Italians and

foreigners or gender or age classes neither in the withdrawal of the

test nor in the linkage to care (data not shown).

Discussion

Considering

the UNAIDS identified target 90-90-90 for 2020, the main characteristic

of our study was of being able to follow the entire clinical pathway of

PLWH from serological diagnosis to ART prescription, as well as to

virologic suppression (i.e., second and third target), given that for

the diagnosis of HIV infection all confirmatory tests from the medical

area of Perugia were carried out in our laboratories and positive

assays were always returned by our medical staff. Indeed, our

surveillance concerns a very high prevalence of foreign-born

HIV-infected subjects (38.5%), which significantly differs from general

national data: 17.3%[13] and from those reported in Genoa: 19%[9] and Florence: 27%[10]

experiences. In fact, other studies on the continuum in care have been

published in Italy about single hospital cohorts and, recently, from

the ICONA Foundation Study Cohort, all regarding the retention to care

and the virologic success on patients linked to care.[9,10,14]

In

this study, the UNAIDS goal was far to be reached; antiretroviral

treatment was started only on 78.9% of the new diagnoses (second 90

UNAIDS target) and viral suppression was obtained only on 82% of PLWH

who had started ART (third 90 UNAIDS target). Overall, only 64.7% of

the new diagnoses achieved sustained viral suppression instead of the

hoped-for 81% of the UNAIDS target (90% of the new diagnoses treated,

90% of treated under viral control).

The failure in achieving

the second target was partly determined by fifty five subjects who

didn’t claim the test, that is 9.2% despite being tested, 33 who didn’t

link to care (5.6%), and 20 who were true LTFU before starting ART

(3.96%). This is a very worrying data, indicative of a substantial

share of persistent undeclared or untreated. Indeed, excluding patients

not treated on the basis of contemporary guidelines, those who moved to

other centers and those who didn’t withdraw the results, the second

UNAIDS target was close to being reached (89.6%). The failure to

achieve viral suppression (third UNAIDS target) in our cohort regarded,

without any difference, both gender and nationality, unlike Prinapori

and Lagi[9,10] who observed that being foreign born

patients was statistically significant for failed retention in care.

Conversely, we observed, like Lagi[10] a higher risk of failure in achieving the third target for younger PLWH (Table 2).

The failure was not associated with ineffective drug regimens but,

instead, with a high LFTU on ART. Whether the analysis had been

performed from linkage to care, our results would have been in

agreement with the above studies. Prinapori reported a 75.8 %[9] and Lagi of 67.4%[10]

of virologic control compared to our 76% (383/504 PLWH linked). The

national data from the ICONA Foundation Study Group was very higher,

patients

from the ICONA cohort gave written informed consent to the study group

participation, thus effectively creating a bias in favor of retention

in ART compared to real life. Eventually, our virologic success in

retained patients (92.3%) was similar to the studies mentioned above

(97.6% and 95% respectively), but with a higher rate of foreign people

included. Regarding the durable viral suppression, it’s worthy of

consideration it was mainly achieved in the second year, although

without substantial changes in the proposed regimens, index of initial

inadequate adherence. Indeed, we observed a high rate of true LFTU

(excluding deaths) throughout the 24 months observation period, 64.5 x

1000 person-years and 39.1x1000 person-years in the first and second

year, respectively. These results require a clinical strategy aimed at

fostering the linkage to care and retention in ART.

In order to

improve the engagement in care, considering the anonymity and the

reluctance to provide a telephone number, we intend to activate a

test-treat strategy, particularly on vulnerable populations, in line

with the most recent World Health Organization (WHO) treatment

guidelines.[15] In addition to blood specimens drawn

for routine HIV test, we want to get a rapid HIV test on oral fluid and

then, if positive, to start ART immediately. The rapid test checks IgM

and IgG antibodies to HIV-1 and HIV-2 (sensitivity is 99.3%,

specificity is 99.8%)[16] and gets results within

30-40 minutes. Rapid ART could improve the uptake of the therapy by

reducing the number of LTFU from diagnosis to ART initiation[17,18]

and the spread of HIV infection. In this regard, the San Francisco

RAPID program addressed to vulnerable subjects might constitute a valid

example of interventions.[19] A rapid HIV test on oral fluid and immediate treatment can be useful strategies to improve the achievement of ART start.

Moreover,

to foster adherence we want to be focused on frequent health care

workers interactions and communications with PLWH by phone in agreement

with recent tips and advice,[20] focused not only on

the several aspects of ART but also on their wellbeing, in order to

achieve a higher virologic success and decrease the LTFU.

Strengths of our work are the follow up starting from serological diagnosis and the high prevalence of foreign born PLWH.

Limitations

are the limited number of subjects enrolled, the data collection from a

single clinical center, the absence of data about socio-economic

status, education, sex behavior, and about the follow up of PLWH moved

to other centers.

Conclusions

The

UNAIDS goal was far from being reached. The main challenges were

unreturned tests as well as the retention in ART, particularly for

younger PLWH. Rapid tests for a test-treat strategy and frequent phone

communications in the first ART years could facilitate UNAIDS target

achievement.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Stefano Ricci for his important editorial assistance.

References

- 90-90-90 An ambitious

treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. (https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/.../90-90-90_en_0.pdf)

UNAIDS / JC2684 (English original, October 2014).

- Yehia

BR, Stephens-Shields AJ, Fleishman JA, Berry SA, Agwu AL, Metlay JP,

Moore RD, Christopher Mathews W, Nijhawan A, Rutstein R, Gaur AH, Gebo

KA; HIV Research Network. The HIV Care Continuum: Changes over Time in

Retention in Care and Viral Suppression. PLoS One. 2015 Jun 18;10(6):e

0129376. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0129376

PMid:26086089 PMCid:PMC4473034

- Jacob

Levi, Alice Raymond, Anton Pozniak, Pietro Vernazza,Philipp Kohler,

Andrew Hill; Can the UNAIDS 90-90-90 target be achieved? A systematic

analysis of national HIV treatment cascades. BMJ Glob Health 2016 Sep

15;1(2):e000010. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2015-000010. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2015-000010

PMid:28588933 PMCid:PMC5321333

- Not Ist Super Sanità

2018;31(9, Suppl. 1):3-51

- Mammone

A, Pezzotti P, Regine V, Camoni L, Puro V, Ippolito G, Suligoi B,

Girardi E. How many people are living with undiagnosed HIV infection?

An estimate for Italy, based on surveillance data. AIDS. 2016 Apr 24;

30(7): 1131-1136. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000001034

PMid:26807973 PMCid:PMC4819953

- ICONA 2014 (http://www.fondazioneicona.org/_new).

- Saracino

A, Lorenzini P, Lo Caputo S, Girardi E, Castelli F, Bonfanti P, Rusconi

S, Caramello P, Abrescia N, Mussini C, Monno L, d'Arminio Monforte A.

Increased risk of virologic failure to the first antiretroviral regimen

in HIV-infected migrants compared to natives: data from the ICONA

cohort. ICONA Foundation Study Group. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016

Mar;22(3):288.e1-8.

- National HIV

Infection Diagnosis Surveillance System. Data from the Umbria Region,

20016-2017. (This work was carried out within the activities provided

in agreement and by the specific projects of Umbria Region, in

collaboration and with the scientific contribution of the Department of

Medicine).

- Prinapori R, Giannini B,

Riccardi N, Bovis F, Giacomini M, Setti M, Viscoli C, Artioli S, Di

Biagio A. Predictors of retention in care in HIV-infected patients in a

large hospital cohort in Italy. Epidemiol Infect. 2018

Apr;146(5):606-611 https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268817003107

PMid:29486818

- Lagi

F, Kiros ST, Campolmi I, Giachè S, Rogasi PG, Mazzetti M, Bartalesi F,

Trotta M, Nizzoli P, Bartoloni A, Sterrantino G. Continuum of care

among HIV-1 positive patients in a single center in Italy (2007-2017).

Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018 Nov 30;12:2545-2551. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S180736

PMid:30555224 PMCid:PMC6280894

- Kay

ES, Batey DS, Mugavero MJ.The HIV treatment cascade and care continuum:

updates, goals, and recommendations for the future. AIDS Res Ther. 2016

Nov 8;13:35. eCollection 2016. Review. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-016-0120-0

PMid:27826353 PMCid:PMC5100316

- Gardner

EM1, McLees MP, Steiner JF, Del Rio C, Burman WJ. The spectrum of

engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies

for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Mar

15;52(6):793-800. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq243. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciq243

PMid:21367734 PMCid:PMC3106261

- Camoni

L, Raimondo M, Urciuoli R, Iacchini S, Suligoi B, Pezzotti P; the

CARPHA Study Group. People diagnosed with HIV and in care in Italy in

2014: results from the second national survey. AIDS Care. 2018

Jun;30(6):760-764. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2017.1400639

PMid:29134815

- D'Arminio

Monforte A, Tavelli A, Cozzi-Lepri A, Castagna A, Passerini S,

Francisci D, Saracino A, Maggiolo F, Lapadula G, Girardi E, Perno CF,

Antinori A; Icona Foundation Study Group. Virological response and

retention in care according to time of starting ART in Italy: data from

the Icona Foundation Study cohort. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019 Dec 22.

doi: 10.1093/jac/dkz512. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkz512

PMid:31865395

- WHO guidelines on

HIV/AIDS.

- Parisi

MR, Soldini L, Vidoni G, Clemente F, Mabellini C, Belloni T, Nozza S,

Brignolo L, Negri S, Rusconi S, Schlusnus K, Dorigatti F, Lazzarin A.

Cross-sectional study of community serostatus to highlight undiagnosed

HIV infections with oral fluid HIV-1/2 rapid test in non-conventional

settings. New Microbiol. 2013 Apr;36(2):121-32.

- Pilcher

CD, Ospina-Norvell C, Dasgupta A, Jones D, Hartogensis W, Torres S,

Calderon,F, Demicco E, Geng E, Gandhi M, Havlir DV, Hatano H. The

effect of same day observed initiation of Art on HIV viral load and

treatment outcomes in a US public health setting. J Acquir Immune Defic

Syndr. 2017 Jan 1;74(1):44-51. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000001134

PMid:27434707 PMCid:PMC5140684

- Rosen

S, Maskew M, Fox MP, Nyoni C, Mongwenyana C, Malete G, Sanne I, Bokaba

D, Sauls C, Rohr J, Long L. Initiating antiretroviral therapy for HIV

at a patient's first clinic visit: the RapIT randomized controlled

trial. PLoS Med. 2016 Jun 3;13(6):e1002050 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002050

PMid:27258028 PMCid:PMC4892484

- Coffey

S, Bacchetti P, Sachdev D, Bacon O, Jones D, Ospina-Norvell C, Torres

S, Lynch E, Camp C, Mercer-Slomoff R, Lee S, Christopoulos K, Pilcher

C, Hsu L, Jin C, Scheer S, Havlir D, Gandhi M. RAPID antiretroviral

therapy: high virologic suppression rates with immediate antiretroviral

therapy initiation in a vulnerable urban clinic population. AIDS. 2019

Apr 1;33(5):825-832. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000002124

PMid:30882490

- Henny

KD, Wilkes AL, McDonald CM, Denson DJ, Neumann MS. A Rapid Review of

eHealth Interventions Addressing the Continuum of HIV Care (2007-2017).

AIDS Behav. 2018 Jan; 22 (1): 43-63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1923-2

PMid:28983684 PMCid:PMC5760442

[TOP]