Magda Zanelli1, Loredana Ruggeri2, Francesca Sanguedolce3, Maurizio Zizzo4,5,*, Giovanni Martino2, Angelo Genua6 and Stefano Ascani7.

1 Pathology Unit, Azienda Unità Sanitaria Locale-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, 42122 Reggio Emilia, Italy.

2 Hematology Unit, CREO, Azienda Ospedaliera di Perugia, University of Perugia, 06123 Perugia, Italy.

3 Pathology Unit, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria-Ospedali Riuniti di Foggia, 71122 Foggia, Italy.

4 Surgical Oncology Unit, Azienda Unità Sanitaria Locale-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, 42122 Reggio Emilia, Italy.

5 Clinical and Experimental Medicine PhD Program, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, 41121 Modena, Italy.

6 Oncohematology Unit, Azienda Ospedaliera S. Maria di Terni, University of Perugia, 05100 Terni, Italy.

7 Pathology Unit, Azienda Ospedaliera S. Maria di Terni, University of Perugia, 05100 Terni, Italy.

Correspondence to: Maurizio Zizzo, Surgical Oncology Unit, Azienda

Unità Sanitaria Locale-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Viale Risorgimento, 80,

42123 Reggio Emilia, Italy. Tel: +39-0522-296372, fax: +39-0522-295779.

E-mail:

zizzomaurizio@gmail.com

Published: March 1, 2021

Received: January 30, 2021

Accepted: February 14, 2021

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2021, 13(1): e2021026 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2021.026

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

To the editor.

We read with great interest the paper by Urio et al. reporting on prevalence and factors associated with Human Parvovirus B19 infection in sickle cell patients hospitalized in Tanzania.[1] People with frequent episodes of hemolytic anemia, including sickle cell disease, are at increased risk of Parvovirus B19 infection as well as immunocompromised patients.[1]

We

report the case of a 50-year-old woman with a few years history of

common variable immunodeficiency (CVID), presenting with profound

asthenia. The patient had previously declined immunoglobulin therapy

due to the absence of infective episodes. Few days before admission,

she had a fever following the meningococcal vaccine. On admission, the

patient was afebrile. Splenomegaly (16 cm in maximum diameter) was

present in the absence of lymphadenopathy. Laboratory tests revealed

anemia (Hb 7.5 g/dl) with low reticulocyte count (0.1%, normal adult

range 0.5% to 2.5%). Serum electrophoresis confirmed

hypogammaglobulinemia (IgG 519 mg/dl, normal range 700-1600 mg/dl; IgA

46 mg/dl, normal range 70-400; IgM 20 mg/dl, normal range 40-280

mg/dl). Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level was elevated (594 UI/L).

Coombs test was negative. B12 vitamin and folate were within normal

values. Serologic tests for Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C virus, Human

Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), and Parvovirus B19 were negative, as well as rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibodies.

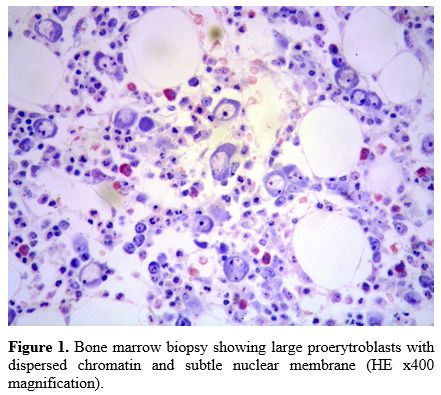

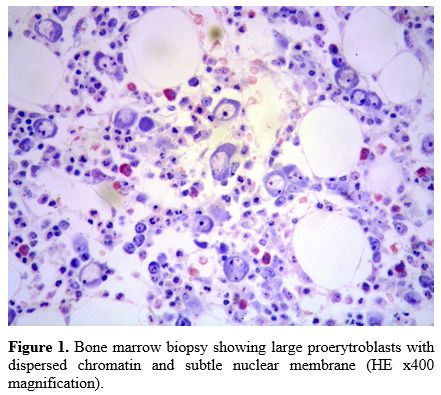

Bone

marrow biopsy showed a normocellular marrow with a reduced erythroid

lineage relative to the overall intact granulopoiesis. The

erythropoiesis was almost completely made up of large-sized

proerithroblasts (so-called megaloblasts) with vesicular chromatin and

a subtle nuclear membrane (Figure 1).

Megakaryocytes were slightly increased in number with nuclear

lobulation defects. Cytogenetic analysis revealed a normal karyotype.

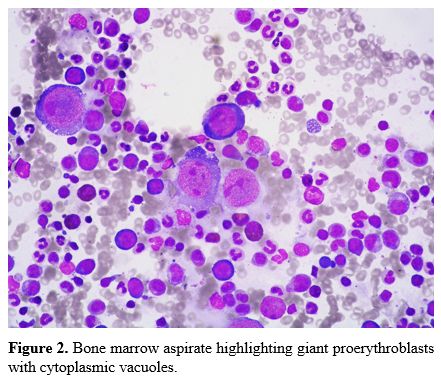

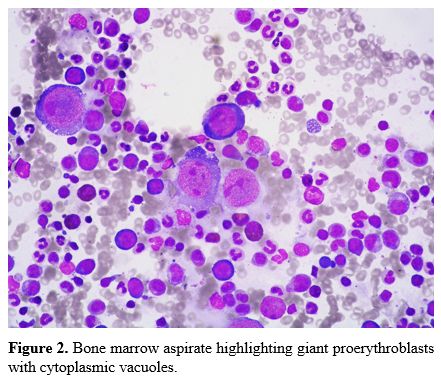

Bone marrow aspirate confirmed the presence of giant proerythroblasts

with cytoplasmic vacuoles (Figure 2). The marrow findings were suggestive of Parvovirus B19 infection. In our patient, Parvovirus B19 serology was negative. However, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detected Parvovirus

B19 DNA (556,936 viral copies) on peripheral blood. Prompt treatment

with intravenous immunoglobulins (400/mg/kg for five days) was started

with progressive anemia resolution and a marked decrease of viral DNA

copies. Because of the infective episode, treatment with subcutaneous

immunoglobulins was continued indefinitely. The patient is well, with

no other infective episode at about three years from Parvovirus B19 infection.

|

Figure

1. Bone marrow biopsy showing large proerytroblasts with dispersed

chromatin and subtle nuclear membrane (HE x400 magnification). |

|

Figure

2. Bone marrow aspirate highlighting giant proerythroblasts with cytoplasmic vacuoles. |

Human Parvovirus B19 (HPV-B19) is the only member of the Parvoviridae family known to be pathologic in humans.[2] It is classified as a member of the Erythroparvovirus

genus due to its unique high tropism to red blood cell precursors,

leading to temporary bone marrow infection and transient erythropoiesis

arrest.[3] The clinical manifestations of HPV-B19

infection depend on the host's age and hematological and immunological

status. In adults, the viremic period is generally characterized by low

hemoglobin level, with reticulocytes disappearance associated with

fever, arthralgia, and malaise. The clinical manifestation is usually

self-limited in healthy individuals developing specific anti-virus

antibodies. Sickle cell disease patients, as reported in the paper by

Urio et al.,[1] have a high risk of infection due to

the increase in red blood cells precursor division, that sickle cell

patients have to compensate for the deficiency of circulating red blood

cells. In the setting of immunodeficiency, as in CVID patients unable

to develop a specific immune response neutralizing the virus, there is

a persistent viremia, and the clinical manifestation is usually

aplastic anemia, although cases presenting as polyarticular arthritis

are reported.[2,4,5] Acute Parvovirus

B19 infection should be suspected in patients with immunologic diseases

presenting with reticulocytopenic anemia. It is worth mentioning that

in immunocompromised individuals, as in our patient, Parvovirus B19 serology can be negative, because of the reduced capacity to develop an antibody response.[5] In these patients, PCR analysis of Parvovirus

B19 is essential to achieve the correct diagnosis and set the

appropriate therapy. Immunoglobulin replacement could result in

clearance of viremia, as it was in our patient.[6]

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All

procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in

accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or

national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and

its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

The patient signed an informed consent form and agreed to publication.

References

- Urio F, George H, Tluway F, Nyambo TB, Mmbando BP,

Makani J. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Human Parvovirus B19

Infection in Sickle Cell Patients Hospitalized in Tanzania. Mediterr J

Hematol Infect Dis. 2019;11(1):e2019054. https://doi.org/10.4084/mjhid.2019.054 PMid:31528320 PMCid:PMC6736168

- Peterlana

D.; Puccetti A.; Corrocher R.; Lunardi C. Serologic and molecular

detection of human Parvovirus B19 infection. Clin Chim Acta 2006, 372,

14-23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2006.04.018 PMid:16765338

- Heegaard H.D.; Brown K.E. Human parvovirus B19. Clin Microbiol Rev 2002, 15, 485-505. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.15.3.485-505.2002 PMid:12097253 PMCid:PMC118081

- Adams

S.T.M.; Schmidt K.M.; Cost M.K.; Marshall G.S. Common variable

immunodeficiency presenting with persistent parvovirus B19 infection.

Pediatrics 2012, 130, e1711-5. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2556 PMid:23129076

- Ruiz

Gutiérrez L.; Albarrán F.; Moruno H.; Cuende E. Parvovirus B19 chronic

monoarthritis in a patient with common variable immunodeficiency.

Reumatol Clin 2015, 11, 56-59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reuma.2014.07.001 PMid:25441493

- Chuhjo

T.; Nakao S.; Matsuda T. Successful treatment of persistent erythroid

aplasia caused by Parvovirus B19 infection in a patient with common

variable immunodeficiency with low-dose immunoglobulin. Am J Hematol

1999, 60, 222-224. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1096-8652(199903)60:3<222::AID-AJH9>3.0.CO;2-K

[TOP]