Phakatip Sinlapamongkolkul1 and Pacharapan Surapolchai1.

1 Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Thammasat University, Thailand.

Correspondence to: Pacharapan Surapolchai, MD. Department of

Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Thammasat University, 99/209 Moo 18

Phaholyothin Rd, Khlongluang, Pathumthani, 12120, Thailand. Tel:

+6629269514. E-mail:

doctorning@hotmail.com

Published: July 1, 2020

Received: March 16, 2020

Accepted: June 3, 2020

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2020, 12(1): e2020036 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2020.036

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Background:

Thalassemia remains a challenging chronic disease in Thailand, but

national prenatal screening, along with better treatment and

management, may have improved health-related quality of life (HRQoL)

for pediatric patients. We aimed to measure the HRQoL of

transfusion-dependent (TDT) and non-transfusion dependent (NTDT) of

these pediatric patients at our institute.

Methods:

We included all patients 2 – 18 years old, with TDT and NTDT, using the

Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0 Generic Core Scales (PedsQL)

and the EuroQol Group's Five Dimensions for Youth (EQ-5D-Y)

instruments. Patients and caregivers responded as appropriate for age.

Results:

Mean PedsQL total summary scores (TSS) (SD) of child self-reports and

parent proxy-reports were 81.00 (10.94) and 78.84 (16.72) from 150

participants. Mean EQ-5D-Y VAS (SD) for children was 89.27 (11.56) and

86.72 (10.62) for parent proxies. The most problematic EQ-5D-Y

dimension was "having pain or discomfort”. These scores had

significant correlations between the child and parental proxy

perspectives, as well as between the PedsQL and EQ-5D-Y. An age of 8 -

12 years and oral chelation therapy predicted lower self-reported

PedsQL TSS. Parental proxy-report predictors for reduced PedsQL TSS and

EQ-5D-Y VAS were primary school education for children, parental proxy

secondary school education, Universal Coverage insurance, and TDT.

Conclusion:

HRQoL scores of our pediatric thalassemia patients had improved from

the previous decade, and these findings may represent our better

standard of care. Some sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

may present negative impacts on HRQoL. More exploration is needed to

understand predictors and further improve HRQoL, especially for TDT

patients.

|

Introduction

Thalassemia

is an inherited hemoglobin disorder in which alpha and beta-globin

genetic mutations decrease globin synthesis. It is highly prevalent in

Africa, the Mediterranean region, the Middle East, the Indian

subcontinent, and Southeast Asia:[1-3] 40-50% of the Thai population likely carries some sort of thalassemia gene.[4-5]

In 1993, the Thai government began screening pregnant women for three

severe forms: homozygous β-thalassemia, β-thalassemia/HbE disease, and

Hb Bart's hydrops fetalis.[5] Thalassemia has

varying severity from asymptomatic/mild anemia (thalassemia minor) to

severe (thalassemia major), the latter requiring lifelong blood

transfusions. Stem cell transplantation is the sole curative treatment[3]

but is reserved for only the most severe cases as it is expensive and

requires a direct family donor; thus, blood transfusions and iron

chelation remain standard treatments. Between 2013-4, the Thalassemia

International Federation (TIF)[6,7] created two

classification guidelines for the management of transfusion-dependent

thalassemia (TDT) and non–transfusion-dependent thalassemia (NTDT).

While this has resulted in improvements, complications from disease and

treatment persist, especially regarding iron overload.

Children

and adolescents with chronic illnesses also experience apprehension

about physical health, effects on growth and puberty, body image,

school absences, and disruption of social activities. Health-related

quality of life (HRQoL) is a measure of how well patients can

participate in a lifestyle typical for their age.[8,9] Before TIF guidelines implementation, thalassemia patients reported suboptimal HRQoL, associated with disease severity.[10,11] The Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0 Generic Core Scales (PedsQL) is well known and easy to score.[12] Previous research in Thailand demonstrated that healthy children had significantly higher mean HRQoL scores[13] to chronically-ill ones in all PedsQLsubscales. The EuroQol Group's Five Dimensions for Youth (EQ-5D-Y)[14]

is another tool to evaluate child and adolescent HRQoL; the

questionnaire layout may be more child-friendly. Both instruments have

Thai versions with adequate reliability and validity.

While

there is a large global body of research on HRQoL for pediatric

thalassemia patients, not much has been done in Thailand. In

2015, a Thai study of adolescents with thalassemia reported higher

serum ferritin levels, and comorbidities were associated with lower

HRQoL.[15] We previously published a report from our hospital (2010) with 2008-9 data,[16]

using the PedsQL with 75 pediatric patients and found that family

finance and disease severity affected HRQoL outcomes. Somewhat

similarly, recent studies from Egypt and Sri Lanka noted comorbidities

(short stature, splenectomy, and undernutrition), transfusion

dependence, and lower patient and mother educational levels as

associated with lower HRQoL scores.[17,18]

As of

2019, our hospital has a broader patient demographic,

better-established treatment guidelines, and improved access to

pediatric endocrinology and cardiology staff. Our objectives were

to assess HRQoL among children and adolescents with thalassemia using

both the PedsQL and EQ-5D-Y and examine possible factors affecting

HRQoL. We also wanted to determine if improvements occurred in

thalassemia management that impacted HRQoL and observe outcome

discrepancies for TDT versus NTDT patients.

Methods and Materials

Participants.

The clinical and socioeconomic data of TDT and NTDT patients receiving

treatment at our institute, aged 2 - 18 years old, were collected from

outpatient records and patient files at the Pediatric Hematology

Clinic, Thammasat University Hospital from June 2019 to December

2019. Our study protocol was approved by the Human Ethics

Committee of Thammasat University No. 1 Faculty of Medicine; assent

and/or informed consent forms were obtained from patients > 7 years

old and all parents or guardians. Patients and parents/guardians who

did not speak or understand Thai adequately were excluded as were cases

with incomplete history or records.

Growth assessment.

Anthropometric measurements, including weight, height and body mass

index (BMI), were recorded. Z-scores or standard deviation (SD) scores

of BMI for age were calculated using WHO Anthro and AnthroPlus

software.[19,20] BMI Z-scores (BMIZ) < 2 standard

deviations (SD), > 1, and > 2 SD were categorized as underweight,

overweight, and obese, respectively.

Measurement of HRQoL.The

validated Thai versions of the PedsQL and the EQ-5D-Y questionnaires

were used to assess pediatric HRQoL. The corresponding user agreement

was signed with MAPI Research Institute, Lyon, France, prior to using

the PedsQL, and our research was registered at the EuroQol Research

Foundation for the EQ-5D-Y. Questionnaires were either completed

independently by parent proxies or patients as possible; for very young

patients, the questions were given as an interview and forms filled out

by research assistants.

The PedsQL has forms for different stages of development per age groups: 2 - 4, 5 - 7, 8 - 12, and 13 - 18 years.[8,9,12]

All forms have four sections on physical health (8 items), emotional

wellbeing (5), social interaction (5), and/or school (5). All this

makes up an 8-item physical health summary score (PHS) and a 15-item

psychosocial health summary score (PCHS). Parallel child self-reports

and parental proxy-reports were filled out for each age group, except

for children 2 - 4 years old, which had only parental proxies. Possible

responses to each item were coded 0 to 4, i.e., never to almost always.

The child self-report form for the 5 - 7 years old group has a

three-point scale instead of five: not at all, sometimes, and a lot.

For children 2 - 4 years old not attending kindergarten, daycare, etc.,

the school section was omitted; if these children were attending some

form of school, parent proxies had to complete only three items in this

section.

The EQ-5D-Y is a two-part tool

to be completed by all parents/guardians as well as children aged 8 -15

years old. We extended this tool to the age of 18 years, as recommended

by the original developer, in order to have only one EQ-5D version in

this study.[14,21] The first

section has five questions on "mobility" "looking after myself" "doing

usual activities" "having pain or discomfort," and "feeling worried,

sad or unhappy". There are three possible answers to each question: no

problem, some/moderate problem/s, a lot of/severe problem/s. In the

last section of the EQ-5D-Y, participants indicate the current level of

health on a visual analog scale (VAS) from 0 to 100, 100 being highest

or best.

Statistical analysis.

Data were expressed as mean (SD; the standard deviation of the mean),

range, or percentage (%). Differences in variables between groups were

analyzed by t-test, Mann-Whitney U test, or ANOVA for continuous

variables and by Chi-square or Fisher's Exact tests for categorical

variables as appropriate. Internal reliability was assessed with

Cronbach's alpha for summary and total scores of the PedsQL and

EQ-5D-Y. We used Pearson's or Spearman's rank correlation coefficients

as appropriate to examine the strength of the relations between

preference values. Univariate or multivariate stepwise linear

regression analysis was undertaken to identify independent predictors

of HRQoL. All analyses incorporated Microsoft Excel 2019 and SPSS for

Windows (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 17.0, SPSS

Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All p-values were two-tailed: p < 0.05 was

considered statistically significant.

Results

We

had 150 patients with TDT and NTDT. All children and their guardians

(including 94 mothers, 35 fathers, 15 grandmothers, one grandfather,

and five other relatives) completed the PedsQL and EQ-5D-Y as

appropriate. All children > 8 years old completed the EQ-5D-Y (85

participants); 121 children > 5 years responded to the PedsQL, as

expected.

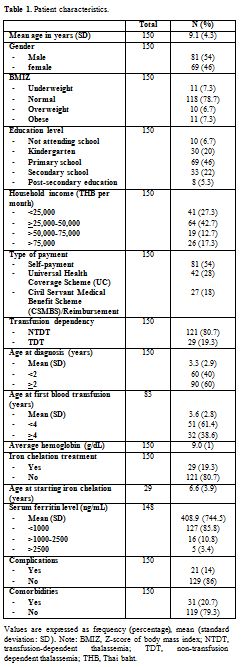

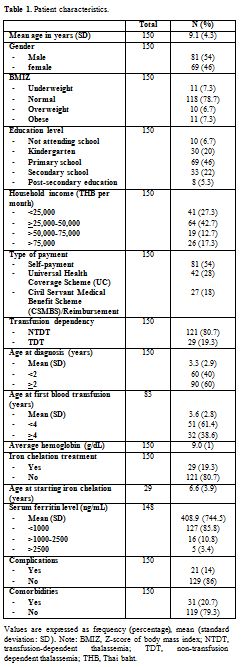

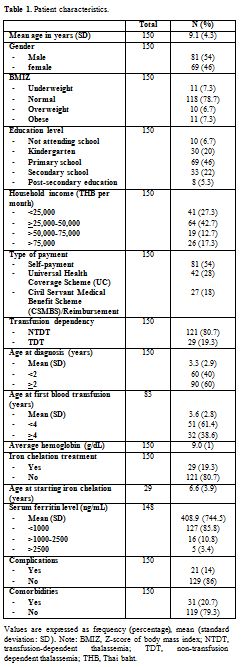

Patient characteristics. The demographic and clinical characteristics of all children are given in Table 1.

There was a mean age of 9.1 years (SD 4.3, range 2-18.8 years), with 81

males (54%). Most had normal nutritional status, i.e., normal BMIZ, and

were studying in primary school. Within the total, 3 had β thalassemia

major, 42 with β thalassemia/Hb E, 56 with Hb H disease (with/without

Hb Constant Spring [CS]/Hb Pakse [PS]), 25 with AE Bart's disease

(with/without Hb CS/Hb PS), 2 with EF Bart's disease (with/without Hb

CS), 16 with homozygous Hb E disease, and 6 having homozygous Hb CS

disease.

|

Table 1. Patient characteristics. |

Almost 20% (19.3%)

were TDT (three with β thalassemia major, 21 with β thalassemia/Hb E, 2

with Hb H disease, 3 with AE Bart's disease (with/without Hb CS/Hb PS),

all receiving iron chelation therapy regularly. Around 55% (55.17%) of

the patients (16/29) were receiving deferiprone (DFP), only one patient

receiving deferasirox (DFX), and 12/29 were receiving combination

therapy: eight with deferoxamine (DFO)+DFP and four with DFO+DFX.

The

mean age (SD) at diagnosis, at first blood transfusion, and at starting

iron chelation was 3.3 (2.9) years (range 0.1- 15 years), 3.6 (2.8)

years (range 0.1 - 15 years), and 6.6 (3.9) years (range 2-17.7 years),

respectively. Only 21 patients (14%) had complications, mostly

endocrinal diseases, including vitamin D deficiency (14 patients),

adrenal insufficiency (three), and short stature or growth failure

(three). Hypogonadism, hypothyroidism, or hypoparathyroidism was not

found in our participants. We screened for pulmonary hypertension

only in TDT, NTDT with iron overload, and splenectomy patients due to

hospital protocol; we had no cases of pulmonary hypertension. There was

one case of gallstones. In the 20.7% of total patients with some sort

of comorbidity, 45.2% suffered from allergic diseases, including seven

cases of allergic rhinitis, four cases of asthma, and three cases of

asthma with allergic rhinitis (data not shown).

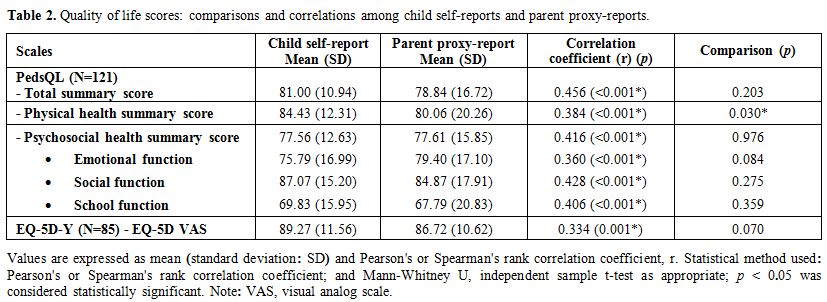

HRQoL scores comparisons and correlations.

The reliability of the PedsQL and EQ-5D-Y was very acceptable with

Cronbach's alpha values > 0.7 (0.925 and 0.863, respectively).

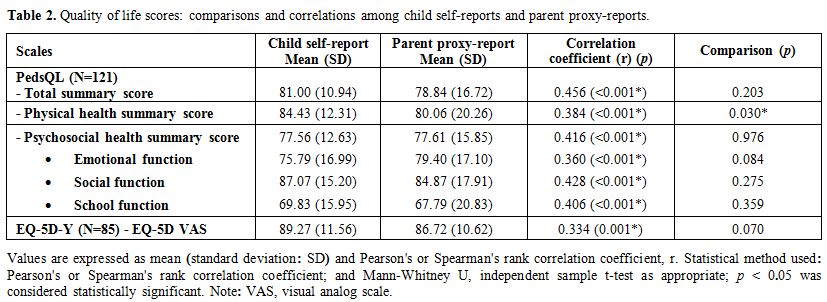

All mean (SD) scores for PedsQL and EQ-5D-Y self-reports, as well as

proxy-reports, are seen in Table 2.

|

Table

2. Quality of life scores: comparisons and correlations among child self-reports and parent proxy-reports. |

Quality of life

scores were shown to have significant correlations between child self

and parental proxy reports for both PedsQL and EQ-5D-Y. For mean

PedsQL scores (SD), children's self-reports were slightly higher than

parental proxies for two categories: total summary score (TSS) and PHS;

only PHS was significantly different (p

= 0.030), the others not being statistically significant. PCHS child

and parental proxy reports were practically identical. EQ-5D-Y VAS

showed a statistically significant correlation with the PedsQL TSS of

both self-reports and proxy-reports: (r = 0.344, p = 0.001 and r = 0.271, p

= 0.001, respectively). In addition, the EQ-5D-Y dimensions revealed

statistically significant correlations with the PedsQL of both

self-reports and proxy-reports. Significant relationships were found

between the EQ-5D-Y dimensions of "mobility" "looking after myself" and

"doing usual activities" with PedsQL PHS scores (r = -0.220 and -0.171;

-0.477 and -0.138; -0.401 and -0.183: for self- and proxy-reports,

respectively). Moderate correlations were also seen between the EQ-5D-Y

dimensions of "having pain or discomfort" and "feeling worried, sad or

unhappy" with the PedsQL PCHS scores (r = -0.271 and -0.254; -0.381 and

-0.274: for self- and proxy-report, respectively). Please see Supplementary Table 1.

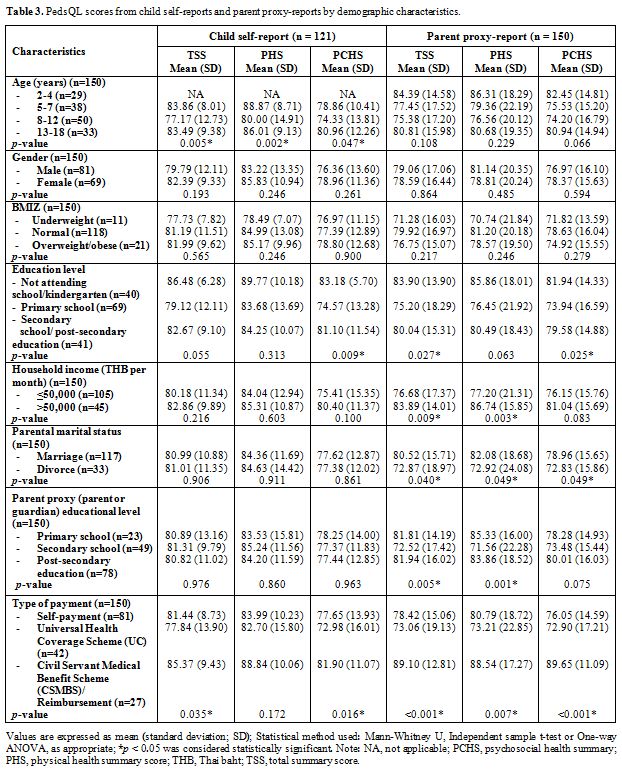

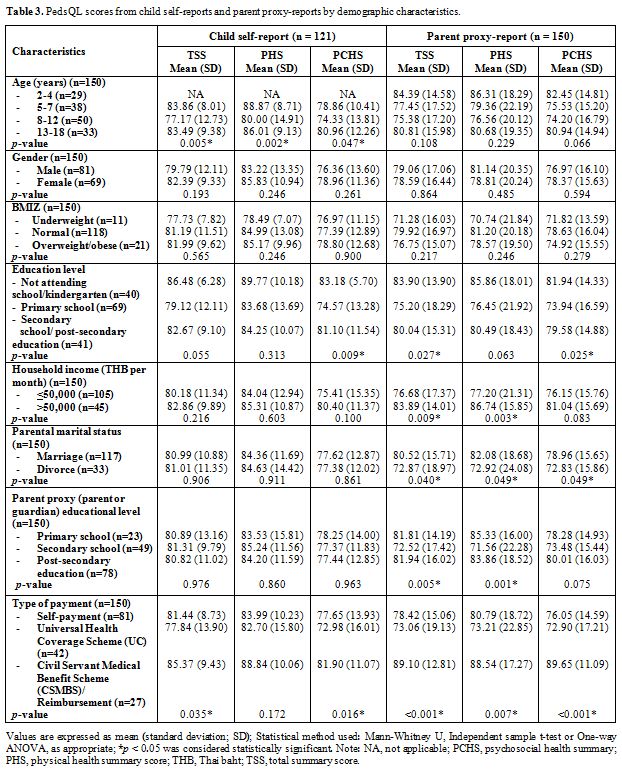

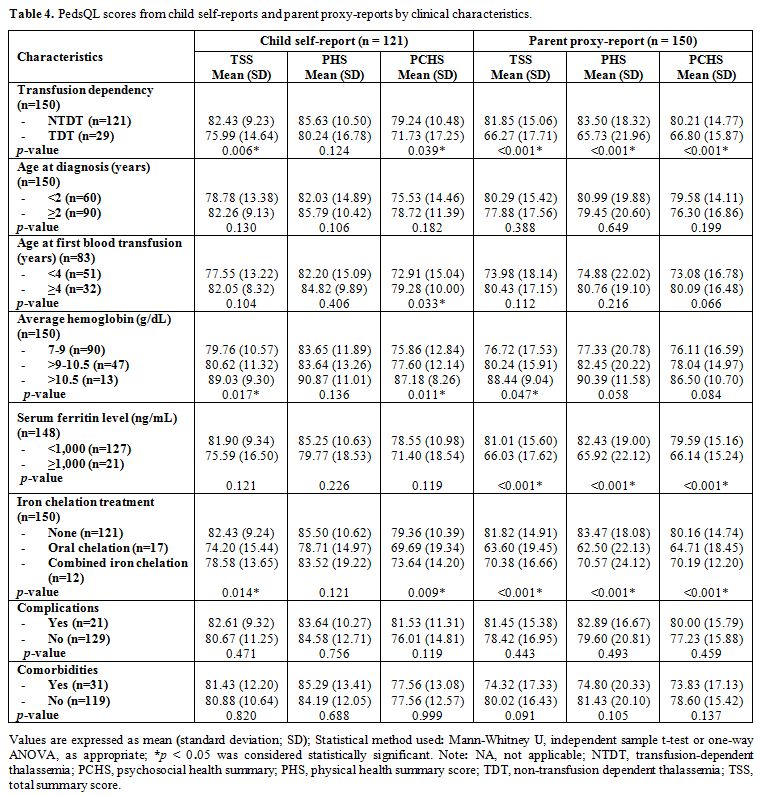

HRQoL scores and related factors. PedsQL child self-report and parent proxy-report scores along with patient demographic and clinical characteristics are in Table 3 and 4. Age group and type of payment demonstrated significant differences within self-reported TSS (p

= 0.005 and 0.035). For parental proxy reports, child education level,

parental marital status, household income, parent proxy education, and

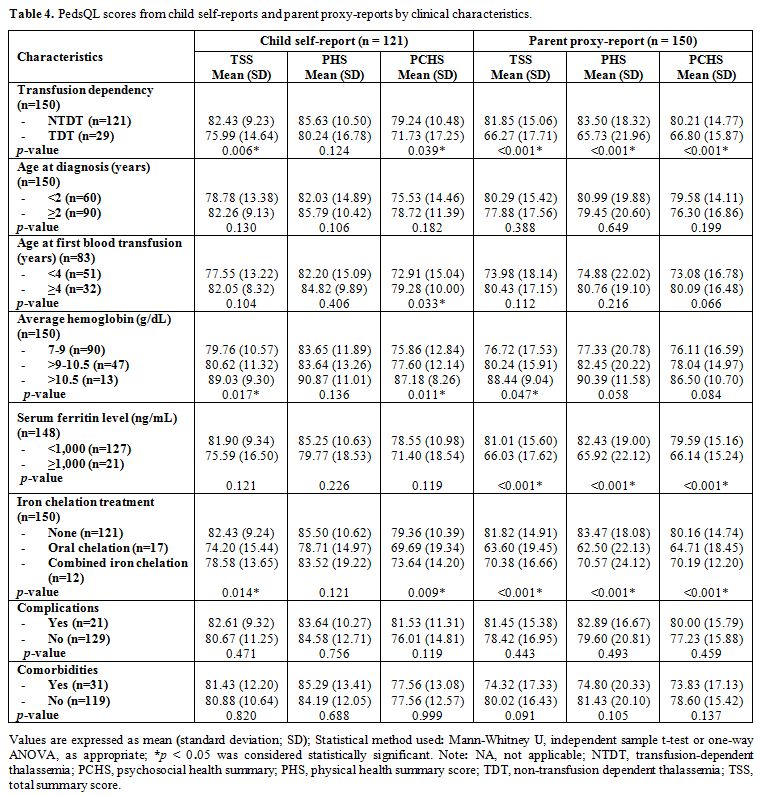

type of payment revealed significant differences in TSS (p = 0.027, 0.040, 0.009, 0.005 and < 0.001, respectively) in Table 3. Being TDT or NTDT, average Hb, and having iron-chelation therapy were all significantly related to self-reported TSS (p = 0.006, 0.017, and 0.014, respectively), as indicated in Table 4.

In addition, transfusion dependency, average Hb, ferritin level and

iron-chelation therapy were also associated with parental proxy TSS (p = < 0.001, 0.047, < 0.001, and < 0.001, respectively); these patients typically had lower self-assessed HRQoL scores.

|

Table 3. PedsQL scores from child self-reports and parent proxy-reports by demographic characteristics. |

|

Table 4. PedsQL scores from child self-reports and parent proxy-reports by clinical characteristics. |

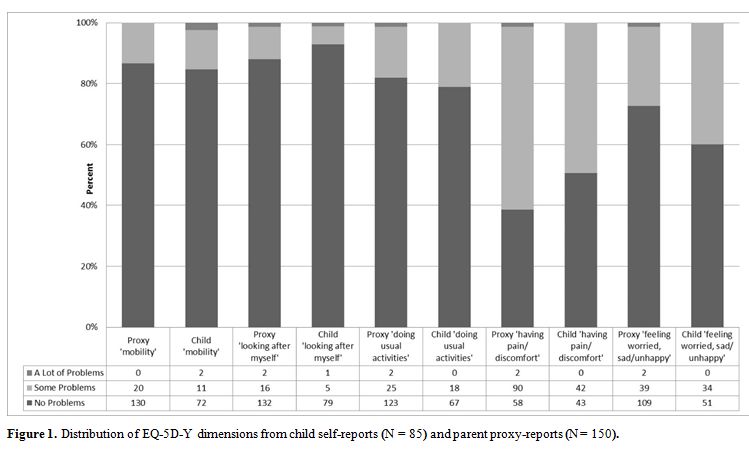

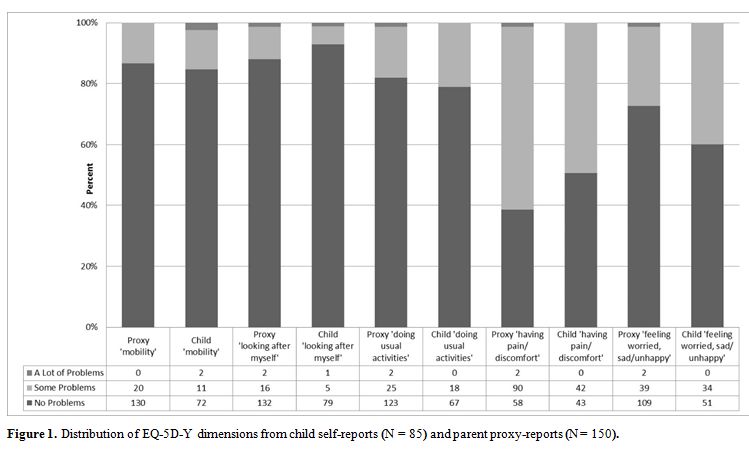

Figure 1

shows proxy and self-report EQ-5D-Y dimensions. Having some or many

problems in "suffering pain or discomfort" (49.4% child report and

61.3% parental proxy) and "feeling worried, sad or unhappy" (40% child

and 27.3% parental proxy) was reported more often than for "doing usual

activities" (21.2% child and 18% parental proxy) and "mobility" (15.3%

and 13.3%). "Looking after myself" seemed to pose the least difficulty:

7.1% and 12%. Mobility was the sole area with more problems for TDT

patients versus NTDT from parental proxy perspectives (p

= 0.004) (data not shown). Significant differences were seen in

parental proxy reports for EQ-5D-Y VAS regarding the type of payment

and serum ferritin levels. Those using any reimbursement and patients

with lower ferritin levels had higher EQ-5D-Y VAS compared to those

with self-payment or under UC coverage with higher ferritin levels (p = 0.026 and 0.031) (data not shown).

|

Figure 1. .Distribution of EQ-5D-Y dimensions from child self-reports (N = 85) and parent proxy-reports (N = 150). |

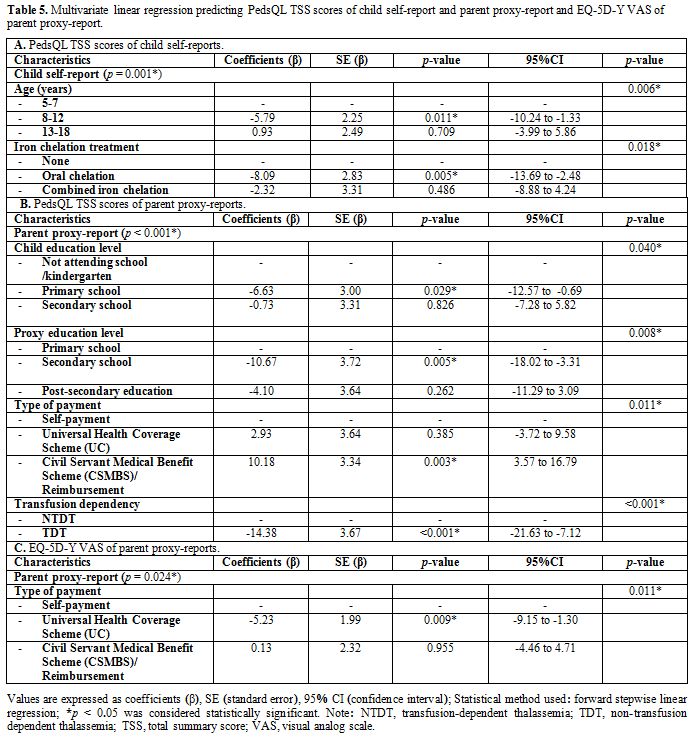

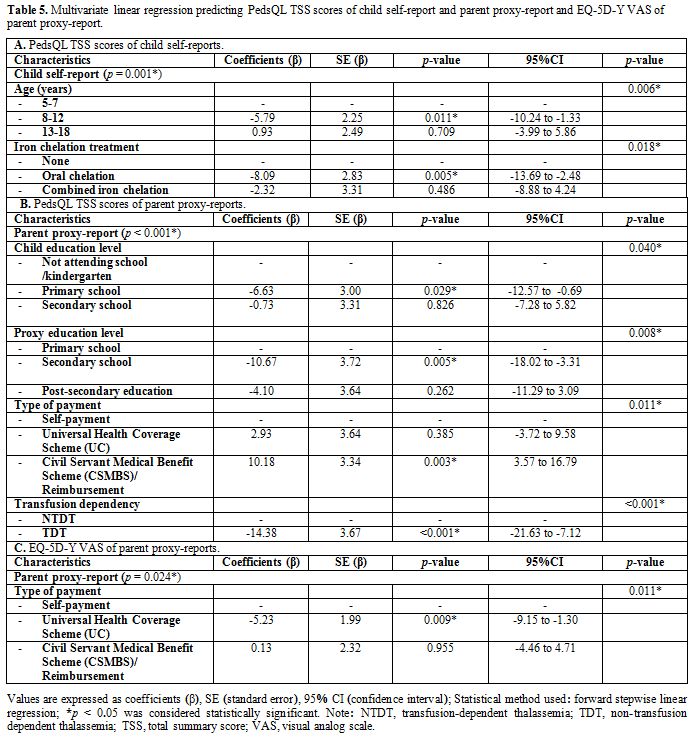

Linear regression analysis for predictors of HRQoL scores.

Using a forward stepwise linear regression method for our final model,

age group and iron chelation treatment were independently associated

with child self-report PedsQL TSS (R2 = 0.118, p = 0.001) (Table 5A). An age of 8-12 years negatively predicted PedsQL TSS versus one of 5 - 7 years (p = 0.011). Oral chelation therapy reduced PedsQL TSS significantly as compared to those having no iron chelation (p = 0.005). The same regression model examined factors affecting PedsQL TSS for parental proxy-reports: Table 5B.

This TSS was predicted by children's education, proxy education, type of payment, and TDT (R = 0.239, p

< 0.001). Primary school children appeared to experience negative

impacts, according to their parents/guardians, as opposed to those not

attending school or in kindergarten (p

= 0.029). Parent proxies with a secondary school education seemed to

have lower TSS compared to parents/guardians with less education (p =

0.005). Parental proxy reports of TDT patients displayed poorer TSS

than those children with NTDT (p < 0.001). Interestingly, there was a positive relationship between TSS and medical payment by

Civil Servant Medical Benefit Scheme (CSMBS) or any reimbursement scheme versus self-payment (p = 0.003). UC negatively predicted parental proxy EQ-5D-Y VAS in comparison with self-payment (p = 0.009) (R = 0.037, p = 0.024) (Table 5C).

|

Table 5. Multivariate

linear regression predicting PedsQL TSS scores of child self-report and

parent proxy-report and EQ-5D-Y VAS of parent proxy-report. |

Discussion

In

this single-institution study of HRQoL in Thai children with

thalassemia, we compared the unique perspectives of children and their

parent proxies from two discrete instruments: PedsQL and EQ-5D-Y.

A wealth of research using PedsQL in pediatric patients with

thalassemia[10,15-18] generally

shows it to be a reliable and valid tool for healthy and

chronically-ill children. While the EQ-5D-Y has also been used in

chronic illness, we could not find any reports of it for children with

thalassemia; our study may be the first. Two other studies have

examined children with thalassemia using different versions: EQ-5D and

EQ-5D-3L.[22,23]

EQ-5D-Y appears to have some

favorable attributes: the questionnaire is relatively quick and

straightforward for participants to complete and appropriately

comprehensible for each cognitive-developmental stage.[14,24,25]

However, we should also note that the EQ-5D-Y does not cover some

aspects of child HRQoL, such as some psychometric properties and family

relationships, which are covered by other generic instruments like

PedsQL.[26] In addition, the EQ-5D-Y can be used with

confidence in acutely-ill children but has not been as good in chronic

disorders or healthy children.[27] This study supported that EQ-5D-Y was proper to assess in chronically-ill children, like thalassemia, rapidly.

In

place of any existing research with pediatric thalassemia, we compared

our patients' EQ-5D-Y dimensions with studies on children having a

different chronic illness such as cystic fibrosis in Germany, diabetes

mellitus in Spain, and chronic kidney disease in Taiwan.[28-30]

Our thalassemia patients reported more difficulties in pain/discomfort

and anxiety/depression as compared to their usual activities, mobility,

and self-care; this mirrored the previous research. It might be assumed

that the children experience more psychosocial challenges versus

physical hindrances. Further research needs to be done using EQ-5D-Y

with pediatric thalassemia patients in other settings and certainly

over the long term.

The study demonstrated both EQ-5D-Y VAS and

dimensions had statistically significant correlations with the PedsQL

TSS, PHS, and PCHS, particularly of both child and parent proxy

reports. Parental proxy scores were also in line with the children's

from both PedsQL and EQ-5D-Y and which is consistent with our prior

research using PedsQL[16,31,32] solely. In other research,[15,16,33]

parent proxy-rated HRQoL scores were typically lower than child-rated

ones. Notably, for us, only the PHS for parent proxy-rated PedsQL was

significantly lower (p =

0.030); our TSS were slightly lower but not significantly. Regarding

this lower TSS, we can speculate parent proxies may be more concerned

about the current and future effects of their child's physical

disability, i.e., financial burdens, social interactions, etc., than

these young children are at present. However, for the significantly

lower PHS, parents/guardians may be merely relying on what they can

observe of their child's suffering. This topic could be useful to

explore in future research. Children rated their psychosocial health

lower than their physical health in the PedsQL, particularly for the

scholarly function; this also matches several past studies.[10,15-18,24]

Perhaps this is due to frequent school absences, restrictions within

social activities at school, physical pain from medical procedures such

as venipuncture, intravenous access for transfusion, or injection, or

even lower self-esteem.

We were pleasantly surprised that all of

our current parental proxy and self-reported HRQoL scores were

noticeably higher when compared to a decade-old report that was written

pre-implementation of the TIF guidelines, from our hospital.[16]

It is hoped this is a result of consistent improvements in medical care

over the last ten years, but it may also reflect a broader social

acceptance of chronic illnesses and other external changes. The

implementation of the TIF guidelines toward improving thalassemia care

management at our hospital, better subspecialty pediatric care, and

greater availability of oral iron chelation drugs may have raised HRQoL

scores. Better health care is likely to have resulted in less pain and

discomfort for patients and improved social interactions and

functions. One important point may be the ability to have

subcutaneous administration equipment at home in cases requiring

combined iron chelation. Although the procedure remains physically

uncomfortable, it may be more convenient for children and

parents/guardians to have this take place in the home.

It

must be noted that our lower ratio of TDT versus NTDT, 1/5 of the

patients in this paper as compared to 1/3 in the past, may have

resulted in higher HRQoL than previously. While it may merely be that

patients are happier because their disease is less severe, this finding

requires further examination as we had twice the number of participants

here: 150 versus the 75 before. This lower proportion of TDT may

be the longer-term outcomes of the national screening policy for severe

types of thalassemia, coupled with the better general social awareness

of thalassemia and its effects.

This study examined predictors

of HRQoL using stepwise linear regression from both PedsQL and EQ-5D-Y

VAS. For the PedsQL, age was significantly associated with HRQoL

according to children's self-report data, similar to prior reports.[10,34]

Patients 8-12 years old had lower HRQoL, leading to us to see this age

group as a negative predictor. As this age group often experiences a

transition from preschool to elementary school, they may be worried

about their learning ability or school absences. As they grow older,

children naturally become more aware of any differences from their

peers.

For our patients, iron chelation therapy, particularly

oral chelation, significantly and negatively impacted HRQoL. Leafy MS

et al.[35] observed all patients experienced burden with chelation, no matter which type. Similarly, Thavorncharoensap et al.[10]

stated that iron chelation treatment was associated with poorer

HRQOL.Three other studies found that patients using oral chelators,

especially deferasirox, had a better quality of life versus those using

injectable forms.[22,36,37]

However, we must state that these findings may differ from ours due to

the particular breakdown of our chelation patients. First of all, only

29/150 of our patients received any kind of chelation therapy (Table 4), which is relatively low. Of these 29 patients, 17 used oral chelation, and 12 used combined oral/injection.

Moreover,

most of our patients use deferiprone versus deferasirox as it is

cheaper and more accessible in Thailand. We imagine that any

patients taking oral chelation already are experiencing iron overload

and more likely to develop complications related to this; thus, they

would have a worse quality of life in relation to more severe disease.

Medications' side effects and the burden of compliance would likely be

factors to explore further.

Parental proxy-reports for PedsQL

outlined some unique and significant associations with

HRQoL: child education, proxy education, type of payment, and

transfusion dependency. Similar to the self-reports, parents/guardians

also believed that primary school children had lower HRQoL. Caregivers

may be concerned about both social integration and school performance

at this age. Furthermore, our results seemed to show that parental

proxy education at the secondary school level was significantly

correlated with lower perceived children's HRQoL; university education

was as well but not significantly. A subgroup analysis of the impact of

parental education on HRQoL (N=129: 94 mothers and 35 fathers) also

revealed a concordance in which parents with secondary school

completion had the lowest PedsQL TSS (p

= 0.037, data not shown). Our datum does not appear to concur

with an Egyptian and Iraqi paper that reported high levels of parental

education were associated with higher HRQoL outcomes.[18,32,36]

It is only speculation at this point, but perhaps caregivers who

completed secondary school in Thailand are more anxious about the

challenges their children might face, or this might merely be a

cultural difference. Thailand people with less education could be more

inclined to trust the public health care system, whereas those with

more education may be prone to have more doubt as they may have access

to alternatives. This tendency should be further explored by an

in-depth interview study.

Family economic status appeared to play

a significant role in the PedsQL measurement of HRQoL, similar to the

previous Thai study.[16] For example, CSMBS/any

reimbursement system had positive impacts on parental proxy

perspectives. Probably, the type of payment is, in itself, a proxy for

familial disposable income and access to financial assets. Besides,

CSMBS and the other reimbursement schemes offer a wider variety of

treatment choices and convenience. This is especially relevant for the

location of treatment, as people under UC are obligated to seek care in

the region where they were registered, and sometimes families work and

live elsewhere. Indeed, parental proxy reports showed that the

Use of UC negatively predicted the EQ-5D-Y VAS, in comparison with

self-payment.

Overall, all PedsQL scores, both parental and

child proxies, were lower for children who were TDT. Unsurprisingly,

parent proxies of children with TDT reported significantly lower TSS

than NTDT parent proxies, after using multivariate linear regression.

This finding is in line with prior research[10,16,18]

and is likely because of disease severity along with the inconvenience

and perceived distress during treatment, as mentioned before. However,

another Thai study[15] in teenagers with thalassemia

reported no differences in PedsQL scores between TDT and NTDT; this

latter paper had a higher amount of TDT patients. The differing scores

may be a result of attitude changes with age.

The most critical

limitation in our study is the absence of a control group of healthy

children. It would be useful to repeat this work incorporating healthy

controls with the EQ-5D-Y, to see if the results still stand, along

with the PedsQL.The EQ-5D-Y may indeed be appropriate for children with

thalassemia; however, this is unknown at this point as we have no other

research to compare it with. It certainly would be appropriate to

repeat this study in five or ten years and see if scores improve or

reduce in line with public policy and health care access. A higher

number of participants, along with data from other centers, would also

give a clearer picture of HRQoL.

Conclusions

This

is the first study attempting to use the EQ-5D-Y with Thai pediatric

thalassemia patients, comparing EQ-5D-Y and PedsQL scores from parent

proxies and children. Within our limited data, it appears the EQ-5D-Y

might be useful for measuring the quality of life in these children.

Predictors of lower HRQoL scores, according to self-report, included

the age of 8 - 12 years and oral chelation. Parental proxy-report

predictors of lower scores were primary school education for children,

secondary school parental proxy education, UC healthcare payment, and

transfusion dependency. Overall, HRQoL scores were higher from our

institution's report ten years ago; this may be due to better

management guidelines as well as a better standard of care, including

access to more specialists. Further long-term research needs to take

place, especially to improve the quality of life for TDT

patients.

Acknowledgments

The

authors wish to thank the MAPI Research Institute and the EuroQoL for

allowing the Use of the PedsQL and the EQ-5D-Y instruments. We would

also express our gratitude to all patients and their parents/guardians

for their participation, Associate Professor Dr. Wallee Satayasai and

Dr. Tasama Pusongchai for recruiting participants and their valuable

support, and Professor Dr. Paskorn Sritipsukho for his contribution to

the statistical analysis consultation. We would like to thank the

Center of Excellence in Applied Epidemiology for supporting. The

English language editing was done by Debra Kim Liwiski, international

instructor, Clinical Research Center, Faculty of Medicine, Thammasat

University. The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support

provided by Faculty of Medicine, Thammasat University, contract:

K.10/2562.

References

- Weatherall DJ, Clegg JB, eds. The Thalassaemia Syndromes. 4th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2001. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470696705

- Weatherall

DJ. The inherited diseases of hemoglobin are an emerging global health

burden. Blood. 2010;115(22):4331-6.

https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2010-01-251348 PMid:20233970

PMCid:PMC2881491

- Taher AT, Weatherall DJ, Cappellini MD. Thalassaemia. Lancet. 2018;391(10116):155-67. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31822-6

- Chaibunruang

A, Sornkayasit K, Chewasateanchai M, Sanugul P, Fucharoen G, Fucharoen

S. Prevalence of Thalassemia among Newborns: A Re-visited after 20

Years of a Prevention and Control Program in Northeast Thailand.

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2018; 10(1): e2018054. https://doi.org/10.4084/mjhid.2018.054 PMid:30210747 PMCid:PMC6131105

- Fucharoen

S, Winichagoon P. Thalassemia in Southeast Asia: problems and strategy

for prevention and control. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health.

1992;23:647-55.

- Cappellini MD, Cohen A,

Porter J, Taher A, Viprakasit V, editors. Guidelines for the management

of transfusion dependent thalassaemia (TDT). 3rd edition. Nicosia

(Cyprus): Thalassaemia International Federation; 2014.

- Taher

A, Vichinsky E, Musallam K, Cappellini MD, Viprakasit V, editors.

Guidelines for the management of non-transfusion dependent thalassaemia

(NTDT). Nicosia (Cyprus): Thalassaemia International Federation; 2013.

- Varni

JW, Limbers CA. The pediatric quality of life inventory: measuring

pediatric health-related quality of life from the perspective of

children and their parents. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56(4):843-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2009.05.016 PMid:19660631

- Matza

LS, Swensen AR, Flood EM, Secnik K, Leidy NK. Assessment of

health-related quality of life in children: a review of conceptual,

methodological, and regulatory issues. Value Health. 2004;7(1):79-92. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2004.71273.x PMid:14720133

- Thavorncharoensap

M, Torcharus K, Nuchprayoon I, Riewpaiboon A, Indaratna K, Ubol BO.

Factors affecting health-related quality of life in Thai children with

thalassemia. BMC Blood Disord. 2010;10:1-10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2326-10-1 PMid:20180983 PMCid:PMC2836992

- Pakbaz

Z, Treadwell M, Yamashita R, Quirolo K, Foote D, Quill L, Singer T,

Vichinsky EP. Quality of life in patients with thalassemia intermedia

compared to thalassemia major. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1054:457-61. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1345.059 PMid:16339697

- Varni

JW, Seid M, Kurtin PS. PedsQL 4.0: reliability and validity of the

Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory version 4.0 generic core scales in

healthy and patient populations. Med Care. 2001 Aug;39(8):800-12. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-200108000-00006 PMid:11468499

- Sritipsukho

P, Wisai M, Thavorncharoensap M. Reliability and validity of the Thai

version of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0. Qual Life Res.

2013;22(3):551-7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-012-0190-y PMid:22552603

- Wille

N, Badia X, Bonsel G, Burstrom K, Cavrini G, Devlin N, et al.

Development of the EQ-5D-Y: a child-friendly version of the EQ-5D. Qual

Life Res. 2010; 19(6): 875-886. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9648-y PMid:20405245 PMCid:PMC2892611

- Boonchooduang

N, Louthrenoo O, Choeyprasert W, Charoenkwan P. Health-related quality

of life in adolescents with thalassemia. Pediatr Hematol Oncol.

2015;32(5):341-8. https://doi.org/10.3109/08880018.2015.1033795 PMid:26086564

- Surapolchai

P, Satayasai W, Sinlapamongkolkul P, Udomsubpayakul U. Biopsychosocial

predictors of health-related quality of life in children with

thalassemia in Thammasat University Hospital. J Med Assoc Thai. 2010;93

Suppl 7:S65-75.

- Mettananda S, Pathiraja

H, Peiris R, Bandara D, Silva U, Mettananda C. Health related quality

of life among children with transfusion dependent β-thalassaemia major

and haemoglobin E β-thalassaemia in Sri Lanka: a case control study.

Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019; 17: 137. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-019-1207-9 PMid:31395066 PMCid:PMC6686351

- Adam

S, Afifi H, Thomas M, Magdy P, El-Kamah G. Quality of life outcomes in

a pediatric thalassemia population in Egypt. Hemoglobin.

2017;41(1):16-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630269.2017.1312434 PMid:28440111

- World

Health Organization. WHO Anthro for personal computers, version 3.2.2,

2011: Software for assessing growth and development of the world's

children. Geneva: WHO, 2010. Available at: https://www.who.int/childgrowth/software/en/. Accessed: January 30, 2020.

- World

Health Organization. WHO AnthroPlus for personal computers manual:

software for assessing growth of the world's children and adolescents.

Geneva: WHO; 2009. Available at: https://www.who.int/growthref/tools/en/. Accessed: January 30, 2020.

- EuroQol Group. EQ-5D-Y User Guide.: Basic information on how to use the EQ-5D-Y instrument. Available at: http://www.euroqol.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Documenten/PDF/Folders_Flyers/EQ-5D-Y_User_Guide_v1.0_2014.pdf. Accessed: May 5, 2020.

- Seyedifar

M, Dorkoosh FA, Hamidieh AA, Naderi M, Karami H, Karimi M, Fadaiyrayeny

M, Musavi M, Safaei S, Ahmadian-Attari MM, Hadjibabaie M, Cheraghali

AM, Akbari Sari A. Health-related quality of life and health utility

values in beta thalassemia major patients receiving different types of

iron chelators in Iran. Int J Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Res.

2016;10(4):224-31.

- Shaligram D, Girimaji

SC, Chaturvedi SK. Psychological problems and quality of life in

children with thalassemia. Indian J Pediatr. 2007;74(8):727-30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-007-0127-6 PMid:17785893

- Burström

K, Bartonek A, Broström EW, Sun S, Egmar C. EQ-5D-Y as a health-related

quality of life measure in children and adolescents with functional

disability in Sweden: testing feasibility and validity. Acta Paediatr.

2014;103(4):426-35. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.12557 PMid:24761459

- Kreimeier

S, Greiner W. EQ-5D-Y as a health-related quality of life instrument

for children and adolescents: The instrument's characteristics,

development, current Use, and challenges of developing its value set.

Value Health. 2019;22(1):31-37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2018.11.001 PMid:30661631

- Noyes

J, Edwards RT. EQ-5D for the assessment of health-related quality of

life and resource allocation in children: a systematic methodological

review. Value Health. 2011;14(8):1117-29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2011.07.011 PMid:22152182

- Scott

D, Ferguson GD, Jelsma J. The Use of the EQ-5D-Y health related quality

of life outcome measure in children in the Western Cape, South Africa:

psychometric properties, feasibility and usefulness - a longitudinal,

analytical study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0590-3 PMid:28103872 PMCid:PMC5248508

- Eidt-Koch

D, Mittendorf T, Greiner W. Cross-sectional validity of the EQ-5D-Y as

a generic health outcome instrument in children and adolescents with

cystic fibrosis in Germany. BMC Pediatr. 2009; 9: 55. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-9-55 PMid:19715563 PMCid:PMC2753333

- Mayoral

K, Rajmil L, Murillo M, Garin O, Pont A, Alonso J, Bel J, Perez J,

Corripio R, Carreras G, Herrero J, Mengibar JM, Rodriguez-Arjona D,

Ulrike Ravens-Sieberer U, Raat H, Serra-Sutton V, Ferre Mr. Measurement

properties of the online EuroQol-5D-Youth instrument in children and

adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus: questionnaire study. Med

Internet Res. 2019; 21(11): e14947. https://doi.org/10.2196/14947 PMid:31714252 PMCid:PMC6880238

- Hsu

CN, Lin HW, Pickard AS, Tain YL. EQ-5D-Y for the assessment of

health-related quality of life among Taiwanese youth with

mild-to-moderate chronic kidney disease. Int J Qual Health Care.

2018;30(4):298-305. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzy011 PMid:29447362

- Varni

JW, Limbers CA, Burwinkle TM. How young can children reliably and

validly self-report their health-related quality of life? An analysis

of 8,591 children across age subgroups with the PedsQL™ 4.0 Generic

Core Scales. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5: 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-5-1 PMid:17201920 PMCid:PMC1769360

- Mikael

NA, Al-Allawi NA. Factors affecting quality of life in children and

adolescents with thalassemia in Iraqi Kurdistan. Saudi Med J.

2018;39(8):799-807 https://doi.org/10.15537/smj.2018.8.23315 PMid:30106418 PMCid:PMC6194984

- Caocci

G, Efficace F, Ciotti F, Roncarolo MG, Vacca A, Piras E, Littera R,

Markous RSD, Collins GS, Ciceri F, Mandelli F, Marktel S, Nasa GL.

Health related quality of life in Middle Eastern children with

beta-thalassemia. BMC Blood Disord. 2012;12:6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2326-12-6 PMid:22726530 PMCid:PMC3496588

- Ismail

A, Campbell MJ, Ibrahim HM, Jones GL. Health related quality of life in

Malaysian children with thalassaemia. Health Qual Life Outcomes.

2006;4:39. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-4-39 PMid:16813662 PMCid:PMC1538578

- Elalfy

MS, Massoud W, Elsherif NH, Labib JH, Elalfy OM, Elaasar S, von

Mackensen S. A new tool for the assessment of satisfaction with iron

chelation therapy (ICT-Sat) for patients with β-thalassemia major.

Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58(6):910-5. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.23413 PMid:22232075

- Abdul-Zahra

HA, Hassan MK, Ahmed BA. Health-related quality of life in children and

adolescents with β-thalassemia major on different iron chelators in

Basra, Iraq. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2016;38(7):503-11. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPH.0000000000000663 PMid:27606437

- Goulas

V, Kourakli-Symeonidis A, Camoutsis C. Comparative Effects of Three

Iron Chelation Therapies on the Quality of Life of Greek Patients with

Homozygous Transfusion-Dependent Beta-Thalassemia. ISRN Hematol. 2012;

2012: 139862. https://doi.org/10.5402/2012/139862 PMid:23316378 PMCid:PMC3534333

Supplementary Table

|

Supplementary Table 1.

Correlations between PedsQL and EQ-5D-Y dimensions and VAS among child

self-reports and parent proxy-reports. |

[TOP]