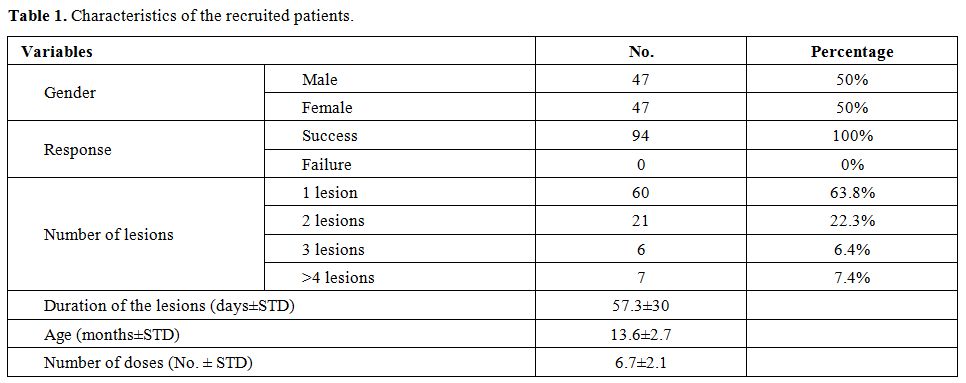

CL may lead to a disfigurement that causes mental, social, and emotional issues for children.[4,5] Early treatment is essential to prevent such disfigurement and related issues. In children, there are no clear guidelines to give an insight on how to choose medications, timing, and duration of the treatment of CL.[6] Most of the regimens used in the treatment of children are extrapolated from the efficacy and the safety data from adults.[6] The major part of the management of CL depends on the treatment by pentavalent antimony medications, including sodium stibogluconate. In adults, such medications are associated with toxicity that needs strict follow-up and frequent laboratory monitoring.[6] The efficacy and the safety of such medications have not been compiled in children, particularly under the age of two years.[6] This study aimed to investigate the efficacy and the safety of intralesional sodium stibogluconate regimens in pediatric patients under the age of two years with CL. The study protocol and informed consent were approved by the Research Ethics Committees of the College of Medicine, University of Zakho, Kurdistan Region, Iraq. Informed consent was obtained from legal guardians. Between August 2014 and September 2019, 104 patients with CL were recruited. Among those, ten patients were excluded because they did not follow the protocol of treatment, changed address before finishing treatment, or received treatment from more than one clinic and so they were excluded from further analysis. The mean age of patients was 13.6±2.7 months, and 47/94 (50%) were male.

60/94 (63.8%) of the patients presented with a single lesion (Table 1). The total number of lesions was 155, of which 51/155 (32.9%) lesion were nodular, and the rest were ulcerative lesions. In the first visit, recruited subjects did not receive treatment, and they were asked to return after four weeks. Then, the lesions were examined again, and if no signs of cure, then treatment was given. All patients were treated with intralesional infiltration of pentostam (Sodium stibogluconate, England). The treatment was given twice a week for a maximum of twelve sessions. Subjects were followed up for three months after the last treatment session. The outcome of the treatment was classified into a cure or failure. A cure was defined as reepithelization, wound healing, absence of inflammation, and complete resolution of induration. Treatment failure was defined as the presence of active inflammation and/or the appearance of new lesions. In a previous study investigating the cure rate of CL using intralesional sodium stibogluconate in children in India, 84.4% of patients were cured.[7] In a meta-analysis study reporting intralesional sodium stibogluconate cure rate in the pediatric age group, the overall treatment success rate was 75%.[6] It is worth mentioning that previous studies did not recruit children under the age of two years. Our study showed a success rate of 100%. It is acknowledged that this study was not a randomized clinical trial. However, we believe that a randomized clinical trial was very hard to do, considering the small number of patients coming in a long interval and the lack of infrastructure of such studies in our country. Clinical trials to be successful should have as background the right timing, communications, understanding, and motivations, particularly difficult to have in pediatric trials.[8] Furthermore, most of our subjects had fled war and lived in camps with poor conditions, and parents aimed to treat their children as soon as possible. Besides, we previously found difficulties in recruiting subjects in the control arm. These factors made conducting clinical trials insuperable in our region.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of the recruited patients. |

The high success rate should be interpreted cautiously, and parasite genotypes, and human genetic makeup should be considered. It is worth mentioning that because of this success rate, we could not study the effect of age, gender, number of lesions, and the duration of lesions on the treatment outcome. Then, we studied the factors influencing the number of doses required for the cure. In contrast to the previous reports that found a significant association between number lesions and number of doses,[9,10] no significant association was found between the number of doses and the number of lesions (p=0.088). No correlation was found between the number of doses and the duration of the lesion (p=0.48). No association was found between the number of doses and the age of the patients (p=0.79). Then, linear regression was utilized to investigate the relationship between gender or presence of livestock and the number of doses. No significant association was found between the gender and the number of doses (p=0.4; OR=1.08; OR=0; CI=0.89–1.31). In addition, no significant association was found between the presence of livestock and the number of doses (p=0.27; OR=1.13; CI=0.9–1.42). None of the patients warranted discontinuation of treatment because of the adverse effects, and no systemic side effects were reported in any patient. All subjects complained of pain at the site of injection. 90/94 (95.7%) of the subjects suffered from mild bleeding at the site of injection that was controlled by pressure using sterile gauze.

To conclude, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report recruiting children under the age of two years. Our findings showed that intralesional sodium stibogluconate resulted in a 100% cure rate. Intralesional sodium stibogluconate infiltration seems safe, effective, and well-tolerated with minimal adverse effects. Further studies, including clinical trials, are required to provide robust data on the efficacy and the safety of intralesional sodium stibogluconate leading to the development of clinical guidelines for the treatment of CL in this age group.