Gabriele Magliano1, Annarosa Cuccaro3, Francesco d’Alo’1,2, Elena Maiolo2, Silvia Bellesi2, Stefan Hohaus1,2, Andrea Bacigalupo1,2, Livio Pagano1,2.

1Sezione di Ematologia, Dipartimento di Scienze Radiologiche ed Ematologiche, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Roma

2

Dipartimento di Diagnostica per Immagini, Radioterapia Oncologica ed

Ematologia, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS, Roma;

3 UOC Ematologia Aziendale, Azienda Toscana Nord-Ovest, Livorno, Italy.

Correspondence to:

Gabriele Magliano. Sezione di Ematologia, Dipartimento di Scienze

Radiologiche ed Ematologiche, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore,

Roma.

Published: September 1, 2021

Received: May 26, 2021

Accepted: August 7, 2021

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2021, 13(1): e2021054 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2021.054

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

To the editor

We

discuss the case of a 74-year old male patient with mantle cell

lymphoma, who faced severe cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection after the

fifth cycle of first-line chemo-immunotherapy with a dose-reduced

bendamustine and rituximab regimen.

The patient came to our

attention in May 2017. He reported weight loss of 10% and night

sweats in the previous two months; his performance was reduced (ECOG

3). His past medical history was unremarkable.

Bone marrow

biopsy revealed a pleomorphic variant of mantle cell lymphoma. The

stage was IVB (superior and inferior nodal site involvement, B

symptoms). MIPI score was 9.4 (high risk): age 74 years, LDH 3116 UI/L,

WBCs 3.01 x10^9/L, ECOG 3, Ki67 85% on histology.

At

diagnosis, CD4 count was 0.24x10^9/L (0.63-1.4), with inversion of

CD4/CD8 ratio. There were no other detectable causes of immune

suppression.

Considering age and performance status, we started chemo-immunotherapy with rituximab (375 mg/m2 on day 2)-bendamustine (70 mg/m2 on day 1-2) every 28 days. As a common clinical practice, we did not perform antiviral prophylaxis.

Two

weeks after the fifth cycle, the patient was admitted to our hospital

with fever (38.5 °C), dyspnea, and diarrhea. Chest X-ray revealed

interstitial pneumonitis with bilateral basal thickening and left

pleural effusion. Thoracic CT scan showed pulmonary edema with diffuse

ground-glass opacities, bilateral pleural effusions, and small

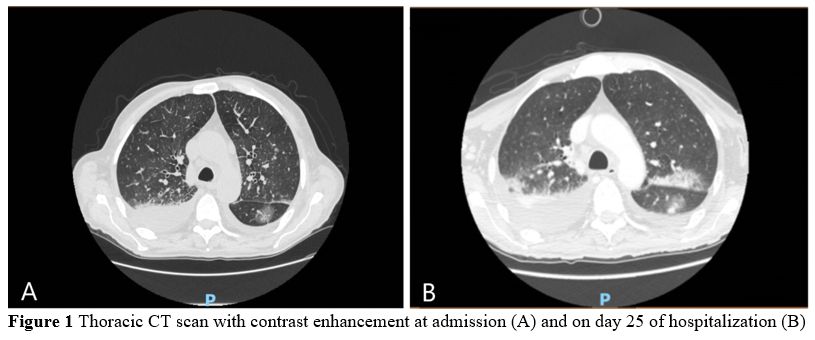

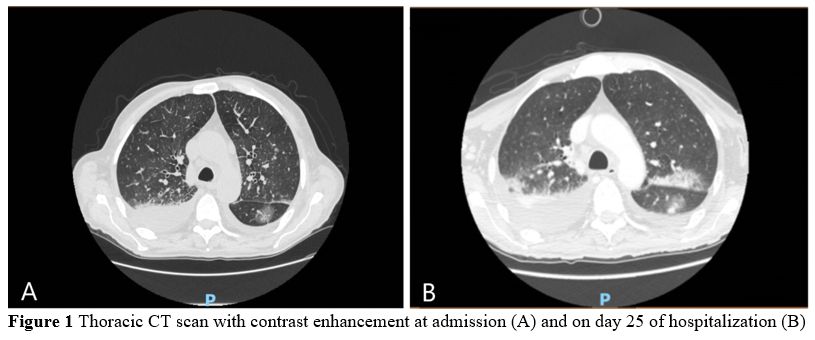

pericardial effusion of 8 mm (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1. Thoracic CT scan with contrast enhancement at admission (A) and on day 25 of hospitalization (B). |

Hemoglobin

levels were 8.1 g/dL, WBCs were 2.37x10^9/L, plts were 55x10^9/L.

Intravenous antibiotic therapy with piperacillin-tazobactam and

levofloxacin and oxygen support was started. Unfortunately, fever

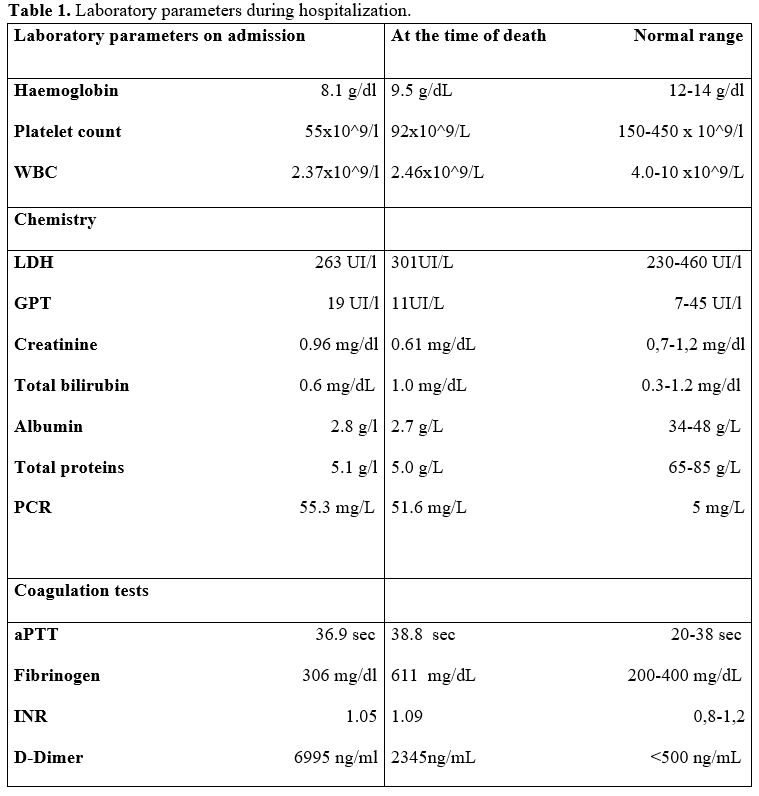

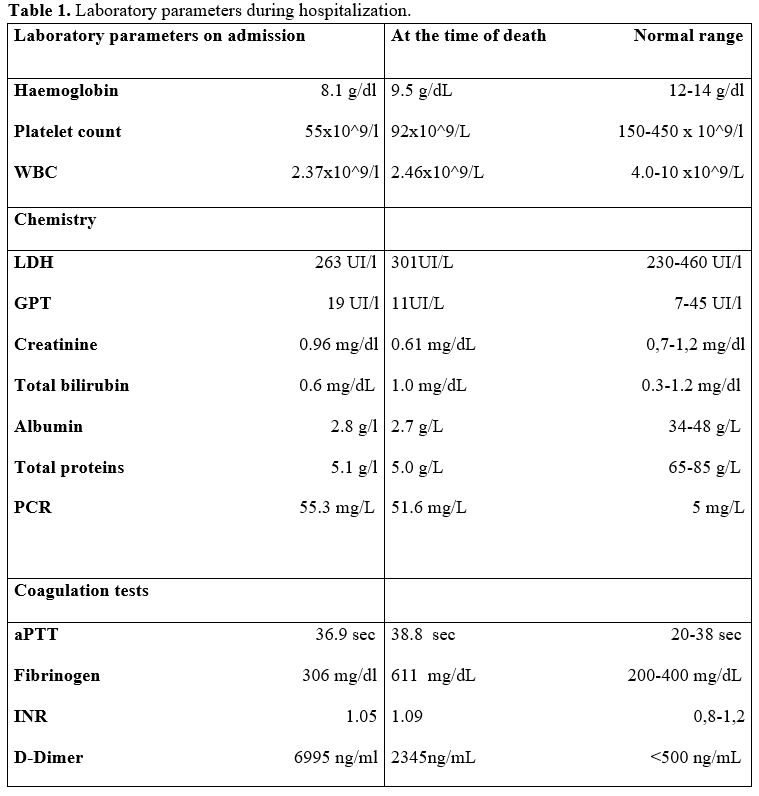

persisted with no clinical improvement (Table 1).

|

Table 1. Laboratory parameters during hospitalization. |

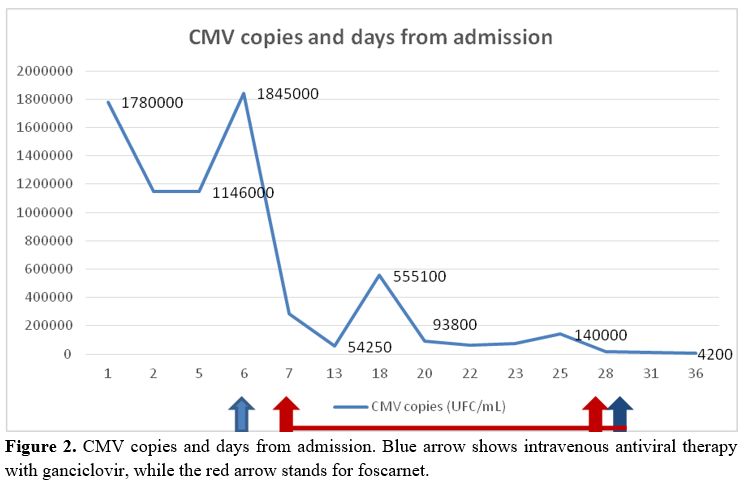

On

the sixth day of hospitalization blood PCR test for CMV yielded

1,400,000 copies/mL, and intravenous antiviral therapy with ganciclovir

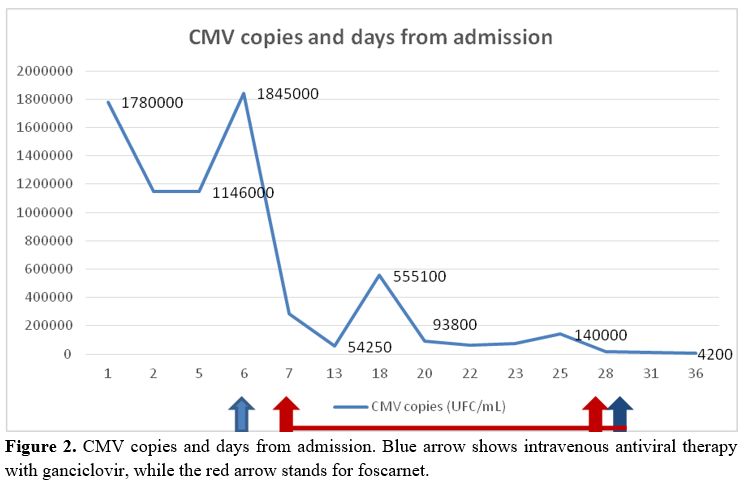

5 mg/Kg bid was started (Figure 2).

|

Figure

2. CMV copies and days from admission. Blue arrow shows intravenous

antiviral therapy with ganciclovir, while the red arrow stands for

foscarnet. |

After

one day of antiviral therapy, the patient developed neurological

symptoms with paresthesia and tremor. For the suspect of an adverse

drug effect to ganciclovir, antiviral treatment was modified to

foscarnet 20 mg/Kg.

Despite antiviral therapy, clinical conditions

kept worsening, as the patient required increased oxygen support and

remained febrile. CT scan of the thorax performed on day 25 revealed

new ground-glass opacities in the superior pulmonary lobes. In

addition, pericardial effusion increased to 13 mm (Figure 1).

Microbiological

examination of bronchoalveolar lavage yielded 54,250 copies of

CMV-DNA/ml bronchoalveolar fluid, 462 pg/ml of Candida antigen, and 0.7

pg/mL Aspergillus spp. In addition, intravenous antifungal therapy with

voriconazole was added.

CMV copy number in peripheral blood

remained high (140,000/mmc), and antiviral therapy was changed to

ganciclovir on day 29 of hospital admission. Lymphocyte counts

decreased: CD4+ cells, 0.042 x 10^9/L (0.63-1.40), CD8, 0.12 x 10^9/L

(0.35-0.81), CD56+, 0.093 x 10^9/L (0.14-0.42), and CD19 cells were

undetectable. After another six days, the patient developed psychomotor

agitation. Antiviral therapy was stopped. The patient died after two

other days of hospitalization.

Discussion

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) primarily occurs among elderly patients with a median age greater than 60 years.[1]

Half of these patients are not eligible for standard therapy that

includes autologous blood stem cell transplantation due to the presence

of comorbidities and to the general performance status.

Bendamustine-rituximab

(BR) is currently becoming the treatment of choice in older patients

with indolent non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) and MCL,[2,3] having a favorable toxicity profile.[2]

However,

the BR combination has been shown to cause myelosuppression, including

combined T and B cell lymphopenia, with more profound T cell depletion.[4]

In addition, Saito and colleagues observed that the median lymphocyte

and CD4+ T-cell count decreased significantly after the first

administration of bendamustine in patients with relapsed or refractory

indolent B-NHL.[5]

Infection rates in patients

receiving bendamustine in randomized, controlled clinical trials range

from 6% to 55%, with 1% to 35% of them being grade 3 to 4.[4]

CD4+ recovery after BR is often delayed and consequently correlated

with the risk of any type of infection. Time to recovery to

pre-treatment values ranges from 7-9 months[5] to more

than two years after the last administration. In addition, low

end-of-treatment absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) and a total dose of

bendamustine higher than 1080 mg/m2 have been reported to predict delayed CD4+ recovery.[6]

Receiving

bendamustine as part of later lines of therapy (third-line and above

treatment) has been identified as another risk factor for infections.[7,8]

This

impairment in T cell immunity has been shown to trigger, in particular,

CMV reactivation. For example, in the study by Saito, CMV antigenemia

was detected in 15 of 56 patients (27%) and CMV colitis in 1 patient.

All these events occurred within nine months after completion of

treatment.[5,8,9]

In a recent

real-world study on 167 NHL, age ≥ 60 was a risk factor for CMV

reactivation in patients treated with first-line bendamustine.[10]

Another

report by Cona and colleagues described a severe, disseminated form of

CMV reactivation in a 75-year-old lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma patient,

who faced a profound imbalance in phenotype and function of B-and

T-cell subsets after BR.[11]

Our case highlights

how severe CMV reactivation can occur in the elderly MCL patient

treated with bendamustine, even when administered at a lower dose (our

patient had received a total of 700 mg) and as part of

first-line therapy.

Our patient presented with low CD4+ cell

counts (0.24x10^9/L) at diagnosis, before starting treatment, without

having other detectable causes of immune suppression (e.g.,

co-infections).

Age-related changes in the immune system,

collectively called immunosenescence, in addition to immune suppression

correlated with the underlying disease, might have contributed to

CMV reactivation after BR.

Despite treatment with ganciclovir

and foscarnet, CMV pneumonitis did not resolve, and immune suppression

was persistent, as CD4+ cells were 0.042x10^9/L on day 22.

We

could not assess if CMV pneumonia was the single main cause of death,

as an autopsy could not be performed. However, considering the

significant worsening of the clinical conditions (together with the

radiological picture), we believe it contributed to the dismal outcome.

Lymphocyte

profiling and monitoring ALC and CD4+ count before, during, and

after the end of treatment could help to identify patients who might be

at particular risk of delayed CD4+ recovery and consequently of viral

and opportunistic infectious complications.[6]

A

low CD4+ count could be a trigger to monitor also CMV DNA. However,

studies are needed to assess the effectiveness of a pre-emptive

antiviral therapy in this context, as recommended in 2017 by the UK

Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA).[12]

A

recent study by Fung and colleagues estimated that antiviral

prophylaxis could prevent one CMV case every 269

bendamustine-treated patients with NHL.[7]

In our

case, bronchoalveolar lavage detected a concomitant fungal infection,

although CT of the thorax was suggestive for CMV pneumonia. Neutropenia

was an additional risk factor for fungal infection.

In an Israeli

retrospective analysis, the frequency of fungal infections in 183

patients affected by lymphoproliferative neoplasms and treated with a

bendamustine-containing regimen was 3.8%.[13]

In the study by Fung, bendamustine treatment was associated with a higher incidence of neutropenia and candida infection.[7]

Conclusions

Our

case is an alert for clinicians that BR can be associated with severe

infections in elderly patients even in first-line therapy at a reduced

dose. However, as BR is otherwise well tolerated, the infectious risk

should not be underestimated in the presence of an overall low burden

of side effects.

Randomized prospective studies are required to

assess the efficacy of monitoring, prophylaxis, and pre-emptive therapy

to mitigate the risk of infections, hospital admission, and mortality

in bendamustine-treated patients with NHL. These studies should

consider characteristics of the patient, such as age and immune status,

the type of NHL, the line of treatment, and the addition of other

drugs, including rituximab.

References

- Jares P, Campo E. Advances in the understanding of mantlecell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2008 Jun;142(2):149-65

- Doorduijn JK, Kluin-Nelemans HC. Management of mantle cell lymphoma in the elderly patient. Clin IntervAging. 2013;8:1229-36

- Flinn

IW, van der Jagt R, Kahl BS, Wood P, Hawkins TE, Macdonald D, Hertzberg

M, Kwan YL, Simpson D, Craig M, Kolibaba K, Issa S, Clementi R, Hallman

DM, Munteanu M, Chen L, Burke JM. Randomized trial of

bendamustine-rituximab or R-CHOP/R-CVP in first-line treatment of

indolent NHL or MCL: the BRIGHT study. Blood. 2014 May 8;123(19):2944-52

- Gafter-Gvili

A, Ribakovsky E, Mizrahi N, Avigdor A, Aviv A, Vidal L, Ram R, Perry C,

Avivi I, Kedmi M, Nagler A, Raanani P, Gurion R. Infections associated

with bendamustine containing regimens in hematological patients: a

retrospective multi-center study. Leuk Lymphoma. 2016;57(1):63-9. https://doi.org/10.3109/10428194.2015.1046862

- Saito

H, Maruyama D, Maeshima AM, Makita S, Kitahara H, Miyamoto K, Fukuhara

S, Munakata W, Suzuki T, Kobayashi Y, Taniguchi H, Tobinai K. Prolonged

lymphocytopenia after bendamustine therapy in patients with relapsed or

refractory indolent B-cell and mantle cell lymphoma. Blood Cancer J.

2015 Oct 23;5(10):e362.

- Martínez-Calle N,

Hartley S, Ahearne M, Kasenda B, Beech A, Knight H, Balotis C, Kennedy

B, Wagner S, Dyer MJS, Smith D, McMillan AK, Miall F, Bishton M, Fox

CP. Kinetics of T-cell subset reconstitution following treatment with

bendamustine and rituximab for low-grade lymphoproliferative disease: a

population-based analysis. Br J Haematol. 2019 Mar;184(6):957-968

- Fung

M, Jacobsen E, Freedman A, Prestes D, Farmakiotis D, Gu X, Nguyen PL,

Koo S. Increased Risk of Infectious Complications in Older Patients

With Indolent Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Exposed to Bendamustine. Clin Infect

Dis. 2019 Jan 7;68(2):247-255

- Hasegawa T,

Aisa Y, Shimazaki K, Nakazato T. Cytomegalovirus reactivation with

bendamustine in patients with low-grade B-cell lymphoma. Ann Hematol.

2015 Mar;94(3):515-7

- Hosoda T, Yokoyama

A, Yoneda M et al. bendamustine can severely impair T-cell immunity

against cytomegalovirus. Leuk Lymphoma 2013; 54: 1327-1328. https://doi.org/10.3109/10428194.2012.739285

- Pezzullo

L, Giudice V, Serio B, Fontana R, Guariglia R, Martorelli MC, Ferrara

I, Mettivier L, Bruno A, Bianco R, Vaccaro E, Pagliano P, Montuori N,

Filippelli A, Selleri C. Real-world evidence of cytomegalovirus

reactivation in non-Hodgkin lymphomas treated with

bendamustine-containing regi-mens. Open Med (Wars). 2021 Apr

21;16(1):672-682.

- Cona A, Tesoro D,

Chiamenti M, Merlini E, Ferrari D, Marti A, Codecà C, Ancona G, Tincati

C, d'Arminio Monforte A, Marchetti G. Disseminated cytomegalovirus

disease after bendamustine: a case report and analysis of circulating

B- and T-cell subsets. BMC Infect Dis. 2019 Oct 22;19(1):881

- García

Muñoz R, Izquierdo-Gil A, Muñoz A, Roldan-Galiacho V, Rabasa P, Panizo

C. Lymphocyte recovery is impaired in patients with chronic lymphocytic

leukemia and indolent non-Hodgkin lymphomas treated with bendamustine

plus rituximab. Ann Hematol. 2014 Nov;93(11):1879-87

- Gafter-Gvili

A, Ribakovsky E, Mizrahi N, Avigdor A, Aviv A, Vidal L, Ram R, Perry C,

Avivi I, Kedmi M, Nagler A, Raanani P, Gurion R. Infections associated

with bendamustine containing regimens in hematological patients: a

retrospective multi-center study. Leuk Lymphoma. 2016;57(1):63-9. https://doi.org/10.3109/10428194.2015.1046862

[TOP]