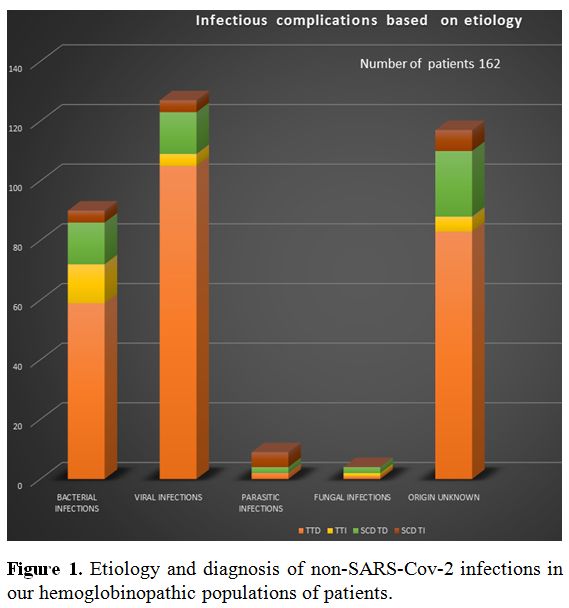

We report here a case of SARS-CoV-2 infection in a thalassemic patient and the effects of the local outbreak in hemoglobinopathic patients which have a higher incidence of infections due to abnormalities both of innate and adaptive immunity.[7] Immune abnormalities include: T lymphocytes dysfunction, decreased CD4/CD8 ratio and defects in chemotaxis and phagocytosis. Further, most of those patients have been splenectomized, with an increased incidence of bacterial/fungal infections and propensity for severity.[8] To confirm this, a longitudinal infection screening in our Center from 1996 to 2019 in 162 patients (127 with Thalassemia and 35 with SCS) reported 347 infectious events in an average time of 164 months (10-774). Seven were life-threatening, with 90 requiring hospitalization.

Events were divided by etiology and diagnosis (Figure 1) and included 114 T-TD (Thalassemia-Transfusion-Dependent), 13 T-TI (Transfusion Independent), 24 SCD-TD and 11 SCD-TI. The seven patients deceased presented sepsis in one, pneumonia with respiratory-failure in 3, HCV-related hepatocellular carcinoma in 3. One patient, aged 46, died of “overwhelming post-splenectomy sepsis syndrome” characterized by mild, flu-like symptoms followed by rapid deterioration and septic shock.

|

Figure 1. Etiology and diagnosis of non-SARS-Cov-2 infections in our hemoglobinopathic populations of patients. |

Due to these premises, hemoglobinopathies have been included in the high risk group for severe SARS-CoV-2 disease.[9]

On March 13, an endemic SARS-CoV-2 outbreak was detected in our unit. Two nurses and a secretary each presented clinically with high fever, cough, and breathing difficulties. Positive results from nasal and oral swabs confirmed that all three were infected. These three staff, all of whom were immunocompetent, had severe, long-lasting clinical manifestations of the infection and took a median of 37 (21->54) days to test negative for the virus using the swab above tests.

On the same hospital floor, 21/43 healthcare providers (HCP) in an adjacent unit tested positive with symptoms. By fearing the spread among our immunocompromised, high risk patients, the hospital direction performed immediate epidemiological surveillance. Of the 105 patients who were in contact with the infected staff, only 7 reported symptoms, all mild, in the two months surveillance, and only 1 of the 7 tested positive on the swab.

The SARS-CoV-2 positive patient, a female aged 59 with Beta-Thalassemia Major(TM)(IVS-6/745) received a transfusion on March 5, and after being notified, called the hospital on March 21 reporting mild temperature (37oC). The results of the swab, taken on March 23, was positive. The patient, after 7 days without symptoms or fever, and not having received any therapy, had a second swab negative for the virus, confirmed shortly after by a third swab.

So, our case of SARS-CoV-2 infection in TM patient was revealed during an endemic outbreak, which involved 24 symptomatic HCPs out of a staff of 52. Staff infections produced mild to severe symptoms and required therapy in most of them (antipyretic, aerosol and mucolytic therapy, antibiotics, and oxygen). Most HCPs were swab negative after 14-20 days, but 2 were still positive after >50 days.

Could we hypothesize a protective mechanism of BCH modified?

From an epidemiologic point of view, hemoglobinopathies constitute the most prevalent recessive monogenic disorders worldwide. Thalassemia has a high incidence in a broad area extending from the Mediterranean basin to parts of Africa and Asia.

The carrier frequencies for Beta-thalassemia trait (BT) in these areas range from 1 to 20%.[10] Globally; it is estimated that there are 270 million carriers with abnormal hemoglobins and thalassemias, of which 80 million are carriers of BT. A very high percentage of BT is reported in people originating from the area of the Po River’s delta (Upper Adriatic) in Italy with a high prevalence around Ferrara/Ravenna (14%), two of the northern province heavily hitten by the outbreak.[11]

SCD is the most common inherited hemoglobinopathy in the world, with the prevalence of 1-5/10.000, and >70% in sub-Saharan countries (Sudan, Chad, Nigeria, Burkina Faso, Mali and Mauritania).[12]

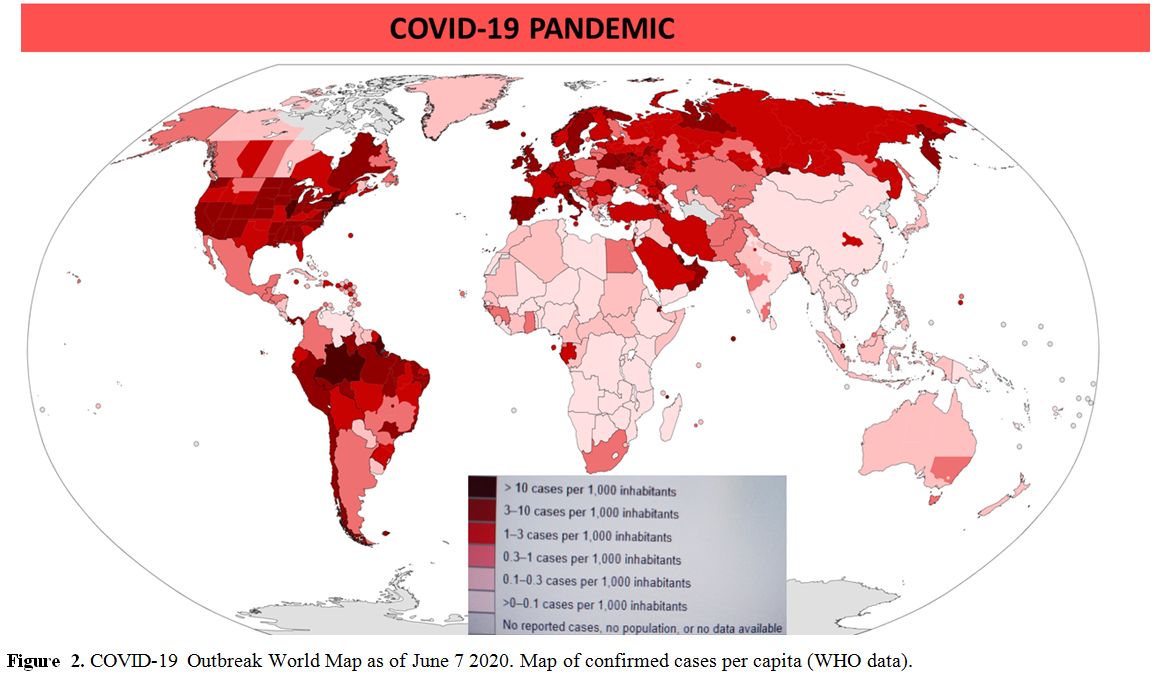

Among the world pandemic, the African continent is one of the least affected, as well as the province of Ferrara/Ravenna in Italy.

Indeed, the numbers of epidemic show a casualty rate of 37.3/100.000 inhabitants in Europe (with highest peaks in Belgium 77.9; Spain 58.4, Italy 51.9, and lowest in Germany, 4).[13]

Among northern Italian provinces, Ferrara and Ravenna stand out for a very low rate of 17/100.000 casualties compared to provinces around (Bologna 37, Modena 48, Mantova 114).[14]

The situation in Africa depends on more variables, but referring to the World Health Organization's situation reports for most recent reported case information (as of June, 7) northern countries (Algeria, Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia) and South Africa have a higher incidence (0.3–1 case per 1,000 inhabitants), while sub-Saharan countries show 0–0.1 cases per 1,000 inhabitants (Figure 2).

|

Figure 2. COVID-19 Outbreak World Map as of June 7 2020. Map of confirmed cases per capita (WHO data). |

Our hypothesis is based on results obtained in silico, but very little clinical reports of infected patients exist.

Recently a multicentric Iranian experience of 18350 Beta-thalassemic patients (only fifteen confirmed cases) reported mild to moderate disease of COVID-19.[15]

The role of ORF viral proteins, essential both in viral replication and inflammation, and the interaction with the BCH and porphyrins might be one of the links to the epidemiologic distribution and mortality among hemoglobinopathic patients? An interesting hypothesis that only further studies and time can solve.[16]