Stergios

Intzes, Marianthi

Symeonidou, Konstantinos Zagoridis, Zoe Bezirgianidou, Georgios

Vrachiolias, Athina Spanoudaki and Emmanouil Spanoudakis.

Democritus

University of Thrace, Medical School, Department of Hematology.

Alexandroupolis, Greece.

Correspondence to: Emmanouil Spanoudakis, Assistant Professor

of

Hematology. Democritus University of Thrace, Medical School.

Alexandroupolis, Greece, Area of Dragana, PC 68100. E-mail:

espanoud@med.duth.gr

Published: January 1, 2021

Received: August 17, 2020

Accepted: December 7, 2020

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2021, 13(1): e2021006 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2021.006

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Background:

Socioeconomic status (SES) is reflecting differences in

sociodemographic factors affecting cancer survivorship. Deprived, low

SES populations have a higher prevalence of multiple myeloma and worst

survival, a condition which widens over time.

Methods:

We performed a meta-analysis of 16 studies (registries and cohorts)

reporting myeloma patients' survival data according to SES. Ten studies

reported Hazzard Ratio (H.R.) (95 % CI), and 16 studies reported p

values. We combined the H.R. from 10 studies, and by using the

Mosteller-Bush formula, we performed a synthesis of p values according

to the area of the globe.

Results:

Combination of H.R. from 10 studies including 85198 myeloma patients

weighted to sample size of each study and adopting the hypothesis of

random effect returned a combined H.R.: 1,26 (1,13-1,31) in favor of

high SES patients.

USA: Synthesis of p values coming from 6

studies (n=89807 pts) by using the Mosteller and Bush formula extracted

a p-value of <0.0001 favoring high SES patients.

Oceania:

Synthesis of p values in two cohorts from Australia and New Zealand (n=

10196 pts) returned a p-value of 0,022 favoring high SES patients.

Europe:

The synthesis of p values from the U.K. and Greece studies (n=18533

pts) returned a p-value of <0,0001 favoring high SES patients.

Asia: Synthesis of 2 studies from Asia (n=915 pts) returned a p-value

of <0,0001 favoring high SES patients.

Conclusions:

Across the globe and widening over decades, the socioeconomic status

remains a gap for equality in myeloma care.

|

Introduction

Overall

Survival (O.S.) of multiple myeloma (MM) patients has improved over the

last decades, with 50% of patients surviving beyond five years after

diagnosis.[1] Autologous

transplantation (ASCT) is still the most

effective anti-myeloma therapy.[2]

However, the introduction of

proteasome inhibitors (bortezomib, carfilzomib, ixazomib), new IMiDs

(lenalidomide, pomalidomide), and anti-CD38 and anti-SLAM monoclonal

antibodies improved survival for both newly diagnosed myeloma (NDMM)

and refractory/relapsed myeloma (RRMM) patients.[3]

Despite

all

this progress, disparities in myeloma care are globally noted, with not

all myeloma patients finally achieving the expected survival benefit. A

primary reason for inequalities in myeloma care is differences in

social resources. The socioeconomic status (SES) is an index calculated

based on education, social support, and income but, actually, is a

surrogate marker reflecting differences in factors like ethnicity or

race, availability of new treatment options, access to health system

facilities, disparities in insurance status/ refurbishment of

anti-myeloma drugs, occupation and place of living (rural or urban vs.

metropolitan).[4] Racial or ethnic

differences in myeloma reflect

differences in factors that interfere with the SES status and disease

biology during all stages of myeloma evolution (from monoclonal

gammopathy to symptomatic myeloma).[5]

Ethnicity/Racial Disparities in

Myeloma Care

The

incidence of myeloma in California is higher for African-Americans

(A.A.) ancestry compared to other races, and most patients are affected

in earlier decades of their lives. Interestingly, A.A. with the highest

SES has 50% more likelihood of being diagnosed with MM.[6]

Although A.A. has a higher incidence of MGUS transformation rates to

symptomatic myeloma is the same across all ethnic subgroups with lower

progression rates for patients from Japan and Mexico.[5]

Disease

characteristics like myeloma-related events or high-risk features are

different across racial/ethnic subgroups. African American patients are

thought to have a lower incidence of specific high-risk cytogenetics

abnormalities (deletion of 17p) but higher rates of t(11;14) and 1q

amp.[7] A mutational study recently

showed that A.A.

myeloma patients had a lower prevalence of the high risk p53 mutation,

while across all ethnic groups, NRAS and KRAS are the most frequently

occurred mutations.[8] Furthermore,

the incidence of

myeloma-related end-organ damage (e.g., need for kidney dialysis),

factors that can delay therapy or put limitations in drug choice, has

been reported with varying incidence according to racial/ethnic

subgroups, affecting thus disease outcome and prognosis.[9]

A.A.

patients with MM, examined on the treatment offered, were less likely

to undergo ASCT and be treated with bortezomib, leading to a potential

association with the worst prognosis.[10]

The

age-adjusted odds of receiving ASCT for MM were significantly higher

for white than for A.A. patients (odds ratio, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.64–1.86;

p=0,01)[11,12] although a recent

study from a single

center in Minnesota reported that SES was in less than 2% of cases a

barrier in order patients to be referred for ASCT.[13]

Another single-center study reported that A.A. patients have a time

since referral to ASCT longer than Whites.[14]

Data from SEER-Medicare data from 2003-2017 shows that ASCT use rates

during first-year increases for A.As.[15]

Notably, African American patients compared to white Americans after

receiving autologous transplant have no difference in disease outcome

(PFS or O.S.), meaning that ASCT can overcome biological differences

among racial subgroups or that equality of treatment overcomes all

racial disparities.[16,17,18] A

recent study by

Munshi et al. conducted on army veterans showed that O.S. disparities

across different races are lost and possibly reversed when all patients

have the same insurance and access to health system providers.[19]

Similarly,

access to new agents is not equal across ethnic/racial subgroups in

health systems where these agents are approved. During the first year

after MM diagnosis, White and African American patients had higher

bortezomib-only usage, but A.A. had lower lenalidomide usage, whereas

Hispanic and Asian patients had higher immunomodulatory drug-only

utilization.[10] Furthermore, a

substantial increase

was seen over the years for both lenalidomide and bortezomib use for

all subgroups except Hispanic patients, and a notable increase in

bortezomib use was noted for all subgroups except Asian patients.[20]

Notably, even today use of novel agents is more distanced from

diagnosis for patients with A.A. and Hispanic origin (5,2 and 4,6

months, respectively) compared to Whites (2,7 months).[15]

Novel Anti-Myeloma Agents and

Disparities in Myeloma Care According to Race/Ethnicity

Another

reason for disparities in myeloma care is participation in clinical

trials testing novel anti-myeloma agents. Patients with MM of Asian or

Hispanic origin are similarly underrepresented in clinical trials

testing new agents in myeloma care. Apart from this, A.A. cancer

patients participating in 35 SWOG clinical trials showed that

early-stage breast and prostate cancer patients of A.A. origin had a

worse outcome; however, an equal survival was noted for myeloma

patients.[21] Overall, in

myeloma's nine clinical studies till 2011, only 18% of patients were

non-Whites and Hispanics.[22,23]

Survival data from these studies show equal survival among ethnic

groups when receiving treatment on the study protocol. A recent

meta-analysis of patients included five clinical trials of myeloma

shows increasing participation of minorities over decades, but still,

Whites are the racial group most often participated in them.[23]

The VISTA study included white race in more than 99% of participants

and other trials FIRST, MMY3002, etc. Whites are 75-88% of

participants. In this meta-analysis, survival rates, according to race,

showed equal probabilities of survival in patients of Asian Pacific

ancestry compared to Whites if they received the new anti-myeloma

drugs.[24] Dilemmas about

different effectiveness of

novel anti-myeloma agents, especially monoclonal antibodies, in disease

control due to immunological haplotypes were not proved evidence-based

since, in a small series of 82 patients treated with either elotuzumab

or daratumumab response rates, duration of response and adverse events

were similar across ethnic groups.[25]

|

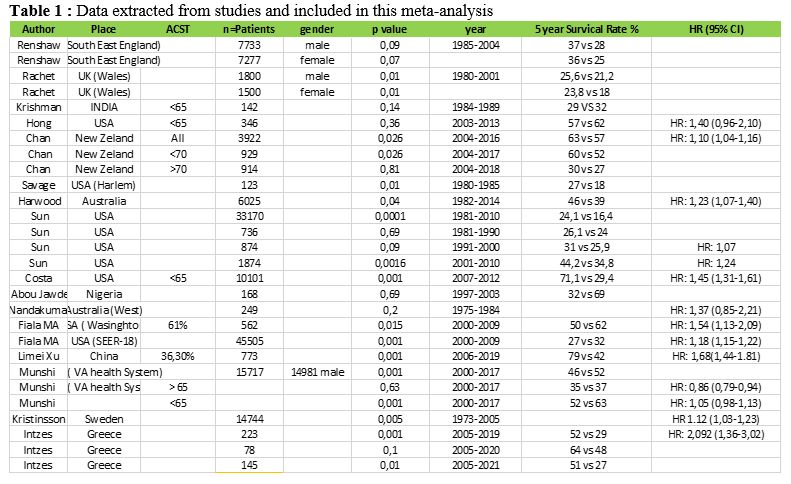

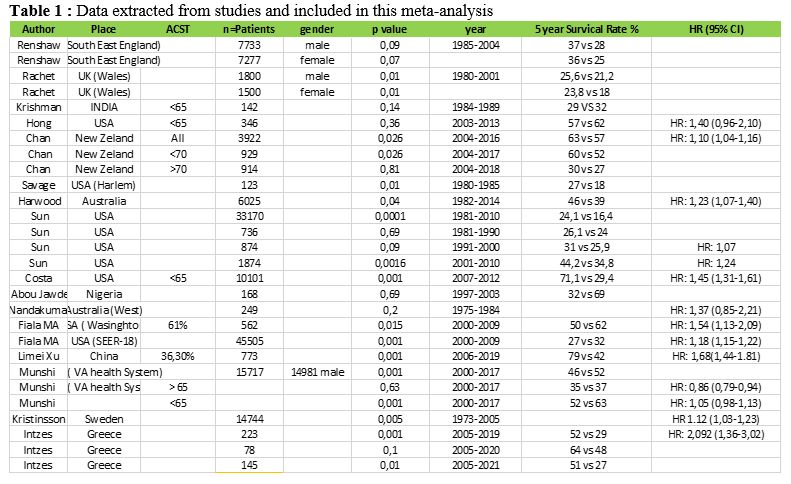

Table

1. Data extracted from studies and included in this meta-analysis.

|

Single-center Experience on Myeloma

Care in the Muslim Minority of Thrace, Greece

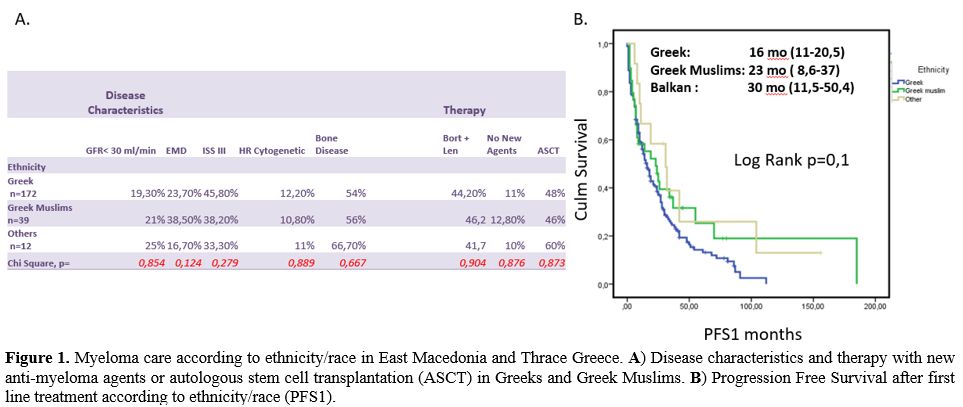

In

our single-center cohort of 223 MM patients from East Macedonia and

Thrace in Greece, 172 patients were of Greek origin, 39 were of Greek

Muslims, and 12 of Balkan origin. The end-organ damage (end-stage renal

failure, severe bone disease) were not different across racial

subgroups (Figure 1A).

The

presence of Extra Medullary Disease (EMD) prevailed in a higher

percentage in Greek Muslims, but other high risk features like ISS

stage III and high risk cytogenetics were equally distributed among

racial subgroups. Autologous SCT was offered in the same percentage of

transplant-eligible patients (48% vs. 46%, p=0,873), and the exposure

to both lenalidomide and bortezomib (at least two complete cycles from

each agent) was administered at the same percentage of patients (Figure 1A).

Survival data shows equal median O.S. across racial subgroups, but

myeloma patients of Greek Muslim origin had longer PFS after first-line

anti-myeloma therapy, but no statistical significance was reached (Log

Rank p=0,1, Figure 1B).[26]

|

Figure

1. Myeloma care according to ethnicity/race in East Macedonia and

Thrace Greece. A) Disease

characteristics and therapy with new anti-myeloma agents or autologous

stem cell transplantation (ASCT) in Greeks and Greek Muslims. B) Progression Free

Survival after first line treatment according to ethnicity/race (PFS1).

|

Access to Medical Centers and Availability

of Best Anti-Myeloma Care

Overall,

cancer patients in the USA do not have the same probabilities of

receiving care and therapy for their disease in NCI institutes, so the

different outcomes in all cancers. Access to National Cancer Institute

(NCI) and National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) increased

myeloma-related survival after 1996 in places with more than 2 NCI

centers or more than 1 NCCN center and only for White patients.

Accordingly, for ASCT, the best available anti-myeloma therapy with

decreasing mortality rates through decades, disparities exist according

to patients' insurance status and hospitals' volume where ASCT took

place.[27] Low volume hospitals

(<10 ASCT per

year) had a crude mortality rate of 3,86% compared to 0,80% for high

volume hospitals, and public hospitals had a crude mortality rate of

2,86% vs. 0,78% hospitals caring for patients with other insurance

coverage. Facility volume is generally related to myeloma survival.

National Cancer database includes 94.777 MM patients and 1333 medical

centers, after multivariable analysis, showed that facility volume was

independently associated with all-cause mortality for private

hospitals. The unadjusted median overall survival by facility volume

was 26.9 months for low volume facilities vs. 49.1 months for high

volume facilities.[28]

Outside the USA in 15

Latin American countries, the FISH analysis was available in 67% of

patients, MRI in 44%, and PET/CT was offered in 66,7% of patients.

Treatment availability queries showed that ASCT was available in 11/13

countries, bortezomib, and lenalidomide in more than 90% of reported

physicians, and pomalidomide, carfilzomib, and daratumumab is

accessible in around 60% of physicians participating in this study.

Maintenance therapy was prescribed in almost all indicated patients.

However, there were significant differences in access to tests and

treatments for multiple myeloma between public and private systems.

Although patients can be referred to the private or public center for

anti-myeloma care, that does not significantly impact patients'

survival when the same protocols were utilized. All physicians reported

having access to thalidomide and bortezomib. Autologous stem cell

transplant (ASCT) is available in most countries (11/13). Lenalidomide

is commercially available in 97.9% (96), melphalan in 92.7% (94),

daratumumab in 68% (65), pomalidomide in 67% (57), carfilzomib in 60%

(57), and ixazomib in 18%. Nevertheless, the commercial availability of

these drugs does not mean patients have access to them, as

reimbursement issues and local health policies often do not provide

them due to their high cost.[29]

Socioeconomic Status and Cancer

Survivorship

SES

has been linked with survival in a variety of cancers. Afshar et al.,

in a study from Australia reporting survival data in all cancer

patients diagnosed between 2001-2015, found that patients from the most

deprived for social sources areas had worst cancer survivorship with

patients with lung, colorectal, breast, prostate cancer, and melanoma

to have the higher survival gap according to SES.[30]

A recent analysis of SEER registry data, including 327078 cancer

patients from the USA, showed increased mortality for low SES patients

than high SES patients across all races and ethnicities. In high SES

patients, Whites had better survival compared to other high SES

patients from other races; a difference widened in patients suffering

from breast colorectal or prostate cancer.[31]

Socioeconomic Status and

Hematological Malignancies

Deprived

socioeconomic status has been linked with poor survival and a wide

variety of myeloid[32] and

lymphoid[33,34]

hematological malignancies. Children and young adolescents with acute

myeloid (AML) and lymphoid leukemia (ALL) enjoy improvement over

decades of survival. Racial disparities are not that sharp now a days,

especially for ALL patients, and allogeneic transplants are equally

offered across all races, but there is still a gap in donor

availability in patients of A.A. origin.[35]

In

Diffuse Large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) patients, conflicting data about

SES's effect on survival exists. In the USA, DLBCL patients with

no-insurance or Medicaid insurance had inferior survival compared to

non-Medicaid insurance.[36]

Studies show that

patients from urban/rural areas compared to metropolitan areas had the

worst survival due to a multifactorial etiology.[37]

Delay in diagnosis, low SES, deprivation of financial resources, and,

most importantly, fewer probabilities of receiving care in a high

volume experienced in the lymphoma medical center are the main reasons

for low SES patients' worst outcome. A recent study from the USA shows

that low SES patients do not receive chemo-immunotherapy at the same

rate, and when therapy is equal, survival rates are not affected by

SES, at least for older patients above the age of 65. Hodgkin disease

survival in young adults is not different across racial barriers, but

Hodgkin disease incidence is strongly related to living in high SES

affluent areas.[38] In Follicular

lymphoma, a disease

with a chronic course with remissions and relapses, similarly to MM,

patients below 65 with the USA's worst insurance had a hazard ratio for

death 1,96 (H.R 1.96; 95% CI, 1.69-2.28).[39]

SES is related to diminish survival rate in mantle cell lymphoma

patients as well.[34]

Considering

the impact of SES on myeloma survival, many data exist in the

literature that supports SES as a prognostic survival factor globally

and across all decades.[40,41,42]

Some studies are relating to SES and the incidence of myeloma.

Socioeconomic Status and Incidence of

Multiple Myeloma

Incidence

of myeloma is highly variable among countries but is globally rising

through the decades, reaching 2,1 cases per 100.000 habitants per year.[43] The highest prevalence of myeloma

is met in Australia, North America, and Western Europe.[43]

Available data about the incidence of MM and SES are conflicting. In

population-based studies, MM and its preceded MGUS have been positively

related to high SES because of earlier diagnosis.[44]

Other studies are reporting a higher incidence of MM in low SES mostly

related to occupational hazard[45]

with farmers and industrial workers, especially after prolonged

exposure to pesticides or other industrial chemicals to be in danger.[46,47] Obesity, a strong risk factor

for MGUS development, is often seen in patients with low

sociodemographic characteristics.[48]

A population case-control study included 206 Black and 367 White MM

cases plus 2131 controls found out that low occupation-based SES was

significantly associated with an increased risk of MM.[49]

Socioeconomic Status and Myeloma

Survival

Plenty

of cohort studies reports data on the role of SES on myeloma survival

in the literature. In order to extract and analyze all available data,

we performed a meta-analysis of published studies.

Search Strategy and Statistical

Analysis

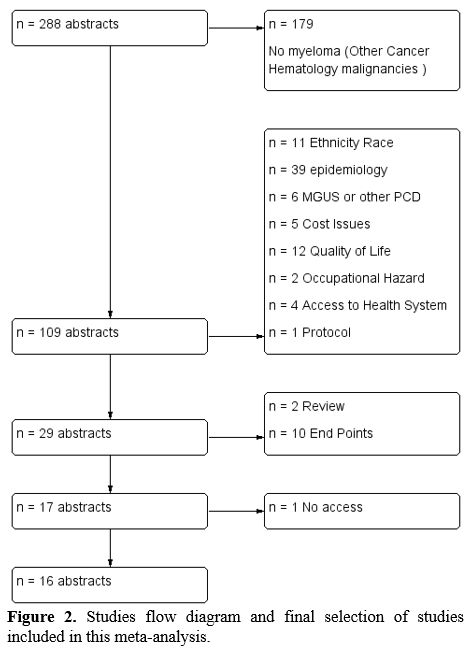

We

conducted a PubMed search using the following criteria; (myeloma OR

plasma cell dyscrasia) AND (socioeconomic status OR social index OR

SES), and 288 abstracts were returned. After reading abstracts, we

resulted in 29 studies. Three independent reviewers (ES, SI, MS) red

full-text articles and 16 studies full-filling our inclusion criteria

(reporting five ys survival rate in patients with High or Low SES) were

included in this meta-analysis of cohort studies. After selecting

studies, data were extracted, and we compared five ys O.S. in High SES

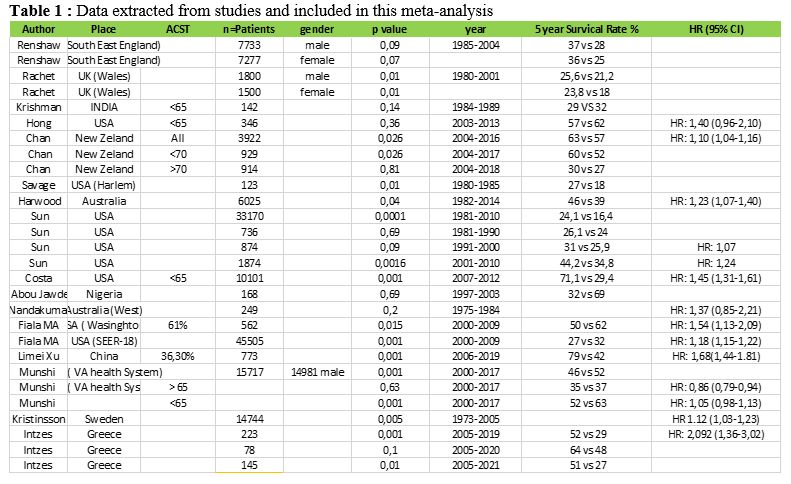

and Low SES myeloma patients (Studies Flow Diagram in Figure 2).

|

Figure

2. Studies flow diagram and final selection of studies included in this

meta-analysis.

|

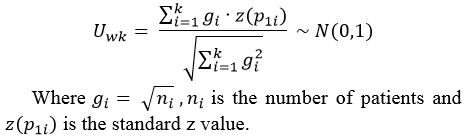

We

separated subgroups according to the geographical area of the study. To

synthesize data from different cohort studies, we used the Mosteller

and Bush formula, which is the generalization of the z-test. This

formula gives weight to each study concerning the number of patients.

Under the null hypothesis, the weighted sum still has a normal

distribution with mean 0 and variance equals the sum of the weights'

square. So we have the formula:

In

some studies (n=10), Hazzard Ratio (H.R.), and 95% confidence interval

for O.S. in High SES and Low SES myeloma patients were reported. By

using the RevMan software, a Cochrane tool, we performed a

meta-analysis of the reported H.R.

Results

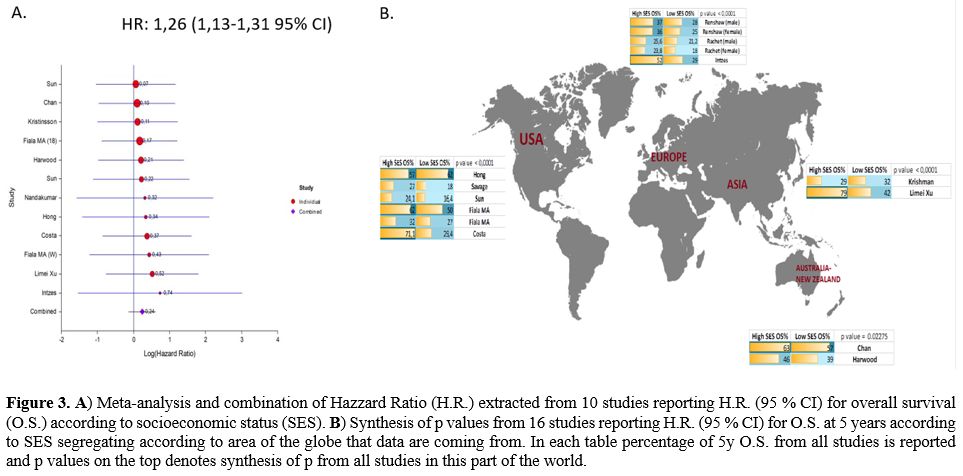

Combined from Eleven Studies Hazzard Ratio for Death in High SES and

Low SES Myeloma Patients

A

meta-analysis of 10 studies (two of them Sun et al., Fiala et al. gives

H.R. in two cohorts) that reported H.R. and 95% CI for survival

differences according to SES status of myeloma patients, weighted to

sample size of each study and to adopt the hypothesis of random effect

returned a combined H.R.: 1,26 (1,13-1,31). In this meta-analysis,

85198 myeloma patients were included demonstrating a better survival

probability for high SES patients by 1,26 times compared to low SES

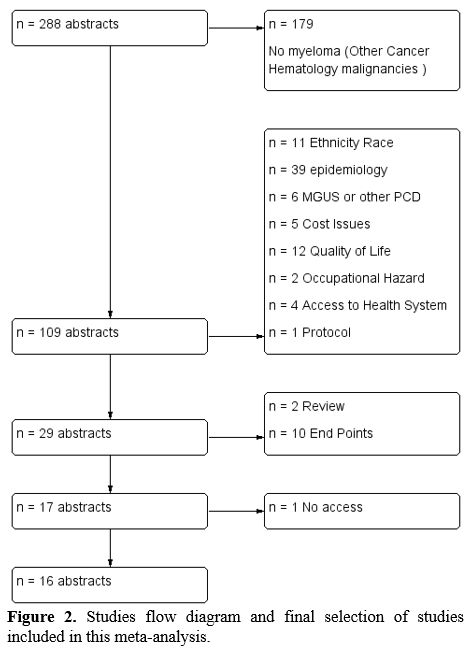

patients (Figure 3A).

|

Figure

3. A)

Meta-analysis and combination of Hazzard Ratio (H.R.) extracted from 10

studies reporting H.R. (95 % CI) for overall survival (O.S.) according

to socioeconomic status (SES). B)

Synthesis of p values from 16 studies reporting H.R. (95 % CI) for O.S.

at 5 years according to SES segregating according to area of the globe

that data are coming from. In each table percentage of 5y O.S. from all

studies is reported and p values on the top denotes synthesis of p from

all studies in this part of the world.

|

Socioeconomic Status and Disparities

in 5 Years Overall Survival of Myeloma Patients According to Geography

In

this meta-analysis, we conducted a synthesis of p values by using the

Mosteller and Bush formula and included 134363 myeloma patients. We

extracted data from studies, and we reported a 5-year O.S. rate in Low

and High SES patients. Two studies are reporting separately for women

and men (Renshaw and Rachet). We made a synthesis of p values from

studies in four geographic areas of the globe; USA included six studies

(Sun et al., Costa et al., Savage et al., Hong et al., Fiala cohort,

and SEER data), Australia and New Zeeland 3 studies (Chan et al.,

Harwood et al., Nandakumar et al.), Europe 3 studies (Renshaw et al.,

Rachet et al., Intzes eta al), Asia included two studies (Krismann et

al., Limei Xu et al.)

USA: Health System Disparities and

the Impact of SES on Myeloma Survival

In

the United States, there is no single national system of health

insurance. Health insurance is purchased in the private marketplace or

provided by the government to some groups. Private health insurance can

be purchased from commercial insurance companies or non – profit

insurers. About 84% of the population is covered by either public (26%)

or private (70%) health insurance. Approximately 61% of health

insurance coverage is employment-related.

The health care system

in the USA is characterized by broad economic inequalities. The life

expectancy of the wealthiest Americans now exceeds that of the poorest

by 10-15 years. Poor Americans have worse access to health care than do

wealthy Americans because many remain uninsured despite coverage

expansions since 2010 due to the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

Significantly, more than 37 million Americans do not have health

insurance, and 41 million more have inadequate access to care.

According

to SEER registry reporting data from over than 30.000 myeloma patients

diagnosed from 1981 to 2010 in the USA, gap on survival rates according

to SES has widened over time (affluent to deprived: 26,1%, 26,8% and

24,8% in the first decade, 31,2%, 28,1%, and 25,9% in the second decade

and 44,2%, 40,5%, and 34,8% in the third decade). The Kaplan–Meier

survival analyses confirmed the widening survival gaps among SES

groups, with p values of 0,0016 during the last decade when more

effective anti-myeloma treatments became available.[50]

This

decade's focus was made by Costa et al., reporting data from 10,161

cases of MM diagnosed before the age of 65 years from 2007 t0 2012 and

included in the SEER-18 registry. In the Cox proportional hazards

model, only marital status, insurance status, and county-level income

significantly influenced O.S. The cumulative effect of sociodemographic

factors associated with shorter survival in the multivariable analysis

was statistically significant (p<0,0001). The 4 years OS%

reported

71,1%, 63,2% 53,4% and 46,5% for patients with 0, 1, 2, 3 adverse

sociodemographic factors.[51]

Fiala et al.

reported retrospectively from five-hundred-sixty-two patients eligible

for analysis included in medical records from Washington University

School of Medicine.

High-SES patients were less likely to have

comorbidities at diagnosis than middle-SES and low-SES patients (58%

compared to 72% and 76%, p=0.007) and were more likely to have private

insurance at diagnosis. High-SES patients were more likely to undergo

ASCT than middle-SES and low-SES patients (72% compared to 59% and 52%,

respectively, p<0.001). In multivariate analysis of SES, age at

diagnosis, year of diagnosis, race, comorbidity score, ASCT

utilization, and insurance provider, all other variables except

insurance provider, were independently associated with survival.[41]

The

same group tested their patients' results in SEER-18 registry reporting

from patients recorded until November 2012. 45.505 MM patients were

identified for analysis. The median age at diagnosis was 69 years

(range 18–85+), and 18 percent were black. In a multivariate model, SES

was associated with O.S. [HR 1.18 (95% CI 1.15–1.22) for low-SES

relative to high-SES; HR 1.10 (95% CI 1.07–1.13) for middle-SES

relative to high-SES].[41]

Hong et al. reported

data from 354 transplant eligible patients from the USA, and they did

not observe any significant differences in O.S. or Progression-Free

Survival (PFS) and relapse rate based on recipient SES at ASCT in

univariate analyses or multivariable analysis after adjusting for

significant patient-, disease-, and transplantation-related variables.[52]

There

is also a small study from Harlem Hospital reporting from 1980 to 1985

and found out that low socioeconomic index resulted in a significantly

lower five-year O.S. rate (27 vs. 18%; p=0,01).[42]

We

performed the synthesis of p values coming from these six studies

(n=89807 pts) by using the Mosteller and Bush formula, and the

extracted p-value was <0.0001, meaning that in the USA, there is

a

statistically significant association between low SES and O.S. across

all age groups and decades (Figure

3B).

Australia: Health System Disparities

and the Impact of SES on Myeloma Survival

The

Australian health system involves multiple layers of responsibility and

funding provided by governments, individuals, and private health

insurers.

Primary care is mostly provided in the community by

general practitioners (GPs) who are generally self-employed. G.P.s also

operate as 'gatekeepers', referring patients to specialist medical

services where needed. The national public health insurance scheme

«Medicare» provides subsidies for most medical and diagnostic and some

other health services.

Public hospital treatment is free for

people but can be subject to long waiting times for elective surgery.

Private hospitals cater to patients who want a choice of doctor and

private ward accommodation. For private hospitals, Medicare pays 75

percent of the Medicare schedule fee, with the balance met by private

health insurance.

A range of free or low-cost public health

services, including immunization and mental health services, are

provided by community health facilities. Prescription medicines are

dispensed by private community pharmacists paid by the Australian

government (under a Pharmacy Agreement) to dispense medicines

subsidized under the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS).

An

older study from Australia reported data from 249 myeloma patients

diagnosed from 1975 through 1984 and found no difference in O.S.

according to SES p=0,2 in this decade where chemotherapy was the most

effective treatment.[53] Another

study from Australia

reporting survival data from more than 6000 myeloma patients diagnosed

between 1981 to 2014 found that five-year relative survival across all

treatment eras for disadvantaged patients was 39% (95% CI 0,36–0,42)

vs. affluent patients 46% (95% CI 0,42–0,49) (p<0.001). There

was no

significant difference in relative survival for the middle class in

multivariate analysis than affluent SES patients. Importantly,

residence and SES were significant in multivariate testing,

demonstrating that each was independently predictive of O.S.[54]

New Zealand: Health System

Disparities and the Impact of SES on Myeloma Survival

New

Zealand's original indigenous inhabitants are Māori. In 2014, New

Zealand had an estimated population of 4,547,000. (2) The population

mainly has European ethnicity (74 %), and there are significant Māori

(15%), Pacific Island (7%), and Asian (12%) populations (1).

The

health care system is has been funded by the government since the early

1940s, and public funding currently accounts for 83% of total health

expenditure Government-owned hospitals provide accident and emergency,

inpatient, outpatient, and community care free of charge to all New

Zealanders.

Primary

health care services such as general practitioner (G.P.), pharmacy, and

diagnostic services have traditionally been delivered through privately

owned, small independent businesses funded by the government.

A

recent study from the New Zealand Cancer Registry performed in the era

of modern drugs from 2004 to 2016 has reported in multivariate analysis

age [hazard ratio (HR) 1,06, 95% CI 1,05-1,07], socio-economic

deprivation (HR 1,10, 95% CI 1,04- 1,16) and 4 regions of the country

(HR 1,12, 95% CI 1,05 - 1,19) as negative, and treatment with ASCT (HR

0,66, 95% CI 0,51- 0,87) or bortezomib (HR 0,74, 95% CI 0,64 - 0,86) as

positive independent prognostic factors for OS. The most deprived

groups had an inferior 3-year OS compared to others (57 vs. 63%;

p=0,026) and experienced no improvement in survival following the

funding of bortezomib despite similar uptake of first line bortezomib.[55]

Synthesis

of p values from two cohorts from Australia and a New Zealand cohort

(n=10196 pts) returned a p-value of 0,022 indicated SES as a prognostic

factor and in Oceania (Figure

3B).

United Kingdom: Health System

Disparities and the Impact of SES on Myeloma Survival

The

health care system of the United Kingdom has since 1997 been assigned

the responsibility for organizing health financing and services to

relevant public officials. All U.K. citizens have maintained national

health services, which provide universal access to a comprehensive

package of services that are mostly free at the point of use. These

health services are predominantly financed from general taxation, and

83.5% of total health expenditure in the United Kingdom came from

public sources in 2013.

Life

expectancy has increased steadily across the United Kingdom, but health

inequalities have proved resistant to improvement, and the gap between

the most deprived and the most privileged continues to widen rather

than close.

Renshaw

et al. reported data from 10,015 myeloma patients diagnosed from 1985

through 2004 and included in the Thames Cancer Registry. When

considering patients with myeloma diagnosed in the era of targeted

therapies from 2000 to 2004 in both males and females, there was a

tendency for higher survival in patients resident in the most affluent

areas (males trend p= 0,09, females trend p= 0,07).[56]

Rachet

et al., in another U.K. study, reported data from 40.000 myeloma

patients according to the year of diagnosis and relative deprivation of

social supporting factors (social gap). They found out that the equal

myeloma survival for deprived women noted in the late 1980s had wholly

reversed by the late 1990s. These vast differences among deprivation

groups in survival trends, with no improvement at all in 5-year

survival among the most deprived group, but an increase of more than

10% for the most affluent groups expected to be further widened in the

future.[57]

Greece: Health System Disparities and

the Impact of SES on Myeloma Survival

The

Greek national health system provides healthcare benefits/services

through a network of public/state providers and contracted private

primary, hospital, and ambulatory care providers. Private providers'

presence is more obvious in primary care, especially in diagnostic

technologies, private physicians' practices, and pharmaceuticals. The

system is financed by the state budget, social insurance contributions,

and private payments.

The

National Organization for the Provision of Health Services (Greek

acronym EOPYY) negotiates contracts and remunerates health

professionals. At the Pharmacist's, there is usually a co-payment of

25% of medicinal products' cost. Some patients' groups, such as cancer

patients, the chronically ill, and pregnant women, receive medicines

free of charge or pay a reduced co-payment.

In

a recently published study, we retrospectively collected data from 223

myeloma patients treated in our department from January 2005 till

December 2019. Based on the intention to treat (ITT), 78 patients were

considered transplant eligible (T.E.), and 145 were non-transplant

eligible (NTE). In Kaplan Mayer survival analysis, including all MM

patients of our cohort, the Low SES group n=100 had inferior survival

compared to High SES patients n=123 [Median O.S. (95% CI) for Low SES:

28 months (18-37,9) High SES: 68 months (55,6-80,4), Long Rank

p=0,000). The Low SES effect on O.S. is more evident in the

non-transplant eligible (NTE) elderly myeloma patients and those

diagnosed at I stage ISS.[26]

The

synthesis of p values from the U.K. and Greece studies (n=18533 pts)

returned a p-value of <0,0001 suggested that SES remains an

important prognostic factor of survival in Europe (Figure 3B).

Asia and Africa

A

recent study from China by Limei Xu et al. included 773 NDMM patients

diagnosed from 2006 to 2019 found out that low SES patients received

ASCT at a lower rate and had a worst PFS and O.S. Patients with high

education levels had a median overall survival (O.S.) of 122.27 (95%

CI: 117.05–127.49) months, which was also better than that of patients

with low education levels (58.83 months, 95% CI: 48.87–62.79, p<

0.001). Developing countries contributed two small studies to our

analysis. A small cohort from India reporting data from 132 myeloma

patients diagnosed during the 80s found similar survival rates for low

and middle SES.[58] Similarly,

another study from

Nigeria reports data from 292 newly diagnosed and relapsed myeloma

patients and found no difference in O.S. according to SES p=0,69 in

multivariate analysis.[59]

Synthesis of 2

studies from Asia (n=915 pts) returned a p-value of< 0,0001

showing

a better survival for high SES myeloma patients compared to low SES and

in this part of the world (Figure

3B).

Financial Toxicity of Myeloma

Treatment

Myeloma

is a disease model for drug development that led to 11 new medications'

approval since 1998. Although new treatment allows better disease

control, they also stress payers' budgets. In 2000, the total all-cause

health care cost of myeloma was $3,263 per patient per month (PPPM)

($346 PPPM or 10.6% for myeloma treatment-related drug costs) and

increased to $14,656 PPPM in 2014 ($4,176 PPPM or 28.5% for myeloma

treatment-related drug costs).[60]

Furthermore,

real-world data shows that myeloma patients' treatments are not always

given in optimal ways. MacEwan et al. showed that the average duration

of treatment by a line of therapy was seven months for the first line,

six months for the second line, and five months for the third line.[61] So payments in the real world

setting cannot bring the maximum benefit for myeloma patients.

After

patients are diagnosed with cancer, the purchase of therapies affects

their personal economics (pocket cost) by two ways; first, contributing

to calculations of the cost of insurance premiums and second through

cost-sharing mechanisms imposed by insurers.[1]

Furthermore, employment issues due to myeloma are arising. In a

recently published study, five hundred (66%) of the respondents

reported that they were employed at the time of diagnosis and treatment

onset. However, by the time they completed the study questionnaire,

only 33% were employed.[62] In the

same study, 29% of

participants changed or lost coverage after myeloma diagnosis,

including 10% unable to obtain replacement insurance and 35% applied

for disability support programs.[62]

Considering the

ability to work, this is affected by the choice of an anti-myeloma

treatment plan. Merola et al. reported that patients who received

injectable therapy missed an average of 110 workdays in the one year

after diagnosis, compared with 87 for patients receiving only oral

therapy.[63]

Myeloma

care's financial toxicity is increasing for both health system payers

and for patients' as well. Disparities in myeloma care will widen since

the most deprived will fail to meet the need for continuous

administration of expensive therapies.

Conclusions

SES

is an established poor prognostic factor for survival in many cancers.

Differences in SES are a surrogate marker reflecting other factors like

ethnicity/race, insurance cover, place of living, accessibility to

health services etc. In this meta-analysis, we performed the synthesis

of p values from 16 studies that included 134363 MM patients diagnosed

from 1975 to 2019 and weighted according to the number of patients

included in each study. We demonstrated that SES remains a significant

prognostic factor for O.S. in myeloma patients globally (p-value of

<0,0001). Synthesis of H.R. from 10 studies shows that high SES

myeloma patients have 1,26 (95% CI 1,13-1,31) more probabilities to be

alive at five years compared to low SES patients. Financial

intoxication of myeloma care on health systems and patients is rising

through the decades. Therefore the gap in myeloma care between deprived

and affluent patients is expected to widen in the future.

Acknowledgments

S.Intzes,

M. Symeonidou, and K. Zagoridis reviewed papers and perform statistical

analysis. G Vrachiolias, Z. Bezirgiannidou, and A. Spanoudaki search

literature, export data, and create figures; E. Spanoudakis supervised

research, reviewed papers, and wrote the paper with contributions from

all co-authors.

This

work was supported by an unrestricted educational grant from the

pharmaceutical company FARAN Hellas.

References

- Fonseca R, Hinkel J.

Value and Cost of Myeloma Therapy-We Can Afford It. Am Soc Clin Oncol

Educ Book 2018; 38: 647-655. https://doi.org/10.1200/EDBK_200869

PMid:30231366

- Kumar

L, Cyriac SL, Tejomurtula TV et al. Autologous stem cell

transplantation for multiple myeloma: identification of prognostic

factors. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2013; 13: 32-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clml.2012.08.007

PMid:23085487

- Moreau

P, San Miguel J, Sonneveld P et al. Multiple myeloma: ESMO Clinical

Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol

2017; 28: iv52-iv61. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdx096

PMid:28453614

- Ailawadhi

S, Bhatia K, Aulakh S et al. Equal Treatment and Outcomes for Everyone

with Multiple Myeloma: Are We There Yet? Curr Hematol Malig Rep 2017;

12: 309-316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11899-017-0393-y

PMid:28626849

- Greenberg

AJ, Vachon CM, Rajkumar SV. Disparities in the prevalence, pathogenesis

and progression of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance

and multiple myeloma between blacks and whites. Leukemia 2012; 26:

609-614. https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2011.368

PMid:22193966 PMCid:PMC3629947

- Rosenberg

AS, Brunson A, Jonas BA et al. Association Between Autologous Stem Cell

Transplant and Survival Among Californians With Multiple Myeloma. J

Natl Cancer Inst 2019; 111: 78-85. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djy073

PMid:29897481 PMCid:PMC6335109

- Greenberg

AJ, Philip S, Paner A et a. Racial differences in primary cytogenetic

abnormalities in multiple myeloma: a multi-center study. Blood Cancer J

2015; 5: e271. https://doi.org/10.1038/bcj.2014.91

PMid:25555162 PMCid:PMC5404218

- Kazandjian

D, Hill E, Hultcrantz M et al. Molecular underpinnings of clinical

disparity patterns in African American vs. Caucasian American multiple

myeloma patients. Blood Cancer J 2019; 9: 15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-019-0177-9

PMid:30718460 PMCid:PMC6361959

- Marinac CR, Ghobrial IM,

Birmann BM et al. Dissecting racial disparities in multiple myeloma.

Blood Cancer J 2020; 10: 19. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-020-0284-7

PMid:32066732 PMCid:PMC7026439

- Ailawadhi

S, Frank RD, Advani P et al. Racial disparity in utilization of

therapeutic modalities among multiple myeloma patients: a SEER-medicare

analysis. Cancer Med 2017; 6: 2876-2885. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.1246

PMid:29105343 PMCid:PMC5727310

- Costa

LJ, Huang JX, Hari PN. Disparities in utilization of autologous

hematopoietic cell transplantation for treatment of multiple myeloma.

Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2015; 21: 701-706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.12.024

PMid:25555447 PMCid:PMC4361014

- Fiala

MA, Finney JD, Stockerl-Goldstein KE et al. Re: Disparities in

Utilization of Autologous Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation for

Treatment of Multiple Myeloma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2015; 21:

1153-1154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.03.005

PMid:25771403

- Yun

HD, Dossul T, Bernal-Mizrachi L et al. Referral Patterns and Clinical

Outcomes for Transplant-Eligible Lymphoma and Myeloma Patients

Evaluated at an Urban County Hospital. J Stem Cell Res Ther 2016; 6.

- Bhatnagar

V, Wu Y, Goloubeva OG et al. Disparities in black and white patients

with multiple myeloma referred for autologous hematopoietic

transplantation: a single center study. Cancer 2015; 121: 1064-1070.

https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29160 PMid:25469920

- Ailawadhi

S, Parikh K, Abouzaid S et al. Racial disparities in treatment patterns

and outcomes among patients with multiple myeloma: a SEER-Medicare

analysis. Blood Adv 2019; 3: 2986-2994. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000308

PMid:31648322 PMCid:PMC6849958

- Derman

BA, Jasielec J, Langerman SS et al. Racial differences in treatment and

outcomes in multiple myeloma: a multiple myeloma research foundation

analysis. Blood Cancer J 2020; 10: 80. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-020-00347-6

PMid:32770051 PMCid:PMC7414120

- Verma

PS, Howard RS, Weiss BM. The impact of race on outcomes of autologous

transplantation in patients with multiple myeloma. Am J Hematol 2008;

83: 355-358. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.21139

PMid:18186525

- Schriber

JR, Hari PN, Ahn K.W. et al. Hispanics have the lowest stem cell

transplant utilization rate for autologous hematopoietic cell

transplantation for multiple myeloma in the United States: A CIBMTR

report. Cancer 2017; 123: 3141-3149. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30747

PMid:28472539 PMCid:PMC5544566

- Fillmore

NR, Yellapragada SV, Ifeorah C et al. With equal access, African

American patients have superior survival compared to white patients

with multiple myeloma: a V.A. study. Blood 2019; 133: 2615-2618. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2019000406

PMid:31003998 PMCid:PMC6566591

- Ailawadhi

S, Frank RD, Sharma M et al. Trends in multiple myeloma presentation,

management, cost of care, and outcomes in the Medicare population: A

comprehensive look at racial disparities. Cancer 2018; 124: 1710-1721. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.31237

PMid:29360160

- Albain

KS, Unger JM, Crowley JJ et al. Racial disparities in cancer survival

among randomized clinical trials patients of the Southwest Oncology

Group. J Natl Cancer Inst 2009; 101: 984-992. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djp175

PMid:19584328 PMCid:PMC2724852

- Duma

N, Azam T, Riaz IB et al. Representation of Minorities and Elderly

Patients in Multiple Myeloma Clinical Trials. Oncologist 2018; 23:

1076-1078. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0592

PMid:29700207 PMCid:PMC6192659

- Ailawadhi

S, Jacobus S, Sexton R et al. Disease and outcome disparities in

multiple myeloma: exploring the role of race/ethnicity in the

Cooperative Group clinical trials. Blood Cancer J 2018; 8: 67. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-018-0102-7

PMid:29980678 PMCid:PMC6035273

- Pulte

ED, Nie L, Gormley N et al. Survival of ethnic and racial minority

patients with multiple myeloma treated with newer medications. Blood

Adv 2018; 2: 116-119. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2017010512

PMid:29365319 PMCid:PMC5786427

- Chehab

S, Zhang C, Panjic EH et al. Response to therapeutic monoclonal

antibodies for multiple myeloma in African Americans versus whites.

Cancer 2018; 124: 4358-4365. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.31746

PMid:30303526

- Intzes

S, Symeonidou M, Zagoridis K et al. Socioeconomic Status Is an

Independent Prognostic Factor for Overall Survival in Patients With

Multiple Myeloma: Real-World Data From a Cohort of 223 Patients. Clin

Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2020; 20: 704-711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clml.2020.05.013

PMid:32653455

- Ailawadhi

S, Advani P, Yang D et al. Impact of access to NCI- and NCCN-designated

cancer centers on outcomes for multiple myeloma patients: A SEER

registry analysis. Cancer 2016; 122: 618-625. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29771

PMid:26565660

- Go

RS, Bartley AC, Crowson CS et al. Association Between Treatment

Facility Volume and Mortality of Patients With Multiple Myeloma. J Clin

Oncol 2017; 35: 598-604. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.68.3805

PMid:28199819

- Riva

E, Schutz N, Pena C et al. Significant differences in access to tests

and treatments for multiple myeloma between public and private systems

in Latin America. Results of a Latin American survey. GELAMM (Grupo de

Estudio Latino Americano de Mieloma Multiple). Ann Hematol 2020; 99:

1025-1030. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-020-03983-x

PMid:32157420

- Afshar

N, English DR, Blakely T et al. Differences in cancer survival by

area-level socioeconomic disadvantage: A population-based study using

cancer registry data. PLoS One 2020; 15: e0228551. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0228551

PMid:31999795 PMCid:PMC6992207

- Kish

JK, Yu M, Percy-Laurry A, Altekruse SF. Racial and ethnic disparities

in cancer survival by neighborhood socioeconomic status in

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Registries. J Natl

Cancer Inst Monogr 2014; 2014: 236-243. https://doi.org/10.1093/jncimonographs/lgu020

PMid:25417237 PMCid:PMC4841168

- Le

Floch AC, Eisinger F, D'Incan E et al. Socioeconomic deprivation is

associated with decreased survival in patients with acute myeloid

leukemia. Cancer Epidemiol 2020; 66: 101699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2020.101699

PMid:32179456

- Tao

L, Foran JM, Clarke CA et al. Socioeconomic disparities in mortality

after diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the modern treatment era. Blood

2014; 123: 3553-3562. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-07-517110

PMid:24705494 PMCid:PMC4047495

- Shah

NN, Xi Y, Liu Y et al. Racial and Socioeconomic Disparities in Mantle

Cell Lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2019; 19: e312-e320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clml.2019.03.006

PMid:31029647

- Kahn

JM, Keegan TH, Tao L et al. Racial disparities in the survival of

American children, adolescents, and young adults with acute

lymphoblastic leukemia, acute myelogenous leukemia, and Hodgkin

lymphoma. Cancer 2016; 122: 2723-2730. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30089

PMid:27286322 PMCid:PMC4992431

- Han

X, Jemal A, Flowers CR et al. Insurance status is related to diffuse

large B-cell lymphoma survival. Cancer 2014; 120: 1220-1227. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28549

PMid:24474436

- Ritter

AJ, Goldstein JS, Ayers AA, Flowers CR. Rural and urban patients with

diffuse large B-cell and follicular lymphoma experience reduced overall

survival: a National Cancer DataBase study. Leuk Lymphoma 2019; 60:

1656-1667. https://doi.org/10.1080/10428194.2018.1546855

PMid:30632824 PMCid:PMC6594869

- Rafiq

M, Hayward A, Warren-Gash C et al. Socioeconomic deprivation and

regional variation in Hodgkin's lymphoma incidence in the U.K.: a

population-based cohort study of 10 million individuals. BMJ Open 2019;

9: e029228. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029228

PMid:31542744 PMCid:PMC6756616

- Goldstein

JS, Nastoupil LJ, Han X et al. Disparities in survival by insurance

status in follicular lymphoma. Blood 2018; 132: 1159-1166. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2018-03-839035

PMid:30042094 PMCid:PMC6137560

- Ailawadhi

S, Azzouqa AG, Hodge D et al. Survival Trends in Young Patients With

Multiple Myeloma: A Focus on Racial-Ethnic Minorities. Clin Lymphoma

Myeloma Leuk 2019; 19: 619-623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clml.2019.06.010

PMid:31377212

- Fiala

MA, Finney JD, Liu J et al. Socioeconomic status is independently

associated with overall survival in patients with multiple myeloma.

Leuk Lymphoma 2015; 56: 2643-2649. https://doi.org/10.3109/10428194.2015.1011156

PMid:25651424 PMCid:PMC4831207

- Savage D, Lindenbaum J,

Van Ryzin J et al. Race, poverty, and survival in multiple myeloma.

Cancer 1984; 54: 3085-3094. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19841215)54:12<3085::AID-CNCR2820541246>3.0.CO;2-Z

- Cowan

AJ, Allen C, Barac A et al. Global Burden of Multiple Myeloma: A

Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. JAMA

Oncol 2018; 4: 1221-1227. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.2128

PMid:29800065 PMCid:PMC6143021

- Gebregziabher

M, Bernstein L, Wang Y, Cozen W. Risk patterns of multiple myeloma in

Los Angeles County, 1972-1999 (United States). Cancer Causes Control

2006; 17: 931-938. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-006-0030-x

PMid:16841260

- Demers

PA, Vaughan TL, Koepsell TD et al. A case-control study of multiple

myeloma and occupation. Am J Ind Med 1993; 23: 629-639. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.4700230410

PMid:8338527

- Perrotta

C, Kleefeld S, Staines A et al. Multiple myeloma and occupation: a

pooled analysis by the International Multiple Myeloma Consortium.

Cancer Epidemiol 2013; 37: 300-305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2013.01.008

PMid:23403129

- Sonoda

T, Ishida T, Mori M et al. A case-control study of multiple myeloma in

Japan: association with occupational factors. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev

2005; 6: 33-36.

- Landgren O, Rajkumar

SV,

Pfeiffer RM et al. Obesity is associated with an increased risk of

monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance among black and

white women. Blood 2010; 116: 1056-1059.

https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2010-01-262394 PMid:20421448

PMCid:PMC2938127

- Koessel SL, Theis MK,

Vaughan TL et al. Socioeconomic status and the incidence of multiple

myeloma. Epidemiology 1996; 7: 4-8. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001648-199601000-00002

PMid:8664400

- Sun

T, Wang S, Sun H et al. Improved survival in multiple myeloma, with a

diminishing racial gap and a widening socioeconomic status gap over

three decades. Leuk Lymphoma 2018; 59: 49-58. https://doi.org/10.1080/10428194.2017.1335398

PMid:28595471

- Costa

LJ, Brill IK, Brown EE. Impact of marital Status, insurance status,

income, and race/ethnicity on the survival of younger patients

diagnosed with multiple myeloma in the United States. Cancer 2016; 122:

3183-3190. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30183

PMid:27548407

- Hong

S, Rybicki L, Abounader D et al. Association of Socioeconomic Status

with Outcomes of Autologous Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation for

Multiple Myeloma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2016; 22: 1141-1144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.03.011

PMid:26995694

- Nandakumar

A, Armstrong BK, de Klerk NH. Multiple myeloma in Western Australia: a

case-control study in relation to occupation, father's occupation,

socioeconomic status and country of birth. Int J Cancer 1986; 37:

223-226. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.2910370209

PMid:3080376

- Harwood

M, Dunn N, Moore J et al. Trends in myeloma relative survival in

Queensland by treatment era, age, place of residence, and socioeconomic

status. Leuk Lymphoma 2019; 1-7.

- Chan

HSH, Milne RJ. Impact of age, sex, ethnicity, socioeconomic deprivation

and novel pharmaceuticals on the overall survival of patients with

multiple myeloma in New Zealand. Br J Haematol 2019. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.16238

PMid:31584720

- Renshaw

C, Ketley N, Moller H, Davies EA. Trends in the incidence and survival

of multiple myeloma in South East England 1985-2004. BMC Cancer 2010;

10: 74. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-10-74

PMid:20193064 PMCid:PMC2837016

- Rachet

B, Mitry E, Shah A et al. Survival from multiple myeloma in England and

Wales up to 2001. Br J Cancer 2008; 99 Suppl 1: S110-112. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6604607

PMid:18813241 PMCid:PMC2557530

- Nair MK, Varghese C,

Krishnan E et al. Survival in multiple myeloma in Kerala. Natl Med J

India 1993; 6: 7-10.

- Abou-Jawde

RM, Baz R, Walker E et al. The role of race, socioeconomic status, and

distance traveled on the outcome of African-American patients with

multiple myeloma. Haematologica 2006; 91: 1410-1413.

- Fonseca

R, Abouzaid S, Bonafede M et al. Trends in overall survival and costs

of multiple myeloma, 2000-2014. Leukemia 2017; 31: 1915-1921. https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2016.380

PMid:28008176 PMCid:PMC5596206

- MacEwan

JP, Batt K, Yin W et al. Economic burden of multiple myeloma among

patients in successive lines of therapy in the United States. Leuk

Lymphoma 2018; 59: 941-949. https://doi.org/10.1080/10428194.2017.1361035

PMid:28805105

- Goodwin

JA, Coleman EA, Sullivan E et al. Personal financial effects of

multiple myeloma and its treatment. Cancer Nurs 2013; 36: 301-308. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182693522

PMid:23047800 PMCid:PMC3973128

- Merola

D, Yong C, Noga SJ, Shermock KM. Costs Associated with Productivity

Loss Among U.S. Patients Newly Diagnosed with Multiple Myeloma

Receiving Oral Versus Injectable Chemotherapy. J Manag Care Spec Pharm

2018; 24: 1019-1026. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2018.24.10.1019

PMid:30247101

[TOP]