Naveen Gupta1, Manoranjan Mahapatra2, Tulika Seth2, Seema Tyagi2, Sudha Sazawal2 and Renu Saxena2.

1 Department of Medical Oncology, Mahatma Gandhi Medical College and Hospital, Jaipur, India

2 Department of Hematology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India.

Correspondence to:

Manoranjan Mahapatra, Professor & Head. Department of Hematology,

All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India. E-mail:

mrmahapatra@hotmail.com

Published: January 1, 2021

Received: August 7, 2020

Accepted: December 7, 2020

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2021, 13(1): e2021004 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2021.004

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Introduction:

Outcomes in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) have vastly improved after

introducing tyrosine kinase inhibitors. However, patients in low and

middle-income countries (LMICs) face many challenges due to social and

financial barriers.

Objective:

This study was conducted to understand socio-economic hindrances,

knowledge-attitudes-practices, and assessing nonadherence to treatment

in chronic phase CML patients taking imatinib.

Materials and Methods:

Patients of chronic phase CML, aged 15 and above, taking imatinib for

six months or more were included in the study. A questionnaire (in the

Hindi language) was administered, inquiring about the nature of the

disease and its treatment, how imatinib was obtained, drug-taking

behavior, and the treatment's economic and social burden. Nonadherence

was assessed by enquiring patients for missed doses since the last

hospital visit and for any treatment interruptions of ≥7 days during

the entire course of treatment (TIs).

Results:

Four hundred patients were enrolled (median age 37 years, median

duration on imatinib 63 months). Patients hailed from 16 different

Indian states, and 29.75% had to travel more than 500 kilometers for

their hospital visit. Scheduled hospital visits were missed by 14.75%.

A third of the patients were unaware of the lifelong treatment

duration, and 41.75% were unaware of the risks of discontinuing

treatment. Treatment was financed by three different means- 61.75%

received imatinib via the Glivec International Patient Assistance

Program (GIPAP), 14.25% through a cost-reimbursement program, and 24%

self-paying. 52.75% of patients felt financially burdened due to

the cost of drugs (self-paying patients), cost of investigations, the

expenditure of the commute and stay for the hospital visit, and loss of

working days due to hospital visits. 41.25% of patients reported missed

doses in the last three months, and 9% reported missing >10% doses.

16.5% of patients reported TIs. Nonadherence>10% and TIs were

significantly higher in self-paying patients (15.6% and 25%

respectively).

Conclusion:

We observed that patient awareness about the disease was suboptimal.

Patients felt inconvenienced and financially burdened by the treatment.

Nonadherence and treatment interruptions were observed in 41.25% and

16.5%, respectively. These issues were prevalent in self-paying

patients.

|

Introduction

The

long-term prognosis of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) underwent a

revolutionary change since the introduction of tyrosine kinase

inhibitors (TKIs). These agents have altered CML's natural history and

changed it from a fatal disease into a chronic disease with lifelong

treatment. Thousands of CML patients across the globe are currently

taking one of the TKIs. However, treating CML in low and middle-income

countries (LMICs) is still challenging owing to issues with patient

awareness, delayed diagnosis, and poor access to treatment. The current

study was conducted to understand knowledge-attitudes-practices of

patients of CML who are taking imatinib.

Study Methodology

This study was a single-center cross-sectional observational study conducted from 1st May 2017 to 31st

July 2018 at the Hematology clinic of a public sector tertiary hospital

in North India. Consecutive patients of chronic phase CML, aged 15

and above, who had been taking imatinib for six months or more, were

enrolled in the study. Patients in accelerated phase or blast phase and

those who were taking treatment other than imatinib were excluded.

Prior approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee was obtained.

All procedures followed were in accordance with the responsible

committee's ethical standards on human experimentation (institutional

and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in

2008. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being

included in the study.

Clinical history and examination

findings, along with demographic data and treatment procedures, were

recorded. The investigator administered a questionnaire (in the Hindi

language); wherein patients were asked about their perceptions of the

nature of the disease and its treatment, how imatinib was obtained,

drug-taking behavior, the economic and social burden of the treatment.

The patient reported nonadherence was recorded by enquiring the

percentage of missed doses since the last hospital visit and episodes

of treatment interruptions (TIs) of ≥7 days (at any point during

treatment).

Categorical variables were presented in number and

percentage (%), and continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD

and median. The normality of data was tested by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov

test. If the normality was rejected, then the non parametric test was

used. Quantitative variables were compared using the Kruskal Wallis

test for more than two groups. Qualitative variables were correlated

using the Chi-Square test. A p-value of <0.05 was considered

statistically significant. The data was entered in MS EXCEL

spreadsheet, and analysis was done using Statistical Package for Social

Sciences (SPSS) version 21.0.

Results

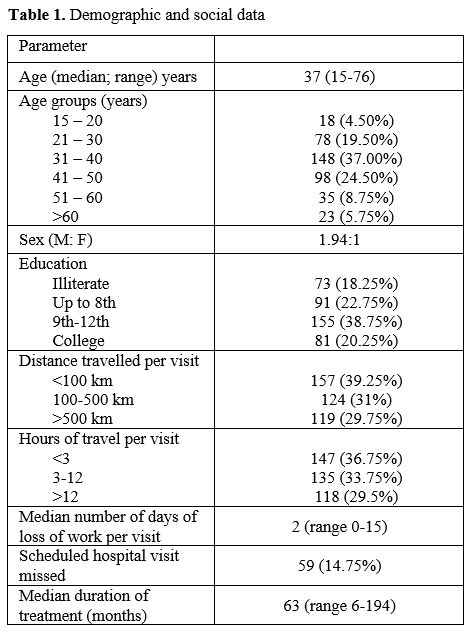

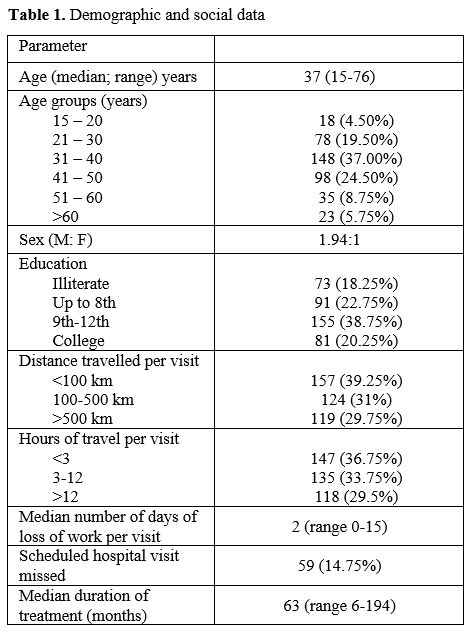

A total of 400 patients were enrolled. Demographic data is presented in Table 1.

The median age of the study group was 37 years, with a higher number of

male patients. The median duration on imatinib was 63 months. The study

group comprised patients from varied educational backgrounds, and

18.25% of the patients were illiterate. Patients hailed from 16

different states, with the largest numbers hailing from Uttar Pradesh,

Delhi, Haryana, and Bihar. Roughly one-third of the patients had to

travel more than 500 kilometers (each side) for their hospital visit

with a travel duration of >12 hours each side. Patients lost a

median of 2 workdays for each hospital visit. Scheduled hospital

visits were missed by 14.75% of patients.

|

Table

1. Demographic and social data .

|

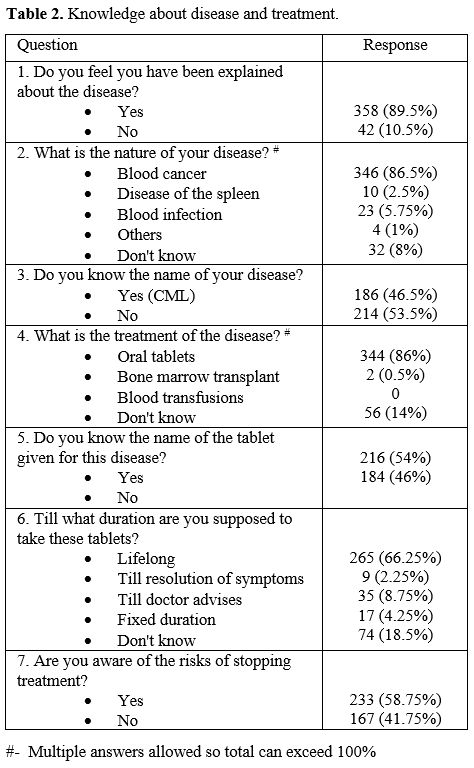

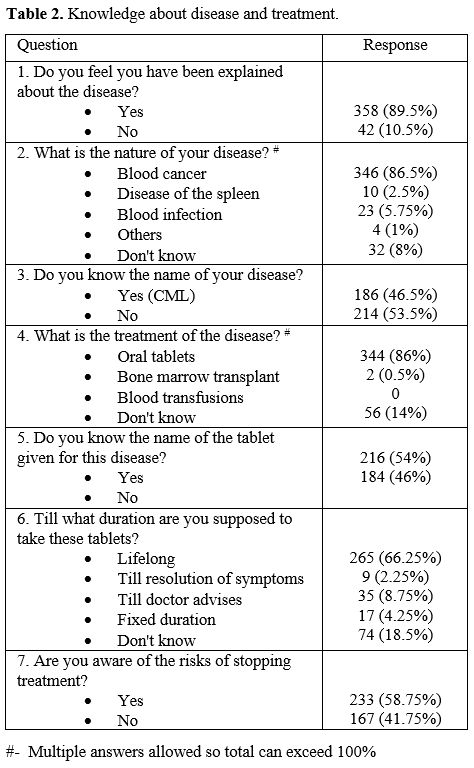

Patient awareness about the disease and treatment is described in Table 2.

The disease's nature was thought to be a "blood infection" by 23

patients (5.75%). A third of the patients were unaware of the lifelong

nature of the treatment. One hundred sixty-seven patients (41.75%) were

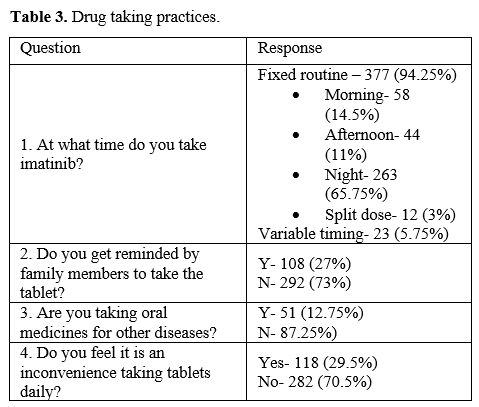

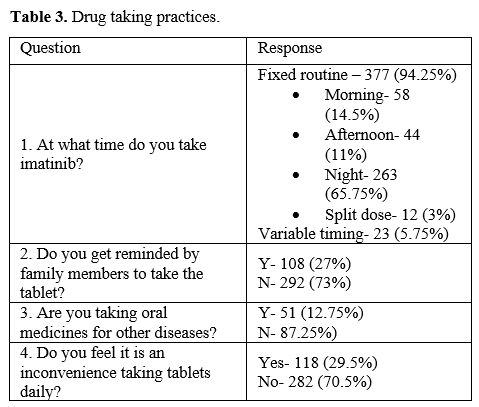

unaware of the risks of interrupting treatment. Drug-taking practices

are mentioned in Table 3. A

fixed routine for taking the drug was followed by 94.25% of the

patients, and nearly two-thirds preferred to take the drug at bedtime.

27% of the patients relied on reminders from family members to take the

drug every day. One hundred eighteen (29.5%) patients felt

inconvenienced by the treatment, and that was due to a combination of

adverse drug effects, treatment financial burden and to the need

for regular lifelong follow-up and treatment.

|

Table 2. Knowledge about disease and treatment. |

|

Table 3. Drug taking practices. |

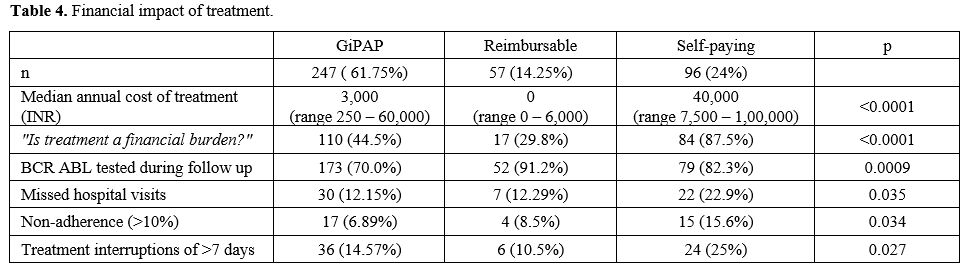

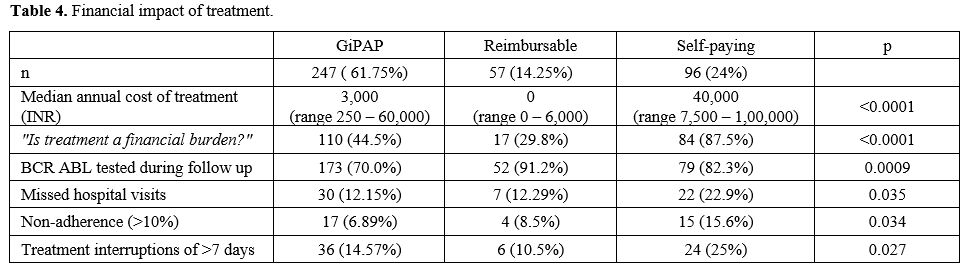

Imatinib was obtained through three different means (Table 4).

The majority (61.75%) obtained imatinib under the Glivec International

Patient Assistance Program (GIPAP). This group of patients received

imatinib free of cost from a designated GIPAP center in Delhi. They had

to bear the cost of investigations by themselves. The second group

(14.25%) of patients obtained imatinib through a cost-reimbursement

program which covered all treatment-related expenses. The third

group (24%) were self-paying patients who had to bear the entire

treatment cost themselves. The GIPAP group received Glivec, and the

other two groups of patients received generic imatinib. The median

annual treatment related expenditure was highest in the self-paying

group of patients, followed by the GIPAP group. The majority of

self-paying patients felt that the treatment was a significant

financial burden. 44.4% of patients in the GIPAP group also felt the

treatment was a financial burden due to the cost of investigations, the

expenditure of the commute for the visit, and loss of employment due to

hospital visits. Monitoring BCR-ABL IS by quantitative PCR (at any

point during follow-up) was done by 76% of patients. Among the three

groups, the GIPAP group had the maximum number of patients (30%) who

had not tested even once during follow-up.

|

Table 4. Financial impact of treatment.

|

One

hundred sixty-five patients (41.25%) reported missing a dose of

imatinib since the last hospital visit. The frequency of hospital

visits was once in 3 months. Thirty-six patients (9%) had missed more

than 10% of doses. Sixty-six patients (16.5%) reported treatment

interruptions of 7 days or more (at any time during treatment). The

self-paying patients had significantly higher nonadherence rates

(15.6%) and treatment interruptions (25%). (Table 4)

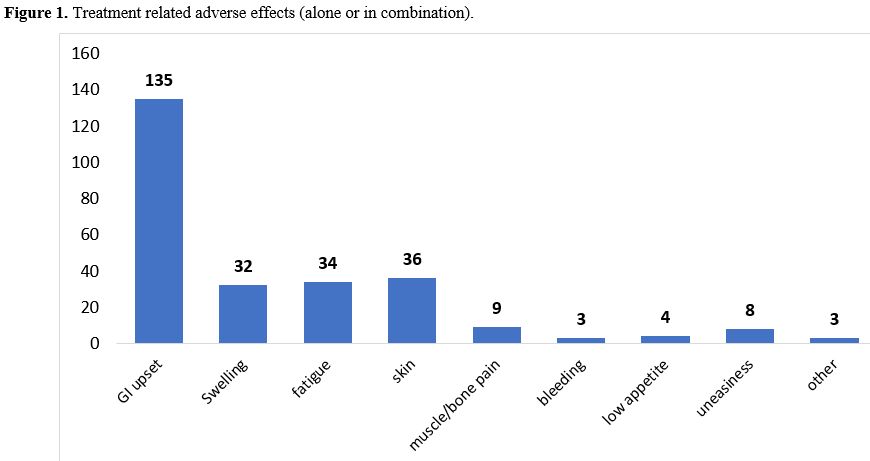

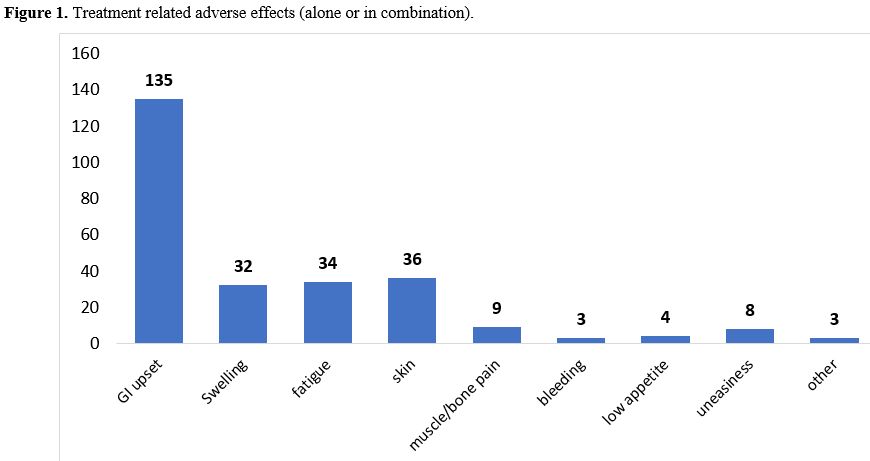

Most

common treatment-related adverse effects were gastrointestinal (nausea,

vomiting, and decreased appetite), followed by skin hypopigmentation

and fatigue. (Figure 1)

|

Figure 1. Treatment related adverse effects (alone or in combination).

|

Discussion

Majority

of the patients at public sector hospitals in LMICs hail from the lower

socioeconomic strata in whom education levels are low, as reflected by

a large number of illiterate patients in our study group. Our study

group's education status was similar to that observed in another Indian

study[1] and lower than those from Italy[2] and Brazil.[3] The

study population comprised patients of 16 states, and a large number of

them had to undertake lengthy travel for each hospital visit.

Hamerschlak et al. made similar observations in a study from Brazil.[4]

The lack of availability of hematology/oncology specialists in smaller

towns coupled with imatinib's unavailability at these centers leads to

aggregation of patients at tertiary hospitals in metro cities. The long

duration of travel leads to loss of work, and the cost of travel and

accommodation further adds to treatment-related expenditure and leads

to patient dissatisfaction. The costly and

cumbersome nature of hospital visits also leads to the patient missing

their scheduled hospital visits.

Patient awareness regarding disease and treatment has been suboptimal in studies from India[1] and Brazil,[4] whereas it was much better in studies from Europe.[2,5]

We observed low patient awareness regarding the nature of the disease

and treatment, particularly regarding treatment duration. This poor

information is a peculiar challenge faced during the treatment of CML

in low and middle-income nations, particularly in the public sector,

where many patients belong to the lower socioeconomic strata and are

less educated. Patient awareness is a critical component in ensuring

optimum treatment as lack of adequate knowledge about the disease adds

to patient anxiety, hampers adherence to treatment, and creates a trust

deficit between the patient and the physician.[6]

These findings reiterate the need for focused and easy-to-understand

counseling at diagnosis and its repeated reinforcement during

subsequent visits.

Patients tend to adopt various practices to

make the daily intake of drugs regular and convenient. We observed that

most patients followed a regular routine, and many relied on reminders

from family members. Similar practices have been reported previously as

well.[2,7] Studies from India have reported a lower incidence of comorbid ailments[8] than what is observed in developed nations.[9] and that can be attributed to a younger CML patient population in India.

Many

of our patients reported that the treatment caused them inconvenience

due to a combination of various factors-adverse drug effects, the

financial burden of treatment, and the need for regular lifelong

follow-up and treatment. This vital issue can get these patients

demotivated and may induce them to discontinue treatment.

The

financial impact of cancer treatment is immense, and it remains one of

the most important issues that patients have to take into consideration

while going for treatment.[10] The GIPAP program,

launched in 2001, provides free of cost Glivec to thousands of patients

across the globe. It has been a boon for patients of CML in low-income

countries. The greatest beneficiaries of the program have been from

India.[11] New patients were being enrolled in the

program till 2016, and almost all CML patients at our center prior to

this got their drug through GIPAP. This group comprises the major bulk

of CML patients at our center and it is reflected in the study

population with 62% enrolled under GIPAP. We observed that treatment

led to a substantial financial burden in our study group. The median

annual treatment related expenditure was highest in the self-paying

patients, for whom the cost of imatinib made up the bulk of the

treatment expenditure. A large number of GIPAP patients also felt

financially burdened by the treatment accessories related to the cost

of investigations, travel and accommodation for the hospital visit, and

loss of employment. The expenses are comparatively lower than other

countries[10] but still substantial for a country with an average annual per capita income of INR 92,565.[12]

The

cost of BCR-ABL quantitative estimation by PCR is around INR

6,000-7,000. This is almost two times the cost of monthly generic

imatinib. The unaffordability of repeated BCR-ABL estimations is

reflected by the high number of patients who did not get even a single

estimation done in the follow-up. This tendency is true even in

developed countries, and regular disease assessment either by

cytogenetics or molecular methods is infrequently seen outside the

setting of clinical trials.[13,14]

Nonadherence to TKI therapy is a major hindrance to obtaining favorable long term outcomes in patients with CML.[15,16]

The nonadherence patient-reported is a less sensitive methodology for

assessing nonadherence as it may underestimate the actual prevalence.

Despite this, we observed that a large number of patients were

non-adherent to imatinib, and also that many patients reported lengthy

treatment interruptions. Previous studies from India have observed

nonadherence rates of 25% to 55%.[1,8,15]

The proportion of nonadherence >10% and TIs was significantly higher

in the self-paying patients, concerning the financial difficulties

faced by these patients.

Managing CML in low and middle-income

countries requires careful titration of the treatment according to the

patients' socioeconomic status. All avenues of financial support from

both government and non-government schemes must be pursued to ensure

uninterrupted treatment.[17] The excellent survival

rates of patients under the GIPAP program are a testament to the fact

that by improving accessibility to TKIs in LMICs, we can produce

results comparable to high-income countries.[18] The

availability of TKIs must be coupled with better penetrance of

hematology/oncology services to smaller towns and cities and an

emphasis on better patient education and treatment adherence.

Our

study has several limitations. Patients were assessed at only a single

time point without follow up. The disease's awareness would depend upon

the initial patient counselling and education that might not be uniform

for all patients. The patient-reported nonadherence was assessed over a

3-month duration, which is a less sensitive method and underestimates

the actual nonadherence.

Conclusions

This

study highlights the major challenges encountered in TKI-based

treatment of CML in low and middle-income countries. Inadequate patient

education status contributes to suboptimal awareness about disease and

treatment. Lack of hematology/oncology services in most parts of the

country, costs of drugs and investigations pose a significant financial

burden on the patients. Nonadherence (>10% of doses) and treatment

interruptions were observed in 9% and 16.5% of patients respectively.

These were significantly higher in self-paying patients.

References

- Unnikrishnan R, Veeraiah S, Mani S, Rajendranath R,

Rajaraman S, Vidhubala Elangovan GS, et al. Comprehensive Evaluation of

Adherence to Therapy, Its Associations, and Its Implications in

Patients With Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Receiving Imatinib. Clin

Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2016 Jun;16(6):366-371.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clml.2016.02.040 PMid:27052853

- Breccia

M, Efficace F, Sica S, Abruzzese E, Cedrone M, Turri D, et al.

adherence and future discontinuation of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in

chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia. A patient-based survey on 1133

patients. Leukemia Research. 2015 1st October;39(10):1055-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leukres.2015.07.004 PMid:26282944

- de

Almeida MH, Pagnano KBB, Vigorito AC, Lorand-Metze I, de Souza CA.

Adherence to tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy for chronic myeloid

leukemia: a Brazilian single-center cohort. Acta Haematol.

2013;130(1):16-22. https://doi.org/10.1159/000345722 PMid:23363706

- Hamerschlak

N, Souza C de, Cornacchioni AL, Pasquini R, Tabak D, Spector N, et al.

Patients' perceptions about diagnosis and treatment of chronic myeloid

leukemia: a cross-sectional study among Brazilian patients. Sao Paulo

Med J. 2015 Dec;133(6):471-9. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-3180.2014.0001306 PMid:25388686

- Noens

L, van Lierde M-A, De Bock R, Verhoef G, Zachée P, Berneman Z, et al.

Prevalence, determinants, and outcomes of nonadherence to imatinib

therapy in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia: the ADAGIO study.

Blood. 2009 28th May;113(22):5401-11. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2008-12-196543 PMid:19349618

- Ruddy

K, Mayer E, Partridge A. Patient adherence and persistence with oral

anticancer treatment. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2009 1st

January;59(1):56-66. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.20004 PMid:19147869

- Eliasson

L, Clifford S, Barber N, Marin D. Exploring chronic myeloid leukemia

patients' reasons for not adhering to the oral anticancer drug imatinib

as prescribed. Leuk Res. 2011 May;35(5):626-30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leukres.2010.10.017 PMid:21095002

- Kapoor

J, Agrawal N, Ahmed R, Sharma SK, Gupta A, Bhurani D. Factors

influencing adherence to imatinib in Indian chronic myeloid leukemia

patients: a cross-sectional study. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis.

2015;7(1):e2015013. https://doi.org/10.4084/mjhid.2015.013 PMid:25745540 PMCid:PMC4344173

- Efficace

F, Baccarani M, Rosti G, Cottone F, Castagnetti F, Breccia M, et al.

Investigating factors associated with adherence behaviour in patients

with chronic myeloid leukemia: an observational patient-centered

outcome study. Br J Cancer. 2012 4th September;107(6):904-9. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.348 PMid:22871884 PMCid:PMC3464760

- Jiang

Q, Yu L, Gale RP. Patients' and hematologists' concerns regarding

tyrosine kinase-inhibitor therapy in chronic myeloid leukemia. J Cancer

Res Clin Oncol. 2018 Apr;144(4):735-41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-018-2594-8 PMid:29380058

- Garcia-Gonzalez

P, Boultbee P, Epstein D. Novel Humanitarian Aid Program: The Glivec

International Patient Assistance Program-Lessons Learned From Providing

Access to Breakthrough Targeted Oncology Treatment in Low- and

Middle-Income Countries. J Glob Oncol. 2015 23rd September;1(1):37-45. https://doi.org/10.1200/JGO.2015.000570 PMid:28804770 PMCid:PMC5551649

- Mospi.gov.in.

(2020). Press note on provisional estimates of annual national income,

2018-19 and quarterly estimates of gross domestic product for the

fourth quarter (q4) of 2018-19. [online] Available at: http://www.mospi.gov.in/sites/default/files/press_release/Press%20Note%20PE%202018-19-31.5.2019-Final.pdf

- Goldberg

SL. Monitoring Chronic Myeloid Leukemia in the Real World: Gaps and

Opportunities. Clinical Lymphoma Myeloma and Leukemia. 2015 1st

December;15(12):711-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clml.2015.08.088 PMid:26433907

- Geelen

IGP, Thielen N, Janssen JJWM, Hoogendoorn M, Roosma TJA, Willemsen SP,

et al. Treatment outcome in a population-based, 'real-world' cohort of

patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2017

Nov;102(11):1842-9. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2017.174953 PMid:28860339 PMCid:PMC5664388

- Ganesan

P, Sagar TG, Dubashi B, Rajendranath R, Kannan K, Cyriac S, et al.

Nonadherence to imatinib adversely affects event free survival in

chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia. Am J Hematol. 2011

Jun;86(6):471-4. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.22019 PMid:21538468

- Ibrahim

AR, Eliasson L, Apperley JF, Milojkovic D, Bua M, Szydlo R, et al. Poor

adherence is the main reason for loss of CCyR and imatinib failure for

chronic myeloid leukemia patients on long-term therapy. Blood. 2011 7th

April;117(14):3733- 6. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2010-10-309807 PMid:21346253 PMCid:PMC6143152

- Malhotra

H, Radich J, Garcia-Gonzalez P. Meeting the needs of CML patients in

resource-poor countries. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2019

6th December;2019(1):433-42. https://doi.org/10.1182/hematology.2019000050 PMid:31808889 PMCid:PMC6913442

- Umeh

CA, Garcia-Gonzalez P, Tremblay D, Laing R. The survival of patients

enrolled in a global direct-to-patient cancer medicine donation

program: The Glivec International Patient Assistance Program (GIPAP).

EClinicalMedicine. 2020 Feb;19:100257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100257 PMid:32140674 PMCid:PMC7046500

[TOP]