Stefano Botti1*, Chiara Cannici2*, Sarah Jayne Liptrott3*, Valentina De Cecco4, Elena Rostagno5, Gianpaolo Gargiulo6, Laura Orlando7, Alessandro Caime8, Emanuela Samarani9, Letizia Galgano10, Marco Cioce11, Nicola Mordini12, Nadia Elisa Mandelli13, Lucia Tombari14, Sara Errichiello15, Nicola Celon16, Roberto Lupo17, Teresa Rea18 and Nicola Serra19.

1 Hematology Unit, Azienda USL-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, viale Risorgimento 80, 42123, Reggio Emilia, Italy.

2 Division of Hematology, Azienda Ospedaliera SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo, via Venezia 16, 15121, Alessandria, Italy.

3 Ente Ospedaliero Cantonale, Via Ospedale, Bellinzona, Switzerland.

4

Department of Onco-Haematology and Cell and Gene Therapy, Bambino Gesù

Children's Hospital IRCCS, Piazza Sant'Onofrio 4, 00165, Rome,

Italy.

5 Oncoematologia Pediatrica, IRCCS

Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria di Bologna, via Giuseppe Massarenti

13, 40138, Bologna, Italy.

6 Haematology Unit, Federico II University Hospital of Naples, via S. Pansini 5, 80131, Naples, Italy.

7 Istituto Oncologico della Svizzera Italiana, via A. Gallino 12, 6500, Bellinzona, Switzerland.

8 Division of Hemato-Oncology, European Institute of Oncology IRCCS, via Ripamonti 435, 20141, Milan, Italy.

9 Unit of Blood Diseases and Stem Cell Transplantation, ASST Spedali Civili, Piazzale Spedali Civili 1, 25100, Brescia, Italy.

10 Transfusion Medicine and Cell Therapies, AOU-Careggi, Largo Brambilla 3, 50139, Firenze, Italy.

11

Hematology and Trasplant Unit, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A.

Gemelli IRCCS, Largo Agostino Gemelli 8, 00168, Rome, Italy.

12 Hematology Division, AO S. Croce e Carle, via M. Coppino 26, 12100 Cuneo, Italy.

13 Department of Pediatrics, University of Milano-Bicocca Fondazione MBBM/ASST, via Pergolesi 33, 20900 Monza, Italy.

14

Hematology and Stem Cell Transplant Center, Azienda Ospedaliera

Ospedali Riuniti Marche Nord (AORMN), piazzale Carlo Cinelli 4, 61121

Pesaro, Italy.

15 Hematology Unit, Azienda Sanitaria

Universitaria Friuli Centrale, piazzale Santa Maria della Misericordia

15, 33100, Udine, Italy.

16 Pediatric Onco-hematology Unit, AOU Padova, via Giustiniani 2, 35128, Padova, Italy.

17 Emergency Unit, ASL Lecce “San Giuseppe da Copertino” Hospital, via Carmiano 1, 73043, Copertino Lecce, Italy.

18 Department of Public Health, University Federico II of Naples, via S. Pansini 5, 80131, Naples, Italy.

19 Department of Public Health, University Federico II of Naples, via S. Pansini 5, 80131, Naples, Italy.

Correspondence to:

Stefano Botti, BSc. Hematology Unit, Azienda USL-IRCCS di Reggio

Emilia, viale Risorgimento 80, 42123, Reggio Emilia, Italy. Tel: +39

052 229 66 61. E-mail

stefano.botti@ausl.re.it . ORCID:

0000-0002-0678-0242.

Published: January 1, 2022

Received: October 12, 2021

Accepted: December 14, 2021

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2022, 14(1): e2022010 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2022.010

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Background and objective:

Northern Italy was one of the first European territories to deal with

the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak. Drastic emergency

restrictions were introduced to contain the spread and limit pressure

on healthcare facilities. However, nurses were at high risk of

developing physical, mental, and working issues due to professional

exposure. The aim of this cross-sectional study was to investigate

these issues among nurses working in Italian hematopoietic stem cell

transplant (HSCT) centers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods:

Data were collected online immediately after the first "lockdown"

period in order to investigate the prevalence of physical issues, sleep

disorders, and burnout symptoms and explore correlations with COVID-19

territorial incidence in Northern Italian regions versus Central and

Southern Italian regions.

Results:

Three hundred and eight nurses working in 61 Italian HSCT Units

responded to the survey. Depression, cough, and fever were more

frequently reported by nurses working in geographical areas less

affected by the pandemic (p=0.0013, p<0.0001, and p=0.0005

respectively) as well as worst sleep quality (p=0.008). Moderate levels

of emotional exhaustion (mean±SD - 17.4±13.0), depersonalization

(5.3±6.1), and personal accomplishment (33.2±10.7) were reported

without significant differences between territories.

Conclusions:

different COVID-19 incidence among territories did not influence

nurses' burden of symptoms in the HSCT setting. However, burnout and

insomnia levels should be considered by health care facilities in order

to improve preventive strategies.

|

Introduction

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic rapidly affected health activities worldwide.[1]

A higher prevalence of severe complications due to COVID-19 in the

frail population, including subjects with co-morbidities such as

chronic diseases, cardio-vascular illnesses, respiratory issues, and

cancer, was well recognized.[2-7] In Italy, the

spread of the infection increased exponentially, causing high numbers

of deaths, especially in Northern Italian regions[8] after which, the whole country was placed into 'lockdown' from March 9 to May 5, 2020[9] in order to reduce virus' circulation and decrease the pressure on healthcare facilities.

As

the literature demonstrated, some pandemic-related factors such as the

danger of the disease and the adopted restrictive measures were sources

of concern and anxiety among the general population[10-14] and Health Care Professionals (HCPs), leading to increased risk of psychiatric symptoms development.[15,16] Nurses were more prone to develop burnout and stress disorders during the pandemic outbreak[17,18]

due to various factors such as their proximity with the patients, the

higher work pace, the emotional demands increasing, and the concern of

becoming infected by COVID-19 and of transmitting it to others.[19] HCPs directly involved in caring for those in a critical condition were exposed to a greater risk of becoming infected[20]

with major psychological pressure related to uncertainty about the

duration of the crisis, the lack of proven therapies or vaccines,

potential shortages of healthcare resources including personal

protective equipment, and other less estimated factors, such as

pre-existing psychological problems and work-related issues.[17,21-24] Stress disorders[25-27]

and psychological disturbances such as anxiety, depression, moral

distress, and sleep disorders were detected in HCPs treating patients

exposed to COVID-19.[21,28-33]

However, the literature showed that oncology nurses working frontline

with COVID-19 patients had a lower frequency of burnout and were less

worried about being infected than colleagues working on usual wards.[25]

Thus, few and conflicting results were reported within the cancer

setting, and no data were available for onco-hematology and

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (HSCT) settings where patients

were at higher risk of infection.[34]

The pandemic posed several challenges to onco-hematology nurses[35]

due to organizational issues, limited resources, and increasing working

time with patients exposed to severe infectious complications and

occupational risks, contributing to increased stress-related

disturbances[36] like burnout or insomnia. Burnout

(BO) is defined as a syndrome resulting from chronic workplace stress

that was not properly addressed.[37,38]

This

investigation may highlight these issues and provide useful information

regarding the need for supportive strategies for nurses.[39-41]

The

aims of this study were: 1) to investigate the prevalence of BO, sleep

disturbances, and other symptoms on nurses working in stem cell

transplantation settings, immediately after the lockdown period in

Italy; 2) to identify any differences among Italian regions according

to the different incidences of COVID-19.

Materials and Methods

A

cross-sectional study was designed to assess the prevalence of burnout,

sleep disturbances, and other symptoms of nurses working with HSCT

patients.

A presentation letter containing the link to an

online, voluntary, and anonymous survey available from June 10, 2020,

to August 15, 2020 (Google forms survey URL https://docs.google.com/forms/d/1-ZkE8WgE85HiDk5kFDyJenmZvgY82OBypwoT2I-7t_I/edit)

was sent to all nurses (n = 178) of the Gruppo Italiano Trapianto di

Midollo Osseo (GITMO) network via email. A snowballing procedure

was adopted for participants' recruitment asking participants to

involve other colleagues. The questionnaire was divided into five

sessions: three composed of structured questions (single or multiple or

scaled responses) assessing socio-demographic and professional details,

perceived COVID-19 pandemic induced working issues, HSCT nurses'

concerns and general physical and psychological symptoms experienced;

and two sessions containing validated tools evaluating burnout

prevalence (Maslach Burnout Inventory - MBI)[38] and sleep quality

(Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index - PSQI).[42,43] The first 3 sessions were developed reviewing the available literature[17,18,21,27-29]

by the Nursing Committee of GITMO and tested for understanding, clarity

and readability before the start of the study. The online system

registered only completed questionnaires.

The MBI is a validated

22 items questionnaire evaluating the 3 dimensions of BO (Emotional

Exhaustion - EE, Depersonalization - DP, and Personal Accomplishment -

PA) on the third level of severity (low, moderate, high), scored

according to the Italian Maslach Manual.[44] However,

in line with other authors, we also defined BO as a high level of

emotional exhaustion (>27) and/or a high level of depersonalization

(>10), while the frequency of low sense of PA was considered

separately (>31).[45,46]

The PSQI contains

19 self-rated questions related to 7 sub-scores; these items give a

global score from 0 to 21, where higher values (cut off = 5) are

associated with poor sleep quality. It is considered the most important

tool to assess sleep quality.

Statistical analysis was performed

stratifying results: Northern Italian regions (NIT) versus Central and

Southern Italian regions (CSIT) according to the different prevalence

of COVID-19 in these areas.

The Matrix Laboratory (MATLAB)

Statistical toolbox version 2008 (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) was used.

Descriptive analysis was performed on response frequencies; the

Chi-square test was used to evaluate significant differences between

the two groups. Fisher's exact test was used where the Chi-square test

was not appropriate. The multiple comparison chi-square test and post

hoc Z-test were used to define significant differences among

percentages for unpaired data, Mann Whitney test was used as an

alternative to the independent samples t-test for not normal

distributions. All tests with p<0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Socio-Demographic and Professional Details. Three hundred and eight nurses (82.5% women, mean age 42.2, SD±10.5),

who represented one-quarter of the total number of nurses working

in HSCT centers of Italy, provided complete responses to the

survey. According to COVID-19 disease prevalence, results were

stratified in two clusters corresponding to two geographical

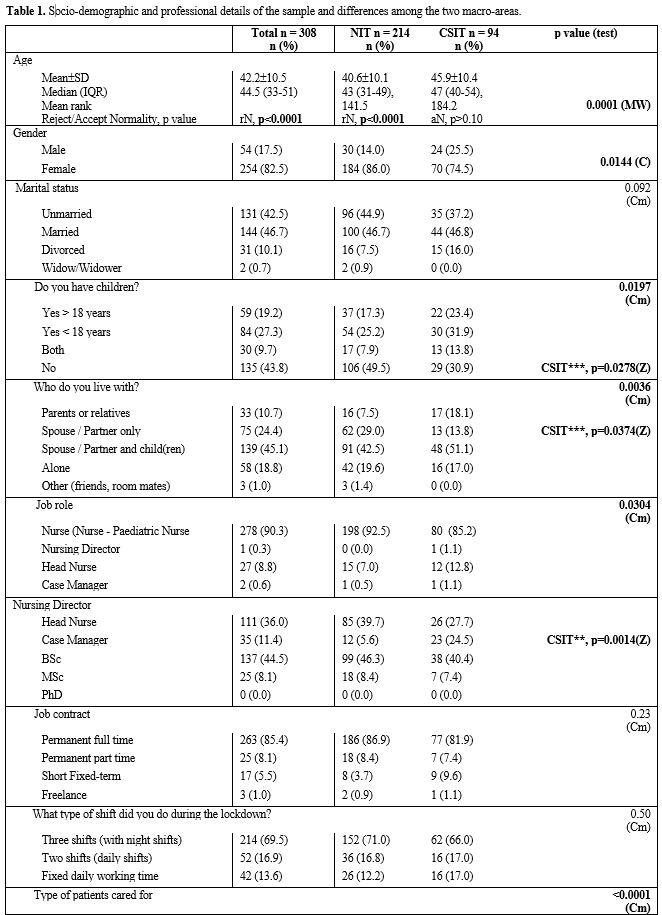

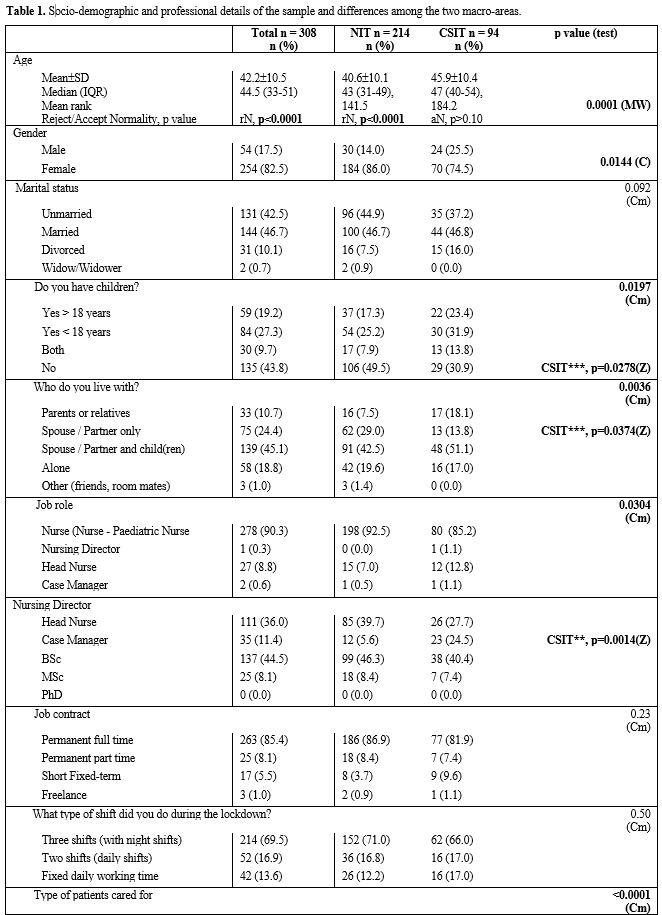

macro-areas (NIT vs. CSIT). Table 1 reports the sample characteristics and differences among sub-groups.

The

majority of respondents were female across both groups (NIT n=184,

86.0%; CSIT n=70, 74.5%) with a younger nursing population in the

NIT group (NIT Mean±SD 40.6±10.1; CSIT Mean±SD 45.9±10.4)

In the

CSIT group, significantly fewer respondents lived with a spouse or

companion (13.8%, p=0.0374) or did not have children (30.9%, p=0.0278).

The

majority of respondents were staff nurses (n=254, 82.5%), educated to

degree level (n=137, 44.5%) and in full time employment (n=263, 85.4%)

, similar across the two geographical groups.

Respondents worked

primarily with adults only (n=229, 74.3%), with fewer respondents

working with only pediatric patients, particularly less represented in

Central and Southern Italian regions (NIT n=62, 29.0% vs. CSIT n=7,

7.4%; p=0.0027), while respondents working with both pediatric and

adult patients were more commonly from CSIT areas (8.5%; p=0.0310).

Most

respondents worked in inpatient units (n=236, 74.3%) but fewer from

Central and Southern Italian regions (CSIT n=60, 63.8% vs NIT n=176,

82.2%, p=0.0109).

|

Table

1. Socio-demographic and professional details of the sample and differences among the two macro-areas. |

|

|

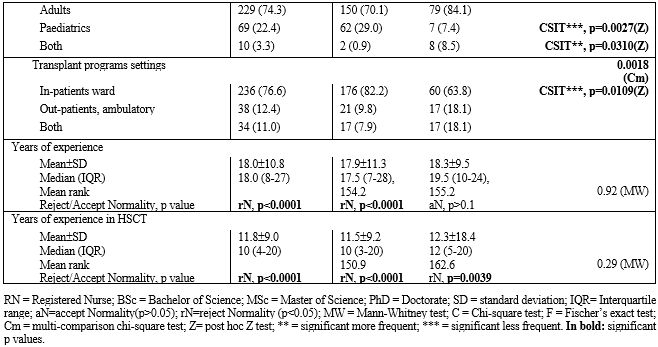

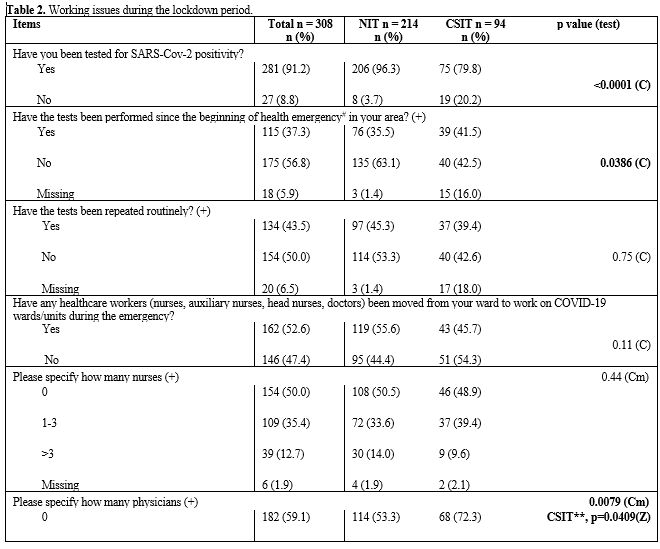

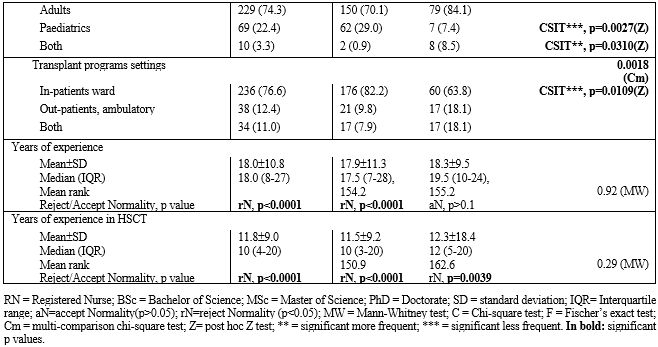

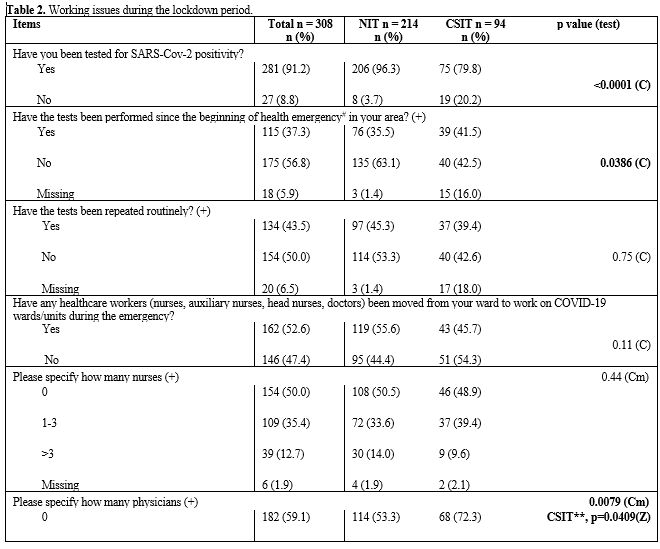

COVID-19 Pandemic Induced Working Issues. Several working issues were highlighted during the lockdown, summarised in Table 2.

At the time of this study, the majority of respondents had been tested

for SARS-CoV-2 positivity (n=281; 91.2%), significantly more in the NIT

group compared with nurses from CSIT centers (96.3% vs. 79.8%,

p<0.0001). However, tests for SARS-CoV-2 had not been performed from

the beginning of the pandemic in over half of respondents (n=175;

56.8%), more so in those from NIT regions in contrast to CSIT centers

(63.1% vs. 42.5%, p=0.0386), and tests were being repeated routinely in

less than half of respondents (134; 43.5%).

Half of the sample

(162; 52.6%) reported that nurses and physicians in their center had

been redeployed from HSCT wards to inpatient units caring for patients

affected by COVID-19 in order to deal with the emergency, more commonly

nurses rather than medical staff (n=148, 48.1% vs. n=117, 38.0%).

The movement of nurses from caring for HSCT patients to working on

COVID-19 dedicated wards was similar between regions; however,

respondents from Central and Southern regions reported that no

physicians were moved in most cases (72.3%, p=0.0409).

Sixty

percent of the respondents acknowledged having had contact with someone

positive for SARS-CoV-2, more frequently in NIT regions (64%,

p=0.0494). Little over half (n=171; 55.5%) felt they had the

appropriate availability of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) during

the lockdown period while 69.5% (n=214) felt they had received adequate

training on PPE use, significantly more in respondents from NIT centers

(74.8%, p=0.0024).

One-third of respondents (n=103; 33.4%)

reported a loss of income due to the lockdown situation, with the

majority being unable to meet close relatives in this period (263;

85.4%).

|

Table 2. Working issues during

the lockdown period. |

|

|

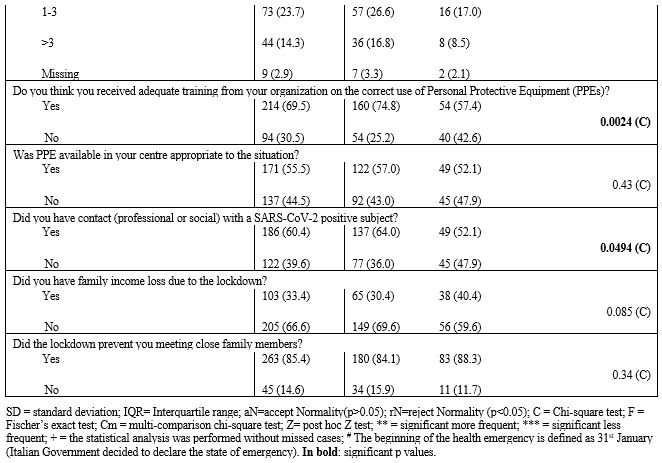

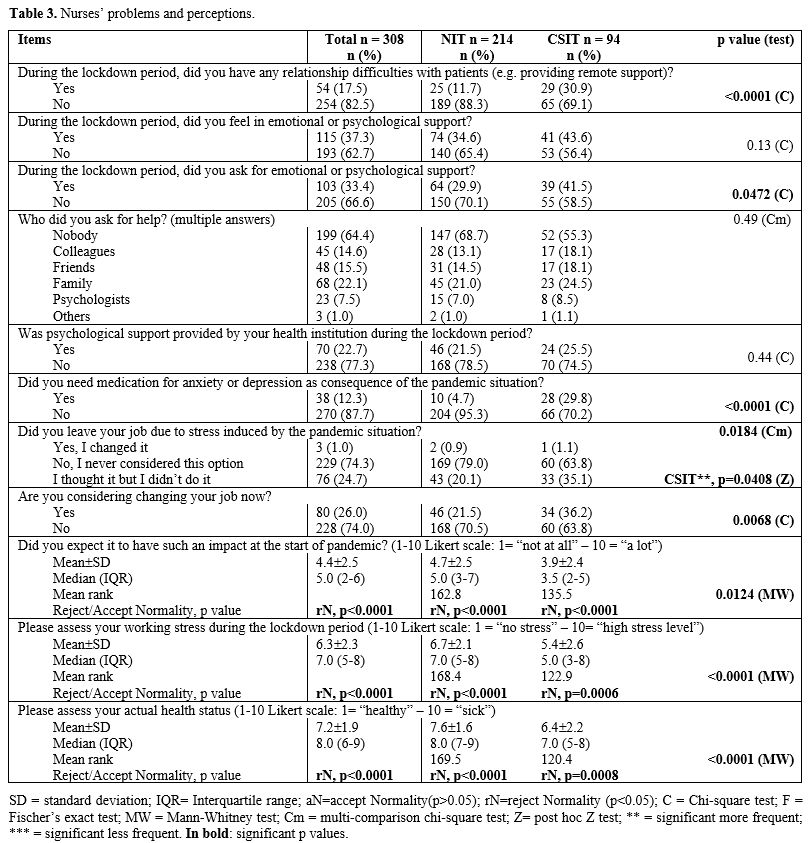

HSCT Nurses' Concerns and Symptoms.

Despite the difference in the prevalence of COVID-19 between the two

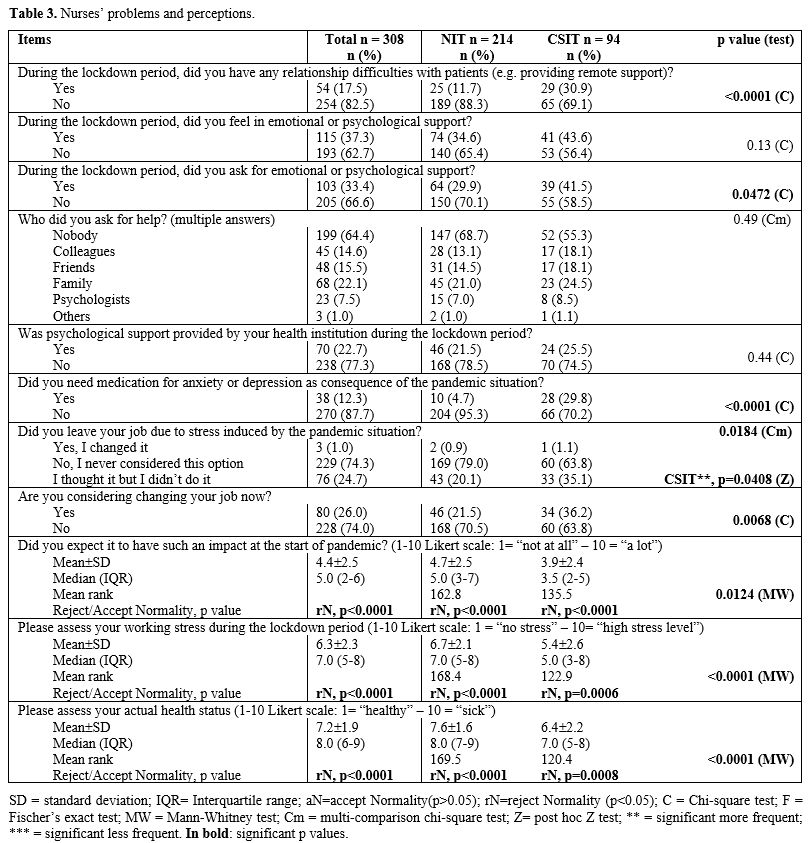

groups of regions, the effects of COVID-19 on work, physical and

psychological effects, and impact on daily life were significantly less

underestimated by CSIT HSCT nurses (p=0.0124) (Table 3).

Most nurses (n=254; 82.5%) did not experience relationship difficulties

with patients (e.g., providing remote support). However, where

reported, challenges were greater in nurses from CSIT regions (30.7%

vs. 11.9%, p>0.0001). The need for emotional or psychological

support was felt by just over one-third of respondents (n=115; 37.3%),

almost all having had support after the first wave of COVID-19 (n=103;

33.4%), particularly those from central and southern Italian regions

(CSIT 41.5% vs. NIT 29.9%, p=0.0472). Few nurses (n=23; 7.5%) asked for

formal help from a psychologist, and in less than one-quarter of

centers, psychological support was available and provided by the

institution where respondents were working (n=70; 22.7%). Thirty-eight

nurses (12.3%) reported requiring medication for anxiety or depression

induced by the pandemic situation, mostly from Central and Southern

Italian regions (CSIT 29.8% vs. NIT 4.7%, p<0.0001). Secondary

analysis on our database (not published material) showed that nurses

who had emotional or psychological support were significantly younger

(mean 40.5±10.4 vs 43.1±10.4 years; p=0.0269) than those who did not

need it.

|

Table

3. Nurses’ problems and perceptions. |

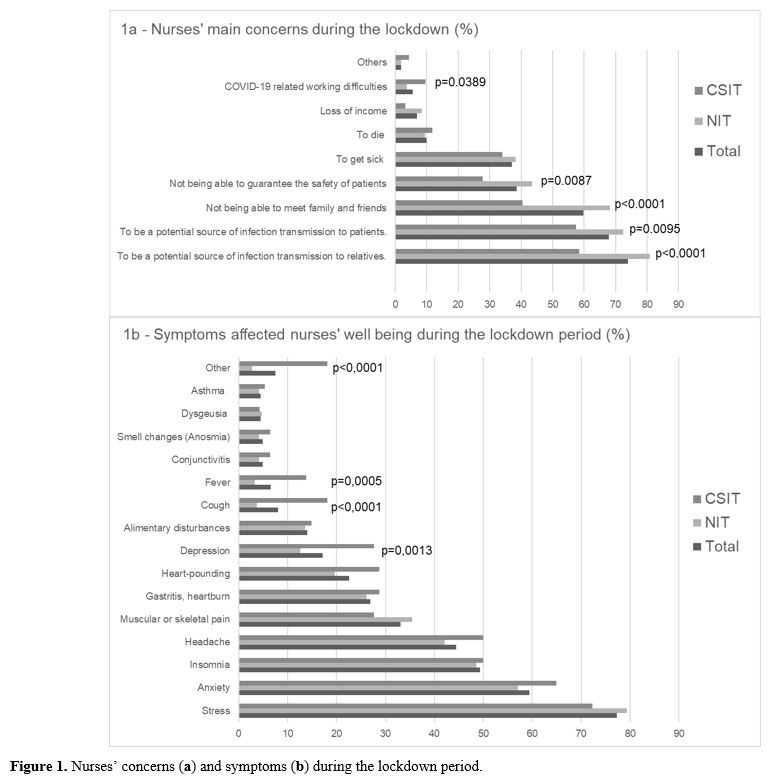

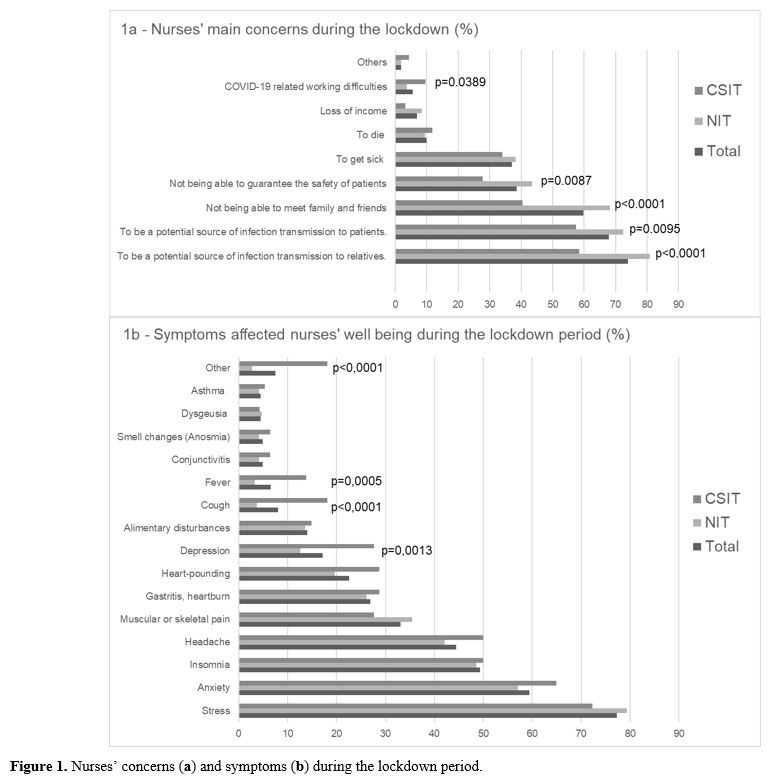

During the lockdown period, nurses' main concerns (Figure 1a)

were both the risks of transmitting infections to relatives (n=228,

74.0%) or patients (n=209; 67.9%), being a particular concern for those

working in NIT regions (p<0.0001 and p=0.0095 respectively). The

impossibility to meet family and friends (n=184; 59.7%) and concern

being unable to ensure patients' safety (n=119; 38.6%) were other

important factors, especially in the NIT area (p<0.0001 and p=0.0087

respectively). No significant difference was found regarding the fear

of developing COVID-19 between the groups.

The key physical and psychological symptoms reported by nurses’ during the lockdown period (Figure 1b)

included stress (n=238; 77.3%), anxiety (n=183; 59.4%), insomnia

(n=152; 49.3%), headache (n=137; 44.5%), muscular and skeletal pain

(n=102; 33.1%), gastritis and indigestion (n=83; 26.9%), palpitations

(n=69; 22.6%), and changes in eating habit (e.g. over/ under eating)

(n=43; 14.0%). No significant differences between groups were observed.

Depression (n=53; 17.2%), fever and cough were more frequently reported

in respondents from CSIT regions (p=0.0013; p=0.0005 and p<0.0001

respectively) as well as other minor symptoms (p<0.0001). Minor

symptoms listed included physical: (breathing difficulty, unrefreshing

sleep, extrasystole, restlessness, itching, nocturia, hunger,

menopause), social (loud noises, family problems, noisy neighbors,

children not sleeping, buying a home), and emotional (anxiety, suicidal

thoughts, fear of contagion, uncertainty, fear of not emotionally

overcoming the period, bereavement, fear of dying, pain, crowded mind).

|

Figure 1. Nurses’ concerns (a) and symptoms (b) during the lockdown period. |

A

Likert scale rating working stress during the lockdown period (1 = no

stress to 10 = worst stress imaginable), a median score of 7 (IQR 5-8)

was observed, significantly higher in NIT regions (p<0.0001).

However, three-quarters of nurses did not consider changing their job

during the lockdown period (n=229; 74.3%) or at the time of completing

the questionnaire (n=228; 74.0%), especially in NIT centers

(p=0.0068). NIT nurses mainly considered this option both during

the lockdown period and afterward (p=0.0408 and p=0.0068) (Table 3).

The median score of respondents' self-assessed actual health status at

the time of the questionnaire was 8 (IQR 6-9) on a 1 to 10 Likert

scale, being significantly higher in nurses from NIT regions

(p<0.0001).

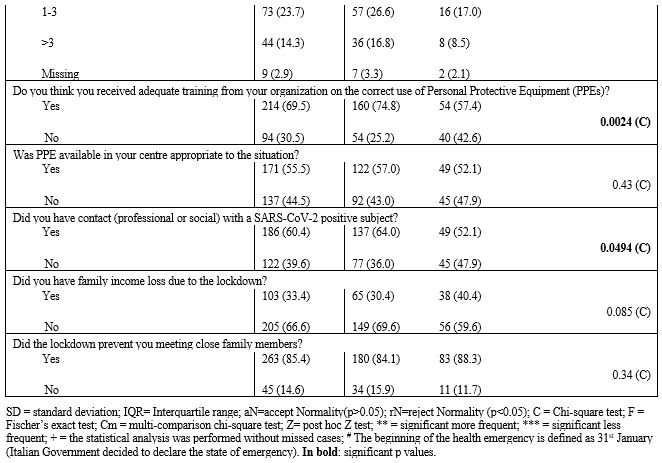

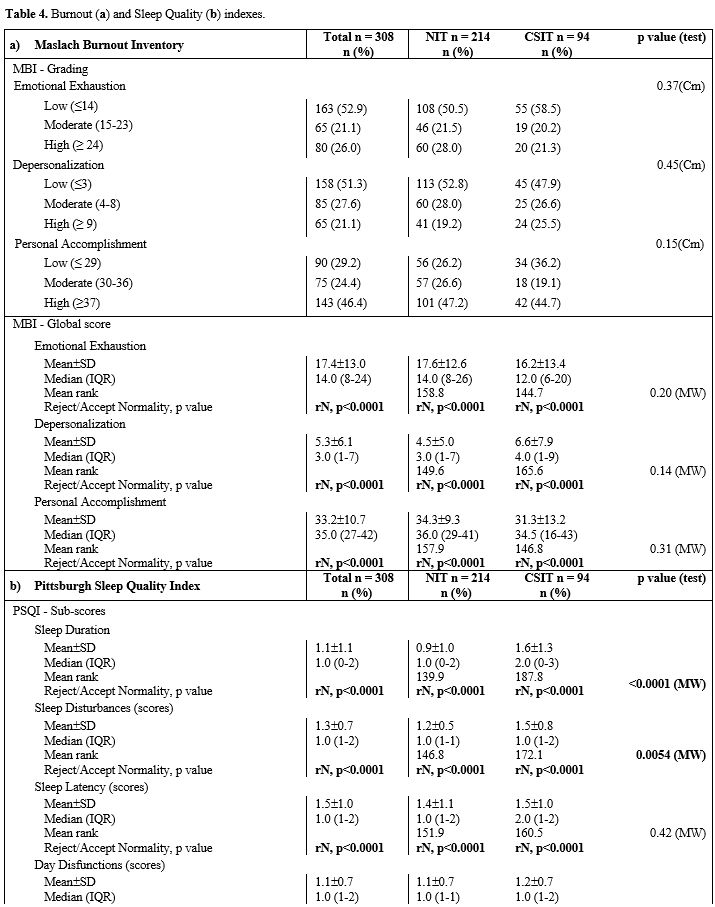

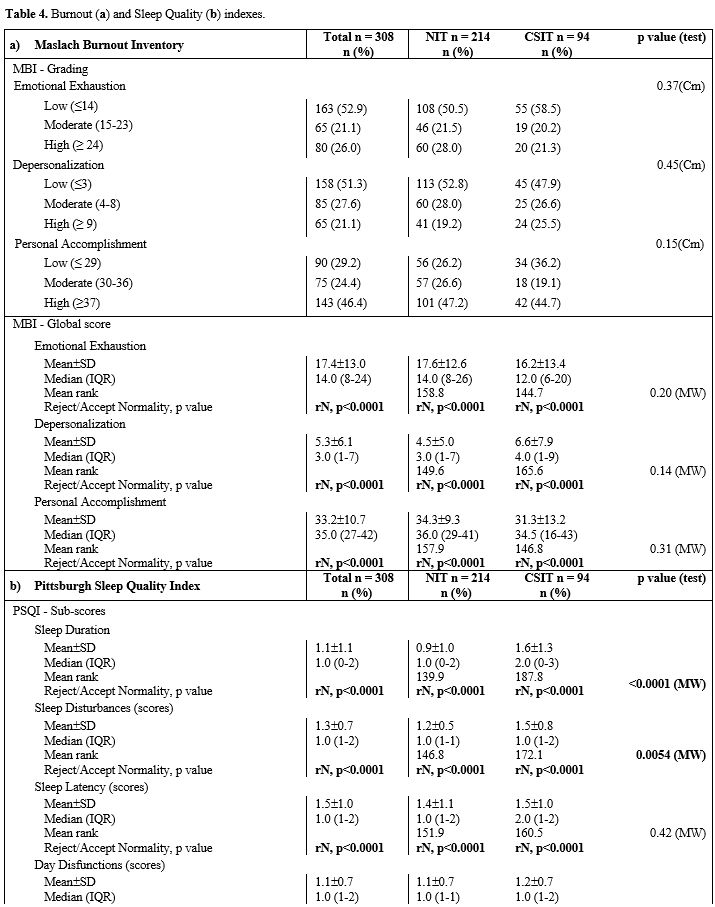

Burnout.

BO (high EE and/or high DP) was present in 76 respondents (24.7%), with

52 from NIT regions and 24 from CSIT regions (24.3% and 25.5%,

respectively); however, findings were not statistically significant. PA

was low in almost one-third of nurses (n=95, 30.8%), with greater

incidence in Central and Southern Italian regions (NIT n=61, 28.5% vs.

CSIT n=34, 36.2%), without significant p-value.

According to the reference scores,[47] mean EE was 17.4 (SD±13.0), DP was 5.3 (SD±6.1), and PA was 33.2 (SD±10.7),

showing a moderate level of BO on all three dimensions of the total

sample. Less than half of the nurses (n=163; 52.9%) reported low levels

of EE, and a quarter (n=80; 26.0%) reported high levels. DP was high in

65 participants (21.1%) and low in half of them (n=158; 51.3%), while

PA was high in 143 respondents (46.4%) and low in just under one-third

of the total sample (n=90; 29.2%). No significant differences were

observed on global scores or on severity grading between nurses working

in the different geographical regions (Table 4a).

In a secondary analysis (not published material), nurses who have had

emotional or psychological support during the lockdown period reported

a higher level of DP (p=0.0003) and EE (p<0.0001). Of them, those

who received professional support from psychiatrists or psychologists

showed significantly higher levels of EE (p=0.007) and PA (p=0.0167).

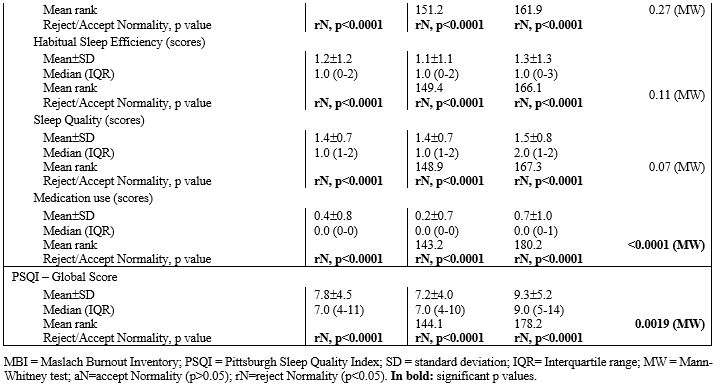

Sleep Quality. The Median PSQI global score was 7.0 (Mean 7.8; SD±4.5).

Of the 308 participants, 194 (63%) had a PSQI global score higher than

5, indicating poor sleep quality. Sixty of them (63.8%) worked in

Central and Southern Italian centers and 134 (62.6%) in Northern

centers. A statistically significant difference was found on the PSQI

values global score, where the nurses of the Central and Southern

regions referred to worse sleep quality (p=0.0019). This difference was

supported by all PSQI sub-scores, particularly by the "Sleep Duration"

score (p<0.0001), "Sleep Disturbances" score (p=0.0054), and

"Medication Use" score (p<0.0001) (Table 4b).

In addition, nurses who have had emotional or psychological support and

those who received professional support showed significantly higher

levels of PSQI global score (p<0.0001 and p=0.0017, respectively).

|

Table 4. Burnout (a) and Sleep Quality (b) indexes. |

Discussion

This

study aimed to evaluate the impact of COVID-19 on HSCT nurses' burnout,

sleep disorders, symptoms, and their distribution across Italian

regions. Assuming that during health emergencies, the psychological

stress of HCPs is expected to increase, thus favoring burnout and other

psychological issues.[32,48]

A

previous study[49] highlighted that patients developing COVID-19 were

managed by intensive care units or COVID-19 dedicated services. This

meant that HSCT nurses responding to our survey continued to work in

COVID-19 free wards. Considering the high competency level for

infection control from HSCT nurses and their skills in using PPEs

during daily practice,[49] it may be reasonable to

consider that HSCT nurses are at a lower risk of hospital contagion.

However, emergency-related factors may have increased emotional strains

and physical exhaustion, leading to faster burnout.[35,36]

As

described above, the main concerns of nurses during the lockdown period

were related to isolation from family and friends and the risk of being

a potential source of infection transmission to patients or relatives,

while nurses' own fear of becoming ill themselves appeared a secondary

issue. These findings confirm the high sense of responsibility that

characterized nurses during the pandemic.[50-52]

In

this study, nurses reported a moderate to high level of health status

and a moderate level of stress. However, stress prevalence was high in

our sample and major symptoms reported by nurses such as anxiety,

headache, heartburn, joint pain, palpitations, and sleep disturbances,

seemed to be part of an important burden of psychological disturbances

due to stress, as reported in the literature.[52] In

addition, our results highlighted the discrepancy among the nurses'

need for psychological support and the options offered by their

institutions, which may have conditioned the direction of nurses'

request for help, opting for informal rather than formal aid. During

and after the lockdown period, psychiatric services were closed or

switched to telemedicine activity in many health care facilities,[23] causing access difficulties and negatively impacting psychiatrists' supportive, educational and triaging role.[53]

The global prevalence of burnout observed according to Shanafelt's MBI scoring[45] was not comparable to previously reported data on palliative home care nurses[54] and oncology ward nurses.[25] Significant lower BO frequencies than in the past[55,56]

were shown in this study despite the recruited population being at

higher risk of psychological issues developing due to the pandemic.

However, a lower prevalence of EE was clearly reported while other

dimensions were controversial. Comparing our results with those

provided by literature was difficult due to different settings, tools,

and scoring systems used and the wide range of variables influencing

BO.

In our study, no significant differences were found over the

three-dimension BO severity grading among clustered regions, and no

differences were found calculating BO according to other criteria.[45]

Barello and colleagues[57]

reported frequencies and mean values of high-level EE and DP of a

frontline HCP cohort significantly higher than our study, suggesting a

higher prevalence of burnout among them. Authors also reported a lower

frequency of low PA than findings from this study, confirming the

results of other studies on this particular dimension.[21,25,54]

Similar findings were obtained comparing our results with another study

involving nurses working in various settings in the northwest of Italy

with different exposition to the virus.[58]

In contrast, various studies reported lower levels of BO in frontline HCPs compared with those working in COVID-free settings[25,59] or with the pre-pandemic situation.[55]

It may be assumed that the real impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on

burnout remains unclear due to many variables, including the

characteristics of the targeted sample.[56,60-62]

Sleep

disturbances are one of the most frequently reported disorders of the

psychological sphere described as a consequence of the COVID-19

pandemic in HCPs[33,63,64] and are correlated with anxiety increasing, reduction in self-efficacy,[65] and depression development in nurses.[65]

Our study confirmed insomnia as one of the more frequent symptoms

referred by HSCT nurses, and poor sleep quality was reported in

two-thirds of participants. However, no differences were found among

territories on the number of participants with poor sleep quality and

the scored mean values of PSQI, suggesting that a higher incidence of

COVID-19 did not impact this dimension of nurses' quality of life. Our

findings provided information on a specific set of care that may be

useful to understand better the situation experienced by HCPs working

in COVID-19, not-exposed environments. As reported in the literature,

health care facilities directions and policymakers should consider the

consequence of restrictive measures as well as other pandemic-related

economic and social factors on nurses' mental health, keeping in mind

that the development of stress-related issues and/or mental

disturbances in this population did not appear necessarily linked to

their proximity with the infected patients, and it could decrease the

compliance to the protective measures.[66-68]

This

study has various limitations. The cross-sectional design described a

situation in a short time frame, providing a valuable insight but not

allowing the evolving COVID-19 related situation understanding. No data

were collected on pre-existing situations preventing inferential

considerations regarding BO and sleep disorders. Moreover, to limit the

questionnaire size, some aspects such as work problems and physical and

psychological issues were recognized using not validated tools. Various

factors may prevent the generalization of our results, including the

particularities of COVID-19 spread across Italy and the organization of

the National Health System on a regional basis. Some differences among

the two groups (NIT and CSIT) may act as confounders, such as age,

gender, family conditions, job role, and working setting. Finally, all

the data were collected online.

Conclusions

This

study is the first performed in the HSCT setting, providing valuable

information regarding BO, sleep disturbances, and symptoms experienced

by nurses.

Our results provided evidence of nurses' concerns and

psycho-somatic manifestations during the first phase of the COVID-19

pandemic in Italy. These findings would suggest that different

prevalence of COVID-19 on geographical regions did not have an impact

on burnout and sleep quality. Nevertheless, the health institutions

should carefully consider the reported frequency of these issues and

the high prevalence of other stress-related symptoms to plan and

prioritize adequate supportive interventions for nurses.

Acknowledgments

All

authors would like to thanks the colleagues of GITMO network who

participated in this study. Particularly, we would like to thanks

Professor Fabio Ciceri and the members of the GITMO Board.

References

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease

(COVID-2019) situation reports. Situation report – 51. March 11, 2020.

Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/situation-report---51 Accessed January 17, 2021.

- European Commission. Joint European Roadmap towards lifting COVID-19 containment measures. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/communication_-_a_european_roadmap_to_lifting_coronavirus_containment_measures_0.pdf . Accessed January 17, 2021.

- Istituto

Superiore di Sanità. Report sulle caratteristiche dei pazienti deceduti

positivi a COVID-19 in Italia del 20 Marzo 2020. Available at: https://www.iss.it/documents/20126/0/Report+per+COVID_20_3_2019.pdf/f4d20257-53d5-eb89-087e-285e2cadf44f?t=1584724121898. Accessed January 20, 2021.

- Huang

X, Wei F, Hu L, Wen L, Chen K. Epidemiology and clinical

characteristics of COVID-19. Arch Iran Med. 2020 April 1;23(4):268-271.

https://doi.org/10.34172/aim.2020.09

- Zhou

G, Chen S. & Chen Z. Advances in COVID-19: the virus, the

pathogenesis, and evidence-based control and therapeutic strategies.

Front. Med. 14, 117–125 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11684-020-0773-x

- Wang

D, Hu B, HU C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, Wang B, Xiang H, Cheng Z, Xiong

Y, Zhao Y, Li Y, Wang X, Peng Z. Clinical characteristics of 138

hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in

Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061-1069. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.1585

- Guan

W, Ni Z, Hu Y. Clinical characteristics of 2019 novel coronavirus

infection in China. New England Journal of Medicine

https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2002032

- Istituto

Superiore di Sanità, Istituto Nazionale di Statistica. Impatto

dell’epidemia covid-19 sulla mortalità totale della popolazione

residente periodo gennaio-novembre 2020. December 30, 2020. Available

at: https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/252168 Accessed January 20, 2021.

- Presidenza

del Consiglio dei Ministri. Decreto del Presidente del Consiglio Dei

Ministri, 8 Marzo 2020. Ulteriori disposizioni attuative del

decreto-legge 23 febbraio 2020, n. 6, recante misure urgenti in materia

di contenimento e gestione dell'emergenza epidemiologica da COVID-19.

(20A01522) Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana. Anno 161° -

Numero 59 del 08-03-2020. Available at: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2020/03/08/20A01522/sg Accessed January 20, 2021

- Riaz

M, Abid M, Bano Z. Psychological problems in general population during

covid-19 pandemic in Pakistan: role of cognitive emotion regulation.

Ann Med. 2021 Dec;53(1):189-196. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2020.1853216

- Ren

SY, Wang WB, Hao YG, Zhang HR, Wang ZC, Chen YL, Gao RD. Stability and

infectivity of coronaviruses in inanimate environments. World J Clin

Cases. 2020 Apr 26;8(8):1391-1399. https://doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i8.1391

- Tyson

RC, Hamilton SD, Lo AS, Baumgaertner BO, Krone SM. The timing and

nature of behavioural responses affect the course of an epidemic. Bull

Math Biol. 2020 January 14;82(1):14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11538-019-00684-z

- Abdulkareem

SA, Augustijn EW, Filatova T, Musial K, Mustafa YT. Risk perception and

behavioral change during epidemics: Comparing models of individual and

collective learning. PLoS One. 2020 Jan 6;15(1):e0226483. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0226483

- Fiorillo

A, Sampogna G, Giallonardo V, Del Vecchio V, Luciano M, Albert U,

Carmassi C, Carrà G, Cirulli F, Dell'Osso B, Nanni MG, Pompili M, Sani

G, Tortorella A, Volpe U. Effects of the lockdown on the mental health

of the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy:

Results from the COMET collaborative network. Eur Psychiatry. 2020 Sep

28;63(1):e87. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.89

- Marazziti D, Stahl SM. The relevance of COVID-19 pandemic to psychiatry. World Psychiatry. 2020 Jun;19(2):261. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20764

- Fiorillo

A, Gorwood P. The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental

health and implications for clinical practice. Eur Psychiatry. 2020 Apr

1;63(1):e32. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.35

- Lai

J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, Wei N, Wu J, Du H, Chen T, Li R, Tan H,

Kang L, Yao L, Huang M, Wang H, Wang G, Liu Z, Hu S. Factors associated

with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to

coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Mar 2;3(3):e203976. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976.

- Cai

H, Tu B, Ma J, Chen L, Fu L, Jiang Y, Zhuang Q. Psychological impact

and coping strategies of frontline medical staff in Hunan between

January and March 2020 during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019

(COVID‑19) in Hubei, China. Med Sci Monit. 2020 Apr 15;26:e924171. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.924171

- Moreno

Martínez M, Fernández-Cano MI, Feijoo-Cid M, Llorens Serrano C, Navarro

A. Health outcomes and psychosocial risk exposures among healthcare

workers during the first wave of the COVID-19 outbreak. Saf Sci. 2022

Jan;145:105499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2021.105499

- Elfström

KM, Blomqvist J, Nilsson P, Hober S, Pin E, Månberg A, Pimenoff VN,

Arroyo Mühr LS, Lundgren KC, Dillner J. Differences in risk for

SARS-CoV-2 infection among healthcare workers. Prev Med Rep. 2021

Dec;24:101518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101518

- Trumello

C, Bramanti SM, Ballarotto G, Candelori C, Cerniglia L, Cimino S,

Crudele M, Lombardi L, Pignataro S, Viceconti ML, Babore A.

Psychological adjustment of healthcare workers in Italy during the

covid-19 pandemic: differences in stress, anxiety, depression, burnout,

secondary trauma, and compassion satisfaction between frontline and

non-frontline professionals. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Nov

12;17(22):8358. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228358

- Wang

Y, Kala MP, Jafar TH. Factors associated with psychological distress

during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on the

predominantly general population: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020 Dec 28;15(12):e0244630. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244630

- Unützer J, Kimmel RJ, Snowden M. Psychiatry in the age of COVID-19. World Psychiatry. 2020 Jun;19(2):130-131. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20766

- Gorwood

P, Fiorillo A. One year after the COVID-19: What have we learnt, what

shall we do next? Eur Psychiatry. 2021 Feb 15;64(1):e15. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.9

- Wu

Y, Wang J, Luo C, Hu S, Lin X, Anderson AE, Bruera E, Yang X, Wei S,

Qian Y. A Comparison of burnout frequency among oncology physicians and

nurses working on the frontline and usual wards during the COVID-19

epidemic in Wuhan, China. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020

Jul;60(1):e60-e65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.008

- Jakovljevic

M. COVID-19 crisis as a collective hero's journey to better public and

global mental health. Psychiatr Danub. 2020 Spring;32(1):3-5. https://doi.org/10.24869/psyd.2020.3

- Lee

SA, Jobe MC, Mathis AA, Gibbons JA. Incremental validity of

coronaphobia: Coronavirus anxiety explains depression, generalized

anxiety, and death anxiety. J Anxiety Disord. 2020 Aug;74:102268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102268 Epub 2020 July 1

- Raj

R, Koyalada S, Kumar A, Kumari S, Pani P, Nishant, Singh KK.

Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers in

India: An observational study. J Family Med Prim Care. 2020 Dec

31;9(12):5921-5926. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1217_20

- He

Q, Fan B, Xie B, Liao Y, Han X, Chen Y, Li L, Iacobucci M, Lee Y, Lui

LMW, Lu L, Guo C, McIntyre RS. Mental health conditions among the

general population, healthcare workers and quarantined population

during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Psychol Health

Med. 2020 Dec 30:1-13. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2020.1867320

- Wanigasooriya

K, Palimar P, Naumann DN, Ismail K, Fellows JL, Logan P, Thompson CV,

Bermingham H, Beggs AD, Ismail T. Mental health symptoms in a cohort of

hospital healthcare workers following the first peak of the COVID-19

pandemic in the UK. BJPsych Open. 2020 Dec 29;7(1):e24. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2020.150

- Gupta

B, Sharma V, Kumar N, Mahajan A. Anxiety and sleep disturbances among

health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in india:

cross-sectional online survey. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020 Dec

22;6(4):e24206. https://doi.org/10.2196/24206

- Pappa

S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Giannakoulis VG, Papoutsi E, Katsaounou P.

Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare

workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 Aug; 88:901-907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026

- Al

Maqbali M, Al Sinani M, Al-Lenjawi B. Prevalence of stress, depression,

anxiety and sleep disturbance among nurses during the COVID-19

pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2021

Feb;141:110343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110343

- Passamonti

F, Cattaneo C, Arcaini L, Bruna R, Cavo M, Merli F, Angelucci E,

Krampera M, Cairoli R, Della Porta MG, Fracchiolla N, Ladetto M,

Gambacorti Passerini C, Salvini M, Marchetti M, Lemoli R, Molteni A,

Busca A, Cuneo A, Romano A, Giuliani N, Galimberti S, Corso A, Morotti

A, Falini B, Billio A, Gherlinzoni F, Visani G, Tisi MC, Tafuri A, Tosi

P, Lanza F, Massaia M, Turrini M, Ferrara F, Gurrieri C, Vallisa D,

Martelli M, Derenzini E, Guarini A, Conconi A, Cuccaro A, Cudillo L,

Russo D, Ciambelli F, Scattolin AM, Luppi M, Selleri C, Ortu La Barbera

E, Ferrandina C, Di Renzo N, Olivieri A, Bocchia M, Gentile M, Marchesi

F, Musto P, Federici AB, Candoni A, Venditti A, Fava C, Pinto A,

Galieni P, Rigacci L, Armiento D, Pane F, Oberti M, Zappasodi P, Visco

C, Franchi M, Grossi PA, Bertù L, Corrao G, Pagano L, Corradini P;

ITA-HEMA-COV Investigators. Clinical characteristics and risk factors

associated with COVID-19 severity in patients with haematological

malignancies in Italy: a retrospective, multicentre, cohort study.

Lancet Haematol. 2020 Oct;7(10):e737-e745. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30251-9

- Paterson

C, Gobel B, Gosselin T, Haylock PJ, Papadopoulou C, Slusser K,

Rodriguez A, Pituskin E. Oncology nursing during a pandemic: critical

reflections in the context of COVID-19. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2020

Jun;36(3):151028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2020.151028

- Sasangohar

F, Moats J, Mehta R, Peres SC. Disaster Ergonomics: Human Factors in

COVID-19 pandemic emergency management. Hum Factors. 2020

Nov;62(7):1061-1068. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018720820939428.

- World Health Organization. Burn-Out an "Occupational Phenomenon:" International Classification of Diseases. Available at: https://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/burn-out/en/ Accessed January 26, 2021

- Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organiz Behav. (1981) 2:99–113. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030020205

- Kang

L, Li Y, Hu S, Chen M, Yang C, Yang BX, Wang Y, Hu J, Lai J, Ma X, Chen

J, Guan L, Wang G, Ma H, Liu Z. The mental health of medical workers in

Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019 novel coronavirus. Lancet

Psychiatry. 2020 Mar;7(3):e14. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30047-X

- Xiang

YT, Jin Y, Cheung T. Joint international collaboration to combat mental

health challenges during the coronavirus disease 2019 Pandemic. JAMA

Psychiatry. 2020 Oct 1;77(10):989-990. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1057

- Mo

Y, Deng L, Zhang L, Lang Q, Pang H, Liao C, Wang N, Tao P, Huang H.

Anxiety of Nurses to support Wuhan in fighting against COVID-19

epidemic and its correlation with work stress and self-efficacy. J Clin

Nurs. 2021 Feb;30(3-4):397-405. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15549

- Buysse

DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh

Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and

research. Psychiatry Res. 1989 May;28(2):193-213. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4

- Curcio

G, Tempesta D, Scarlata S, Marzano C, Moroni F, Rossini PM, Ferrara M,

De Gennaro L. Validity of the Italian version of the Pittsburgh Sleep

Quality Index (PSQI). Neurol Sci. 2013 Apr;34(4):511-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-012-1085-y

- Sirigatti

S, Stefanile C. MBI Maslach Burnout Inventory: adattamento e taratura

per l’Italia. In: MBI Maslach Burnout Inventory Manuale. Florence,

Italy: OS Organizzazioni Speciali, 1993:33e42

- Shanafelt

TD, Boone S, Tan L, Dyrbye LN, Sotile W, Satele D, West CP, Sloan J,

Oreskovich MR. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US

physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012

October 8;172(18):1377-85. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199

- Reddy

SK, Yennu S, Tanco K, Anderson AE, Guzman D, Ali Naqvi SM, Sadaf H,

Williams J, Liu DD, Bruera E. Frequency of burnout among palliative

care physicians participating in a continuing medical education course.

J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020 Jul;60(1):80-86.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.02.013

- Sirigatti

S, Stefanile C. Aspetti e problemi dell’adattamento italiano del MBI.

Bollettino di Psicologia Applicata, 1992. 202-203, 3-12.

- Adibe

B, Perticone K, Hebert C. Creating Wellness in a pandemic: a Practical

Framework for health systems responding to Covid-19. NEJM Catal 2020. https://doi.org/10.1056/CAT.20.0218

- Botti

S, Serra N, Castagnetti F, Chiaretti S, Mordini N, Gargiulo G, Orlando

L. Hematology patient protection during the covid-19 pandemic in italy:

a nationwide nursing survey. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2021 Jan

1;13(1):e2021011. https://doi.org/10.4084/MJHID.2021.011

- Barello

S, Palamenghi L, Graffigna G. Stressors and resources for healthcare

professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic: lesson learned from Italy.

Front Psychol. 2020 October 8;11:2179. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02179

- Launer J. Burnout in the age of COVID-19. Postgrad Med J. 2020 Jun;96(1136):367-368. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-137980

- Alharbi

J, Jackson D, Usher K. The potential for COVID-19 to contribute to

compassion fatigue in critical care nurses. J Clin Nurs. 2020

Aug;29(15-16):2762-2764. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15314

- Stewart

DE, Appelbaum PS. COVID-19 and psychiatrists' responsibilities: a WPA

position paper. World Psychiatry. 2020 Oct;19(3):406-407. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20803

- Varani

S, Ostan R, Franchini L, Ercolani G, Pannuti R, Biasco G, Bruera E.

Caring advanced cancer patients at home during COVID-19 outbreak:

burnout and psychological morbidity among palliative care professionals

in Italy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021 Feb;61(2):e4-e12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.11.026

- Vagliano

L, Ricceri F, Dimonte V, Scarrone S, Fiorillo L, Buono S, Del Giudice

E, Conti F, Orlando L, Mammoliti S, Alberani F. Il burnout e il rischio

di burnout nelle equipe di trapianto di midollo osseo: uno studio

multicentrico italiano [Burnout and risk of burnout in the teams of

bone marrow transplant: a multicentre Italian survey]. Assist Inferm

Ric. 2016 Jan-Mar;35(1):6-15. Italian. https://doi.org/10.1702/2228.24010 PMID: 27183420.

- Bressi

C, Manenti S, Porcellana M, Cevales D, Farina L, Felicioni I, Meloni G,

Milone G, Miccolis IR, Pavanetto M, Pescador L, Poddigue M, Scotti L,

Zambon A, Corrao G, Lambertenghi-Deliliers G, Invernizzi G.

Haemato-oncology and burnout: an Italian survey. Br J Cancer. 2008 Mar

25;98(6):1046-52. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6604270 Epub 2008 Feb 19. PMID:18283310; PMCID: PMC2275477

- Barello

S, Palamenghi L, Graffigna G. Burnout and somatic symptoms among

frontline healthcare professionals at the peak of the Italian COVID-19

pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020 Aug;290:113129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113129

- Naldi

A, Vallelonga F, Di Liberto A, Cavallo R, Agnesone M, Gonella M, Sauta

MD, Lochner P, Tondo G, Bragazzi NL, Botto R, Leombruni P. COVID-19

pandemic-related anxiety, distress and burnout: prevalence and

associated factors in healthcare workers of North-West Italy. BJPsych

Open. 2021 Jan 7;7(1):e27. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2020.161

- Dimitriu

MCT, Pantea-Stoian A, Smaranda AC, Nica AA, Carap AC, Constantin VD,

Davitoiu AM, Cirstoveanu C, Bacalbasa N, Bratu OG, Jacota-Alexe F,

Badiu CD, Smarandache CG, Socea B. Burnout syndrome in Romanian medical

residents in time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Med Hypotheses. 2020

Nov;144:109972. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109972

- Sharifi

M, Asadi-Pooya AA, Mousavi-Roknabadi RS. Burnout among healthcare

providers of COVID-19; a systematic review of epidemiology and

recommendations. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2020 December 10;9(1):e7.

- Pfefferbaum B, North CS. Mental Health and the Covid-19 Pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020 Aug 6;383(6):510-512. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2008017

- Grassi

L, Magnani K. Psychiatric morbidity and burnout in the medical

profession: an Italian study of general practitioners and hospital

physicians. Psychother Psychosom. 2000 Nov-Dec;69(6):329-34. https://doi.org/10.1159/000012416

- Forrest

CB, Xu H, Thomas LE, Webb LE, Cohen LW, Carey TS, Chuang CH, Daraiseh

NM, Kaushal R, McClay JC, Modave F, Nauman E, Todd JV, Wallia A, Bruno

C, Hernandez AF, O'Brien EC; HERO Registry Research Group. Impact of

the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic on US healthcare workers:

Results from the HERO registry. J Gen Intern Med. 2021 Mar 10:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06529-z

- Simonetti

V, Durante A, Ambrosca R, Arcadi P, Graziano G, Pucciarelli G, Simeone

S, Vellone E, Alvaro R, Cicolini G. Anxiety, sleep disorders and

self-efficacy among nurses during COVID-19 pandemic: A large

cross-sectional study. J Clin Nurs. 2021 February 3. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15685

- Wang

H, Dai X, Yao Z, Zhu X, Jiang Y, Li J, Han B. The prevalence and risk

factors for depressive symptoms in frontline nurses under COVID-19

pandemic based on a large cross-sectional study using the propensity

score-matched method. BMC Psychiatry. 2021 March 16;21(1):152. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03143-z

- Kuzman

MR, Curkovic M, Wasserman D. Principles of mental health care during

the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Psychiatry. 2020 May 20;63(1):e45. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.54

- Adhanom

Ghebreyesus T. Addressing mental health needs: an integral part of

COVID-19 response. World Psychiatry. 2020 Jun;19(2):129-130. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20768

- McDaid

D. Viewpoint: Investing in strategies to support mental health recovery

from the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Psychiatry. 2021 Apr 26;64(1):e32. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.28

[TOP]