Guiping Liao2,*, Yali Zhou2,*, Xiaolin Yin2, Sheng He3, Yi Wu4, Jian Xiao1, Zhili Geng2, Qiuying Huang2, Ganghui Luo5 and Kun Yang1.

1 Department of Hematology, Zigong First People's Hospital, Zigong, China.

2

Department of Hematology, The 923rd Hospital of the Joint Logistics

Support Force of the People's Liberation Army, Nanning, China.

3

Department of Genetic and Metabolic Laboratory, Guangxi Zhuang

Autonomous Region Women and Children Health Care Hospital, Nanning,

China.

4 Department of Hematology, Guangan People's Hospital, Guangan, China

5

Department of Laboratory Medicine, The 923rd Hospital of the Joint

Logistics Support Force of the People's Liberation Army, Nanning, China.

* These authors contributed equally to this work.

Correspondence to: Kun

Yang. Department of Hematology, Zigong First People's Hospital, Zigong,

China. Tel: +86-15181977603. E-mail:

1759874951@qq.com

Published: May 1, 2022

Received: January 16, 2022

Accepted: April 4, 2022

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2022, 14(1): e2022034 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2022.034

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Background: IVS-II-5 G>C (HBB: c.315+5 G>C)

is a rare β-thalassemia mutation. However, there is no clear evidence

regarding the effect of this defect or co-inheritance of other

β-thalassemia mutations on phenotypes.

Methods:

The clinical phenotypes associated with compound heterozygosity for the

IVS-II-5 G>C mutation and other β-thalassemia mutations, together

with the genetic modifiers' potential effect of the genetic modifiers

α-thalassemia, were studied in 13 patients. In addition, analyses of

red cell indices, hemoglobin component, iron status, and α-globin genes

were carried out in 19 heterozygotes.

Results:

Next-generation sequencing of 24 undiagnosed patients with

transfusion-dependent thalassemia (TDT) or non-transfusion-dependent

thalassemia (NTDT) identified 13 carriers of the IVS-II-5 G>C

mutation. There was a wide spectrum of phenotypic severity in compound

heterozygotes and 6 (46.2%) of 13 were transfusion dependent. Analysis

of 19 heterozygotes indicated that most were hematologically normal

without appreciable microcytosis or hypochromia, and approximately half

had normal hemoglobin A2 levels at the same time.

Conclusion:

Compound heterozygotes for IVS-II-5 G>C and other severe

β-thalassemia mutations are phenotypically severe enough to necessitate

appropriate therapy and counselling. Co-inheritance of this nucleotide

substitution with other β-thalassemia mutations may account for a

considerable portion of the incidence of undiagnosed patients with NTDT

and TDT in Guangxi. Therefore, the IVS-II-5 G>C mutation can pose

serious difficulties in screening and counselling.

|

Introduction

β-Thalassemia is a genetic hemolytic disease caused by a reduction (β+ allele) or deletion (β0

allele) of the beta globin gene. So far, more than 350 pathogenic

genetic mutations with a high degree of genetic heterogeneity based on

geographical location and race have been associated with β-thalassemia.[1]

Further elucidation of the genotype/phenotype relationship could

benefit phenotype prediction for genetic counseling of at-risk couples

and appropriate clinical treatment for homozygous or compound

heterozygous patients. Usually, in the heterozygous state,

β-thalassemia is characterized by mild microcytic hypochromic anemia

and increased hemoglobin A2 (HbA2)

levels. However, some β-globin mutations are very mild or silent. Thus,

heterozygote carriers have normal hematological indices and

electrophoretic fractions. These specific defects to the β-globin gene

can be identified by genetic and molecular analyses.[2,3]

The rare IVS-II-5 G>C (HBB: c.315+5 G>C)

mutation of the β-globin gene was first observed in a family in

Guangxi, China. The proband and her two brothers were compound

heterozygous for two mutations: the IVS-II-5 G>C substitution and

the deletion -TCTT from codons 41–42 (HBB: c.126_129delCTTT). These mutations resulted in severe anemia, requiring regular blood transfusions.[4] In addition, Zhao et al.[5] reported a patient with normal red blood cell indices and borderline HbA2 levels, which was found to be compound heterozygous for the IVS-II-5 G>C and IVS-II-672 A>C (HBB: c.316-179 A>C)

mutations. There is no clear evidence regarding the effect of this

defect or co-inheritance of other β-globin gene mutations on

phenotypes. This study describes 32 individuals with the IVS-II-5

G>C mutation, including 19 heterozygous and 13 with co-inheritance

of the β0-thalassemia mutation. In

addition, the clinical and hematological phenotypes of heterozygotes

with the very rare IVS-II-5 G>C variant or compound heterozygotes

with β0-thalassemia mutations and the importance of genetic counseling are discussed.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects.

The subjects were selected from undiagnosed patients presenting with

transfusion dependent thalassemia (TDT) or non-transfusion dependent

thalassemia (NTDT) and relatives. The gap-polymerase chain reaction

(Gap-PCR) and reverse dot-blot (RDB) technique were previously

performed to investigate the incidences of 17 common types of Chinese

β-thalassemia mutations [-28 A>G (HBB: c.-78 A>G), -29 A>G

(HBB: c.-79 A>G), -30 T>C (HBB: c.-80 T>C), -32 C>A (HBB: c.-82 C>A), codons 14/15 +G (HBB: c.45_46insG), codon 17 A>T (HBB: c.52 A>T), codon 26 G>A (HbE or HBB: c.79 G>A), codons 27–28 +C (HBB: c.84_85G), codon 31 -C (HBB: c.94delC), codons 41–42 -TCTT (HBB: c.126_129delCTTT), codon 43 G>T (HBB: c.130 G>T), codons 71-72 +A (HBB: c.216_217insA), IVS-I-1 G>T (HBB: c(0).92+1 G>T), IVS-I-5 G>C (HBB: c.92+5 G>C), IVS-II-654 C>T (HBB: c.316-197 C>T), Cap+40-43 -AAAC (HBB: c.11_-8delAAAC), and codon ATG>AGG (HBB: c.2 T>G)] and six common Chinese α-thalassemia mutations [– –SEA (South East Asian) deletion, –α3.7 (rightward) and –α4.2 (leftward) deletions and Hb Constant Spring (Hb CS; HBA2: c.427 T>C), Hb Quong Sze (Hb QS; HBA2: c.377 T>C) and Hb Westmead (HBA2: c.369 C>G) point mutations] in the undiagnosed patients.[6]

Genotypic analysis using traditional methods.

The family members were analyzed with Gap-PCR and RDB methods on the

common types of Chinese thalassemia mutations. In addition, the.

Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification was conducted to

identify variations in α and β gene copy numbers for the undiagnosed

patients and their family members.

Genetic sequencing.

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood samples using the

MagCore® Genomic DNA Whole Blood Kit (ATRiDA B.V., Amersfoort,

Netherlands). A library was constructed using the Twist Library

Preparation Kit Twist Comprehensive Exome 96 Reactions Kit (Twist

Bioscience, South San Francisco, CA, USA). Next-generation sequencing

(NGS) was performed to screen potential variants using the Illumina

NovaSeq sequencing platform (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) with a

sequencing read length of PE150. This procedure included whole-exome

sequencing for nearly 700 genes related to hematological hereditary and

immunodeficiency disorders based on NGS. In addition, Sanger sequencing

was performed to confirm the presence or absence of these mutations.

Hematological analysis.

Complete blood counts were analyzed using an XE 5000 automatic blood

cell analyzer (Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan). Fetal hemoglobin (HbF)

and HbA2 levels were quantified by

high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) (VARIANT II Hemoglobin

Testing System; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) and capillary

electrophoresis (Sebia, Lisses, France). Serum iron and ferritin levels

were measured using a Cobas 6000 chemistry analyzer (Roche Diagnostics,

Mannheim, Germany). Total iron-binding capacity was determined using a

BN ProSpec® System (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany).

Results

Of

the 24 undiagnosed patients with TDT or NTDT, 13 (54.2%) were compound

heterozygous for the IVS-II-5 G>C mutation and a second β0

gene mutation (-TCTT at codons 41–42 in seven, A>T at codon 17 in

five, and +A at codons 71–72 in one). The clinical phenotype was TDT in

six patients and NTDT in seven. The details of the genotypes and

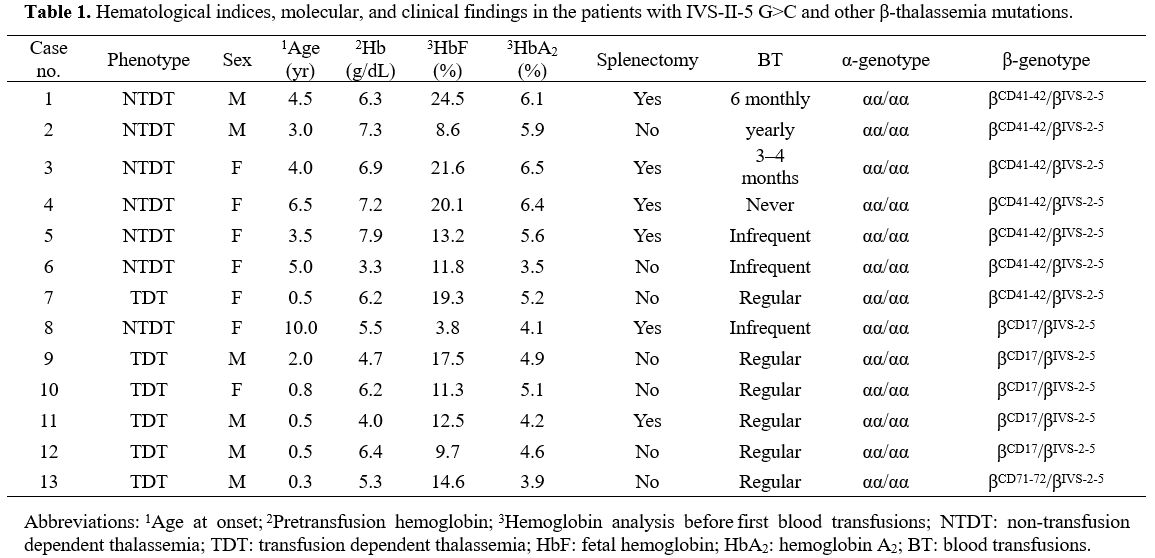

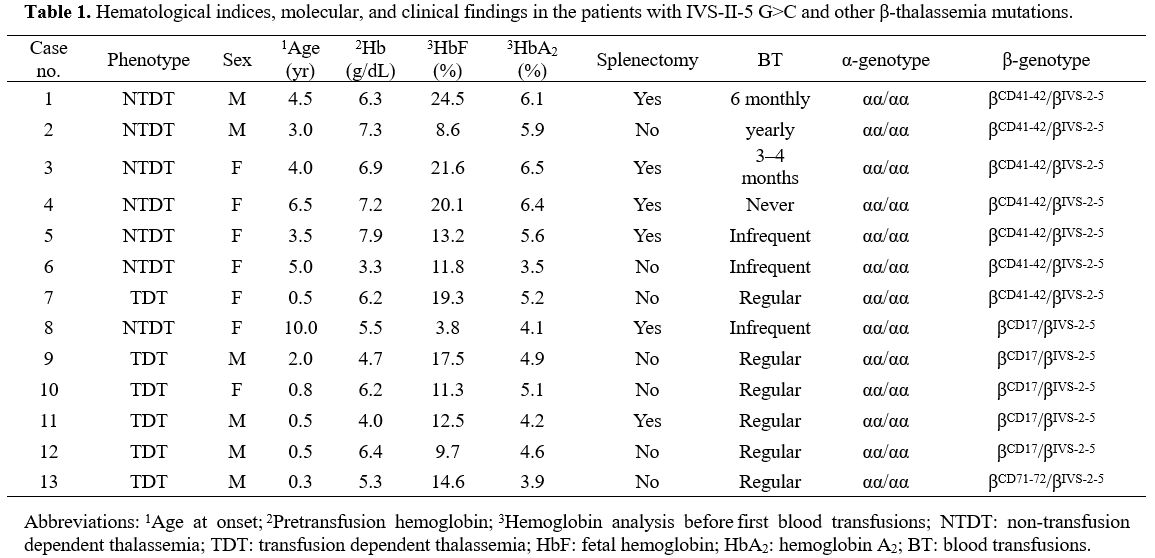

phenotypes are described in Table 1.

|

Table 1. Hematological

indices, molecular, and clinical findings in the patients with IVS-II-5

G>C and other β-thalassemia mutations. |

The

age of onset, pretransfusion hemoglobin (Hb) levels, and number and

frequency of transfusions were obtained from the patient's records. All

patients were compound heterozygotes and at diagnosis before the age of

5 years, except two at ages of 6.5 and 10. Seven patients had received

variable numbers of blood transfusions before being referred.

Hemoglobin analysis before the first transfusion found that these

patients had increased levels of HbF (range, 3.8%–24.5%) and HbA2

(3.5%–6.5%) to various degrees. The mean pretransfusion Hb

concentration of the six patients with the TDT phenotype was 5.5

(range, 4.0–6.4) g/dL. All patients had mild to moderate splenomegaly

at the time of presentation. During the follow-up period, six patients

underwent splenectomy (Table 1).

Compound heterozygotes for the IVS-II-5 G>C and -TCTT at codons 41–42. Of

the seven patients with the IIS-II-5 G>C and -TCTT at codons 41–42

genotype, 6 (85.7%) had the NTDT phenotype. One had never received a

transfusion, three required occasional blood transfusions, and one

received 3-4 blood transfusions each year after disease onset, but

transfusions were no longer necessary after splenectomy. Another

patient with TDT received 1–2 transfusions per month.

Compound heterozygotes for the IVS-II-5 G>C and A>T at codon 17 mutations. Of

the five patients with the IVS-II-5 G>Cand A>T at codon 17

genotype, 4 (80.0%) had the TDT phenotype, including three who required

monthly blood transfusions, while the fourth died from anemic heart

disease. The remaining patient had the NTDT phenotype and rarely

required transfusion at the disease onset.

Compound heterozygotes for the IVS-II-5 G>C and +A at codons 71–72.

One case with the IVS-II-5 G>C and +A at codons 71–72 genotype

required one blood transfusion per month at disease onset. This patient

received hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and Hb levels

remained at >7 g/dL afterwards.

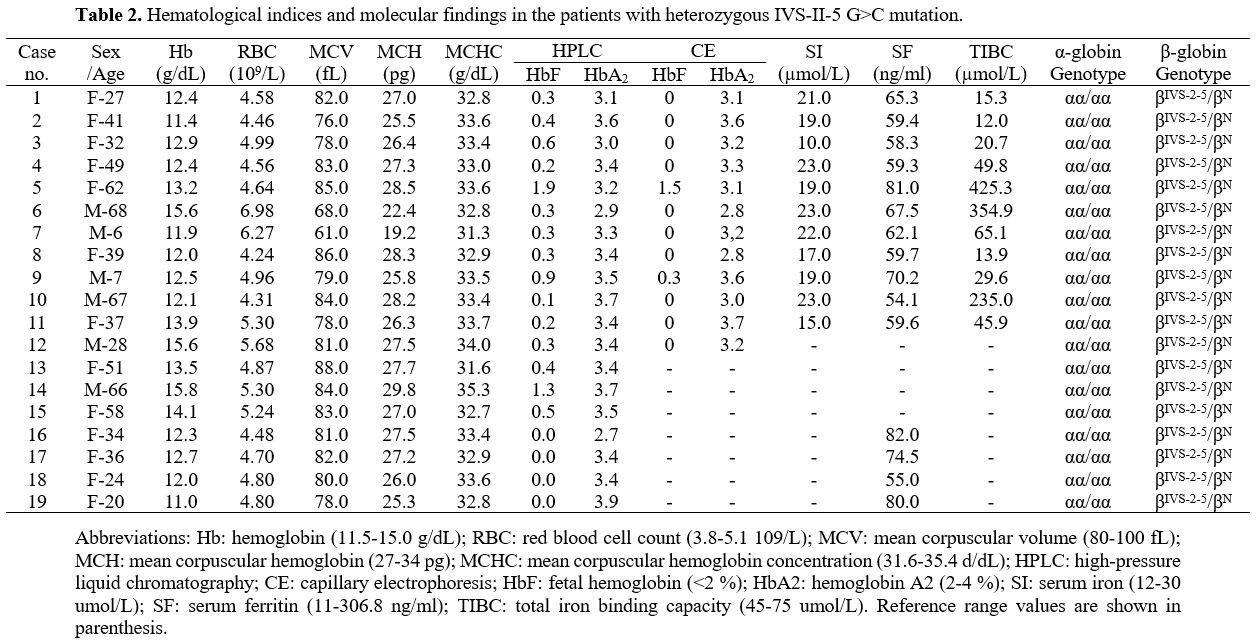

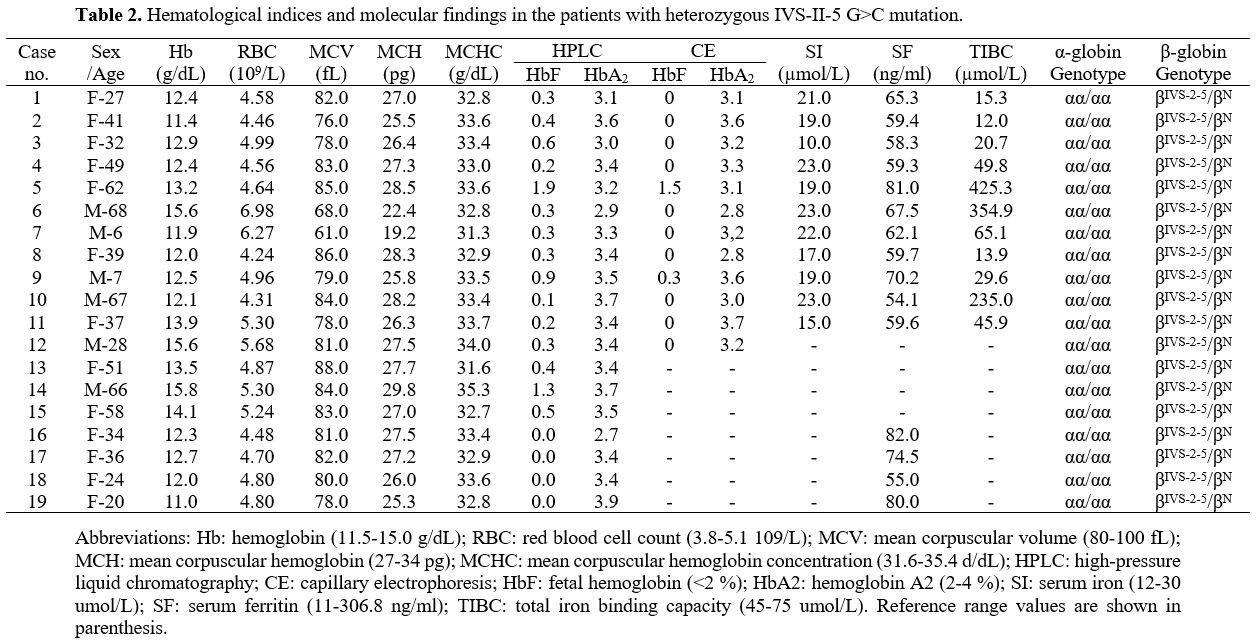

IVS-II-5 G>C in a heterozygous state. Nineteen

individuals (six men and 13 women; age range, 6–68 years) heterozygous

for the IVS-II-5 G>C mutation were screened from 42 relatives. None

had co-inherited α-thalassemia. Iron deficiency anemia was ruled out in

15 carriers, as Hb levels were 11.0–15.0 g/dL. The mean corpuscular

volume (MCV) was > 80 (reference range, 80–100) fL in 12 (63.2%)

individuals and the mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH) was > 27

(reference range, 27–34) pg in 11 (57.9%). HbA2 levels measured by HPLC ranged from 2.7% to 3.9%. When defining HbA2 ≥ 4.0% as abnormal, 3.5%–4.0% as critical, and <3.5% as normal, 13 (68.4%) of the 19 patients had normal HbA2 levels, while six were considered critical. Eight patients with MCV and HbA2

were completely normal (cases 1, 4, 5, 8, 12, 13, 16, and 17), which

included five who received capillary electrophoresis, suggested that HbA2 levels were in the normal range (<3.5%) (Table 2).

|

Table

2. Hematological indices and molecular findings in the patients with heterozygous IVS-II-5 G>C mutation. |

Discussion

Molecular

defects causing β-thalassemia are mainly due to point mutations, few

deletions, dysregulation of the globin gene, or an insert in the coding

region. A previous study conducted in Guangxi province, China, revealed

the presence of few frequent mutations and a large number of rare

defects associated with molecular heterogeneity. A large-scale

epidemiological survey conducted in Guangxi reported that the carrier

rate of the IVS-II-5 G>C mutation was 0.02%.[7] No IVS-II-5 G>C mutation was detected in the screening of 47,500 people in Baise city[8] or 130,318 in Yulin city in Guangxi.[9] Only one case with the IVS-II-5 G>C mutation was identified among 189,414 individuals screened in Fujian, China.[10]

These studies confirmed that the IVS-II-5 G>C mutation is rare in

the Chinese population. However, in the present study, 13 (54.2%) of

the 24 undiagnosed patients with TDT or NTDT had co-inherited the

IVS-II-5G>C mutation, which included 7 (53.8%) from Hechi City. In

addition, 13 (68.4%) of the 19 heterozygous were from Hechi City, which

was not included in the large-scale epidemiological survey previously

conducted in Guangxi. Hence, it seemed that the mutation was

concentrated in Hechi city. However, a large-scale epidemiological

investigation is needed to confirm this suspicion.

There have been

relatively few reported cases of co-inheritance of the IVS-II-5 G>C

mutation compounded with other β-thalassemia mutations. Thus, the

impact on phenotype remains unclear.[4,5,11]

Three cases previously reported with the IVS-II-5 G>C mutation

compounded with -TCTT at codons 41–42 had transfusion-dependent

thalassemia. Only one (14.3%) of seven patients in the present study

had the TDT phenotype, while 6 (85.7%) had the NTDT phenotype.

Interestingly, one patient required 3–4 blood transfusions per year but

no longer after splenectomy. In addition, blood transfusions were no

longer needed after splenectomy in three patients, as Hb levels were

maintained at >6.8 g/dL.[11] The efficacy of

splenectomy for the treatment of thalassemia is dependent on the

destruction site of red blood cells. However, the efficacy of

splenectomy is poor in some patients with ineffective hematopoiesis,[12]

suggesting a greater extent of erythrocyte destruction in the spleen of

patients with the IVS-II-5 G>C mutation as compared to those with

other types of β-thalassemia. Hence, splenectomy is relatively

effective in these patients. Clinical manifestations were more severe

with the IVS-II-5 G>C/codon 17 A>T genotype, as most patients had

the TDT phenotype. In patients with the IVS-II-5 G>C and +A at

codons 71–72, our data were insufficient to predict the phenotype as

only one was diagnosed with TDT. Among the patients with severe disease

in the present study, none carried both IVS-II-5 and β+-thalassemia

mutations, which indirectly confirmed that the clinical symptoms might

not be severe for patients with IVS II-5 G>C and β+-thalassemia mutations. Zhao et al.[5]

reported a case of compounded heterozygosity for IVS II-5 G>C and

IVS-II-672 A>C with normal Hb and MCV levels, although there is no

evidence that the IVS-II-672 A>C sequence variant is pathogenic. In

addition, although the influence of co-inheritance of α-thalassemia on

the phenotype was ruled out, the influence of other globin gene

modifications on the severity of clinical presentation remains unclear.

Analysis

of heterozygotes with the IVS-II-5 G>C mutation showed that in 12

(63.2%) of 19 individuals, MCV was > 80 (reference range, 80–100) fL

and in 11 (57.9%) of 19, MCH was >27 (reference range, 27–34) pg.

When screening β-thalassemia carriers, it is not uncommon to identify

individuals with normal or mildly reduced red cell indices. Subjects

with this phenotype may be carriers of very mild or silent β-gene

mutations associated with high residual β-globin chain output. Unlike

the IVS-II-1 G>T mutation, which causes β0-thalassemia, the IVS-II-5 G>C mutation did not completely abolish normal splicing.[11] Jiang et al.[11]

found that normally spliced RNA was the dominant form of the IVS-II-5

G>C mutation. Therefore, co-inheritance of α-thalassemia has a

significant effect on red cell indices, particularly the MCV and MCH,

which may be normalized.[13] Furthermore, mutations to the KLF1 gene have been associated with normal MCV and MCH.[14]

Although co-inheritance of α-thalassemia was excluded from our cohort,

and other factors may contribute to differences in RBC parameters

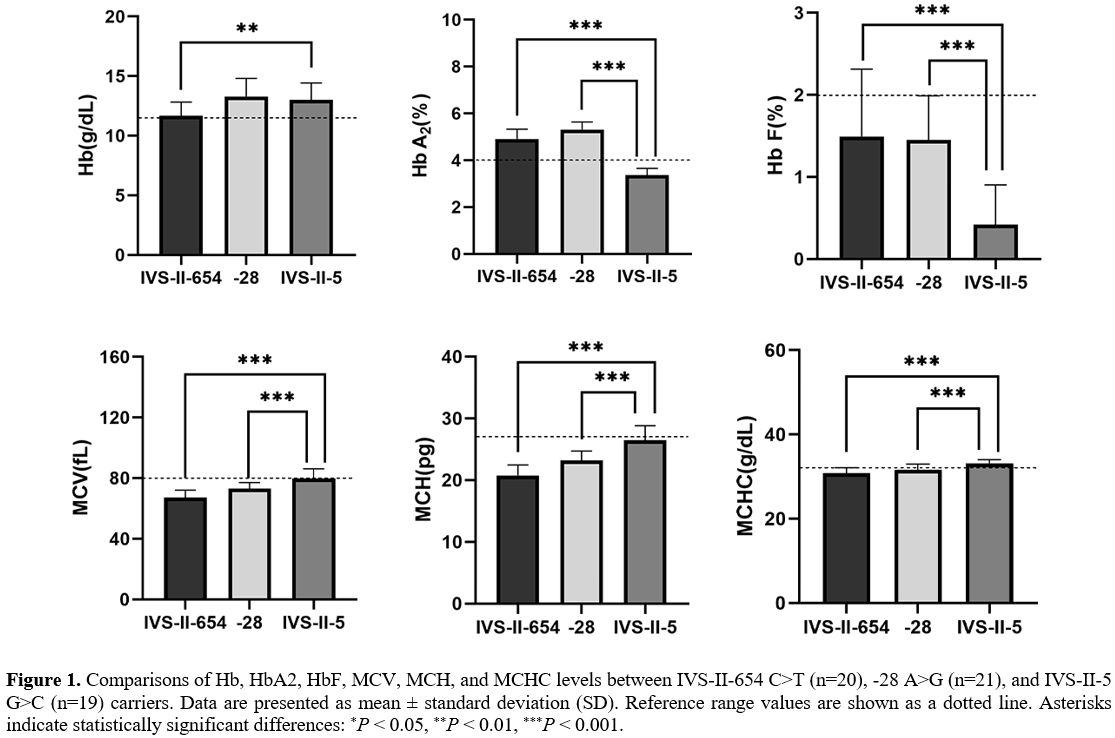

between individuals. The HbA2

levels of all heterozygotes were <4.0%, of which 13 (68.4%) were

below the diagnostic cutoff of 3.5%. Of the 19 heterozygotes for the

IVS-II-5 G>C mutation, 8 (42.1%) were silent with completely normal

HbA2

and MCV levels. Because whole blood cell and Hb composition analysis

are required for a diagnosis of anemia and screening of thalassemia,

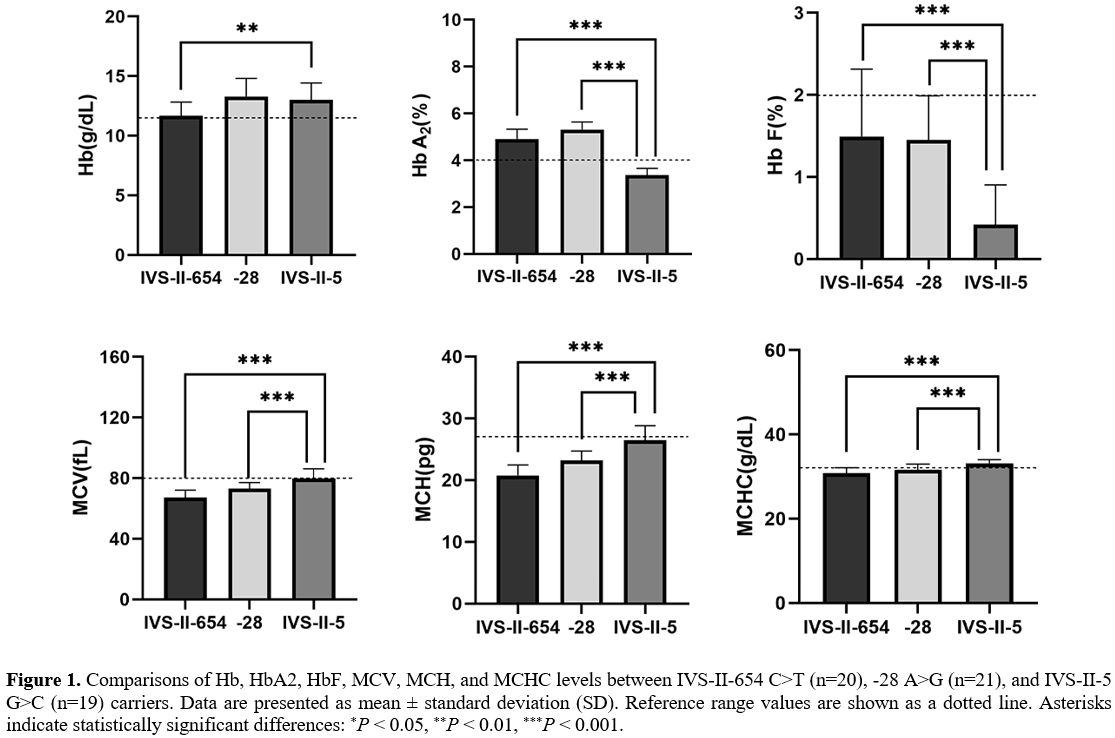

the key RBC parameters and the constitution of Hb were compared among

patients with other β+-thalassemia mutations or IVS-II-5 G>C

carriers (Figure 1). Significant differences in HbA2,

HbF, MCV, MCH, and MCHC values were evident between patients with other

β+-thalassemia mutations (IVS-II-654 C>T or -28 A>G) and IVS-II-5

G>C carriers (P<0.001). IVS-II-5 G>C carriers have significantly higher Hb levels than IVS-II-654 C>T carriers (P=0.002).

Thus, the IVS-II-5 G>C mutation is responsible for milder anemia

than other mutations described in China, although the variant was

described as the β+ hematological phenotype in a prior publication.[11]

Based solely on the screening results, there was no indication of

β-thalassemia, which is prone to a missed diagnosis. In addition, the

IVS-II-5 G>C defect is undetectable by traditional methods. DNA

sequencing is usually required, which prevents the detection of more

patients and missed diagnoses, and may eventually have adverse

consequences in genetic counseling. Thus, it is recommended that if a

partner is diagnosed as a carrier of thalassemia and indices and HbA2 are borderline, then molecular screening for the IVS-II-5 G>C mutation by NGS should be performed.

|

Figure 1. Comparisons of

Hb, HbA2, HbF, MCV, MCH, and MCHC levels between IVS-II-654 C>T

(n=20), -28 A>G (n=21), and IVS-II-5 G>C (n=19) carriers. Data

are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Reference range values

are shown as a dotted line. Asterisks indicate statistically

significant differences: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. |

Conclusions

In

conclusion, the present study results showed that co-inheritance of the

IVS-II-5 G>C defect with other mutations to globin genes may account

for a considerable portion of the incidence of undiagnosed moderate and

severe β-thalassemia in Guangxi. On the other hand, MCV and HbA2 levels

in most patients heterozygous for IVS-II-5 G>C were normal and,

thus, often misdiagnosed. Hence, routine screening of this nucleotide

substitution and NGS are recommended for genetic counseling of

suspected cases, especially in populations with a significantly high

frequency.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to our patients for participating in this study.

Ethic statement

The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the 923rd

Hospital of the Joint Logistics Support Force of the People's

Liberation Army and the First People's Hospital of Zigong. All patients

provided written informed consent.

Funding

This

study was supported by the Scientific Research Project of Guangxi

Zhuang Autonomous Region Health Committee (Z20201266) and Key Science

and Technology Project of Zigong (2020YXY04).

References

- Taher AT, Musallam KM, Cappellini MD. β-Thalassemias. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(8):727-43. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra2021838 PMid:33626255

- Weatherall

DJ. Phenotype-genotype relationships in monogenic disease: lessons from

the thalassaemias. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2(4):245-55. https://doi.org/10.1038/35066048 PMid:11283697

- Higgs DR. The molecular basis of α-thalassemia. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2013;3(1):a011718. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a011718 PMid:23284078 PMCid:PMC3530043

- Jiang

NH, Liang S, Su C, Nechtman JF, Stoming TA. A novel beta-thalassemia

mutation [IVS-II-5 (G-->C)] in a Chinese family from Guangxi

Province, P.R. China. Hemoglobin. 1993;17(6):563-7. https://doi.org/10.3109/03630269309043498 PMid:8144358

- Zhao

L, Qing J, Liang Y, Chen Z. A novel compound heterozygosity in Southern

China: IVS-II-5 (G > C) and IVS-II-672 (A > C). Hemoglobin.

2016;40(6):428-30. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630269.2016.1252387 PMid:27829298

- Viprakasit

V, Ekwattanakit S. Clinical Classification, Screening and Diagnosis for

Thalassemia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2018;32(2):193-211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hoc.2017.11.006 PMid:29458726

- Xiong

F, Sun M, Zhang X, Cai R, Zhou Y, Lou J, et al. Molecular

epidemiological survey of haemoglobinopathies in the Guangxi Zhuang

Autonomous Region of southern China. Clin Genet. 2010;78(2):139-48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01430.x PMid:20412082

- He

S, Qin Q, Yi S, Wei Y, Lin L, Chen S, et al. Prevalence and genetic

analysis of α- and β-thalassemia in Baise region, a multi-ethnic region

in southern China. Gene. 2017;619:71-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2016.02.014 PMid:26877226

- He

S, Li J, Li DM, Yi S, Lu X, Luo Y, et al. Molecular characterization of

α- and β-thalassemia in the Yulin region of Southern China. Gene.

2018;655:61-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2018.02.058 PMid:29477874

- Huang

H, Xu L, Chen M, Lin N, Xue H, Chen L, et al. Molecular

characterization of thalassemia and hemoglobinopathy in Southeastern

China. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):3493. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-40089-5 PMid:30837609 PMCid:PMC6400947

- Jiang

NH, Liang S. The beta+-thalassemia mutation [IVS-II-5 (G-->C]

creates an alternative splicing site in the second intervening

sequence. Hemoglobin. 1999;23(2):171-6. https://doi.org/10.3109/03630269908996161 PMid:10335984

- Al-Salem AH, Nasserulla Z. Splenectomy for children with thalassemia. Int Surg. 2002;87(4):269-73.

- Galanello

R, Paglietti E, Melis MA, Crobu MG, Addis M, Moi P, et al. Interaction

of heterozygous beta zero-thalassemia with single functional

alpha-globin gene. Am J Hematol. 1988;29(2):63-6. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.2830290202 PMid:3189303

- Perseu

L, Satta S, Moi P, Demartis FR, Manunza L, Sollaino MC, et al. KLF1

gene mutations cause borderline HbA(2). Blood. 2011;118(16):4454-8. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2011-04-345736 PMid:21821711

[TOP]