F.V. Segala1,2, G. Micheli2, C. Seguiti1,2, A. Pierantozzi3, R. Lukwiya4, B. Odong6, F. Aloi5, E. Ochola7, R. Cauda1,2, K. De Gaetano Donati1,2, and A. Cingolani1,2.

1Fondazione Policlinico A. Gemelli, IRCCS, Infectious Diseases, 00168, Roma, Italy.

2 Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, Infectious Diseases Unit, 00168, Roma, Italy.

3 AIFA-Italian Medicine Agency, 00187, Roma, Italy.

4 Comboni Samaritans of Gulu Health Center, 701102, Gulu, Uganda.

5 Università Cattolica S. Cuore, Special Medical Pathology, 00168, Roma, Italy.

6 Medical Teams International, Kitgum, Uganda.

7 Lacor Hospital, Department of HIV, Epidemiology and Documentation, Gulu, Uganda.

Correspondence to:

Francesco Vladimiro Segala, MD, Division of Infectious Diseases,

Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, 00168, Rome, Italy, +39

0630159480. E-mail:

fvsegala@gmail.com

Published: September 1, 2021

Received: May 27, 2021

Accepted: August 8, 2021

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2021, 13(1): e2021055 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2021.055

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Background and Objectives:

HIV infection among vulnerable women (VW) has been attributed to

unfavourable power relations and limited access to sexual and

reproductive health information and services. This work aims to report

sexually-transmitted infections (STI) prevalence and assess the impact

of HIV awareness, demographic and socio-behavioural factors on HIV

status in a rural area of northern Uganda.

Methods:

Pe Atye Kena is a longitudinal cohort intervention study enrolling

young women aged 18-49 years old living in the municipality of Gulu,

Uganda. HIV, HBV, syphilis serologic tests, and a comprehensive

electronic questionnaire on sexual high-risk behaviours were

administered before intervention. In this work, we report baseline

characteristics of the population along with factors associated with

HIV status. Statistical analysis was performed by uni- and

multivariable regression models.

Results:

461 VW were enrolled (mean age: 29 (SD7.7)). 40 (8.7%) were found to be

positive for HIV, 42 (9.1%) for syphilis and 29 (6.3%) for HBV. Older

age (> 34 years vs. < 24 years; OR 4.95, 95% CI: 1.7 to 14);

having done the last HIV test > 12m before the interview (OR 5.21,

95% CI: 2.3 to 11); suspecting the male sexual partner to be HIV+ (OR

2.2; 95% CI: 1.1 to 4.3); not having used condom at first sexual

intercourse (OR 2.6; 95% CI 1.3 to 5.15) were all factors associated

with an incident HIV diagnosis.

Conclusions:

In this cohort, HIV prevalence is high, and sexual high-risk behaviours

are multifaced; future interventions will be aimed to reduce HIV/STIs

misconceptions and to promote a sense of community, self-determination

and female empowerment.

|

Introduction

Despite

substantial reduction in sub-Saharan Africa HIV incidence, young women

remain at the epicentre of the epidemic, representing one of the

populations with the highest number of new cases per year globally.[1,2]

According to the 2020 UNAIDS report, adolescent girls and women account

for 25% of new infections in Western and Southern Africa.[3]

In fact, girls between 14-24 years old are four times more likely to be

infected with HIV than their male peers, and HIV prevalence among women

below 35 years old in Uganda is 7.5% versus 4.3% among males of the

same age.[4] In addition, gender-based violence and inequalities are key drivers of the epidemic.[5]

On the one hand, population-level evidence produced in other African settings[6,7]

show that up to 35% of women below 25 years old are involved in

age-disparate sex (defined as being at least five years younger than

their male partners), identifying this phenomenon as a key risk factor

for an earlier acquisition of HIV.[2,8,9]

On the other hand, several studies have shown that an older male

partner is not only more likely to be HIV positive and have

unsuppressed viral loads,[10] but also that

age-disparate partnerships are frequently associated with other high

risk sexual behaviours (HRSB), such as alcohol consumption,

inconsistent condom use, concurrent sexual partnering and engaging in

transactional sex.[11-15] Furthermore, 10.8% of females reported having sex before the age of 15.

In

addition, existing evidence suggests that socio-economic factors may

exacerbate the risk. For example, being out of school has been

identified as a significant risk factor for HIV acquisition in

Sub-Saharan Africa[16,17] and, in Uganda, women are

consistently more at risk to report a lower level of education or

no-education at all (10.9% versus 3.8%) compared with their male peers.[4]

In addition, according to the 2017 Uganda population-based HIV impact

assessment, recent intimate partner violence (IPV) was reported by

15.5% of women under the age of 24, and exposure to IPV has been linked

both to increased risk of HIV acquisition and reduced ability to

negotiate forms of safe sex.[18] Altogether, these

factors contribute to reducing women's personal agency and their

ability to define and act upon their healthcare choices.[19]

At present, although female empowerment is recognized as a powerful

tool in increasing HIV prevention, only limited evidence is available

on the impact of community interventions on STI incidence and sexual

wellbeing.[20] The present study aims to describe the

state of HIV awareness, risky sexual behaviours, STI epidemiology and

assess the impact of these factors on HIV status in a population of

young women living in a rural area near Gulu, Northern Uganda.

Methods

Study Design and Objectives.

Pe Atye Kena is a longitudinal cohort intervention study enrolling

vulnerable young women (VW) aged 18-49 years old living in a rural area

in the municipality of Gulu, Uganda. However, in this work, we assess

sexually transmitted infections (STI) epidemiology and the impact of

HIV awareness, demographic and socio-behavioural factors on HIV

prevalence before the intended intervention occurs. Therefore, since it

reports data at one precise point in time, the present article is

designed to be a cross-sectional study.

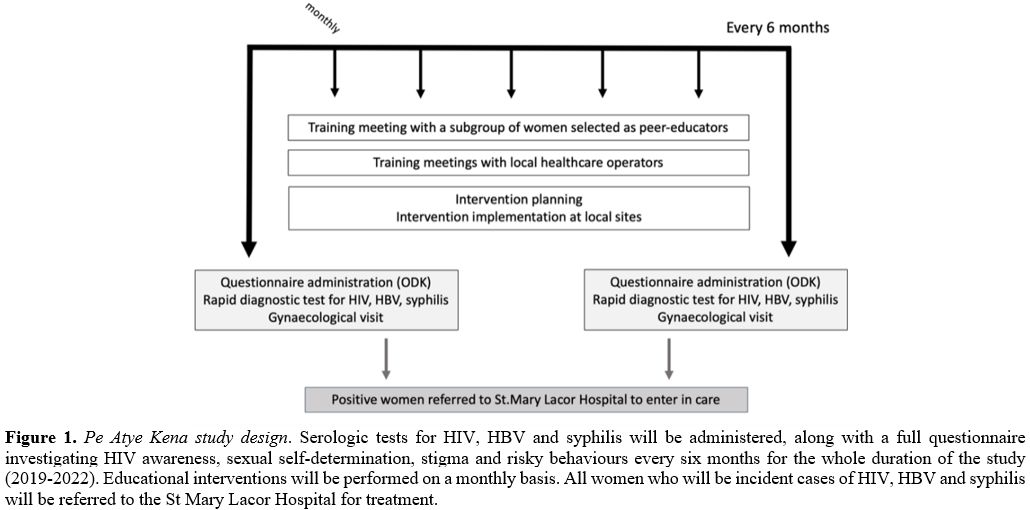

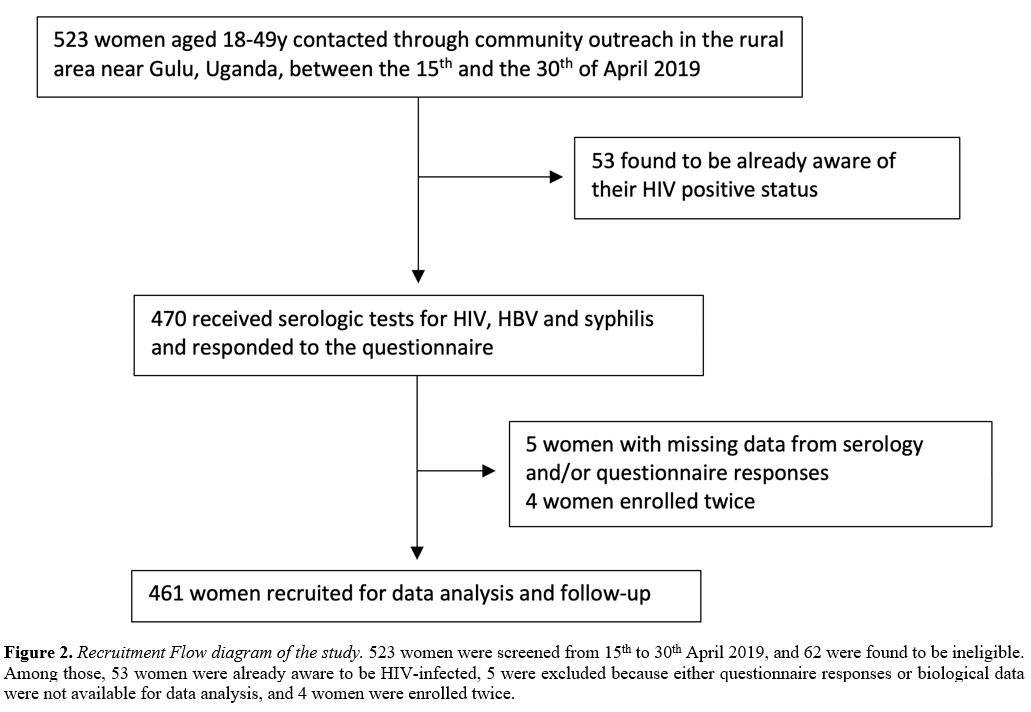

The cohort follow-up has a planned duration of 3 years, from 2019 to 2022 (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1. Pe Atye Kena study design.

Serologic tests for HIV, HBV and syphilis will be administered, along

with a full questionnaire investigating HIV awareness, sexual

self-determination, stigma and risky behaviours every six months for

the whole duration of the study (2019-2022). Educational interventions

will be performed on a monthly basis. All women who will be incident

cases of HIV, HBV and syphilis will be referred to the St Mary Lacor

Hospital for treatment. |

We

expect to identify population-specific critical issues to develop a

permanent, community-based educational service aimed to encourage

sexual self-determination, female personal agency, and improve HIV

prevention. A full electronic questionnaire about HIV awareness and

sexual high-risk behaviours, clinical visits, and laboratory tests

(which included screening for HIV, syphilis, and HBV infection) was

administered before intervention and will be administered every six

months. Behavioural/educational interventions will be delivered monthly

by selected peer-women and CSHC health personnel. Planned interventions

are structured as educational meetings, focus groups,

sharing-experiences groups, and special events involving other

community members (e.g., male partners, friends, family members).

Results from the baseline evaluation were disseminated to the recruited

population during the questionnaire administration and the following

educational meetings.

Recruitment and Cohort Description. Recruitment was conducted by selected peer women through community outreach[21] from the 15th to 30th

April, 2019. A total of eight peer outreach workers were actively

involved in the recruitment phase, who were then selected as peer

educators as well. Enrolled participants were then encouraged to

recruit other women from their community.

Women were eligible if

they were aged between 18 and 49 years old, were living in the area

referring to the Comboni Samaritans Health Center (CSHC) and consented

to data and specimen collection. Women susceptible to contract HIV

infection were defined as "vulnerable" and, therefore, exclusion

criteria included knowing to be positive for HIV at the time of the

interview or participation in other HIV intervention studies. However,

to reinforce the sense of community and prevent stigmatization, women

who were already aware of their HIV status were kept in the follow-up

surveys and into the intervention plan, but they were excluded from the

analysis.

All participants provided written informed consent in

accordance with the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration. The

study was approved by the Lacor Hospital Institutional Research and

Ethics Committee.

Data Collection.

At study entry, participants received a medical history and full

physical examination. The questionnaire was collected through Open Data

Kit Collect (ODK Collect software), hosted on portable Android devices.

Structured interviews were performed by peer educators and CSHC

personnel. The questionnaire was built upon the Uganda AIDS Indicator

Survey variables,[4] and it included a total of 115

questions investigating socio-demographical aspects (23 questions),

sexual activity and life (34 questions), HIV awareness (41 questions),

stigma (10 questions) and sexual self-determination (7 questions). Age

disparate sex was defined when the male partner was five years older or

more.[22]

HIV status was determined through the

4th Generation Alere HIV1/2 rapid Test. In addition, HBV infection was

screened by detection of Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), an

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), while syphilis was screened

using VDRL rapid test-kit. Results were communicated by trained local

health personnel the same day the ODK questionnaire was administered.

During this phase, health operators provided post-test counselling to

all participants. Women who resulted positive for HIV, HBV or Syphilis

were then referred to St. Mary's Lacor Hospital for treatment and

follow-up. Results of serologic tests and responses to the

questionnaire were used as variables for the statistical analysis.

Statistical Analysis.

An initial descriptive analysis was applied to the studied population

for the major variables. Absolute numbers and percentages are shown in

the total sample and subgroups: no known STI; HIV positive; STI

positive. The same indicators have been calculated to evaluate the

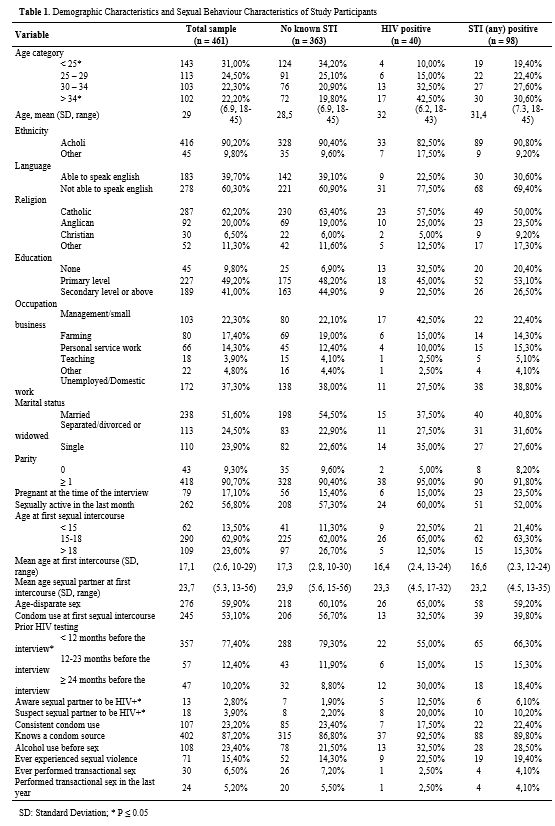

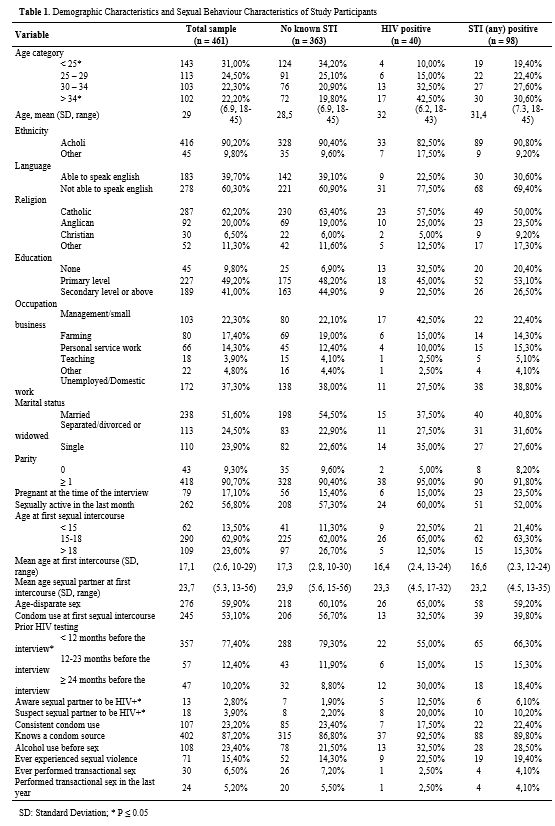

prevalence of HIV, HBV, and syphilis, as well as co-infections (Table 1).

Using

the HIV status to split the population into two groups, positive and

negative, we applied the Chi-Square test to evaluate the difference of

all the major variables of Table 1. Continuous variables were handled as discrete using the categories reported in Table 1.

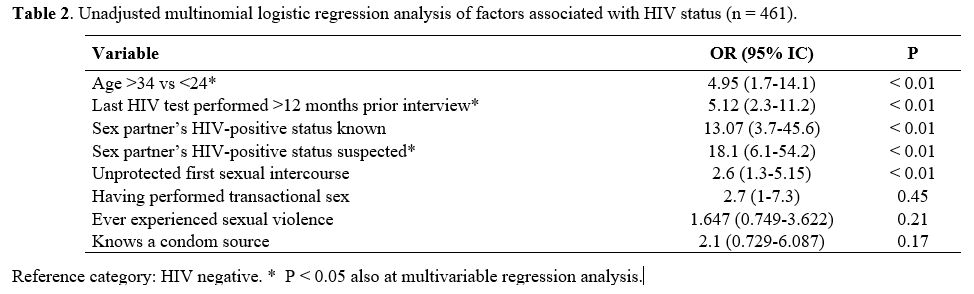

When we found a statistical difference, logistic regressions were

performed to assess the contribution of each variable in predicting HIV

status in terms of the odds ratio. The crude odds ratio and p-value are

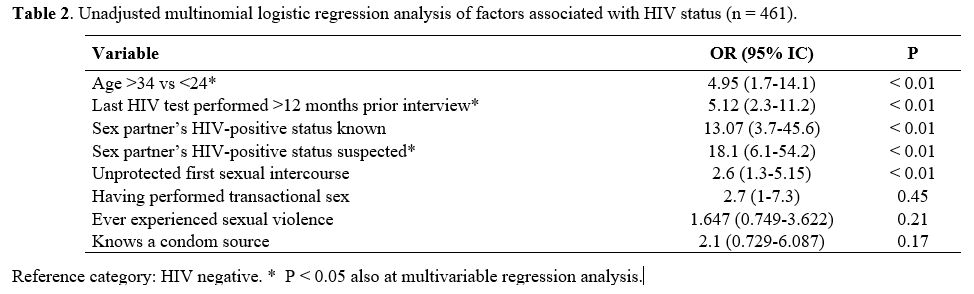

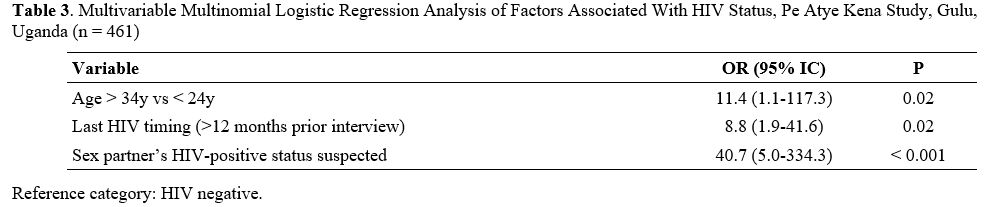

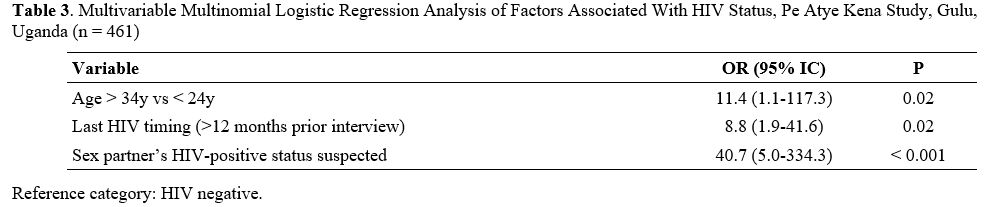

shown in Table 2. The significant variables of table 2 have been tested in a Multivariable Multinomial Logistic Regression, forward method (Table 3). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

All the analyses were carried out using the SAS (v 9.4) software.

|

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics and Sexual Behaviour Characteristics of Study Participants |

|

Table 2. Unadjusted multinomial logistic regression analysis of factors associated with HIV status (n = 461). |

|

Table 3. Unadjusted multinomial logistic regression analysis of factors associated with HIV status (n = 461). |

Results

Study Participants.

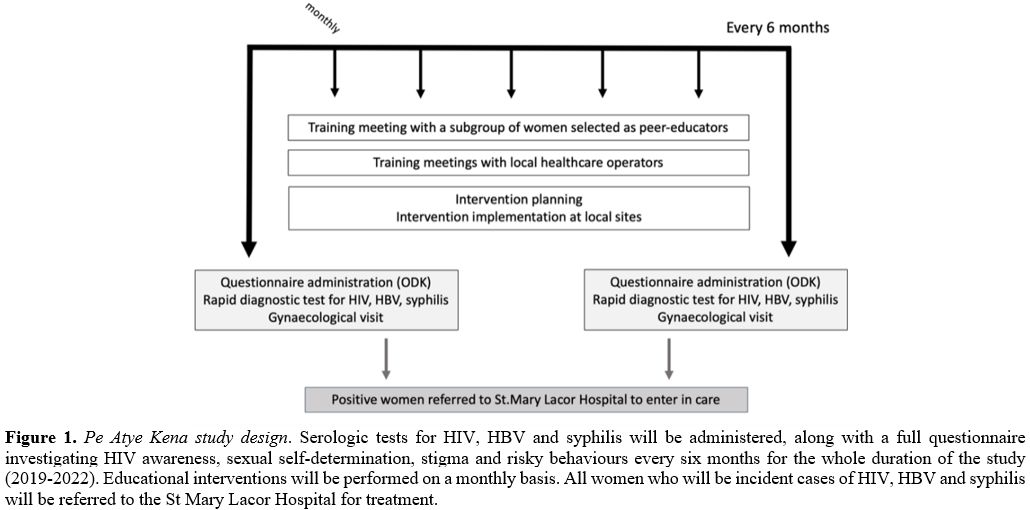

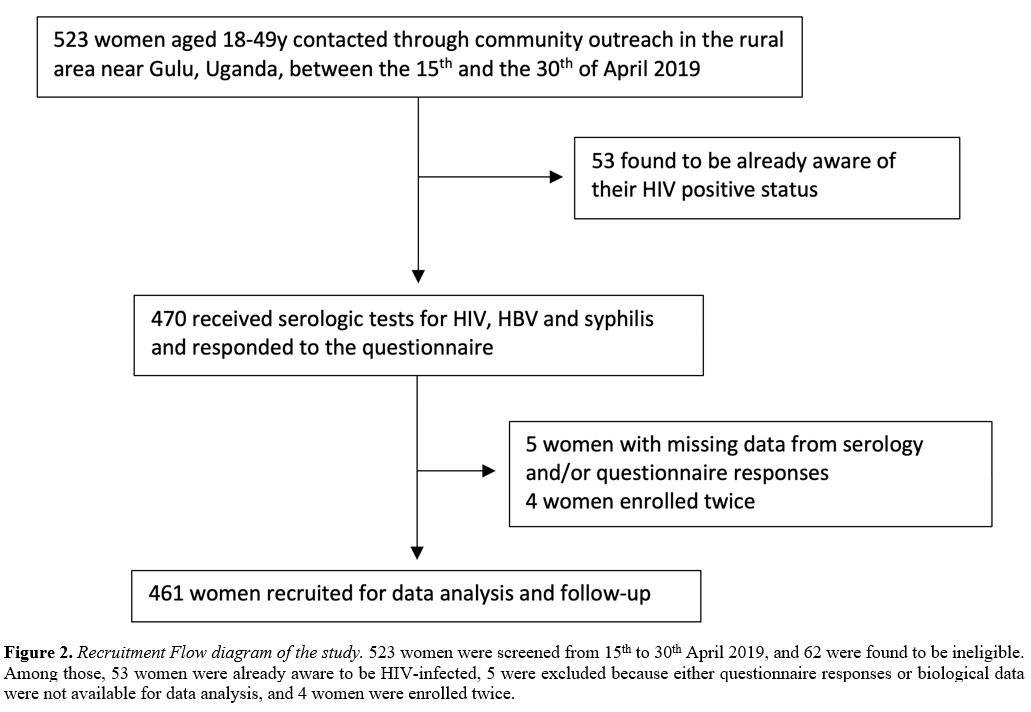

Over the recruitment period (April 15-30, 2019), 523 women were

screened, and 62 were ineligible. Among those, 53 women were already

aware of being HIV-infected, and five were excluded because either

questionnaire responses or biological data were not available for data

analysis. Four women were enrolled twice. Thus, 461 young women were

included in the analysis (Figure 2).

|

Figure 2. Recruitment Flow

diagram of the study. 523 women were screened from 15th to 30th April

2019, and 62 were found to be ineligible. Among those, 53 women were

already aware to be HIV-infected, 5 were excluded because either

questionnaire responses or biological data were not available for data

analysis, and 4 women were enrolled twice. |

Overall,

the median age (interquartile range; IQR) was 28 years (23 - 34). Two

hundred twenty-seven VW (49.2%) attended only primary school, and 183

(39.7%) were able to understand English, and 37.3% (n = 172) declared

to be unemployed at the moment of the interview. Most women (90.7%; n =

418) had given birth at some point in their lifetime, with 79 VW

(17.1%) reporting to be pregnant when the questionnaire was

administered. Demographic Characteristics of study participants are

shown in Table 1.

Out of

461 enrolled women, 40 (8.7%) were found to be HIV positive. Women who

tested positive for syphilis and HBV were, respectively, 42 (9.1%) and

29 (6.3%). Eight HIV-infected women (20%) were also found to be

infected with syphilis, and two women resulted positive to HIV, HBV,

and VDRL serologic tests.

Sexual Activity and Life.

Three-hundred fifty-two women (76.4%;) reported having had their first

sex by the age of 18, 29.1% (n = 136) by the age of 15 and, at their

first sexual intercourse, 53.1% (n = 245) of all women reported not

having used condom. One-hundred sixty-one (34.9%) women reported having

never been tested for HIV. Also, for 276 women (59.9%), their first

male partner was at least five years older than them (i.e.,

age-disparate sex), with a median age difference of 6 years (IQR: 3-9).

Among women who were sexually active in the previous 12 months (87%; n

= 401), only 26.7% (n = 107) consistently used condoms, while 26.9% (n

= 108) reported having consumed alcohol before or after sex at least

once. In addition, 59 women (12.8%) didn't know any place where they

could find condoms, and 15.4% (n = 71) of all women reported having

experienced sexual assault.

13 VW (2.8%) were aware that their

sex partner was HIV-infected, while 18 women (3.8%) suspected their

partner of being HIV+. In addition, up to 5% (n = 24) of recruited

women reported to have performed transactional sex at least once in the

last 12 months, and 6.4% (n = 30) at least once in their lifetime.

Factors Associated with HIV Status.

Older age (> 34 years vs < 24 years; OR 4.95, 95% CI: 1.7 to 14,

p < 0.01), having done the last HIV test more than 12 months before

the interview (OR 5.21, 95% CI: 2.3 to 11, p < 0.01), knowing (OR

13.7; 95% CI: 3.7 to 45, p < 0.01) or suspecting (OR 18.1; 95% CI:

6.1 to 54, p < 0.01) their respective male sex partner to be HIV

positive, not having used condom at the first sexual intercourse (OR

2.6; 95% CI 1.3 to 5.15, p < 0.01), and having performed

transactional sex at least once (OR 2.7; 95% CI: 1 to 7.2, p = 0.45)

were all associated with HIV status in unadjusted multinomial logistic

regression analysis (Table 2).

The multivariable regression model (Table 3)

confirmed a statistically significant effect of older age (> 34

years vs < 24 years; OR 11.4; 95% CI: 1.1 to 117.4, p = 0.02),

infrequent serologic testing (OR 8.8; 95% CI 1.9 to 41.6, p = 0.02),

and of suspecting one’s sexual partner to be HIV+ (OR 40.7; 95% CI 5 to

334.3, p < 0.001).

Discussion

To

our knowledge, with its 461 recruited women, Pe Atye Kena study

represents one of the largest perspective monocentric cohorts

investigating the impact of an intervention in HIV prevention among

women living in rural areas of Sub-Saharan Africa. Our study found

that, in a post-conflict rural area in Northern Uganda, women presented

a high prevalence of HIV, HBV, syphilis and infrequent HIV testing,

older age, and lack of trust in one partner HIV status are all

predictors of being infected with HIV.

With the persistent high

HIV prevalence described in this population, there is an urgent need to

detect community-specific risk factors for HIV acquisition and, more

importantly, to identify strategies effective in averting this

epidemiological trend.[23,24] Therefore, the

development of population-specific interventions aimed to reduce STI

vulnerability among girls and young women is included in 2017/2018

National HIV and AIDS Action Plan.[25]

Our population showed an HIV prevalence similar to the one reported by the 2018 Uganda Population-based HIV Assessment.[4] Also, consonant with other studies in Sub-Saharan Africa,[10]

an important portion of women reported age-disparate sex, few years of

schooling, inconsistent condom use, early sexual debut, and experience

of sexual-related violence.[8,26-28] HIV testing and old age are well-recognized factors associated with HIV-positive status.

Similar

to UPHIA assessment was also the rate of self-reported HIV-status

awareness, defined as having done the last HIV test within 12 months

before the interview. During the screening procedures, 53 women did not

meet the inclusion criteria because they already knew to be

HIV-infected, for HIV, and they were almost entirely already taking ARV

(52/53). Hence, among a total of 93 HIV-positive women who participated

in Pe Atye Kena screening activities, 43% was unaware of their HIV

status, which is almost twice the rate expected for women living in the

region.[4] Since our study targeted women at risk for

contracting STIs, this data is likely altered by a selection bias.

However, lack of HIV-status awareness represents a critical challenge

to achieve UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets.[3] Thus, our study may highlight the need to increase outreach and screening efforts among women living in the Gulu region.

In

our view, it is important to emphasize that the data presented here

refer to a population that is largely underrepresented in other large,

sub-Saharan cohort studies: to our knowledge, the DREAMS partnership is

the only study targeting, to some extent, a population of women living

in rural areas, where AIDS/HIV education and epidemiological data are

most needed.[29] Furthermore, unlike other large

cohort studies targeting similar populations, the present study is

entirely conducted by a second-level health center (village-based

health centre with a target population of 5000 people).[30] Thus, it may be used as a model for further community-based interventions.

Among

women enrolled in Pe Atye Kena study, both the prevalence of ever

having had syphilis and prevalence of current HBV infection (acute or

chronic, defined as being positive to hepatitis B surface antigen

assay) was higher than the one described for women living in the same

region by 2018 UPHIA report but lower than the one reported in other

studies.[31,32] In our study, 5% (2/40) of

HIV-infected women were co-infected with HBV, and 20% (8/40) of

HIV-infected women screened positive for syphilis. Interestingly, the

two women who resulted positive both to HBV and HIV also had syphilis.

Our study did not intend to assess the overall prevalence of sexually

transmitted diseases in the population. Therefore, the results are not

generalizable to all Gulu female population, but, noteworthy, the

burden of co-infections between HIV and other STIs in Sub-saharan

Africa remain controversial.[33,34]

Our study

has several limitations. First, as mentioned above, the reported

prevalence of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases is not

generalizable to the overall population due to both outreach targets

and small sample size. Second, we did not include girls below 18 years

old, knowing that the risk of HIV acquisition substantially increases

from the age of 15.[13] Third, although standardized

and administered by trained healthcare personnel, interviews were

performed face-to-face, and some interviewer bias, response bias, or

misreporting of sexual behaviors is possible. Finally, longitudinal

follow-up is expected to clarify risk behaviours and retention in the

study and assess the efficacy of a peer-conducted educational

intervention in sexual behaviours and HIV/STIs acquisition.

Conclusions

Among

the 461 women included in this analysis, the prevalence of HIV and

other STIs was high, and the proportion of women who were unaware of

their serological status was much higher than the one expected for the

region. Also, despite substantial efforts in promoting HIV and sexual

prevention, high-risk sexual behaviours were a persistent challenge,

also considering that experiences of sexual assault, intimate partner

violence, and transactional sex were, most likely, consistently

underreported. In response to these findings, we plan to implement

targeted interventions to reduce HIV/STIs misconceptions and promote a

sense of community, self-determination, and female empowerment. If we

would be able to engage and retain women in our project successfully,

we expect to reduce the incidence of risky behaviours through the

construction of a stable, community-based educational subsidy. Women

play an essential role in the socio-economic development of sub-Saharan

Africa and, as we proceed to analyse whether our intervention is going

to impact sexual health among our population, we recognize the need for

future research to focus on the importance of insufficient female

personal agency and unequal power relations in the fight for HIV and

STI prevention.

Acknowledgements

The

authors thank the women of Pe Atye Kena study. Special recognition is

due to the "peer educators" whose contribution was essential in

recruiting and retention in study. Pe Atye Kena peer educators are:

Ajok Gloria, Lamara Barbara, Akello Kevine, Aineligio Irene, Akello

Hellen, Aol Nighty, Akello Susan and Lamunu Grace.

Ethics Committee and Consent

The

present study was approved by St Mary's Hospital Lacor Ethics Committee

(LHIREC, contact n° 0772561783), by written consent (n° 096/05/19). All

participants provided written informed consent for data and specimen

collection.

References

- Dellar RC, Dlamini S, Karim QA. Adolescent girls

and young women: key populations for HIV epidemic control. J Int AIDS

Soc. 2015;18(suppl 1):19408. https://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.18.2.19408

- Shisana

O, Rehle T, Simbayi L, et al. South African National HIV Prevalence,

Incidence and Behaviour Survey, 2012. Cape Town, South Africa: Human

Sciences Research Council Press; 2014. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11910/2490

- UNAIDS. 2020 Global AIDS update. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2020/global-aids-report [accessed 2020 Nov 17].

- Ministry

of Health, Uganda. Uganda Population-based HIV Impact Assessment

(UPHIA) 2016-2017: Final Report. Kampala: Ministry of Health; July,

2019. https://phia.icap.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/UPHIA_Final_Report_Revise_07.11.2019_Final_for-web.pdf

- Robinson

JL, Narasimhan M, Amin A, et al. Interventions to address unequal

gender and power relations and improve self-efficacy and empowerment

for sexual and reproductive health decision-making for women living

with HIV: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2017 Aug 24;12(8):e0180699. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180699

- Mabaso

M, Sokhela Z, Mohlabane N, et al. Determinants of HIV infection among

adolescent girls and young women aged 15-24 years in South Africa: a

2012 population- based national household survey. BMC Public Health.

2018;18(1):183. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5051-3

- Evans

M, Risher K, Zungu N, et al. Age-disparate sex and HIV risk for young

women from 2002 to 2012 in South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc.

2016;19(1):21310. https://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.19.1.21310

- Topazian

HM, Stoner MCD, Edwards JK, Kahn K, et al. Variations in HIV risk by

young women's age and partner age-disparity in rural South Africa (HPTN

068). JAIDS. 2020; 83(4):350-356. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000002270

- Maughan-Brown

B, Kenyon C, Lurie MN. Partner age differences and concurrency in South

Africa: Implications for HIV-infection risk among young women. AIDS

Behav. 2014;18(12):2469-2476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0828-6

- Maughan-Brown

B, George G, Beckett S, Evans M, et al. HIV Risk Among Adolescent Girls

and Young Women in Age-Disparate Partnerships: Evidence From

KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. JAIDS. 2018; 78(2):155-162 HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.1097/QAI.0000000000001656

- Santelli

JS, Edelstein ZR, Mathur S, Wei Y, Zhang W, Orr MG, et al. Behavioral,

biological, and demo- graphic risk and protective factors for new HIV

infections among youth in Rakai, Uganda. JAIDS. 2013; 63(3):393–400. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182926795

- Balkus

JE, Brown E, Palanee T, Nair G, Gafoor Z, Zhang J, et al. An Empiric

HIV Risk Scoring Tool to Predict HIV-1 Acquisition in African Women.

JAIDS. 2016; 72(3):333–43. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000000974

- Saul

J, Bachman G, Allen S, Toiv NF, Cooney C, Beamon T. The DREAMS core

package of interventions: A comprehensive approach to preventing HIV

among adolescent girls and young women. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(12):

e0208167. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208167

- Gaffoor

Z, Wand H, Daniels B, Ramjee G. High risk sexual behaviors are

associated with sexual violence among a cohort of women in Durban,

South Africa. BMC Research Notes. 2013, 6:532 https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-6-532

- Maughan-Brown

B, Evans M, George G. Sexual behaviour of men and women within

age-disparate partnerships in South Africa: implications for young

Women's HIV risk. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0159162. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159162

- De

Neve JW, Fink G, Subramanian SV, Moyo S, Bor J. Length of secondary

schooling and risk of HIV infection in Botswana: evidence from a

natural experiment. Lancet Glob Health. 2015; 3(8):e470–e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00087-X

- Behrman

JA. The effect of increased primary schooling on adult women's HIV

status in Malawi and Uganda: Universal Primary Education as a natural

experiment. Soc Sci Med. 2015; 127:108–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.06.034

- Maman

S, Campbell J, Sweat MD, Gielen AC. The intersections of HIV and

violence: Directions for future research and interventions. Soc Sci

Med. 2000 Feb;50(4):459-78.

- Donald A, Koolwal G, Annan J, Falb K, Goldstein M. Measuring Women's Agency. World Bank Group. 2017. https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/10.1596/1813-9450-8148

- UNAIDS. Empowering women is critical to ending the AIDS epidemic. UNAIDS Press Statement. Available at: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/pressreleaseandstatementarchive/2015/march/20150308_IWD

- Dancy NC, Dutcher GA. HIV/AIDS information outreach: a community-based approach. J Med Libr Assoc. 2007;95(3):323-329. https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.95.3.323

- UNAIDS. UNAIDS Terminology Guidelines. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2015. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2015_terminology_guidelines_en.pdf

- Pettifor

A, Bekker LG, Hosek S, DiClemente R, Rosenberg M, Bull SS, et al.

Preventing HIV among young people: research priorities for the future.

JAIDS. 2013; 63 Suppl 2:S155– 60. https://doi.org/10.1097/qai.0b013e31829871fb

- UNAIDS.

HIV prevention among adolescent girls and young women: Putting HIV

prevention among adolescent girls and young women on the Fast-Track and

engaging men and boys. UNAIDS Guidance. 2016. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_HIV_prevention_among_adolescent_girls_and_young_women.pdf

- UAC

(2015) National HIV and AIDS Strategic Plan 2015/2016- 2019/2020, An

AIDS free Uganda, My responsibility! Uganda AIDS Commission

Secretariat. https://uac.go.ug/sites/default/files/National%20HIV%20and%20AIDS%20Strategic%20Plan%202015-2020.pdf

- Pettifor

AE, Rees HV, Kleinschmidt I, Steffenson AE, MacPhail C, Hlongwa-

Madikizela L, et al. Young people's sexual health in South Africa: HIV

prevalence and sexual behaviors from a nationally representative

household survey. AIDS. 2005;19:1525-34. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aids.0000183129.16830.06

- Hallman

K. Gendered socio-economic conditions and HIV risk behaviours among

young people in South Africa. Afr J AIDS Res. 2005;4:37-50. https://doi.org/10.2989/16085900509490340

- Joint

United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), Interagency Task Team on

HIV and Young People. Guidance brief: HIV interventions for most

at-risk young people. New York: UNFPA; 2008. https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/mostatrisk.pdf

- Birdthistle

I, Schaffnit SB, Kwaro D, Shahmanesh M, Ziraba A, et al. Evaluating the

impact of the DREAMS partnership to reduce HIV incidence among

adolescent girls and young women in four settings: a study protocol BMC

Public Health. 2018; 18:912. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5789-7

- Ministry

of Health, The Republic of Uganda. Guidelines for Designation,

Establishment and Upgrading of Health Units. The Health lnfrastructure

Working Group, 2011. Available at: https://health.go.ug/docs/guidelines.pdf

- Ocama

P, Seremba E, Apica B, Opio K. Hepatitis B and HIV co-infection is

still treated using lamivudine-only antiretroviral therapy combination

in Uganda. African Health Sciences. 2015; (15) 2: 328-333. https://doi.org/10.4314/ahs.v15i2.4

- Sun

HY, Sheng WH, Tsai MS, Lee KY, Chang SY, Hung CC. Hepatitis B virus

co-infection in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients: A

review. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:14598-614 https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i40.14598

- Barth

RE, Huijgen Q, Taljaard J, Hoepelman AIM. Hepatitis B/C and HIV in

sub-Saharan Africa: an association between highly prevalent infectious

diseases. A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal

of Infectious Diseases. 2010. 14(12):e1024-e1031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2010.06.013

- Chiesa

A, Ochola E, Oreni L, Vassalini P, Rizzardini G, Galli M. Hepatitis B

and HIV co-infection in Northern Uganda: Is a decline in HBV prevalence

on the horizon? PLoS ONE 2020. 15(11): e0242278. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0242278

[TOP]