Fayez Hanna1,2, Annemarie Hyppa2,3, Ajay Prakash1,2, Usira Vithanarachchi1,2, Hizb U Dawar4, Zar Sanga4, George Olabode5, Hamish Crisp5 and Alhossain A. Khalafallah1,2.

1 Faculty of Health Sciences, Launceston, University of Tasmania, Tasmania, 7249, Australia.

2 Department of Haematology, Specialist Care Australia, Launceston, Tasmania, 7250 Australia.

3 Medical School, University of Saarland, Homburg, Germany.

4 Augusta Medical Centre, Lenah Valley 7008, Tasmania, Australia.

5 Launceston General Hospital, Launceston, Tasmania, 7250 Australia.

Correspondence to:

Professor Alhossain A. Khalafallah. University of Tasmania, Australia.

Tel: +61367791300, Fax: +61367791301. E-mail:

a.khalafallah@utas.edu.au

Published: March 1, 2021

Received: November 4, 2020

Accepted: February 5, 2021

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2021, 13(1): e2021017 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2021.017

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Objective:

To study patients receiving anticoagulants with or without antiplatelet

therapy presenting at a regional Australian hospital with bleeding. The

main aims are to explore: (1) patients' characteristics and management

provided; (2) association between the type of anticoagulant and

antiplatelet agent used and the requirement of reversal; (3) and the

length of hospital stay (LoS) in conjunction with bleeding episode and

management.

Methods: A

prospective cross-sectional review of medical records of all patients

who presented at a tertiary referral centre with bleeding while

receiving anticoagulation therapy between January 2016 and June 2018.

Data included: patients, demographics, investigations (kidney and liver function

tests, coagulation profile, FBC), LoS, bleeding site, type of and

reason for anticoagulation therapy, and management provided. Data

analysis included descriptive statistics, χ2 association, and

regression models.

Results: Among the 144 eligible patients, 75 (52.1%) were male, and the mean age was 76 years (SD=11.1). Gastrointestinal tract bleeding was the most common (n=48, 33.3%), followed by epistaxis (n=32, 22.2%). Atrial fibrillation was the commonest reason for anticoagulation therapy (n=65, 45.1%). Warfarin was commonly used (n=74, 51.4%), followed by aspirin (n=29, 20.1%), rivaroxaban (n=26, 18.1%), and apixaban (n=12, 8.3%). The majority had increased blood urea nitrogen (n=67,

46.5%), while 58 (40.3%) had an elevated serum creatinine level, and 59

(41.0%) had a mild reduction in eGFR. Thirty-five of the warfarinised

patients (47.3%) had an INR above their condition's target range

despite normal liver function. Severe anaemia (Hb<80g/L) was

reported in 88 patients (61.1%). DOACs were associated with a reduced

likelihood of receiving reversal (B= -1.7, P=<.001), and with a shorter LoS (B= -4.1, P=.046) when compared with warfarin, LMWH, and antiplatelet therapy.

Conclusion:

Warfarin use was common among patients who presented with acute

bleeding, and the INR in many warfarinised patients exceeded the target

for their condition. DOACs were associated with a reduced likelihood of

receiving reversal and a shorter LoS than warfarin, LMWH, which might

support a broader application of DOACs into community practice.

|

Introduction

One

in every 20 patients will suffer from venous thromboembolism (VTE),

either in the form of DVT alone or in combination with PE.[1]

VTE is associated with high morbidity and mortality rates and

significantly harms the quality of life. Furthermore, it has negative

financial consequences. All of this highlights the need for proper

prevention[2] and treatment. VTE management requires a challenging risk assessment,[2] and measures which may be pharmacological, mechanical, surgical, or a combination.[3] Pharmacological anticoagulation therapy is most common and includes anticoagulants[4] and antiplatelet agents.[5]

Anticoagulants are classified into vitamin K antagonists (such as

warfarin), unfractionated heparin, low molecular weight heparin (LMWH,

e.g., enoxaparin), and the novel direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), including rivaroxaban,

apixaban, and dabigatran.[4] Anticoagulants work by targeting steps in the coagulation cascade.[4]

DOACs achieve an equivalent anticoagulant effect to classical

anticoagulants (warfarin, heparin, and its derivatives) with equal or

reduced bleeding risk.[6-8] While more specific,[9] the

DOACs are more costly than warfarin, which may hinder widespread use in

the community, even though they do not need a specific monitoring test.[10]

Balancing the benefits of anticoagulants against the associated risks

is a concern for clinical practice and requires further real-world

evidence to support decision-making.

The rate of major bleeding

resulting from receiving anticoagulants in Australia is high (seven out

of every 100 patients per year),[11] suggesting the

need for pragmatic, evidence-based guidelines for their use. While the

DOACs have relatively low bleeding risk when compared with warfarin,[8,12,13] clinicians do not tend to use DOACs because they are difficult to monitor and no standard reversal agent is available.[14,15]

The

treatment of patients presenting with bleeding while receiving

anticoagulants with or without antiplatelet agents is based on many

factors, such as the source of bleeding, hemodynamic stability of the

patient, and the severity of blood loss.[16] In major

bleeding, the management provided might include interventions such as

reversing the effect of a therapeutic agent, a surgical achievement of

homeostasis, or a combination of both.[17,18] Since reversal is indicated for severe and life-threatening haemorrhage among such patients,[19]

it might be acceptable to consider reversal-receiving as an indicator

of a severe bleeding episode. There are currently limited studies of

the real-world association between pharmacological anticoagulation

therapy and reversal being implemented in severe and life-threatening

bleeding events. Further, patients who receive a reversal of

anticoagulant therapy often require hospitalisation and recommencement

of anticoagulation therapy. This decision could be challenging, given

the lack of evidence-based guidelines in the selection of therapy.[20,21]

LoS is used extensively in the literature to indicate the severity of a condition and the efficacy and cost of treatment.[22] Moreover, LoS is used as an outcome measure for health services,[23] including quality improvement.[24]

It is worth noting that the use of LoS as an outcome measure should be

taken into account for other individual factors as an indicator of both

bleeding severity and management cost.[24]

Currently, only a few studies have explored the LoS associated with

bleeding events among patients receiving anticoagulation therapy in

Australia.

The aim of this study was to explore the gap between

VTE assessment and management guidelines on the one hand and clinical

practice on the other. This purpose was achieved by investigating

patients receiving anticoagulants with or without antiplatelet agents

who presented with an acute bleeding episode at a regional tertiary

referral hospital, Launceston General Hospital Emergency Department

(LGH-ED). This exploration included the patients' characteristics,

organ function in correlation with their bleeding presentation and the

management provided, type of anticoagulation therapy, the severity of

bleeding, and LoS. Translating the findings into real-world clinical

practice might bridge the knowledge–practice gap in this field.

Methods

Ethics approval.

The project was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee, the

University of Tasmania (H0016734). Because this study was a clinical

audit where patient management was not affected, and patients were not

actively participating, consent was not required from patients; thus,

the Ethics Committee agreed to waive the consent requirement for this

low-risk audit.

Data sampling.

Data sampling was limited to patients who presented to the LGH-ED with

acute bleeding and at the same time were receiving anticoagulation

therapeutic agent(s). The LGH is a tertiary regional referral centre in

Northern Tasmania, and it has the only Emergency Department within a

100-kilometer radius in the region. The LGH has an electronic/digital

medical record (DMR) for all patients presenting to the Emergency

Department. Thus, we conducted an

electronic search for all patients who presented with bleeding in the

period between January 2016 and June 2018. The Pharmacy Department then

checked the records at the LGH to determine whether those patients were

receiving anticoagulation-therapeutic agent(s) in the form of an

anticoagulant with or without antiplatelet agents. Accordingly, only

records that satisfied our selection criteria – presentation with acute

bleeding while receiving anticoagulation therapeutic agent in the form

of DOACs plus/minus antiplatelet agents – were included in the

analysis.

Data collection.

Data were extracted from the LGH patients' DMR. The LGH electronic

patient file and computerised records provided basic demographics such

as age, gender, ethnic group, and language. Further, the system data

provided information about the bleeding episode, including the source

of bleeding, admission/discharge details, management provided, and LoS

in days. The DMR offers data about the indications for administering

anticoagulation therapeutic agent(s) and their doses and results of

routine blood tests carried out on admission for each patient

presenting with bleeding. These tests included full blood count (FBC),

renal function (blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, eGFR), liver

function (ALT, AST albumin, bilirubin), bleeding and coagulation

profile (INR, APTT, PT, platelet count), and intervention

provided.

Data analysis. Data were analysed using SPSS V26.1.[25]

The values of laboratory tests were categorised after adjusting for

gender, as per the reference intervals published by the Royal College

of Pathologists of Australasia or the World Health Organization.[26]

The anticoagulation therapeutic agent(s) were re-categorised based on

the mechanism of action (antiplatelet or anticoagulants). Participants'

characteristics, count, and valid percentages (for non-missing values)

were calculated for categorical variables, and means with standard

deviation (SD) were calculated

for continuous variables. The association between the reason for

administering anticoagulation therapeutic agent(s) and the medication

used was evaluated by a multinomial logistic regression. A Firth

logistic regression model was used to overcome the small sample size to

explore the association between the type of anticoagulation therapeutic

agent(s) and receiving reversal. Finally, an adjusted linear regression

model was used to explore the association between the type of

anticoagulation therapeutic agent(s) used and LoS.

Results

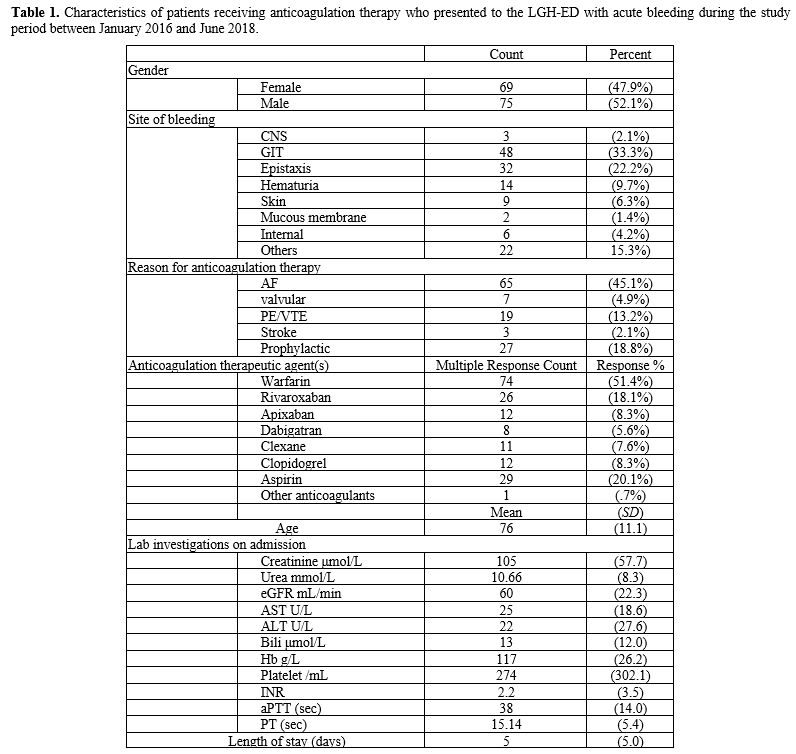

Participant characteristics.

Among the 1501 patients presenting to the ED at the LGH in the period

between January 2016 and June 2018 with a diagnosis of acute bleeding,

only 144 (14.4%) were identified by the Pharmacy Department as

receiving anticoagulation therapeutic agent(s) in the form of

anticoagulants or antiplatelet agents and therefore were eligible for

inclusion in our study. Just over half of patients were males n=75 (52.1%), and the mean age was 76 years (SD=11.1).

Gastrointestinal tract (GIT) bleeding was the most common site of

bleeding in 48 patients (33.3%), followed by epistaxis (n=32,

22.2%), while haematuria was present in 14 patients (9.7%). The most

common reason for administering anticoagulation therapeutic agent(s)

was atrial fibrillation (AF) (n=65,

45.1%), while PE/VTE treatment was documented in 19 patients (13.2%),

and other reasons for anticoagulation therapy were also given (n=27,

18.8%). In a multiple response descriptive analysis for the type of

anticoagulation therapeutic agent(s) used among the patients presented

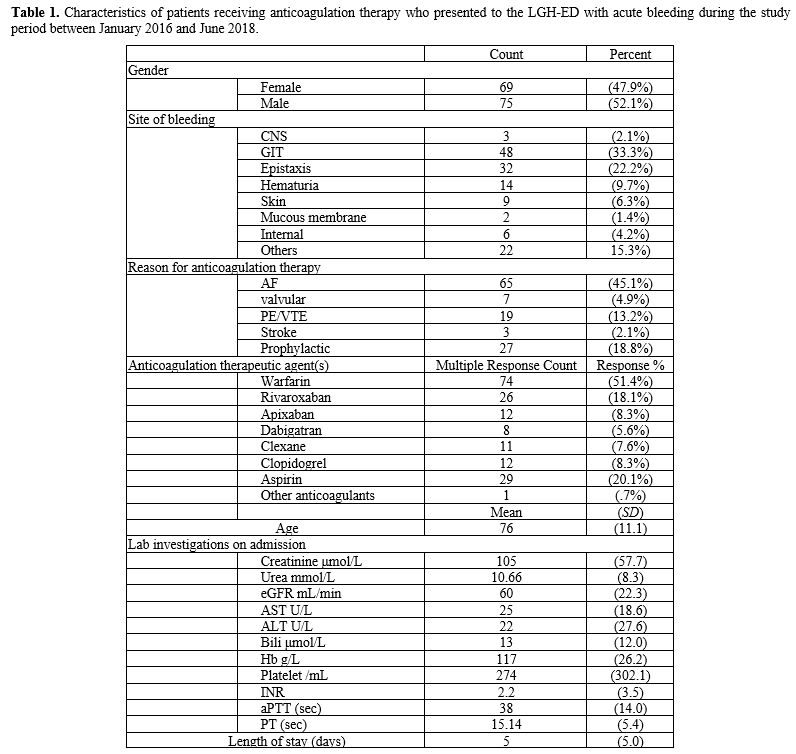

with acute bleeding, warfarin was the most common (n=74, 51.4%), followed by aspirin, which was used by 29 patients (20.1%), then rivaroxaban (n=26, 18.1%). Patients' characteristics are detailed in Table 1.

|

Table

1. Characteristics of patients receiving anticoagulation therapy who

presented to the LGH-ED with acute bleeding during the study period

between January 2016 and June 2018.

|

According

to a multinomial logistic regression model for the type of

anticoagulation therapeutic agent(s) used and the reason for

administration, DOACs were more likely to be used with AF patients (OR=9.6, P=.016) than warfarin (OR=6.1, P=.044). Also, for DVT/PE treatment, LMWH was significantly used (OR=30.0, P=.003) than DOACs when compared with warfarin.

Patient management.

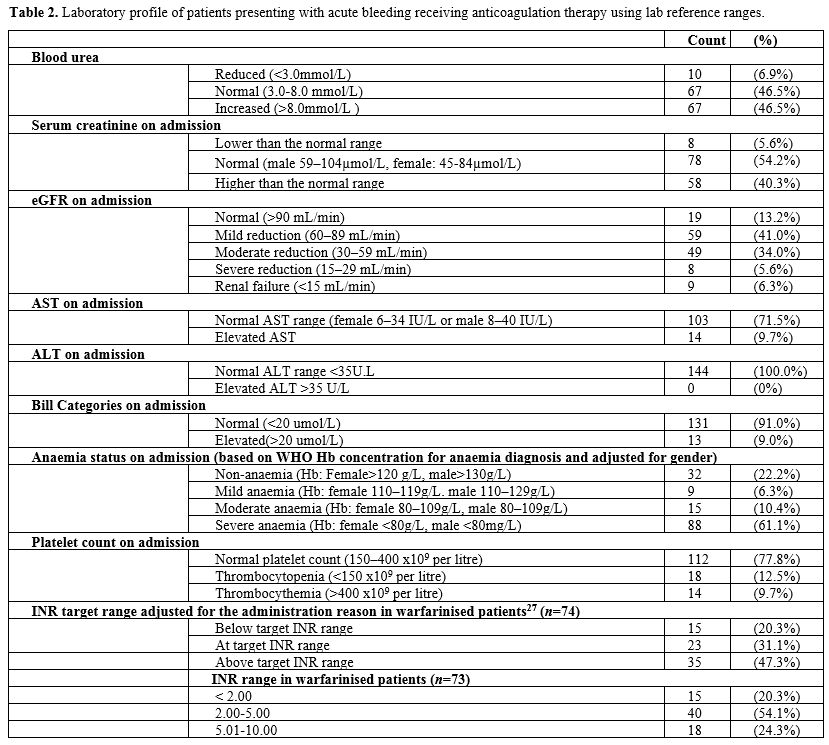

Laboratory investigations.

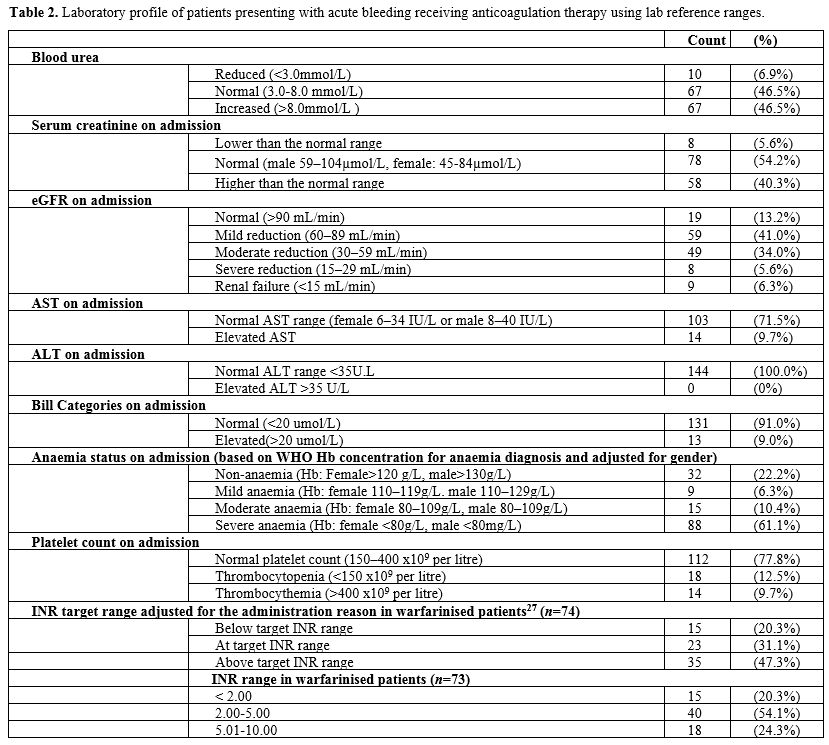

On patients' presentation at the LGH-ED with acute bleeding, routine

laboratory investigations were carried out, including coagulation

profile, FBC, and kidney and liver function for all patients. It was

found that a majority (n=67,

46.5%) had an increased blood urea nitrogen level (>3.0-8.0 mmol/L),

while 59 (41.0%) had a mild reduction in eGFR (60–89 mL/min). The liver

function test showed that most patients had normal AST (n=103, 71.5%), all of them had a normal ALT test (n=144, 100%), and normal bilirubin levels (<20 mmol/L) (n=131, 91.0%). Among those under the vitamin K antagonist warfarin) (n=74), many (n=35, 47.3%) had their INR above the target range (adjusted for the reason of administration),[27] despite a minority having elevated AST (n=14,

18.9%), while all (100%) had normal ALT without a known liver disease.

It is worth noting that no data were available on assays used for

measuring DOACs activities. Most patients (n=112, 77.8%) had a normal platelet count (150-400 x109/L), but a few (n=18, 12.5%) had thrombocytopenia (<150 x109/L), and among them 13 (72.2%) had severe thrombocytopenia (less than 30 x109/L). Thrombocythemia (>400 x109/L) was reported in 14 (9.7%) patients. However, most patients (n=88, 61.1%) were found to have severe anaemia (Hb: female <80g/L, male <80g/L), which was based on the PenaRosas, et al.[26]

guidelines on haemoglobin concentration for diagnosis and assessment of

anaemia severity published by the World Health Organization. Details of

laboratory investigations are found in Table 2.

|

Table

2. Laboratory profile of patients presenting with acute bleeding receiving anticoagulation therapy using lab reference ranges.

|

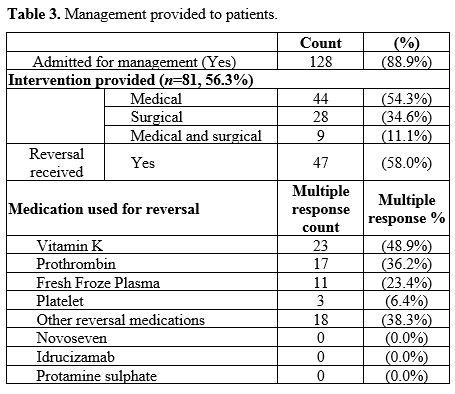

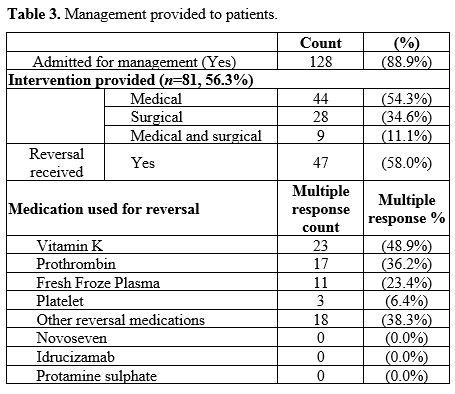

Treatment provided.

Among those patients who presented with bleeding while receiving

anticoagulation therapy, 128 patients (88.9%) were admitted for

management, and 81 patients (56.3%) received an intervention. Among

those patients who received an intervention, medical management was the

most common (n=44, 54.3%) followed by surgical intervention (n=28, 34.6%), such as ligation/cautery of the bleeding vessel, while a few received a combined medical and surgical management (n=9, 11.1%). Among those who received reversal (n=47), by using multiple response descriptive, vitamin K was the most frequent (n=23, 48.9%), while 17 (36.2%) received prothrombin (Table 3).

|

Table 3. Management provided to patients.

|

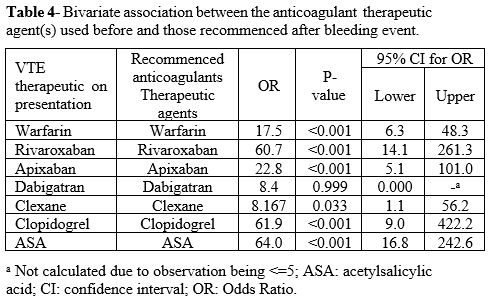

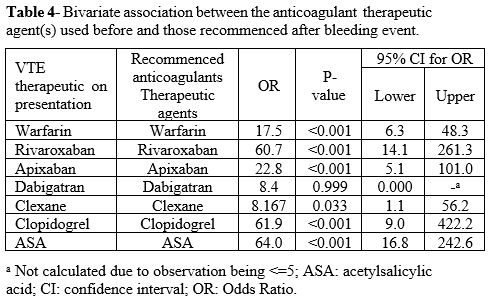

The choice of anticoagulation therapeutic agents on recommencement was similar to the pre-admission agent: warfarin (OR=17.5, P=<.001), rivaroxaban (OR=60.7, P=<.001), apixaban (OR=22.2, P=<.001), clexane (OR=8.1, P=<.033), clopidogrel (OR=61.9, P=<.001), and aspirin (OR=64.0, P=<.001). For more detail, see Table 4.

|

Table 4. Bivariate

association between the anticoagulant therapeutic agent(s) used

before and those recommenced after bleeding event.

|

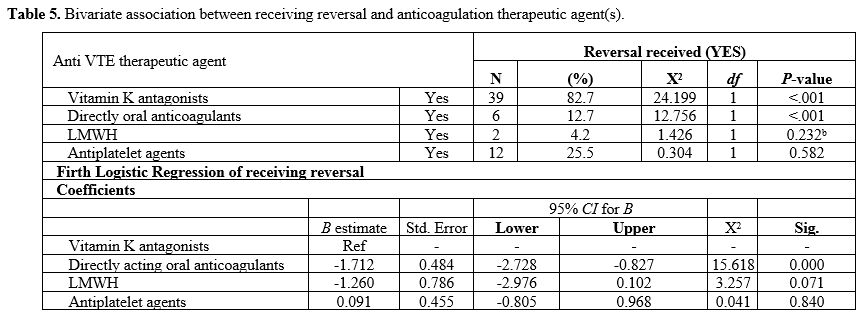

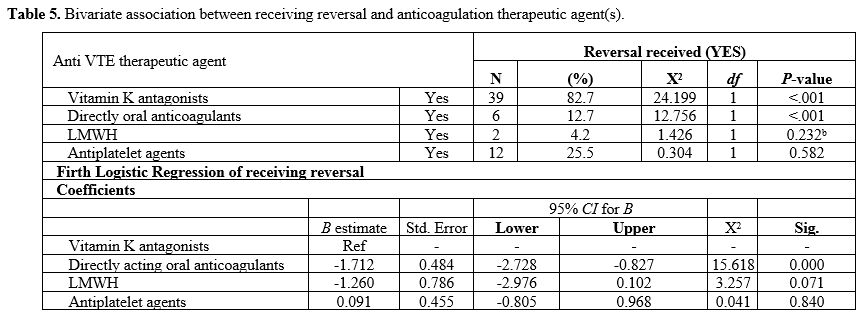

Type of anticoagulation therapeutic agent(s) associated with receiving reversal. Based on a χ2 association for receiving reversal and the type of anticoagulation therapeutic agent(s), vitamin K antagonist (χ2 =24.2, P=<.001) and DOACs (χ2=12.7, P=<.001) were significantly associated with receiving reversal (Table 5).

Using a Firth logistic regression, DOACs use was associated with a

reduced likelihood of receiving reversal compared with vitamin K

antagonists (B=-1.7, P=<.001), as shown in Table 5.

It is worth noting that idarucizumab is the approved reversal for

dabigatran in Australia. We observed the use of other options[19] for reversing the effect of DOACs in some cases, such as prothrombin complex and fresh frozen plasma.

|

Table 5. Bivariate association between receiving reversal and anticoagulation therapeutic agent(s).

|

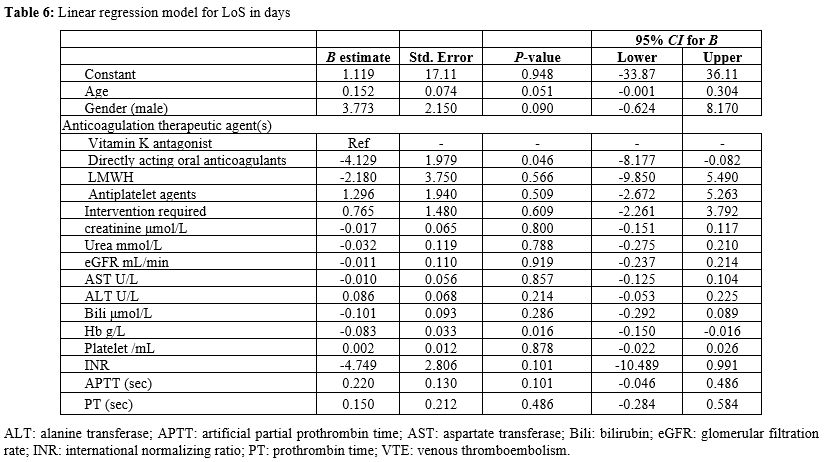

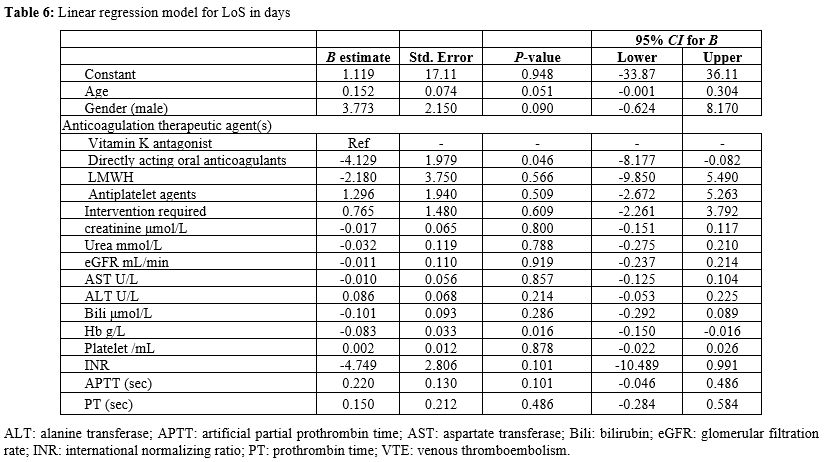

Association

between the type of anticoagulation therapeutic agent and LoS due to

the acute bleeding event in an adjusted linear regression model. In an adjusted linear regression model for LoS in days, DOACs were associated with a significantly shorter LoS (B=-4.1, 95% CI: -8.177, -0.082, P=0.046)

when compared with vitamin K antagonist (warfarin); additionally, a

higher haemoglobin concentration on admission was associated with a

shorter LoS (B=-0.083, 95% CI: -0.150- -0.016, P=0.016) (Table 6).

|

Table

2. Linear regression model for LoS in days

|

Discussion

This

study illustrates the characteristics and profile of patients receiving

different anticoagulation therapy – in the form of oral anticoagulants

including DOAC and antiplatelet agents – who presented with acute

bleeding at a regional tertiary hospital in Tasmania, Australia. The

associations between the type of anticoagulation therapeutic agent on

the one hand and the severity of bleeding and receiving reversal

agent(s) on the other, in conjunction with LoS, were studied. The study

showed that warfarin was a frequent anticoagulation therapeutic agent

among patients who presented with bleeding. Additionally, many of those

warfarinised patients had INRs above the desired target range for the

condition being administered. While conventional coagulation profile

tests were requested for most patients, no agent-specific laboratory

tests were requested for patients receiving DOACs. When compared with

warfarin, DOACs use was more common in patients with AF. It is worth

noting that the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) approves

dabigatran in non-valvular AF patients only; rivaroxaban and apixaban

are approved for both non-valvular AF and anticoagulation-treatment and

prophylaxis. While most patients were admitted for management, many had

already received medical management to reverse the effect of the

anticoagulation therapeutic agent(s). The reversal agents were less

likely to be used with DOACs than warfarin and other anticoagulation

therapeutic agents (s). On exploring the association between LoS and

individual agents (in an adjusted analysis), the use of DOACs was

associated with a shorter LoS than LMWH or antiplatelets compared to

warfarin. It is worth mentioning that LoS was longer when the patient

had lower haemoglobin concentration on admission.

The study findings might enhance the use of DOACs,[28]

which were introduced about ten years ago in Australia and had a steady

prescription pattern at the present study time. However, because the

study did not weigh the prevalence of these medications' prescription

rates, caution should be exercised. Overall, the recommended target INR

range was not achieved in many patients who received warfarin and

presented with bleeding.[29] This suggests the need

for continued educational development on pharmacological

anticoagulation therapy and clear guidelines and decision aids for

medical professionals. While most patients had global coagulation

tests, it is argued that these tests are not reliable in patients

receiving DOACs.[30] Some assays are currently available for DOACs, such as ecarin clotting time (ECT) and chromogenic anti-FXa,[18]

but they were seldom requested by the ED physicians in this study. This

finding might suggest the need to improve medical practitioners'

knowledge about more reliable tests for measuring DOACs activity.

The majority (n=128,

88.9%) of patients who had bleeding because of anticoagulation

therapeutic agents were admitted for management. Thirty-one patients

(24%) needed reversal. However, this study was able to identify that

patients on DOACs were less likely to receive reversal when compared

with those who were on warfarin or LMWH. This finding supports the

wider implementation of DOACs[28] when compared with

warfarin and other anticoagulation therapeutic agents. The real-world

association between receiving reversal in patients who presented with

life-threatening bleeding due to anticoagulation therapy is very

difficult to obtain using other research designs, considering that

prolonged cohort studies require substantial resources. However, the

present study arrived at the same inference using a cross-sectional

design.

Furthermore, the present study was able to find a

significant association between pre-and post-bleeding pharmacological

anticoagulation therapeutic agents. In contrast, dabigatran and clexane

were less likely to be used on the resumption of pharmacological

anticoagulation therapy when compared with other agents. It is worth

noting that, in Australia, dabigatran and antiplatelet agents are not

indicated for the treatment of VTE. Accordingly, this finding ought to

be explored in future research.

Using an adjusted analysis[24] for LoS, it was found that DOACs were associated with a shorter LoS (P=0.046) compared with warfarin, LMWH, and antiplatelets. This finding was consistent with two recent studies.[31,32] These studies have concluded that DOACs were significantly associated with a shorter LoS compared to warfarin.[31,32]

Furthermore,

there is evidence that DOACs cost significantly less than warfarin for

hospitalisation due to a specific bleeding event with blunt traumatic

intracranial hemorrhage.[22] However, what is novel

in the current study was the wide variety of the bleeding sites and the

wide range of anticoagulation therapeutic agents used for various

reasons, such as VTE prophylaxis or treatment, in correlation with

coagulation profile and kidney and liver function and management and or

interventions that were conducted at the time of presentation. Although

it might be argued that upfront costs for warfarin administration are

cheaper when compared with DOACs,[10] our finding

suggests that DOACs are more cost-effective overall in the long run when

compared with warfarin or other agents, considering the reduced

likelihood of patients' presentations to ED and receiving reversal and

the significantly shorter LoS.

Recent literature showed that

DOACs have a better safety profile than warfarin, particularly

intracranial and subarachnoid haemorrhage.[33]

Moreover, rivaroxaban appears to be better than warfarin in limitation

of blood-brain barrier disruption after intracranial haemorrhage.[34]

In addition to the VTE prophylaxis effect, DOACs show non-inferior

results and superior results compared to warfarin in the management of

non-valvular atrial fibrillation and prevention of stroke, especially

after the availability of reversal agents such as idarucizumab.[35] In this regard, Coons et al. demonstrated in an extensive study of 1840 patients with morbid obesity (BMI>40 kg/m2) and VTE that DOACs are more effective and less risky than warfarin.[36]

In another study, there was no advantage of warfarin over DOACs as VTE

prophylaxis in patients who have cancer or atrial fibrillation.[37]

It

is worth noting that in our hands that the use of DOACs in the studied

cohort with renal impairment was not associated with excessive bleeding

as occurs with warfarin. In comparison to warfarin, the safety of DOACs

in case of chronic kidney disease (CKD) was always a concern among

clinicians. A recent study by Weber, found that apixaban is safer than warfarin in CKD.[38]

Nonetheless, careful consideration of anticoagulation's desired level

and anticoagulant dose to achieve the best possible anticoagulation

effect and outcome is warranted.[39] It is worth

noting that there are no reliable, up-to-date guidelines for

recommending DOACs in different doses in case of impaired renal

function.[40] However, in practice, DOACs are

considered to have a similar or safer profile compared to warfarin in

mild to moderate renal impairment, but this is not the case in severe

renal impairment, especially in the renal transplant setting.[41]

This

study's main limitation was the small sample size yielded from our

perspective cross-sectional sampling of patients during the sampling

timeframe. However, the same approaches were used to overcome the small

sample size by re-categorising anticoagulation therapeutic agents and

using statistical methods such as the Fisher's exact test and Firth

logistic regression. It may be worth noting that some studies, such as

the one conducted by Lamb et al.[22] in the USA, have

investigated a closely-related topic but relied on smaller sample size.

On the other hand, the present study has several strengths: it included

all patients who had bleeding secondary to anticoagulant with or

without antiplatelet agents in an entire regional population in mid and

north of Tasmania. The LGH is the only tertiary referral hospital in

this area, and any patient with acute bleeding would be referred to it.

The study contributes to clinical practice by showing the need for

better control and effective monitoring of patients on pharmacological

anticoagulation therapeutic agents based on administration.

Additionally,

our study contributes to research on health services cost-effectiveness

by showing that the use of DOACs is associated with a reduced

likelihood of receiving reversal and shorter LoS in the absence of

life-threatening bleeding compared with warfarin. Furthermore, this

study contributes to clinical decision-making with respect to selecting

anticoagulation therapeutic agents by showing that reduced morbidity

was associated with the use of DOACs compared with warfarin. This study

contributed to translational medical research by obtaining real-world

evidence on risk assessment and management in patients receiving

anticoagulation therapy who presented with bleeding while considering

the available guidelines and practice information.

Conclusions

Despite

the limitations of our study, it is suggested that the application of

DOACs is associated with fewer bleeding complications compared to

warfarin. Further, bleeding in DOAC was shown to be less severe in our

cohort study with reduced LoS that encourage DOACs' use, although the

costs due to the fact of their pharmacodynamic reversal is not often

required.

DOACs were associated with a reduced likelihood of

receiving reversal, a shorter LoS, and better overall clinical

outcomes. The guidelines should probably address and include better

indicators for DOACs bleeding risk, such as ECT and Chromogenic

anti-FXa. Therefore, ECT and chromogenic anti-FXa should be better

understood and utilised in the context of bleeding associated with

DOACs among clinicians, especially in the Emergency Department.

References

- Bungard TJ, Ritchie B, Bolt J, Semchuk WM.

Anticoagulant therapies for acute venous thromboembolism: a comparison

between those discharged directly from the emergency department versus

hospital in two Canadian cities. BMJ Open 2018;8(10):e022063. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022063 PMid:30385438 PMCid:PMC6224720

- Noel SE, Millar JA. Current state of medical thromboprophylaxis in Australia. The Australasian Medical Journal 2014;7(2):58-63. https://doi.org/10.4066/AMJ.2014.1915 PMid:24611073 PMCid:PMC3941577

- Kakkos

SK, Warwick D, Nicolaides AN, Stansby GP, Tsolakis IA. Combined

(mechanical and pharmacological) modalities for the prevention of

venous thromboembolism in joint replacement surgery. The Journal of

Bone and Joint Surgery 2012;94(6):729-734. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.94B6.28128 PMid:22628585

- Moheimani

F, Jackson DE. Venous thromboembolism: Classification, risk factors,

diagnosis, and management. ISRN Hematology 2011;2011:e124610. https://doi.org/10.5402/2011/124610 PMid:22084692 PMCid:PMC3196154

- Watson

HG, Chee YL. Aspirin and other antiplatelet drugs in the prevention of

venous thromboembolism. Blood Reviews 2008;22(2):107-116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.blre.2007.11.001 PMid:18226435

- Harter

K, Levine M, Henderson SO. Anticoagulation drug therapy: a review.

Western Journal of Emergency Medicine 2015;16(1):11-17. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2014.12.22933 PMid:25671002 PMCid:PMC4307693

- Kimachi

M, Furukawa TA, Kimachi K, Goto Y, Fukuma S, Fukuhara S. Direct oral

anticoagulants versus warfarin for preventing stroke and systemic

embolic events among atrial fibrillation patients with chronic kidney

disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

2017;2017(11):CD011373. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011373.pub2 PMid:29105079 PMCid:PMC6485997

- Gomez-Outes

A, Terleira-Fernandez AI, Lecumberri R, Suarez-Gea ML,

Vargas-Castrillon E. Direct oral anticoagulants in the treatment of

acute venous thromboembolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Thrombosis Research 2014;134(4):774-782. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2014.06.020 PMid:25037495

- TGA.

New oral anticoagulants - apixaban (Eliquis), dabigatran (Pradaxa) and

rivaroxaban (Xarelto) Australia: The Australian Government Theraputic

Goods Administration; 2015 [Available from: https://www.tga.gov.au/node/705240

- Ortiz-Cartagena

L, Gotay AO, Acevedo J. Cost effectiveness of oral anticoagulation

therapy for non-valvular atrial fibrillation patients: Warfarin versus

the new oral anticoagulants rivaroxaban, dabigatran and apixaban.

Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2018;71(11):A490. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-1097(18)31031-3

- Shoeb

M, Fang MC. Assessing bleeding risk in patients taking anticoagulants.

Journal of Thrombosis and Thrombolysis 2013;35(3):312-319. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-013-0899-7 PMid:23479259 PMCid:PMC3888359

- Hamidi

M, Zeeshan M, Sakran JV, Kulvatunyou N, O'Keeffe T, Northcutt A,

Zakaria ER, Tang A, Joseph B. Direct oral anticoagulants vs

low-molecular-weight heparin for thromboprophylaxis in nonoperative

pelvic fractures. Journal of the American College of Surgeons

2018;228(1):89-97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.09.023 PMid:30359834

- Bungard

TJ, Ritchie B, Bolt J, Semchuk WM. Management of acute venous

thromboembolism among a cohort of patients discharged directly from the

emergency department. BMJ Open 2018;8(10):e022064. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022064 PMid:30385439 PMCid:PMC6224769

- Scheres

LJJ, Lijfering WM, Middeldorp S, Cheung YW, Barco S, Cannegieter SC,

Coppens M. Measurement of coagulation factors during rivaroxaban and

apixaban treatment: results from two crossover trials. Research and

Practice in Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2018;2(4):689-695. https://doi.org/10.1002/rth2.12142 PMid:30349888 PMCid:PMC6178718

- Ebner

M, Birschmann I, Peter A, Hartig F, Spencer C, Kuhn J, Rupp A,

Blumenstock G, Zuern CS, Ziemann U, Poli S. Limitations of specific

coagulation tests for direct oral anticoagulants: a critical analysis.

Journal of the American Heart Association 2018;7(19):e009807. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.118.009807 PMid:30371316 PMCid:PMC6404908

- Dhakal

P, Rayamajhi S, Verma V, Gundabolu K, Bhatt VR. Reversal of

anticoagulation and management of bleeding in patients on

anticoagulants. Clinical and Applied Thrombosis/Hemostasis

2017;23(5):410-415. https://doi.org/10.1177/1076029616675970 PMid:27789605

- Anderson

I, Cifu AS. Management of bleeding in patients taking oral

anticoagulants. JAMA Journal of American Medical Association

2018;319(19):2032-2033. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.3504 PMid:29800198

- Eikelboom

J, Merli G. Bleeding with direct oral anticoagulants vs warfarin:

clinical experience. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine

2016;34(11S):S33-S40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.06.003 PMid:27586367

- Almegren M. Reversal of direct oral anticoagulants. Vascular Health and Risk Management 2017;13:287-292. https://doi.org/10.2147/VHRM.S138890 PMid:28769570 PMCid:PMC5529093

- Qureshi

W, Mittal C, Patsias I, Garikapati K, Kuchipudi A, Cheema G, Elbatta M,

Alirhayim Z, Khalid F. Restarting anticoagulation and outcomes after

major gastrointestinal bleeding in atrial fibrillation. The American

Journal of Cardiology 2014;113(4):662-668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.10.044 PMid:24355310

- Witt

DM. What to do after the bleed: resuming anticoagulation after major

bleeding. American Society of Hematology Education Program

2016;2016(1):620-624. https://doi.org/10.1182/asheducation-2016.1.620 PMid:27913537 PMCid:PMC6142471

- Lamb

LC, DiFiori M, Comey C, Feeney J. Cost analysis of direct oral

anticoagulants compared with warfarin in patients with blunt traumatic

intracranial hemorrhages. American Surgeon 2018;84(6):1010-1014. https://doi.org/10.1177/000313481808400657

- Sarkies

MN, Bowles KA, Skinner EH, Mitchell D, Haas R, Ho M, Salter K, May K,

Markham D, O'Brien L, Plumb S, Haines TP. Data collection methods in

health services research: hospital length of stay and discharge

destination. Applied Clinical Informatics 2015;6(1):96-109. https://doi.org/10.4338/ACI-2014-10-RA-0097 PMid:25848416 PMCid:PMC4377563

- Brasel

KJ, Lim HJ, Nirula R, Weigelt JA. Length of stay: an appropriate

quality measure? Archives of Surgery 2007;142(5):461-465. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.142.5.461 PMid:17515488

- IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows [program]. 26.1 version. NY, USA: IBM Corporation, 2020.

- PenaRosas

JP, Cusick S, Lynch S. Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of

anaemia and assessment of severity. World Health Organization. 2011.

Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/85839/WHO_NMH_NHD_MNM_11.1_eng.pdf?ua=1

- Liew

J, Mathers S. Guideline for the Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism

(VTE) in Adult Hospitalised Patients. Queensland Health. Queensland,

Australia, 2018. Available from: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0031/812938/vte-prevention-guideline.pdf

- Raschi

E, Bianchin M, Ageno W, De Ponti R, De Ponti F. Risk-benefit profile of

direct-acting oral anticoagulants in established therapeutic

indications: an overview of systematic reviews and observational

studies. Drug Safety 2016;39(12):1175-1187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-016-0464-3 PMid:27696300 PMCid:PMC5107188

- Wallace

R, Anderson MA, See K, Gorelik A, Irving L, Manser R. Venous

thromboembolism management practices and knowledge of guidelines: a

survey of Australian haematologists and respiratory physicians.

Internal Medicine Journal 2017;47(4):436-446. https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.13382 PMid:28150371

- Adcock DM, Gosselin R. Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs) in the laboratory: 2015 review. Thrombosis Research 2015;136(1):7-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2015.05.001 PMid:25981138

- Badreldin

H. Hospital length of stay in patients initiated on direct oral

anticoagulants versus warfarin for venous thromboembolism: a real-world

single-center study. Journal of Thrombosis and Thrombolysis

2018;46(1):16-21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-018-1661-y PMid:29626281

- Charlton

B, Adeboyeje G, Barron JJ, Grady D, Shin J, Redberg RF. Length of

hospitalization and mortality for bleeding during treatment with

warfarin, dabigatran, or rivaroxaban. PLoS One 2018;13(3):e0193912. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193912 PMid:29590141 PMCid:PMC5874024

- Paravattil

B, Elewa H. Approaches to Direct Oral Anticoagulant Selection in

Practice. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther 2018:1074248418793137. https://doi.org/10.1177/1074248418793137 PMid:30092658

- Sawada

S, Ono Y, Egashira Y, Takagi T, Tsuruma K, Shimazawa M, Iwama T, Hara

H. In Models of Intracerebral Hemorrhage, Rivaroxaban is Superior to

Warfarin to Limit Blood Brain Barrier Disruption and Hematoma

Expansion. Curr Neurovasc Res 2017;14(2):96-103. https://doi.org/10.2174/1567202613666161216150835 PMid:27993122

- Rawal

A, Ardeshna D, Minhas S, Cave B, Ibeguogu U, Khouzam R. Current status

of oral anticoagulant reversal strategies: a review. Ann Transl Med

2019;7(17):411. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm.2019.07.101 PMid:31660310 PMCid:PMC6787376

- Coons

JC, Albert L, Bejjani A, Iasella CJ. Effectiveness and Safety of Direct

Oral Anticoagulants versus Warfarin in Obese Patients with Acute Venous

Thromboembolism. Pharmacotherapy 2020;40(3):204-210. https://doi.org/10.1002/phar.2369 PMid:31968126

- Shah

S, Norby FL, Datta YH, Lutsey PL, MacLehose RF, Chen LY, Alonso A.

Comparative effectiveness of direct oral anticoagulants and warfarin in

patients with cancer and atrial fibrillation. Blood Adv

2018;2(3):200-209. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2017010694 PMid:29378726 PMCid:PMC5812321

- Weber

J, Olyaei A, Shatzel J. The efficacy and safety of direct oral

anticoagulants in patients with chronic renal insufficiency: A review

of the literature. Eur J Haematol 2019;102(4):312-318. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejh.13208 PMid:30592337

- Shrestha

S, Baser O, Kwong WJ. Effect of Renal Function on Dosing of Non-Vitamin

K Antagonist Direct Oral Anticoagulants Among Patients With Nonvalvular

Atrial Fibrillation. Ann Pharmacother 2018;52(2):147-153. https://doi.org/10.1177/1060028017728295 PMid:28856898

- Padrini

R. Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Direct Oral

Anticoagulants in Patients with Renal Failure. Eur J Drug Metab

Pharmacokinet 2019;44(1):1-12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13318-018-0501-y PMid:30167998

- Kcükköylü S, Rump LC. DOAC use in patients with chronic kidney disease. Hamostaseologie 2017;37(4):286-294. https://doi.org/10.5482/HAMO-17-01-0003 PMid:29582930

[TOP]