Hussam Tabaja1, Joya-Rita Hindy1 and Souha S. Kanj2.

1 Mayo Clinic, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Rochester, Minnesota, USA.

2

American University of Beirut Medical Center, Division of Infectious

Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Beirut, Lebanon.

Correspondence to:

Souha S. Kanj, MD, FACP, FIDSA, FRCP, FESCMID, FECMM. Professor of

Medicine. Head, Division of Infectious Diseases, Chairperson, Infection

Control Program, American University of Beirut Medical Center, P.O. Box

11-0236 Riad El Solh 1107 2020, Beirut, Lebanon. Tel: 961-1-350000;

Fax: 961-1-370814. E-mail:

sk11@aub.edu.lb

Published: September 1, 2021

Received: March 3, 2021

Accepted: August 4, 2021

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2021, 13(1): e2021050 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2021.050

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Available

data suggest a high burden of methicillin-resistant staphylococcus

aureus (MRSA) in Arab countries of the Middle East and North Africa

(MENA). To review the MRSA rates and molecular epidemiology in this

region, we used PubMed search engine to identify relative articles

published from January 2005 to December 2019. Great heterogeneity in

reported rates was expectedly seen. Nasal MRSA colonization ranged from

2%-16% in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), 1-9% in the Levant, and

0.2%-9% in North African Arab states. Infective MRSA rates ranged from

9%-38% in GCC, 28%-67% in the Levant, and 28%-57% in North African

states. Studies demonstrated a wide clonal diversity in the MENA. The

most common molecular types belonged to 5 clonal complexes (CC) known

to spread worldwide: CC5, CC8, CC22, CC30, and CC80. The most prevalent

strains had genotypes related to the European community-acquired MRSA

(CA-MRSA), Brazilian/Hungarian hospital-acquired MRSA (HA-MRSA),

UK-EMRSA-15 HA-MRSA, and USA300 CA-MRSA. Finally, significant

antimicrobial resistance was seen in the region with variation in

patterns depending on location and clonal type. For a more accurate

assessment of MRSA epidemiology and burden, the Arab countries need to

implement national surveillance systems.

|

Introduction

The

last few decades have witnessed an increasing interest in the molecular

epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

Various techniques have been utilized to decipher the MRSA genotype,

which could provide insight into a strain's resistance capacity and

virulence. It also provides insight into their origin of spread and

helps implement proper infection control measures.[1]

To

date, MRSA is the most frequently identified antibiotic-resistant

microbe in many regions, including East Asia, the Middle East, North

Africa, Europe, and the Americas.[2] Available data suggest a high burden of MRSA in Arab countries of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA).[3,4]

However, the Arab world lacks both regional and national surveillance

systems. Instead, the current literature is derived from fragmented

single-centered research. Moreover, no review summarizing such findings

is yet available. Therefore, the purpose of our paper is to examine the

current literature on the epidemiology of MRSA in Arab countries of the

MENA region.

Definitions

The Middle East and North African Region:

According to the World Bank, the MENA region comprises 21 member

states. The Arab member states include the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

(KSA), Unites Arab Emirates (UAE), Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain, Oman, Yemen,

Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Palestine (west bank and Gaza strip), Iraq,

Egypt, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, Yemen, and Libya.[5] MRSA molecular typing techniques:

Currently, there are four molecular typing techniques, including

pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), Multilocus sequence typing

(MLST), staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) typing, and S.

aureus protein A gene (spa) typing. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis:

It is considered the reference standard for MRSA typing. Uses

restriction enzyme SmaI to digest purified chromosomal DNA followed by

agarose gel electrophoresis. A unique pattern is created and analyzed

using the Dice coefficient and unweighted pari-group matching analysis

(UPGMA). Thus, it is the most discriminative method and the best for

investigating hospital outbreaks. Nonetheless, efforts to harmonize

PFGE protocols have failed, which hinders inter-laboratory

comparability.[1] Therefore, it is not useful when comparing isolates from different centers.[6] Multilocus sequence:

It is based on sequence analysis of 7 housekeeping genes (arcC, aroE,

glpF, gmk, pta, tpi, yqiL). Each unique sequence within a gene is

designated as an allele. When combined, the 7-allele pattern behaves as

an allelic profile or sequence type (ST) that defines the MRSA

isolate. For example, all isolates with the allelic profile

7-6-1-5-8-8-6 are clones and this sequence is identified as ST5.

However, this method is laborious and time-consuming.[1] A database for MLST typed isolates identified and reported globally exists through http://www.pubmlst.org. Staphylococcal Cassette Chromosome mec:

SCCmec is a mobile genetic element that harbors mecA gene. Different

typing methods exist, utilizing polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

technology. There are five main types, SCCmec I to V,1 but overall, 13

types have been reported (type I-XIII), some of which have

subvariants.[7]Staphylococcus aureus Protein A Gene Typing:

This is a single-locus DNA sequence typing of the polymorphic region X

of spa gene. The typing reveals a specific pattern of repeats which is

then used to deduce the spa type. It is simpler than the tedious MLST

typing. It has good discriminatory power that lies between PFGE and

MLST. Although individual laboratories use "in-house" sequencing

platforms, a dedicated software (Ridom StaphType software) that

analyzes sequencing patterns from different laboratories exists and is

accessible to the public. This software helps ensure interlaboratory

comparability. A laboratory's typing data can be uploaded and

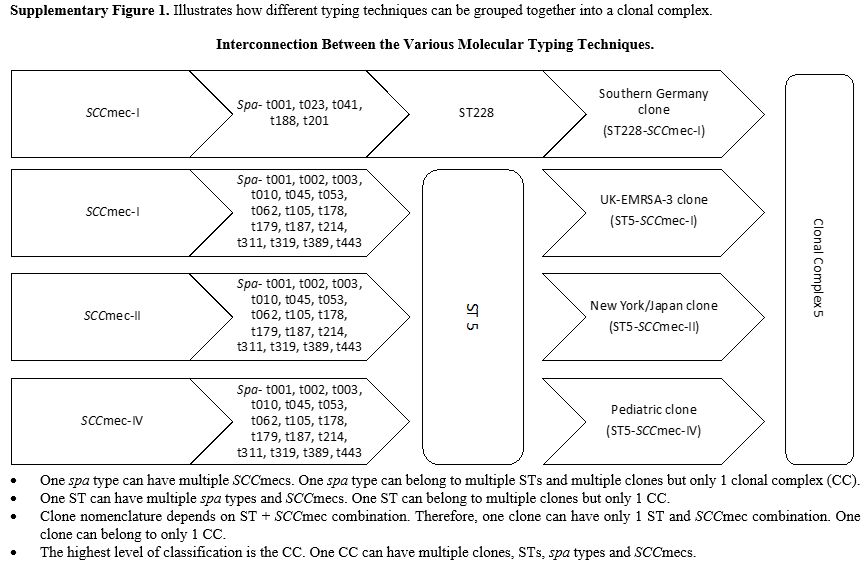

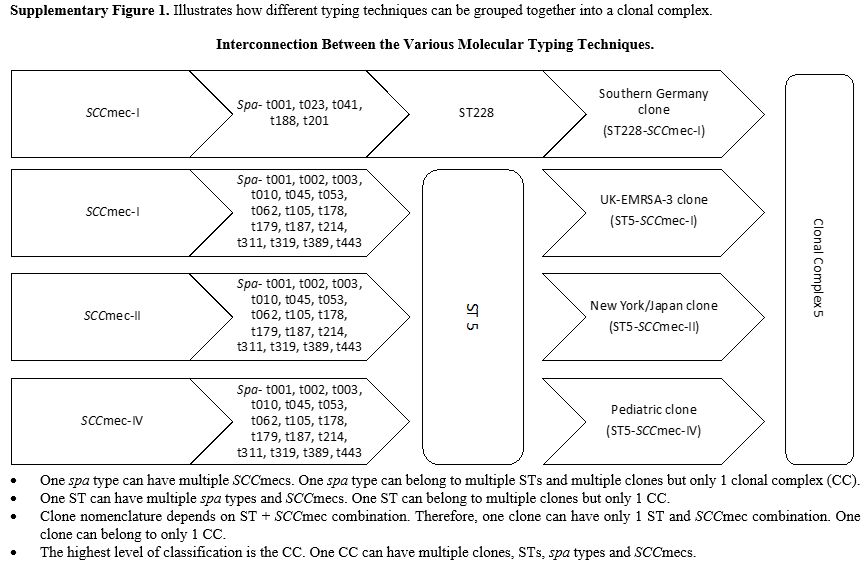

synchronized into the database via a central server available at http://www.spaserver.ridom.de. The database currently has 20,056 spa types reported, representing 444,798 total strains from 146 countries.[1] Clonal Complex:

The primary method of determining clonal complex (CC) is based on MLST.

Individual isolates with an identical sequence in at least 5 out of 7

housekeeping genes are grouped into a CC. The ancestor of a CC is the

ST with the highest single-locus variants. Therefore, each ST will

belong to a single CC, but each CC can have several STs with five

identical housekeeping genes. For example, ST228 and ST5 both belong to

CC5.[1]Due

to a higher discriminatory power, several spa types can belong to the

same ST. A unique spa-type can be shared among several STs but can

belong to only 1 CC. Therefore, clustering analysis based on spa typing

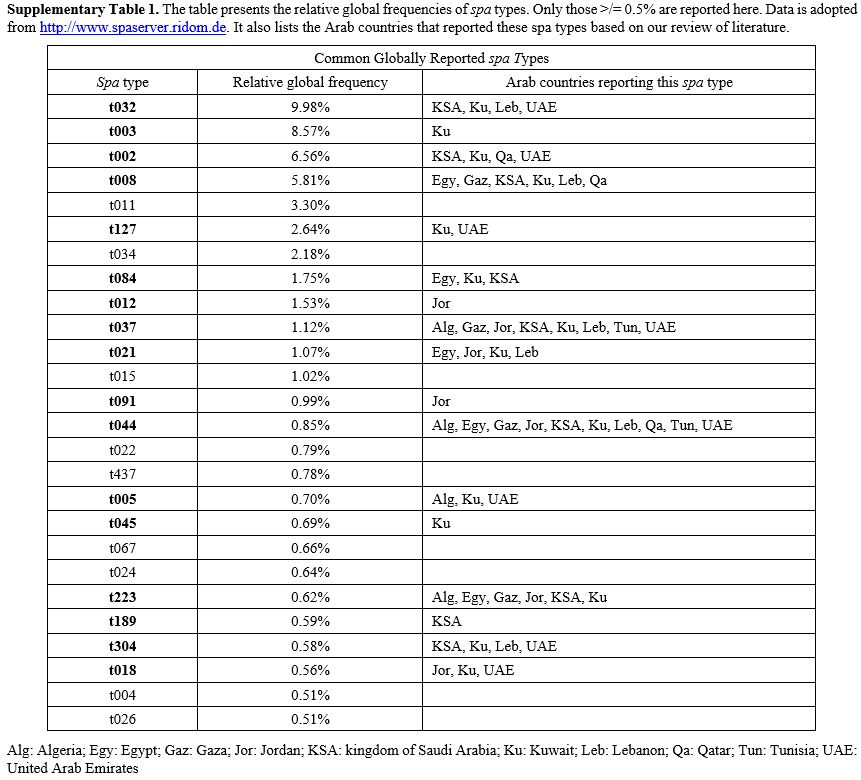

is also feasible (i.e., spa-CC). Supplementary Table 1 reports the relative global frequencies of common spa types. MRSA Clone Nomenclature:

The nomenclature of MRSA strains is determined by the combination of

ST and SCCmec type. For example, ST239-SCCmec-III is colloquially

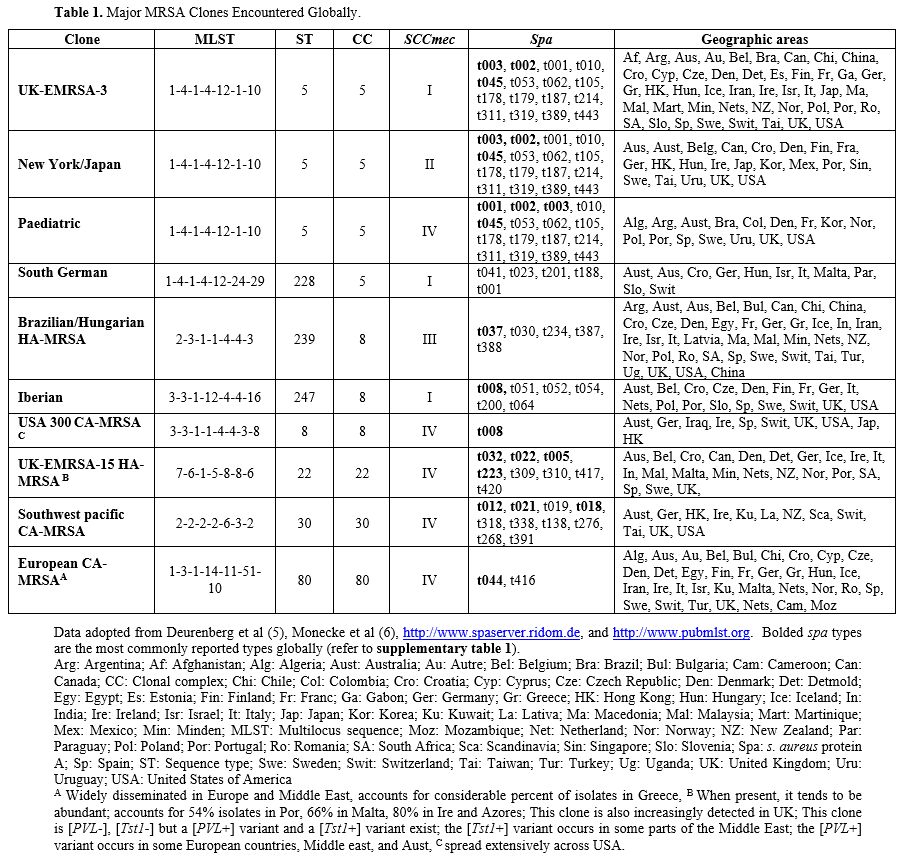

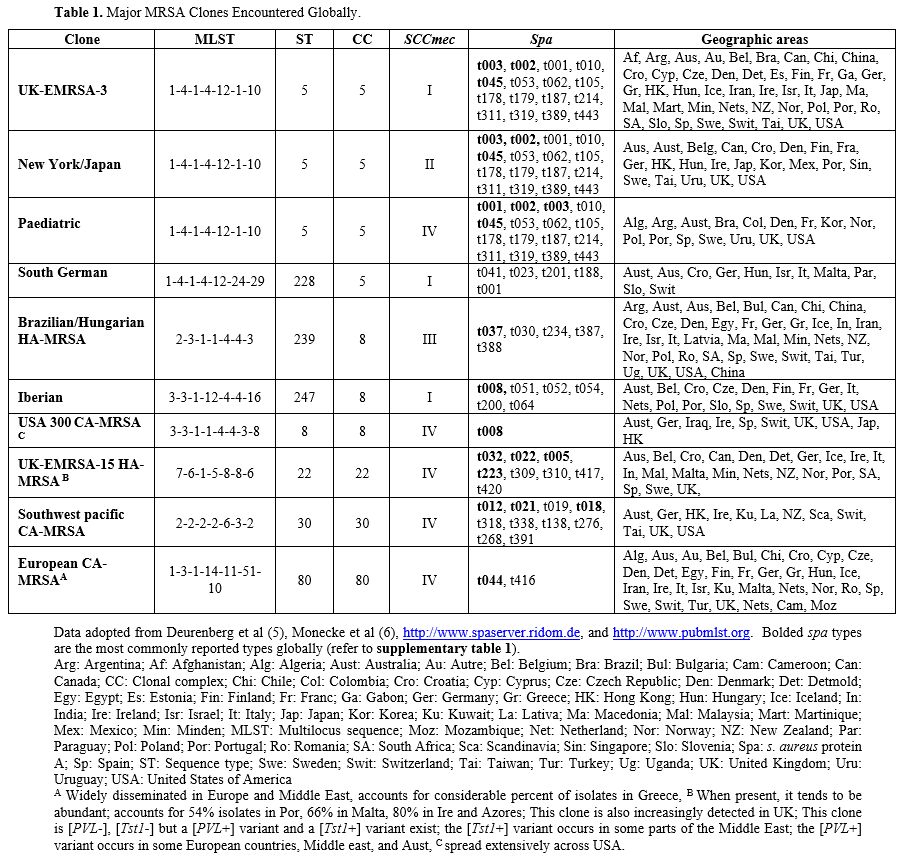

known as Brazilian/Hungarian clone. Table 1 lists some of the major clones identified globally. Some clones can have more than 1 colloquial name.

|

Table 1. Major MRSA Clones Encountered Globally.

|

For a more detailed description of MRSA molecular typing, we refer our readers to a publication by Deurenberg et al..[1] Additionally, a comprehensive guide describing the different MRSA clones is available.[8] Finally, Supplementary Figure 1 illustrates the interconnection of different typing methods.Panton-valentine leucocidin (PVL) and toxic shock syndrome-toxin 1 (tst1): The lukF/S-PV and TST genes encode PVL and Tst1, respectively, which are virulence factors found in MRSA.[9] More

specifically, [PVL+] strains can cause leukocyte destruction and tissue

necrosis and are frequently associated with skin and soft tissue

infections and necrotizing pneumonia.[10] PVL is commonly found in CA-MRSA strains and rarely present in HA-MRSA strains.[8] Community-acquired MRSA (CA-MRSA) vs. Hospital-acquired MRSA (HA-MRSA): Distinguishing between CA-MRSA and HA-MRSA has traditionally been based on genetic makeup.[1]

CA-MRSA is typically associated with SCCmec types IV/V while HA-MRSA is

associated with types I/II/III. However, CA-MRSA carrying SCCmec type

I, II, and III and HA-MRSA carrying type IV have been identified

questioning the distinction based on SCCmec alone.[1] Alternatively,

MRSA can be classified by epidemiological criteria. The epidemiologic

definition of CA-MRSA is any strain isolated in an outpatient setting

or within 48 hours of admission in a patient with no prior history of

MRSA infection or colonization, no permanent invasive medical devices,

and none of the following risk factors within the past year:

hemodialysis, surgery, hospitalization, residence in a long-term care

facility.[1,11] Strains not fitting

this definition are considered HA-MRSA. Nonetheless, we now know that

both genotypes can be acquired regardless of risk factors.[1]

Therefore, the better practice would be to use epidemiological criteria

to label isolates as community-onset (CO-MRSA) versus hospital-onset

(HO-MRSA). For

the sake of our review, we use the genetic makeup to identify CA-MRSA

or HA-MRSA and, when provided, the epidemiological criteria to

distinguish CO-MRSA from HO-MRSA. Antimicrobial Susceptibilities:

We reviewed reported susceptibility rates against rifampin, fusidic

acid, clindamycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX),

ciprofloxacin, tetracycline, erythromycin, vancomycin, linezolid,

teicoplanin, daptomycin, mupirocin, and gentamicin.

Methodology

We

used the PubMed search engine to identify articles published from

January 2005 to June 2019. We selected 13 out of the 18 Arab countries

listed in section the Middle East and North African Region,

geographically spread across the MENA region. The area was subdivided

into the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), which includes KSA, Kuwait,

UAE, Qatar, Bahrain and Oman; the Levant region, which includes

Lebanon, Palestine, Jordan, and Iraq; and the North African region,

which includes Egypt, Algeria, and Tunisia. For our search we used the

following terms: "Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus", "Saudi

Arabia", "Kuwait", "United Arab Emirates", "Oman", "Qatar", "Bahrain",

"Iraq", "Lebanon", "Palestine", "Gaza strip", "West bank", "Jordan",

"Syria", "Egypt", "Algeria", "Tunisia". Our search retrieved 134

articles. We excluded articles that lacked clear methodology and

articles written in languages other than Arabic and English. We also

disregarded articles that were not accessible unless all relevant

information was clearly provided in the abstract. Finally, we included

20 articles from KSA, 8 from Kuwait, 5 from UAE, 2 from Qatar, 1 from

Bahrain, 7 from Lebanon, 5 from Jordan, 3 from Gaza, 1 from West Bank,

10 from Algeria, 5 from Tunisia, and 7 from Egypt.

Results

MRSA colonization in the MENA region:

MRSA Nasal Carriage:

Subjects with MRSA isolated from nasal/pharyngeal swabs without

symptoms attributed to MRSA infection are considered colonized. We

report MRSA carriage rate as a percent of total nasal/pharyngeal swabs

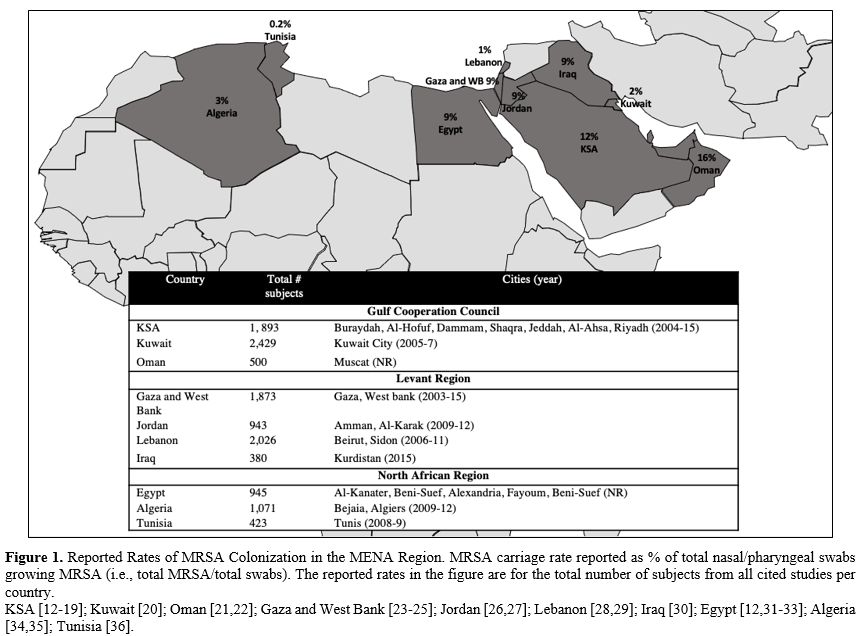

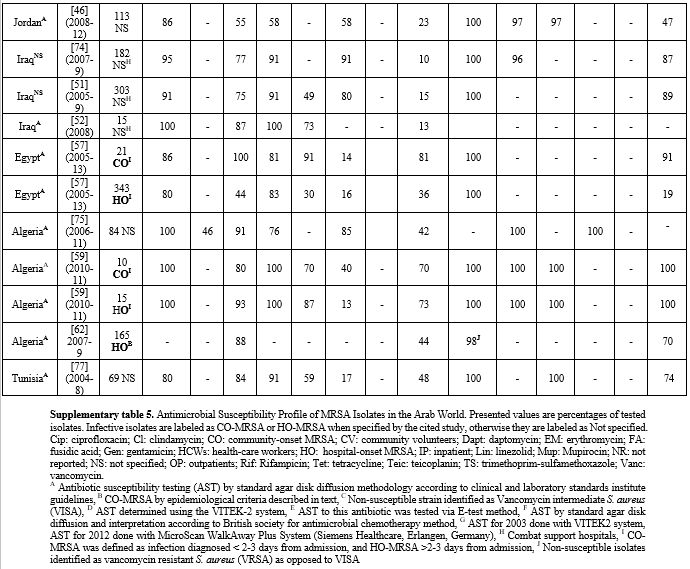

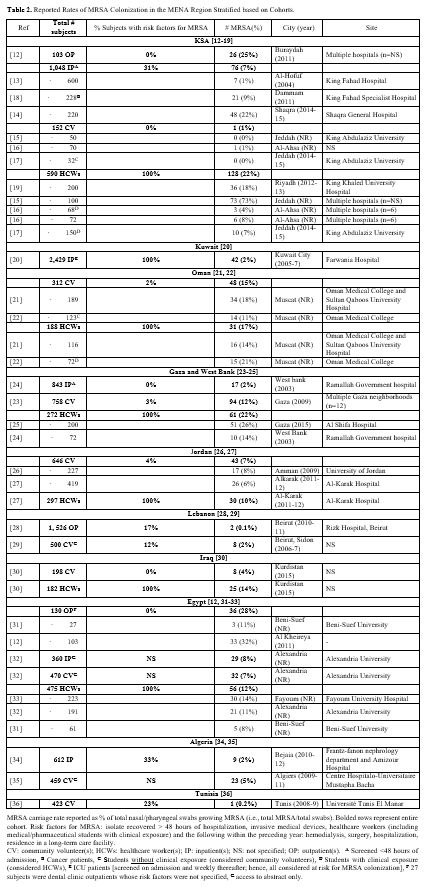

growing MRSA (i.e., total MRSA/total swabs). Figure 1 provides the MRSA carriage rate of total subjects combined from all studies per country. Table 2 lists rates stratified according to four cohorts (outpatients, inpatients, healthy volunteers, and HCWs).

|

Figure 1. Reported Rates of MRSA

Colonization in the MENA Region. MRSA carriage rate reported as % of

total nasal/pharyngeal swabs growing MRSA (i.e., total MRSA/total

swabs). The reported rates in the figure are for the total number of

subjects from all cited studies per country.

KSA [12-19]; Kuwait [20]; Oman [21,22]; Gaza and West Bank [23-25]; Jordan [26,27]; Lebanon [28,29]; Iraq [30]; Egypt [12,31-33]; Algeria [34,35]; Tunisia [36]. |

|

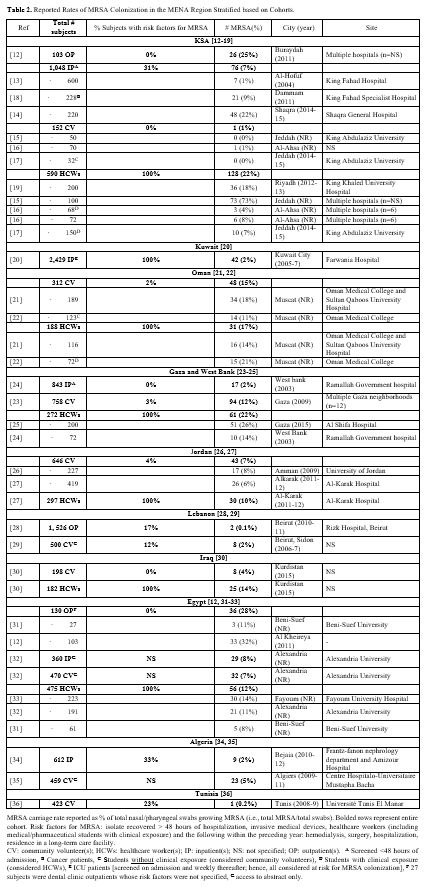

Table 2. Reported Rates of MRSA Colonization in the MENA Region Stratified based on Cohorts. |

When combining all subjects reported per country, the colonization rates ranged from 2%-16% in GCC,[12-22] 1-9% in Levant,[23-30] and 0.2%-9% in North African Arab states.[12,31-36]

In the GCC, reported rates were overall higher in KSA and Oman compared

to Kuwait. In the Levant and North Africa, Lebanon and Tunisia had very

low rates. Several

factors may account for the difference in reported rates between

studies. These include the difference in study cohorts (i.e., high risk

vs. low risk for colonization), the difference in the study period, and

the difference in local factors of the study site (i.e.,

resource-limited vs. resource-rich city or center). It is difficult

through our review to determine which factors explain the observed

difference in rates. The cited studies from Lebanon were limited to

outpatients and community volunteers only as opposed to Gaza, Jordan,

and Iraq, where some studies included HCWs. Nonetheless, even when

comparing similar groups, the rates in Lebanon remained lower. This is

true for Beirut and Sidon, 2 heavily populated cities in Lebanon.[28,29]

It is also unclear why Kuwait in GCC and Tunisia in North Africa had

lower rates than neighboring states. The study from the city of Kuwait

included 2,429 intensive care patients screened on admission and weekly

thereafter, yet only 2% had MRSA colonization.[20] In Tunisia, only 0.2% of 423 community volunteers carried MRSA,[36] while rates in similar groups reached 5% in Algeria and 7% in Egypt.[12,31-35] Moreover,

the reported rates of MRSA carriage varied widely between centers and

communities within the same country. Here again, the difference in

rates may be driven by the aforementioned factors. Perhaps the

interplay between varying environmental and social factors across a

county could explain why certain areas serve as pockets for higher

prevalence. In the healthcare setting, discrepancies in rates between

hospitals might be driven by differences in the type of patients served

(i.e., high acquity versus low acuity hospitals) and the institutional infection

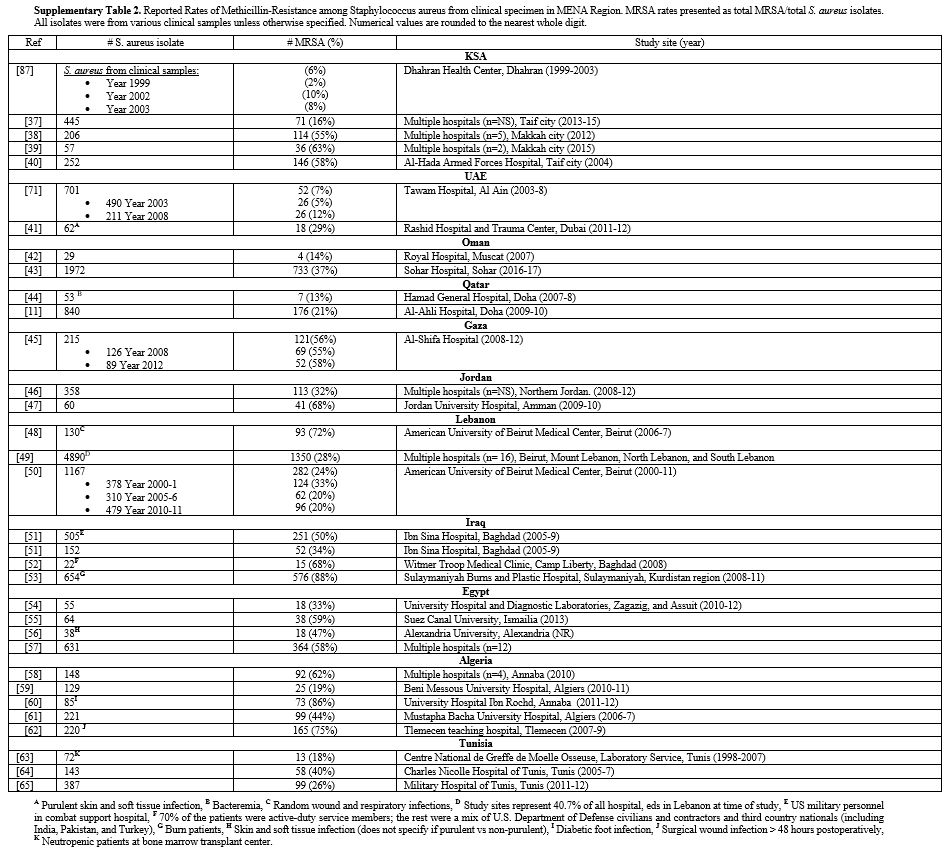

control efforts. MRSA Infections in the MENA Region: MRSA Infection Rates:

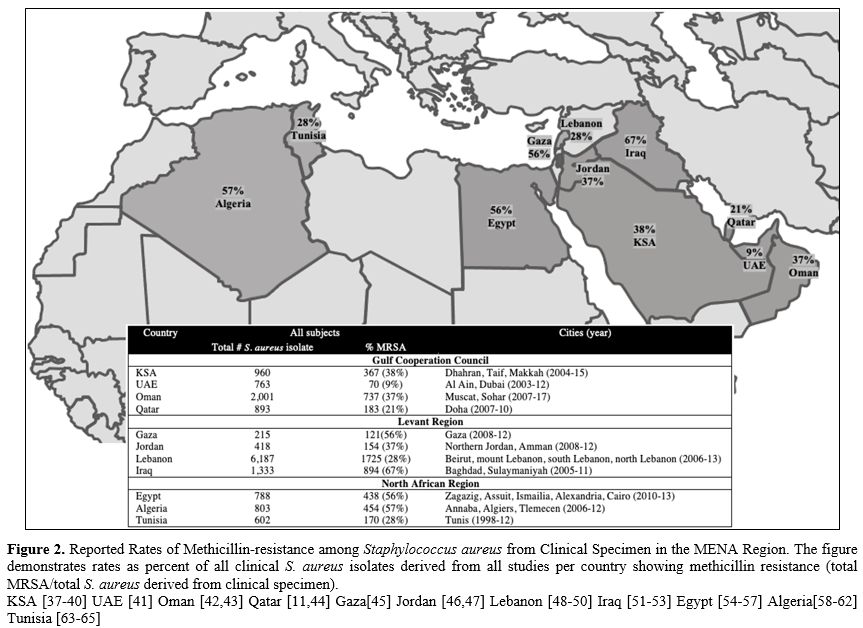

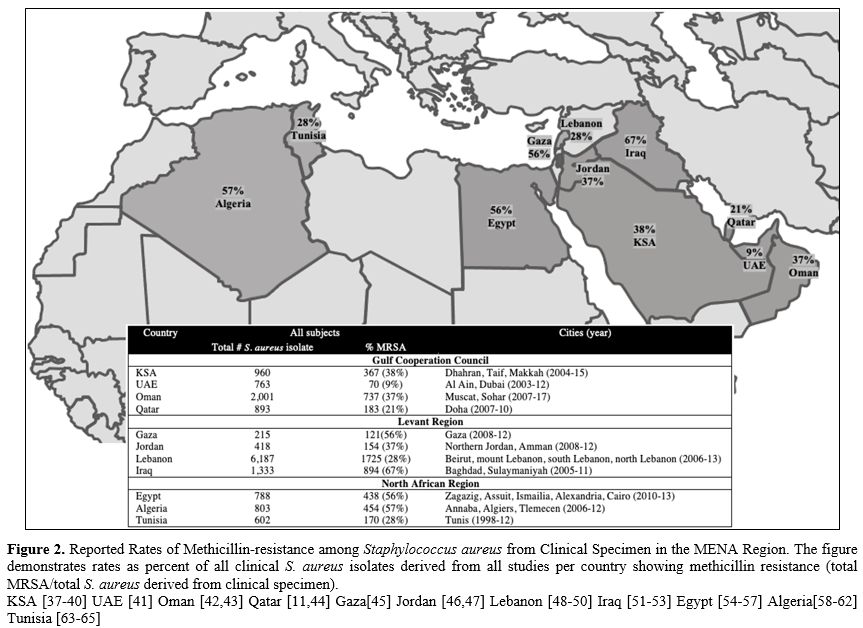

We report rates of MRSA infection as percent of clinical S. aureus

isolates showing methicillin resistance (total MRSA/total S. aureus

derived from clinical specimen). Figure 2 demonstrates percent methicillin resistance in total isolates derived from all studies per country. Supplementary table 2 provides more details for each cited study.

|

Figure 2.

Reported Rates of Methicillin-resistance among Staphylococcus aureus

from Clinical Specimen in the MENA Region. The figure demonstrates

rates as percent of all clinical S. aureus isolates derived from all

studies per country showing methicillin resistance (total MRSA/total S.

aureus derived from clinical specimen). KSA [ 37-40] UAE [ 41] Oman [ 42,43] Qatar [ 11, 44] Gaza[ 45] Jordan [ 46,47] Lebanon [ 48-50] Iraq [ 51-53] Egypt [ 54-57] Algeria[ 58-62] Tunisia [ 63-65]

|

When examining all isolates recovered per country, methicillin-resistance ranged from 9%-38% in GCC,[11,37-44] 28%-67% in the Levant,[45-53] and 28%-57% in North African states.[54-65]

In the GCC, lower rates were recorded in UAE and Qatar compared to Oman

and KSA. In UAE, the highest rate reached 29% in a study from Dubai

examining 62 S. aureus isolates derived from purulent skin and soft

tissue infections (SSTI).[41] In the Levant and North

Africa, Lebanon and Tunisia again had the lowest rates in clinical

isolates. Notably, one of the studies from Lebanon saw a rate of 72%

resistance in 32 isolates.[48] These isolates were

randomly selected, not consecutive, and examined only wound and

respiratory specimen. A subsequent

study testing 4,890 isolates from 16 different hospitals across Lebanon

showed a much lower rate of 28%.[49] In Iraq, very high rates were seen in combat support hospitals among U.S. military personnel,[51,52] particularly when examining skin and soft tissue infections (SSTI), and in a burn center where the rate reached 88%.[53] In North Africa, Algeria reached a high of 86% in Annaba when examining diabetic foot infections.[60] A high rate of 75% in another study was also seen in surgical wound infections >48 hours postoperatively in Tle mecen.[62]

On the other hand, a study from Algiers showed a lower rate of 19%

which again highlights the varying epidemiology depending on site

within a country.[59] When testing clinical isolates

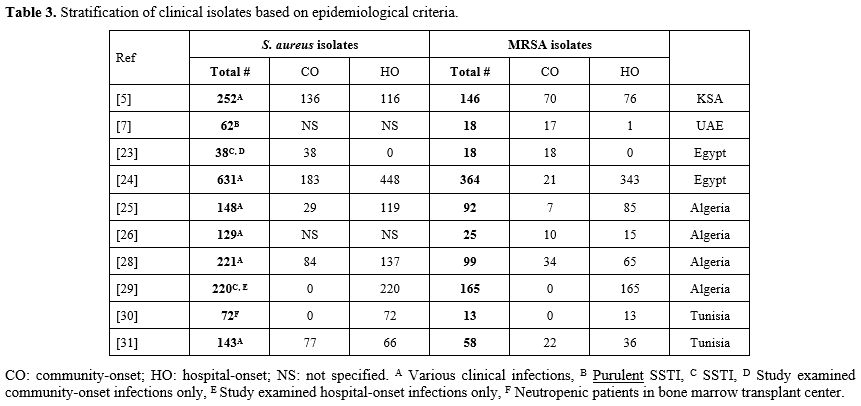

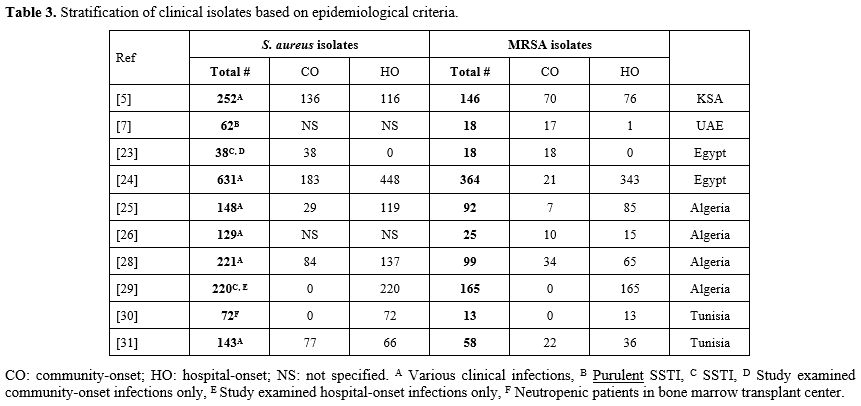

from neutropenic patients in Tunisia, a rate of 18% was detected, still lower than most studies in Egypt and Algeria.[63] Only few studies specified site of acquisition based on epidemiological criteria, i.e., CO-MRSA vs HO-MRSA, outlined in table 3. Based on these few studies, isolates causing hospital-onset infections showed higher rates of methicillin resistance. S. aureus isolates causing

community-onset infections had 51% methicillin resistance in KSA,[40] 12%-47% in Egypt,[56,57] 24%-40% in Algeria,[58,59,61,62] 29% in Tunisia.[64] In Egypt, the 40% rate was in community-onset SSTI.[56] On the other hand, isolates causing hospital-onset infection had 66% resistance in KSA,[40] 77% in Egypt,[56,57] 47%-75% in Algeria,[58,59,61,62] 18%-55% in Tunisia.[63,64]

|

Table 3. Stratification of clinical isolates based on epidemiological criteria.

|

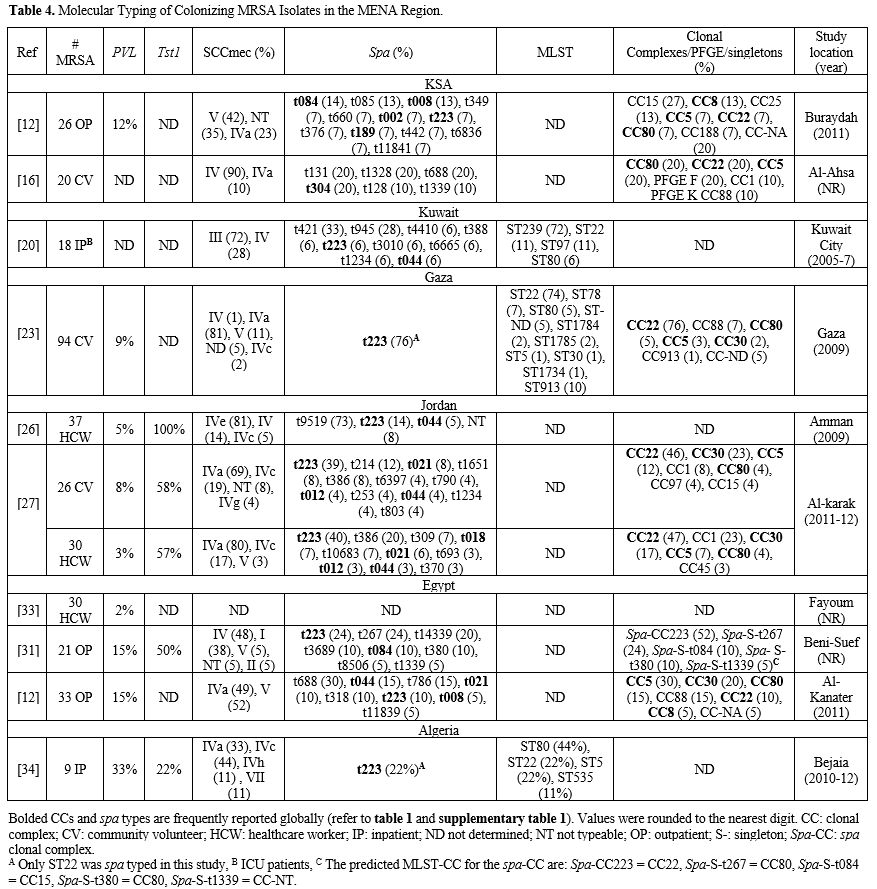

Molecular Types of MRSA in MENA Region:

As expected, heterogeneity between studies in the typing techniques

utilized and the reporting of results was evident. Some studies

reported SCCmec types alone while others reported MLST and/or spa

typing with or without CC assignment. Therefore, determining the

relatedness of reported strains from different studies is challenging.

For example, in the study from Bahrain, PFGE typing was used. While

this is a good tool to investigate relatedness of strains in an

institution, it does not allow for comparison with other centers.[6]

Studies

demonstrated a wide clonal diversity across the region. This was

evident by the large number of different spa and/or MLST types and

their corresponding CCs. Furthermore, the epidemiology varied

depending on center, city, study period, and subject cohort. The

bulk of studies recovered in our review did not classify their samples

based on site of acquisition (CO-MRSA vs HO-MRSA). This would have been

a valuable tool to distinguish the epidemiology between community and

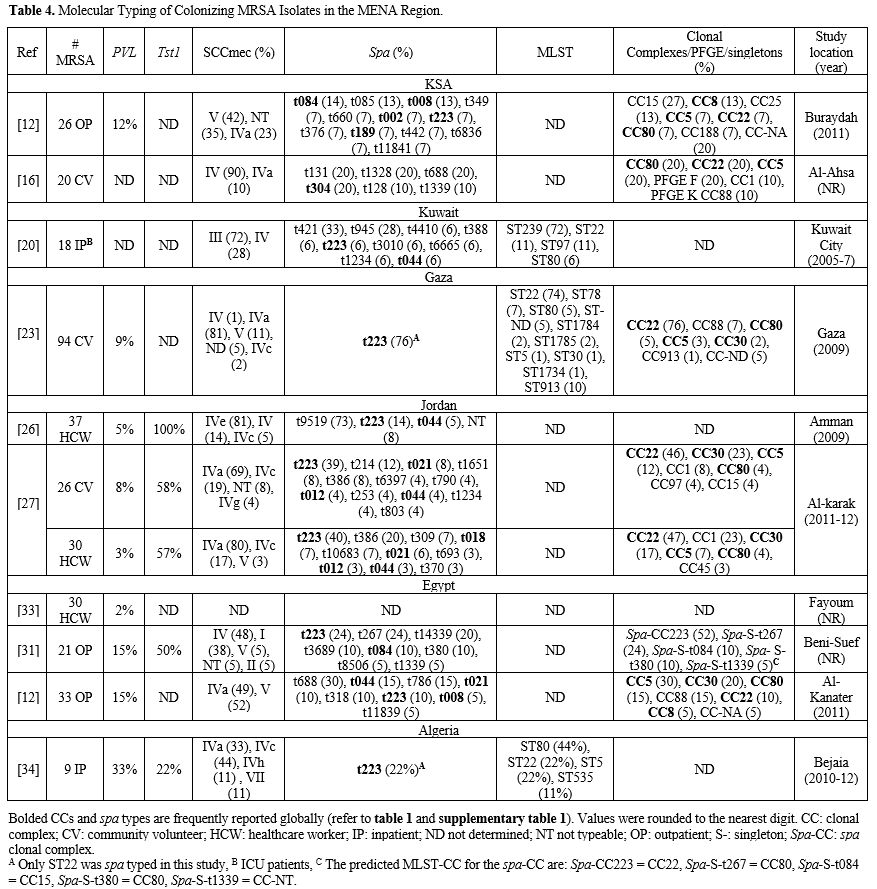

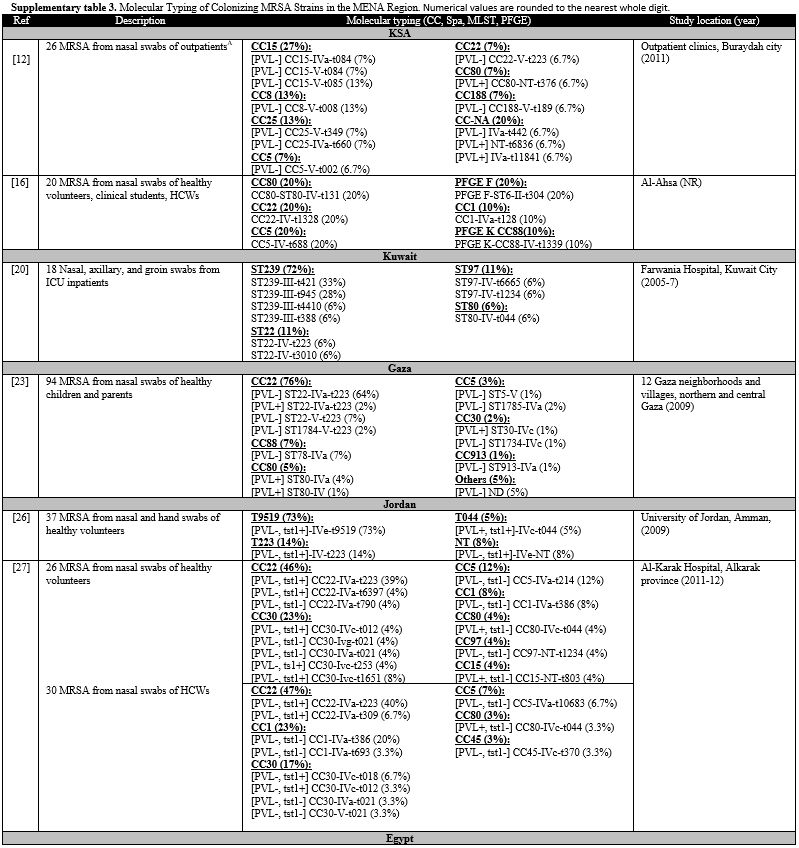

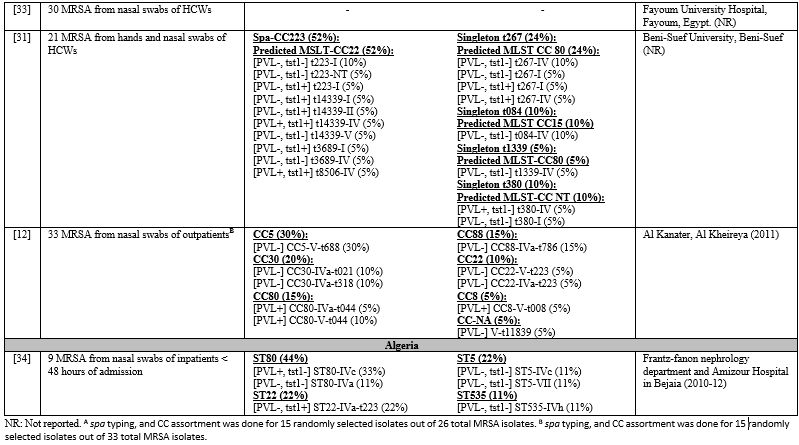

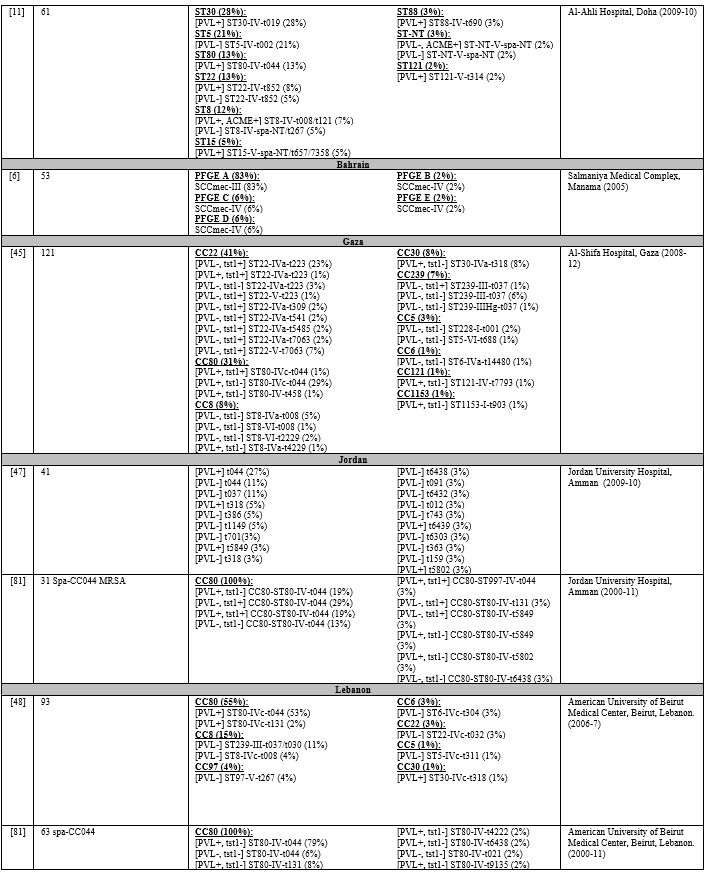

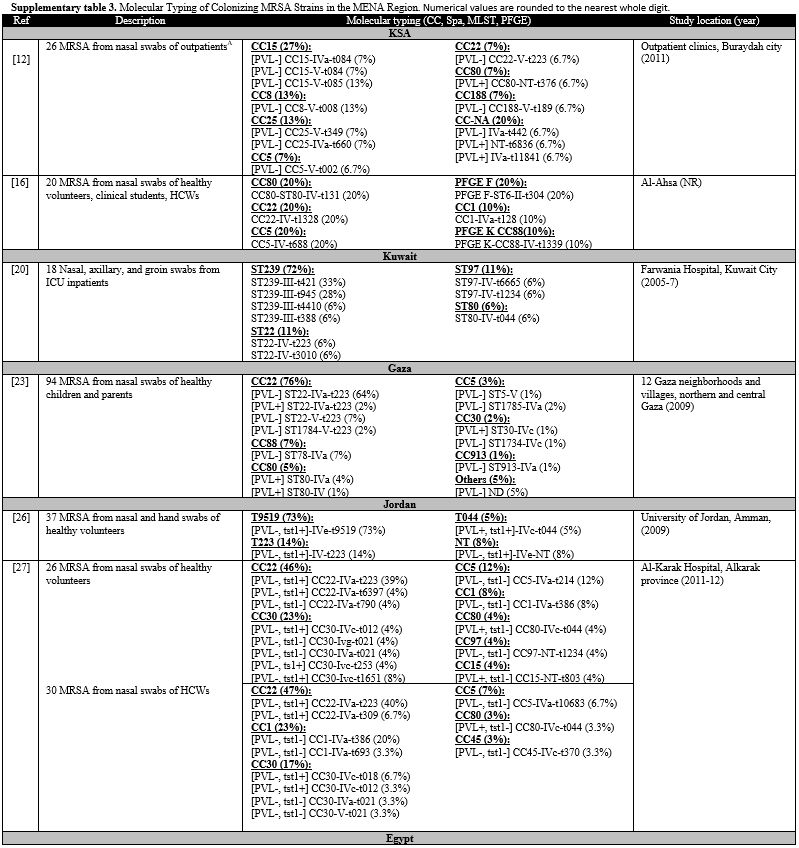

healthcare settings. All studies examining colonizing MRSA were limited by a small sample size. Table 4 lists the relative frequencies of PVL, Tst1, SCCmes, MLST, spa, and CCs in colonizing strains. Supplementary table 3 organizes the genotypes into clones. In the GCC, PVL gene carriage reached 12% in outpatients in KSA.[12] Tst1 gene prevalence was not examined in studies from GCC.[12,16,20] Low PVL carriage was also detected in the Levant, 3%-9%.[23,26,27] Tst1 was examined in Jordan only, and very high rates were depicted in both community and healthcare settings.[26,27] In North Africa, PVL carriage was low in Egypt, 2%-15%,[12,31,33] but reached 33% in Algeria,[34] while Tst1 carriage reached 22% in Algeria,[34] but 50% in Egypt.[31]

|

Table 4. Molecular Typing of Colonizing MRSA Isolates in the MENA Region.

|

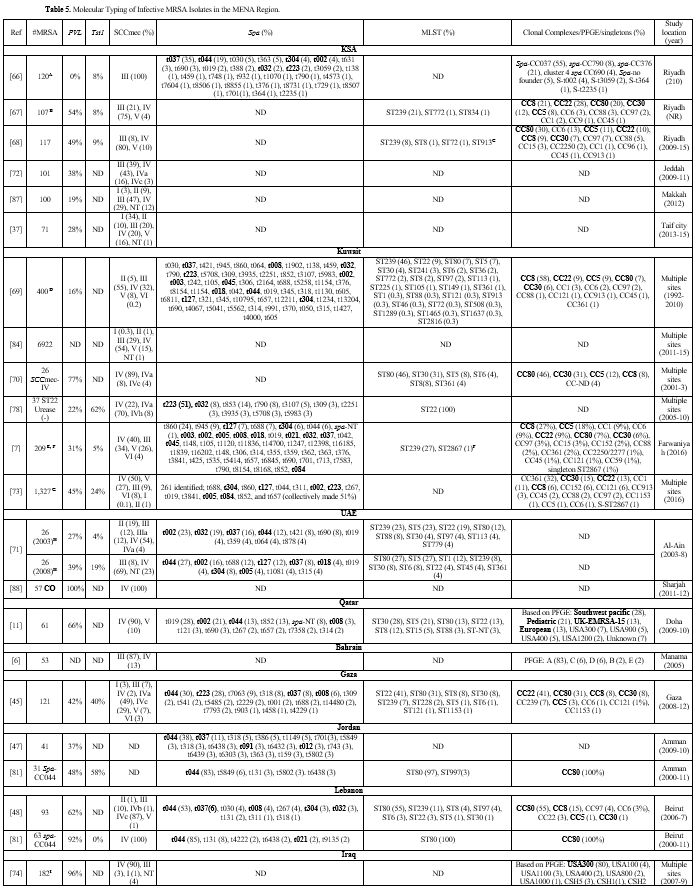

Table 5

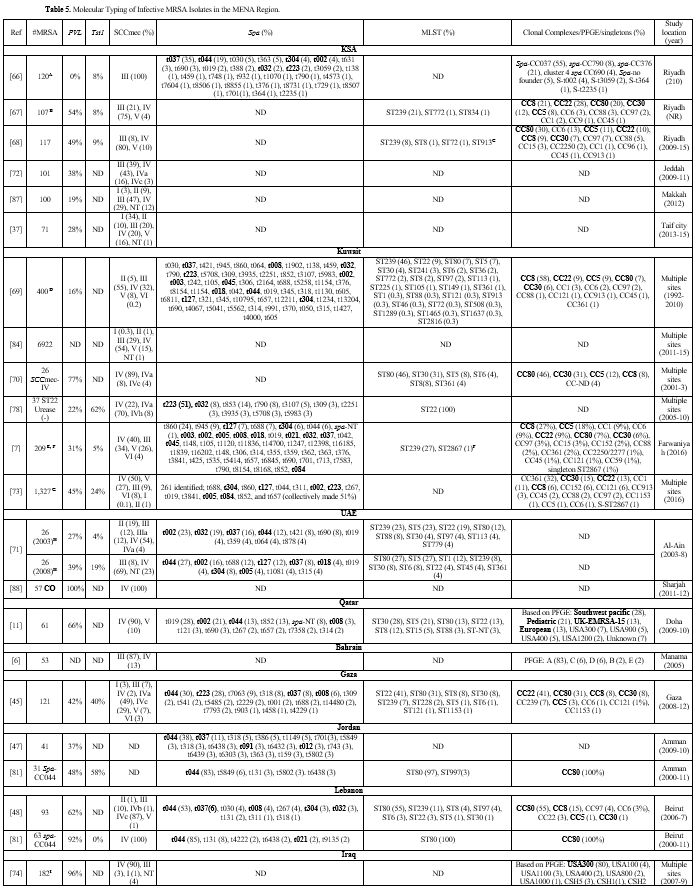

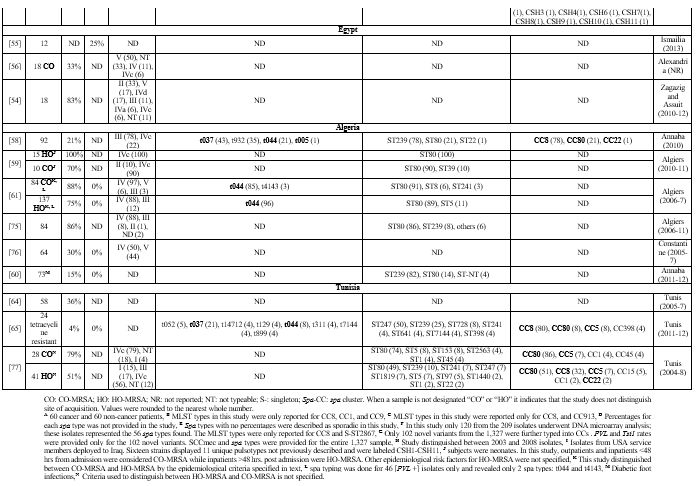

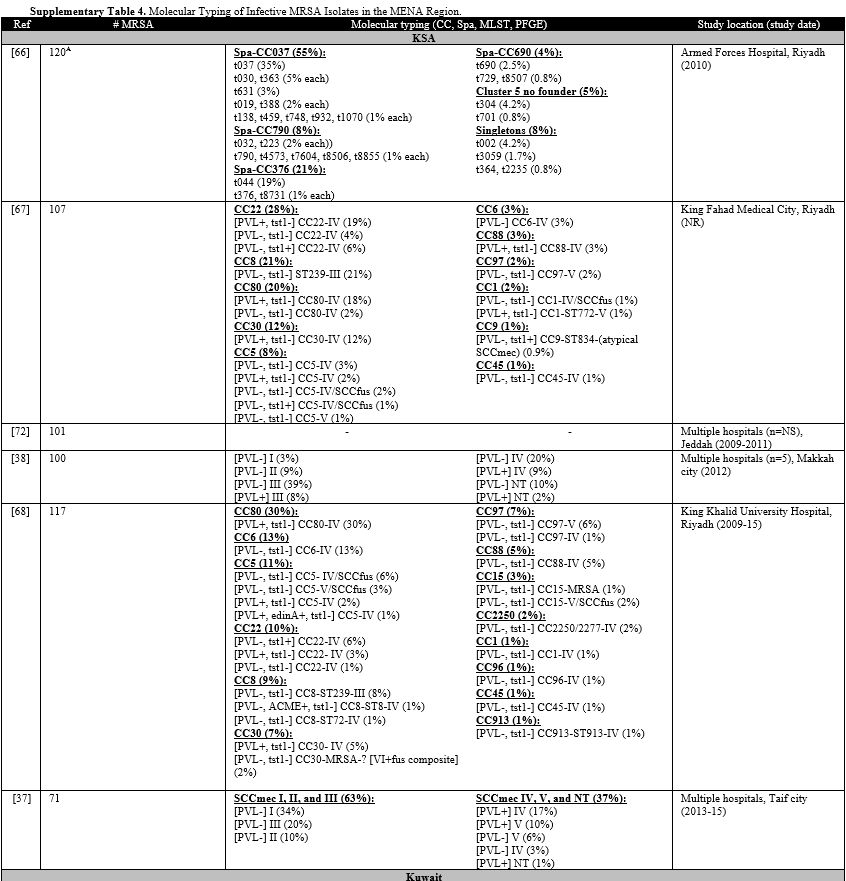

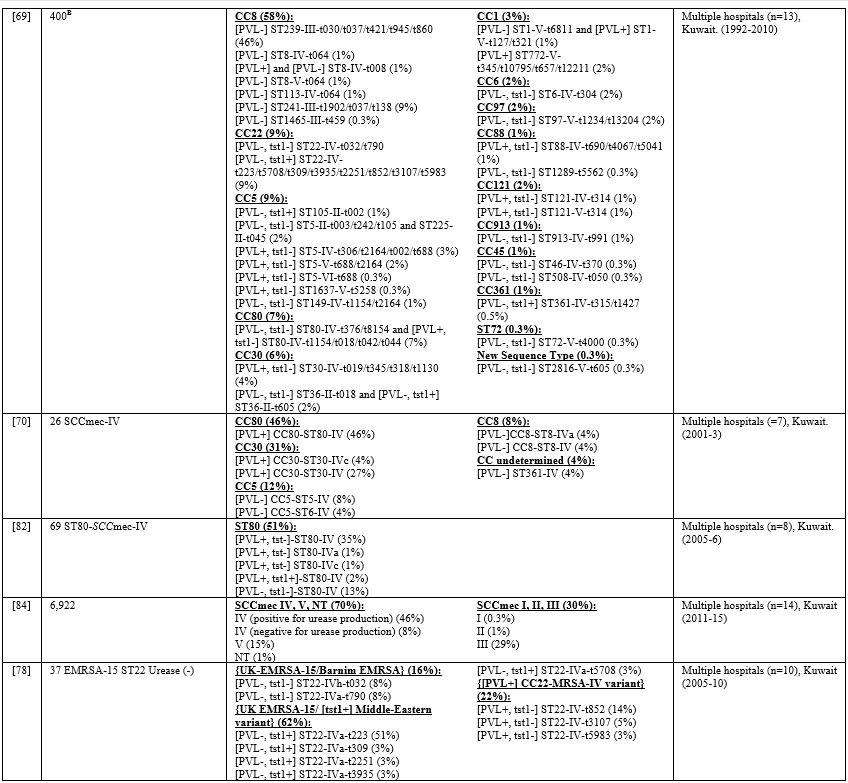

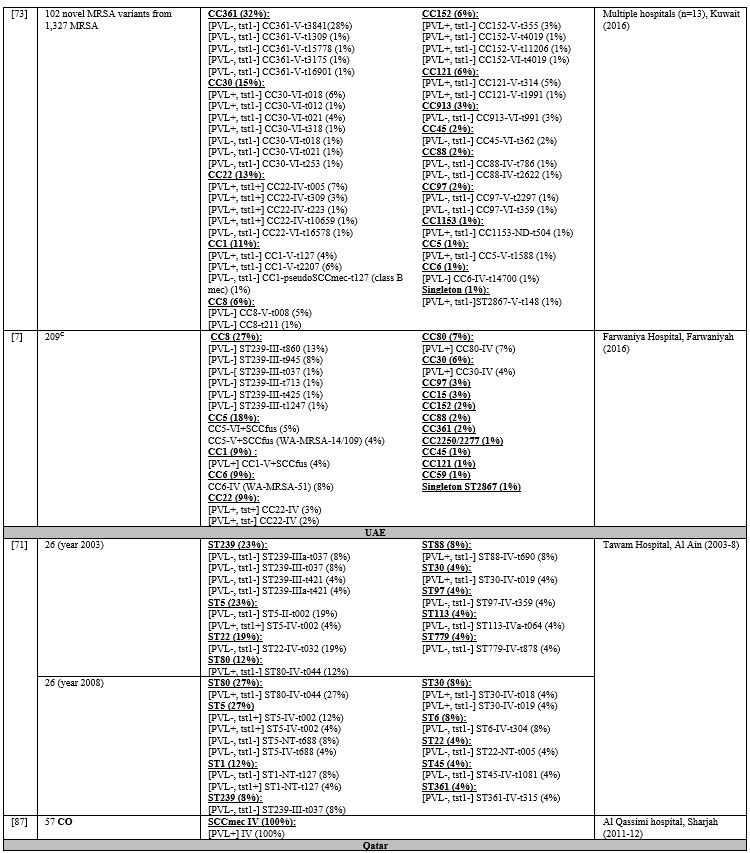

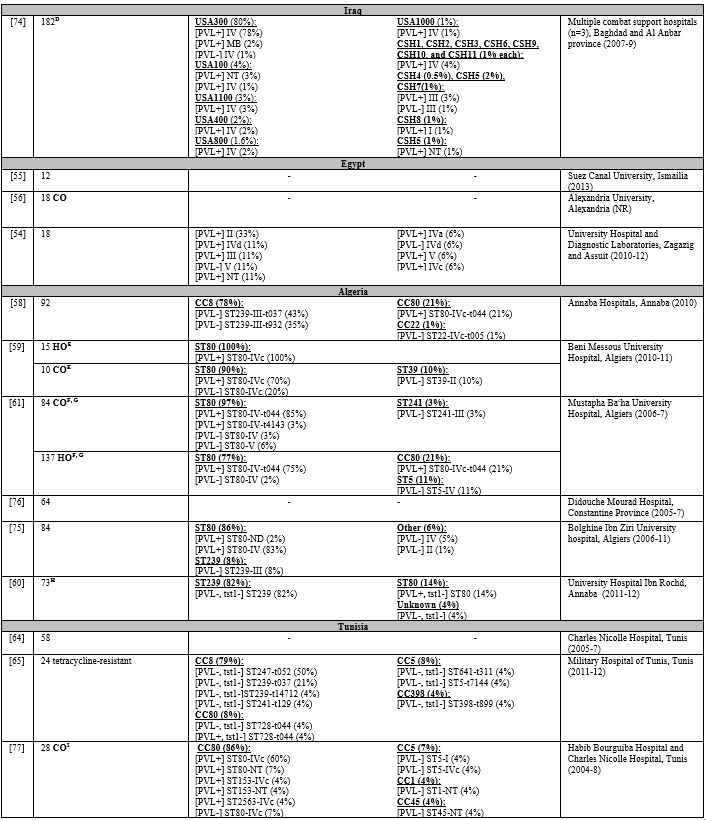

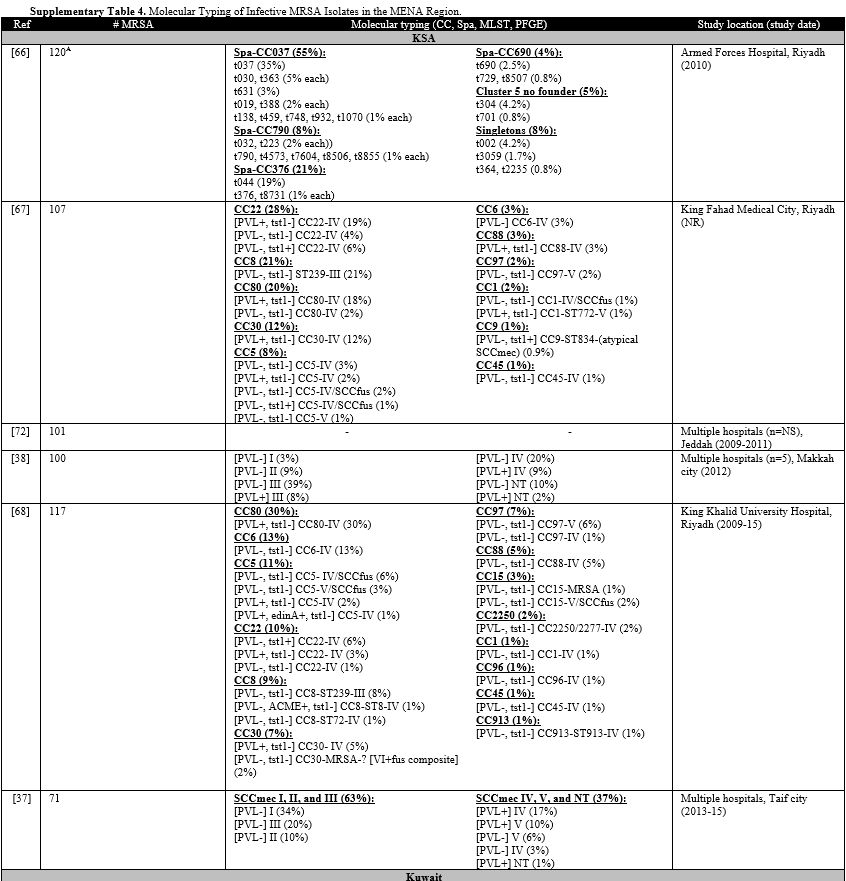

lists the PVL, Tst1, SCCmes, MLST, spa, and CCs in infective strains.

Supplementary table 4 organizes the genotypes into clones. In GCC, PVL

carriage ranged from 0%-77%,[7,11,37,66-73] while Tst1 carriage ranged from 4%-24%.[7,66-68,71,73] In the Levant, PVL gene was detected in 37%-96% of infective MRSA.[45,47,48,74] Tst1 gene was screened for in Gaza and detected in 40% of isolates.[45] PVL detection rate ranged from 21%-88%.[54,58,75,76] Most cited studies did not determine Tst1 carriage except one from Algeria where none of the isolates carried the toxin gene.[61]

|

Table 5. Molecular Typing of Infective MRSA Isolates in the MENA Region. |

Both

HA-MRSA and CA-MRSA genotypes were frequently detected among colonizing

and infective strains in the MENA region. Most of the globally

prevalent spa types were detected in the Arab countries, as illustrated

in supplementary table 1. Spa

types belonging to European CA-MRSA, Brazilian/Hungarian HA-MRSA, and

EMRSA-15 HA-MRSA were most widely distributed across the region. The

most frequently detected CCs were CC5, CC8, CC22, CC30, and CC80,

which are globally spread complexes briefly reviewed in table 1. In this section we review the epidemiology of these CCs in the MENA Arab world. Clonal Complex 5: Members of CC5 are widespread geographically.[8]

Established clones from this group can carry SCCmec-I, II, III, IV, and

V and can be HA-MRSA and CA-MRSA. It consists of several clones including

the South German Epidemic HA-MRSA (ST228-SCCmec-I), Geraldine CA-MRSA

(ST5-SCCmec-I), West Australian (W.A.) MRSA-18, and -21 (both

ST5-SCCmec-I) and -48 (ST835-SCCmec-I), New York/Japan (ST5-SCCmec-II),

and Paediatric (ST5-SCCmec-IV) clones, among others.[8]

The last 2 clones are described as pandemic. Another clone previously

described is ST5-SCCmec-V which is colloquially known as WA MRSA-11,

-14, -34, and -35. This isolate was detected in Australia, Ireland, and

Germany.[8] Colonizing isolates of this group were detected in KSA,[12] Gaza,[23] Jordan,[27] and Egypt.[12]

These included the CC5-V and CC5-IV which are likely related to WA MRSA

and Paediatric clones, respectively. All these strains were [PVL-]. In

Egypt, CC5-V made up 30% of colonizing strains from outpatients.[12] In

infective strains from the MENA, the CC5 and its clones were among the

less commonly detected strains. Detected SCCmec types were II, IV, and

V. Therefore, observed clones included the Paediatric, New York/Japan,

and WA MRSA-(11, -14, -34, and-35). Clonal Complex 8: Several clones belong to this complex, including both CA-MRSA and HA-MRSA.[8]

Its strains can carry SCCmec-I, IV, V, and VIII. MLST types include

ST8, ST72, and ST239/ST240/ST241. It houses the first known MRSA clone

(ST250-SCCmec-I), known as Ancestral MRSA. This clone is disappearing

with time. It also houses the famous Iberian (ST8-SCCmec-I), USA300

CA-MRSA ([PVL+] ST8-SCCmec-IV+ACME) and Brazilian/Hungarian HA-MRSA

([PVL-] ST239-SCCmec-III). USA300 has disseminated throughout the

United States of America (U.S.) in few years. Sporadic cases have been

identified in some European countries. The Brazilian/Hungarian HA-MRSA

is considered the oldest pandemic strain. It is described from

countries in every continent. This clone is always [PVL-]. It is

prevalent in Europe, Australia, Middle East, and Asia and can be

divided into 3 clades [European, Asian, and south American]. ST240 and

241 are closely related to ST239, each differ in mutations within 1

housekeeping gene only.[8]In MENA region, the Brazilian/Hungarian HA-MRSA was very prevalent in some centers in Kuwait[7,69] and KSA[66,67] but had a decreasing presence in a center from UAE,[71] and was completely absent in 1 hospital in Qatar.[11] It had a modest presence in the Levant.[45,47,48,74] It was notably nonexistent in combat support hospitals in Iraq.[74] In Algeria, It was very common in Annaba but not in Algiers,[58-61,75] and in Tunisia, it was frequently encountered in HO-MRSA isolates but not CO-MRSA.[75] All ST239 isolates in the MENA region were [PVL-] and had SCCmec-III. Spa types t037, t030, and t008 were most commonly seen.[12,16,20,23,26,27,31,34]The

USA300 CA-MRSA was overall less commonly encountered than the

Brazilian/Hungarian clone. It was isolated infrequently in KSA,[67,68] Kuwait,[69,70] Qatar,[11] Gaza,[45] and Lebanon.[48]

In Kuwait, it accounted for 8% of 26 SCCmec-IV MRSA isolates only, as

opposed to the European CA-MRSA, which made up 46%. Nonetheless, USA300

was very common in Iraq, where it accounted for 80% of infective

isolates from deployed U.S. soldiers.[74] The

clinical specimen was 95% from wound infections. Most non-wound

isolates were not USA300. Almost all USA300 isolates were [PVL+].

Despite being in separate geographical locations, similar pulsotypes

were identified in the 3 combat support hospitals (CSH), which

indicated the same origin of MRSA.[74] It is possible that soldiers were colonized before deployment as USA300 is a prevailing clone in the U.S.[8] Finally, a [PVL-] CC8-V-t008 clone was detected in few isolates from KSA,[12] Egypt,[12] and Kuwait.[73] This clone was previously described in Saxony and Australia.[8]Clonal complex 22: This complex contains multiple MRSA lineages.[8]

The best example is the ST22-SCCmec-IV pandemic clone, also known as

UK-EMRSA-15 HA-MRSA. When present, it tends to become abundant. It is

considered HA-MRSA but can also disseminate in the community. In

previous reports, it accounted for 50%-80% of isolates from countries

in Europe. It is typically [PVL-] and [Tst1-], but variants carrying

either or both toxins exist. For example, [PVL+] ST22-SCCmec-IV was

previously described in a large hospital outbreak in Germany.[8] This variant was also detected in other parts of Europe. A [PVL+, Tst1+] variant was previously identified in India.[8]

Investigators hypothesize that these variants could have a polyphyletic

origin since they can exist in epidemiologically unrelated settings. A

[PVL-] SCCmec-V clone was also infrequently detected in Saxony and

western Australia. CC22-SCCmec-I, II, or III are not described in the

literature.[8] [PVL-] ST22-SCCmec-IV or its related spa types were commonly reported in colonizing strains from the MENA region,[12,16,20,23,27,31,34] particularly common in Gaza, Jordan, Egypt, and Algeria.[12,23,27,31,34] This clone was also prevalent in infective strains from the GCC and Gaza. It was reported in 10%-28% of isolates from KSA,[67,68] 13% in Qatar,[11] and 9% in Kuwait.[7,69,73]

In UAE, it accounted for 19% of isolates in 1 center in 2003 but then

dropped to 4% in 2008, showing a decreasing presence with time while

other clones dominated.[71] The ST22-SCCmec-IV clone

was exceptionally common in Gaza, where it made up 41% of isolates in 1

study. On the other hand, this clone was infrequently encountered in

the other Levant and North African countries.[47,48,58-61,65,74,75,77] All

the CC22 isolates from the MENA carried either SCCmec-IV or V. The most

common spa types were t223 and t032. The majority were [PVL-] as

expected. Nonetheless, the [PVL+] variant was detected in KSA, Kuwait,

and Qatar, where, in some centers, this variant exceeded the [PVL-]

ST22 strains.[11,68,69]

Furthermore, many isolates from KSA and Kuwait were [Tst1+], also known

as the "Middle Eastern" variant. In Kuwait, 62% of a subset of urease

(-) EMRSA-15 isolates belonged to the Middle Eastern variant.[78]

This variant mostly carried SCCmec-IVa and was [PVL-], except for some

isolates from Kuwait, [PVL+] indicating the potential to acquire both

toxins. Notably, the bulk (91%) of infective isolates in Gaza were

[Tst1+].[45] Nonetheless, these were collectively referred to as the "Gaza" strain.[45] The Gaza strain also exists in Jordan where it was dominant in colonizing strains in 1 study.[27] On the other hand, it was not detected in studies from Lebanon.[48,79]

The Gaza strain was associated with the SCCmec-IVa-t223 genotype. Like

the Middle Eastern variant, the Gaza strain was mostly [PVL-].While

the PFGE analysis of the Gaza strain in Gaza showed 76% pattern

similarity with UK-EMRSA-15, some distinguishing features exist. The

UK-EMRSA-15 is associated with SCCmec-IVh-t032 and t022 instead of

SCCmec-IVa-t223.[23,27] Furthermore, Unlike UK-EMRSA-15, the Gaza strain is susceptible to ciprofloxacin and resistant to tetracycline.[23,27]

Some of the ST22-SCCmec-IV strains in GCC and North African Arab

regions also carried SCCmec-IVa-t223 distinguishing them from

UK-EMRSA-15 clone.[12,23,27,34,45,78] One study examined 47 CC22-SCCmec-IV isolates from patients from KSA, Abu Dhabi, Kuwait, and Germany.[80] Six distinct albeit related strains were detected. Only 9 isolates showed complete resemblance to the UK-EMRSA-15.[80]

The study concluded that none of the isolates from Riyadh were true

UK-EMRSA-15. True UK-EMRSA-15, however, was identified in Abu Dhabi and

Kuwait.[80] Lastly, [PVL-] CC22-SCCmec-V was detected in few strains from KSA and Gaza.[12,23,45] This clone carried t223 and t7063 spa types and was [Tst1+] in Gaza. Clonal complex 30: Important clones include UK-EMRSA-16 HA-MRSA (ST36/39-SCCmec-II) and Southwest Pacific CA-MRSA ([PVL+] ST30-SCCmec-IV).[8]

The former was an important clone in Europe but is becoming rare. The

latter is widespread globally. A [PVL-, Tst1+] ST30-SCCmec-IV is

sporadically isolated from Ireland and Australia.[8] Overall,

CC30 was only occasionally encountered in most of the countries in the

region. It was detected in few colonizing isolates from Gaza,[23] Jordan,[27] and Egypt.[12]

Most colonizing isolates were [PVL-], and in Jordan, several of them

were [Tst1+] It was also rarely seen in infective isolates from KSA,[68] Kuwait,[69] and UAE,[71] Gaza,[45] Lebanon,[48] and Jordan.[47] None of the studies from Algeria and Tunisia isolated CC30.[65,77] However, this was the most common clone in infective isolates from 1 center in Qatar.[11] Also, it made up 31% of a sample of 26 SCCmec-IV isolates in Kuwait.[70] Almost all isolates from the region carried SCCmec-IV, resembling Southwest pacific CA-MRSA..[27] Associated spa types were t019 and t018 in the GCC,[68,69,71] and t318 in the Levant.[45,47,48] Unlike colonizing strains, all infective isolates from this region were [PVL+] except for 1 in Jordan. The UK-EMRSA-16 HA-MRSA was also rarely reported in the region; only 8 isolates from Kuwait.[69] Finally, when isolates carrying novel genotypes in Kuwait were tested, 15% carried CC30-SCCmec-VI.[73] Clonal complex 80:

This complex houses the European CA-MRSA clone (ST80-SCCmec-IV), which

gains its name due to its significant presence throughout Europe.

However, this clone is encountered worldwide; most isolates belonging

to CC80 carry [PVL+] ST80-SCCmec-IV and IV variants. [PVL-] strains are

infrequently detected. ST80-SCCmec-IV or the associated spa types were detected in colonizing strains from all recovered studies.[12,16,20,23,27,31,34] Among infective strains, it was detected in 20-30% of isolates from KSA,[67,68] 7% in Kuwait,[7,69] and 13% in Qatar.[11] In UAE, one center experienced a rise in rates from 12% in 2003 to 27% in 2008.[71] When examining a sample of SCCmec-IV isolates in Kuwait, 46% were ST80-SCCmec-IV.[70]

This clone was even more prevalent in infective isolates from the

Levant and North Africa. It made up 31% of isolates in Gaza,[45] and 55% in Lebanon.[48] In Jordan, [PVL+] t044 and [PVL-] t044 were detected in 27% and 11% of isolates, respectively.[47] This clone was completely absent in an Iraqi study examining clinical isolates from U.S. soldiers.[74] In Algeria, this was the most frequently encountered clone in Algiers, 77%-100% of isolates.[59,61,75]

This was true even for HO-MRSA isolates, indicating the infiltration of

this CA-MRSA clone into the hospital setting. However, its presence was

less frequently encountered in studies from a different city, Annaba.[58,60] In Tunisia, it accounted for 51% of HO-MRSA and 86% of CO-MRSA.[77]There

is evidence that isolates belonging to European CA-MRSA in the region

could have different evolutionary lineages. For example, PFGE typing

revealed 21 different clonal groups among spa-clonal-cluster-044

isolates from Lebanon and Jordan.[81] Moreover, the

PVL gene was detected more frequently in the Lebanese subset, while the Tst1 gene was detected only in the Jordanian subset.[81]The [PVL-] variant was infrequently encountered in KSA,[67] Kuwait,[69,82] Jordan,[47,81] Lebanon,[81] Algeria,[59,61] and Tunisia.[65,77] A [Tst1+] variant was detected in Kuwait,[82] Gaza,[45] and Jordan.[81] On the other hand, all strains in UAE,[71] Qatar,[11] Gaza[45] were [PVL+]. The most encountered spa type was t044.[45,48,58,61,65,81]Other Clonal Complexes: CC15 was detected in a small number of colonizing isolates from KSA,[12] Jordan,[27] and Egypt.[31] These were carrying t083, t084, and t085. It was also seen in some infective strains from KSA,[68] Kuwait,[7] and Tunisia.[77] This CC is rarely described.[8] It was detected in a collection of strains from Italy in 1980, 4 SCCmec-I isolates.[8] More recently, it was reported in Europe, Iran, Gabon, and the Gulf of Guinea.[12]

In Europe, it accounted for 17% of MRSA and methicillin-susceptible

(MSSA) isolates combined and carried ST1, ST15, ST188, ST772, and

ST1835. In KSA, isolates of CC15 carried both SCCmec-IVa and V.[12] In Jordan, a novel genotype, [PVL-,Tst1+]-IVe-t9519, made up the bulk of colonizing isolates from Amman.[26]There

are still other CCs and clones identified in the region but seem to be

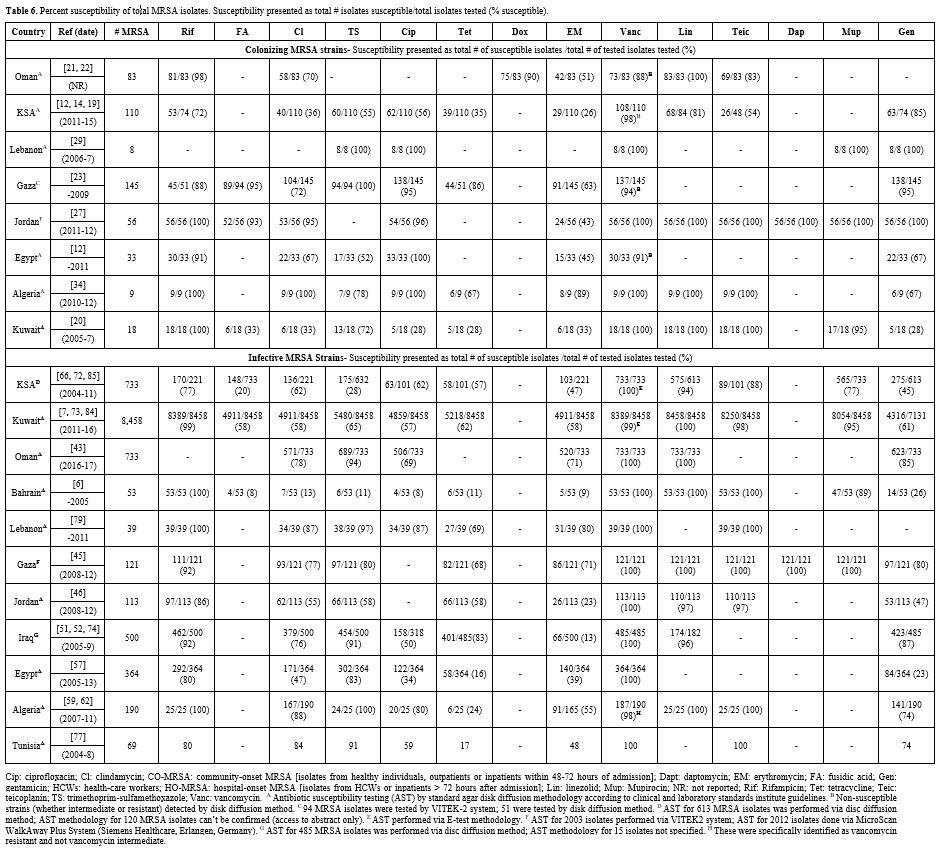

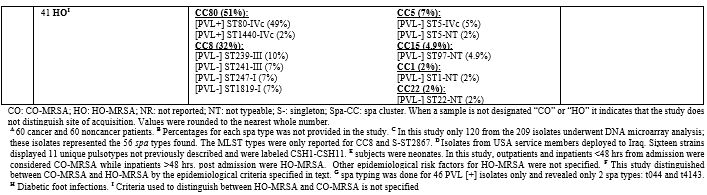

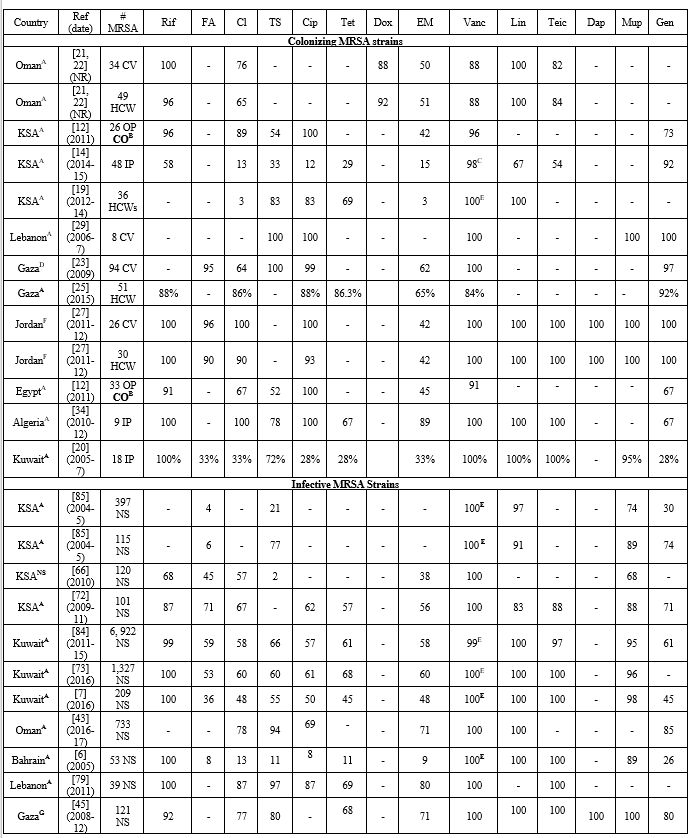

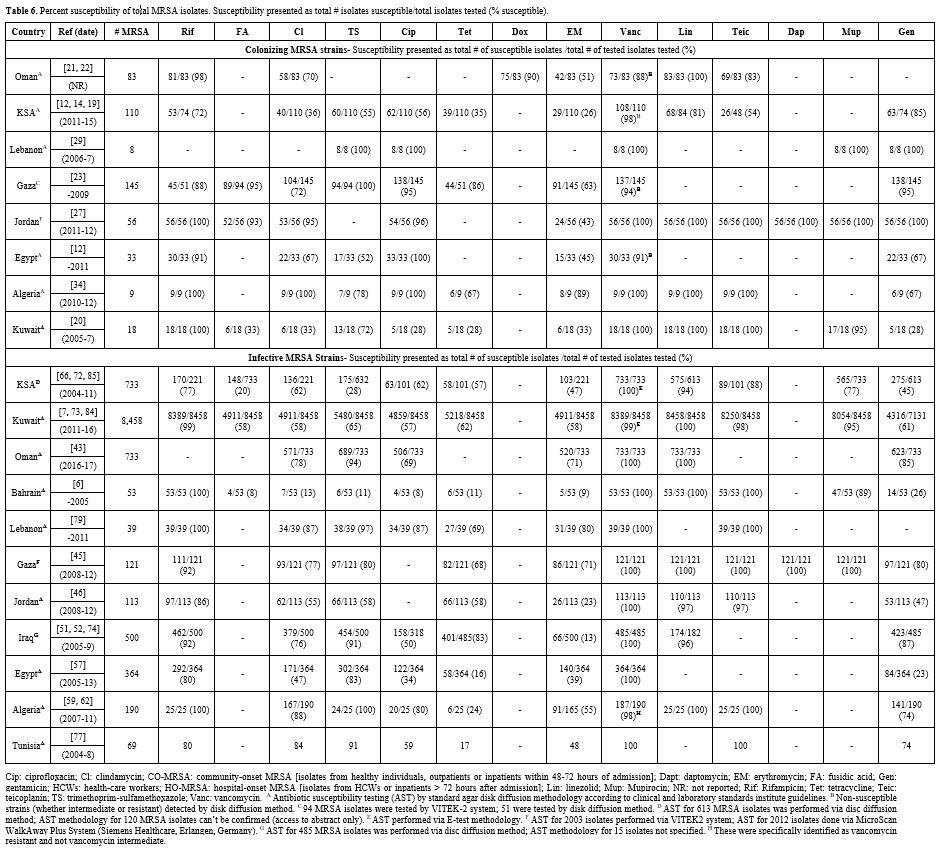

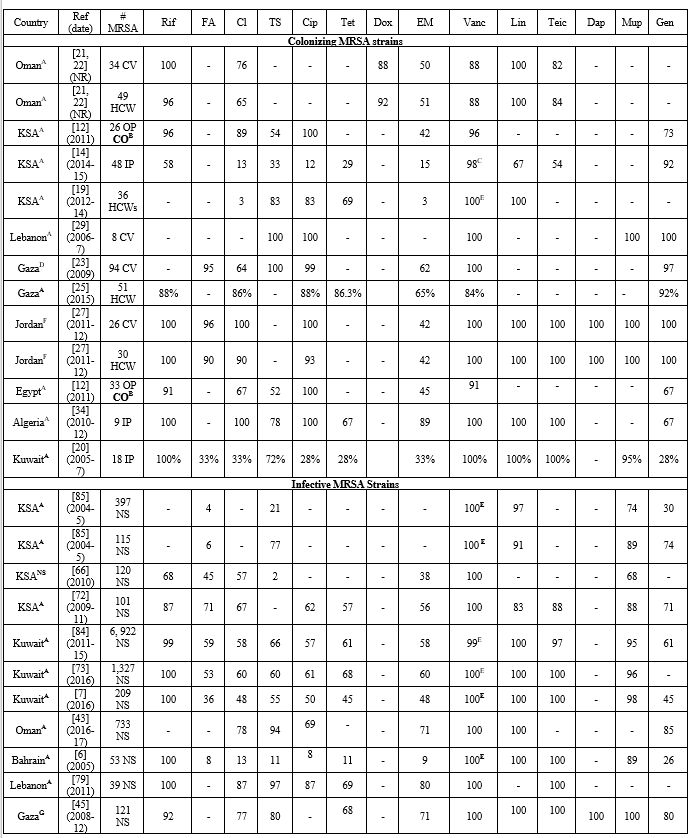

of lower prevalence compared to the 5 main CCs we chose to discuss. Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns of MRSA in the MENA Region:

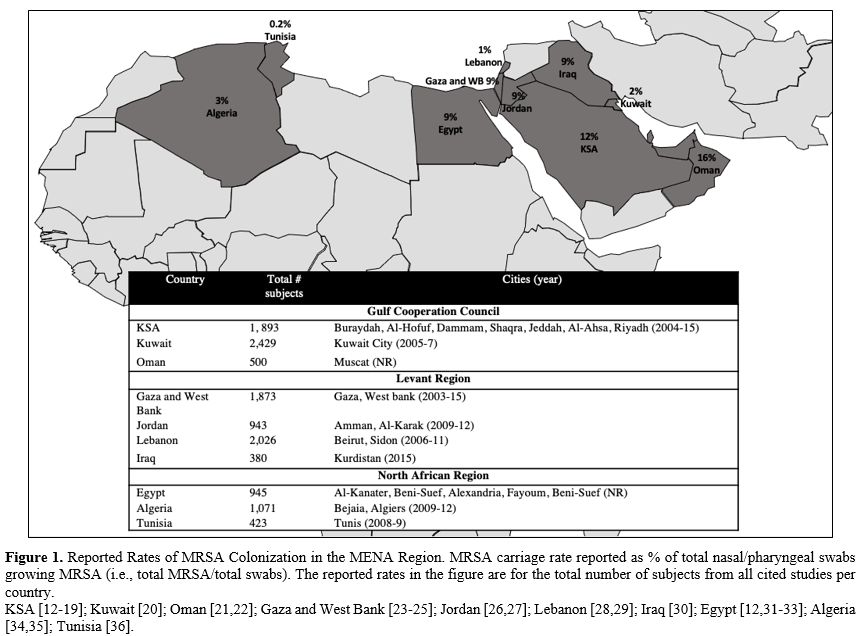

An in-depth description of the antimicrobial susceptibility of MRSA in

the MENA region is not the primary objective of our review. Therefore,

we do not discuss this topic in detail. Table 6 lists cumulative susceptibilities for 462 colonizing and 11, 373 infective MRSA isolates per country. Supplementary Table 5

provides the susceptibilities from individual studies. The

susceptibility ranges are wide for some antimicrobials, indicating a

significant difference in resistance patterns between different centers

within a country.

|

Table 6. Percent

susceptibility of total MRSA isolates. Susceptibility presented as

total # isolates susceptible/total isolates tested (%

susceptible).

|

Antimicrobial Resistant patterns of Colonizing MRSA: Studies from GCC and North African Arab countries showed high resistance to TMP-SMX.[12,14,19,20,34,83] On the other hand, all isolates from the Levant were susceptible to this agent.[23,29] For ciprofloxacin, isolates from North Africa and Levant were largely sensitive as opposed to the GCC.[12,14,19,20,23,27,29,34]

Nonetheless, studies from Gaza and Jordan showed that high resistance

to ciprofloxacin could be encountered in isolates retrieved from

healthcare workers.[25,27] Furthermore, while some centers in KSA showed high resistance, others showed 100% susceptibility to ciprofloxacin.[12,14] Almost all countries showed high resistance to tetracycline, clindamycin, and erythromycin.[12,14,19-23,25,27,29,34]

Isolates also remained highly susceptible to rifampin in most centers.

Surprisingly, significant vancomycin resistance was detected in KSA,

Oman, Egypt, and Gaza.[12,14,21,22,25] The majority of these studies used Kirby Bauer's disk diffusion method using Mueller-Hinton agar[12,14,22,25] except for 1 study, which used E-test for minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC).[21] The remaining studies showed 100% susceptibility to vancomycin.[19,20,23,27,29,34] Isolates were almost universally susceptible to linezolid except in 1 study from KSA.[14] Antimicrobial Resistant patterns of Infective MRSA:

Infective MRSA in the MENA region were highly resistant against most

antimicrobials. Susceptibility to TMP-SMX varied widely depending on

the center. It reached acceptable to high levels in UAE and Oman in

some studies.[41,43,71] Strains from Lebanon and Iraq were highly sensitive to TMP-SMX as opposed to Gaza and Jordan.[45,46,79] Nonetheless, the Gaza strain commonly encountered in Gaza was susceptible to TMP-SMX.[23,27] Reported sensitivities to vancomycin, linezolid, and teicoplanin remained high among infective isolates in the region.[6,25,41,43,45,46,57,59,66,71,77,79,84,85] Exceptionally, 5% resistance to vancomycin was detected in 1 study from Egypt using the broth microdilution method.[54]ST22-IV clones from GCC were highly susceptible to rifampin, vancomycin, linezolid, and teicoplanin.[71,78] The UK-EMRSA-15 and its [PVL+] and [PVL-] variants all had high susceptibility to tetracycline but low to ciprofloxacin.[78] In contrast, [Tst1+] Middle Eastern variant was 100% sensitive to ciprofloxacin but only 70% to tetracycline.[71,78] The "Gaza strain" was susceptible to most tested antimicrobials, including ciprofloxacin and TMP-SMX.[23,27]

It was often resistant to tetracycline. When compared to ST22-IV

isolates from GCC, similar susceptibility rates were seen with few

exceptions. The Middle Eastern variant was similarly sensitive to

ciprofloxacin but, unlike the Gaza strain, was resistant to TMP-SMX.[78]

On the other hand, the [PVL+] and [PVL-] variants in GCC were similarly

sensitive to TMP-SMX but differed due to high resistance to

ciprofloxacin and high sensitivity to tetracycline.[71,78] ST239 isolates from UAE were sensitive to vancomycin, linezolid, teicoplanin but resistant to other tested agents.[71] In Egypt, they were highly resistant to tested antibiotics such as TMP-SMX, tetracycline, and gentamicin.[58]ST80-IV

CA-MRSA strains in GCC had high susceptibility rates to rifampin,

TMP-SMX, vancomycin, linezolid, teicoplanin, and gentamicin.[25,71,82] Furthermore, the majority of spa-clonal cluster-044 isolates from the Levant were susceptible to rifampin and gentamicin,[81] which was consistent with GCC reports.[71,82]

The Lebanese isolates were often resistant to tetracycline, while the

Jordanian isolates showed significantly higher resistance to

erythromycin.[81] In Egypt, this strain was often susceptible to TMP-SMX but resistant to tetracycline.[58]

Discussion

This

review highlights a significant threat imposed by MRSA on both the

community and healthcare settings within the Arab world. The rates of

MRSA varied depending on the country and center. A significant spread

of MRSA in some Arab communities was evident by the high nasal MRSA

carriage rate among healthy outpatients, hospital visitors, or

university students seen in certain cities.[12,21-23] As expected, HCWs had higher nasal MRSA rates.[15,19,21,22,25,30]In the clinical setting, methicillin resistance was highly prevalent among clinical isolates of S. aureus in the region.[4,11,42,45-53,56-59,61,71,85]

Thus, while some countries like UAE, Lebanon, Qatar, and Tunisia showed

lower cumulative rates compared to others, there is still evidence of a

high burden in some centers within these countries. Regional variability in MRSA rates has been detected in other areas of the world, such as Europe.[3,11,86]

In the Arab world, this variance in rates could be due to differences

in antibiotic prescribing practices and infection control efforts

across the region and within each country. Additionally, Arab countries

of the Levant and North Africa have suffered decades of economic and

political instability, which negatively impacted medical resources and

healthcare infrastructure instead of the prospering Arab countries in

the GCC region. This could explain the lower rates seen in UAE and

Qatar. Nonetheless, such a theory is challenged by the high MRSA rates

seen in KSA. Perhaps these factors are offset by other determinants in

KSA. Certain

genotypes were particularly prevalent in the Arab world, many of which

belonged to 5 CCs known to spread worldwide. These were previously

discussed in table 1. This is

not surprising given that the Arab World is a center for multinational

ex-pats seeking jobs abroad. Furthermore, KSA is the home of al-Kaʿbah

al-Musharrafah, the destination of Muslim pilgrimage, where masses of

Muslims from across the globe crowd up every year to perform religious

rituals. These crowded conditions are likely to facilitate the spread

of various MRSA strains. Three

clones were particularly important: European CA-MRSA, UK-EMRSA-15

HA-MRSA, and Brazilian/Hungarian HA-MRSA. Genotypes linked to these

clones were distributed across the region. Notably, HA-MRSA clones

might be decreasing in prevalence in some centers while CA-MRSA takes

over. With time, a shift in clonal distribution was noted in Kuwait and

UAE, where CA-MRSA genotypes became more prevalent.[69,71,73,84]

In Kuwait, this was clearly seen in 3 studies examining large samples

from several hospitals across the country from 1992 to 2016.[69,73,84]

This is particularly true of the European CA-MRSA, which was detected

in almost all cited studies and often accounted for a significant

proportion of the study sample. Hence, this clone or its related

strains seem to be infiltrating into the Arab world. Nonetheless, the

presence of HA-MRSA clones remained strong in many studies, including

both the Brazilian/Hungarian clone and the UK-EMRSA-15 clone. USA300

CA-MRSA is another important clone that made up the bulk of isolates in

Iraq's CSHs. However, the subjects here were U.S. military personnel

and might have been colonized prior to being deployed. Hence this might

not be reflective of the Iraqi population.It

is important to acknowledge distinguishing features when comparing

local strains with these epidemic/pandemic clones. Strains from the

Arab world have distinguishing antimicrobial resistance, SCCmec

subtypes, and virulence factors.[82] This was

highlighted briefly during our discussion of CC22 in section Clonal

complex 22. Another distinction was previously made between

ST80-SCCmec-IV strains from the Arab world and the European CA-MRSA

clone.[81,82] The European CA-MRSA is known to be

[PVL+] and resistant to tetracycline, streptomycin, kanamycin, and

fusidic acid (TSKF profile).[81] Overall, only 16% of the ST80 isolates recovered from Lebanon and Jordan had this profile.[81]

A more commonly detected pattern in both countries included resistance

to streptomycin, kanamycin, and fusidic acid (SKF pattern).[81]

Phenotypical variation between the Kuwaiti ST80 isolates and the

European CA-MRSA clone was pointed out, particularly regarding some

differences in antimicrobial resistance patterns and enterotoxin gene

profiles.[82] PFGE analysis of ST80 isolates from a

subset of these hospitals in Kuwait showed that a large proportion was

related but not identical, further pointing out the heterogeneity among

local strains.[82] This was mirrored in another study

from Kuwait, which identified 102 novel variants of previously known

genotypes reported locally and worldwide.[73]

Furthermore, it was shown that isolates derived from different regions

in the Arab world could have a heterogeneous lineage despite belonging

to the same Spa-clonal complex.[81] These findings raise the possibility that local strains might have polyphyletic origins.Our

review provides a comprehensive summary of the available literature on

the epidemiology of MRSA in the MENA. Multiple important points were

highlighted. Nonetheless, our work is not without limitations. Most

studies in our review were single-centered reports, limiting our

ability to uncover the full burden of MRSA. Furthermore, there was

significant heterogeneity in molecular typing methods and reporting of

results, which hinders our ability to compare between different centers

or countries in the region. Furthermore, the bulk of studies did not

distinguish between CO-MRSA and HO-MRSA based on epidemiological

criteria, and so we are unable to accurately distinguish the

epidemiology of MRSA in the community vs. healthcare setting.

Conclusion

This

manuscript provides a review of the current literature on MRSA

epidemiology in Arab countries. There is enough evidence to suggest

that the Arab region struggles from a heavy MRSA burden. Genotypes associated with

European CA-MRSA play the biggest role, but Brazilian/Hungarian HA-MRSA

and UK-EMRSA-15 HA-MRSA are also prevalent. Therefore, the Arab

countries need to implement a nationwide surveillance system to

understand better the true epidemiology and burden of MRSA in this part

of the world.

References

- Deurenberg, R.H., et al., The molecular evolution

of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Microbiol Infect,

2007. 13(3): p. 222-35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01573.x

- Grundmann,

H., et al., Emergence and resurgence of meticillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus as a public-health threat. Lancet, 2006.

368(9538): p. 874-85. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68853-3

- Borg,

M.A., et al., Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

(MRSA) in invasive isolates from southern and eastern Mediterranean

countries. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2007. 60(6): p. 1310-5. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkm365

- Yousef

SA, Mahmoud SY, and E. MT., PREVALENCE OF METHICILLIN-RESISTANT

STAPHYLOCOCCUS AUREUS IN SAUDI ARABIA: SYSTEMIC REVIEW AND

META-ANALYSIS. . 2013: Afr J Cln Exper Microbiol. p. 146-54.

- "Middle East & North Africa | Data". Data.Worldbank.Org , 2021, https://data.worldbank.org/country/ZQ.

- Udo,

E.E., D. Panigrahi, and A.E. Jamsheer, Molecular typing of

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated in a Bahrain

hospital. Med Princ Pract, 2008. 17(4): p. 308-14. https://doi.org/10.1159/000129611

- Alfouzan,

W., et al., Molecular Characterization of Methicillin- Resistant

Staphylococcus aureus in a Tertiary Care hospital in Kuwait. Sci Rep,

2019. 9(1): p. 18527. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-54794-8

- Monecke,

S., et al., A field guide to pandemic, epidemic and sporadic clones of

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS One, 2011. 6(4): p.

e17936. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0017936

- Liu, G.Y., Molecular pathogenesis of Staphylococcus aureus infection. Pediatr Res, 2009. 65(5 Pt 2): p. 71R-77R. https://doi.org/10.1203/PDR.0b013e31819dc44d

- Lina,

G., et al., Involvement of Panton-Valentine leukocidin-producing

Staphylococcus aureus in primary skin infections and pneumonia. Clin

Infect Dis, 1999. 29(5): p. 1128-32. https://doi.org/10.1086/313461

- El-Mahdy,

T.S., M. El-Ahmady, and R.V. Goering, Molecular characterization of

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated over a 2-year

period in a Qatari hospital from multinational patients. Clin Microbiol

Infect, 2014. 20(2): p. 169-73. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-0691.12240

- Abou

Shady, H.M., et al., Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage among

outpatients attending primary health care centers: a comparative study

of two cities in Saudi Arabia and Egypt. Brazilian Journal of

Infectious Diseases, 2015. 19(1): p. 68-76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjid.2014.09.005

- Panhotra,

B.R., A.K. Saxena, and A.S. Al Mulhim, Prevalence of

methicillin-resistant and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus

nasal colonization among patients at the time of admission to the

hospital. Ann Saudi Med, 2005. 25(4): p. 304-8. https://doi.org/10.5144/0256-4947.2005.304

- Alhussaini,

M.S., Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus Nasal Carriage Among

Patients Admitted at Shaqra General Hospital in Saudi Arabia. Pak J

Biol Sci, 2016. 19(5): p. 233-238. https://doi.org/10.3923/pjbs.2016.233.238

- Iyer,

A., et al., High incidence rate of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus

aureus (MRSA) among healthcare workers in Saudi Arabia. J Infect Dev

Ctries, 2014. 8(3): p. 372-8. https://doi.org/10.3855/jidc.3589

- El-Mahdy,

T.S., et al. Complex Clonal Diversity of Staphylococcus aureus Nasal

Colonization among Community Personnel, Healthcare Workers, and

Clinical Students in the Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia. Biomed Res

Int, 2018. 2018: p. 4208762. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/4208762

- Zakai,

S.A., Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nasal

colonization among medical students in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med

J, 2015. 36(7): p. 807-12. https://doi.org/10.15537/smj.2015.7.11609

- Ghanem,

H.M., A.M. Abou-Alia, and S.A. Alsirafy, Prevalence of

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization and infection

in hospitalized palliative care patients with cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat

Care, 2013. 30(4): p. 377-9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909112452335

- Al-Humaidan,

O.S., T.A. El-Kersh, and R.A. Al-Akeel, Risk factors of nasal carriage

of Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus

aureus among health care staff in a teaching hospital in central Saudi

Arabia. Saudi Med J, 2015. 36(9): p. 1084-90. https://doi.org/10.15537/smj.2015.9.12460

- Alfouzan,

W., R. Dhar, and E. Udo, Genetic Lineages of Methicillin-Resistant

Staphylococcus aureus Acquired during Admission to an Intensive Care

Unit of a General Hospital. Med Princ Pract, 2017. 26(2): p. 113-117. https://doi.org/10.1159/000453268

- Pathare,

N.A., et al., Comparison of Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus

in Healthy Community Hospital Visitors [CA-MRSA] and Hospital Staff

[HA-MRSA]. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis, 2015. 7(1): p. e2015053. https://doi.org/10.4084/mjhid.2015.053

- Pathare,

N.A., et al., Prevalence of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus

[MRSA] colonization or carriage among healthcare workers. J Infect

Public Health, 2016. 9(5): p. 571-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2015.12.004

- Biber,

A., et al., A typical hospital-acquired methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus clone is widespread in the community in the Gaza

strip. PLoS One, 2012. 7(8): p. e42864. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0042864

- Kaibni,

M.H., et al., Community-acquired meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus

aureus in Palestine. J Med Microbiol, 2009. 58(Pt 5): p. 644-7. https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.007617-0

- El

Aila, N.A., N.A. Al Laham, and B.M. Ayesh, Nasal carriage of

methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus among health care workers

at Al Shifa hospital in Gaza Strip. Bmc Infectious Diseases, 2017. 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-016-2139-1

- Al-Bakri,

A.G., et al., The epidemiology and molecular characterization of

methicillin-resistant staphylococci sampled from a healthy Jordanian

population. Epidemiol Infect, 2013. 141(11): p. 2384-91. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268813000010

- Aqel,

A.A., et al., Molecular epidemiology of nasal isolates of

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from Jordan. J Infect

Public Health, 2015. 8(1): p. 90-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2014.05.007

- Sfeir,

M., et al., Prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus methicillin-sensitive

and methicillin-resistant nasal and pharyngeal colonization in

outpatients in Lebanon. Am J Infect Control, 2014. 42(2): p. 160-3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2013.08.008

- Halablab,

M.A., et al., Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage rate and associated

risk factors in individuals in the community. Epidemiol Infect, 2010.

138(5): p. 702-6. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268809991233

- Hussein,

N.R., M.S. Assafi, and T. Ijaz, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus

aureus nasal colonisation amongst healthcare workers in Kurdistan

Region, Iraq. J Glob Antimicrob Resist, 2017. 9: p. 78-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgar.2017.01.010

- Khairalla,

A.S., R. Wasfi, and H.M. Ashour, Carriage frequency, phenotypic, and

genotypic characteristics of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus

aureus isolated from dental healthcare personnel, patients, and

environment. Sci Rep, 2017. 7(1): p. 7390. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-07713-8

- Abaza,

A.F., et al., Nasal carriage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus

aureus and the effect of tea extracts on isolates. J Egypt Public

Health Assoc, 2016. 91(3): p. 135-143. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.EPX.0000491266.22392.c3

- Hefzy,

E.M., G.M. Hassan, and F. Abd El Reheem, Detection of Panton-Valentine

Leukocidin-Positive Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Nasal

Carriage among Egyptian Health Care Workers. Surg Infect (Larchmt),

2016. 17(3): p. 369-75. https://doi.org/10.1089/sur.2015.192

- Djoudi,

F., et al., Descriptive epidemiology of nasal carriage of

Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

among patients admitted to two healthcare facilities in Algeria. Microb

Drug Resist, 2015. 21(2): p. 218-23. https://doi.org/10.1089/mdr.2014.0156

- Antri, K., et al., High levels

of Staphylococcus aureus and MRSA carriage in healthy population of

Algiers revealed by additional enrichment and multisite screening. Eur

J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, 2018. 37(8): p. 1521-1529. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-018-3279-6

- Ben

Slama, K., et al., Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus in healthy

humans with different levels of contact with animals in Tunisia:

genetic lineages, methicillin resistance, and virulence factors. Eur J

Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, 2011. 30(4): p. 499-508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-010-1109-6

- Eed,

E.M., et al., Molecular characterisation of Panton-Valentine

leucocidin-producing methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones

isolated from the main hospitals in Taif, KSA. Indian J Med Microbiol,

2016. 34(4): p. 476-482. https://doi.org/10.4103/0255-0857.195364

- Asghar,

A.H., Molecular characterization of methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus isolated from tertiary care hospitals. Pak J Med

Sci, 2014. 30(4): p. 698-702. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.304.4946

- Haseeb,

A., et al., Antimicrobial resistance among pilgrims: a retrospective

study from two hospitals in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. Int J Infect Dis,

2016. 47: p. 92-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2016.06.006

- Abdel-Fattah,

M.M., Surveillance of nosocomial infections at a Saudi Arabian military

hospital for a one-year period. Ger Med Sci, 2005. 3: p. Doc06.

- Al

Jalaf, M., et al., Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus Aureus in

emergency department patients in the United Arab Emirates. BMC Emerg

Med, 2018. 18(1): p. 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-018-0164-7

- Al-Yaqoubi,

M. and K. Elhag, Susceptibilities of common bacterial isolates from

oman to old and new antibiotics. Oman Med J, 2008. 23(3): p. 173-8.

- Al

Rahmany, D., et al., Exploring bacterial resistance in Northern Oman, a

foundation for implementing evidence-based antimicrobial stewardship

program. Int J Infect Dis, 2019. 83: p. 77-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2019.04.004

- Khan,

F.Y., et al., Epidemiology of bacteraemia in Hamad general hospital,

Qatar: a one year hospital-based study. Travel Med Infect Dis, 2010.

8(6): p. 377-87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2010.10.004

- Al

Laham, N., et al., MRSA clonal complex 22 strains harboring toxic shock

syndrome toxin (TSST-1) are endemic in the primary hospital in Gaza,

Palestine. PLoS One, 2015. 10(3): p. e0120008. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0120008

- Al-Zoubi,

M.S., et al., Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of Staphylococcus

aureus isolated from clinical specimens in Northern area of Jordan.

Iran J Microbiol, 2015. 7(5): p. 265-72.

- Bazzoun,

D.A., et al., Molecular typing of Staphylococcus aureus collected from

a Major Hospital in Amman, Jordan. J Infect Dev Ctries, 2014. 8(4): p.

441-7. https://doi.org/10.3855/jidc.3676

- Tokajian,

S.T., et al., Molecular characterization of Staphylococcus aureus in

Lebanon. Epidemiol Infect, 2010. 138(5): p. 707-12. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268810000440

- Chamoun,

K., et al., Surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in Lebanese

hospitals: retrospective nationwide compiled data. Int J Infect Dis,

2016. 46: p. 64-70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2016.03.010

- Araj,

G.F., et al., A reflection on bacterial resistance to antimicrobial

agents at a major tertiary care center in Lebanon over a decade. J Med

Liban, 2012. 60(3): p. 125-35.

- Co, E.M.,

E.F. Keen, 3rd, and W.K. Aldous, Prevalence of methicillin-resistant

staphylococcus aureus in a combat support hospital in Iraq. Mil Med,

2011. 176(1): p. 89-93. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-09-00126

- Roberts,

S.S. and R.J. Kazragis, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

infections in U.S. service members deployed to Iraq. Mil Med, 2009.

174(4): p. 408-11. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-02-8408

- Babakir-Mina,

M., et al., Antibiotic susceptibility of vancomyin and nitrofurantoin

in Staphylococcus aureus isolated from burnt patients in Sulaimaniyah,

Iraqi Kurdistan. New Microbiol, 2012. 35(4): p. 439-46.

- Abd

El-Hamid, M.I. and M.M. Bendary, Comparative phenotypic and genotypic

discrimination of methicillin resistant and susceptible Staphylococcus

aureus in Egypt. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand), 2015. 61(4): p.

101-12.

- Bendary, M.M., et al.,

Characterization of Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus

isolated from human and animal samples in Egypt. Cell Mol Biol

(Noisy-le-grand), 2016. 62(2): p. 94-100.

- Sobhy,

N., et al., Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus

aureus from skin and soft tissue infections (in a sample of Egyptian

population): analysis of mec gene and staphylococcal cassette

chromosome. Braz J Infect Dis, 2012. 16(5): p. 426-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjid.2012.08.004

- Abdel-Maksoud,

M., et al., Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Recovered from

Healthcare- and Community-Associated Infections in Egypt. Int J

Bacteriol, 2016. 2016: p. 5751785. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/5751785

- Alioua,

M.A., et al., Emergence of the European ST80 clone of

community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus as a

cause of healthcare-associated infections in Eastern Algeria. Med Mal

Infect, 2014. 44(4): p. 180-3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medmal.2014.01.006

- Djoudi,

F., et al., Panton-Valentine leukocidin positive sequence type 80

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carrying a staphylococcal

cassette chromosome mec type IVc is dominant in neonates and children

in an Algiers hospital. New Microbiol, 2013. 36(1): p. 49-55.

- Djahmi,

N., et al., Molecular epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus strains

isolated from inpatients with infected diabetic foot ulcers in an

Algerian University Hospital. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2013. 19(9): p.

E398-404. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-0691.12199

- Antri,

K., et al., High prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus

aureus clone ST80-IV in hospital and community settings in Algiers.

Clin Microbiol Infect, 2011. 17(4): p. 526-32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03273.x

- Rebiahi,

S.A., et al., Emergence of vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

identified in the Tlemcen university hospital (North-West Algeria). Med

Mal Infect, 2011. 41(12): p. 646-51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medmal.2011.09.010

- Bouchami,

O., W. Achour, and A. Ben Hassen, Typing of staphylococcal cassette

chromosome mec encoding methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus

strains isolated at the bone marrow transplant centre of Tunisia. Curr

Microbiol, 2009. 59(4): p. 380-5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00284-009-9448-1

- Mesrati,

I., et al., Clinical isolates of Pantone-Valentine leucocidin- and

gamma-haemolysin-producing Staphylococcus aureus: prevalence and

association with clinical infections. J Hosp Infect, 2010. 75(4): p.

265-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2010.03.015

- Elhani,

D., et al., Clonal lineages detected amongst tetracycline-resistant

meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates of a Tunisian

hospital, with detection of lineage ST398. J Med Microbiol, 2015.

64(6): p. 623-9. https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.000066

- Alreshidi,

M.A., et al., Genetic variation among methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus isolates from cancer patients in Saudi Arabia.

Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, 2013. 32(6): p. 755-61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-012-1801-9

- Monecke,

S., et al., Characterisation of MRSA strains isolated from patients in

a hospital in Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. BMC Microbiol, 2012. 12:

p. 146. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-12-146

- Senok,

A., et al., Molecular characterization of methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus in nosocomial infections in a tertiary-care

facility: emergence of new clonal complexes in Saudi Arabia. New

Microbes New Infect, 2016. 14: p. 13-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmni.2016.07.009

- Boswihi,

S.S., E.E. Udo, and N. Al-Sweih, Shifts in the Clonal Distribution of

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Kuwait Hospitals:

1992-2010. PLoS One, 2016. 11(9): p. e0162744. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0162744

- Udo,

E.E., et al., Genetic lineages of community-associated

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Kuwait hospitals. J Clin

Microbiol, 2008. 46(10): p. 3514-6. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00966-08

- Sonnevend

Á, B.I., Alkaabi M, Jumaa P, Al Haj M, Ghazawi A, Akawi N, Jouhar FS,

Hamadeh MB, Pál T., Change in meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus

aureus clones at a tertiary care hospital in the United Arab Emirates

over a 5-year period. J Clin Pathol. , 2012. 65(2): p. 178-82. https://doi.org/10.1136/jclinpath-2011-200436

- Moussa,

I., et al., A novel multiplex PCR for molecular characterization of

methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus recovered from Jeddah,

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Indian J Med Microbiol, 2012. 30(3): p.

296-301. https://doi.org/10.4103/0255-0857.99490

- Boswihi,

S.S., et al., Emerging variants of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus

aureus genotypes in Kuwait hospitals. PLoS One, 2018. 13(4): p.

e0195933. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195933

- Huang,

X.Z., et al., Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection in

combat support hospitals in three regions of Iraq. Epidemiol Infect,

2011. 139(7): p. 994-7. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268810001950

- Basset,

P., W. Amhis, and D.S. Blanc, Changing molecular epidemiology of

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in an Algerian hospital. J

Infect Dev Ctries, 2015. 9(2): p. 206-9. https://doi.org/10.3855/jidc.4620

- Ouchenane,

Z., et al., Molecular characterization of methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus isolates in Algeria. Pathol Biol (Paris), 2011.

59(6): p. e129-32.

- Mariem, B.J., et al.,

Molecular characterization of methicillin-resistant Panton-valentine

leukocidin positive staphylococcus aureus clones disseminating in

Tunisian hospitals and in the community. BMC Microbiol, 2013. 13: p. 2.

https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-13-2

- Udo,

E.E., S.S. Boswihi, and N. Al-Sweih, High prevalence of toxic shock

syndrome toxin-producing epidemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus

aureus 15 (EMRSA-15) strains in Kuwait hospitals. New Microbes New

Infect, 2016. 12: p. 24-30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmni.2016.03.008

- Harastani,

H.H., G.F. Araj, and S.T. Tokajian, Molecular characteristics of

Staphylococcus aureus isolated from a major hospital in Lebanon. Int J

Infect Dis, 2014. 19: p. 33-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2013.10.007

- Senok,

A., et al., Diversity of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

CC22-MRSA-IV from Saudi Arabia and the Gulf region. Int J Infect Dis,

2016. 51: p. 31-35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2016.08.016

- Harastani,

H.H. and S.T. Tokajian, Community-associated methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus clonal complex 80 type IV (CC80-MRSA-IV) isolated

from the Middle East: a heterogeneous expanding clonal lineage. PLoS

One, 2014. 9(7): p. e103715. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0103715

- Udo,

E.E. and E. Sarkhoo, The dissemination of ST80-SCCmec-IV

community-associated methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone

in Kuwait hospitals. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob, 2010. 9: p. 31. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-0711-9-31

- Moussa,

I. and A.M. Shibl, Molecular characterization of methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus recovered from outpatient clinics in Riyadh,

Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J, 2009. 30(5): p. 611-7.

- Udo,

E.E. and S.S. Boswihi, Antibiotic Resistance Trends in

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Isolated in Kuwait

Hospitals: 2011-2015. Med Princ Pract, 2017. 26(5): p. 485-490. https://doi.org/10.1159/000481944

- Baddour,

M.M., M.M. Abuelkheir, and A.J. Fatani, Trends in antibiotic

susceptibility patterns and epidemiology of MRSA isolates from several

hospitals in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob, 2006.

5: p. 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-0711-5-30

- Tiemersma,

E.W., et al., Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Europe,

1999-2002. Emerg Infect Dis, 2004. 10(9): p. 1627-34. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1009.040069

Supplementary files

|

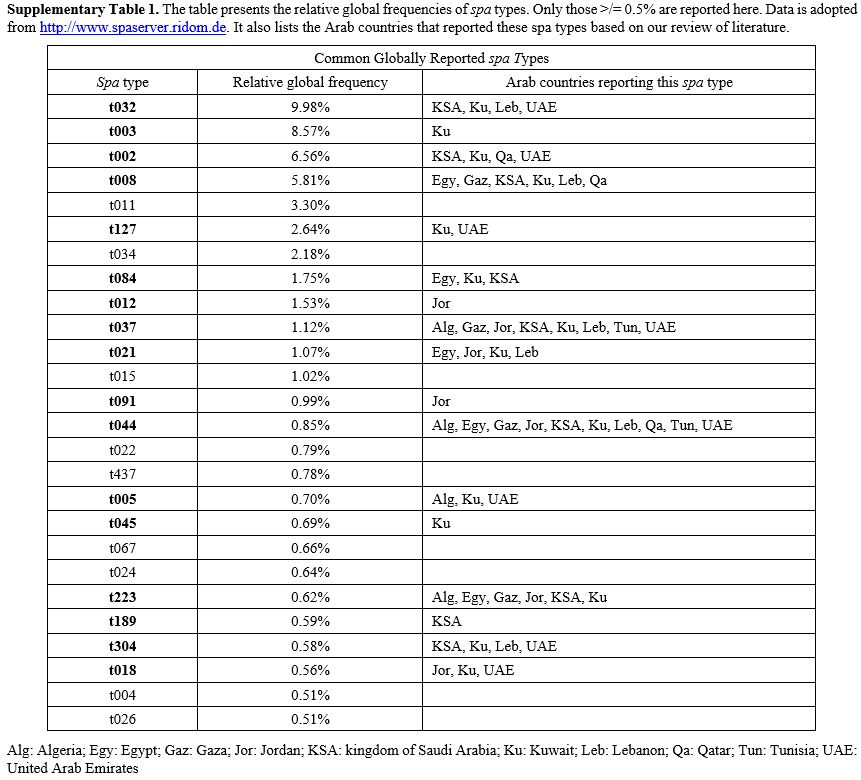

Supplementary Table 1. The

table presents the relative global frequencies of spa types. Only those

>/= 0.5% are reported here. Data is adopted from

http://www.spaserver.ridom.de. It also lists the Arab countries that

reported these spa types based on our review of literature.

|

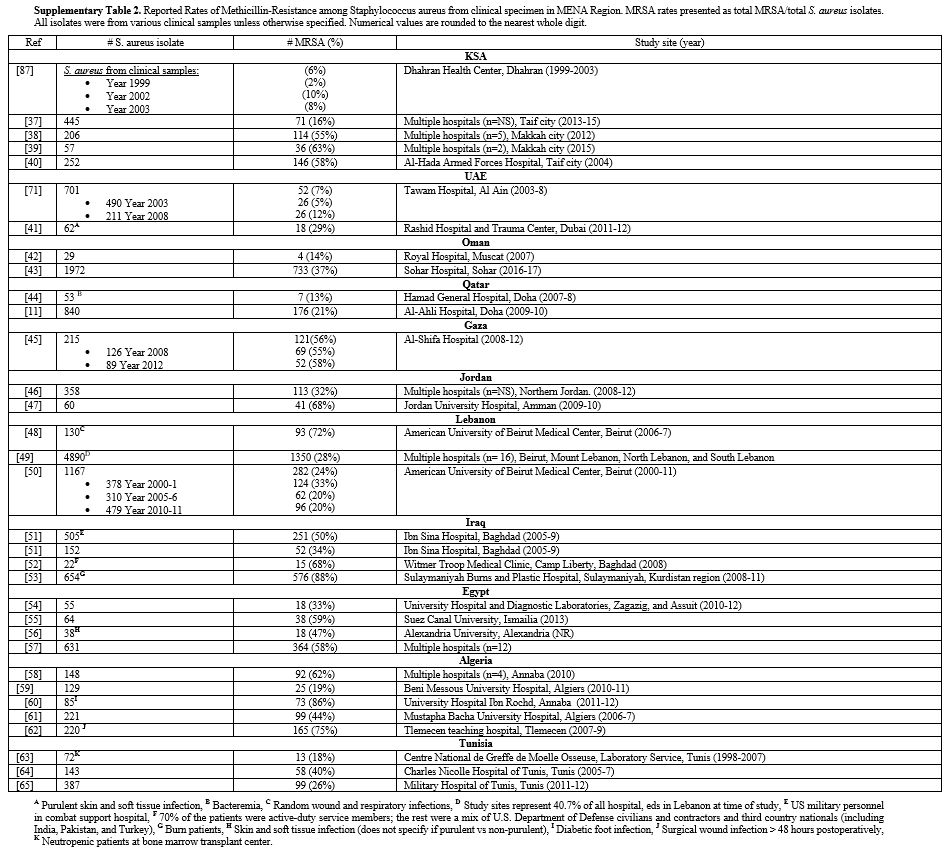

|

Supplementary Table

2. Reported Rates of Methicillin-Resistance among Staphylococcus

aureus from clinical specimen in MENA Region. MRSA rates presented as

total MRSA/total S. aureus isolates. All isolates were from

various clinical samples unless otherwise specified. Numerical values

are rounded to the nearest whole digit.

|

|

Supplementary Table 3. Molecular Typing of

Colonizing MRSA Strains in the MENA Region. Numerical values are

rounded to the nearest whole digit. |

|

Supplementary Table 4.Molecular Typing of Infective MRSA Isolates in the MENA Region. |

|

Supplementary Table 5. Antimicrobial

Susceptibility Profile of MRSA Isolates in the Arab World. Presented

values are percentages of tested isolates. Infective isolates are

labeled as CO-MRSA or HO-MRSA when specified by the cited study,

otherwise they are labeled as Not specified. |

|

Supplementary Figure 1. Illustrates how different typing techniques can be grouped together into a clonal complex.

|

[TOP]