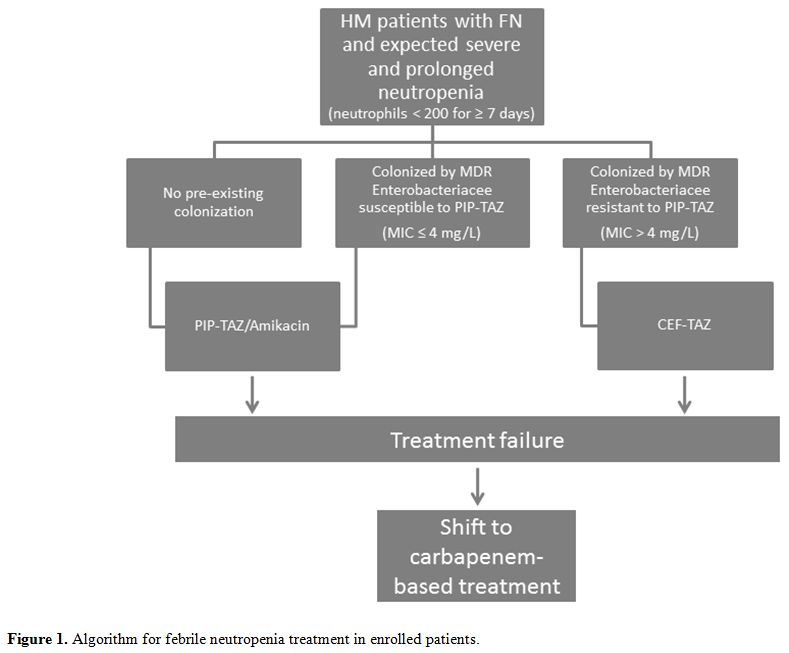

From Feb-2018, all consecutively hospitalized H.M. patients aged ≥ 18 years with an expectation of severe (< 200 neutrophils/mcL) and prolonged (≥ 7 days) neutropenia were enrolled in the study (mainly acute leukemias and stem cell transplants). All patients were screened at admission for M.D.R. microorganism colonization by rectal, nasal, pharyngeal, urethral/genital, and central venous catheter exit-site swabs and by urine and blood cultures, according to institutional guidelines. The algorithm proposed for F.N. treatment is summarized in Figure 1. Briefly, patients colonized by multi-resistant Enterobacteriaceae resistant to PIP-TAZ (M.I.C.> 4 mg/L) were treated with CEF-TAZ monotherapy (investigational cohort). In contrast, not colonized patients underwent our standard antibiotic approach based on PIP-TAZ/Amikacin, including patients colonized by multi-resistant Enterobacteriaceae susceptible to PIP-TAZ (M.I.C. ≤ 4 mg/L) (not colonized cohort). A third group consisted of a historical cohort of patients (admission to our Unit between Jan-2016 and Jan-2018), which were colonized by multi-resistant Enterobacteriaceae resistant to PIP-TAZ and were handled with PIP-TAZ/Amikacin at F.N. onset (historical control cohort). None of the enrolled patients was treated with fluoroquinolones as neutropenia prophylaxis, according to our current institutional policy. Patients colonized by carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae strains were excluded from this study. Criteria for initial treatment failure and shift towards a carbapenem-based treatment included persistent fever associated with one of the following signs occurring within 24-72 hours from the onset: 1) hemodynamic instability; 2) rapid respiratory distress; 3) rapid clinical deterioration. B.S.I., sepsis, and septic shock were defined according to the Surviving Sepsis Campaign criteria.[4] The M.A.S.S.C. score for F.N. risk was used to assess the severity of the patient's clinical presentation.[5] The end-organ disease was defined as parenchymal dissemination due to the same microorganism causing B.S.I. In particular, pneumonia etiology was documented by performing a bronchoalveolar lavage fluid analysis, as previously described.[6] The study was approved in the context of an institutional antimicrobial stewardship program (PT-DSA-01-2019-rev.0) and was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki declaration. All enrolled patients signed informed consent for data analysis for scientific purposes.

|

Figure 1. Algorithm for febrile neutropenia treatment in enrolled patients. |

Bacterial identification was performed by using the MALDI-TOF MS system (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany). Antibiotic susceptibility was tested through the use of the VITEK®2 system (bioMérieux, Marcy-l'Etoile, France) and the broth microdilution test (Thermo Scientific, Massachusetts, U.S.A.) was used for defining the M.I.C. criteria, according to the European on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (E.U.C.A.S.T.) interpretative standards (www.eucast.org).[7]

The primary end-point was the failure rate of CEF-TAZ (leading to a shift toward a carbapenem) as a first-line monotherapy approach for F.N. in patients colonized by multi-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. To verify the hypothesis that CEF-TAZ was able to decrease the global shift rate toward a carbapenem from 35% to 10% with a power of 80% at a significance level of 5% (two-sided test), it was necessary to enroll 43 patients in this investigational cohort. The study started in Feb-2018. Herein we report an interim-analysis carried out two years after the beginning of the study, focused on the comparison of shift rates toward carbapenems among the three cohorts of patients (investigational cohort, historical control cohort, not colonized cohort). Secondary end-points were the rates of documented B.S.I. and end-organ disease, the severity of symptoms associated with F.N., and 30-day attributable mortality. Statistical analyses were carried out using the S.P.S.S. software (S.P.S.S. version 21, S.P.S.S. Inc., Chicago, IL, U.S.A.). A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

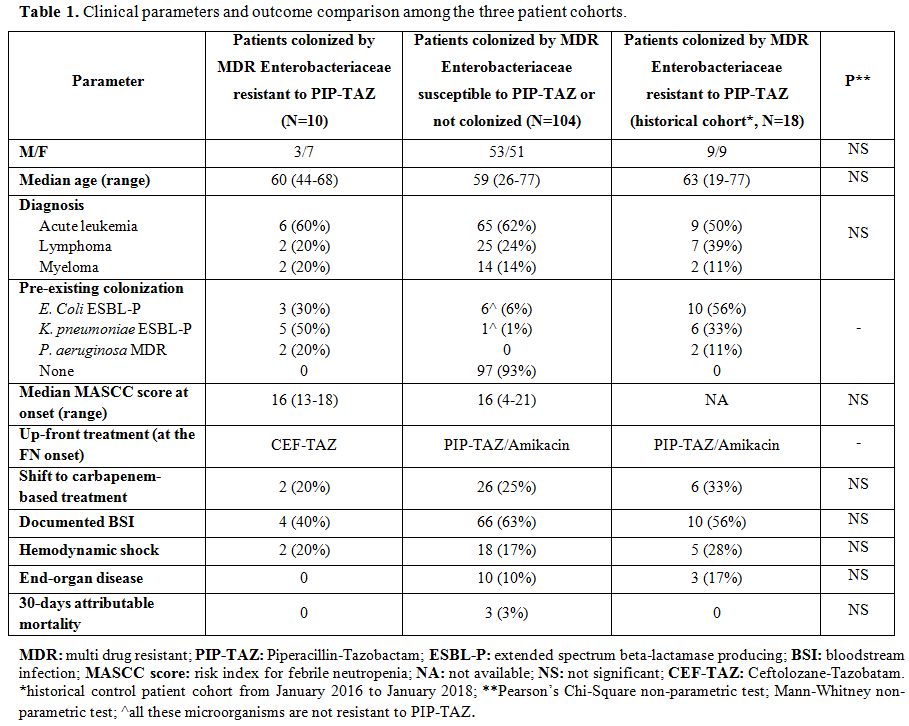

Ten patients were enrolled in the investigational cohort, 104 patients in the not colonized cohort, and 18 patients formed the historical control. Out of 114 patients who were consecutively enrolled in the two prospective cohorts, 17 (15%) presented pre-existing colonization by multi-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, whereas the remaining 97 were not colonized. Among the 17 colonized patients, 10 cases received CEF-TAZ at the F.N. onset, being colonized by multi-resistant Enterobacteriaceae with proven resistance to PIP-TAZ. In contrast, the remaining 7 patients received a standard antibiotic treatment based on PIP-TAZ /Amikacin, being colonized by multi-resistant Enterobacteriaceae susceptible to PIP-TAZ (Figure 1). In the 10 patients who received CEF-TAZ, all strains of colonizing multi-resistant Enterobacteriaceae proved to be resistant to PIP-TAZ and susceptible to CEF-TAZ. The 97 not colonized patients received PIP-TAZ/Amikacin. As for the primary end-point, the shift rate towards a carbapenem-based treatment in the group of patients treated with CEF-TAZ was 20%. As shown in Table 1, this rate was lower but not significantly lower than that observed in the not colonized cohort (25%) and in the historical control cohort (33%). As for the secondary end-points, at the F.N. onset, there were not any significant differences in terms of B.S.I., hemodynamic shock, end-organ disease, and 30-day attributable mortality (Table 1). In particular, 4 cases of B.S.I. were diagnosed in patients treated with CEF-TAZ, and in 2 out of these 4 cases, the isolated pathogen was the same one responsible for the pre-existing colonization (ESBL-P K. pneumoniae in both). Similar data were observed in our historical cohort, in which we reported 10 cases of B.S.I. with 4 of them characterized by the same pathogen responsible for the pre-existing colonization (ESBL-P E. Coli n=2, ESBL-P K. pneumoniae n=1, M.D.R. P. aeruginosa n=1). Finally, we did not notice any significant differences between the two groups in terms of antibiotic treatment duration (PIP-TAZO/Amikacin: 7 days, range: 1-14; CEF-TAZ: 6 days, range 3-11).

|

Table 1. Clinical parameters and outcome comparison among the three patient cohorts. |

Based on our epidemiological scenario, consisting of the prevalence of ESBL-P Enterobacteriaceae and M.D.R. P. aeruginosa and a low incidence of carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae, and based on data reporting that H.M. patients colonized by multi-resistant Enterobacteriaceae are at risk of developing colonization-related B.S.I. and early death, we decided to start a prospective cohort study using CEF-TAZ monotherapy at the F.N. onset in H.M. patients with previous colonization by M.D.R. pathogens, aimed to explore a potential carbapenem-sparing strategy, in adherence to the local antibiotic stewardship program. Several studies recently reported on the importance of adopting a carbapenem-sparing approach to reduce the pressure of carbapenem overuse, causing resistance.[8]

Even though we still have limited data on the use of CEF-TAZ in ESBL-P pathogens, this molecule appears to be a promising novel agent potentially able to modify the current antimicrobial approach.[8-9] Two years after the beginning of the study, fewer patients than expected were enrolled in the investigational cohort. The use of CEF-TAZ at the F.N. onset in H.M. patients colonized by ESBL-P Enterobacteriaceae and M.D.R. P. aeruginosa resistant to PIP-TAZ determined a shift rate toward a carbapenem of 20%, lower but not statistically significantly different than that observed in all other patients treated with the standard antibiotic approach.

Moreover, we did not observe any significant differences in all the other parameters and outcomes analyzed among the three patient cohorts, including attributable mortality. Even if, at the first interim-analysis, our study failed to reach the primary end-point, we believe that these results are relevant for at least three reasons. Firstly, there are only a few studies reporting data on the use of CEF-TAZ in H.M. patients,[10] and to our knowledge, there are still no published studies on CEF-TAZ for F.N. treatment. Secondly, a CEF-TAZ monotherapy was, however, able to decrease the carbapenem recourse rate in patients colonized by M.D.R. Enterobacteriaceae resistant to PIP-TAZ from 33% in the historical cohort to 20%, not enough to be statistically significant but enough to continue the study. Finally, a CEF-TAZ monotherapy was, however, able to equalize around 20-25% the carbapenem recourse rates between the colonized and not colonized patients, breaking down the additional risk given by the M.D.R. pathogens. In conclusion, given the limitation due to the low number of patients enrolled, CEF-TAZ monotherapy for F.N. treatment in H.M. patients colonized by ESBL-P Enterobacteriaceae and M.D.R. P. aeruginosa could be a promising carbapenem-sparing strategy. Further study is warranted to confirm these preliminary results.