Mohamed Hussien Ahmed1, Mohamed H Emara1, Amr Asem Elfert2, Aymen M. El-Saka3, Asem Ahmed Elfert4, Sherief Abd-Elsalam4 and Mohamed Yousef4..

1 Hepatology, Gastroenterology and Infectious Diseases Department, Kafrelsheikh University, Kafrelsheikh, Egypt.

2 Department of Pathology, College of Medicine, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL, United States.

3 Department of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, Tanta University, Egypt.

4 Department of Tropical Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Tanta University, Tanta, Egypt.

Published: May 1, 2021

Received: January 17, 2021

Accepted: April 11, 2021

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2021, 13(1): e2021033 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2021.033

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Background and Aims: Human

schistosomiasis is one of the most important and unfortunately

neglected tropical diseases. The aim of the current study was to

investigate the prevalence and characteristics of colonic

schistosomiasis among symptomatic rural inhabitants of the Middle

Northern region of the Egyptian Nile delta.

Patients and Methods:

This study recruited 193 inhabitants of the rural community in the

Egyptian Nile Delta referred for colonoscopy because of variable

symptoms. After giving written informed consent, they were exposed to

thorough history, clinical examination, stool analysis, abdominal

ultrasonography, and pan-colonoscopy with biopsies.

Results: Twenty-four

cases out of the 193 patients had confirmed active schistosomiasis with

a prevalence rate of 12.4%. Bleeding with stool was the predominant

manifestation of active Schistosoma infection among the cases either

alone or in combination with abdominal pain. On clinical examination,

most patients (n=17; 70.8%) did not have organomegaly, and 25% had

clinically palpable splenomegaly as far as 75% of them had

sonographically detected hepatic peri-portal fibrosis. Also, 66.6% of

patients have significant endoscopic lesions (polyps, ulcers, mass-like

lesions), and 16.6% of them had colonic affection beyond the

recto-sigmoid region.

Conclusion: Colonic

schistosomiasis is still prevalent among the Egyptian Nile Delta's

symptomatic rural inhabitants at a rate of 12.4%. Of them, 66.6% had

significant endoscopic colorectal lesions. This persistent transmission

of schistosomiasis in the Egyptian Nile Delta's rural community sounds

the alarm for continuing governmental efforts and plans to screen the

high-risk groups. The prevalence rate reported in the current study is

lower than the actual prevalence rate of schistosomiasis due to

focusing only on a subgroup of individuals.

|

Introduction

Human

schistosomiasis (Bilharziasis) is one of the most important neglected

tropical diseases currently not receiving enough public attention. It

is endemic in 77 countries in the tropical and subtropical communities,

with about 250 million individuals worldwide infected.[1] The Middle East and North Africa (MENA region) represented an endemic hot spot for schistosomiasis late in the 20thcentury.[2,3]

In Egypt, Schistosoma mansoni (S. mansoni)

has almost totally replaced Schistosoma haematobium in the Nile Delta

and spread to other regions of the country since the middle of the 20th construction century of the High Dam.[4]

Ongoing

control measures have markedly decreased the incidence of the disease.

The disease's characteristics have changed as a result of the

government-sponsored mass treatment campaigns, implemented over the

past decades, that succeeded in reducing the prevalence of infection

all over Egypt from 3% in 2003 to 0.3% in 2012.[5]

However,

the transmission may remain ongoing due to the widespread distribution

of the intermediate snail host, poor sanitation, lack of health

education, and decreased treatment availability, especially among the

high-risk groups.[6] Furthermore, the data about the newly acquired infections in Egypt is scarce.

Among the high-risk groups who may maintain schistosomiasis' ongoing transmission are the farmers and fishermen.[4,7-9]

The

farmers and fishermen in the Egyptian Nile Delta's geographic area

mainly reside in the rural countryside. They cultivate and fish in

brackish water, harboring the schistosoma snail intermediate host, and

they sometimes practice promiscuous defecation in the water.

Consequently, they act as both victims susceptible to be infected and

offenders disseminating the infection.[8-10]

The

aim of the current study was to investigate the prevalence and

characteristics of colonic schistosomiasis among symptomatic adult

rural inhabitants of the Middle Northern region of the Egyptian Nile

delta.

Patients and Methods

Study area.

Subjects of the current study were symptomatic inhabitants of the rural

community attending the endoscopy units of both the Department of

Hepatology, Gastroenterology and Infectious Diseases, Kafrelshiekh

University, Egypt, and the Tropical Medicine Department, Tanta

University, Egypt. Attendants to both units reside in Kafr-El-Sheikh

and Gharbia governorates. Both governorates are located in the Middle

and North of the Nile Delta. The Western and Eastern borders of this

geographic area are the Rosetta and Damietta branches of the River

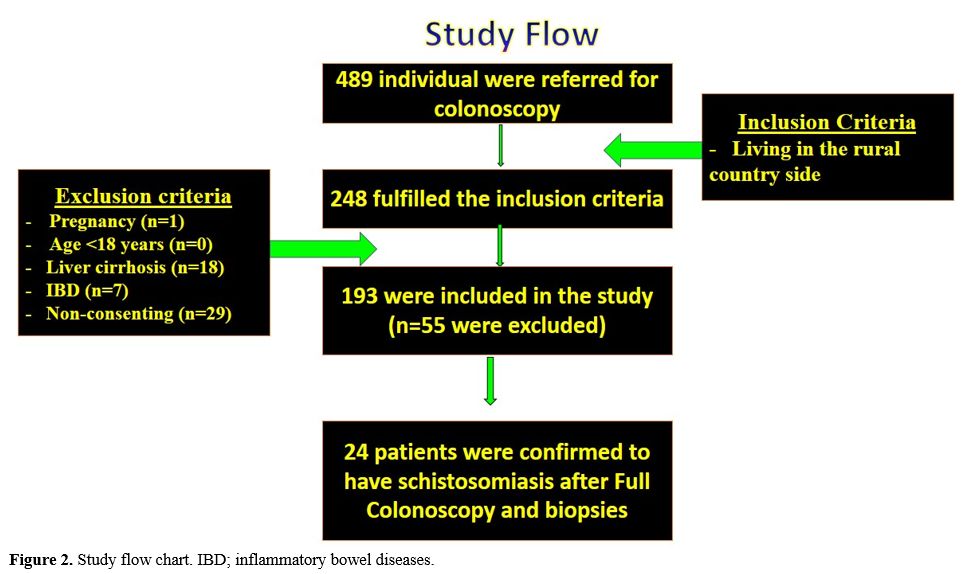

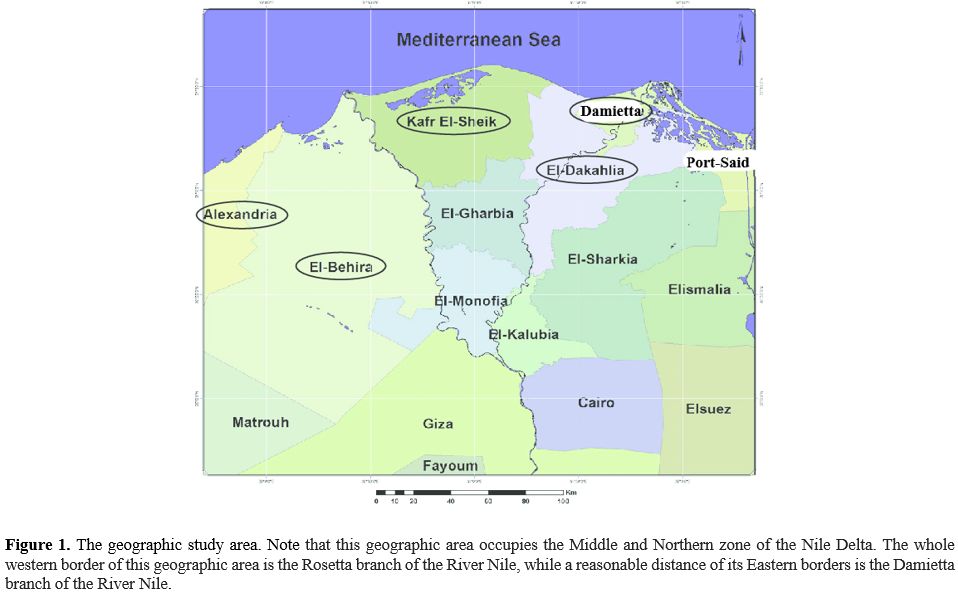

Nile. The Northern border is the Mediterranean Sea (Figure 1). The area of the Nile delta is considered an endemic area for S. mansoni infection.[10]

|

Figure 1. The geographic

study area. Note that this geographic area occupies the Middle and

Northern zone of the Nile Delta. The whole western border of this

geographic area is the Rosetta branch of the River Nile, while a

reasonable distance of its Eastern borders is the Damietta branch of

the River Nile.

|

Kafr-El-Sheikh

and Gharbia governorates are agricultural districts. In this rural

community of the Nile Delta, inhabitants are primarily farmers and, to

a lesser extent, fishermen. They practice agriculture and fishing in

potentially infected water supplies.

Ethical consideration.

Permission and official approval to carry out the study was obtained.

All patients signed a written informed consent prior to inclusion into

this study, and the institutional ethical committee in Tanta University

Faculty of Medicine approved the study. The study protocol conforms to

the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

Study design. A cross-sectional study:

a)

Our study's primary end-point was determining the percentage of

symptomatic adult inhabitants in the rural community with active

colonic schistosomiasis.

b) Our study's

secondary end-points were to characterize clinical, sonographic

features of colonic schistosomiasis besides the extent of the schistosoma induced pathology in the colon.

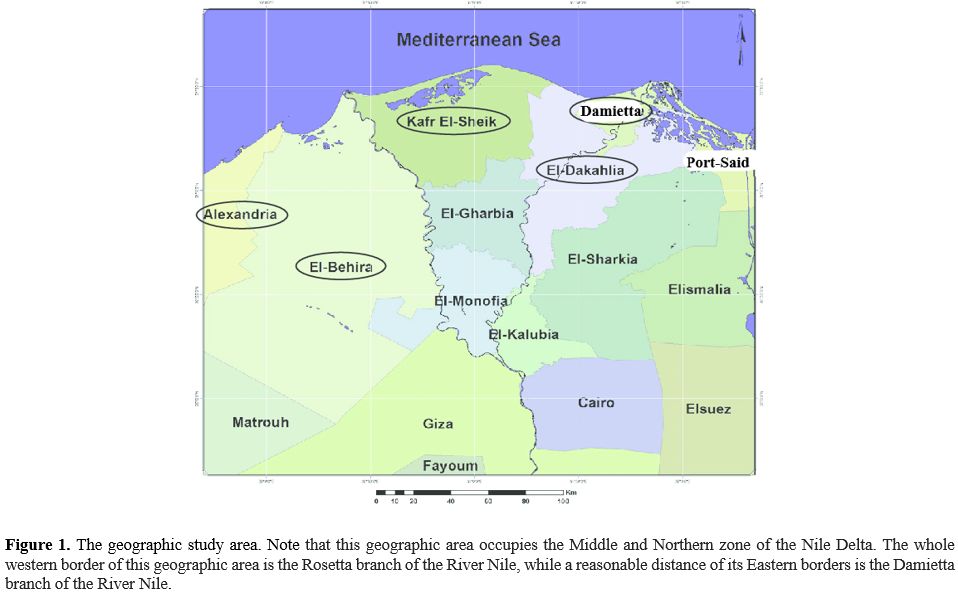

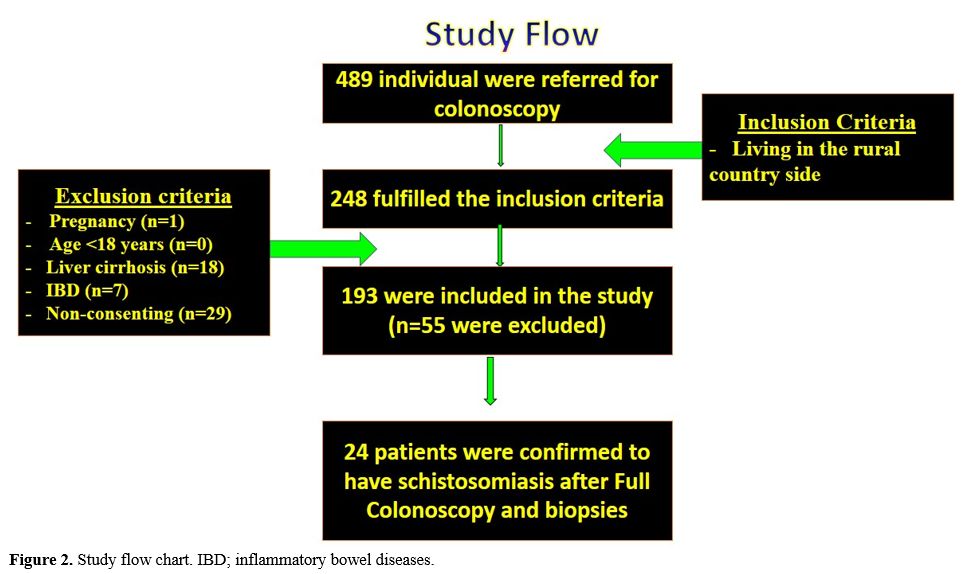

c) Inclusion criteria (Figure 2): Patients with the following criteria were recruited

- Any gender

- Living in the rural countryside

- Patients referred for colonoscopy due to complaints related to colon affection

d) Exclusion criteria: These patients were excluded from the study

- Pregnant ladies

- Non-Adults (˂18 years)

- Patients with established liver cirrhosis

- Patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD)

- Patients with known other organic bowel damage, e.g., bowel cancer

- Patients not willing to participate or failed to give consent

|

Figure 2. Study flow chart. IBD; inflammatory bowel diseases.

|

Study subjects.

They are histologically confirmed S. mansoni infected patients (n= 24).

This study was carried out over 18 months, between August 2018 and

January 2020. Four hundred eight-nine colonoscopies were performed

during the study period. Two hundred forty-eight fulfilled our

inclusion criteria, while 241 were excluded being non-inhabitants of

the rural community. Finally, 193 of them gave written informed consent

to participate in the study after explaining the concept, steps,

benefits, and possible adverse events of the investigation. Fifty-five

were excluded from the study due to: Failure to give consent (n=29),

Patients with IBD (n=7), pregnancy (n=1), and the presence of

established liver cirrhosis (n=18) (Figure 2).

Thorough history taking, clinical examination, stool analysis,

abdominal ultrasonography, and pan-colonoscopy evaluated all the

patients.

Confirmation of active Schistosoma infection. Detection of S. mansoni

eggs in stool samples was viewed as the gold standard for the infection

diagnosis. However, it has some limitations in cases of closed (due to

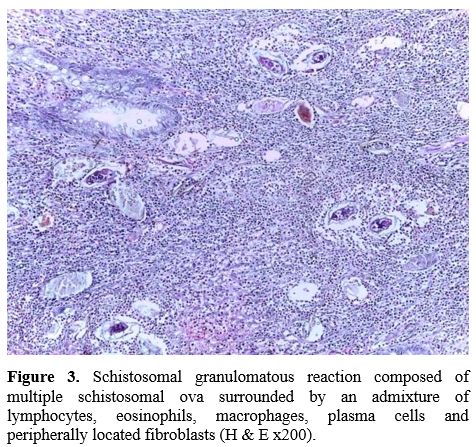

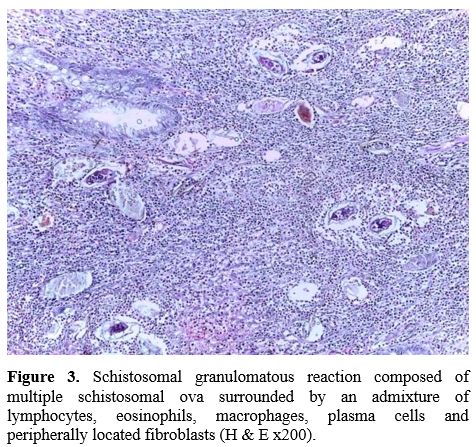

excess fibrosis) or light infections, [11] and that is why active schistosomiasis in this study was defined by detecting the S. mansoni eggs in the histopathology specimens obtained during colonoscopy (Figure 3).

Endoscopic specimens after proper processing were stained with

hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and examined under a high power field.

At least five serial sections were examined before the specimen was

considered negative.

|

Figure 3. Schistosomal

granulomatous reaction composed of multiple schistosomal ova surrounded

by an admixture of lymphocytes, eosinophils, macrophages, plasma cells

and peripherally located fibroblasts (H & E x200).

|

Stool analysis. Stool samples were processed in the laboratory following the Kato–Katz procedure.[12]

Abdominal Ultrasonography.

Done on the day of colonoscopy or 7 days later at the same day of

receiving the histopathology reports. Patients were fasting and

examination with the greyscale ultrasound machine was done before being

examined by colonoscopy to avoid the masking effect of air insufflation

or one week later while patients were fasting. Grading of schistosomal

hepatic periportal fibrosis was carried out following the thickness of

three peripherally located portal tracts into three grades; I (mean

thickness from 3 to 5 mm), II (mean thickness from >5 to 7 mm), and

III (mean thickness from >7 mm).[13]

Colonoscopy examination.

Pan-ileocolonoscopy was planned for all rural residents. The

examination was done following a one-day bowel preparation using the

polyethylene glycol electrolyte solution as 4 sachets (MOVIPREP,

Norgine Limited, UK, or the comparable local products when

unavailable). Patients were prepared with one liter of Moviprep (2

sachets) in the evening before and one liter of Moviprep (2 sachets) in

the early morning of the colonoscopy. The examination was done under

conscious sedation most of the time. Examining the whole colon was

possible with a 100% caecal intubation rate; however, terminal ileum

intubation was possible only in 76.4% (n=19) of patients. The

meticulous colonic examination was done during scope withdrawal, and

mucosal biopsies were taken from the entire colon segments as well as

the morphologically detected lesions.

Rectal snip examination.

Four rectal snips were obtained at the time of colonoscopy. Two were

sent with the histopathology specimens, and 2 were examined under the

microscope to confirm the presence or absence of schistosoma eggs

(Crush biopsy or squash technique).[14,15]

Patient management. All patients with confirmed S. mansoni

infection in this study were treated with praziquantel 600 mg tabs in a

single oral dose given after a heavy (fatty) meal (40 mg/kg body

weight).[16] A second dose was given 4 weeks later to achieve the presumed 95-100% efficacy in parasite eradication.[17] Among our patients, 8 patients were scheduled for follow-up colonoscopy after 3 months from the index colonoscopy.

Data analysis.

The data were analyzed using SPSS, version 23 (SPSS Inc., Chicago,

Illinois, USA). Data were expressed in number (No), percentage (%) mean

(x̅) and standard deviation (SD).

Results

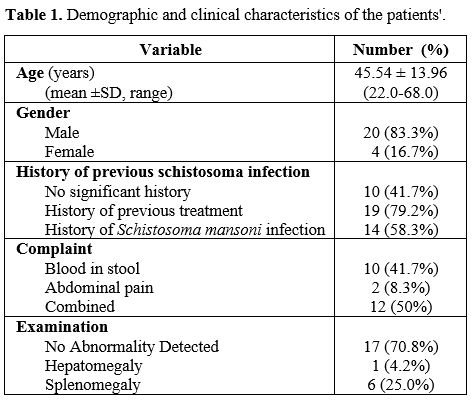

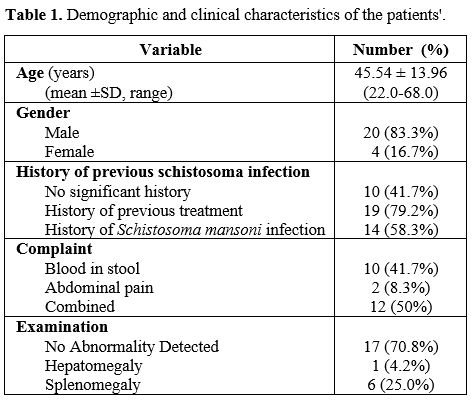

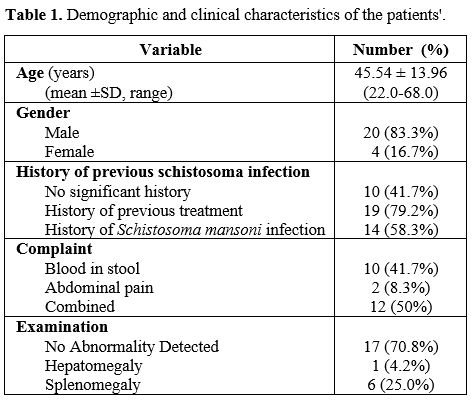

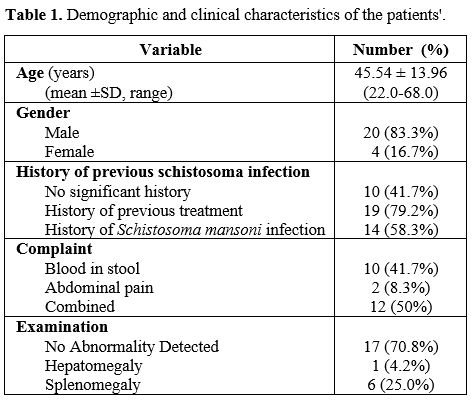

Study populations and clinical characteristics. In this study, 24 out of the 193 symptomatic rural inhabitants examined were infected with active S. mansoni

as confirmed by colonoscopy and biopsies with a prevalence rate of

12.4% (with 95% CI 12.1%, - 25.6%). Patients were diagnosed both in

the Department of Hepatology, Gastroenterology and Infectious Diseases,

Kafrelshiekh University (n=13) and in the endoscopy unit of the

Tropical Medicine Department, Tanta University (n=11). The clinical

characteristics of the cases are shown in Table 1.

|

Table

1. Demographic characteristics for 320 admissions for febrile children

with sickle cell disease.

|

In

this cohort of patients, either the elderly and young adults were

infected; the age range was 22 to 68 years, while the mean age was

45.54 ± 13.96 years, with a high male predominance (83.3%). In this

study, only 11 out of 24 patients (45.8%) were positive for S. mansoni

eggs in their stool samples.

All patients with confirmed active

schistosoma infection in this study were referred to our endoscopy

units due to colon affection manifestations. Overt bleeding with stool

was the predominant manifestation of active S. mansoni infection among the cases either alone or in combination with abdominal pain (Table 1). Of note, 58.3% gave a history of prior S. mansoni infection

confirmed by stool examination at a time point over the last 10 years.

However, 41.7% of the patients, and at the best of their knowledge, did

not report any history of previous schistosomal infection. However,

most of them (n=19, 79.2%) received oral praziquantel treatment; for

their prior S. mansoni

infection (n=14, 58.3%) or during the mass treatment campaigns

implemented by the primary health care. On clinical examination, most

patients (n=17; 70.8%) did not have organomegaly, and 25% had

clinically palpable splenomegaly.

The infected patients'

laboratory data showed that 10 cases (41.7%) had the profile of

microcytic hypo-chromic anemia with hemoglobin levels variable from 8.8

to 10.7 gm/dl with a mean of 9.53±0.71. However, among the 6 patients

(25%) with clinically palpable splenomegaly, the pattern of anemia was

normocytic normochromic with a mean hemoglobin concentration of

10.18±0.34.

Ultrasonic Features.

When these cases were examined by abdominal ultrasonography, the

frequency of organomegaly (splenomegaly and hepatomegaly) increased to

50.0% versus 29.2% on clinical assessment, respectively (Table 2).

|

Table 2. Demographic characteristics for 320 admissions for febrile children

with sickle cell disease.

|

The

most dangerous sequela of intestinal schistosomiasis is the development

of schistosomal hepatic peri-portal fibrosis. Unfortunately, 75.0% of

the infected rural inhabitants had schistosomal hepatic fibrosis,

although it was of grade I (mild form) in half of the cases (50%).

Endoscopic Features. The adult S. mansoni worms

migrate against blood flow to the pelvic venous plexus to lay eggs, and

that is consistent with this study's findings where on colonoscopy, the

recto-sigmoid region was always involved. Furthermore, 16.6% of lesions

showed extension beyond the recto-sigmoid region to involve the entire

left colon (Table 2).

The

most commonly encountered morphologic feature during colonoscopy was

mucosal erythema and congestion (Supplementary video I) either alone (n=7, 29.2%) or associated

with mucosal ulcerations (n=5, 20.8%). Colonic schistosomal polyps

either as the sole manifestation of colonic schistosomiasis (n=3,

12.5%) or in combination with erythema and ulcerations (n=3, 12.5%)

where it is limited to the rectum and sigmoid regions (Figure 4).

An interesting finding of the current study is that 2 patients (8.3%)

were diagnosed with mass-like lesions confused with cancer (Table 2).

|

Figure 4. Demographic characteristics for 320 admissions for febrile children

with sickle cell disease.

|

All

cases with Schistosomal polyps (n=6) were snared successfully during

endoscopy without significant adverse events, while the two patients

with mass-like lesions were referred to surgical resection, and benign

schistosomal nature was histologically confirmed. Colonoscopy follow-up

for 8 patients (polyps n=6, mass-like lesions n=2) showed complete

resolution of the morphologic features associated with schistosomiasis.

Furthermore, surgical margins were free from any apparent lesions. From

the eight patients, multiple rectal and sigmoid biopsies were negative

for schistosomiasis.

Histologic Features. From the histopathologic point of view (Figure 3), all patients showed active S. mansoni

infection features with the living ova surrounded by the characteristic

eosinophilic granuloma containing macrophages, plasma cells, and

lymphocytes and variable degrees of fibrosis (100%). A group of cases

(15.5%) harbored both living and dead S. mansoni

ova. The differentiation between living and dead schistosomal ova was

feasible by noticing the transparency of the eggs, its internal

structures, the shell, the presence of calcification, and granuloma.

Rectal snips directly examined by the crush technique demonstrated the S. mansoni

ova in 21 patients (87.5%). The three patients negative for Schistosoma

ova by rectal snips were the 2 patients with mass-like lesions and one

patient with colonic polyp as the sole finding of colonic

schistosomiasis.

Discussion

Schistosomiasis

has plagued the Egyptian population since the ancient Egyptians. The

disease's prevalence has tremendously decreased but, unfortunately, the

awareness and index of suspicion. As at present, there is only one drug

available for individual treatment, and preventive mass chemotherapy,

and no vaccine, the infection's resurgence is to be feared.[18]

The

spread of schistosomiasis among the rural community inhabitants has

long been investigated in Egyptian[8,9,19] and international

research.[20,21]

The prevalence of S. mansoni

among the symptomatic inhabitants of the rural community in the Middle

and Northern Nile Delta, according to the current study, is 12.4%, a

number lower than the reported rates not only from Egypt but also from

other endemic hot spots in rural communities as in Nigeria (17.8%)[21]

and in Brazil (> 20.5%).[22] Indeed, this rate is lower than the

actual prevalence rates due to focusing on a subset of populations. In

Egypt, among the Nile Delta inhabitants, the same region investigated

in the current study, the prevalence was reported to be 37.7% in the

year 2000.[4] Furthermore, the prevalence rate is lower than the rates

among other high risk groups. Among fishermen in Brazil, it is 13.9%,

while among those of Manzala Lake in Egypt, the prevalence was 24.6%.

The lower prevalence rates reported in the current study can be

explained by health education and mass treatment campaigns practiced in

the country over the last years. In our study, previous Egyptian[8,9]

and international studies,[20,21] males predominate; because they were

more exposed. In our community, males are responsible for the family

earnings most of the time; they have greater employment in agricultural

work and higher contact with water.[23]

Intestinal manifestations

such as diarrhea and colicky pain and dysenteric features may pass

unnoticed, and asymptomatic forms of the infection are more

common.[24] With the infection progression, the chronic sequelae set up

with hepato-splenic affections development, established portal

hypertension occurs, and anemia becomes normochromic.[25] All patients

with confirmed schistosomal infection studied had a history of bleeding

per rectum and/or abdominal pain and consequent hypochromic sideropenic

anemia, and that was why they were referred for pan-colonoscopy.

In addition, 29.2% of them had clinically palpable hepatomegaly and/or

splenomegaly, which points to two crucial issues. First, patients are

symptomatic probably due to a severe infection, and patients had a

neglected ongoing long-term infection, which is why they had

hepato-splenic affection.[25]

Other studies reported different

rates of hepatomegaly and splenomegaly among inhabitants of S. mansoni

high-risk regions both in Egypt[4] and in Tanzania,[26] with

percentages of 22.3%, 20.8%, and 59.70%, 13.73%, respectively. These

figures are different from our figures of 4.2% and 25% due to the

advanced stage of the disease in our cohort with established periportal

fibrosis

We reported, 75% of them had schistosomal periportal

fibrosis, although half (50%) were of the mild form. This rate is much

higher than that of 13.79% found by Mazigo et al. in 2015[26] in

Tanzania. The difference is attributable to both the number and the

nature of participants. We enrolled only 193 high-risk sub-group with

clinical manifestations in our study compared to 1671 individuals

described as permanent inhabitants in their study.[26] Furthermore,

high prevalence rates of schistosomal periportal fibrosis were reported

from different subgroups and geographic locations in Egypt. In Gharbia

Governorate, a prevalence rate of >50% was reported,[19] while

remote governorates, e.g., Ismailia, reported a rate of 43%,[27] and

the pooled data from 5 governorates in lower Egypt reported a rate of

50.3%.[4] However, our higher prevalence rates were due to targeting a

high-risk symptomatic group of small sample size compared to the

general populations in the studies mentioned above.

In fact, in Egypt, hepatic periportal fibrosis is commonly seen with complicated S. mansoni

infection. However, confusion may occur with the presence of liver

cirrhosis.[28] Consequently, following our exclusion of patients with

established liver cirrhosis who may be confused for periportal

fibrosis, we can assume that our patients had schistosomal hepatic

periportal fibrosis.

Zaher et al. in 2011[29] encountered eggs of S. mansoni in

stool samples of 99 persons (0.33%) out of the 30,000 outpatients in

Egypt, while Gad et al. in 2011[30] found stool examination positive

for ova in 25 (9.83%) patients only out of 205 biopsy-positive

schistosomiasis cases in Egypt. Hence, we alarm practitioners in

endemic areas not to rely solely upon stool analysis for diagnosing

colonic schistosomiasis. They can ask for rectal sip examination or

colonoscopy and biopsy due to high positivity rates of 87.5% and 100%,

respectively, compared to 45.8% positivity of stool analysis as

reported in the current study.

Severe chronic intestinal

schistosomiasis may result in colonic or rectal polyposis, stenosis, or

present as an inflammatory mass that may be even confused with

cancer.[31-33] One of the crucial findings of the current study is its

ability to assess the colon both morphologically (by endoscopy) and

pathologically (by histology) to investigate the extent of S. mansoni

induced colon affection. On complete colonoscopy examination, 66.6% of

patients have significant lesions (polyps, ulcers, mass-like lesions)

while 33.4% had mild mucosal erythema and granularity.

Acute and

chronic inflammatory changes could be observed in the same colon

segment of chronic active schistosomal colitis patients.[23] This is

consistent with the findings of the current study, the majority of

patients (66.7%) had mucosal erythema and congestion consistent with

acute active infection, and at the same time, endoscopic features of

chronicity as polyps and masses were also observed.

An interesting

Egyptian study by Gad et al. in 2011[30] reported the prevalence of

colorectal schistosomiasis among patients with different gut symptoms

to be 20.83% by colonoscopy and biopsy. In this study, the authors

biopsied any suspected schistosomal lesion (n= 66) with additional 2

biopsies from the apparently normal rectal mucosa (n=139). The latter

two were examined by crush biopsy, while the other biopsies (average

3-6 per patient) were examined by histopathology. S. mansoni was detected in 205 patients out of 984 patients by colonoscopy.

Endoscopic

findings of the 205 confirmed cases reported by Gad et al.[30] with

schistosomiasis included patchy mucosal congestion (n=39, 19%), patchy

mucosal petechiae (n=11, 5.4%), patchy mucosal erosions +ulcers (n=5,

2.4%), patchy telangiectasia (n=5, 2.4%), sessile mucosal polyps at the

sigmoid colon (n=6,2.2.42%), and apparently normal mucosa (n=139). When

these figures were compared with our reported figures, we reported that

66.6% of patients have significant lesions (polyps, ulcers, mass-like

lesions), which means that our cohort suffered more. Furthermore, we

reported a finding lacking from their cohort; the mass-like lesions

related to schistosomiasis.

In the study of Gad et al.,[30] the

squash technique established the diagnosis of schistosomiasis in all

endoscopically apparently normal cases by demonstrating the

schistosomiasis ova with its characteristic lateral spine. In our

study, the squash technique demonstrated the schistosoma ova in 19

cases. In the two cases with mass-like lesions, the rectal snips were

negative.

In the study of Gad et al.[30] schistosomiasis

affected the rectum (n=25, 12.2%), sigmoid colon (n=26, 12.7%) or

rectum and colon (n=154, 75.1%), while in our study the figures were

12.5%, 25%, and 62.5% respectively. In addition, we reported lesions

beyond the recto-sigmoid in 18.2% of cases. The obvious differences

between our study and that of Gad et al. are probably related to the

nature of patients recruited. Patients of the current study were

high-risk group inhabiting a highly endemic area.

The presence of

colonic schistosomal polyposis does not appear to predispose patients

to significant bowel malignancy development.[33,34] There is agreement

among authors that S. mansoni

is not related to cancer colon. The reported cases of schistosomiasis

in patients with bowel malignancy are no more than epidemiological

association,[33-36] and this is consistent with findings of the current

study.

The high frequency of schistosomal polyps reported in the

current study (25%) is consistent with literature reports of high

frequency of schistosomal colonic polyps in Egypt compared with other

endemic regions like Brazil.[25] These findings of prevalent

schistosomal colon polyps should alarm the endoscopists working in

endemic areas to consider schistosomiasis in the differential diagnosis

of left-sided colonic polyps.[33]

One of the most important

retrospective studies[36] that focused on colonic schistosomiasis was

carried out in Saudi Arabia and recruited 216 patients with

schistosomal colonic disease out of 2458 who had sigmoidoscopy or

colonoscopy over 10 years, diagnosed by endoscopic biopsies (prevalence

rate of 8.8%). The colonoscopic appearance was suggestive of

schistosomiasis in 98 of these patients (45.37%), S. mansoni

ova in stool was detected in only 24 of these 216 patients (11.11%).

The most common histopathological finding in these patients' colonic

biopsies was S. mansoni ova

in the colonic mucosa with no or mild inflammatory cell infiltrates.

The most common symptoms were abdominal pain or distention reported in

84 patients (38.88%). Sixty-five patients (30.09%) had hepatosplenic

schistosomiasis. Eight patients (3.7%) had schistosomal polyps, and two

patients had colonic malignancy in which no association between their

malignancy and S. mansoni

infection was established. The authors concluded that colonoscopic

examination is valuable in colonic schistosomiasis as it can show

characteristic colonic lesions, and colonic biopsies are diagnostic and

correlate with histological findings.

Although we have some

agreements with this study[36] regarding the importance of colonoscopy

in diagnosing colonic schistosomiasis, the low yield of stool ova

detection, and schistosomal's benign nature colonic affection, we have

disagreements on other points. We have a higher frequency rate of

colonic schistosomiasis (12.4% vs. 8.8%); contrary to abdominal pain

and distention, our patients mainly presented with rectal bleeding,

they reported lower prevalence rates of hepato-splenic affection, and

also we had a higher frequency of schistosomal polyps (25% vs 3.7%). We

believe these differences are related to the endemicity of

schistosomiasis in Egypt compared to Saudi Arabia.

The safety of

endoscopic polypectomy for schistosomal colonic polyps among Egyptian

patients has long been documented as early as 1983.[38] This was

emphasized in the current study and in many previous

publications[29,30,36] with minimal risk of adverse events, similar to

the reports for the current study.

The current study showed the

histologic features of active schistosomiasis with the schistosomal

granulomatous reaction composed of multiple schistosomal ova surrounded

by an admixture of lymphocytes, eosinophils, macrophages, plasma cells,

and peripherally located fibroblasts (Figure 1)

and variable degrees of fibrosis. Many studies reported different

activity patterns and fibrosis,[30,36] which seems correlated with the

stage of infection, either acute or chronic.

This study had its

limitations, first, targeting only symptomatic individuals. The aim was

to determine the prevalence among complaining patients to highlight a

daily clinical practice and alarm clinicians in the area for the

persistence of this disease despite the great governmental efforts to

control it. The second limitation was targeting only a specific patient

group, and hence the prevalence rates reported in the current study

cannot be applied to the whole community. Third, the small sample size

of the affected patients; this probably related to targeting only a

specific category of patients. Fourth, it may underestimate the

prevalence among symptomatic rurals due to the exclusion of patients

with IBD and liver cirrhosis patients. However, this was valuable to

achieve the secondary end-points of the study. IBD and liver cirrhosis

are associated with morphological changes in the colon, which may

obscure the S. mansoni induced colon pathology. Furthermore, liver

cirrhosis may confuse the diagnosis of Schistosomal periportal

fibrosis. Furthermore, patients with structural colon damage as IBD and

liver cirrhosis may be excluded from the regular agricultural and

fishing activity in the area.

Conclusions

Out

of the 193 symptomatic rural inhabitants recruited to the current

study, we reported active schistosomiasis in 12.4%, with 66.6% of

patients had significant endoscopic colorectal lesions. All these data

points to the persistent transmission of schistosomiasis in the

Egyptian Nile Delta's rural community. However, the great success in

controlling this infection achieved by governmental efforts over the

past 4 decades with the collaboration of the health care system and

stakeholders should not discontinue screening programs, particularly

for high-risk groups, e.g., farmers, fishermen, etc. If not detected

and effectively treated, these individuals will represent a great

challenge for the diseases' resurgence because they are suitable for

breeding schistosomiasis through water channels and the snail

intermediate host.[3,7]

References

- Hotez PJ, Savioli L, Fenwick A. Neglected tropical

diseases of the Middle East and North Africa: review of their

prevalence, distribution and opportunities of control. PLoS Negl Trop

Dis 2012; 6:e1475-e1482. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0001475 PMid:22389729 PMCid:PMC3289601

- Hotez

PJ, Alvarado M, Basanez M-G, et al. The Global Burden of Disease Study

2010: interpretation and implications for the neglected tropical

diseases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2014; 8:e2865-e2873. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0002496 PMid:24873825 PMCid:PMC4038631

- El

Sharazly BM, Abou Rayia DM, Antonios SN, et al. Current status of

Schistosoma mansoni infection and its snail host in three rural areas

in Gharbia governorate, Egypt. Tanta Med J 2016; 44:141-50. https://doi.org/10.4103/1110-1415.201724

- El-Khoby

T, Galal N, Fenwick A, et al. The epidemiology of schistosomiasis in

Egypt: summary findings in nine governorates. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2000;

62:88-99. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2000.62.88 PMid:10813505

- Barakat

MR, El-Morshedy H, Farghaly A. Human schistosomiasis in the Middle East

and North Africa region. In: McDowell MA, Rafati S, editors. Neglected

tropical diseases − Middle East and North Africa. Wien:

Springer-Verlag; 2014. 23-57. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-7091-1613-5_2

- Olveda DU, Li Y, Olveda RM, et al.. Bilharzia: Pathology, Diagnosis, Management and Control. Trop Med Surg. 2013 20;1(4):135. https://doi.org/10.4172/2329-9088.1000135 PMid:25346933 PMCid:PMC4208666

- Barakat RM. Epidemiology of Schistosomiasis in Egypt: Travel through Time: Review. J Adv Res. 2013;4(5):425-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2012.07.003 PMid:25685449 PMCid:PMC4293883

- Mohamed

AM, el-Sharkawi FM, el-Fiki SA. Prevalence of schistosomiasis among

fishermen of Lake Maryut. Egypt J Bilharz. 1978;5(1-2):85-90.

- Taman

A, El-Tantawy N, Besheer T, et al. Schistosoma mansoni infection in a

fishermen community, the Lake Manzala region-Egypt, As Pac J Trop

Dis,2014; 4(6): 463-468. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2222-1808(14)60607-1

- Haggag

AA, Rabiee A, AbdElaziz KM, et al. Mapping of Schistosoma mansoni in

the Nile Delta, Egypt: Assessment of the prevalence by the circulating

cathodic antigen urine assay. Acta Trop. 2017;167:9-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2016.11.038 PMid:27965144

- Doenhoff

MJ, Chiodini PL, Hamilton JV. Specific and sensitive diagnosis of

schistosome infection: can it be done with antibodies? Trends Parasitol

2004; 20:35-39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2003.10.019 PMid:14700588

- Katz

N, Chaves A, Pellegrino J. A simple device for quantitative stool thick

smear technique in Schistosomiasis mansoni. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo

1972; 14:397-400.

- Abdel-Wahab MF, Esmat

G, Farrag A, et al. Grading of hepatic schistosomiasis by the use of

ultrasonography. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;46(4):403-8. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.1992.46.403 PMid:1575286

- Harries

AD, Speare R. Rectal snips in the diagnosis of hepatosplenic

schistosomiasis, Transactions of The Royal Society of Tropical Medicine

and Hygiene, 1988; 82(5): 720. https://doi.org/10.1016/0035-9203(88)90213-1

- Shipkey FH. Squash technique for rapid identification of schistosoma ova. Ann Saudi Med. 1986;6:71-2. https://doi.org/10.5144/0256-4947.1986.71 PMid:21164245

- Gray DJ, Ross AG, Li YS, et al. diagnosis and management of schistosomiasis. BMJ. 2011 17;342:d2651. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d2651 PMid:21586478 PMCid:PMC3230106

- Li

Y, Sleigh AC, Williams GM, et al. Measuring exposure to Schistosoma

japonicum in China. III. Activity diaries, snail and human infection,

transmission ecology and options for control. Acta Trop 2000;75:279-89.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-706X(00)00056-5

- Othman AA, Soliman RH. Schistosomiasis in Egypt: A never-ending story? Acta Trop. 2015; 148:179-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2015.04.016 PMid:25959770

- El-Hawey

AM, Amer MM, Abdel Rahman AH, et al. The epidemiology of

schistosomiasis in Egypt: Gharbia Governorate. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2000;

62:42-48. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2000.62.42 PMid:10813499

- Melo,

Andrea Gomes Santana de, Irmão, José Jenivaldo de Melo, Jeraldo,

Verónica de Lourdes Sierpe, et al. Schistosomiasis mansoni in families

of fishing workers of endemic area of Alagoas. Escola Anna Nery, 2019;

23(1), e20180150. https://doi.org/10.1590/2177-9465-ean-2018-0150

- Dawaki

S, Al-Mekhlafi HM, Ithoi I, et al. PREVALENCE AND RISK FACTORS OF

SCHISTOSOMIASIS AMONG HAUSA COMMUNITIES IN KANO STATE, NIGERIA. Rev

Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2016 11;58:54. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1678-9946201658054 PMid:27410914 PMCid:PMC4964323

- Conceição

MJ, Carlôto AE, de Melo EV, et al. Prevalence and Morbidity Data on

Schistosoma mansoni Infection in Two Rural Areas of Jequitinhonha and

Rio Doce Valleys in Minas Gerais, Brazil. ISRN Parasitol. 2013

19;2013:715195. https://doi.org/10.5402/2013/715195 PMid:27335859 PMCid:PMC4890927

- El

Malatatwy A., El Habashy A., LechineN.,et al. Selective population

chemotherapy among school children in Beheira Governate: the

UNICEF/Arab Republic of Egypt/WHO Schistosomiasis Contrl Project. Bull

World Health Organization. 1992;70:47-56.

- Elbaz T, Esmat G. Hepatic and intestinal schistosomiasis: review. J Adv Res. 2013;4(5):445-52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2012.12.001 PMid:25685451 PMCid:PMC4293886

- Da Silva LC, Chieffi PP, Carrilho FJ.Schistosomiasis mansoni -- clinical features. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;28(1):30-9. https://doi.org/10.1157/13070382 PMid:15691467

- Mazigo

HD, Dunne DW, Morona D, et al. Periportal fibrosis, liver and spleen

sizes among S. mansoni mono or co-infected individuals with human

immunodeficiency virus-1 in fishing villages along Lake Victoria

shores, North-Western, Tanzania. Parasit Vectors. 2015 7;8:260. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-015-0876-4 PMid:25948238 PMCid:PMC4424565

- Nooman

ZM, Hasan AH, Waheeb Y, et al. The epidemiology of schistosomiasis in

Egypt: Ismailia governorate. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;62(2 Suppl):35-41.

https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2000.62.35 PMid:10813498

- Abdel-Kader

S, Amin M, Hamdy H, et al. Causes of minimal hepatic periportal

fibrosis present in Egypt. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 1997;27(3):919‐924.

- Zaher

T, Abdul-Fattah M, Ibrahim A, et al. Current Status of Schistosomiasis

in Egypt: Parasitologic and Endoscopic Study in Sharqia Governorate.

Afro-Egypt J Infect Endem Dis 2011; 1(1):9-11. https://doi.org/10.21608/aeji.2011.8754

- Gad

YZ, Ahmad NA, El-Desoky I, et al. Colorectal schistosomiasis: Is it

still endemic in delta Egypt, early in the third millennium?. Trop

Parasitol 2011;1:108-10. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-5070.86948 PMid:23508170 PMCid:PMC3593472

- Ross AGP, Bartley PB, Sleigh AC, et al. schistosomiasis. N Eng J Med 2002;346:1212-9. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra012396 PMid:11961151

- Gryseels B, Polman K, Clerinx J, et al. Human schistosomiasis. Lancet 2006; 368:1106-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69440-3

- Elbatee HE, Emara MH, Zaghloul MS, et al. Huge bilharzial polyp mimicking colon cancer. JGH Open. 2019 12;4(2):280-283. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgh3.12181 PMid:32280778 PMCid:PMC7144792

- Barsoum H. Cancer in Egypt: its incidence and clinical forms. Acta Uni Intern Con Can. 1953;9:241-250.

- Salim

HO, Hamid HK, Mekki SO, et al. Colorectal carcinoma associated with

schistosomiasis: a possible causal relationship. World J Surg Oncol.

2010;8:68. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7819-8-68 PMid:20704754 PMCid:PMC2928231

- Mohamed AR, al Karawi M, Yasawy MI. Schistosomal colonic disease. Gut. 1990;31(4):439-42. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.31.4.439 PMid:2110925 PMCid:PMC1378420

- Emara

MH, Ahmed MH, Mahros AM, et al. No part of the colon is immune from

large Bilharzial polyps. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol.

2020;32(7):896‐897. https://doi.org/10.1097/MEG.0000000000001727 PMid:32472818

- Bessa SM, Helmy I, El-Kharadly Y. Colorectal schistosomiasis. Endoscopic polypectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1983;26(12):772-4.) https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02554745 PMid:6641458

[TOP]