Donato Rigante1,2.

1 Department of Life Sciences and Public Health, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS, Rome, Italy.

2 Università Cattolica Sacro Cuore, Rome, Italy.

Correspondence to: Donato Rigante, MD, PhD, Department of Life Sciences

and Public Health, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli

IRCCS, Università Cattolica Sacro Cuore, Rome, Largo A. Gemelli 8,

00168 Rome, Italy. Tel: +39 06 30154475. Fax +39 06 3383211. E-mail:

donato.rigante@unicatt.it

Published: July 1, 2020

Received: May 21, 2020

Accepted: June 17, 2020

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2020, 12(1): e2020039 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2020.039

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Although

the etiology of Kawasaki disease (KD) remains elusive, the available

evidence indicates that the primum movens may be a dysregulated immune

response to various microbial agents, leading to cytokine cascade and

endothelial cell activation in patients with KD. Documented infections

by different viruses in many individual cases have been largely

reported and are discussed herein, but attempts to demonstrate their

causative role in the distinctive KD scenario and KD epidemiological

features have been disappointing. To date, no definite link has been

irrefutably found between a single infection and KD.

|

The History of Kawasaki Disease

Almost

60 years ago, dr. Tomisaku Kawasaki noted, for the first time, a

strange association of symptoms in a 4-year-old boy who was

hospitalized at the Chiba University. The child had prolonged high

fever, conjunctivitis, a widespread rash all over the body, and a

bright-red tongue. However, he could not explain that disease, thinking

to an allergy or any infectious diseases. Antibiotics were ineffective

in treating that boy's symptoms, which subsided only after two weeks,

also revealing specific desquamation of the fingers and toes. One year

later, another child was hospitalized with those same symptoms, and dr.

Kawasaki convinced himself that a mysterious illness could affect

children. In 1967 he published a 44-page report of all hospitalized

patients having that illness (that he named "acute febrile

mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome") in the Japanese journal "Arerugi",

usually dedicated to allergology, which was based on a diligent 6-year

observation of 50 patients.[1] The eponym of Kawasaki

disease (KD) was coined later, when an international journal offered a

large amount of space to the description of this illness.[2]

With some cases of sudden death occurring after an apparent resolution

of KD, the issue started to gain more and more attention by the

scientific community, and pediatric textbooks started to report on this

condition.

A Systemic Vasculitis is the Key to Explain Kawasaki Disease

In

plain terms, KD is a systemic vasculitis that mainly and typically

occurs in infants and children less than five years: the most ominous

complication of patients with KD is the occurrence of coronary artery

abnormalities (CAA).[3] For this reason, KD is actually the leading cause of acquired pediatric heart disease in the developed world.[4]

Many reports found that coronary arteritis occurred at the highest

incidence, but that vasculitis developed at various sites throughout

the body. Vascular lesions of KD may start in the tunica interna and

externa of medium-sized muscular arteries, such as the coronary

arteries, but also in arterioles, venules and capillaries, while

inflammation disseminates to large arteries including the coronary

arteries.[5,6] The media of affected vessels

demonstrates edematous dissociation of the smooth muscle cells, while

endothelial cell swelling and subendothelial edema are seen. An influx

of neutrophils can be observed in the early stages of KD, with a rapid

transition to large mononuclear cells in concert with lymphocytes and

IgA plasma cells. Destruction of the internal elastic lamina and an

eventual fibroblast proliferation can occur later. This active

inflammation is replaced over several weeks to months by progressive

fibrosis, with scar formation and remodeling.[7]

The Clinical Chameleon of Kawasaki Disease

The

classic diagnosis of KD has been historically based on the presence of

5 days of fever and a typical constellation of nonspecific clinical

signs described in 1967 by dr. Kawasaki: upholding the diagnosis of KD

requires that highly swinging fever is combined with at least 4 out of

5 "main" clinical features: [a] bilateral non-exudative conjunctivitis,

[b] unilateral cervical lymphadenopathy, [c] polymorphous rash, [d]

changes in the extremities (mainly in the form of angioedema) or in the

perineal region (an early-onset desquamating rash) and [e] changes in

the lips and/or oral cavity (dry fissured or reddened lips with a

strawberry-like tongue).[8] Although the clinical

clues of KD are easily recognizable, its underlying mechanisms are

under deep investigation and remain poorly understood. Treatment of KD

requires intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and aspirin during the first

ten days of illness, and its ultimate goal is avoiding the occurrence

of CAA.[9] Mostly in the case of resistance to IVIG,

inflammatory cells reach the vasa vasorum of coronary arteries with the

risk of fragmentation of the internal lamina and damage to the media,

resulting in the formation of CAA.[10] Higher values

of C-reactive protein and younger age at onset are crucial points in

determining respectively a failure in response to IVIG and a higher

risk that the disease could be complicated by CAA.[11]

Early ascertainment of non-responders to IVIG who might require

additional therapies reducing the development of CAA is still a

challenge.[12] With improved treatment methods and

different drugs useful for refractory cases, the mortality rate of KD

has dropped dramatically in recent years. However, despite increased

awareness, the number of patients with KD presenting with incomplete or

atypical features is increasing across the world. Incomplete cases of

KD are characterized by less than four main clinical signs and atypical

ones by a broad range of unusual clinical features, including aseptic

meningitis, peripheral facial nerve palsy, liver impairment with

jaundice, gallbladder hydrops, pneumonia-like disease, and even

macrophage activation syndrome.[13,14]

Different Potential Causes, One Resulting Disease

Despite

extensive research, the etiology of KD is far to be unraveled, and no

single pathognomonic clinical or laboratory finding for diagnosis has

been identified. Indeed, the occurrence of KD in epidemics, as shown by

nationwide epidemiologic surveys conducted with biennial frequency

since 1970, reveals a potential relationship of KD with an infectious

disease. A number of infectious agents, both bacterial and viral, have

been isolated from patients with KD through the years,[15] but also non-infectious triggers are presumed to cause the disease.[16]

Further KD characteristics such as high-grade fever, elevated

acute-phase reactants, and elevated white blood cell count strongly

suggest an infectious cause, and in particular, some characteristics

may suggest a viral etiology, such as the self-limited course of KD,

skin rash and conjunctivitis. A host of reports have clarified the

distinct seasonality of KD in geographically distinct regions of the

northern hemisphere, revealing that various triggers may be operating

at different times of the year in various geospatial clustering of KD

cases:[17] the seasonality of KD, with winter peaks

in Japan and winter-spring predominance in the USA or in many other

temperate areas, is highly suggestive of a viral etiology.[18]

Shimizu et al. found a seasonal effect also on the response to IVIG

treatment, with more patients manifesting resistance to IVIG in the

warm seasons from May to October, but no differences in the general

outcome of CAA.[19] Several epidemiological studies

have also demonstrated that KD is frequently associated with a previous

respiratory illness; however, no differences have been found in

children stratified according to positive or negative respiratory viral

testing; in fact, a positive test for respiratory viruses at the time

of presentation should not be used to exclude the diagnosis of KD.[20]

A Viral Infection to Switch on Kawasaki Disease

Searching

for papers dedicated to KD and published in the last 35 years through

PubMed (matching the terms "KD" and "virus" or "viral infection"), a

list of viral agents hypothetically associated with KD can be drawn

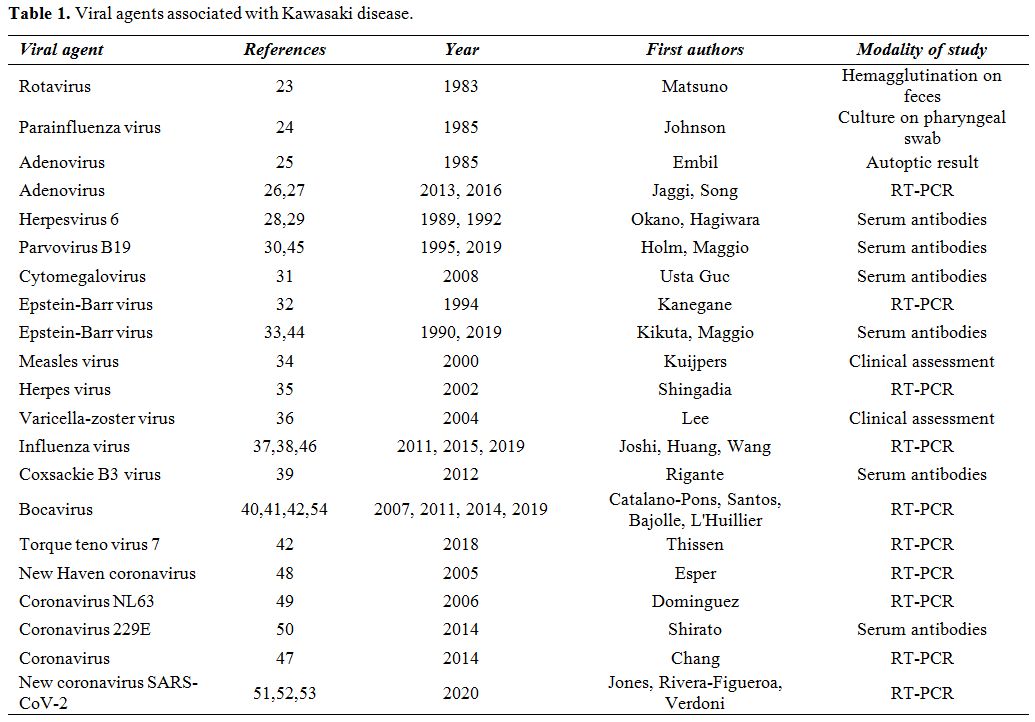

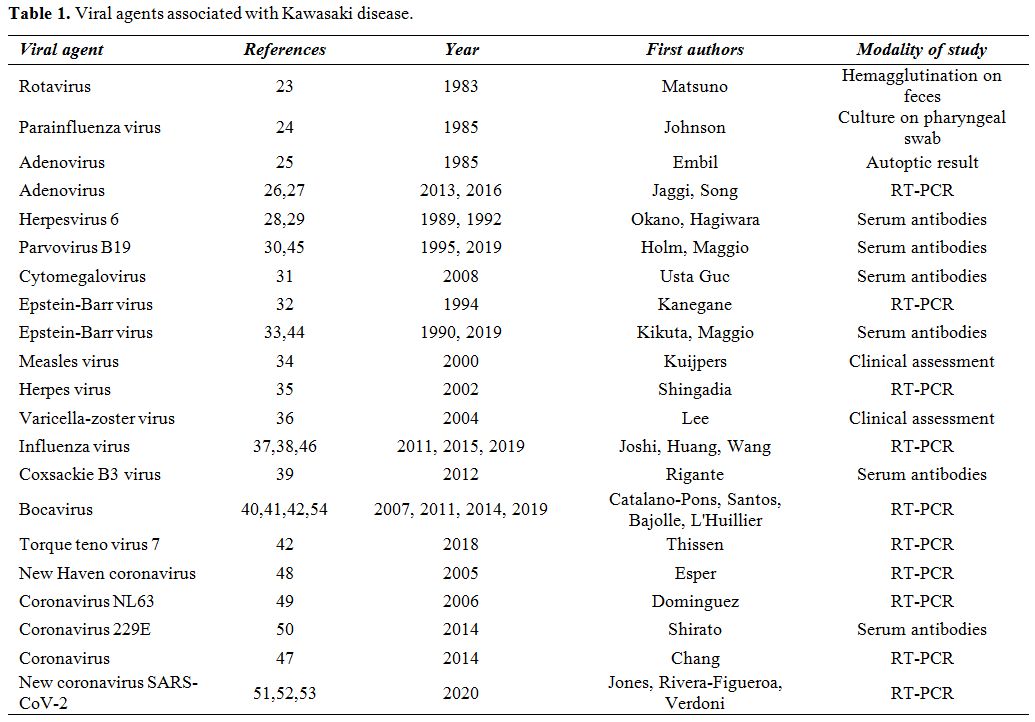

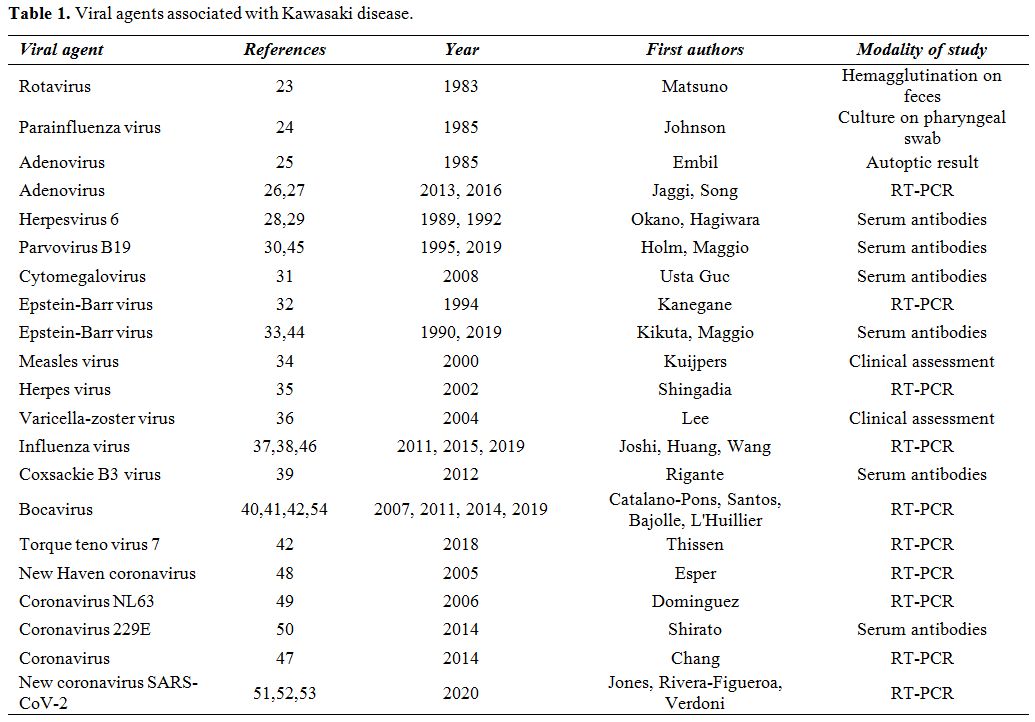

(see Table 1). Viral respiratory infections have been commonly found at the diagnosis of KD,[21] but they do not seem to affect patients' response to IVIG or influence the overall outcome.[22] The oldest reports date back to 1983 when rotavirus was found in the feces of children with KD[23] and to 1985 when parainfluenza virus and adenovirus were encountered.[24,25] A molecular-based adenovirus detection is relatively frequent in KD patients but should be interpreted with caution.[26]

Indeed, 24 out of 25 children with adenovirus disease mimicking

features of KD had a higher viral burden compared to those with KD and

incidental adenovirus detection.[27] Anecdotal reports had been associated KD to human herpesvirus-6, parvovirus B19 and cytomegalovirus.[28-31] However, the highest number of KD reports has been related to Epstein-Barr virus,[32,33] while KD cases with a concomitant infection caused by measles virus,[34] herpesvirus,[35] varicella-zoster virus,[36] influenza virus,[37,38] coxsackie virus,[39] and bocavirus are mostly isolated reports.[40]

In particular for bocavirus, its nucleic acid was found in the

nasopharyngeal, serum and stool samples from 5/16 (31.2%) patients with

KD by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR).[41]

A prospective study by Bajolle et al. revealed that bocavirus was

present in the serum of 3/32 (9%) and in the nasopharyngeal aspirate of

7/32 (21.8%) patients with KD, who probably had a previous bocavirus

infection heralding KD.[42] Metagenomic sequencing

and PCR detected torque teno virus 7 in only 2/11 (18%) patients with

KD prospectively evaluated for one year,[43] while the most recent reports have highlighted the association of KD with Epstein-Barr virus,[44] parvovirus B19[45] and influenza virus.[46]

|

Table 1. Viral agents associated with Kawasaki disease. |

The Outbreak of the New Coronavirus and Kawasaki Disease

The

latest outbreak of the new coronavirus (HCoV) infection (named

SARS-CoV-2) and the resulting pandemic threat to health worldwide has

required strict social containment measures since February 2020, but

has also spread the suspicion that this peculiar infection might

trigger KD. As a matter of fact, HCoV has been associated with many

reports of KD in the past: for instance, in a prospective

case-controlled study among Taiwanese children it was isolated in 7.1%

of cases.[47] In 2005 Esper et al. identified a novel

human HCoV, named "New Haven," in the respiratory secretions from 8/11

children with KD.[48] However, in Denver (Colorado,

USA) the prevalence of HCoV-NL63 infection was not higher in KD

patients compared with non-KD controls.[49] The

contribution of HCoV-229E infection in the development of KD was also

brought in question by Shirato et al., who used immunofluorescence

testing to detect virus-neutralizing antibodies in 15 patients with KD

before IVIG treatment.[50] The first case of KD

associated with a concomitant SARS-CoV-2 infection was a 6-month infant

hospitalized in Palo Alto (California, USA). However, the clinical

significance of patient's positive testing remained unclear in the

setting of KD.[51] Furthermore, a 5-year-old

Afro-American boy was found to have KD-related signs in Jackson

(Mississippi, USA) in combination with severe acute respiratory

distress and shock syndrome, referred to SARS-CoV-2 infection detected

via RT-PCR from his nasopharyngeal swab.[52] In April

2020, Verdoni et al. reported a 30-fold increased incidence of KD-like

syndrome in children living in the Bergamo province of Italy, after the

SARS-CoV-2 epidemic began in that same area, also showing higher rates

of heart involvement and general features of macrophage activation or

shock syndrome. The evidence of contact with the virus was confirmed by

the presence of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 in 8 out of 10 reported

patients.[53] This study had the limitation of being

based on a small case series, but suggested in-depth genetic analysis

to investigate the potential susceptibility to KD after a triggering

effect of SARS-CoV-2.

The Evidence about Viral Contributors to Kawasaki Disease

Ultimately,

viruses may be confounding bystanders in many descriptions of KD.

However, intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies sharing morphologic features

among several different RNA viral families have been found in autoptic

tissues of patients deceased for KD.[54] Rowley et

al. speculated that the development of KD could follow ubiquitous RNA

viruses causing an asymptomatic infection or a very mild disease in the

vast majority of children, but specifically "KD" in a subset of

genetically selected people.[55] In addition, a pilot

study investigating KD pathogenesis revealed specific viral signatures

in 4/7 patients with KD via high-throughput sequencing on blood

specimens, although 2 were corresponding to their vaccinal history

(oral poliovirus and measles/mumps/rubella vaccine) and 2 to bocavirus

and rhinovirus, which could suggest a temporal association with the

disease.[56] Different studies have also found that

an imbalance in the gut microbiota might interfere with the normal

function of innate and adaptive immunity, and that variable microbiota

interactions with environmental factors, mainly infectious agents,

might drive the development of KD in a genetically susceptible child.[57] However, to date, no definite link has been irrefutably found between any viral agents and KD.

Conclusive Remarks

More

than half a century after its discovery, it is frustrating to admit

that KD is believed to be triggered by an infection, but that its

direct unequivocal cause is unclear. Besides, at the age of 95, dr.

Kawasaki remains very active and continues to support families with KD

children through different nonprofit organizations. New theories about

KD hypothesize that the disorder might be conceived as an

autoinflammatory condition,[58] in which inflammation

explodes without any involvement of autoimmune pathways and any sound

relationship with microbial agents.[59-61] Although

KD causal factors are still elusive, the available evidence indicates

that the primum movens may be a dysregulation of immune responses to

various infectious agents, i.e., a kind of immune-mediated "echo"

induced also by a viral infection. Even if several data might suggest

that KD is an infection-related clinical syndrome, which can develop

only in children with a predisposing genetic background, our knowledge

on both the infectious agents involved and genetic characteristics of

susceptible children remains poor. Understanding the molecular players

responsible for dysregulation of the immune response in KD will foster

the development of improved predictive tools and a more rational use of

therapeutic agents to decrease the risk of CAA in all children with KD.

In Memoriam

On

June 5, 2020 dr. Tomisaku Kawasaki passed away at the age of 95: the

news had a profound impact on many clinicians who dedicated their

professional lives studying Kawasaki disease. He was a true model to

all pediatricians, not only with regard to his clinical acumen but

especially concerning his vibrant humanity. This article is sincerely

dedicated to the memory of Tomisaku Kawasaki.

References

- Kawasaki T. Acute febrile mucocutaneous syndrome

with lymphoid involvement with specific desquamation of the fingers and

toes in children. Arerugi 1967; 16:178-222. PMid: 6062087

- Kawasaki

T, Kosaki F, Okawa S, et al. A new infantile acute febrile

mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome (MLNS) prevailing in Japan.

Pediatrics 1974;54:271-6. PMid: 4153258

- Newburger

JW, Takahashi M, Gerber MA, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term

management of Kawasaki disease: a statement for health professionals

from the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki

Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, American Heart

Association. Pediatrics 2004;114:1708-33. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-2182 PMid:15574639

- Falcini

F, Capannini S, Rigante D. Kawasaki syndrome: an intriguing disease

with numerous unsolved dilemmas. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2011;9:17 https://doi.org/10.1186/1546-0096-9-17 PMid:21774801 PMCid:PMC3163180

- Amano

S, Hazama F, Kubagawa H, et al. General pathology of Kawasaki disease

on the morphological alterations corresponding to the clinical

manifestations. Acta Pathol Jpn 1980;30:681-94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1827.1980.tb00966.x PMid: 7446109

- Hamashima Y. Kawasaki disease. Heart Vessels Suppl 1985;1:271-6. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02072407 PMid:3843587

- Suzuki

A, Miyagawa-Tomita S, Komatsu K, et al. Active remodeling of the

coronary arterial lesions in the late phase of Kawasaki disease:

immunohistochemical study. Circulation 2000;101:2935-41. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.101.25.2935 PMid:10869266

- De

Rosa G, Pardeo M, Rigante D. Current recommendations for the

pharmacologic therapy in Kawasaki syndrome and management of its

cardiovascular complications. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2007;11:301-8.

PMid: 18074939

- Marchesi A, Tarissi De

Jacobis I, Rigante D, et al. Kawasaki disease: guidelines of the

Italian Society of Pediatrics, part I - definition, epidemiology,

etiopathogenesis, clinical expression and management of the acute

phase. Ital J Pediatr 2018;44(1):102. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-018-0536-3 PMid:30157897 PMCid:PMC6116535

- Marchesi

A, Tarissi De Jacobis I, Rigante D, et al. Kawasaki disease: guidelines

of Italian Society of Pediatrics, part II - treatment of resistant

forms and cardiovascular complications, follow-up, lifestyle and

prevention of cardiovascular risks. Ital J Pediatr 2018;44(1):103. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-018-0529-2 PMid:30157893 PMCid:PMC6116479

- Rigante

D, Valentini P, Rizzo D, et al. Responsiveness to intravenous

immunoglobulins and occurrence of coronary artery abnormalities in a

single-center cohort of Italian patients with Kawasaki syndrome.

Rheumatol Int 2010;30:841-6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-009-1337-1 PMid:20049445

- Rigante

D, Andreozzi L, Fastiggi M, et al. Critical overview of the risk

scoring systems to predict non-responsiveness to intravenous

immunoglobulin in Kawasaki syndrome. Int J Mol Sci 2016;17:278. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17030278 PMid:26927060 PMCid:PMC4813142

- Falcini

F, Ozen S, Magni-Manzoni S, et al. Discrimination between incomplete

and atypical Kawasaki syndrome versus other febrile diseases in

childhood: results from an international registry-based study. Clin Exp

Rheumatol 2012;30:799-804.

- Stabile A,

Bertoni B, Ansuini V, et al. The clinical spectrum and treatment

options of macrophage activation syndrome in the pediatric age. Eur Rev

Med Pharmacol Sci 2006;10:53-9.

- Principi N, Rigante D, Esposito S. The role of infection in Kawasaki syndrome. J Infect 2013;67:1-10 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2013.04.004 PMid:23603251 PMCid:PMC7132405

- Rigante

D, Tarantino G, Valentini P. Non-infectious makers of Kawasaki

syndrome: tangible or elusive triggers? Immunol Res 2016;64:51-4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12026-015-8679-4 PMid:26232895

- Rowley AH, Shulman ST. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of Kawasaki disease. Front Pediatr. 2018;6:374. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2018.00374 PMid:30619784 PMCid:PMC6298241

- Burns JC, Herzog L, Fabri O, et al. Seasonality of Kawasaki disease: a global perspective. PLoS One 2013;8(9):e74529. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0074529 PMid:24058585 PMCid:PMC3776809

- Shimizu D, Hoshina T, Kawamura M, et al. Seasonality in clinical courses of Kawasaki disease. Arch Dis Child 2019;104:694-6. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2018-315267 PMid:30413486

- Turnier JL, Anderson MS, Heizer HR, et al. Concurrent respiratory viruses and Kawasaki disease. Pediatrics. 2015;136:e609-14. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-0950 PMid:26304824

- Jordan-Villegas

A, Chang ML, Ramilo O, et al. Concomitant respiratory viral infections

in children with Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2010;29:770-2. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0b013e3181dba70b PMid:20354462 PMCid:PMC2927322

- Benseler

SM, McCrindle BW, Silverman ED, et al. Infections and Kawasaki disease:

implications for coronary artery outcome. Pediatrics 2005;116:e760-6. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-0559 PMid:16322132

- Matsuno S, Utagawa E, Sugiura A. Association of rotavirus infection with Kawasaki syndrome. J Infect Dis 1983;148:177. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/148.1.177 PMid:6309994

- Johnson

D, Azimi P. Kawasaki disease associated with Klebsiella pneumoniae

bacteremia and parainfluenza type 3 virus infection. Pediatr Infect Dis

J 1985;4:100-3. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006454-198501000-00024 PMid:2982131

- Embil

JA, McFarlane ES, Murphy DM, et al. Adenovirus type 2 isolated from a

patient with fatal Kawasaki disease. Can Med Assoc J 1985;132:1400.

PMid: 4005729

- Jaggi P, Kajon AE, Mejias

A, et al. Human adenovirus infection in Kawasaki disease: a confounding

bystander? Clin Infect Dis 2013;56:58-64. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cis807 PMid:23011145 PMCid:PMC3732045

- Song

E, Kajon AE, Wang H, et al. Clinical and virologic characteristics may

aid distinction of acute adenovirus disease from Kawasaki disease with

incidental adenovirus detection. J Pediatr 2016;170:325-30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.11.021 PMid:26707621

- Okano M, Luka J, Thiele GM, et al. Human herpesvirus 6 infection and Kawasaki disease. J Clin Microbiol 1989;27:2379-80. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.27.10.2379-2380.1989 PMid:2555393 PMCid:PMC267029

- Hagiwara

K, Komura H, Kishi F, Kaji T, Yoshida T. Isolation of human

herpesvirus-6 from an infant with Kawasaki disease. Eur J Pediatr

1992;151:867-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01957946 PMid:1334835

- Holm JM, Hansen LK, Oxhøj H. Kawasaki disease associated with parvovirus B19 infection. Eur J Pediatr 1995;154:633-4. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02079066 PMid:7588963

- Usta

Guc B, Cengiz N, Yildirim SV, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection in a

patient with atypical Kawasaki disease. Rheumatol Int 2008;28:387-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-007-0440-4 PMid:17717671 PMCid:PMC7079931

- Kanegane

H, Tsuji T, Seki H, et al. Kawasaki disease with a concomitant primary

Epstein-Barr virus infection. Acta Paediatr Jpn 1994;36 713-6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-200X.1994.tb03277.x PMid:7871990

- Kikuta

H, Matsumoto S, Yanase Y, et al. Recurrence of Kawasaki disease and

Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Infect Dis 1990;162:1215. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/162.5.1215 PMid:2172398

- Kuijpers

TW, Herweijer TJ, Scholvinck L, et al. Kawasaki disease associated with

measles virus infection in a monozygotic twin. Pediatr Infect Dis J

2000;19:350-3. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006454-200004000-00018 PMid:10783028

- Shingadia D, Bose A, Booy R. Could a herpesvirus be the cause of Kawasaki disease? Lancet Infect Dis 2002;2:310-3. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(02)00265-7

- Lee DH, Huang HP. Kawasaki disease associated with chickenpox: report of two sibling cases. Acta Paediatr Taiwan 2004;45:94-6.

- Joshi AV, Jones KD, Buckley AM, et al. Kawasaki disease coincident with influenza A H1N1/09 infection. Pediatr Int 2011;53:e1-2 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-200X.2010.03280.x PMid:21342333 PMCid:PMC7167673

- Huang X, Huang P, Zhang L, et al. Influenza infection and Kawasaki disease. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2015;48:243-8. https://doi.org/10.1590/0037-8682-0091-2015 PMid:26108000

- Rigante

D, Cantarini L, Piastra M, et al. Kawasaki syndrome and concurrent

Coxsackie-virus B3 infection. Rheumatol Int 2012;32:4037-40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-010-1613-0 PMid:21052673 PMCid:PMC7080020

- Catalano-Pons

C, Giraud C, Rozenberg F, et al. Detection of human bocavirus in

children with Kawasaki disease. Clin Microbiol Infect 2007;13:1220-2. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01827.x PMid:17850342

- Santos RA, Nogueira CS, Granja S, et al. Kawasaki disease and human bocavirus-potential association? https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmii.2011.01.016 PMid: 21524620

- Bajolle

F, Meritet JF, Rozenberg F, et al. Markers of a recent bocavirus

infection in children with Kawasaki disease: "a year prospective

study". Pathol Biol (Paris) 2014;62:365-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patbio.2014.06.002 PMid:25193448

- Thissen

JB, Isshiki M, Jaing C, et al. A novel variant of torque teno virus 7

identified in patients with Kawasaki disease. PLoS One

2018;13(12):e0209683. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0209683 PMid:30592753 PMCid:PMC6310298

- Maggio

MC, Fabiano C, Corsello G. Kawasaki disease triggered by EBV virus in a

child with familial Mediterranean fever. Ital J Pediatr 2019;45:129. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-019-0717-8 PMid:31627741 PMCid:PMC6798734

- Maggio

MC, Cimaz R, Alaimo A, et al. Kawasaki disease triggered by parvovirus

infection: an atypical case report of two siblings. J Med Case Rep

2019;13:104. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-019-2028-5 PMid:31014402 PMCid:PMC6480815

- Wang

J, Sun F, Deng HL, et al. Influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 virus infection in a

patient with incomplete Kawasaki disease: A case report. Medicine

(Baltimore) 2019;98(15):e15009. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000015009 PMid:30985646 PMCid:PMC6485757

- Chang LY, Lu CY, Shao PL, et al. Viral infections associated with Kawasaki disease. J Formos Med Assoc 2014;113:148-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfma.2013.12.008 PMid:24495555 PMCid:PMC7125523

- Esper

F, Shapiro ED, Weibel C, et al. Association between a novel human

coronavirus and Kawasaki disease. J Infect Dis 2005;191:499-502. https://doi.org/10.1086/428291 PMid:15655771 PMCid:PMC7199489

- Dominguez

SR, Anderson MS, Glodé MP, et al. Blinded case-control study of the

relationship between human coronavirus NL63 and Kawasaki syndrome. J

Infect Dis 2006 ;194:1697-01. https://doi.org/10.1086/509509 PMid:17109341 PMCid:PMC7199878

- Shirato

K, Imada Y, Kawase M, et al. Possible involvement of infection with

human coronavirus 229E, but not NL63, in Kawasaki disease. J Med Virol

2014;86:2146-53. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.23950 PMid:24760654 PMCid:PMC7166330

- Jones

VG, Mills M, Suarez D, et al. COVID-19 and Kawasaki disease: novel

virus and novel case. Hosp Pediatr 2020 Apr 7. pii: hpeds.2020-0123.

- Rivera-Figueroa

EI, Santos R, Simpson S, et al. Incomplete Kawasaki Disease in a child

with Covid-19. Indian Pediatr 2020 May 9:S097475591600179. PMid:

32393680

- Verdoni L, Mazza A, Gervasoni

A, et al. An outbreak of severe Kawasaki-like disease at the Italian

epicentre of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic: an observational cohort study

Lancet 2020 May 13. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31103-X

- Rowley

AH, Baker SC, Shulman ST, et al. RNA-containing cytoplasmic inclusion

bodies in ciliated bronchial epithelium months to years after acute

Kawasaki disease. PLoS One 2008;3:e1582. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0001582 PMid:18270572 PMCid:PMC2216059

- Rowley

AH, Baker SC, Shulman ST, et al. Ultrastructural, immunofluorescence,

and RNA evidence support the hypothesis of a "new" virus associated

with Kawasaki disease. J Infect Dis 2011;203:1021-30. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiq136 PMid:21402552 PMCid:PMC3068030

- L'Huillier

AG, Brito F, Wagner N, et al. Identification of viral signatures using

high-throughput sequencing on blood of patients with Kawasaki disease.

Front Pediatr 2019;7:524. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2019.00524 PMid:31921732 PMCid:PMC6930886

- Esposito

S, Polinori I, Rigante D. The gut microbiota-host partnership as a

potential driver of Kawasaki syndrome. Front Pediatr 2019;7:124. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2019.00124 PMid:31024869 PMCid:PMC6460951

- Marrani

E, Burns JC, Cimaz R. How should we classify Kawasaki disease? Front

Immunol 2018;9:2974. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02974. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.02974 PMid:30619331 PMCid:PMC6302019

- Rigante

D. A systematic approach to autoinflammatory syndromes: a spelling

booklet for the beginner. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2017;13:571-97. https://doi.org/10.1080/1744666X.2017.1280396 PMid:28064547

- Rigante

D. The broad-ranging panorama of systemic autoinflammatory disorders

with specific focus on acute painful symptoms and hematologic

manifestations in children. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2018; 10(1):

e2018067 https://doi.org/10.4084/mjhid.2018.067 PMid:30416699 PMCid:PMC6223578

- Rigante

D, Frediani B, Galeazzi M, et al. From the Mediterranean to the sea of

Japan: the transcontinental odyssey of autoinflammatory diseases.

Biomed Res Int 2013;2013:485103 https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/485103 PMid:23971037 PMCid:PMC3736491

TOP]