We here describe our results obtained in a retrospective monocentric experience with this approach focusing on extensive follow up after ASCT. In this study, the characteristic and the outcome of consecutive patients receiving ASCT in our department from 1992 to 2014 for AML was analysed. Patients affected by acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) were excluded from this analysis.

Sixty-seven patients were included in the study after approval from the Internal Review Board: 38 (57%) were males and 29 (43%) females, and the median age was 15 years (range 15-68). Cytogenetic analysis on bone marrow at diagnosis allowed to classify the population in 51/67 patients (76%) as follows: good risk group, bearing t(8;21)(q22;q22), inv(16)(p13q22)/t(16;16)(p13;q22); poor-risk group, bearing complex karyotype, inv(3)(q21q26)/t(3;3)(q21;q26)−5,-5q,−7,-7q, other abn(11q23), inv(3)(q21q26.2), t(3;3)(q21q26.2), t(6;9), t(9;22), abn(17p); intermediate-risk group, with cytogenetics abnormalities not encompassed in good or poor-risk group. Considering that this retrospective analysis encompasses 22 years, nucleophosmin (NPM1) was available in only 25 patients, and among them, 6 patients were NPM1+, and FLT3 mutational status was assessed only in 1 patient. Six (9%) out of 67 patients were in the good-risk group, 33 (49%) were in the intermediate group, 12 (18%) were in the high risk group, 7 (11%) were not evaluable for the absence of metaphases in the sample analysed and in 9 (13%) patients cytogenetic was not evaluated. Disease status at transplant was respectively: 1st complete remission (CR) in 57 patients (85%) and 2nd or 3rd CR in 4 patients (6%), partial remission (PR) in 4 (6%) and progressive disease (PD) in 2 (3%) patients. The median interval from diagnosis to ASCT was 6 months (range 3-37). The most common conditioning regimen was busulfan and cyclophosphamide administered in 52 patients (78%), but the combination of busulfan and melphalan was also used in 13 patients (19%) and BEAM in 2 patients (3%). The stem cell source was peripheral blood stem cells in all patients with a median dose of 4.1 x106/kg CD34+ (range 2.35-25.6).

Statistical analysis was performed using the NCCS11 package. Survival curves were estimated by the Kaplan-Meyer method, and the log-rank test was used for univariate comparison. The Gray test was used for univariate comparisons.

Two patients (4%) out of 67 patients died from transplant-related mortality mainly from infectious complications. Two patients transplanted with PD further progressed after autologous transplantation, the first had a central nervous progression and died 4 months after ASCT, the second one received allogeneic transplantation from a sibling donor, but relapsed and died 36 months after ASCT. Three patients receiving autologous transplantation in partial remission relapsed after a median of 3 months (range 1-5) and died at a median of 10 months (range 3-11) after ASCT. Only one patient receiving ASCT in PR relapsed and subsequently received allogeneic SCT and died from post-transplant EBV related malignancy.

Relapse was observed in 31 out of 57 patients transplanted in 1st CR (54%) at a median of 10 (range 1-152) months. Nine patients did not receive further treatment and died at a median of 2 months from relapse (range 1-3). A second attempt to induce 2nd CR was performed in 22 patients: 16 patients achieved 2nd CR either after low dose cytosine arabinoside based regimen or salvage chemotherapy. Seven patients achieving 2nd CR not proceeding to allogenic transplantation had a median survival of 42 months (range 17-68), and cause of death was AML in all patients. Eleven patients in 2nd CR went on to receive allogeneic stem cell transplantation as a salvage treatment, and 8 of them died from TRM at a median of 2.5 months (range 1-5) except for 2 patients who further progressed and died from the disease at 3 and 5 months respectively after allogeneic transplantation. One patient with a late relapse is currently alive and well at 29 months after allogeneic transplantation.

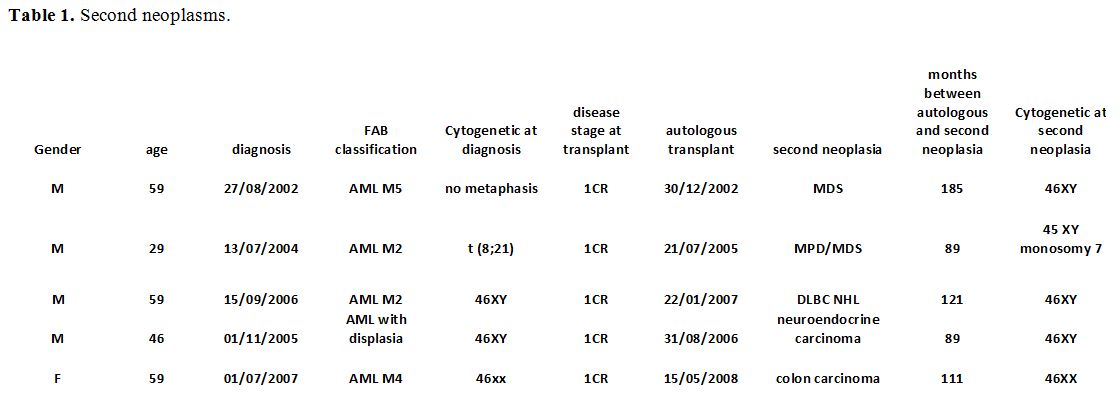

Twenty-seven patients remained in CR after ASCT at a median follow up of 173 (range 51-321) months. During extensive follow-up, 6 deaths not related to AML were recorded at a median of 85.5 months, and the cause of death was due to infection in 2 patients and secondary neoplasia in 2 patients and unknown in 2 patients, respectively. Interestingly, following a close follow up of long term survivors, we detected 5 out of 27 patients (18%) with a second neoplasm including 2 myelodysplastic syndromes unrelated to primary AML, one diffuse large B cell lymphoma of the rectum, 1 neuroendocrine carcinoma and 1 colon carcinoma at a median of 111 months (range 89-185 months) after ASCT (Table 1). Of them, three patients died from second neoplasia at 91, 98 and 119 months, respectively, 2 patients are alive at 157 and 205 months from ASCT.

|

Table 1. Second neoplasms. |

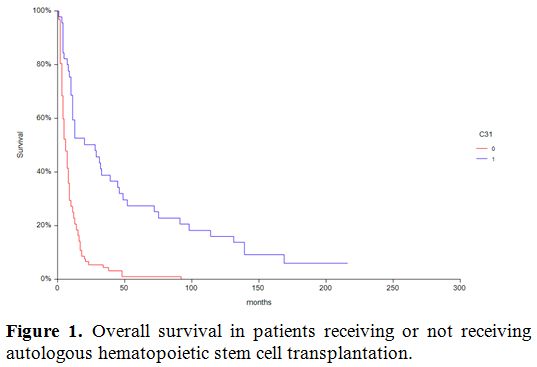

Overall Survival rate (OS) for all patients was 50% after a median follow-up of 51 months (1-321). OS rates were 66%, 63%, 48%, and 40% at 1, 2, 5, and 10 years respectively, and are reported in figure 1, as compared with our series of patients not transplanted. A landmark analysis for patients alive at 5 years after ASCT was performed, and the OS rate ten years was 68%.

|

Figure 1. Overall survival in patients receiving or not receiving autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. |

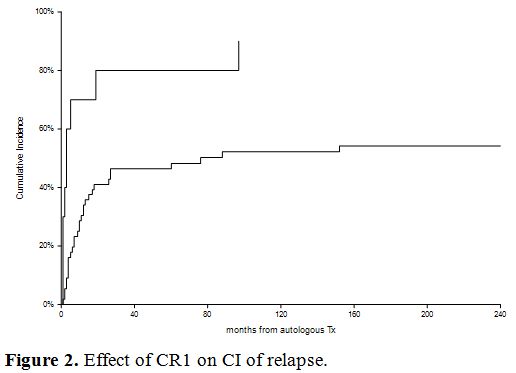

Cumulative incidence of relapse is depicted in figure 2 and was significantly different (p=0.009) in patients transplanted in 1st CR compared to patients in more advanced phase as the only variable since age, conditioning regimen, cytogenetic risk were not statistically significant in univariate analysis. Leukemia free Survival (LFS) rate for all patients was 59% at one year.

|

Figure 2. Effect of CR1 on CI of relapse. |

LFS rates were 51%, 46%, 39% at 2, 5 and 10 years respectively. The overall LFS rate in the population alive after five years from transplant was 73%.

Our findings demonstrate that nearly half of patients with AML are alive after five years post ASCT and that survivors after five years have an excellent OS and LFS. These data are similar to that been reported by Yanada et al.[3] in 2019. Salvage allogeneic transplantation remains feasible in those who relapse, but there is a very high TRM in our series, mainly due to the year of transplant carried out mainly more than ten years ago being reduced in the recent era.[4,5] ASCT, therefore, remains a reasonable option for patients with selected AML according to cytogenetic and molecular risk.[6] During extensive follow-up, which is rarely reported in the literature, new malignancies developed even in a subset of patients adhering to strict preventive measures and interestingly in 3 patients a new hematological malignancy occurred. Prospective risk-adapted approaches that assign patients to ASCT based on disease-risk and minimal residual disease (MRD) status are ongoing[7,8] and may clarify the specific subpopulations of AML patients who could take advantage of this currently neglected procedure.