An epidemiological investigation was immediately conducted among all the inpatients assisted at the neurorehabilitation department. Among the 21 inpatients screened for SARS-CoV2 with rt-PCR on a nasopharyngeal swab, 13 patients were found to be positive (2 o 3 genes where detected).

Patients hospitalized in intensive neurorehabilitation settings following neurological damage, subsequently developing COVID-19 during their hospitalization, have not yet been reported. Such patients are elderly, with severe disabling neurological syndromes and more likely have significant underlying comorbidities; consequently, they are particularly susceptible to infections and to develop fatal complications during their hospitalization.

Here we report outcomes and clinical features of a cohort of 14 patients affected by severe sensorimotor disabilities who had been admitted to the Neurorehabilitation Unit of the IRCCS Neuromed Research Institute in Pozzilli, Italy, and subsequently found to be positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection on nasopharyngeal swabs.

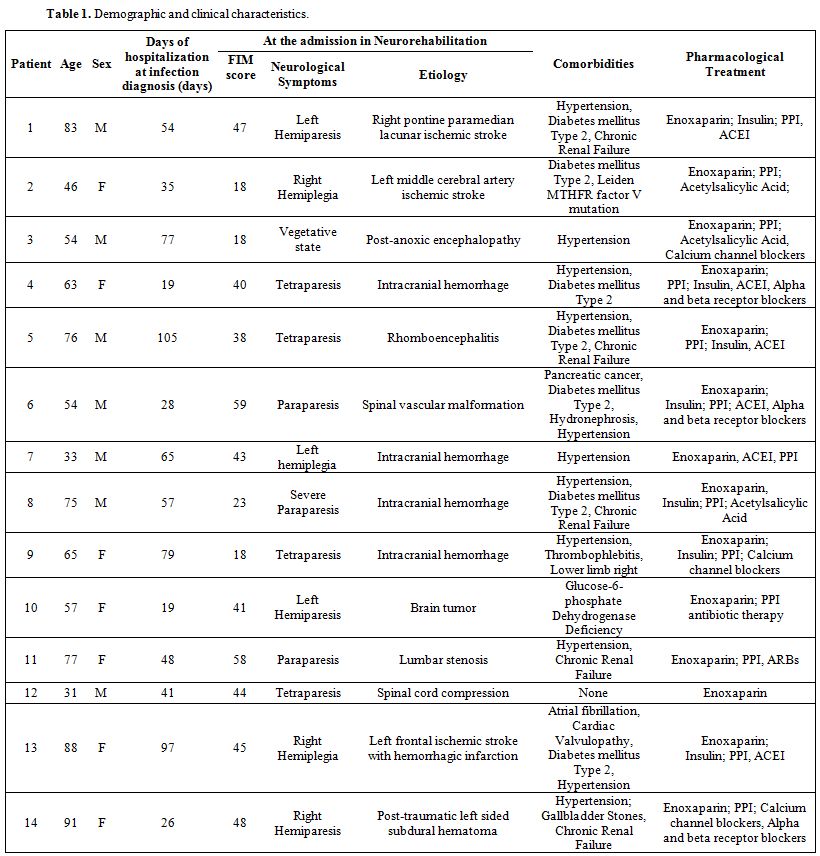

Patients’ demographic characteristics, clinical disability, neurological syndromes and etiology, comorbidities, and pharmacological treatments before SARS-CoV-2 infection are summarized in Table 1. The patient group consisted of 7 men and 7 women, mean age 63.8 years (range from 33 to 91 years). Eight out of 14 patients (57%) were older than 60 years. The mean FIM score was 38.6 (range from 18 to 59). The mean days of hospitalization at the moment of infection diagnosis were 53.7 (range from 19 to 105 days). Neurological symptoms were due to intracranial hemorrhage (35.7%), cerebral ischemic stroke (21.4%), spinal vascular malformations (7.1%), brainstem encephalitis (7.1%), brain tumors (7.1%), post-anoxic encephalopathy (7.1%), post-traumatic cervical myelopathy (7.1%) and severe spinal lumbar stenosis (7.1%). Thirteen out of 14 patients had comorbidities (93%), the most frequent being hypertension (11 patients, 78.5%), and type 2 diabetes mellitus (7 patients, 50%). Eleven out of 14 patients were already on treatment with antihypertensive drugs (irbesartan, ramipril, α and β-blockers, calcium antagonists), and 7 patients received insulin therapy. All patients had been treated since the beginning of the hospitalization with enoxaparin (40 mg daily) for thromboembolism prophylaxis.

|

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics. |

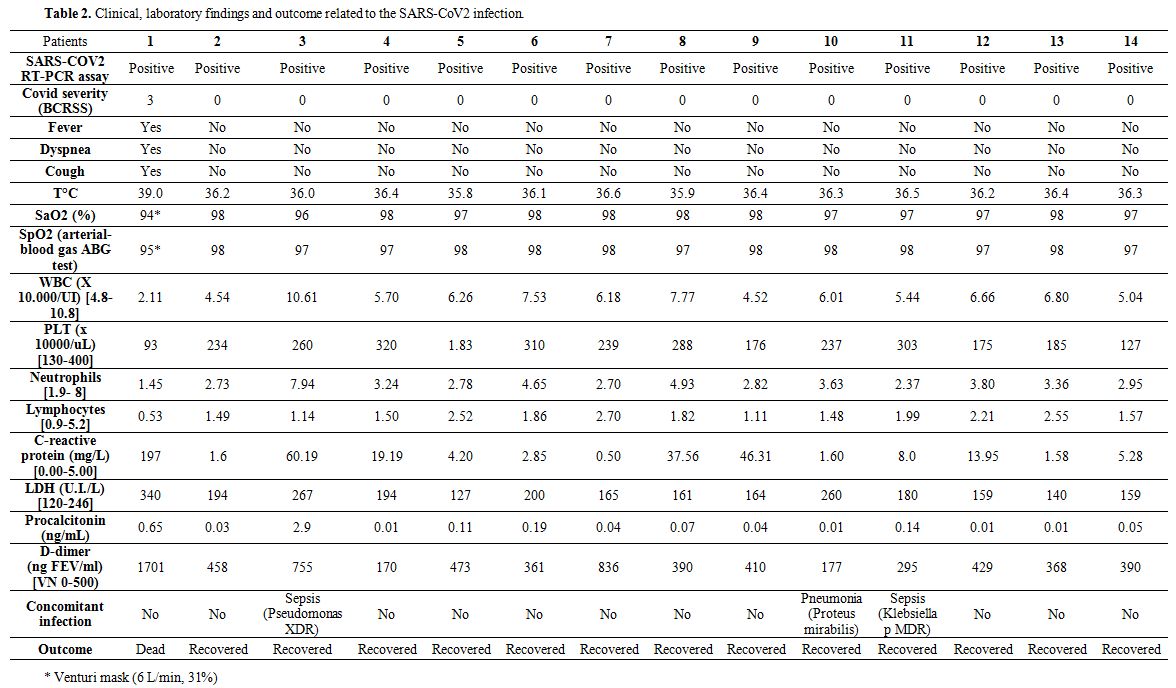

COVID severity, laboratory findings, clinical parameters related to SARS-CoV2 infection, concomitant bacterial infections, and pharmacological treatment are reported in Table 2. One out of 14 patients (7%) developed severe manifestations of COVID-19 (BCRSS=3) starting with fever, cough, and dyspnea, followed by a rapidly evolving acute respiratory distress syndrome ending with his exitus. All the other patients did not present fever, respiratory symptoms, or oxygen desaturation on both pulse oximetry and blood gas analysis (BCRSS=0). The symptomatic patient’s blood samples showed low white blood cell counts with lymphocytopenia, thrombocytopenia, elevated levels of C-Reactive Protein, lactate dehydrogenase,

|

Table 2. Clinical, laboratory findings and outcome related to the SARS-CoV2 infection. |

Procalcitonin, and D-dimer. In 10 out of 14 patients, blood tests were within normal values, whereas 3 out of 14 patients during the COVID-19 course presented fever and blood tests alterations suggestive of concomitant bacterial infection, as confirmed by microbiological tests of blood, sputum, and urine. In particular, one Pseudomonas aeruginosa XDR bloodstream infection, one bacterial pneumonia caused by Proteus mirabilis, and one urinary tract infection caused by KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae were resolved after specific antimicrobial treatment. This symptomatic patient required Venturi mask oxygen therapy (flow rate of 6 L/min at 31%) and was the only one treated with antiviral (Lopinavir/Ritonavir, 100/25 mg twice daily) and an antimalarial drug (hydroxychloroquine, 200 mg twice daily) in accord with Italian guidelines.[6] Asymptomatic patients were not given any currently used anti-covid drugs except for enoxaparin; the latter was continued for antithrombotic prophylaxis. After 24 hours, the symptomatic patient was transferred to the regional reference center for COVID-19, were he died after 72 hours.

In the surviving patients, neither new neurological deficits nor worsening of the pre-existing ones were observed. No patient developed hemorrhagic complications.

A thin-slice chest CT scan was performed in all patients. In the symptomatic patient, bilateral areas of ground-glass opacities with crazy-paving pattern occurred in a multilobar distribution. In contrast, the other patients did not present any radiological finding compatible with interstitial pneumonia.

SARS-CoV-2 clearance was assessed in all the surviving patients by repeatedly negative testing on RT-PCR performed within 45 days after the initial positive test.

Clinical features and risk factors of COVID-19 are highly variable, making the clinical severity ranging from asymptomatic to fatal. Symptoms comprise fever, fatigue, dry cough, dyspnea, myalgia, headache, diarrhea, rhinorrhea, and sore throat.[1] Associated medical conditions include hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes mellitus. The majority of patients show decreased lymphocyte count, prolonged prothrombin time, and increased lactate dehydrogenase and C-Reactive Protein levels.[1-2] In vitro qualitative detection of SARS-CoV-2 in respiratory samples by RT-PCR represents the reference standard for diagnosis.[3] However, RT-PCR sensitivity could be negatively influenced by inappropriate sampling procedures and insufficient virus load, high false-negative rate, and low sensitivity during the early phases of the disease.[4-5]

Older age and comorbidities represent potential risk factors for SARS-CoV-2 infection and are reportedly associated with a worse disease course and increased mortality rate.[6] In our patients, the virus was mostly asymptomatic, and this is particularly intriguing, also considering their previous severe disabling clinical profile. A possible explanation for this surprising finding could be that all patients were treated with enoxaparin for thromboembolism prophylaxis, as it is used in patients with prolonged immobility. In fact, all our patients were all bedridden due to their severe neurological disability, and enoxaparin treatment was started already at the beginning of their hospitalization, long before the SARS-CoV-2 infection. In patients with severe COVID-19 significant abnormalities of coagulation with hypercoagulability, elevated D-dimer, prolonged prothrombin time, and reduced fibrinogen and platelet levels have been described.[7] Coagulopathy increases the risk of thromboembolism and disseminated intravascular coagulation, and non-surviving patients develop micro-thrombosis in the pulmonary circulation and peripheral cyanosis.[8] Early anticoagulant therapy with low molecular weight heparin has been suggested as a useful treatment, since it is associated with decreased mortality in severe cases, especially in those with very high D-dimer levels.[7-8]

Nevertheless, the efficacy of anticoagulant treatment in COVID-19 has not yet been validated by randomized trials. To explain the very unusual benign disease course in our patients, we speculate that enoxaparin, administered at standard prophylactic dosages for long periods before SARS-CoV-2 outbreak, could have exerted its beneficial effects possibly by a two-fold mechanism: anticoagulant, limiting the harmful impact of the disease and anti-inflammatory against the so-called cytokine storm, thus preventing the severe manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Our interpretation is supported by the finding that enoxaparin inhibits cytokine release in various inflammatory conditions.[9] Several studies showed that LMWH improves the coagulation dysfunction of COVID-19 patients and exerts anti-inflammatory effects by reducing IL-6 and increasing percent lymphocytes. It appears that LMWH might have a central role in the treatment of COVID-19, paving the way for a subsequent well-controlled randomized clinical trial. Furthermore, antiviral activity of enoxaparin was hypothesized and supported by recent studies.[10-11] Nevertheless, the risk of bleeding complications from anticoagulant therapy in patients with SARS CoV2 infection should not be underestimated.[12]

Notably, 6 out of 14 patients were given ramipril, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI), and one patient was treated with irbesartan, an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB). Although the use of ARBs has been suggested as a possible treatment for reducing the disease severity of COVID-19,[13] both ACEIs and ARBs may increase ACE2 receptors expression in cardiopulmonary circulation; their use may potentially enhance the risk of developing severe disease outcome in COVID-19.[14]

In conclusion, despite the small number of patients and a control group not treated with heparin, our data suggest that hospitalized, vulnerable, patients with severe neurological damage can present a completely unexpected benign disease course after SARS-CoV-2 infection, representing an interesting patient group to investigate the pathogenetic mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 further. The anti-inflammatory and anticoagulant effects of enoxaparin administered much earlier before and during the infection, together with a possible antiviral activity, could explain the favorable disease course observed in these severe neurological patients with increased risk of poor outcome. Further research is needed to explore the possible mechanisms of action of enoxaparin in critical neurological patients with COVID-19 and confirm our observations.