Pouyan Kheirkhah1, Ana M. Avila-Rodriguez2, Bartlomiej Radzik1 and Carlos Murga-Zamalloa1.

1 Department of Pathology, University of Illinois at Chicago, USA.

2 Department of Internal Medicine, University of Illinois at Chicago, USA.

Correspondence to: Carlos

A. Murga-Zamalloa, M.D. Department of Pathology, University of Illinois

at Chicago, 840 S Wood Street, 260 CMET, Chicago, IL 60607. Tel:

312-413-3998. E-mail:

catto@uic.edu

Published: November 1, 2021

Received: September 7, 2021

Accepted: October 19, 2021

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2021, 13(1): e2021067 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2021.067

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Myeloid

sarcomas can be detected in up to 30% of acute myeloid leukemia cases

or occur de-novo without bone marrow involvement. The most frequent

localization of myeloid sarcomas in the abdominal cavity is the small

intestine, and gastric presentations are infrequent, frequently

misdiagnosed, and a high level of suspicion should exist when the

characteristic histomorphology features are present. The current review

features a case report with gastric presentation of myeloid sarcoma in

a patient with a diagnosis of acute myeloid leukemia with trisomy 8. In

addition, a review of the literature of intestinal-type myeloid

sarcomas shows that less than 15% of these cases have been reported in

the stomach. The most common molecular aberrancy detected in intestinal

myeloid sarcomas is the fusion protein CBFB-MYH11. A review of several

large studies demonstrates that the presence of myeloid sarcoma does

not constitute an independent prognostic factor. The therapeutic

approach will be tailored to the specific genetic abnormalities

present, and systemic chemotherapy with hematopoietic stem cell

transplant is the most efficient strategy.

|

Case Presentation

A

60-year-old male with a relevant past medical history of hepatitis C

infection, methadone use, and heroin addiction was surgically managed

for a toe infection. Persistent leukocytosis was noted despite

antibiotic treatment, and a microscopic review of the peripheral blood

smear demonstrated circulating blasts with left shift in granulocytes.

Bone marrow biopsy evaluation demonstrated 70-80% myeloblasts, and the

concurrent flow cytometric analysis show myeloblasts with the

expression of CD34, CD117, CD33, CD11c, CD13, and negative for CD56. A

diagnosis of acute myeloid leukemia was rendered. Karyotype analysis of

the bone marrow aspirate demonstrated trisomy 8 (47, XY, +8[2]/46,

XY[18]). Molecular testing demonstrated mutations in SRF2, TET2, and

KRAS genes (SRSF2 P95H, TET2 F1901Lfs*4, TET2 S585*, KRAS A146T).

During admission, the patient complained of persistent abdominal pain,

with coffee-ground emesis and one episode of melena. Computed

tomography showed thickening of the gastric wall near the

gastroesophageal junction with multiple enlarged lymph nodes. An urgent

esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed a large, firm, ulcerated, and

partially circumferential mass in the cardia extending into the fundus,

with multiple ulcers within the gastric fundus and proximal duodenum.

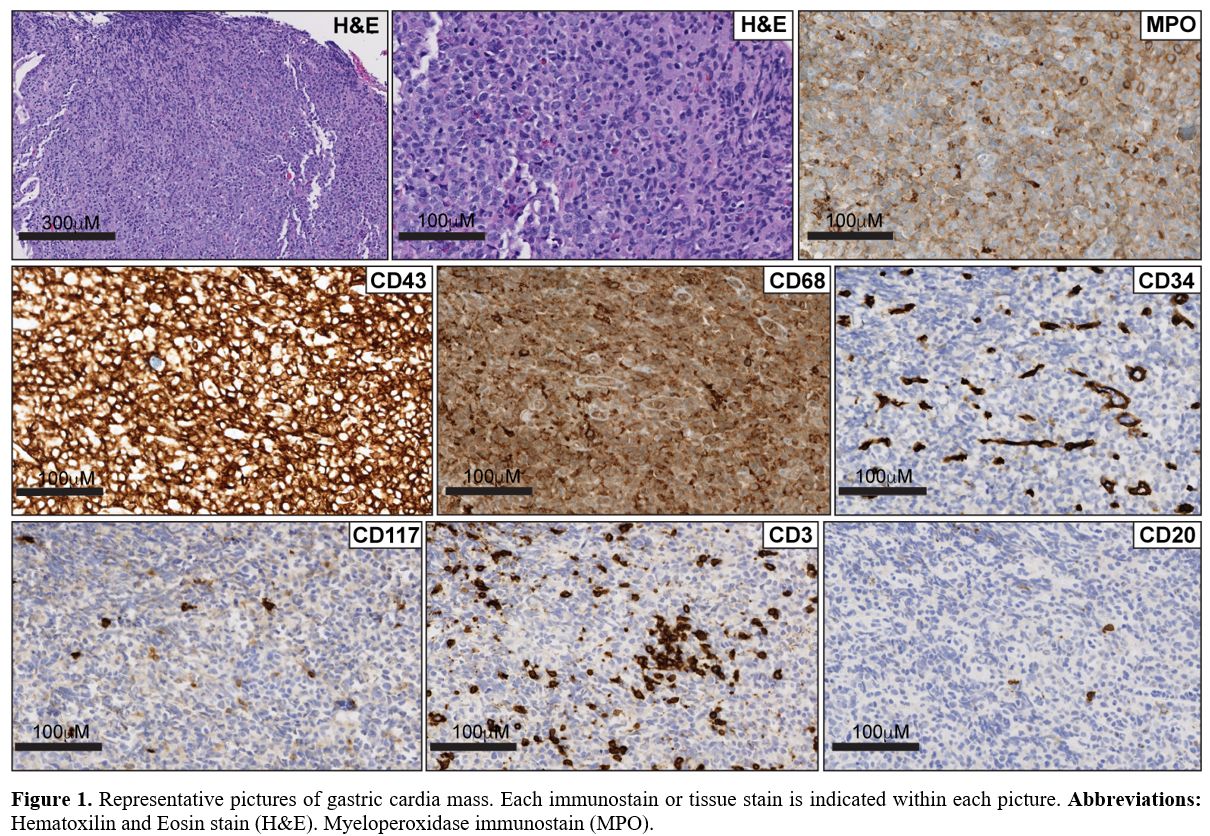

Histologic evaluation from biopsies of the cardia mass demonstrated

dense submucosal aggregates, composed of large cells, with lobated

nuclear contours and fine and dispersed chromatin with inconspicuous

nucleoli (Figure 1).

Immunohistochemical stains demonstrated that the infiltrates were

positive for MPO, CD43, with weak CD68 expression, and negative for

CD34, CD117, CD20, CD79a, CD5, CD3 and cyclin D-1 (Figure 1). A diagnosis of myeloid sarcomas was established. The following questions arise from this case: How

often is myeloid sarcoma identified in the stomach, and what are the

specific histological features that help establish the diagnosis? Do

intestinal myeloid sarcomas share common molecular features? What is

the prognosis and management of myeloid sarcomas?

|

Figure

1. Representative

pictures of gastric cardia mass. Each immunostain or tissue stain is

indicated within each picture. Abbreviations: Hematoxilin and Eosin

stain (H&E). Myeloperoxidase immunostain (MPO). |

Definition and Frequency of Myeloid Sarcoma

Myeloid

sarcoma (MS) is defined by the presence of neoplastic extramedullary

infiltrates of myeloid precursors at a single or multiple sites, and

the term leukemia cutis is reserved for when those infiltrates are

present in the skin.[1] The incidence of myeloid sarcoma is variable, it has been reported in 7% to 30% of the cases of acute myeloid leukemia,[2]

and this variability will largely depend on the criteria utilized to

define extramedullary involvement. The majority of the studies that

identified myeloid sarcoma by physical examination and/or imaging

studies demonstrated a prevalence in the range of 20% to 30%, in

contrast to studies with the only biopsy-proven diagnosis that

identified a prevalence of 7-10%.[1-4]

Position-electron tomography (PET) has also been utilized, with

reported increased sensitivity compared to physical exam or other

imaging techniques.[5,6] A single prospective study

that compared PET-imaging, clinical examination, and histologic

analysis, reported an incidence of 22% with a sensitivity of 77% and

specificity of 97% for FDG-PET.[5]

The more

frequent localizations of myeloid sarcoma will also depend on the

methodology utilized for its detection. Detection by physical

examination identifies, as the most frequent sites, the gingiva,

spleen, and lymph nodes.[2] When imaging or biopsy

studies are utilized during the diagnosis, the most frequently involved

sites include the lymph nodes, testis, bone, and soft tissue.[1,7]

Some studies do not consider gingival, lymph node, liver, or splenic

involvement as myeloid sarcoma, as the hypertrophy identified during

physical examination may constitute migration/extravasation of blast

precursors and not a truly ‘tumor’ lesion.[5,8,9]

Myeloid

sarcoma can occur de-novo without simultaneous bone marrow involvement,

and in these instances, the diagnosis may be challenging, as it can be

misdiagnosed as lymphoma.[10,11] Moreover, a

diagnosis of myeloid sarcoma can precede the occurrence of acute

myeloid leukemia, or the occurrence of myeloid sarcoma can be the sole

manifestation of relapse. No specific risk factors for myeloid sarcoma

are identified; however, surface expression of CD56,[12] and CD11b,[2] and monocytic differentiation[4] are reported to be associated with an increased risk for the presence of extramedullary involvement by leukemia.

Intestinal Myeloid Sarcoma

Involvement

of the gastrointestinal tract by myeloid sarcoma is not a common

occurrence, and the most involved site is the small intestine. A PubMed

search using a combination of the terms’ intestinal’ ‘gastric’ ‘myeloid

sarcoma’ and ‘granulocytic sarcoma’ identified 58 individual clinical

case reports of myeloid sarcoma localized in the intestinal tract. From

the list, only 7 cases were reported to be localized in the gastric

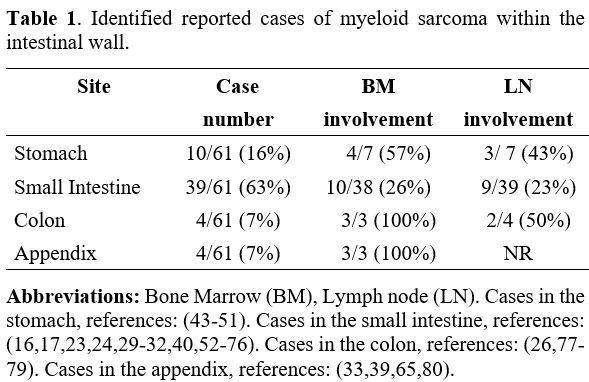

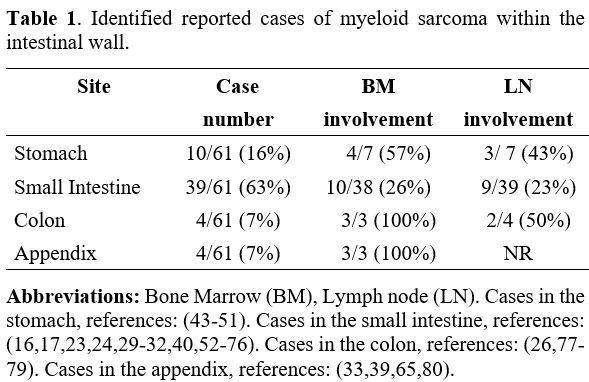

compartment (Table 1). The

clinical presentation for gastric myeloid sarcoma was characterized by

non-specific symptoms, including persistent vague abdominal pain and

vomiting. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy usually revealed thickening

of the stomach mucosa with hyperemic lesions and occasional nodularity

or tumor-forming lesions. Imaging studies, including computer

tomography (CT) scans, often revealed enlarged lymph nodes around the

stomach. In the current literature review series, 60% of the cases (n =

50) did not feature synchronous bone marrow involvement by acute

leukemia, making the diagnosis more challenging. Importantly, five

reported cases featured relapse of acute myeloid leukemia in the form

of gastrointestinal myeloid sarcoma, and three of those cases were post

stem cell transplantation.

|

Table 1. Identified reported cases of myeloid sarcoma within the intestinal wall. |

Histologic Evaluation and Differential Diagnosis of Intestinal Myeloid Sarcomas

Myeloid

sarcomas are histologically characterized by dense submucosal

infiltrates, predominantly composed of large cells with cleaved or

slightly folded nuclear contours, variable amounts of cytoplasm, and

finely dispersed chromatin.[11] However, similar

features can be identified in lymphoid and non-lymphoid neoplasms in

the intestinal tract; so, the differential diagnosis includes mature

lymphoproliferative neoplasms like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, the

blastoid variant of mantle cell lymphoma, and mature T-cell neoplasms

with secondary GI tract involvement or primary to the GI tract.

Non-hematolymphoid neoplasms that may show similar morphological

features includes poorly differentiated carcinoma and melanoma. The

possibility of benign extramedullary hematopoiesis (myeloid metaplasia)

should also be included in the differential diagnosis; however, those

are characterized by multilineage hematopoietic elements at progressive

stages of maturation.

Myeloid sarcoma localized within the

intestinal tract is not a frequent presentation and lacks specific

clinical symptoms; therefore, the diagnosis may remain elusive unless

clinical suspicion and a careful histological analysis exist. A

misdiagnosis of myeloid sarcoma is not uncommon,[11,13] one report indicated that 58% (n = 26) of cases were originally diagnosed as lymphoma,[14] and two independent reports demonstrated that 44% (n = 61) and 46% (n = 158) were initially mislabeled as lymphoma.[11,15]

Therefore, immunohistochemical stains are required to establish a

diagnosis, and a panel that includes myeloid-specific markers (MPO,

CD117), should be included with any suspicious infiltrate. The current

literature review demonstrates that the majority of the cases within

the intestinal tract featured positive expression of either CD34 (91%,

n = 36) or CD117 (93%, n = 29), and only a single report was identified

with negative expression of both of these markers (Table 1).[16] Importantly, expression of either CD43 (94%, n = 17) and MPO (97%, n = 32) is frequently detected in the tumor cells (Table 1).

Aberrant expression of associated lymphoid markers has been reported in

cases of myeloid sarcoma, including CD3 and CD79a. The current review

for the intestinal presentation of myeloid sarcoma shows that CD3 was

positive in a single case,[17] and expression of CD5,

CD20, and CD79a was not detected in any of the cases included. The

current case report also demonstrated divergent CD34 and CD117 between

the bone marrow biopsy and the stomach biopsies, a phenomenon

previously described in leukemia cutis.[18]

Recurrent Cytogenetic Abnormalities in Intestinal Myeloid Sarcomas

The previous series indicated that trisomy 8 is commonly detected in cases of myeloid sarcoma[19] and leukemia cutis,[20]

and the presence of chromosome 8 abnormalities are associated with

worse responses to initial therapies and worse overall clinical

outcomes.[21,22] Unlike the current case, the

literature review did not identify any previous report of abdominal

myeloid sarcoma with trisomy 8. Previous reports demonstrated a higher

prevalence for abdominal localization of myeloid sarcomas that are

positive for the CBFB-MYH11 fusion.[23] The largest

series to date included 13 cases of myeloid sarcoma with an abdominal

presentation, and 11 (85%) of those cases were positive for CBFB-MYH11

fusion protein.[23] The same report included an

additional number of 22 cases that were identified from reported cases

in the literature, and 20 (92%) of those cases were positive for

CBFB-MYH11 fusion protein.[23] The current review of the literature identified 11 additional cases of intestinal myeloid sarcoma[17,24-33]

that evaluated for genetic abnormalities by either cytogenetic or

molecular testing, and the most common chromosomal rearrangement was

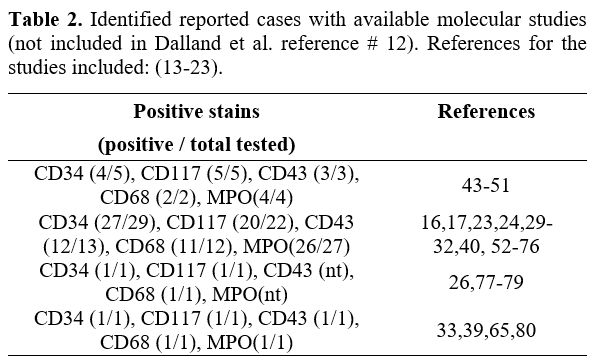

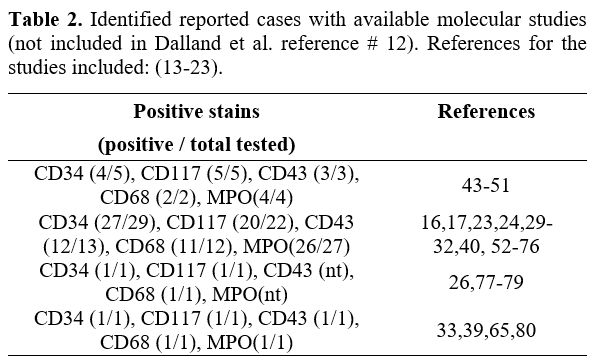

inv(16) in 27% (3/11) of the cases (Table 2).

|

Table 2. Identified reported cases with available molecular studies (not included in Dalland et al. reference # 12). References for the studies included: (13-23).

|

Prognosis of Myeloid Sarcoma

Poor

outcomes with negative trends in the overall survival and event-free

survival sarcoma have been associated with a diagnosis of myeloid

sarcoma.[7,22] However, when

adjusted to age and cytogenetic risk, myeloid sarcoma is not identified

as an independent prognostic factor for overall survival,[2,4,34] and the overall 5-year survival rate for patients with concomitant myeloid sarcoma is no different from those without it.[1]

A retrospective study that evaluated the clinical outcomes of 84

patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients positive for

t(8;21)(AML1/ETO) included eight patients with extramedullary

involvement with significant worst responses to initial induction

chemotherapy. However, half of the patients with extramedullary

involvement featured CNS leukemic infiltration,[21] and additional studies did not identify myeloid sarcoma as an adverse prognostic factor in this subset of cases.[4]

Management of Myeloid Sarcoma

The

treatment of myeloid sarcoma will depend on the form of presentation

and whether this occurs at the initial diagnosis or at relapse.[1]

In the current era of targeted therapies, the consensus is to tailor

the therapeutic approach based on the tumor’s genetic profile, and

therefore molecular and cytogenetic testing are required to formulate

the treatment strategies.[35]

As a rare

condition, the lack of randomized controlled trials limits the

treatment strategies for isolated myeloid sarcoma without bone marrow

involvement. Retrospective series have demonstrated that delayed or

localized therapy alone will almost always progress to AML.[1,35]

Remission-type induction chemotherapy regimens have also been used in

isolated myeloid sarcoma, demonstrating a decrease in the rate of

progression and an increase in overall survival.[35,36]

The role of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) following

induction therapy is supported by retrospective studies, which indicate

that allogeneic HSCT is associated with a 5-year overall survival rate

of 48% and leukemia-free survival of 36%.[37] Localized radiation therapy (RT) has also been considered as consolidation treatment for isolated MS.[38]

Systemic

treatment is the first-line option for myeloid sarcoma with concurrent

marrow involvement at diagnosis. First-line treatments for

gastrointestinal myeloid sarcoma usually include conventional induction

chemotherapy with a combination of cytarabine and anthracycline agents.[39,40]

Unfortunately, there have been no randomized trials comparing the

different types of chemotherapy regimens and assessing the optimal AML

remission-induction chemotherapy regimens in the setting of myeloid

sarcoma with marrow involvement. However, autologous and allogeneic

HSCT are usually considered as treatment intensification based on the

superior outcomes with the use of HSCT in several retrospective

studies.[37,38]

Isolated myeloid sarcoma at

relapse is rare and usually precedes marrow relapse. For relapse after

chemotherapy alone, strategies such as relapse-type chemotherapy

regimens and localized radiation therapy (RT) are recommended.[1]

Isolated myeloid sarcoma after HSCT can present as the first

manifestation of relapse but has rarely been described, and currently,

there is no established standardized management. The therapeutic

strategies include donor lymphocyte infusion, tapering of

immunosuppression, or enrollment in clinical trials.[41]

Concomitant MS and marrow relapse are usually treated with reinduction

chemotherapy taking into account the possibility of HSCT or RT.[38]

In the setting of marrow and myeloid sarcoma relapse after HSCT, the

survival is poor and investigational agents or palliative care measures

must be considered.[1]

Finally, noncontrolled

anecdotal reports have described the use of highly targeted therapies

as a treatment strategy for myeloid sarcoma. For example, the humanized

anti-CD33 monoclonal antibody has been associated with good responses.[35,36]

In addition, tyrosine kinase inhibitors have also shown promising

results in a patient with myeloid sarcoma associated with FIP1L1-

PDGFRA fusion gene and eosinophilia.[42]

Conclusions

Myeloid

sarcoma can occur in up to 30% of newly diagnosed acute myeloid

leukemia. According to the site presentation, it is usually identified

by physical examination and imaging studies, and a confirmatory biopsy

will be required in a proportion of the cases. Histology analysis shows

overlapping morphology with mature lymphoproliferative neoplasms, and

immunohistochemical analysis is required to establish the diagnosis.

The most common site within the intestinal tract is the small

intestine, and the expression of CD34, MPO, and CD117 are the most

sensitive and specific markers. The aberrant fusion protein CBFB-MYH11

is the most predominant cytogenetic abnormality detected in intestinal

myeloid sarcoma. A diagnosis of myeloid sarcoma does not appear to

render a worse prognosis in comparison with patients that do not

feature extramedullary disease. The clinical management of myeloid

sarcoma will largely depend on the timing of the presentation and the

underlying genetic landscape of the tumor.

References

- Bakst RL, Tallman MS, Douer D, Yahalom J. How I treat extramedullary acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2011;118(14):3785-93. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2011-04-347229 PMid:21795742

- Ganzel

C, Manola J, Douer D, Rowe JM, Fernandez HF, Paietta EM, et al.

Extramedullary Disease in Adult Acute Myeloid Leukemia Is Common but

Lacks Independent Significance: Analysis of Patients in ECOG-ACRIN

Cancer Research Group Trials, 1980-2008. J Clin Oncol.

2016;34(29):3544-53. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.67.5892 PMid:27573652 PMCid:PMC5074349

- Avni

B, Rund D, Levin M, Grisariu S, Ben-Yehuda D, Bar-Cohen S, et al.

Clinical implications of acute myeloid leukemia presenting as myeloid

sarcoma. Hematol Oncol. 2012;30(1):34-40. https://doi.org/10.1002/hon.994 PMid:21638303

- Fianchi

L, Quattrone M, Criscuolo M, Bellesi S, Dragonetti G, Maraglino AME, et

al. Extramedullary Involvement in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. A Single

Center Ten Years' Experience. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis.

2021;13(1):e2021030. https://doi.org/10.4084/MJHID.2021.030 PMid:34007418 PMCid:PMC8114885

- Stolzel

F, Luer T, Lock S, Parmentier S, Kuithan F, Kramer M, et al. The

prevalence of extramedullary acute myeloid leukemia detected by

(18)FDG-PET/CT: final results from the prospective PETAML trial.

Haematologica. 2020;105(6):1552-8. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2019.223032 PMid:31467130 PMCid:PMC7271590

- Cribe

AS, Steenhof M, Marcher CW, Petersen H, Frederiksen H, Friis LS.

Extramedullary disease in patients with acute myeloid leukemia assessed

by 18F-FDG PET. Eur J Haematol. 2013;90(4):273-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejh.12085 PMid:23470093

- Paydas

S, Zorludemir S, Ergin M. Granulocytic sarcoma: 32 cases and review of

the literature. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47(12):2527-41. https://doi.org/10.1080/10428190600967196 PMid:17169797

- Kobayashi

R, Tawa A, Hanada R, Horibe K, Tsuchida M, Tsukimoto I, et al.

Extramedullary infiltration at diagnosis and prognosis in children with

acute myelogenous leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48(4):393-8. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.20824 PMid:16550530

- Muss HB, Moloney WC. Chloroma and other myeloblastic tumors. Blood. 1973;42(5):721-8. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.V42.5.721.721

- Yamauchi

K, Yasuda M. Comparison in treatments of nonleukemic granulocytic

sarcoma: report of two cases and a review of 72 cases in the

literature. Cancer. 2002;94(6):1739-46. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.10399 PMid:11920536

- Neiman

RS, Barcos M, Berard C, Bonner H, Mann R, Rydell RE, et al.

Granulocytic sarcoma: a clinicopathologic study of 61 biopsied cases.

Cancer. 1981;48(6):1426-37. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19810915)48:6<1426::AID-CNCR2820480626>3.0.CO;2-G

- Chang

H, Brandwein J, Yi QL, Chun K, Patterson B, Brien B. Extramedullary

infiltrates of AML are associated with CD56 expression, 11q23

abnormalities and inferior clinical outcome. Leuk Res.

2004;28(10):1007-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leukres.2004.01.006 PMid:15289011

- Hagen

PA, Singh C, Hart M, Blaes AH. Differential Diagnosis of Isolated

Myeloid Sarcoma: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Hematol

Rep. 2015;7(2):5709. https://doi.org/10.4081/hr.2015.5709 PMid:26330997 PMCid:PMC4508548

- Menasce

LP, Banerjee SS, Beckett E, Harris M. Extra-medullary myeloid tumour

(granulocytic sarcoma) is often misdiagnosed: a study of 26 cases.

Histopathology. 1999;34(5):391-8. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2559.1999.00651.x PMid:10231412

- Byrd

JC, Edenfield WJ, Shields DJ, Dawson NA. Extramedullary myeloid cell

tumors in acute nonlymphocytic leukemia: a clinical review. J Clin

Oncol. 1995;13(7):1800-16. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1995.13.7.1800 PMid:7602369

- Kim

NR, Lee WK, Lee JI, Cho HY. Multiple Jejunal Myeloid Sarcomas

Presenting with Intestinal Obstruction in a Non-leukemic Patient: A

Case Report with Ultrastructural Observations. Korean J Pathol.

2012;46(6):590-4. https://doi.org/10.4132/KoreanJPathol.2012.46.6.590 PMid:23323112 PMCid:PMC3540339

- Gajendra

S, Gogia A, Das P, Gupta R, Tanwar P. Acute myeloid leukemia presenting

as "bowel upset": a case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8(7):FD09-10.

- Benet

C, Gomez A, Aguilar C, Delattre C, Vergier B, Beylot-Barry M, et al.

Histologic and immunohistologic characterization of skin localization

of myeloid disorders: a study of 173 cases. Am J Clin Pathol.

2011;135(2):278-90. https://doi.org/10.1309/AJCPFMNYCVPDEND0 PMid:21228369

- Al-Khateeb

H, Badheeb A, Haddad H, Marei L, Abbasi S. Myeloid sarcoma:

clinicopathologic, cytogenetic, and outcome analysis of 21 adult

patients. Leuk Res Treatment. 2011;2011:523168. https://doi.org/10.4061/2011/523168 PMid:23213544 PMCid:PMC3505919

- Sen

F, Zhang XX, Prieto VG, Shea CR, Qumsiyeh MB. Increased incidence of

trisomy 8 in acute myeloid leukemia with skin infiltration (leukemia

cutis). Diagn Mol Pathol. 2000;9(4):190-4. https://doi.org/10.1097/00019606-200012000-00003 PMid:11129442

- Byrd

JC, Weiss RB, Arthur DC, Lawrence D, Baer MR, Davey F, et al.

Extramedullary leukemia adversely affects hematologic complete

remission rate and overall survival in patients with t(8;21)(q22;q22):

results from Cancer and Leukemia Group B 8461. J Clin Oncol.

1997;15(2):466-75. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1997.15.2.466 PMid:9053467

- Shan

M, Lu Y, Yang M, Wang P, Lu S, Zhang L, et al. Characteristics and

transplant outcome of myeloid sarcoma: a single-institute study. Int J

Hematol. 2021;113(5):682-92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12185-021-03081-2 PMid:33511548

- Dalland

JC, Meyer R, Ketterling RP, Reichard KK. Myeloid Sarcoma With

CBFB-MYH11 Fusion (inv(16) or t(16;16)) Prevails in the Abdomen. Am J

Clin Pathol. 2020;153(3):333-41. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcp/aqz168 PMid:31671434

- Antic

D, Elezovic I, Bogdanovic A, Vukovic NS, Pavlovic A, Jovanovic MP, et

al. Isolated myeloid sarcoma of the gastrointestinal tract. Intern Med.

2010;49(9):853-6. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.49.2874 PMid:20453407

- Derenzini

E, Paolini S, Martinelli G, Campidelli C, Grazi GL, Calabrese C, et al.

Extramedullary myeloid tumour of the stomach and duodenum presenting

without acute myeloblastic leukemia: a diagnostic and therapeutic

challenge. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49(1):159-62. https://doi.org/10.1080/10428190701704621 PMid:18203027

- El

H, II, Easler JJ, Ceppa EP, Shahda S. Myeloid sarcoma of the sigmoid

colon: An unusual presentation of a rare condition. Dig Liver Dis.

2017;49(11):1280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2017.05.012 PMid:28606757

- Goor

O, Goor Y, Konikoff F, Trejo L, Naparstak E. Common malignancies with

uncommon sites of presentation: case 3. Epigastric distress caused by a

duodenal polyp: a rare presentation of acute leukemia. J Clin Oncol.

2003;21(23):4458-9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2003.03.188 PMid:14645438

- Jeong

SH, Han JH, Jeong SY, Kang SY, Lee HW, Choi JH, et al. A case of

donor-derived granulocytic sarcoma after allogeneic hematopoietic stem

cell transplantation. Korean J Hematol. 2010;45(1):70-2. https://doi.org/10.5045/kjh.2010.45.1.70 PMid:21120167 PMCid:PMC2982999

- Le

Beau MM, Larson RA, Bitter MA, Vardiman JW, Golomb HM, Rowley JD.

Association of an inversion of chromosome 16 with abnormal marrow

eosinophils in acute myelomonocytic leukemia. A unique

cytogenetic-clinicopathological association. N Engl J Med.

1983;309(11):630-6. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198309153091103 PMid:6577285

- Mrad

K, Abid L, Driss M, Ben Abid H, Ben Romdhane K. Granulocytic sarcoma of

the small intestine in a child without leukemia: report of a case with

cytologic findings and immunophenotyping pitfalls. Acta Cytol.

2004;48(5):641-4. https://doi.org/10.1159/000326435 PMid:15471256

- Narayan

P, Murthy V, Su M, Woel R, Grossman IR, Chamberlain RS. Primary myeloid

sarcoma masquerading as an obstructing duodenal carcinoma. Case Rep

Hematol. 2012;2012:490438. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/490438 PMid:23243527 PMCid:PMC3517833

- Sun R, Samie AA, Theilmann L. A patient with a tumor of the ileocecal valve. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(6):1977, 2278. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2010.11.046 PMid:22033185

- Toubai

T, Kondo Y, Ogawa T, Imai A, Kobayashi N, Ogasawara M, et al. A case of

leukemia of the appendix presenting as acute appendicitis. Acta

Haematol. 2003;109(4):199-201. https://doi.org/10.1159/000070971 PMid:12853694

- Shimizu

H, Saitoh T, Hatsumi N, Takada S, Yokohama A, Handa H, et al. Clinical

significance of granulocytic sarcoma in adult patients with acute

myeloid leukemia. Cancer Sci. 2012;103(8):1513-7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1349-7006.2012.02324.x PMid:22568487 PMCid:PMC7659365

- Almond

LM, Charalampakis M, Ford SJ, Gourevitch D, Desai A. Myeloid Sarcoma:

Presentation, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk.

2017;17(5):263-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clml.2017.02.027 PMid:28342811

- Ibrahim

M, Chen R, Vegel A, Panse K, Bhyravabhotla K, Harris K, et al.

Treatment of myeloid sarcoma without bone marrow involvement with

gemtuzumab ozogamicin-containing regimen. Leuk Res. 2021;106:106583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leukres.2021.106583 PMid:33906021

- Chevallier

P, Labopin M, Cornelissen J, Socie G, Rocha V, Mohty M, et al.

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for isolated and

leukemic myeloid sarcoma in adults: a report from the Acute Leukemia

Working Party of the European group for Blood and Marrow

Transplantation. Haematologica. 2011;96(9):1391-4. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2011.041418 PMid:21685467 PMCid:PMC3166114

- Chen

WY, Wang CW, Chang CH, Liu HH, Lan KH, Tang JL, et al.

Clinicopathologic features and responses to radiotherapy of myeloid

sarcoma. Radiat Oncol. 2013;8:245. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-717X-8-245 PMid:24148102 PMCid:PMC4016483

- Xavier

SG, Fagundes EM, Hassan R, Bacchi C, Conchon M, Tabak DG, et al.

Granulocytic sarcoma of the small intestine with CBFbeta/MYH11 fusion

gene: report of an aleukaemic case and review of the literature. Leuk

Res. 2003;27(11):1063-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2126(03)00070-5

- Zhang

XH, Zhang R, Li Y. Granulocytic sarcoma of abdomen in acute myeloid

leukemia patient with inv(16) and t(6;17) abnormal chromosome: case

report and review of literature. Leuk Res. 2010;34(7):958-61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leukres.2010.01.009 PMid:20116851

- Wada

A, Kobayashi N, Asanuma S, Matsuoka S, Kosugi M, Fujii S, et al.

Repeated donor lymphocyte infusions overcome a myeloid sarcoma of the

stomach resulting from a relapse of acute myeloid leukemia after

allogeneic cell transplantation in long-term survival of more than 10

years. Int J Hematol. 2011;93(1):118-22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12185-010-0737-z PMid:21181316

- Vedy

D, Muehlematter D, Rausch T, Stalder M, Jotterand M, Spertini O. Acute

myeloid leukemia with myeloid sarcoma and eosinophilia: prolonged

remission and molecular response to imatinib. J Clin Oncol.

2010;28(3):e33-5. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.23.6976 PMid:19901109

- Gadage

V, Zutshi G, Menon S, Shet T, Gupta S. Gastric myeloid sarcoma--a

report of two cases addressing diagnostic issues. Indian J Pathol

Microbiol. 2011;54(4):832-5.

- Huang XL,

Tao J, Li JZ, Chen XL, Chen JN, Shao CK, et al. Gastric myeloid sarcoma

without acute myeloblastic leukemia. World J Gastroenterol.

2015;21(7):2242-8. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i7.2242 PMid:25717265 PMCid:PMC4326167

- Kini

S, Amarapurkar A, Balasubramanian M. Small Intestinal Obstruction with

Intussusception due to Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Case Report. Case Rep

Gastrointest Med. 2012;2012:425358. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/425358 PMid:22928122 PMCid:PMC3426187

- Koehler M. Granulocytic sarcoma of the stomach. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48(2):190. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-5107(98)70162-2

- Sekaran

A, Darisetty S, Lakhtakia S, Ramchandani M, Reddy DN. Granulocytic

Sarcoma of the Stomach Presenting as Dysphagia during Pregnancy. Case

Rep Gastrointest Med. 2011;2011:627549. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/627549 PMid:22606423 PMCid:PMC3350040

- Yu

T, Xu G, Xu X, Yang J, Ding L. Myeloid sarcoma derived from the

gastrointestinal tract: A case report and review of the literature.

Oncol Lett. 2016;11(6):4155-9. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2016.4517 PMid:27313759 PMCid:PMC4888104

- Choi

ER, Ko YH, Kim SJ, Jang JH, Kim K, Kang WK, et al. Gastric recurrence

of extramedullary granulocytic sarcoma after allogeneic stem cell

transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol.

2010;28(4):e54-5. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.23.7560 PMid:19917867

- Jalil

Ur R, Shinawi M, Aslam M, Kelta M. Acute myeloid leukemia

post-allogeneic peripheral stem cell transplant with gastric chloroma.

Ann Saudi Med. 2011;31(6):658-60. https://doi.org/10.4103/0256-4947.81805 PMid:21727746 PMCid:PMC3221145

- Pasricha TS, Abraczinskas D. Gastrointestinal Myeloid Sarcoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(9):858. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMicm2001235 PMid:32846064

- Alvarez

P, Navascues CA, Ordieres C, Pipa M, Vega IF, Granero P, et al.

Granulocytic sarcoma of the small bowel, greater omentum and peritoneum

associated with a CBFbeta/MYH11 fusion and inv(16) (p13q22): a case

report. Int Arch Med. 2011;4(1):3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1755-7682-4-3 PMid:21255400 PMCid:PMC3032668

- Chen

YI, Paci P, Michel RP, Bessissow T. Myeloid sarcoma of the duodenum: a

rare cause of bowel obstruction and gastrointestinal bleeding.

Endoscopy. 2015;47 Suppl 1 UCTN:E181-2. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0034-1391502

- Cicilet S, Tom FK, Philip B, Biswas A. Primary myeloid sarcoma of small bowel. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2017-220503 PMid:28596206 PMCid:PMC5535183

- Fukushima

M, Ono Y, Imai Y. Granulocytic sarcoma of the small intestine in a

patient with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Dig Endosc.

2014;26(6):757-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/den.12381 PMid:25251682

- Ghafoor

T, Zaidi A, Al Nassir I. Granulocytic sarcoma of the small intestine:

an unusual presentation of acute myelogenous leukaemia. J Pak Med

Assoc. 2010;60(2):133-5.

- He T, Guo Y,

Wang C, Yan J, Zhang M, Xu W, et al. A primary myeloid sarcoma

involving the small intestine and mesentery: case report and literature

review. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2018;11(8):4158-62.

- Hotta

K, Kunieda K. Granulocytic sarcoma of the jejunum diagnosed by biopsies

during double-balloon endoscopy before treatment (with video). Dig

Endosc. 2013;25(4):468. https://doi.org/10.1111/den.12107 PMid:23621465

- Huang

B, You P, Zhu P, Du Z, Wu B, Xu X, et al. Isolated duodenal myeloid

sarcoma associated with the CBFbeta/MYH11 fusion gene followed by acute

myeloid leukemia progression: A case report and literature review.

Oncol Lett. 2014;8(3):1261-4. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2014.2313 PMid:25120702 PMCid:PMC4114609

- Kitagawa

Y, Sameshima Y, Shiozaki H, Ogawa S, Masuda A, Mori SI, et al. Isolated

granulocytic sarcoma of the small intestine successfully treated with

chemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation. Int J Hematol.

2008;87(4):410-3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12185-008-0067-6 PMid:18365139

- Kumar

B, Bommana V, Irani F, Kasmani R, Mian A, Mahajan K. An uncommon cause

of small bowel obstruction: isolated primary granulocytic sarcoma. QJM.

2009;102(7):491-3. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcp051 PMid:19433489

- Lee

EY, Leung AY, Anthony MP, Loong F, Khong PL. Utility of 18F-FDG PET/CT

in identifying terminal ileal myeloid sarcoma in an asymptomatic

patient. Am J Hematol. 2011;86(12):1036-7. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.22077 PMid:21800353

- Li X, Huang C, Li Y. Obstructive jaundice caused by myeloid sarcoma in duodenal ampulla. Dig Liver Dis. 2019;51(2):321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2018.08.004 PMid:30253977

- Lim

SW, Lee HL, Lee KN, Jun DW, Kim IY, Kim E, et al. A Case of Myeloid

Sarcoma of Intestine. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2016;68(3):148-51. https://doi.org/10.4166/kjg.2016.68.3.148 PMid:27646584

- Martinelli

G, Ottaviani E, Testoni N, Visani G, Pagliani G, Tura S. Molecular

analysis of granulocytic sarcoma: a single center experience.

Haematologica. 1999;84(4):380-2.

- McKenna

M, Arnold C, Catherwood MA, Humphreys MW, Cuthbert RJ, Bueso-Ramos C,

et al. Myeloid sarcoma of the small bowel associated with a

CBFbeta/MYH11 fusion and inv(16)(p13q22): a case report. J Clin Pathol.

2009;62(8):757-9. https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.2008.063669 PMid:19638550

- Meireles

LC, Lagos AC, Marques I, Serejo F, Velosa J. Myeloid sarcoma of

gastrointestinal tract: A rare cause of obstruction. Rev Esp Enferm

Dig. 2015;107(5):326-7.

- Mizumoto R,

Tsujie M, Wakasa T, Kitani K, Manabe H, Fukuda S, et al. Isolated

myeloid sarcoma presenting with small bowel obstruction: a case report.

Surg Case Rep. 2020;6(1):2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-019-0759-6 PMid:31900687 PMCid:PMC6942080

- Morel

F, Herry A, Le Bris MJ, Le Calvez G, Marion V, Berthou C, et al.

Isolated granulocytic sarcoma followed by acute myelogenous leukemia

type FAB-M2 associated with inversion 16 and trisomies 9 and 22.

Leukemia. 2002;16(12):2458-9. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.leu.2402593 PMid:12454755

- Nemesio

RA, Costa B, Abrantes C, Leite JS. Myeloid sarcoma of the small

intestine in a patient without overt acute myeloid leukaemia: a

challenging diagnosis of a rare condition. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2017-222718 PMid:29848520 PMCid:PMC5976126

- Ono

K, Mikami Y, Hosoe N. Primary granulocytic sarcoma of the small

intestine diagnosed by single-balloon enteroscopy: A case report. Dig

Endosc. 2020;32(3):436. https://doi.org/10.1111/den.13611 PMid:31858650

- Palanivelu

C, Rangarajan M, Senthilkumar R, Annapoorni S. Laparoscopic management

of an obstructing granulocytic sarcoma of the jejunum causing

intussusception in a nonleukemic patient: report of a case. Surg Today.

2009;39(7):606-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-007-3807-y PMid:19562450

- Russell

SJ, Giles FJ, Thompson DS, Scanlon DJ, Walker H, Richards JD.

Granulocytic sarcoma of the small intestine preceding acute

myelomonocytic leukemia with abnormal eosinophils and inv(16). Cancer

Genet Cytogenet. 1988;35(2):231-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-4608(88)90245-2

- Wang

P, Li Q, Zhang L, Ji H, Zhang CZ, Wang B. A myeloid sarcoma involving

the small intestine, kidneys, mesentery, and mesenteric lymph nodes: A

case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore).

2017;96(42):e7934. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000007934 PMid:29049187 PMCid:PMC5662353

- Wong

SW, Lai CK, Lee KF, Lai PB. Granulocytic sarcoma of the small bowel

causing intestinal obstruction. Hong Kong Med J. 2005;11(3):204-6.

- Yoldas

T, Erol V, Demir B, Hoscoskun C. A rare cause of mechanical

obstruction: Intestinal myeloid sarcoma. Ulus Cerrahi Derg.

2014;30(3):176-8. https://doi.org/10.5152/UCD.2013.31 PMid:25931908 PMCid:PMC4379854

- Evans

C, Rosenfeld CS, Winkelstein A, Shadduck RK, Pataki KI, Oldham FB.

Perforation of an unsuspected cecal granulocytic sarcoma during therapy

with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. N Engl J Med.

1990;322(5):337-8. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199002013220517 PMid:2404207

- Gupta

S, Chawla I, Singh V, Singh K. Granulocytic sarcoma (chloroma)

presenting as colo-colic intussusception in a 16-year-old boy: an

unusual presentation. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2014-206138 PMid:25150243 PMCid:PMC4154025

- Kaila V, Desai A. An Unusual Cause of Postpolypectomy Bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(4):e3-e5. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.063 PMid:32205169

- Rodriguez

EA, Lopez MA, Valluri K, Wang D, Fischer A, Perdomo T. Acute

appendicitis secondary to acute promyelocytic leukemia. Am J Case Rep.

2015;16:73-6. https://doi.org/10.12659/AJCR.892760 PMid:25666852 PMCid:PMC4327184

[TOP]