Saiduo Liu1, Wei Chen2, Jichan Shi1, Xinchun Ye1, Hongye Ning1, Ning Pan1 and Xiangao Jiang1.

1 Departments of Infectious Disease, Wenzhou Central Hospital, 32 West Jiangbin Road, Wenzhou, Zhejiang 325000, PR China.

2

Department of Radiology, The Second Affiliated Hospital and Yuying

Children's Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, Xueyuanxi Road, No

109, Wenzhou 325027, Zhejiang, PR China.

Correspondence to:

Xiangao Jiang, Department of Infectious Disease, Wenzhou Central

Hospital, 32 West Jiangbin Road, Wenzhou Zhejiang 325000, China. Tel:

+86 13676788085. Fax: +86 10 8316 1294. Email:

jxgjxg22@163.com

Published: September 1, 2022

Received: March 16, 2022

Accepted: August 6, 2022

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2022, 14(1): e2022063 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2022.063

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

To

understand the clinical and imaging manifestations and the treatment

and follow-up of hepatic tuberculosis (HTB), we retrospectively

analysed the clinical and imaging data of 29 patients with HTB who had

been diagnosed clinically or by biopsy, and the clinical and imaging

data had been summarised. Patient characteristics were followed up

after anti-TB drug treatment. The median age of the 29 patients with

HTB was 37 years, and most were male (58.6%). The patient's symptoms

included fever (48.2%), respiratory symptoms (27.5%), abdominal pain

(24.1%), and abdominal distension (10.3%). Elevated erythrocyte

sedimentation rate (79.3%), elevated serum C-reactive protein (75.8%)

and hypoalbuminemia (62.0%) were common features. Three patients were

serologically positive for acquired human immunodeficiency syndrome,

and two were serologically positive for hepatitis B surface antigen

with normal tumour markers. The 29 patients with HTB included 17 with

serous HTB, 9 with parenchymal HTB (8 with parenchymal nodular HTB and

1 with parenchymal miliary HTB), 1 with intrahepatic abscess type HTB,

and 2 with hilar HTB. Approximately 86% of the patients also had

pulmonary TB. Most of the serous HTB patients also had tuberculous

peritonitis. Enhanced computerized tomography scans of the serous and

parenchymal HTB cases showed the progressive development of lesions.

Abnormal blood perfusion was observed in the hepatic artery, and the

clearest evidence of TB was observed in the hepatic portal vein.

Magnetic resonance imaging indicated that the lesions returned a high

signal in the diffusion-weighted imaging sequence. However, the

lesions' apparent diffusion coefficient values reflected high signals.

The Xpert MTB/RIF test detected Mycobacterium TB complex in the liver

biopsy fluid from 10 patients.

Regarding histopathology, one

patient showed granulomatous inflammation, and one patient's acid-fast

bacillus (AFB) stain was positive. The treatment of two patients was

stopped due to their adverse reactions to the drugs and the risk of

creating drug-resistant TB. The remaining patients received anti-TB

treatment, but one subsequently died, and two were unavailable for

follow-up.

The clinical symptoms of HTB are difficult to detect,

and it has diverse manifestations by imaging, with no obvious

specificity in terms of pathological results. Therefore, follow-up of

liver lesions for checking anti-TB therapy is another method for

diagnosing HTB. In addition, early active anti-TB treatment can achieve

good curative results.

|

Introduction

Hepatic

tuberculosis (HTB) refers to TB resulting from a liver infection by

Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a rare extrapulmonary TB that accounts for

less than 1% of TB cases.[1] Bristowe reported the first documented case of HTB in 1858.[2]

More than 20 years after Koch's discovery of Mycobacterium

tuberculosis, Ileston and McNee classified HTB into miliary

(disseminated) and local (isolated) types in 1905, as reported by Chien

et al.[3] Miliary HTB is more common than local HTB in literature reports, where it represents 79% of HTB cases.[4]

The

main clinical manifestations of HTB are fever, cyanosis, jaundice,

shortness of breath, cough, moist lung rale, hepatomegaly,

splenomegaly, and abdominal distension. These indicators lack

characteristic clinical symptoms and specific imaging manifestations,

which can easily lead to a missed or misdiagnosis.[5] A retrospective study by Longxin et al. found a misdiagnosis rate of up to 91% for HTB.[6]

Several clinical studies have found that HTB can easily be misdiagnosed

as liver cancer, cholangiocarcinoma, or other malignant diseases.[5,7-8]

The

diagnosis of HTB is challenging, even in areas where TB is endemic, due

to the non-specificity and diversity of its clinical symptoms.

Statistically, HTB accounts for 1.5%-4.2% of digestive system diseases

manifested by fever and approximately 2.7% of active TB autopsies.[9] Garmpis et al.[10]

found that HTB was characterized by central caseous necrotic granuloma

with or without anti-acid bacteria, indicating that a liver biopsy of

suspected cases of HTB may be useful for the timely diagnosis and

treatment of the disease. A study conducted by Freitas et al.[11]

also indicated the important role of a liver biopsy in correctly

diagnosing HTB in patients with significant liver injury factors but

atypical clinical manifestations. Simultaneously Mycobacterium

tuberculosis complex detection and testing for rifampicin resistance

could be performed on this specimen using the Xpert MTB/RIF assay.[12]

The

current paper explores the clinical and imaging manifestations,

treatment, and follow-up of HTB to provide a practical basis for

suspecting and then diagnosing HTB.

Data and Methods

General data. Twenty-nine

HTB patients, 17 males and 12 females, who each underwent a biopsy with

effective diagnostic and anti-TB treatment in our hospital between

April 2012 and May 2021, were selected for this study. The age of the

patients ranged from 16 to 81 years, with a median age of 37 years.

There was no significant difference in the patients' geographical

distribution. Among the participants, 14 (48.2%) had a fever as the

first clinical manifestation, 7 (24.1%) had abdominal pain, and 8

(27.5%) had cough and sputum symptoms. The total number of patients

with TB at additional sites other than the lungs was 25 (86.2%). Among

these, seven had TB peritonitis, three had splenic TB, six had lymph

TB, three had spinal TB, and six had tuberculous pleuritis. In

addition, three patients had acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, two

had type 2 diabetes, two presented with fatty livers, and two had

chronic viral hepatitis B. Additionally, 23 patients (79.3%) had

elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rates (ESRs), 22 (75.8%) had

elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) levels and 18 (62.0%) had

hypoalbuminemia (see Tables 1 and 2). The disease course ranged from 6 to 24 months.

|

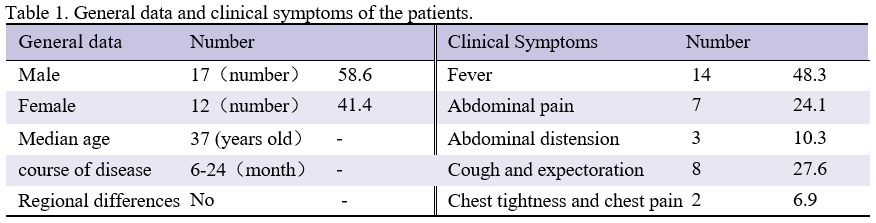

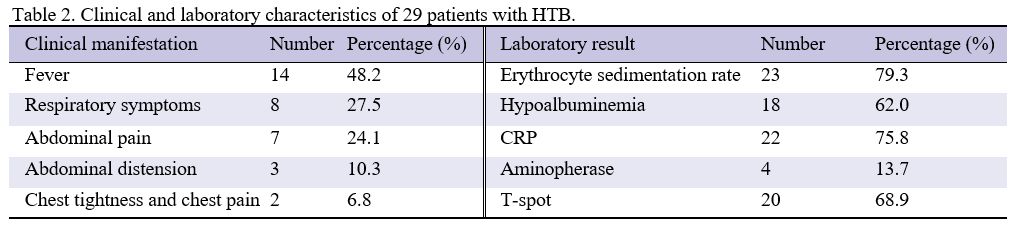

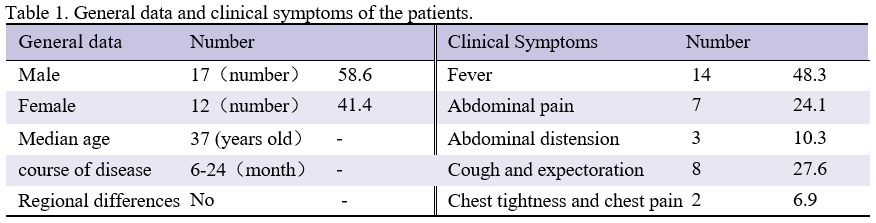

Table

1. General data and clinical symptoms of the patients. |

|

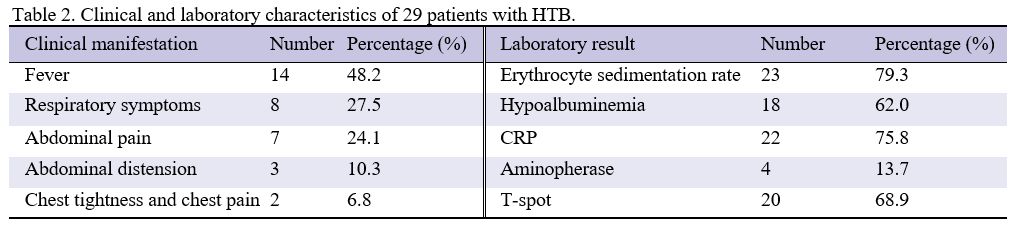

Table

2. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of 29 patients with HTB.

|

Methods. The

demographic data, clinical, laboratory, and imaging examinations, and

the pathological and microbiological outcomes of 29 patients with HTB

were analyzed. All patients were examined by computerized tomography

(CT) of the liver; some also had a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

scan for comparison. Plain and three-phase dynamic contrast enhancement

scans were performed using a LightSpeed or a Bright Speed Pro-16-layer

scanner (GE Healthcare, USA). The CT scanning requirements were set as

follows: 120 kV, 200-250 mA, and a pitch of 1.375. Some patients

underwent concurrent CT and MRI examinations. The MRI was performed

using a Philips Achieva 1.5 T superconducting-type MR instrument and an

abdominal surface coil for routine MRI examinations. In addition,

multiphase dynamic enhancement scanning was performed using the THRIVE

circum phase gradient echo sequence.

Statistical methods. Descriptive

statistics (mean, standard deviation, percentage, frequency count) were

calculated using the SPSS Statistics 17.0 software program. Categorical

data were examined using the chi-square test, and continuous data were

analysed using the analysis of variance.

Results

General data and clinical results.

Between April 2012 and May 2021, 29 patients in our hospital were

diagnosed with HTB. The median age in this cohort was 37 years (range =

16-81 years), and most patients were male (58.6%). Among the 29

patients, three had a history of close contact with pulmonary TB

patients, six (20.6%) had previously developed pulmonary TB, three were

seropositive for HIV, and two were positive for hepatitis B surface

antigen. Fever (48.2%), respiratory symptoms (27.5%), abdominal pain

(24.1%) and abdominal distension (10.3%) were common clinical features.

Common laboratory abnormalities included elevated ESR (79.3%), elevated

blood CRP (75.8%) and hypoalbuminemia (62.0%). Furthermore, 20 patients

had positive r-interferon tests (68.9%). All patients had normal tumour

markers (alpha foetoprotein [AFP] and carcinoembryonic antigen).

Initially, all patients received anti-TB therapy, but two patients

discontinued this due to their inability to tolerate the side effects.

Subsequently, one patient died of other causes, and two were

unavailable for follow-up (see Table 2).

The manifestations of hepatic tuberculosis seen by imaging.

The CT scans of the 29 patients showed primarily low-density foci,

including the 17 patients with serohepatic HTB showing mostly single

but sometimes multiple nodular lesions or hypertrophy on the liver

envelope.[13] Abnormal perfusion can occur in the

liver tissue adjacent to a lesion, which may be associated with altered

local vascular compression. The lesions observed during the enhanced

scanning of the delayed arterial phase showed progressive

intensification. The perihepatic parenchyma was compressed. The nine

patients with parenchymal HTB included eight with parenchymal nodular

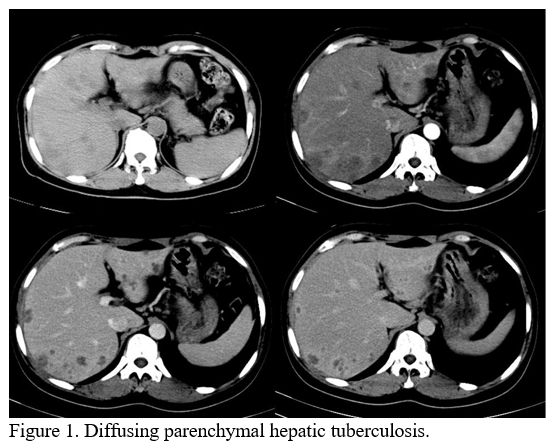

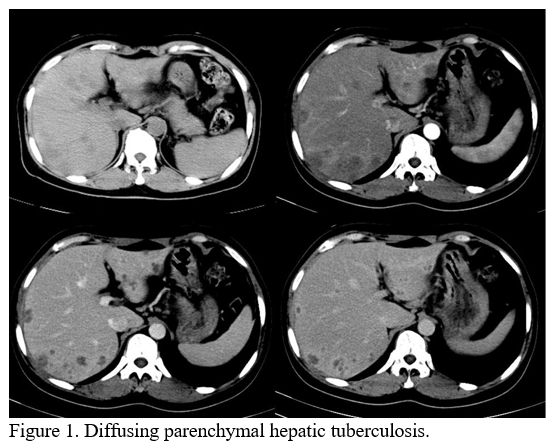

HTB and one with parenchymal miliary HTB (Figure 1).

The images of these two types of HTB are the same, except that the

miliary lesions are approximately 0.5-1 cm and the nodular lesions are

about 2-3 cm.[14-15] In plain CT scan images, the

lesions showed low or equal density shadows, blurred margins, and

low-density changes due to liquefaction or caseous necrosis at the

centre of the lesion. Abnormal peripheral blood perfusion or irregular

enhancement of blood pressure was observed during the enhanced scanning

arterial stage, and clearer lesions were indicated during the portal

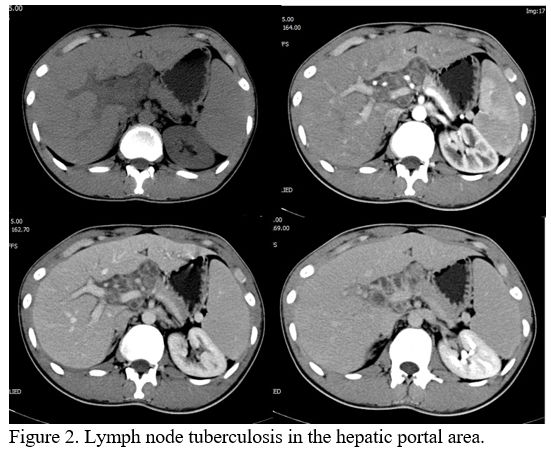

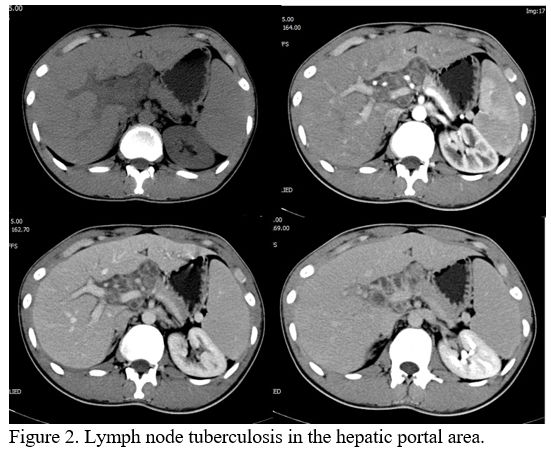

phase. Two patients with enlarged lymph nodes in the hilar area (Figure 2)

had no lesions in the liver parenchyma or subcapsular region. The

patients in this group included one with parenchymal abscess type TB

for whom the lesion was distributed through the right lobe of the

liver.

|

Figure 1. Diffusing parenchymal hepatic tuberculosis. |

|

Figure

2. Lymph node tuberculosis in the hepatic portal area.

|

There

was no enhancement in the central liquefied necrosis area of the

lesion, and a mild annular enhancement was observed around the lesion

during the delayed phase of the CT scan. The lesion showed a low signal

in the T1 weighted image (T1WI) and a high signal in that T2 weighted

(T2WI). Restricted focal diffusion on the diffusion-weighted (DW)

sequence produced a high alert, but the apparent diffusion coefficient

(ADC) value was also increased, suggesting a benign condition.

Pathological diagnosis of hepatic tuberculosis.

Of the 29 patients included in the study, 10 underwent an

ultrasound-guided liver biopsy for suspected HTB. The tissue (liquid)

samples were submitted for the Xpert MBT/RIF assay. Seven patients

tested positive. One had rifampicin-resistant TB, and one had TB that

was resistant to isoniazid and streptomycin. Two patients each

underwent a liver biopsy for pathology. One of these was found to have

granulomatous lesions; the other had no specific lesions. One patient

tested positive for AFB staining. Finally, ten patients underwent

biopsies (liquid) for Mycobacterium TB culture. Two patients tested

positive, and the remaining patients tested negative.

Treatment and follow-up.

Among the participants, 27 patients underwent 4-5 anti-TB drug

treatments (ATT) for 6-9 months. Two became resistant to anti-TB drugs

after 18 months of treatment. Six patients with a previous history of

TB and three with HIV received ATT for 12 months. One died of organ

failure before follow-up (not associated with TB). Two patients were

removed from the controls. Two patients refused further ATT due to drug

intolerance. At the end of the treatment phase, a low-dose CT scan was

performed on 25 patients, and the results indicated absorption of

lesions in all patients and improvement in their symptoms. No

significant adverse events related to treatment were observed in these

25 patients.

Discussion

Immunosuppressed

patients are more susceptible to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection,

and in recent years, TB, particularly in the hepatic manifestation, has

become more common in HIV-infected patients,[16-17]

indicating a close link between cellular immunity and HTB. There were

three cases of HIV infection among the participants in the current

study. The HTB patients were mostly aged 30-50 with a median age of 37,

and there were more men than women.[18-20] According to the literature, HTB patients with TB and TB contact history are uncommon.[20-21] In our study, five patients had a TB history, and three had close contact with TB patients.

Many

cases of HTB start slowly. In most cases, HTB patients have TB at

additional sites, but the primary tuberculosis focus has been absorbed

or overcome by fibrosis and calcification when HTB is found. Most

reports suggest that fever, abdominal pain, weight loss, and a loss of

appetite are common symptoms of HTB,[23-24] and a few patients present with jaundice.[25-26] In

our data, fever was the most common clinical symptom (48.2%), followed

by respiratory symptoms (27.5%) and abdominal pain (24.1%). A higher

number of respiratory symptoms than digestive tract symptoms reported

at the initial hospital visit may be related to the department the

patient attended, which is considered a referral bias. However, lung

localization, present in 86% of HTB patients, may cause respiratory

symptoms. Hepatosplenomegaly was the most common symptom of HTB.[27]

Unfortunately, hepatomegaly was not recorded in our data, and three

patients were thought to have splenic TB (one of whom had this

confirmed by a routine PET-CT examination). In our study, more than

half of the patients had elevated ESR and CRP and reduced albumin.

Tumour markers were within the normal range. Tuberculin tests showed

nine patients were strongly positive, six were moderately positive, and

five were negative. The r-interferon release test showed 20 patients

were positive and 9 negative (including 3 HIV patients). Therefore, a

negative tuberculin test result may not rule out TB in clinical

practice. In contrast, a positive r-interferon test should be

considered an alert for the possible presence of a TB infection, either

internal or external to the lungs.

All study patients showed

low-density liver lesions on abdominal CT scans. Several cases of mild

enhancement of the lesions' peripheral edges after contrast injection

have been reported in the literature.[28-29] The

study's CT and MRI results revealed that low-density shadows of

elliptical nodules were observed on CT scans in cases of serous HTB. A

progressive enhancement was observed between the artery and delayed

periods in enhanced scanning. The focal margin was blunt at the liver

parenchyma margin. The clinical findings for TB peritonitis and ovarian

cancer can overlap, leading to potential misdiagnoses.[30]

The

parenchymal HTB lesion was often surrounded by abnormal triangular

high-density shadows due to abnormal blood perfusion caused by an

inflammatory response. All TB nodules in the liver were clearer during

the portal phase, and enhancement was still visible around the lesion.

Their MRI often showed low T1WI and high T2WI and DW signals. However,

the ADC map showed a high signal. The enhanced scanning lesion had no

enhancement in the centre and a mild circular enhancement around it.

Intrahepatic bile duct TB is rare among HTB patients and was not found

in our study. Atypical HTB is characterized by irregular bile duct wall

thickening and expansion, enhanced scanning enhancement and delayed

enhancement, and diffuse punctate calcification of the bile duct wall.[31]

In some cases, the imaging sign appeared in liver abscesses, tumours,

and other lesions. In contrast, non-specific inflammation is not

evident in tumour lesions and could be considered an indirect sign of

HTB progression.[32] The enhanced scan portal stage

showed increased clarity around the lesions, and the delayed period

showed mild enhancement around the lesions, which are common

manifestations of the disease detected by MRI.

Study Limitations

The

present study was limited by the lack of Xpert MTB/RIF assay results,

cultures, and pathological specimens for some patients from the

clinical work used in this research. This omission may have led to some

patients with HTB remaining undiagnosed. Symptoms of the digestive

tract are frequently misdiagnosed as tumours or liver abscesses. Since

most patients refused a second biopsy procedure, imaging served as the

primary means of follow-up. Our experiments also have statistical

issues caused by small sample sizes due to the rarity of HTB.

Conclusion

In

conclusion, HTB is a rare disease with hidden clinical symptoms and

diverse imaging manifestations. Patients with pulmonary TB and an

existing history of TB or HIV infection should be made aware of the

possibility of HTB. Histopathology (diagnostic examination) showed

granuloma necrosis with giant cells. In all suspected cases diagnosed

by liver biopsy, Xpert MTB/RIF assay, and mycobacterium culture. AFP is

normal, so this test should be carried out whenever possible to

distinguish primary malignant liver tumours from HTB.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Ethics

approval and consent to participate. This study was conducted according

to the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by Wenzhou Central

Hospital. All participants signed an informed consent form for

inclusion in the study.

Availability of Data and Materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Competing Interests

The authors had no personal, financial, commercial, or academic conflicts of interest.

Funding

Supported by basic medical and health science and technology project in Wenzhou, Zhejiang Province in 2021 (No. Y20210844).

References

- Al Umairi R, Al Abri A, Kamona A. Tuberculosis (TB)

of the Porta Hepatis Presenting with Obstructive Jaundice Mimicking a

Malignant Biliary Tumor: A Case Report and Review of the Literature.

Case Rep Radiol. 2018;2018:5318197. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/5318197 PMid:30631628 PMCid:PMC6304509

- Bristowe

JS. On the connection between abscess of the liver and gastrointestinal

ulceration. Transac Pathol Soc London. 1858;9:241-252.

- Chien RN, Lin PY, Liaw YF. Hepatic tuberculosis: comparison of miliary and local form. Infection. 1995;23:9-12. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01710049 PMid:7744492

- Hickey

AJ, Gounder L, Moosa MY, Drain PK. A systematic review of hepatic

tuberculosis with considerations in human immunodeficiency virus

co-infection. BMC Infect Dis. 2015; 15:209. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-015-0944-6 PMid:25943103 PMCid:PMC4425874

- Li

W, Tang YF, Yang XF, Huang XY. Misidentification of hepatic

tuberculosis as cholangiocarcinoma: A case report. World J Clin Cases.

2021;9(31):9662-9669. https://doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i31.9662 PMid:34877304 PMCid:PMC8610856

- Long

X, Zhang L, Zhao JP, Cheng Q, Zhu P, Zhang BX, Chen XP. Surgical

treatment of primary hepatic tuberculosis. Journal of Abdominal

Surgery, 2020, 33(04): 278-281.

- Yang C,

Liu X, Ling W, Song B, Liu F. Primary isolated hepatic tuberculosis

mimicking small hepatocellular carcinoma: A case report. Medicine

(Baltimore). 2020;99(41):e22580. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000022580 PMid:33031307 PMCid:PMC7544287

- Kale

A, Patil PS, Chhanchure U, Deodhar K, Kulkarni S, Mehta S, Tandon S.

Hepatic tuberculosis masquerading as malignancy. Hepatol Int. 2021 Oct

23. doi: 10.1007/s12072-021-10257-9. Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-021-10257-9 PMid:34687434

- Tang SJ, Gao W. Clinical tuberculosis. Beijing: The People's Health Press, 2011.

- Garmpis

N, Damaskos C, Garmpi A, Liakea A, Mantas D. The Unexpected Diagnosis

of Hepatic Tuberculosis in an Immunocompetent Patient. Case Rep Surg.

2020;2020:7915084. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/7915084 PMid:33083083 PMCid:PMC7557907

- Freitas

M, Magalhães J, Marinho C, Cotter J. Looking beyond appearances: when

liver biopsy is the key for hepatic tuberculosis diagnosis. BMJ Case

Rep. 2020 May 5;13(5):e234491. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2020-234491 PMid:32376662 PMCid:PMC7228446

- Kohli

M, Schiller I, Dendukuri N, Yao M, Dheda K, Denkinger CM, Schumacher

SG, Steingart KR. Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra and Xpert MTB/RIF assays for

extrapulmonary tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance in adults.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Jan 15;1(1):CD012768. doi:

10.1002/14651858. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858

- Liu S. Analysis of diagnostic value of CT on serous hepatic tuberculosis. Guide of China Medicine, 2020,18(5):65.

- Wang QY. CT manifestations and diagnostic points of hepatic tuberculosis. Chinese Hepatology, 2016, 21(9):746-748.

- Lu

LQ, Li XW CT manifestations of parenchymal hepatic tuberculosis.

Chinese Imaging Journal of Integrated Traditional and Western Medicine,

2019, 17(3): 292-294.

- Hickey AJ, Gounder

L, Moosa MY, Drain PK. A systematic review of hepatic tuberculosis with

considerations in human immunodeficiency virus co-infection. BMC Infect

Dis. 2015;15:209. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-015-0944-6 PMid:25943103 PMCid:PMC4425874

- Zhang

L, Chen YP, Li Q. Research on the results of HIV infection and HBV,HCV,

TP and TB testing study. The Medical Forum, 2021, 25(26): 3792-3794.

- Forgione

A, Tovoli F, Ravaioli M, Renzulli M, Vasuri F, Piscaglia F, Granito A.

Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound LI-RADS LR-5 in Hepatic Tuberculosis: Case

Report and Literature Review of Imaging Features. Gastroenterology

Insights. 2021; 12(1):1-9. https://doi.org/10.3390/gastroent12010001

- Park

J. Primary hepatic tuberculosis mimicking intrahepatic

cholangiocarcinoma: report of two cases. Ann Surg Treat Res.

2015;89(2):98-101. https://doi.org/10.4174/astr.2015.89.2.98 PMid:26236700 PMCid:PMC4518037

- Bandyopadhyay S, Maity P. Hepatobiliary Tuberculosis. J Assoc Physicians India. 2013;61(6):404-7.

- Hung

Y-M, Huang N-C, Wang J-S, Wann S-R. Isolated hepatic tuberculosis

mimicking liver tumors in a dialysis patient. Hemodial Int.

2015;19:330-351. https://doi.org/10.1111/hdi.12205 PMid:25123829

- Wu

Z, Wang WL, Zhu Y, Cheng JW, Dong J, Li MX, Yu L, Lv Y, Wang B.

Diagnosis and treatment of hepatic tuberculosis: report of fve cases

and review of literature. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2013;6(9):845-850.

- Chong VH. Hepatobiliary tuberculosis: a review of presentations and outcomes. South Med J. 2008;101:356-361. https://doi.org/10.1097/SMJ.0b013e318164ddbb PMid:18360350

- Alvarez SZ. Hepatobilary tuberculosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;13(8):833-839. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1746.1998.tb00743.x PMid:9736180

- Desai

CS, Joshi AG, Abraham P, Desai DC, Deshpande RB, Bhaduri A, et al.

Hepatic tuberculosis in t absence of dissiminated abdominal

tuberculosis. Ann Hepatol. 2006;5(1):41-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1665-2681(19)32038-1

- Park

J. Primary hepatic tuberculosis mimicking intrahepatic

cholangiocarcinoma: report of two cases. Ann Surg Treat Res.

2015;89(2):98-101. https://doi.org/10.4174/astr.2015.89.2.98 PMid:26236700 PMCid:PMC4518037

- Bandyopadhyay S, Maity P. Hepatobiliary Tuberculosis. J Assoc Physicians India. 2013;61(6):404-7.

- Saha

SK, Zeng C, Li X, Mishra AK, Singh A, Silin D, et al. CT

characterization of hepatic tuberculosis. Radiol Infect Dis.

2017;4:143-149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrid.2017.09.001

- Levine C. Primary macronodular hepatic tuberculosis: US and CT appearances. Gastrointest Radiol. 1990;15:307-309. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01888805 PMid:2210202

- Arezzo

F, Cazzato G, Loizzi V, Ingravallo G, Chiang NJ. Peritoneal

Tuberculosis Mimicking Ovarian Cancer: Gynecologic Ultrasound

Evaluation with Histopathological Confirmation. Gastroenterology

Insights, 2021, 12(2): 278-282. https://doi.org/10.3390/gastroent12020024

- Abascal

J, Martin F, Abreu L, Pereira F, Herrera J, Ratia T, Menendez J.

Atypical hepatic tuberculosis presenting as obstructive jaundice. Am J

Gastroenterol, 1988, 83(10):1183-1186.

- Kang

Suhai, Xie Wei, Zhang Hui, Liu QW, Zhang Z. Imaging Diagnosis of

Hepatic Tuberculosis. Chinese Computed Medical Imaging, 2013, 19(3):

227-230.

[TOP]