Marco Cioce1, Franziska Michaela Lohmeyer2, Rossana Moroni2, Marinella Magini3, Alessandra Giraldi3, Paola Garau1, Maria Carola Gifuni1, Vezio Savoia4, Danilo Celli5, Stefano Botti6, Gianpaolo Gargiulo7, Francesca Bonifazi8, Fabio Ciceri9, Ivana Serra10, Maurizio Zega10, Simona Sica11, Andrea Bacigalupo11, Valerio De Stefano11 and Umberto Moscato12..

1 UOC

Ematologia e Trapianto di Cellule Staminali Emopoietiche, Fondazione

Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS, Roma, Italy.

2 Direzione scientifica, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS, Roma, Italy.

3 UOC Nutrizione clinica, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS, Roma, Italy.

4 Servizio di Psico-Oncologia, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS, Roma, Italy.

5 Facoltà di Medicina e Psicologia, Università “La Sapienza”, Roma, Italy.

6 UOC Ematologia, Azienda USL-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Italy.

7 UOC Ematologia, Università “Federico II”, Napoli, Italy.

8 Istituto di Ematologia “Seràgnoli”, Policlinico Universitario S.Orsola-Malpighi, Bologna, Italy.

9 IRCCS Ospedale San Raffaele, Milano, Italy.

10 Direzione SITRA, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS, Roma, Italy.

11 Istituto di Ematologia, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Roma, Italy.

12 Istituto di Sanità pubblica, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Roma, Italy.

Correspondence to: Marco Cioce, UOC Ematologia e Trapianto di

Cellule Staminali Emopoietiche, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario

Agostino Gemelli IRCCS, Largo Agostino Gemelli, 8 00168 Roma, Italy.

Tel.: +393472294176. E-mail:

marco.cioce@policlinicogemelli.it;

Published: September 1, 2020

Received: June 19, 2020

Accepted: August 16, 2020

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2020, 12(1): e2020067 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2020.067

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Background.

Physical and psychological factors, like wrong attitudes and

behaviours, can negatively influence the health outcomes of the

patients receiving allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

(AHSCT). Educational interventions aiming to improve knowledge on side

effects, risks, complications and preventive behaviour can reduce

psychological distress, and improve quality of life (QoL). We aimed to

compare a standard approach with therapeutic patient education (TPE) to

analyse the impact on AHSCT patients' QoL, psychological distress and

knowledge of AHSCT side effects, risks complications and preventive

behaviour.

Material and methods.

A prospective interventional study was conducted analysing data of 36

patients who received one of two different educational approaches,

which were a standard approach (not-exposed) or TPE (exposed).

Results.

In the exposed group QoL improved 14 days after transplantation (42.2

vs 25.6; p<0.03) and at time of discharge (36.6 vs 54.4;

p<0.005). Anxiety and depression were better controlled in the

exposed group, both at hospitalisation and discharge (anxiety: 48.1 vs

53.2; 46.4 vs 51.6. p<0.04; depression: 49 vs 55.3; 48 vs 54.3,

p<0.03). Knowledge of AHSCT risks and complications improved in

exposed patients, both at admission (10.1/15 vs 8/15 correct answers;

p<0.01) and discharge (10.7/15 vs 8.8/15 correct answer; p<0.03).

Conclusions.

The TPE for AHSCT patients improved knowledge, reduced anxiety and

depression, which consequently increasing QoL. Therefore, we recommend

our approach to further engage patients in the treatment plan, which

should specifically take place prior to AHSCT initiation.

|

Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (AHSCT) is the standard of care for several haematological disorders.[1]

AHSCT patients require hospitalisation in protected environments where

they follow appropriate antimicrobial prophylaxis and prevention

programs to overcome the toxic effects of the therapy minimising

associated risks. However, non-relapse mortality at two years ranges

between 15% and 40%, and it depends on the patients' age,

comorbidities, disease, status at transplant, conditioning regimen and

donor type.[2] Survival at two years ranges between 50% and 80%.[3]

AHSCT

is associated with health problems occurring in the immediate

post-transplant period including infections, bleeding, mucositis,

fever, nausea, hypotension and shock, skin rash, acute or chronic pain

and diarrhea[4] which can negatively affect patients' QoL and survival.[5]

In

addition, patients undergoing an AHSCT can present relevant

psychological distress - most common depression, anxiety and sleeping

problems - they might confront with primitive defence mechanisms such

as denial, and projection.[6] Depression is the most common manifestation of psychological distress in patients with neoplastic disease;[7-9] which is even more frequent in patients with advanced disease.[10-12]

AHSCT

requires that patients and their families change their daily life.

Patients and their caregivers can reinforce their knowledge on

necessary lifestyle changes following specific therapeutic, educational

interventions, increasing patient engagement, collaboration with

healthcare-worker, knowledge of the disease and treatment, and QoL,

which can positively impact their health outcomes.[13,14]

The

use of audio-video and information material for individual learning

accompanied by verbal instructions, complemented by multidisciplinary

and interactive educational teaching tools notably improved knowledge

and practical skills.[15] Currently, no studies exist

in the literature, which systematically assessed the relationship

between therapeutic education and health outcomes in AHSCT.

This

study aimed to compare a standard with therapeutic patient education

(TPE) analysing the impact on QoL, psychological distress and knowledge

of AHSCT side effects, risk factors, complications as well as

preventive behaviour.

Materials and Methods

Study design. This is an interventional, randomised (computer-generated, 1:1), double-blind study with two groups:

• Not-exposed

group. Standard approach, printed informative material about the

transplant procedure, complications, self-care, general advice, diet

and safety issues, was delivered at the time of hospitalisation by the

primary nurse;

• Exposed group. TPE conducted by a nurse, a dietician and a psychologist.

Patients have been randomised in the two groups immediately after singing written informed consent.

The study was approved by the local ethics committee on January 18, 2018 (Prot. 46787/17 – 1143/18, ID: 1767).

Inclusion/exclusion.

Thirty-six patients undergoing AHSCT at our hospital (central Italy)

were involved in the study from May to December 2018, of them the half

came from other centres of Italy. All participants were adults (over 18

years) of both sexes and able to provide written informed consent.

Exclusion criteria were the following: patient uncooperative and/or

affected by mental disease, pregnant or breastfeeding women.

Sample size calculation.

The sample size was calculated considering a mixed model ANOVA with

repeated measures, with alpha=0.01 and power 80%, delta=0.6325 on two

groups; and variance between groups=0.0200 and a variance

"between-within groups" =0.05 for two or more repeated measures with a

correlation index rho=0.9. Considering a possible drop-out, we

recruited 36 patients (18 patients in each group).

Therapeutic patient education. The TPE, based on a WHO working group report,[16]

taking place about a week before transplant hospitalisation, including

an interview of about 60 minutes in which the patient and the caregiver

participated and verbal instructions were provided on the following

areas:

• Nursing care. During the meeting, nurses

addressed detailed AHSCT side effects, risks, complications and

preventive behaviour responding on arising questions; a video of about

10 minutes was projected explaining main complications, hand hygiene,

protective isolation and lower microbial load rooms (video

surveillance, health call etc.). Additionally, printed informative

material (mucositis, hand hygiene, access mode, recommendations and

prohibitions, multi-resistant germ brochures as well as an allogeneic

transplant guide) was handed out and explained.

• Psychological.

Most frequent psychological problems (anxiety and depression) in the

onco-haematological area and possible interventions were addressed; a

psycho-oncologist with several years of experience answered raised

questions.

• Nutritional. Educational intervention

according to guidelines of the International Agency for Research on

Cancer (IARC) and the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and

Metabolism (ESPEN) for cancer patients. Data collected in the

nutritional education area evaluating caloric-proteic malnutrition in

patients undergoing AHSCT is not part of this publication.

Outcome measures.

The 36 patients observed were evaluated for QoL with the Cancer Linear

Analogue Scale (CLAS) at time of admission (T0), day of the AHSCT (T1),

7 and 14 days after the AHSCT (T2/T3) as well as at discharge (T4).

CLAS investigates energy level, ability to perform daily activities and

overall QoL.

The Symptom Checklist-90-R (SCL-90-R) was performed

at T0 and T4, assessing symptom severity of psychological distress in

the week before checklist performance. The patient's responses are

interpreted based on nine primary symptomatological dimensions

(cut-off≥55).

The degree of knowledge regarding concepts addressed

during the TPE was assessed through a structured multiple-choice

questionnaire at T0 and T4, which was composed of 15 items, 5 for each

profession involved. The reliability of the internal consistency has

been tested through the alpha Cronbach and the validity of the content

through the Content Validity Index.[17] The internal consistency of the instrument used, measured by calculating the alpha of Cronbach, was 0.83.

Statistical analysis.

The sample was described in its socio-demographic and clinical

characteristics through descriptive statistic techniques. Qualitative

variables have been described using absolute frequencies and

percentages, while quantitative variables have been summarised through

the range, mean, median and standard deviation. Normality of data was

verified with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Comparisons were performed with

t-tests for paired data or Kruskal-Wallis, for nonparametric variables.

Mixed model ANOVA and generalised linear model, where the

between-subjects factor was represented by two groups (exposed and

not-exposed) and the within-subjects factor is represented by the

time was used for repeated measurements.[18]

Bonferroni correction was applied. Data have been stored and managed in

spreadsheet (Data set created on a Microsoft Excel 2016 spreadsheet for

Mac Vers. 2016/14.5.5). Statistical analyses were carried out with

Stata7IC software[ 14.2 for Mac (64-bit Intel), Vers. January 09 2017,

800-STATAPC- Lakeway]. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

Of

36 patients included in the study, 18 have been randomised to the

not-exposed group (50.0%), with 40% (7/18) coming from other centres,

and 18 have been randomised to the exposed group (50.0%), with 60%

(11/18) from other centres. The proportion of missing data at the end

of the study was minimal (<5%). The sample consisted mainly of male

patients (n=22, 61.1%), most of them in the not-exposed group (83.3% of

males in the group) while 61.1% of patients in the exposed group were

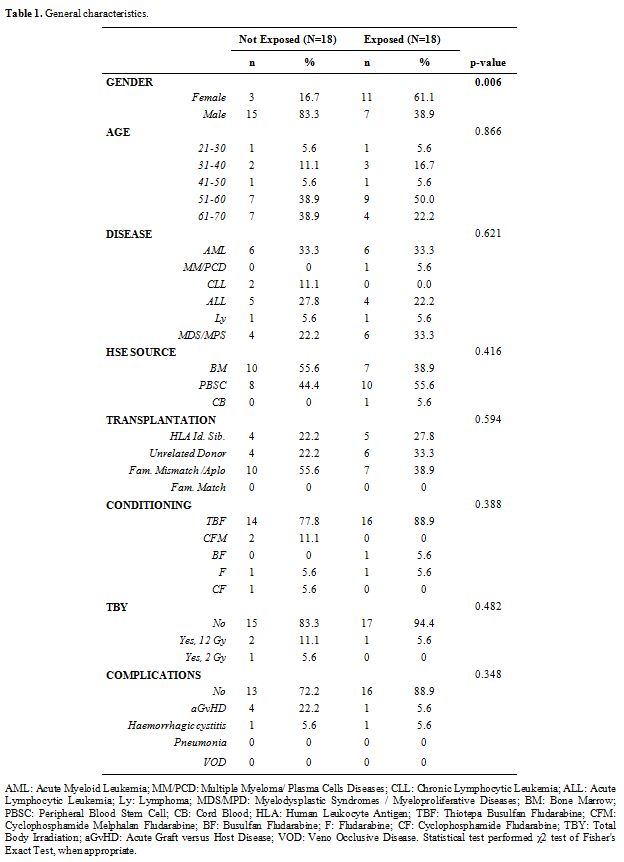

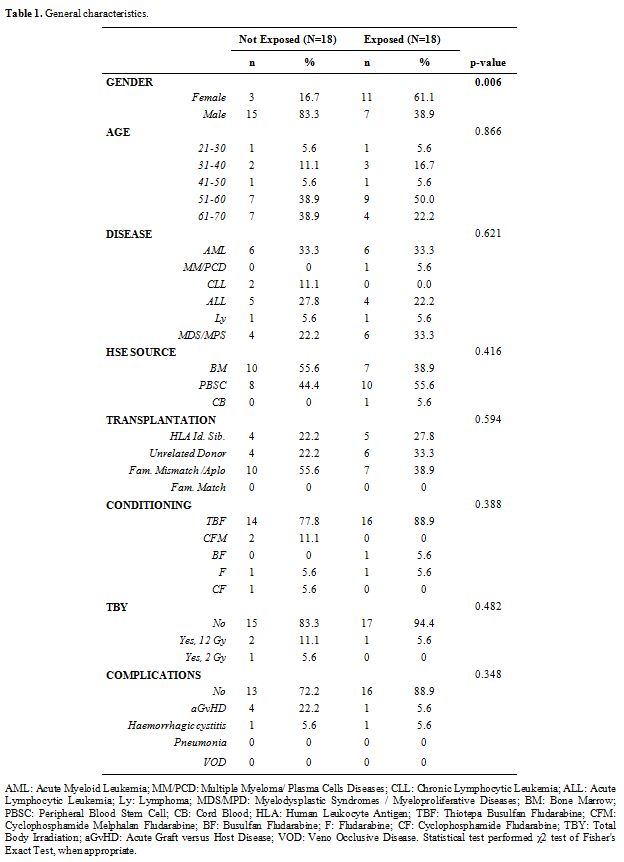

females, p=0.006. Table 1 describes the clinical and demographic characteristics of the cohort.

|

Table 1. General characteristics. |

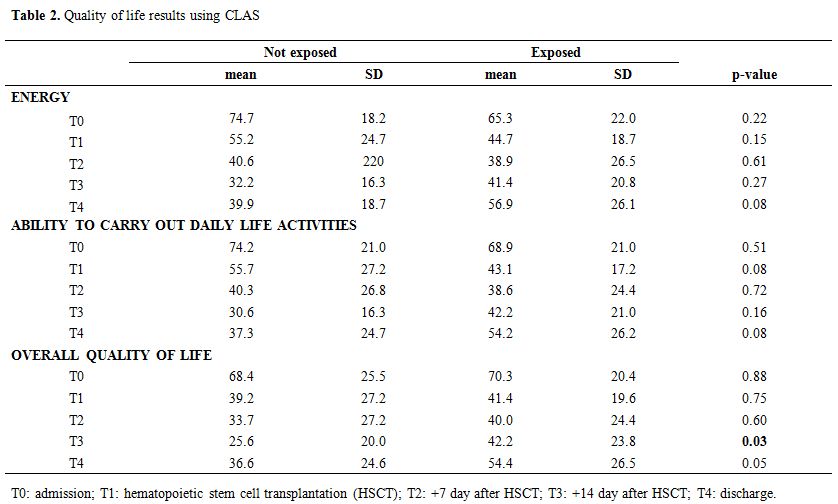

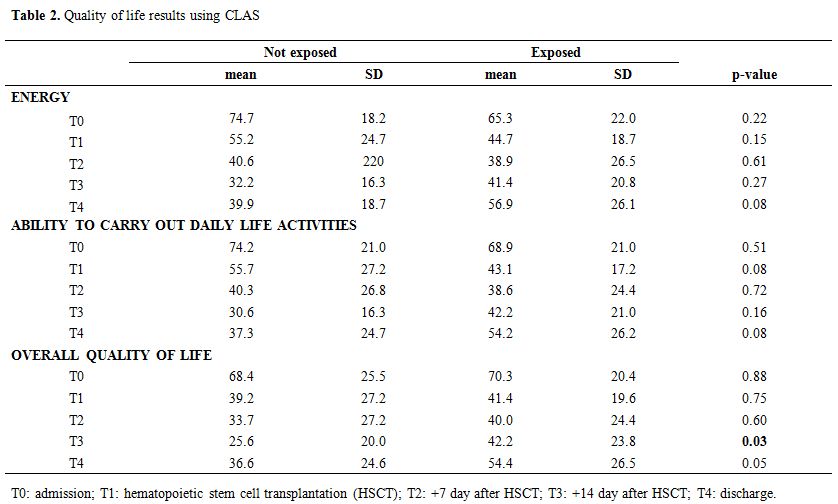

Table 2

demonstrates the results regarding QoL assessed with CLAS. The exposed

group had statistically significant (p=0.03) better scores 42.2 versus

25.6 (not-exposed group) at T3 (14 days after AHSCT) when questioned

about their general QoL. The difference between the two groups was more

significant at discharge: 36.6 (exposed) and 54.4 (not exposed),

p=0.05.

|

Table

2. Quality of life results using CLAS |

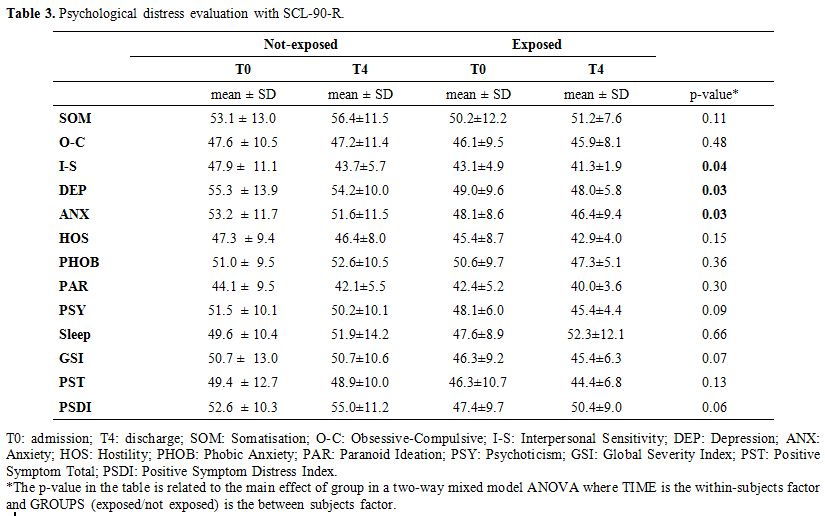

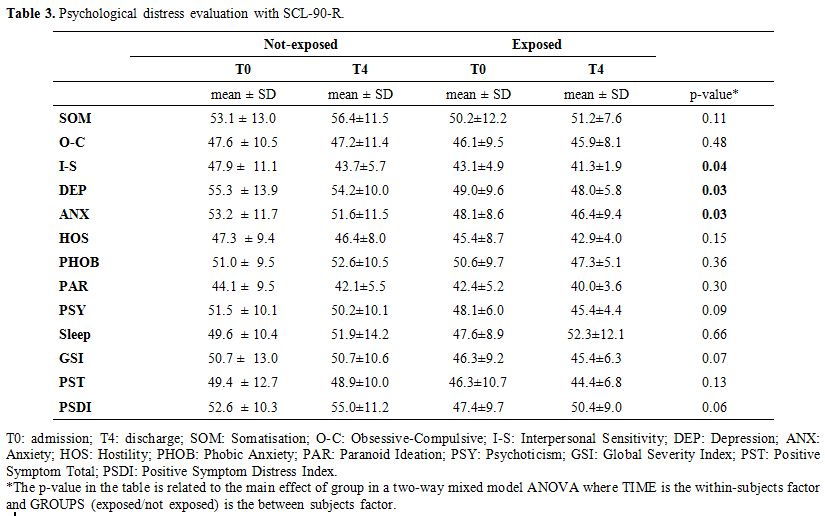

Regarding

psychological distress assessed with SCL-90-R, statistically

significant results have been highlighted in the area of interpersonal

hypersensitivity (I-S) where the main effect of group's p-value was

0.04. More detailed, in the not-exposed group, the mean discomfort

related to T0 was 47.9 (±11.1) and was 43.7 (±5.7) in T4. In the

exposed group, the mean discomfort was 43.1 (±4.9) and was 41.3 (±1.9)

in T4. For the areas anxiety (ANX) and depression (DEP), all patients,

exposed and not-exposed had symptoms at T0 and T4, whose intensity did

not deviate from the average values found in the reference sample. The

anxiety score (ANX) decreased from 53.2 to 51.6 in not-exposed patients

and from 48.1 to 46.4 in exposed patients (groups main effect p=0.03).

The DEP score increased from 55.3 to 54.2 in not-exposed patients and

decreased from 49 to 48 in exposed patients (groups main effect

p=0.03). Although the p-value was not significant, it is important to

underline that, in the area of paranoid ideation (PAR), no elements of

discomfort are highlighted at both T0 and T4; the score decreased from

44.1 to 42.1 in not-exposed patients and from 42.4 to 40 in exposed

patients (Table 3).

|

Table 3. Psychological distress evaluation with SCL-90-R.. |

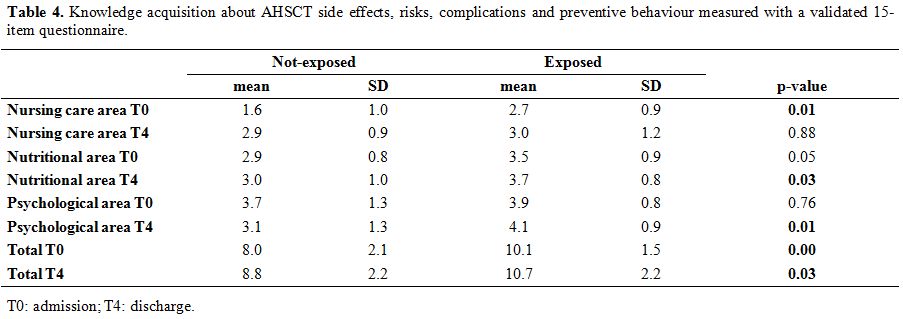

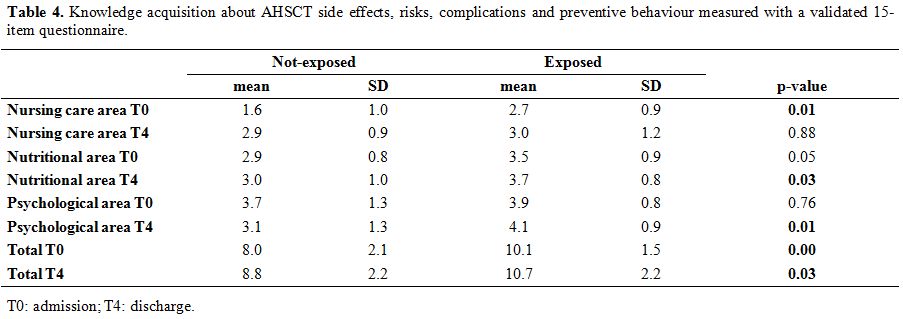

Table 4

shows the results of the 15-item questionnaire about knowledge

acquisition in the three areas (nursing care, psychological and

nutritional). Both total scores at T0 and T4 were statistically

significant, demonstrating increased awareness in the exposed group

compared with the not-exposed group. More detailed, the correct answers

given, at T0 in the exposed group were 10.1/15 compared with 8/15 in

the not-exposed group (p<0.0); instead, at T4, results were 10.7/15

in the exposed group compared with 8.8/15 in the not-exposed group

(p<0.03).

|

Table 4. Knowledge

acquisition about AHSCT side effects, risks, complications and

preventive behaviour measured with a validated 15-item

questionnaire. |

Discussion

Our

data demonstrate that the TPE, taking place about a week before

transplant hospitalisation, statistically significant improved

patients' knowledge of AHSCT side effects, risks, complications as well

as preventive behaviour. Further, we demonstrated that knowledge gain

reduced psychological distress, improving QoL in our cohort.

More

detailed, we noted statistically significantly increased knowledge in

the total scores of the exposed group compared with the not-exposed

group, both at T0 (p=0.0) and T4 (p=0.3). We based the development of

our TPE on findings by Friedman et al. (2011)[19] who

reinforced the thesis that teaching strategies using audio-video

presentations, verbal instructions and personalised information

material, assuring an appropriate level for independent study, are more

effective than traditional methods to improving knowledge and behaviour

of patients. Bennet et al. (2016)[20] evaluated

educational strategies in adult cancer patients, in a systematic review

of 14 randomised clinical trials, which showed that the integration of

different educational modalities is effective to reduce fatigue and

anxiety improving overall QoL.

Furthermore, we noted that the

nursing care score at T0 was statistically significant (p=0.01) whereas

at T4 not (p=0.88); this might be explainable with the intense training

and information the exposed group received during the TPE by nurses. To

improve our approach further, we suggest repeating parts of the

teaching during hospital admission to ensure that preventive behaviour

and attitudes will be remembered.

Likewise, we noticed that

psychological distress was significantly improved at T4 (p=0.01), but

not at T0 (p=0.76). This result can be explained that the intervention

of different health workers, during the TPE, reduces uncertainties of

the transplantation path, which positively impacts the patient's

psychological state.

Our conclusions can be further confirmed with

data on psychological distress assessed with SCL-90-R. We showed

significant differences between the two groups in the areas ANX and

DEP. Patients of the exposed group, compared to the not-exposed group,

showed that they went through the therapeutic journey with a lower

level of fear, worry and demoralisation. The TPE allows the patient an

adequate containment of potential distress such as fear, worrying and

sadness, making the state of anxiety and depression not requiring

specialist psychotherapeutic and psychiatric interventions. This result

has been obtained through description, explication and instruction of

the possible risks associated with admission to a lower microbial load

room and possible side effects of AHSCT treatment. These data are in

accordance with the results by Fawzy et al. (1993)[21]

who demonstrated that the intervention of a 6-week psychotherapeutic

group - including educational interventions as psychological support,

stress management and development of coping skill - was associated

with lower mortality in patients with malignant melanoma after six

years follow-up. Donker et al. (2019)[22] evidenced

that psychological education (information, teaching material and

advice) reduced levels of psychological distress and specifically

depression.

Related to reduced psychological distress, before

and during AHSCT, is the improvement of QoL. Data collected show that

the TPE for patients and their caregivers reduced psychological

distress and improved statistically significant QoL (p=0.03) at T3

assessed with CLAS. Several studies confirm that educational

interventions improve knowledge of AHSCT and QoL in the long term.[23] Kirsch et al. (2012)[24]

demonstrated the effectiveness of educational/therapeutic

interventions, which acted synergistically, on the strengthening of

problem-solving during treatment and follow-up. Instead, Marques et al.

(2012)[25] showed that QoL, measured with QLQ-C30,

has lower average scores in the pancytopenia compared to the

pre-transplant phase. This is probably due to the critical moments of

treatment when complications can occur, endangering patients’ lives or

interfering negatively with their QoL. Accordingly, we recorded lower

average values, which were even lower in the exposed group, both at T3

and T4. After hospitalisation, a progressive improvement to perform

daily activities and QoL, equal if not better than in the

pre-transplant phase, is usually expected between 9 to 12 months, even

if a percentage of patients suffering from late complications, such as

chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease (GvHD), reach the pre-transplant

level.[26]

Limitations

Among

our limitations is the relatively small, but notwithstanding adequate

sample size. According to our protocol, patients were randomly assigned

and which led to more women in the exposed group. Furthermore, data is

not generalisable to other contexts. Therefore, our study necessitates

confirmation on a larger cohort and replication in different settings

always in the context of AHSCT.

We do not know if the point in

time providing the two different approaches might have influenced our

results; exposed patients had one-week time in their familiar

surroundings to process the received information after they

participated on the TPE compared with the not-exposed group, which

received printed material at the time of hospitalisation. This aspect

was not investigated in our study.

Conclusions

In

conclusion, therapeutic education is a relevant aspect of clinical

pathways. Although several studies describe its usefulness in some

areas, evidence to support its effectiveness in AHSCT is lacking.

Obtaining information through educational interventions is a

fundamental right for patients undergoing AHSCT. We hope this approach

will spread widely as an educational methodology structured in a

multidisciplinary development perspective of real patient care and its

centrality in the care processes. The results of this study show that a

TPE before AHSCT improved knowledge on AHSCT side effects, risks,

complications and preventive behaviour, which reduced in our cohort

anxiety and depression positively affecting QoL. Based on our data, we

recommend engaging patients in AHSCT treatment as much and as early as

possible, allowing an active role in decision-making processes, which

improves adequate self-care. Furthermore, we believe that it might be

positive if the AHSCT topics addressed before hospitalisation are

repeated during admission, based on individual needs and capacities.

The

effectiveness of TPE in AHSCT should be confirmed in future multicentre

study in the GITMO group (Gruppo Italiano per il Trapianto di Midollo

Osseo, cellule staminali emopoietiche e terapia cellulare).

References

- Tura S. Corso di malattie del sangue e degli organi emolinfopoietici. 6 Ed., Bologna, Società Editrice Esculapio. 2015;377-387. https://doi.org/10.15651/978-88-748-8884-9

- Tanaka

Y, Kurosawa S, Tajima K, Tanaka T, Ito R, Inoue Y, Okinaka K, Inamoto

Y, Fuji S, Kim SW, Tanosaki R, Yamashita T, Fukuda T. Analysis of

non-relapse mortality and causes of death over 15 years following

allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow

Transplantation. 2016;51:553-559. https://doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2015.330 PMid:26752142

- Mosesso

K. Adverse Late and Long- Term Treatment Effects in Adult Allogeneic

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Survivors. American Jurnal of

Nursing. 2015;115(11):22-34. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000473311.79453.64 PMid:26473441

- Cioce

M, Moroni R, Gifuni MC, Botti S, Orlando L, Soave S, Serra I, Zega M,

Gargiulo G. Relevance of NANDA-I diagnoses in patients undergoing

haematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a Delphi study. Professioni

Infermieristiche. 2019;72(2):120-128.

- Kim

I, Koh Y, Shin D, Hong J, Jae Do H, Kwon SH, Sik Seo K. Importance of

Monitoring Physical Function for Quality of Life Assessments in

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Patients: A Prospective Cohort

Study. In vivo;34:771-777. https://doi.org/10.21873/invivo.11837 PMid:32111783 PMCid:PMC7157879

- Holland JC. Psychological Care of Patients. Psycho-Oncology's Contribution. J Clin Oncol, 2003;21:253s-265s. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2003.09.133 PMid:14645405

- Akechi

T, Nakano T, Okamura H, Ueda S, Akizuki N, Nakanishi T, Uchitomi Y.

Psychiatric disorders in cancer patients: Descriptive analysis of 1721

psychiatric referrals at two Japanese cancer center hospitals. Japanese

Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2001;31:188 - 194. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hye039 PMid:11450992

- Kugaya

A, Akechi T, Okuyama T, Nakano T, Mikami I, Okamura H, Uchitomi Y.

Prevalence, predictive factors, and screening for psychologic distress

in patients with newly diagnosed head and neck cancer. Cancer.

2000;88:2817-2823. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(20000615)88:12<2817::AID-CNCR22>3.0.CO;2-N

- Okamura

H, Watanabe T, Narabayashi M, Katsumata N, Ando M, Adachi I, Uchitomi

Y. Psychological distress following fi rst recurrence of disease in

patientswith breast cancer: Prevalence and risk factors. Breast Cancer

Research and Treatment. 2000;61:131 - 137. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006483214678 PMid:10942100

- Bukberg J, Penman D, Holland JC. Depression in hospitalised cancer patients. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1984;46:199 - 212. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-198405000-00002 PMid:6739680

- Longobardi

Y, Savoia V, Bussu F, Morra L, Mari G, Nesci DA, Parrilla C, D'Alatri

L. Integrated rehabilitation after total laringectomy: a pilot trial

study. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(9):3537-3544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-4647-1 PMid:30685792

- Carlson

LE. Screening alone is not enough: The importance of appropriate

triage, referral, and evidence-based treatment of distress and common

problems. J Clin Oncol, 2013;31:3616-3617. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.51.4315 PMid:24002494

- Assal JP, Golay A. Patient education in Switzerland: from diabetes to chronic diseases. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;44(1):65-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0738-3991(01)00105-7

- Bevans

M, Castro K, Prince P, Shelburne N, Prachenko O, Loscalzo M, Zabora J.

An Individualized Dyadic Problem-Solving Education Intervention for

Patients and Family Caregivers During Allogeneic HSCT: A Feasibility

Study. Cancer nursing. 2010;33(2):24-33. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181be5e6d PMid:20142739 PMCid:PMC2851241

- Foltz

A, Sullivan J. Reading level, learning presentation preference, and

desire for information among cancer patients. Journal of Cancer

Education. 1996;11:32-38.

- World Health

Organization. Europe Report Therapeutic Patient Education - Continuing

Education Programmes for Health Care Providers in the Field of Chronic

Disease. Copenhagen, Denmark: WHO; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fain AJ. La ricerca infermieristica: leggerla, comprenderla e applicarla. 2 Ed., Milano: McGraw-Hill. 2004;125.

- Moscato

U, Poscia A, Gargaruti R, Capelli G, Cavaliere F. Normal values of

exhaled carbon monoxide in healthy subjects: comparison between two

methods of assessment. BMC Pulm Med. 2014;16(14):204. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2466-14-204 PMid:25515007 PMCid:PMC4275957

- Friedman

AJ, Cosby R, Boyko S, Hatton-Bauer J, Turnbull G. Effective teaching

strategies and methods of delivery for patient education: a systematic

review and practice guideline recommendations. J Cancer Educ. 2011;

26(1):12-21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-010-0183-x PMid:21161465

- Bennett

S, Pigott A, Beller EM, Haines T, Meredith P, Delaney C. Educational

interventions for the management of cancer-related fatigue in adults.

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016;11: Art. No.: CD008144. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008144.pub2 PMCid:PMC6464148

- Fawzy

FI, Fawzy NW, Hyun CS, Elashoff R, Guthrie D, Fahey J, Morton DL.

Malignant melanoma: Effects of an early structural psychiatric

intervention, coping and affective state on recurrence and survival 6

years later. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1993;50:681-689. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820210015002 PMid:8357293

- Donker

T, Griffiths KM, Cuijpers P, Christensen H. Psychoeducation for

depression, anxiety and psychological distress: a meta-analysis. BMC

Medicine. 2009;7:79. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-7-79 PMid:20015347 PMCid:PMC2805686

- Pidala

J, Anasetti C, Jim H. Health-related quality of life following

haematopoietic cell transplantation: patient education, evaluation and

intervention. British Journal of Haematology. 2009;148:373-385. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07992.x PMid:19919651 PMCid:PMC2810350

- Kirsch,

M., Crombez, P., Calza, S., Eeltink, C. & Johansson E. (2012).

Patient information in stem cell transplantation from the perspective

of health care professionals: A survey from the Nurses Group of the

European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Bone Marrow

Transplantation 47, 1131-1133. https://doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2011.223 PMid:22139070

- Marques

ADCB, Szczepanik AP, Machado CAM, Santos PND, Guimarães PRB, Kalinke

LP. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and quality of life during

the first year of treatment. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2018; 25(26):e3065.

https://doi.org/10.1590/1518-8345.2474.3065 PMid:30379249 PMCid:PMC6206822

- Grulke

N, Albani C, BailerH. Quality of life in patients before and after

haematopoietic stem cell transplantation measured with the European

Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of

Life Core Questionnaire QLQ-C30. Bone Marrow Transplantation.

2012;47:473-482. https://doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2011.107 PMid:21602898

[TOP]