Ilaria Cozzi, Giovanni Rossi, Emma Rullo and Valeria Ascoli.

Department of Radiological, Oncological and Pathological Sciences, Sapienza University, Rome.

Correspondence to:

Valeria Ascoli - Dipartimento di Scienze Radiologiche, Oncologiche e

Anatomo-Patologiche, Università Sapienza, Viale Regina Elena, 324 -

00161, Roma. Tel: +39-06-49973397. E-mail:

valeria.ascoli@uniroma1.it

Published: March 1, 2022

Received: October 22, 2021

Accepted: February 8, 2022

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2022, 14(1): e2022020 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2022.020

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Primary

effusion lymphoma (PEL) is a large B-cell lymphoma growing within

body-cavities caused by the Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus

(KSHV)/human herpesvirus-8 (KSHV/HHV-8). It is mainly reported in

HIV-infected patients. The uncommon occurrence in the elderly supports

a form paralleling classic Kaposi sarcoma (KS), i.e. classic PEL, whose

characteristics are relatively underexplored. To better understand the

diagnostic modalities and clinical-epidemiological features of classic

PEL, articles reporting cases of PEL were identified through

MEDLINE/EMBASE databases (January 1998-July 2020) and screened

according to PRISMA guidelines to extract individual-level data. A

comparison was also performed between classic PEL and classic KS to

evaluate similarities and differences. We identified 105 subjects

(median age 77 years; 86% males), mainly from Mediterranean countries

(52%, first Italy) and Eastern Europe (7%). Common comorbidities were

heart failure (32%), cirrhosis (16%), and malignancy (20%) including

lymphoid neoplasms. Pleural cavity was the commonest site (67%). PEL

diagnosis was based on cytomorphology (89%), evidence of KSHV/HHV-8

infection (94%), EBV co-infection (28%) and clonality of IGH (59%), IGK

(14%), TRG (9%) alone or in multiple combinations. Compared to KS, age

(P<.001), gender-ratio (P=.08) and mortality (P<.001) were

significantly higher in PEL, whereas the frequency of PEL as a second

primary was similar (P=.44).

This is the first systematic review

of classic PEL case reports highlighting heterogeneity and lack of a

uniform multidisciplinary approach at diagnosis, in the absence of

specific guidelines as it happens for rare cancers. It is conceivable

that classic PEL is still underdiagnosed in Mediterranean countries

wherein KSHV/HHV-8 is endemic.

|

Introduction

Primary

effusion lymphoma (PEL) is a rare form of large B-cell lymphoma growing

in liquid phase within body cavities covered by the serous membranes

(pleura, pericardium, peritoneum), typically without solid tumor

lesions. PEL cells lack B-cell markers, present Ig gene rearrangements,

and a gene expression profile consistent with an

immunoblastic/plasmablastic derivation. The tumor clone is always

infected by the Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV)/human

herpesvirus-8 (KSHV/HHV-8, gamma-herpesvirus) and may be coinfected

with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). KSHV/HHV-8 was first detected in

AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma (KS)[1] and found

thereafter in the other forms of KS: sporadic/classic KS,

endemic/sub-Saharan African KS, and iatrogenic KS. KSHV/HHV-8 was then

discovered in AIDS-related body cavity-based lymphoma,[2] designated as a distinct clinicopathologic entity as PEL in 1996[3]

and then included in the WHO classification of neoplasms of the

hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues published in 2001 and updated in

2008 (ICD-O-3 code 9678/3).[4] As KS, PEL has

been described in HIV-infected individuals with severe immunodeficiency

(AIDS-related PEL) and HIV-uninfected patients such as solid organ

transplant recipients (iatrogenic PEL) and elderly patients from areas

with moderate/high prevalence for KSHV/HHV-8 infection. The latter

supports a distinct clinico-epidemiological form of PEL resembling

classic KS, i.e., classic PEL.[5,6] As of yet, cases of PEL outside HIV infection in Africa have not been formally reported.

Given

the rarity of KSHV/HHV-8-positive PEL, the epidemiology is poorly

defined. Available Cancer Registry data such as the SEER database in

the United States refer to PEL in the HIV-positive setting,[7]

as most published studies. PEL cases in the HIV-negative are mainly

presented as isolated case reports supplemented by nonsystematic

reviews of the literature, and more rarely in small case series.

However, no studies are investigating the diagnostic work-up flow or

providing specific strategies to reach a final diagnosis, considering

the challenge of a lymphoma growing in effusions outside the HIV

infection. In addition, data regarding the patient origin,

comorbidities associated with the clinical presentation, other primary

neoplasms, laboratory results have been scarce.

We have performed

a systematic review of the case reports of classic PEL to analyze all

the available data recorded in the literature. The aims include

providing insights into clinicopathological and epidemiological

features of classic PEL and determining the diagnostic modalities,

focusing on KSHV/HHV-8 status ascertainment and clonality analysis. For

the purpose of this study, we defined ‘classic PEL’ all the

KSHV/HHV-8-positive PEL outside HIV-infection that were also

non-iatrogenic and non-associated with primary immunodeficiency. To

better understand this form of PEL, we compared classic PEL with

classic KS, the most common and better studied HHV-8-associated

disease.[8]

Methods

Data sources and search strategy.

We carried out a computerized search of the Ovid MEDLINE (PubMed) and

EMBASE (Ovid) databases for potentially relevant studies in the English

language published from January 1995 to July 2020: full articles with

abstract, letters, and brief articles as images. Given the rarity of

the disease, we also considered congress abstract indexed in search

databases and non-English studies with at least an English abstract

providing sufficient information for inclusion. The electronic search

strategy was as follows: KSHV AND lymphoma* [title] or PEL [title];

KSHV AND PEL [title]; KSHV/HHV8 AND lymphoma* [title]; KSHV-positive

AND lymphoma*[title]; KSHV-associated AND lymphoma*[title]; Primary AND

Effusion AND lymphoma* [title]; Body AND Cavity AND lymphoma* [title];

KSHV/HHV-8-associated AND lymphoma* [title]; KSHV/HHV-8-related AND

lymphoma* [title]; Body AND cavity-based AND lymphoma*[title]; Primary

AND Effusion AND lymphoma* [title] or PEL [title](((lymphoma, primary

effusion[MeSH Terms]) OR (primary effusion lymphomas[MeSH Terms])) OR

(primary effusion lymphoma[MeSH Terms])) OR (lymphomas, primary

effusion[MeSH Terms]) OR (KSHV AND primary effusion lymphoma* [MeSH

Terms])).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The eligibility criteria were: i) primary localization of PEL in a

serous cavity covered by mesothelium (effusion-based disease without

solid nodal/extranodal tissue involvement); ii) morphologic features

and immunophenotype consistent with PEL; iii) demonstration of

KSHV/HHV-8 infection of the tumor clone. For inclusion, the published

cases must have documentation of diagnosis method(s) and individual

patient data. Criteria for exclusion were: i) negative/unrelated or

unknown KSHV/HHV-8 status; ii) HIV-infection; iii) solid organ

transplant or immunosuppressive therapy; iv) primary extracavitary

localization of PEL; v) primary immunodeficiency or idiopathic

lymphocytopenia. Further exclusion criteria were either non-relevant

titles or biomolecular and preclinical studies related to KSHV/HHV-8,

and narrative reviews. Case series that had their analysis pooled

without the description of individual patient data were also excluded.

Screening of literature.

The screening of eligible publications was carried out independently by

three reviewers (ER, GR and VA), first by screening titles and

abstracts and then reviewing the full text. All references meeting the

inclusion criteria, including those with scarce details, were

considered. Disagreements were resolved by consensus, and the final

decision was made by the author VA. In addition, IC undertook an

extensive updated literature search. All authors have contributed to

the data presentation and manuscript text. The whole review process was

performed according to PRISMA guidelines.[9]

Data extraction.

We extracted data on patient and PEL characteristics. Briefly, the

following aspects were considered: age, gender, country-of-origin, the

institution of diagnosis, comorbidities [Multicentric Castleman

Disease (MCD), KS, heart failure, cirrhosis and cause, other primary

cancers], laboratory data including blood count, LDH, markers of

inflammation, site of PEL, immunophenotype, immunoglobulins and T cell

receptor genes clonality evaluation, search for KSHV/HHV-8 and EBV

viral genomes, and outcomes.

Data synthesis and analysis.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize data, with median and

interquartile range for continuous variables and frequencies and

percentages for dichotomous variables. The nonparametric Wilcoxon

signed-rank test was used to compare the median, the t-test to compare

the mean and the Fisher’s exact test to determine nonrandom

associations between two categorical variables. Stata version 14.2

(StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). P <0.05 was considered

statistically significant.

Comparison between classic PEL and classic KS.

A PubMed search strategy including the terms Kapos*[Title] AND

classic*[Title] OR Mediterranean [Title] was carried out (January

1994-June 2020) to perform a comparison of the clinic-epidemiological

characteristics between classic PEL and classic KS. Since the classic

variant of KS is described as primarily occurring in individuals in

ethnic groups from Middle East, Eastern Europe, and the Mediterranean

regions,[8] the comparison was limited to classic PEL and classic KS

cases from these geographical areas. We decided arbitrarily to focus on

large case series/studies reporting at least 30 cases of classic KS who

have presented to referral centers for KS over a certain period, from

countries that in turn had reported cases of PEL. For inclusion, the

published cases must have had reviewers (VA, GR) screened all titles

and abstracts for eligibility.

Results

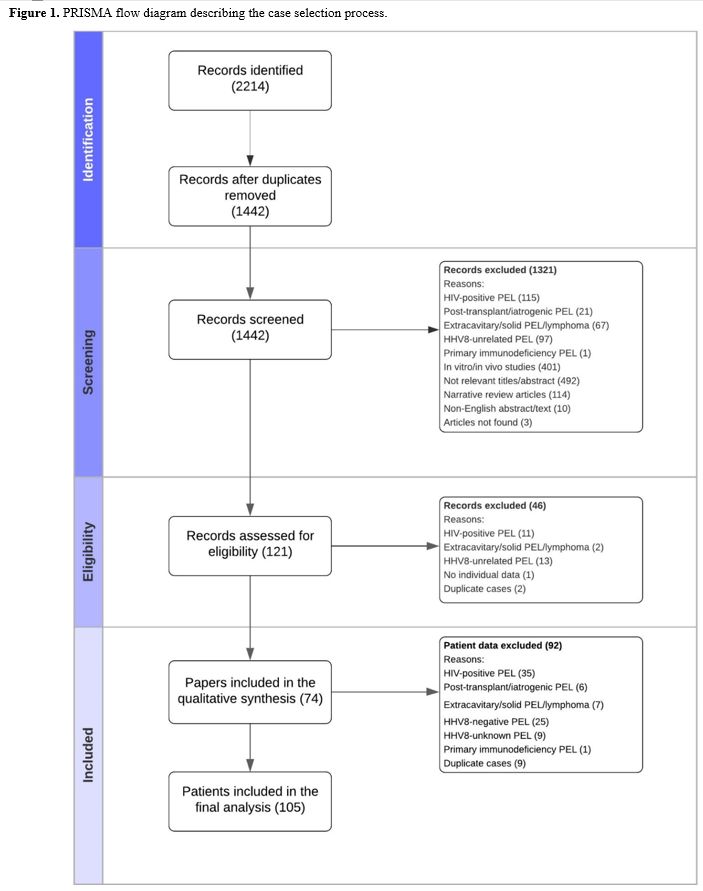

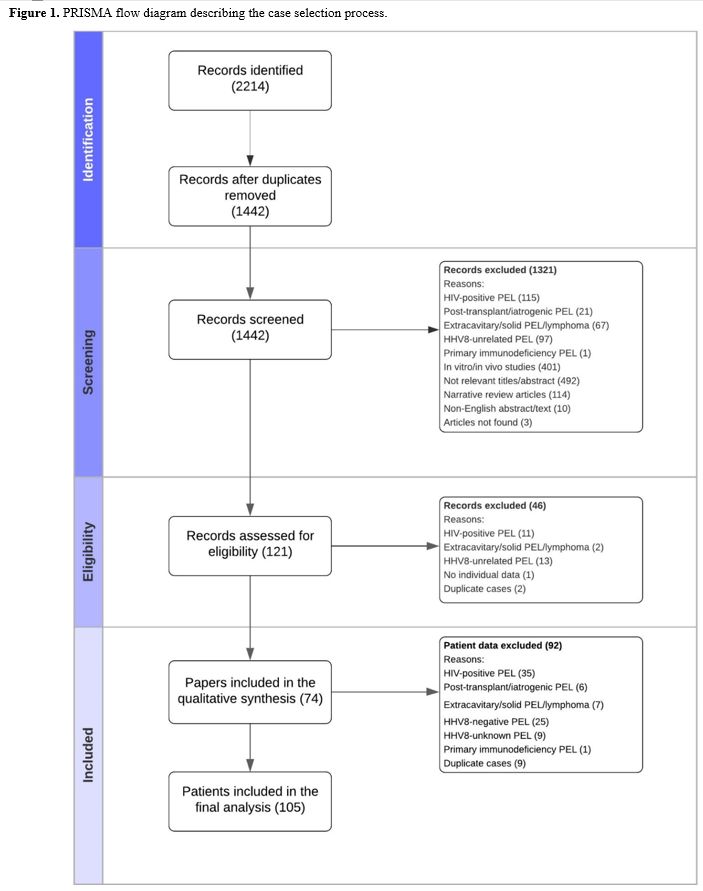

Selection and description of studies. The database searches identified 2214 studies (Figure 1).

After removing duplicate publications and papers that did not meet our

inclusion criteria, the remaining 121 studies were assessed for

eligibility. Forty-six studies were excluded following a more detailed

review. We included 74 studies in the final analysis, accounting for

105 individual patient cases. Over the 23-year period of publications,

32 studies were published during the first 12 years (1995-2008)[3,6,10-39] and 42 during the second 11 years (2009-2020)[40-81]

as full articles (n=58), letters (n=7), images (n=5), and conference

papers/abstracts (n=4). Sixty-eight (91.9%) articles reported one or

two cases.

|

Figure

1. PRISMA flow diagram describing the case selection process.

|

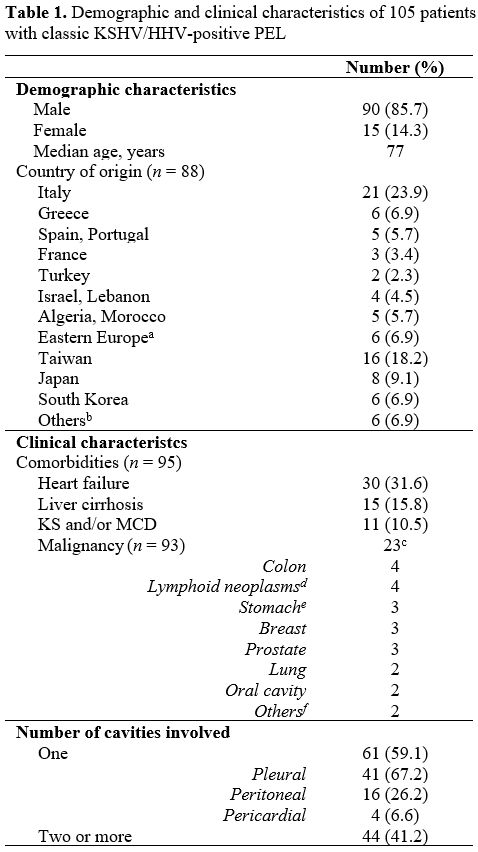

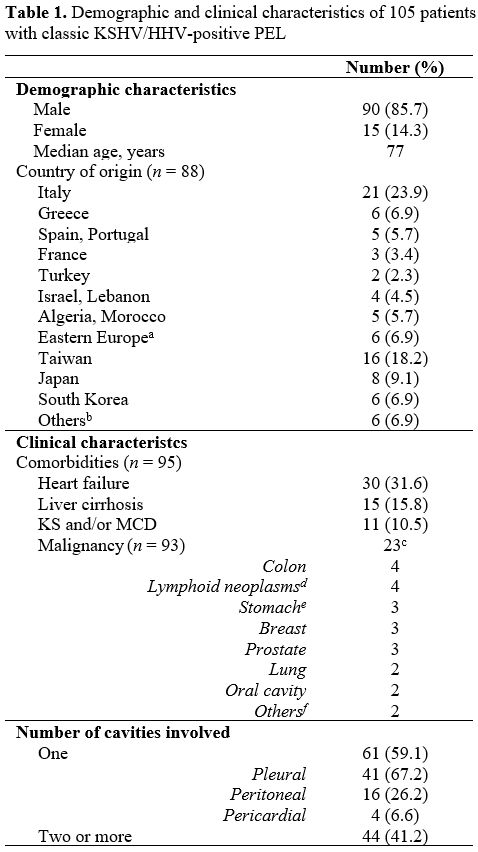

Patient demographics, comorbidities and PEL site. Demographics for 105 patients and clinical characteristics are listed in Table 1.

The median (interquartile range, IQR) age was 77 (69-85) with no gender

difference (P>.05). The male-to-female ratio was 6:1. The

country-of-origin was documented in 46 cases. For publications by

institutes and centers where this information was unreported (42

cases), we used the country affiliation of co-authors as a substitute

for patients' country-of-origin; however, this strategy did not apply

to 16 studies (17 cases) because of countries with a high rate of

immigration (USA, Canada, England). Combining reported and presumed

country-of-origin, the majority of cases were from the Mediterranean

basin (52.3%) and Eastern Europe (6.9%), followed by East Asia (35.2%).

The most represented countries were Italy (21 cases), Taiwan (16

cases), Japan (8 cases), South Korea (6 cases), and Greece (6 cases).

|

Table

1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of 105 patients with classic KSHV/HHV-positive PEL

|

The

clinical data were not consistently described. Of the underlying

conditions known in 95 patients (90.5%), heart failure was the most

common (31.5%); comparing patients with heart failure versus those

without, there was no difference in terms of age and sex (P>.05).

Fifteen patients (15.8%) had liver cirrhosis related to HBV and/or HCV

(n=9), alcohol (n=3), cryptogenic (n=3); the median age of cirrhotic

patients was significantly lower with respect to that of non-cirrhotic

patients (P<.001); there were also two HBV and two HCV mono-infected

patients without clinical evidence of cirrhosis. Overall, a history of

prior or concomitant malignancy was reported in 19/93 cases (20%), for

a total of 23 cancers. Three subjects had triple multiple primary

cancers. The co-occurrence of other KSHV/HHV-8-related neoplasms was

reported in 11 cases: KS (n=6), MCD (n=3), KS and MCD (n=2). Laboratory

parameters were described in a minority of the cases reviewed (49

patients, data not shown in Tables), of which 35 (71.4%) were reported

anemic, 3 (6.1%) leukopenic, and 14 (28.6%) as thrombocytopenic. The

median (IQR) hemoglobin count was 11 (9.4;12.4) in 36 patients whose

absolute value was reported. The CD4 count resulted below the normal

range in 10 out of 14 cases (71.4%), with a median (IQR) value of 241.5

(240;540). LDH and markers of inflammation (ESR and/or CRP) were

elevated in >70% of the patients tested (23/32 and 22/28,

respectively). Elevated serum beta2-microglobulin was found in 8 out of

9 patients tested.

Effusion in a single cavity was the most

commonly observed manifestation. Except for three cases involving both

the peritoneal and pericardial cavities, effusions in multiple sites

constantly involved the pleural cavity as either bilateral effusion

[pleural only (n=15), plus pericardial (n=5), plus peritoneal (n=3),

plus pericardial & peritoneal (n=3)] or unilateral effusion [plus

peritoneal (n=11), plus pericardial (n=4)]. The investigation of a

possible association between underlying pathologies and site of PEL

revealed statistically significant relationships between peritoneal

site and cirrhosis (P<.001) and bilateral pleural site and heart

failure (P<.001).

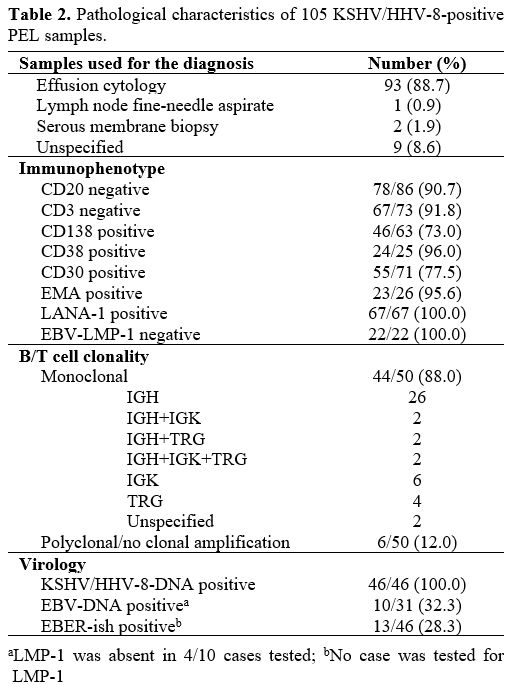

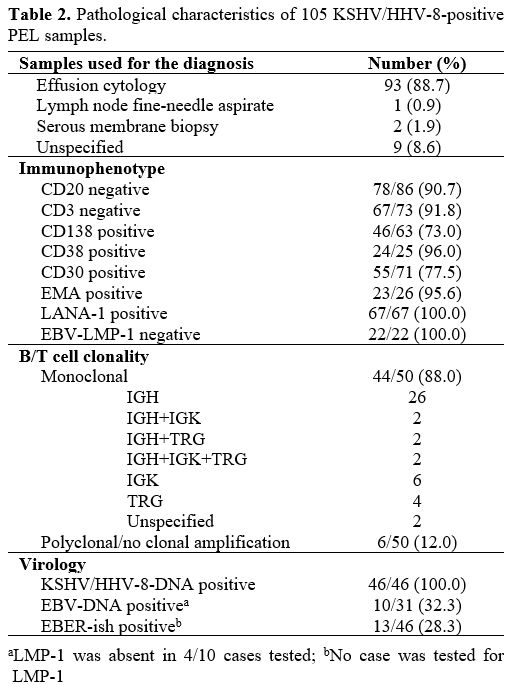

Methods of diagnosis, the sample of diagnosis, immunophenotype, virology, and clonality. Table 2

summarizes the integration of morphology with immunophenotype and

molecular techniques employed to diagnose PEL. Pathologic diagnosis was

performed primarily by cytology of effusions. The immunophenotype was

determined by flow cytometry (n=7) and immunohistochemistry (IHC) on

smears and/or cell blocks obtained from effusions (n=85) or other

specimens (n=4) for a total of 96 cases. The majority of the cases

lacked B/T cell antigens; yet, there were both CD3 positive (n=6) and

CD20 positive PELs (n=8). Details of morphology and immunophenotype

were not specified in 9 cases. The majority of the cases reviewed

(99/105; 94.3%) had proven KSHV/HHV-8 infection within PEL cells via

IHC and/or molecular analysis; expression of LANA-1 alone was the most

common approach (53/99; 53.5%), followed by DNA extraction and PCR

amplification of viral sequences alone (32/99; 32.3%), or through both

methods (14/99, 14.1%). Serum antibodies against KSHV/HHV-8[33,61] serum/effusion fluid[48] and lymph node KSHV/HHV-8 DNA[19] and unspecified method/sample[72]

were used as evidence of KSHV/HHV-8 etiologic involvement in a marginal

fraction of cases (6/105; 5.7%). Tumor EBER status (EBV coinfection)

was determined in 46/105 (43.8%) cases revealing mostly EBV-negative

tumors (71.7%).

|

Table 2. Pathological characteristics of 105 KSHV/HHV-8-positive PEL samples.

|

Clonality

investigation was performed in 50 cases (47.6%); yet, the technique of

clonality detection was unspecified for 5 and reported for 45 samples,

respectively: PCR (n=27), Southern blot (n=8), FISH (n=7),

immunonephelometry, Northern blot, and chromosomal aberrations study

(n=1 for each method). The tracking of antigen-receptor gene

rearrangements for clonality analysis was successful in 44 out of 50

cases. Most PELs harbored rearrangements of the IGH locus alone or in

multiple combinations with IGK and/or TRG and of the IGK locus alone,

identifying a B-cell lineage; some cases had rearrangement of TRG alone

(genotypic infidelity); the residual cases were reported as clonal

without any reference to a specific gene rearrangement. Some cases were

described as ‘polyclonal’ or ‘negative for clonal rearrangement of the

IGH genes’. Clonality was unavailable, not ascertained, or ‘failed’ in

the residual 55 cases (52.4%).

Finally, considering two periods in

comparison (1995-2009 vs. 2010-2020), the analysis of clonality and

proof of KSHV/HHV-8 infection based on the search of the viral genome

were reported more often in articles published during the first phase

(P=0.009 and P<.001, respectively). On the other hand, LANA

immunostaining was performed more frequently in the subsequent ten-year

interval (P<.001).

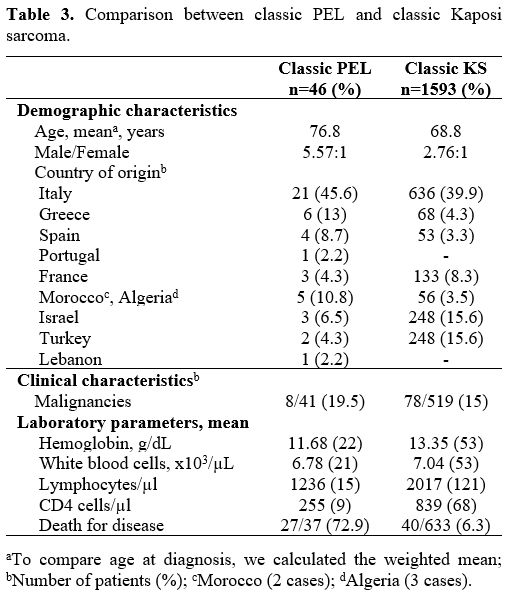

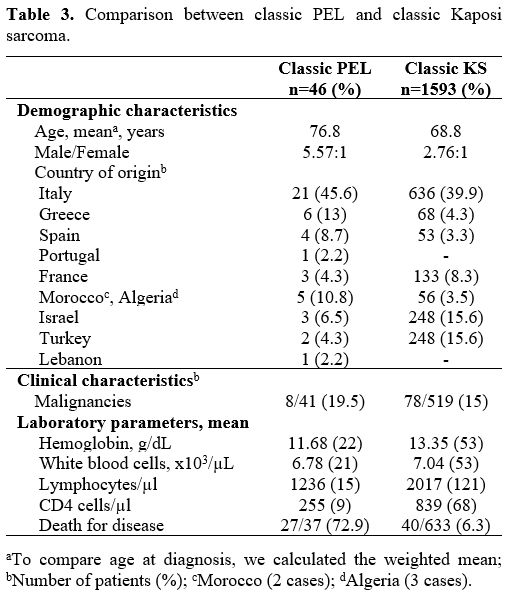

Comparison between classic PEL and classic KS.

The database search for classic KS identified 348 articles and a single

systematic review referring to the treatment of classic KS.[82]

Overall, 308 studies did not meet the inclusion criteria for the

following reasons: case reports or series less than 30 cases (n=208);

unavailable clinical/demographical data (n=24); narrative reviews

(n=6); data from non-Mediterranean areas (n=20); registry data (n=13);

non-English language studies (n=27); other studies (n=10). After

excluding articles with duplicate data (n=14) and lower-quality studies

with insufficient information (n=14), the remaining 12 publications

were used for the comparison.[83-94] Table 3

shows a concise comparison of demographics, clinical and laboratory

characteristics between classic variant of PEL and classic variant of

KS from countries of the Mediterranean regions, Middle East, and

eastern Europe. In the group of patients with PEL as compared to KS,

the mean age was significantly higher (P<.001), and the

male-to-female ratio was higher, though non-significant (P=.08). The

percentage of patients with malignancy was similar in the two cohorts

(P=.44). The number of deaths for the disease was significantly higher

in PEL (P<.001). Only 2 KS studies reported detailed laboratory

data;[93–94] compared to KS, PEL cases had

significantly lower hemoglobin level (P<.001), lymphocyte and CD4

counts (P<.001) while there was no significant difference in the

white blood cell counts (P=.08).

|

Table 3. Comparison between classic PEL and classic Kaposi sarcoma.

|

.

Discussion

There

was high heterogeneity in describing patient and PEL data across

different studies. We present here a systematic review of published

cases of classic PEL providing clinical and pathological insight into

rare disease, excluding cases developing in the HIV setting or any

immunosuppressive state (post-transplant, iatrogenic, and rare cases

associated with primitive immunodeficiencies).[79,95]

The review was undertaken and reported using the PRISMA guidelines,

including only cases of PEL caused by KSHV/HHV-8. The similar

epidemiological background shared by classic PEL and classic KS is why

we compared the two diseases.

One major finding is that a

significant proportion of the cases were observed in the elderly (more

men than women) over age 75 from Mediterranean countries (Italy first)

and Eastern Europe, and East Asia (Taiwan, Japan). Asia and Europe are

home to some of the world’s oldest populations (ages 65 and above). At

the top is Japan at 28 percent, followed by Italy at 23 percent.[96]

We

observed three recurring underlying conditions in comorbidity with

classic PEL: heart failure, cirrhosis, and malignancy. Bilateral

pleural effusions are commonly seen in patients with congestive heart

failure; ascites is the most common complication of liver cirrhosis.

Considering the great exchange of lymphocytes between pleural and

peritoneal cavities and secondary lymphoid organs, the presence of

cirrhosis and heart failure in PEL patients raises interest in the

potential pathogenetic role of associated effusions as an exogenous

stimulus for local clonal expansion of a subset of KSHV/HHV-8-infected

B-cells homing to body cavities.[97] It is

conceivable that these conditions play a role in the development of

PEL. Furthermore, patients with heart failure have an increased

significant risk of hematologic malignancies, with an incidence rate

ratio of 1.45 (95% CI 1.14–1.85, P=0.0027).[98] Liver

cirrhosis might be considered a condition with immunological

disturbances associated with a higher risk of developing

nodal/extranodal lymphoproliferative disorders, even as primary

effusion lymphoma in a body cavity.[99]

Interestingly, we found a statistical association between the bilateral

pleural site of PEL and congestive heart failure, and the peritoneal

site of PEL and cirrhosis. Regarding malignancy, the 20% frequency of

multiple primaries among PEL patients is slightly higher than expected

in literature (in the range of 2-17%).[100]

Interestingly, PEL patients aged >or= 70 years versus younger ones

have the same frequency of multiple primaries (19.1% vs. 20.5%,

respectively) at variance with the described higher prevalence in the

elderly compared with younger patients (15% vs. 6%).[101]

It is impossible to further comment on classic PEL and associated

malignancies for the small number of cancers and the lack and/or

incompleteness of oncological data in several articles. However, the

finding of prior Hodgkin’s lymphoma in three males (2 HCV-positive;

ages 43-44; 1 with colon cancer: age 68) is somewhat peculiar for the

rarity of this cancer. A further intriguing result is that of squamous

cell carcinomas of the oral cavity in two subjects (a man, age 69, from

Taiwan where the oral cancer incidence rate is the highest in the

world; a woman, age 77, from Italy with also breast cancer and

alcohol-related liver cirrhosis). We are no aware of data about the

risk of PEL secondary to a primary cancer; yet, a cancer registry study

has reported a significantly elevated risk of classic KS as a second

primary neoplasm following Hodgkin’s lymphoma with an odds ratio (OR)

of 7.5, chronic leukemia (OR=10), and breast cancer (OR=2.2) and a

non-significant risk after oral cavity malignancy (OR=1.9).[102]

In more than half of the PEL cases, no laboratory data were reported

thus preventing the description of shared clinical features, with the

exception of anemia (low hemoglobin), decreased immunity (low CD4

count) together with low-grade chronic inflammation (elevated markers

of inflammation) in the few patients who were tested; the latter can be

referred to as inflammaging,[103] which contributes to the pathogenesis of age-related PEL.

In

the current review, heterogeneity emerges in the diagnostic process of

PEL. Cytological examination of effusions and identification of

KSHV/HHV-8 infection in tumor cells by LANA positive immunostaining

and/or by molecular search of KSHV/HHV-8 genome contributed to the

diagnosis in 100% of instances where the testing was performed.

However, sporadic cases were diagnosed by histology of the serosal

membranes rather than by cytology of the intracavitary fluid,[77] with proof of KSHV/HHV-8 involvement by finding viral genome in extra-cavitary tissue samples[19] or by serology testing.[33,48,61]

The presence of KSHV/HHV-8 in lymphoma cells should be considered an

absolute requirement for diagnosing KSHV/HHV-8-associated PEL, whereas

the detection of serum antibodies against KSHV/HHV-8 is only a marker

of infection, not of disease.

Genetics of PEL typically include

finding clonal rearrangements of IG genes or, more rarely, of T-cell

receptor genes. Indeed, most reported cases of PEL harbor

rearrangements of the IGH locus alone or in multiple combinations with

IGK and/or TRG, but also of the IGK locus alone (identifying a B-cell

lineage); some cases had rearrangement of TRG alone (genotypic

infidelity). Nevertheless, clonality is not being systematically

investigated in PEL (50 cases, 47.61%), and six cases resulted

polyclonal (n=2) or ‘negative for clonal rearrangement of the IGH

genes’ (n=4), all of them tested only for IGH locus by PCR. Therefore,

considering the heterogeneity of rearrangements, the best way to

ascertain clonality in PEL would be to investigate IGH and IGK and TCR.

Failure to demonstrate clonality could be ascribed to: (i) impaired

primers annealing; (ii) genetic alterations involving the IG loci;

(iii) lack to investigation of IGK locus or TRG rearrangements. A

polyclonal pattern may be the expression of an effusion that mimics PEL

described as pseudo-PEL;[104] alternatively, it may suggest the possibility of polyclonal PEL or emerging PEL.[105]

The question of why clonality assessments are not available in many

cases (>50%) is not commented on by different authors, and

regrettably, these rare PELs have not been better analyzed. Clonality

testing represents a qualitative improvement to characterize

lymphoproliferative diseases and clarify the lineage of a

null-phenotype lymphoma such as PEL.

Although the epidemic

(HIV-related) and iatrogenic (post-transplant) variants of PEL easily

find a match regarding KS in these settings, less known is the

comparison between classic PEL in the elderly and classic KS for the

lack of ad hoc studies. The comparison between the two diseases was not

straightforward. We considered only 12 studies out of more than three

hundred, to collect fragmentary data; excluded articles focused on the

pathogenesis and the molecular landscape of KS, and therapeutic

options. Nevertheless, we attempted to build up a control group of KS

patients to compare it with classic PEL patients. It must be pointed

out that this comparison has limits linked to the difference in the

size of the two groups, that may affect the statistical power. Our

comparison indicates remarkable similarities between PEL and KS in the

elderly population, supporting a clinical variant of PEL paralleling

classic KS but has put in light some differences. In classic-PEL there

is a slightly higher male prevalence, and patients are significantly

older. Other important differences are found comparing the laboratory

data: PEL patients have lower lymphocytes count, CD4 count, and

hemoglobin levels. Classic PEL is far more lethal compared to classic

KS. These divergent aspects raise up some questions: (i) if the classic

variants of PEL and KS have a distinct biologic behavior (very

aggressive, PEL; indolent, KS) that would explain the clinical and

laboratory differences or (ii) if these diseases provoke a different

outcome because occurring in two different groups of hosts. Many

preclinical studies support the first hypothesis. KS spindle cells do

not behave like typical cancer cells; they do not form tumors in nude

mice, and the majority of KS tumors are polyclonal; all KS

tumor-derived cells to date have lost viral genomes upon ex vivo

cultivation. By contrast, PEL cell lines exhibit monoclonality, easily

grow when implanted in nude mice and maintain KSHV/HHV-8 indefinitely.

A few clinical observations support the second hypothesis: the host

status may influence the different clinical course between classic KS

and classic PEL. PEL patients are older than KS patients; their

cellular immunity decrease because of the immunosenescence process that

leads to reduced lymphocytes and CD4 counts, thus favouring KSHV/HHV-8

virulence, PEL cells survival, and worse prognosis and lethality. To

note, a minority of very elderly PEL patients (median age=85) had

concomitant KS in advanced stages with progressive disease.

Nevertheless, the finding of indolent cases of classic PEL and

aggressive and lethal classic KS cases may also be related to the host.

Finally, the worse prognosis of PEL patients may be explained because

this lymphoma is hidden in a body cavity effusion, differently from KS

lesions that arise on the skin and can be detected in their very early

phases.

The present review carries inherent limits associated with

the quality and completeness of the published studies. Considering the

rare occurrence of PEL outside immunodeficiency settings, we preferred

to include rather than exclude all available cases reported as

abstracts, short reports, images, in addition to full articles. Another

controversial issue might be the a priori

exclusion of extracavitary PEL cases. KSHV/HHV-8 has been associated

with a wide and heterogeneous group of lymphoproliferative processes

including liquid-based PEL and tissue-based extracavitary/solid

lymphomas with significant clinicopathological overlap.[106]

Although extracavitary/solid HHV8-positive lymphoma can precede or

follow a typical case of cavity effusion-based PEL, our study aimed

indeed to focus on the effusion-only PEL subgroup. This choice was

based on our case-series study on PEL with effusion-only disease in the

elderly, in the HIV-negative context.[79] Remarkably,

a recent multi-institutional case-series study has reported that 7 out

of 8 HIV-negative PEL patients (median age >75 years) had

effusion-only disease; by contrast, patients with extracavitary PEL

were younger and more likely HIV-positive.[107] The

comparison between classic PEL and classic KS was hampered by the lack

of uniformity in KS studies that often report aggregated data rather

than highlighting individual patient’s profile, so data availability

bias is a potential concern of our analysis. A higher power study with

more cases is warranted to further investigate the differences between

classic PEL and classic KS.

Conclusions

Our

study is the first systematic review of the literature focusing on

classic PEL, a clinicopathological variant of KSHV/HHV-8-related

effusion-only PEL probably underrecognized in the elderly population of

KSHV/HHV-8 endemic areas.

Acknowledgments

This study is dedicated to the memory of Francesco Lo Coco, Professor of Hematology (1955-2019).

References

- Chang Y, Cesarman E, Pessin MS, Lee F, Culpepper J,

Knowles DM, Moore PS. Identification of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences

in AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. Science. 1994;266: 1865–1869. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.7997879

- Cesarman

E, Chang Y, Moore PS, Said JW, Knowles DM. Kaposi’s Sarcoma–Associated

Herpesvirus-Like DNA Sequences in AIDS-Related Body-Cavity–Based

Lymphomas. New England Journal of Medicine. 1995;332: 1186–1191. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199505043321802

- Nador

RG, Cesarman E, Chadburn A, Dawson DB, Ansari MQ, Said J, Knowles DM.

Primary Effusion Lymphoma: A Distinct Clinicopathologic Entity

Associated With the Kaposi’s Sarcoma-Associated Herpes Virus. Blood.

1996;88(2):645-6. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.V88.2.645.bloodjournal882645

- Said

J, Cesarman E. Primary effusion lymphoma. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E,

Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, Thiele J, eds. WHO

Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. 4th

ed. IARC Press; 2017:323-324

- Calabrò ML,

Sarid R. Human herpesvirus 8 and lymphoproliferative disorders.

Mediterranean Journal of Hematology and Infectious Diseases.

2018;10(1). https://doi.org/10.4084/mjhid.2018.061

- Ascoli

V, lo Coco F, Torelli G, Vallisa D, Cavanna L, Bergonzi C, et al. Human

herpesvirus 8-associated primary effusion lymphoma in human

immunodeficiency virus-negative patients: A clinico-epidemiologic

variant resembling classic Kaposi’s sarcoma. Haematologica.

2002;87:339–43. https://moh-it.pure.elsevier.com/en/publications/human-herpesvirus-8-associated-primary-effusion-lymphoma-in-human

- Khoury

J, Willner CA, Gbadamosi B, Gaikazian S, Jaiyesimi I. Demographics and

Survival in Primary Effusion Lymphoma: SEER Database Analysis. Blood.

2018;132: 5397–5397. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2018-99-115473

- Cesarman E, Damania B, Krown SE, Martin J, Bower M, Whitby D. Kaposi sarcoma. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2019;5. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-019-0060-9

- Stewart

LA, Clarke M, Rovers M, Riley RD, Simmonds M, Stewart G, Tierney JF.

Preferred reporting items for a systematic review and meta-analysis of

individual participant data: The PRISMA-IPD statement. JAMA - Journal

of the American Medical Association. 2015; 313: 1657–1665. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.3656

- Nador

RG, Cesarman E, Knowles DM, Said JW. Herpes-Like DNA Sequences in a

Body-Cavity–Based Lymphoma in an HIV-Negative Patient. New England

Journal of Medicine. 1995;333: 943–943. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM199510053331417

- Strauchen

JA, Hauser AD, Burstein D, Jimenez R, Moore PS, Chang Y. Body Cavity -

Based Malignant Lymphoma Containing Kaposi Sarcoma - Associated

Herpesvirus in an HIV-Negative Man with Previous Kaposi Sarcoma. Annals

of Internal Medicine. 1996;125: 822–825. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-125-10-199611150-00006

- Carbone

A, Gloghini A, Vaccher E, Zagonel V, Pastore C, Palma PD, Branz F,

Saglio G, Volpe R, Tirelli U, Gaidano G. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated

herpesvirus DNA sequences in AIDS-related and AIDS-unrelated

lymphomatous effusions. British Journal of Haematology.

1996;94(3):533-43. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2141.1996.d01-1826.x

- Said

JW, Tasaka T, Takeuchi S, Asou H, de Vos S, Cesarman E, Knowles DM,

Koeffler HP. Primary effusion lymphoma in women: Report of two cases of

Kaposi’s sarcoma herpes virus-associated effusion-based lymphoma in

human immunodeficiency virus-negative women. Blood. 1996;88: 3124–3128.

https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.v88.8.3124.bloodjournal8883124

- Okada

T, Katano H, Tsutsumi H, Kumakawa T, Sawabe M, Arai T, et al.

Body-cavity-based lymphoma in an elderly AIDS-unrelated male.

International Journal of Hematology. 1998;67:417-422. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0925-5710(98)00014-0

- Teruya-Feldstein

J, Zauber P, Setsuda JE, Berman EL, Sorbara L, Raffeld M, Tosato G,

Jaffe ES. Expression of human herpesvirus-8 oncogene and cytokine

homologues in an HIV-seronegative patient with multicentric Castleman's

disease and primary effusion lymphoma. Lab Invest. 1998

Dec;78(12):1637-42. Erratum in: Lab Invest 1999;79(7):835.

- Vu

HN, Jenkins FW, Swerdlow SH, Locker J, Lotze MT. Pleural effusion as

the presentation for primary effusion lymphoma. Surgery. 1998;123:

589–591. https://doi.org/10.1067/msy.1998.88087

- Ascoli

V, Scalzo CC, Danese C, Vacca K, Pistilli A, lo Coco F. Human herpes

virus-8 associated primary effusion lymphoma of the pleural cavity in

HIV-negative elderly men. Eur Respir J. 1999 Nov;14:1231-1234. https://erj.ersjournals.com/content/14/5/1231

- San

Miguel P, Manzanal A, García González R, Bellas C. Association of body

cavity-based lymphoma and human herpesvirus 8 in an HIV-seronegative

male: Report of a case with immunocytochemical and molecular studies.

Acta Cytologica. 1999;43: 299–302. https://doi.org/10.1159/000330998

- Ariad

S, Benharroch D, Lupu L, Davidovici B, Dupin N, Boshoff C. Early

peripheral lymph node involvement of human herpesvirus 8- associated,

body cavity-based lymphoma in a human immunodeficiency virus- negative

patient. Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. 2000;124:

753–755. https://doi.org/10.5858/2000-124-0753-eplnio

- Codish

S, Abu-Shakra M, Ariad S, Zirkin HJ, Yermiyahu T, Dupin N, Boshoff C,

Sukenik S. Manifestations of three KSHV/HHV-8-related diseases in an

HIV-negative patient: Immunoblastic variant multicentric Castleman’s

disease, primary effusion lymphoma, and Kaposi’s sarcoma. American

Journal of Hematology. 2000;65: 310–314. https://doi.org/10.1002/1096-8652(200012)65:4<310::AID-AJH11>3.0.CO;2-G

- Polskj

JM, Evans HL, Grosso LE, Popovic WJ, Taylor L, Dunphy CH. CD7 and

CD56-Positive Primary Effusion Lymphoma in a Human Immunodeficiency

Virus-Negative Host. Leukemia and Lymphoma. 2000;39: 633–639. https://doi.org/10.3109/10428190009113394

- Lechapt-Zalcman

E, Challine D, Ne Delfau-Larue M-H, Haioun C, Desvaux D, Gaulard P.

Association of Primary Pleural Effusion Lymphoma of T-Cell Origin and

Human Herpesvirus 8 in a Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Seronegative Man.

Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001. https://doi.org/10.5858/2001-125-1246-AOPPEL

- Pérez

CL, Rudoy S. Anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody treatment of human

herpesvirus 8-associated, body cavity-based lymphoma with an unusual

phenotype in a human immunodeficiency virus-negative patient. Clinical

and Diagnostic Laboratory Immunology. 2001;8: 993–996. https://:10.1128/CDLI.8.5.993-996.2001

- Klepfish

A, Sarid R, Shtalrid M, Shvidel L, Berrebi A, Schattner A. Primary

effusion lymphoma (PEL) in HIV-negative patients - A distinct clinical

entity. Leukemia and Lymphoma. 2001;41: 439–443. https://doi.org/10.3109/10428190109058002

- Boulanger

E, Hermine O, Fermand JP, Radford-Weiss I, Brousse N, Meignin V,

Gessain A. Human Herpesvirus 8 (KSHV/HHV-8)-Associated Peritoneal

Primary Effusion Lymphoma (PEL) in Two HIV-Negative Elderly Patients.

American Journal of Hematology. 2004;76: 88–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.20048

- Munichor

M, Cohen H, Sarid R, Manov I, Iancu TC. Human herpesvirus 8 in primary

effusion lymphoma in an HIV-seronegative male: A case report. Acta

Cytologica. 2004;48: 425–430. https://doi.org/10.1159/000326398

- Luppi

M, Trovato R, Barozzi P, Vallisa D, Rossi G, Re A, Ravazzini L, Potenza

L, Riva G, Morselli M, Longo G, Cavanna L, Roncaglia R, Torelli G.

Treatment of herpesvirus associated primary effusion lymphoma with

intracavity cidofovir. Leukemia. Nature Publishing Group; 2005. pp.

473–476. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.leu.2403646

- Halfdanarson

TR, Markovic SN, Kalokhe U, Luppi M. A non-chemotherapy treatment of a

primary effusion lymphoma: Durable remission after intracavitary

cidofovir in HIV negative PEL refractory to chemotherapy. Annals of

Oncology. 2006;17:1849–1850. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdl139

- Won

JH, Han SH, Bae SB, Kim CK, Lee NS, Lee KT, Park SK, Hong DS, Lee DW,

Park HS. Successful eradication of relapsed primary effusion lymphoma

with high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation in

a patient seronegative for human immunodeficiency virus. International

Journal of Hematology. 2006;83: 328–330. https://doi.org/10.1532/IJH97.A30510

- Hsieh

PY, Huang SI, Li DK, Mao TL, Sheu JC, Chen CH. Primary effusion

lymphoma involving both pleural and abdominal cavities in a patient

with hepatitis B virus-related liver cirrhosis. Journal of the Formosan

Medical Association. 2007;106: 504–508. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60302-8

- Siddiqi

T, Joyce RM. A case of HIV-negative primary effusion lymphoma treated

with bortezomib, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, and rituximab.

Clinical Lymphoma and Myeloma. 2008;8: 300–304. https://doi.org/10.3816/CLM.2008.n.042

- Cobo

F, Hernández S, Hernández L, Pinyol M, Bosch F, Esteve J,

López-Guillermo A, Palacín A, Raffeld M, Montserrat E, Jaffe ES, Campo

E. Expression of potentially oncogenic KSHV/HHV-8 genes in an

EBV-negative primary effusion lymphoma occurring in an HIV-seronegative

patient. Journal of Pathology. 1999;189: 288–293. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199910)189:2<288::AID-PATH419>3.0.CO;2-F

- Niitsu

N, Chizuka A, Sasaki K, Umeda M. Human herpes virus-8 associated with

two eases of primary-effusion lymphoma. Annals of Hematology. 2000;79:

336–339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002779900145

- Buonaiuto

D, Rossi D, Guidetti F, Vivenza D, Berra E, Deambrogi C, Ariatti C,

Franceschetti S, Conconi A, Ronco M, Valente G, Colombi S. Human

herpesvirus type 8-associated primary lymphomatous effusion in an

elderly HIV-negative patient: clinical and molecular characterization.

Annali italiani di medicina interna: organo ufficiale della Società Italiana di Medicina Interna. 2002;17: 54–59.

- Wakely

PE, Menezes G, Nuovo GJ. Primary Effusion Lymphoma: Cytopathologic

Diagnosis Using In Situ Molecular Genetic Analysis for Human

Herpesvirus 8. Modern Pathology. 2002;15: 944–950. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880635

- Metaxa-Mariatou

V, Papaioannou D, Loli A, Papadopoulou I, Gazouli M, Mavroudis P,

Nasioulas G. Subtype C1 persistent infection of KSHV/HHV-8 in a PEL

patient. Leukemia and Lymphoma. 2005;46: 1507–1512. https://doi.org/10.1080/10428190500161965

- Shirokov

D, Kadyrova E, Anokhina M, Kondratyeva T, Gourtsevich V, Tupitsyn N. A

case of KSHV/HHV-8-associated HIV-negative primary effusion lymphoma in

moscow. Journal of Medical Virology. 2007;79: 270–277.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.20795

- Dargent

JL, Kains JP, Verhest A. Primary effusion lymphoma presenting as

Richter’s syndrome [1]. Cytopathology. 2007. pp. 319–321. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2303.2007.00465.x

- Su

YC, Chai CY, Chuang SS, Liao YL, Kang WY. Cytologic diagnosis of

primary effusion lymphoma in an HIV-negative patient. Kaohsiung Journal

of Medical Sciences. 2008;24: 548–552. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70015-4

- Brimo F, Popradi G, Michel R, Auger M. Primary effusion lymphoma involving three body cavities. CytoJournal. 2009;6. https://doi.org/10.4103/1742-6413.56361

- de

Filippi R, Iaccarino G, Frigeri F, di Francia R, Crisci S, Capobianco

G, Arcamone M, Becchimanzi C, Amoroso B, de Chiara A, Corazzelli G,

Pinto A. Elevation of clonal serum free light chains in patients with

HIV-negative primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) and PEL-like lymphoma.

British Journal of Haematology. 2009. pp. 405–408. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07846.x

- Wu

SJ, Hung CC, Chen CH, Tien HF. Primary effusion lymphoma in three

patients with chronic hepatitis B infection. Journal of Clinical

Virology. 2009;44: 81–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2008.08.015

- Kishimoto

K, Kitamura T, Hirayama Y, Tate G, Mitsuya T. Cytologic and

immunocytochemical features of EBV negative primary effusion lymphoma:

Report on seven Japanese cases. Diagnostic Cytopathology. 2009;37:

293–298. https://doi.org/10.1002/dc.21022

- Honda

M, Morikawa T, Yamaguchi Y, Tani M, Yamaguchi K, Iijima K, et al. A

case of a primary effusion lymphoma in the elderly. Japanese Journal of

Geriatrics. 2009;46: 551–556. https://doi.org/10.3143/geriatrics.46.551

- Wang

HY, Fuda FS, Chen W, Karandikar NJ. Notch1 in primary effusion

lymphoma: A clinicopathological study. Modern Pathology. 2010;23:

773–780. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2010.67

- Makis

W, Stern J. Hepatitis C-related primary effusion lymphoma of the pleura

and peritoneum, imaged with F-18 FDG PET/CT. Clinical Nuclear Medicine.

2010;35: 797–799. https://doi.org/10.1097/RLU.0b013e3181ef09b1

- Stingaciu

S, Ticchioni M, Sudaka I, Haudebourg J, Mounier N. Intracavitary

cidofovir for human herpes virus-8-associated primary effusion lymphoma

in an HIV-negative patient. Clinical Advances in Hematology and

Oncology. 2010;8: 367–372.

- Yiakoumis

X, Pangalis GA, Kyrtsonis MC, Vassilakopoulos TP, Kontopidou FN,

Kalpadakis C, et al. Primary effusion lymphoma in two HIV-negative

patients successfully treated with pleurodesis as first-line therapy.

Anticancer Research. 2010;30: 271–276. https://ar.iiarjournals.org/content/30/1/271/tab-article-info

- Gandhi

SA, Mufti G, Devereux S, Ireland R. Primary effusion lymphoma in an

HIV-negative man. British Journal of Haematology. 2011;155:411. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08778.x

- Ganzel

C, Rowe JM, Ruchlemer R. Primary effusion lymphoma in a HIV-negative

patient associated with hypogammaglobulinemia. American Journal of

Hematology. 2011;86:777–781. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.22068

- Kumar

T, Rosen M, Breuer F. Primary Effusion Lymphoma Involving Pleural and

Peritoneal Cavities in An HIV Negative Patient.

2011.183.1_meetingabstracts.a2953. https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm-conference

- Nakayama-Ichiyama

S, Yokote T, Kobayashi K, Hirata Y, Hiraoka N, Iwaki K, Takayama A,

Akioka T, Oka S, Miyoshi T, Fukui H, Tsuda Y, Takubo T, Tsuji M,

Higuchi K, Hanafusa T. Primary effusion lymphoma of T-cell origin with

t(7;8)(q32;q13) in an HIV-negative patient with HCV-related liver

cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma positive for HHV6 and

KSHV/HHV-8. Annals of Hematology. 2011;90:1229–1231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-011-1165-8

- Zacharis

E, Ntoula E, Sevastiadou M, Fragkopoulos C, Gklisti E, Alexiadou A,

Plyta S, Panousi A. Paramount role of ancillary techniques in

diagnosing a rare incident of primary effusion lymphoma by fine needle

aspiration cytology. Cytopathology. 2011;22(s1):150. Available: https://www.embase.com/search/results?subaction=viewrecord&id=L70678203&from=export%0Ahttp://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2303.2011.00911.x

- Kabiawu-Ajise

OE, Harris J, Ismaili N, Amorosi E, Ibrahim S. Primary effusion

lymphoma with central nervous system involvement in an HIV-negative

homosexual male. Acta Haematologica. 2012;128: 77–82. https://doi.org/10.1159/000338183

- Lobo

C, Amin S, Ramsay A, Diss T, Kocjan G. Serous fluid cytology of

multicentric Castleman’s disease and other lymphoproliferative

disorders associated with Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpes virus: A

review with case reports. Cytopathology. 2012;55: 76–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2303.2011.00868.x

- Nepka

C, Kanakis D, Samara M, Kapsoritakis A, Potamianos S, Karantana M, et

al. An unusual case of Primary Effusion Lymphoma with aberrant T-cell

phenotype in a HIV-negative, HBV-positive, cirrhotic patient, and

review of the literature. CytoJournal. 2012;9:16. https://doi.org/10.4103/1742-6413.97766

- Karataş

SG, Bayrak R, Balçk ÖŞ, Yalçn KS, Atici E, Akyildiz Ü, Koşar A. Human

Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)-Negative and Human Herpes Virus-8

(KSHV/HHV-8)-Positive Primary Effusion Lymphoma: A Case Report and

Review of the Literature. Turkish Journal of Hematology. 2013;30:

67–71. https://doi.org/10.4274/tjh.53215

- Kumode

T, Ohyama Y, Kawauchi M, Yamaguchi T, Miyatake JI, Hoshida Y, Tatsumi

Y, Matsumura I, Maeda Y. Clinical importance of human herpes virus-8

and human immunodeficiency virus infection in primary effusion

lymphoma. Leukemia and Lymphoma. 2013;54: 1947–1952. https://doi.org/10.3109/10428194.2012.763122

- Ozbalak

M, Tokatli I, Özdemirli M, Tecimer T, Ar MC, Örnek S, et al. Is

valganciclovir really effective in primary effusion lymphoma: Case

report of an HIV(-) EBV(-) KSHV/HHV-8(+) patient. European Journal of

Haematology. 2013;91: 467–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejh.12174

- Song JY, Jaffe ES. KSHV/HHV-8-Positive but EBV-Negative primary effusion lymphoma. Blood. 2013. 3712. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-07-515882

- Antar

A, Hajj H el, Jabbour M, Khalifeh I, EL-Merhi F, Mahfouz R, et al.

Primary effusion lymphoma in an elderly patient effectively treated by

lenalidomide: Case report and review of literature. Blood Cancer

Journal. 2014;4:e190. https://doi.org/10.1038/bcj.2014.6

- Sasaki

Y, Isegawa T, Shimabukuro A, Yonaha T, Yonaha H. Primary Effusion

Lymphoma in an Elderly HIV-Negative Patient with Hemodialysis:

Importance of Evaluation for Pleural Effusion in Patients Receiving

Hemodialysis. Case Reports in Nephrology and Urology. 2014;4: 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1159/000363223

- Wang

HY, Thorson JA. T-cell primary effusion lymphoma with pseudo-monoclonal

rearrangements for immunoglobulin heavy chain. Blood. American Society

of Hematology. 2015;126: 1856. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2015-06-648923

- Klepfish

A, Zuckermann B, Schattner A. Primary effusion lymphoma in the absence

of HIV infection-clinical presentation and management. QJM. 2015;108:

481–488. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcu232

- Nicola

M, Onorati M, Bianchi CL, Pepe G, Bellone S, di Nuovo F. Primary

Effusion Lymphoma: Cytological Diagnosis of a Rare Entity-Report of Two

Cases in HIV-Uninfected Patients from a Single Institution. Acta

Cytologica. 2015;59: 425–428. https://doi.org/10.1159/000441938

- Birsen

R, Boutboul D, Crestani B, Seguin-Givelet A, Fieschi C, Bertinchamp R,

Giol M, Malphettes M, Oksenhendler E, Galicier L. Talc pleurodesis

allows long-term remission in HIV-unrelated Human Herpesvirus

8-associated primary effusion lymphoma. Leukemia and Lymphoma.

2017;58:1993-1998. https://doi.org/10.1080/10428194.2016.1271947

- Gonzalez-Farre

B, Martinez D, Lopez-Guerra M, Xipell M, Monclus E, Rovira J, Garcia F,

Lopez-Guillermo A, Colomo L, Campo E, Martinez A. HHV8-related lymphoid

proliferations: A broad spectrum of lesions from reactive lymphoid

hyperplasia to overt lymphoma. Modern Pathology. 2017;30: 745–760. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2016.233

- Chan

TSY, Mak V, Kwong YL. Complete radiologic and molecular response of

HIV-negative primary effusion lymphoma with short-course lenalidomide.

Annals of Hematology. 2017;96: 1211–1213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-017-2995-9

- Yamani

F, Chen W. Cytokeratin-positive primary effusion lymphoma: a diagnostic

challenge. British Journal of Haematology. 2018;180: 9. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.14904

- Galán

J, Martin I, Carmona I, Rodriguez-Barbero JM, Cuadrado E, García-Alonso

L, García-Vela JA. The utility of multiparametric flow cytometry in the

detection of primary effusion lymphoma (PEL). Cytometry Part B -

Clinical Cytometry. 2019;96: 375–378. https://doi.org/10.1002/cyto.b.21637

- Li

Y, Henn P, Zhang Y, Sands A, Zhang N. 160 Case Report: Primary Effusion

Lymphoma in an 88-Year-Old Man. American Journal of Clinical Pathology.

2018;149: S68–S69. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcp/aqx121.159

- Mirza

AS, Dholaria BR, Hussaini M, Mushtaq S, Horna P, Ravindran A, Kumar A,

Ayala E, Kharfan-Dabaja MA, Bello C, Chavez JC, Sokol L. High-dose

Therapy and Autologous Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation as

Consolidation Treatment for Primary Effusion Lymphoma. Clinical

Lymphoma, Myeloma and Leukemia. 2019;19: e513–e520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clml.2019.03.021

- Shin

J, Ko YH, Oh SY, Yoon DH, Lee JO, Kim JS, Park Y, Shin HJ, Kim SJ, Won

JH, Yoon SS, Kim WS, Koh Y. Body Cavity-Based Lymphoma in a Country

with Low Human Immunodeficiency Virus Prevalence: A Series of 17 Cases

from the Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma. Cancer Research

and Treatment. 2019;51:1302–12. https://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2018.555

- Aguilar

C, Laberiano C, Beltran B, Diaz C, Taype-Rondan A, Castillo JJ.

Clinicopathologic characteristics and survival of patients with primary

effusion lymphoma. Leukemia and Lymphoma. 2020;61: 2093–2102. https://doi.org/10.1080/10428194.2020.1762881

- Kropf

J, Gerges M, Perez AP, Ellis A, Mathew M, Ayesu K, Ge L, Carlan SJ. T

Cell Primary Effusion Lymphoma in an HIV-Negative Man with Liver

Cirrhosis. Am J Case Rep. 2020;21:e919032. https://doi.org/10.12659/AJCR.919032

- Kuo

HI, Yu YT, Chang KC, Su PL, Li SS, Huang TH. Human herpesvirus

8-related primary effusion lymphoma in four HIV-uninfected patients

without organ transplantation. Respirology Case Reports. 2020;8:e00508.

https://doi.org/10.1002/rcr2.508

- Parente

P, Zanelli M, Zizzo M, Covelli C, Carosi I, Ascani S, Graziano P.

Primary effusion lymphoma metachronous to multicentric Castleman

disease in an immunocompetent patient. Pathology Research and Practice.

2020;216:153024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prp.2020.153024

- Yuan

L, Cook JR, Elsheikh TM. Primary effusion lymphoma in human immune

deficiency (HIV)-negative non-organ transplant immunocompetent

patients. Diagnostic Cytopathology. 2020;48: 380–385. https://doi.org/10.1002/dc.24371

- Rossi

G, Cozzi I, della Starza I, de Novi LA, de Propris MS, Gaeta A,

Petrucci L, Pulsoni A, Pulvirenti F, Ascoli V. Human

herpesvirus-8–positive primary effusion lymphoma in HIV-negative

patients: Single institution case series with a multidisciplinary

characterization. Cancer Cytopathology. 2021;129: 62–74. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncy.22344

- Chen

BJ, Wang RC, Ho CH, Yuan CT, Huang WT, Yang SF, Hsieh PP, Yung YC, Lin

SY, Hsu CF, Su YZ, Kuo CC, Chuang SS. Primary effusion lymphoma in

Taiwan shows two distinctive clinicopathological subtypes with rare

human immunodeficiency virus association. Histopathology. 2018;72:

930–944. https://doi.org/10.1111/his.13449

- Fernández-Trujillo

L, Bolaños JE, Velásquez M, García C, Sua LF. Primary effusion lymphoma

in a human immunodeficiency virus-negative patient with unexpected

unusual complications: A case report. Journal of Medical Case Reports.

2019;23:13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-019-2221-6

- Régnier-Rosencher

E, Guillot B, Dupin N. Treatments for classic Kaposi sarcoma: A

systematic review of the literature. Journal of the American Academy of

Dermatology. 2013;68: 313–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2012.04.018

- Lospalluti

M, Mastrolonardo M, Loconsole F, Conte A, Rantuccio F. Classical

Kaposi’s sarcoma: A survey of 163 cases observed in Bari, South Italy.

Dermatology. 1995;191: 104–108. https://doi.org/10.1159/000246525

- Goedert

JJ, Vitale F, Lauria C, Serraino D, Tamburini M, Montella M, Messina A,

Brown EE, Rezza G, Gafà L, Romano N. Risk factors for classical

Kaposi’s sarcoma. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2002;94:

1712–1718. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/94.22.1712

- Brenner

B, Weissmann-Brenner A, Rakowsky E, Weltfriend S, Fenig E,

Friedman-Birnbaum R, Sulkes A, Linn S. Classical Kaposi sarcoma:

Prognostic factor analysis of 248 patients. Cancer. 2002;95: 1982–1987.

https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.10907

- Stratigos

AJ, Malanos D, Touloumi G, Antoniou A, Potouridou I, Polydorou D,

Katsambas AD, Whitby D, Mueller N, Stratigos JD, Hatzakis A.

Association of clinical progression in classic Kaposi’s sarcoma with

reduction of peripheral B lymphocytes and partial increase in serum

immune activation markers. Archives of Dermatology. 2005;141:

1421–1426. https://doi.org/10.1001/archderm.141.11.1421

- Cottoni

F, Masala MV, Pattaro C, Pirodda C, Montesu MA, Satta R, Cerimele D, de

Marco R. Classic Kaposi sarcoma in northern Sardinia: A prospective

epidemiologic overview (1977-2003) correlated with malaria prevalence

(1934). Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2006;55:

990–995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2006.03.007

- Brambilla

L, Bellinvia M, Tourlaki A, Scoppio B, Gaiani F, Boneschi V.

Intralesional vincristine as first-line therapy for nodular lesions in

classic Kaposi sarcoma: A prospective study in 151 patients. British

Journal of Dermatology. 2010;162: 854–859. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09601.x

- Errihani

H, Berrada N, Raissouni S, Rais F, Mrabti H, Rais G. Classic Kaposi’s

sarcoma in Morocco: Clinico-epidemiological study at the national

institute of oncology. BMC Dermatology. 2011;11:15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-5945-11-15

- Régnier-Rosencher

E, Boutron I, Avril MF, Dupin N. Do anti-hypertensive renin-angiotensin

system inhibitors contribute to the development of classical Kaposi

sarcoma? Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and

Venereology. 2016;30: 1199–1201. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.13120

- Cetin

B, Aktas B, Bal O, Algin E, Akman T, Koral L, Kaplan MA, Demirci U,

Uncu D, Ozet A. Classic Kaposi’s sarcoma: A review of 156 cases.

Dermatologica Sinica. 2018;36: 185–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsi.2018.06.005

- Kandaz

M, Bahat Z, Guler OC, Canyilmaz E, Melikoglu M, Yoney A. Radiotherapy

in the management of classic Kaposi’s sarcoma: A single institution

experience from Northeast Turkey. Dermatologic Therapy. 2018;31:e12605.

https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.12605

- Marcoval

J, Bonfill-Ortí M, Martínez-Molina L, Valentí-Medina F, Penín RM,

Servitje O. Evolution of Kaposi sarcoma in the past 30 years in a

tertiary hospital of the European Mediterranean basin. Clinical and

Experimental Dermatology. 2019;44: 32–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/ced.13605

- Denis

D, Seta V, Regnier-Rosencher E, Kramkimel N, Chanal J, Avril MF, Dupin

N. A fifth subtype of Kaposi’s sarcoma, classic Kaposi’s sarcoma in men

who have sex with men: a cohort study in Paris. Journal of the European

Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2018;32: 1377–1384. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.14831

- Richetta

A, Amoruso GF, Ascoli V, Natale ME, Carboni V, Carlomagno V, Pezza M,

Cimillo M, Maiani E, Mattozzi C, Calvieri S. PEL, Kaposi’s sarcoma

KSHV/HHV-8+ and idiopathic T-lymphocitopenia CD4+. Clinica Terapeutica.

2007;158: 151–155.

- Countries with the oldest population in the world. [cited 13 Sep 2021]. https://www.prb.org/resources/countries-with-the-oldest-populations-in-the-world/

- Berberich

S, Förster R, Pabst O. The peritoneal micromilieu commits B cells to

home to body cavities and the small intestine. Blood.

2007;109:4627-4634. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2006-12-064345

- Banke

A, Schou M, Videbæk L, Møller JE, Torp-Pedersen C, Gustafsson F, Dahl

JS, Køber L, Hildebrandt PR, Gislason GH. Incidence of cancer in

patients with chronic heart failure: A long-term follow-up study.

European Journal of Heart Failure. 2016;18: 260–266. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.472

- Ascoli

V, lo Coco F, Artini M, Levrero M, Fruscalzo A, Mecucci C. Primary

effusion Burkitt’s lymphoma with t(8;22) in a patient with hepatitis C

virus related cirrhosis. Human Pathology. 1997;28: 101–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0046-8177(97)90287-2

- Vogt

A, Schmid S, Heinimann K, Frick H, Herrmann C, Cerny T, Omlin A.

Multiple primary tumours: Challenges and approaches, a review. ESMO

Open. 2017;2:e000172 https://doi.org/10.1136/esmoopen-2017-000172

- Luciani

A, Ascione G, Marussi D, Oldani S, Caldiera S, Bozzoni S, Codecà C,

Zonato S, Ferrari D, Foa P. Clinical analysis of multiple primary

malignancies in the elderly. Medical Oncology. 2009;26: 27–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-008-9075-x

- Iscovich

J, Boffetta P, Franceschi S, Azizi E, Sarid R. Classic Kaposi sarcoma:

Epidemiology and risk factors. Cancer. 2000;88: 500–517. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(20000201)88:3<500::AID-CNCR3>3.0.CO;2-9

- Franceschi

C, Garagnani P, Parini P, Giuliani C, Santoro A. Inflammaging: a new

immune–metabolic viewpoint for age-related diseases. Nature Reviews

Endocrinology. 2018;14:576-590. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-018-0059-4

- Ascoli

V, Calabrò ML, Giannakakis K, Barbierato M, Chieco-Bianchi L, Gastaldi

R, Narciso P, Gaidano G, Capello D. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated

herpesvirus/human herpesvirus 8-associated polyclonal body cavity

effusions that mimic primary effusion lymphomas. International Journal

of Cancer. 2006;119: 1746–1748. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.21965

- Boulanger

E, Gérard L, Gabarre J, Molina JM, Rapp C, Abino JF, Cadranel J,

Chevret S, Oksenhendler E. Prognostic factors and outcome of human

herpesvirus 8-associated primary effusion lymphoma in patients with

AIDS. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23: 4372–4380. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2005.07.084

- Vega

F, Miranda RN, Medeiros LJ. KSHV/HHV8-positive large B-cell lymphomas

and associated diseases: a heterogeneous group of lymphoproliferative

processes with significant clinicopathological overlap. Mod Pathol.

2020 Jan;33(1):18-28. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-019-0365-y

- Hu

Z, Pan Z, Chen W, Shi Y, Wang W, Yuan J, Wang E, Zhang S, Kurt H, Mai

B, Zhang X, Liu H, Rios AA, Ma HY, Nguyen ND, Medeiros LJ, Hu S.

Primary Effusion Lymphoma: A Clinicopathological Study of 70 Cases.

Cancers (Basel). 2021 Feb 19;13(4):878. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13040878

[TOP]