Cristina Papayannidis¹,

Vincenzo Federico², Luana Fianchi³, Patrizia Pregno⁴, Novella

Pugliese⁵, Alessandra Romano⁶ and Federica Irene Grifoni⁷.

1 RCCS, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Bologna, Istituto di Ematologia “Seràgnoli”, Bologna Italy.

2 Haematology and Stem Cell Transplant Unit, Presidio Ospedaliero "Vito Fazzi", Lecce, Italy.

3

Department of Radiological Sciences, Radiotherapy, and Hematology,

Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli, IRCCS, Rome, Italy.

4

Hematology Division, Oncology and Hematology Department, Azienda

Ospedaliera Universitaria Città della Salute e della Scienza di Torino,

Torino, Italy

5 Department of Clinical Medicine and Surgery, Hematology Unit, Federico II University Medical School, Naples, Italy.

6 Division of Hematology, Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Policlinico-Vittorio Emanuele Catania, Catania, Italy.

7 Hematology Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, Italy.

Correspondence to:

Cristina Papayannidis. IRCCS, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di

Bologna, Istituto di Ematologia “Seràgnoli”, Bologna, Italy. E-mail:

cristina.papayannidis@unibo.it

Published: November 1, 2022

Received: May 10, 2022

Accepted: October 9, 2022

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2022, 14(1): e2022073 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2022.073

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Systemic

mastocytosis (SM) is a rare disease with a range of clinical

presentations, and the vast majority of patients have a KIT D816V

mutation that results in a gain of function. The multikinase/KIT

inhibitor midostaurin inhibits the D816V mutant and has a

well-established role in treating advanced SM. Even if considered the

standard of therapy, some open questions remain on optimizing

midostaurin management in daily practice. The current review presents

the opinions of a group of experts who met to discuss routine practice

using midostaurin in patients with advanced SM. The efficacy and safety

of midostaurin in Phase 2 trials are overviewed, followed by practical

guidance for optimal therapy management and adverse events during

therapy with midostaurin. Specific guidance is given for initiating

therapy and evaluating response with midostaurin as general assessment

and laboratory, instrumental, pathological, and molecular exams.

Special consideration is given to dose interruption, reduction, and

discontinuation of therapy, as well as adverse event management and

supportive therapy. Patients should be informed about possible side

effects and receive practical advice to avoid or limit them and

antiemetic prophylaxis so that therapy with midostaurin can continue as

long as clinical benefit is observed or until unacceptable toxicity

occurs. Lastly, considerations on the use of midostaurin during the

ongoing Covid-19 pandemic are made. The overall scope is to provide

guidance that can be useful in daily practice for clinicians using

midostaurin to treat patients with advanced SM.

|

Introduction

Mastocytosis is a rare disease characterized by a wide range of clinical presentations, symptoms, and prognosis.[1]

The symptoms of mastocytosis are due to the presence and proliferation

of neoplastic mast cells (MC) in one or more organs, with the skin

being a frequent site, followed by bone marrow.[1,2] Systemic mastocytosis (SM) is considered a hematological neoplasm.[1,2]

The WHO has classified SM into five major forms: indolent SM,

smoldering SM, SM with an associated hematopoietic neoplasm (SM-AHN),

aggressive SM (ASM), and mast cell leukemia (MCL).[3,4]

The latter three subtypes are grouped as advanced SM. Clinical findings

related to organ damage deriving from MC infiltration are called

C-findings and include cytopenia, liver-function abnormalities, weight

loss, ascites, and osteolytic bone lesions.[5] Aggressive SM is characterized by the presence of at least one C-finding.[5]

Due

partly to its rarity and diverse clinical presentations, SM can be

challenging to diagnose. Therefore, diagnosis generally requires that

either one major and one minor criterion are met or at least three

minor criteria are satisfied.[4] The major criterion

is the presence of multifocal dense infiltrates of mast cells (≥15 mast

cells in an aggregate) in the bone marrow and/or extracutaneous organs.

Minor criteria include: i) >25% of mast cells in the infiltrate are

spindle-shaped or have atypical morphology, or >25% of all mast

cells in bone marrow aspirate smears are immature or atypical; ii)

detection of KIT D816V mutation in bone marrow, blood, or another

extracutaneous organ; iii) mast cells in bone marrow, blood, or another

extracutaneous organ express CD25, with or without CD2; iv) persistent

serum tryptase >20 ng/ml (in case of an unrelated myeloid neoplasm,

this is not valid as an SM criterion).

It has been reported that the prevalence of SM is likely to be underestimated due to difficulties in diagnosis.[6] These difficulties may be linked to disease heterogeneity delaying the clinical suspicion[7]

and requiring a multidisciplinary approach in collaboration with (or

in) a center of excellence of mastocytosis involving hematologists,

rheumatologists, allergologists, and gastroenterologists.[8,9]

Indeed, a study from Germany reported that around one-third of patients

with advanced SM are either not diagnosed or misdiagnosed, and as such

greater attention should be given to tryptase levels, bone marrow

histology, and genetic analyses.[10]

Among the

genetic findings in SM, it has been known for some time that the vast

majority of patients have a KIT D816V mutation that results in a gain

of function and leads mast cells to uncontrolled proliferation.[11]

More recently, thanks to innovative molecular techniques, mutations in

TET2, SRSF2, ASXL1, RUNX1, JAK2, N/KRAS, CBL, and EZH2 have also been

found in a large proportion of patients with advanced disease.[12]

Many of them (involving SRSF2, ASXL1 and/or RUNX1) have been

demonstrated to correlate with a bad prognosis in terms of overall

survival and to be associated with adverse clinical features.[12,13] As far as treatment is concerned, Advanced SM frequently requires cytoreductive therapy[14]

that includes standard chemotherapy, immunomodulating agents, and

tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Among them, imatinib shows activity for

wild-type KIT but is not effective on the D816V mutation, which is

predominant in SM.[14,15]

In contrast, the

multikinase/KIT inhibitor midostaurin is able to inhibit the D816V

mutant, and its clinical utility in advanced SM has been confirmed,

leading the drug to FDA, EMA, and AIFA approval as monotherapy in

advanced SM patients.[15] As for chemotherapy or immunomodulating agents, in Italy, it is possible to employ subcutaneous cladribine by the law n° 648[16] or Interferon alfa-2b (IFN-a). In addition, peg-interferon alpha-2a or alpha-2b is suggested for better tolerability.[9,14]

However, compared to more traditional agents such as interferon or

cladribine, midostaurin can be considered a more modern and targeted

approach to treating advanced SM and is now widely used.[17]

New inhibitors are also becoming available, including avapritinib, a

selective inhibitor of D816V, approved by the U.S. Food and Drug

Administration (FDA) in June 2021 for patients with advanced SM and by

the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in March 2022 for patients with

advanced SM after at least one systemic therapy.[18,19]

Midostaurin is considered the standard approach for KIT inhibition in advanced SM.[18]

For SM-AHN patients, a comprehensive evaluation of both SM and AHN is

required to assess and correctly stage both diseases and evaluate for

which treatment priority is necessary, taking into particular

consideration the characteristics of the AHN component on a

case-by-case basis.[20] Indeed, an AHN such as

low-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) may not require immediate

treatment, while it would be needed if an aggressive AHN such as acute

myeloid leukemia (AML) is diagnosed. A more integrated approach,

covering the biological and clinical heterogeneity of advanced SM and

AHN-SM, may be more appropriate for treatment selection. However, the

debate is still open on this topic, and further studies are warranted.[21,17]

From

a practical perspective, some open questions remain regarding the use

of midostaurin in daily routine, and there is the need for better

prevention and management of adverse events to limit discontinuation or

dose reduction.

Management of therapy with midostaurin can also be complicated because some adverse events overlap with disease symptoms,[21] considering that the AHN component may also be responsible for the signs and symptoms.

The

aim of the current report is to present the opinions of a group of

experts who met to discuss clinical issues encountered in routine

practice regarding the use of midostaurin in patients with advanced SM.

In particular, following a brief overview of the efficacy and safety of

midostaurin, practical guidance is given for optimal therapy management

and adverse events to maximize the potential benefits of midostaurin.

In addition, a clinical case scenario will be used to provide a

practical example of how nausea can be managed. Finally, the group of

experts also presents considerations on the use of midostaurin during

the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic.

The overall scope is to provide

guidance that can be useful in daily practice for clinicians using

midostaurin to treat patients with advanced SM.

Midostaurin in Advanced SM

Phase 2 studies. In 2016, Gotlib et al. reported the results of an open-label phase 2 trial of midostaurin in 116 patients with advanced SM.[22]

In the primary efficacy population of 89 patients with

mastocytosis-related organ damage, the overall response rate according

to modified Valent response criteria[23] and Cheson criteria for transfusions[24,25]

criteria was 60%, and 45% of patients had a major response that was

independent of KIT mutation status. More recently, FDA and EMA assessed

the efficacy with a post-hoc exploratory analysis, per the

International Working Group - Myeloproliferative Neoplasms Research and

Treatment - European Competence Network on Mastocytosis (IWG-MRT-ECNM)

consensus criteria,[26] henceforth referred to as IWG criteria.[27,28]

Out of 116 patients, 113 had a C-finding as defined by IWG response

criteria (excluding ascites as a C-finding), and an overall response

rate of 28.3% was reported.[27,28] Nausea, vomiting,

and diarrhea were the most frequent adverse events, while neutropenia,

anemia, and thrombocytopenia were seen in 24-41% of patients.[22]

In addition, in 2018, DeAngelo et al. published the results of a phase

II study that enrolled 26 patients with advanced SM with an overall

response rate of 69% and no unexpected toxicity after a median

follow-up of 10 years.[29] Overall, midostaurin was considered to be effective and to have an acceptable safety profile.[29]

Initiating Therapy with Midostaurin in Advanced SM

Indications and recommended dosing for midostaurin.

Midostaurin was approved by FDA and EMA for newly diagnosed FLT3

mutation-positive acute myeloid leukemia in combination with standard

daunorubicin and cytarabine induction and high-dose cytarabine

consolidation chemotherapy for patients in complete response as

single-agent maintenance therapy, and as monotherapy for the treatment

of adult patients with aggressive SM, SM-AHN, or mast cell leukemia

(MCL). Prophylactic antiemetics can be considered in accordance with

local practice and patient tolerance. In aggressive SM, SM- AHN, and

MCL, the recommended starting dose is 100 mg BID with food. No dose

adjustments are needed in patients ≥65 years of age, with mild to

moderate renal impairment or mild to moderate hepatic impairment.[28]

General considerations.

Before initiating therapy with midostaurin, some preliminary

assessments may be recommended, even if many of the exams deemed

mandatory may have already been performed as part of a proper

diagnostic work-up. In women of childbearing age, a pregnancy test

within seven days before starting treatment is considered compulsory,

considering the potential risk of harm to the fetus. In addition, women

using hormonal contraceptives should also add a barrier method of

contraception as it is currently unknown whether midostaurin may reduce

the effectiveness of hormonal contraceptives. Women should discontinue

breastfeeding during treatment. Complete prescription knowledge is

needed since concomitant administration with strong CYP3A inducers is

contraindicated, and caution is required in combination with strong

inhibitors of CYP3A4. For cases where a concomitant CYP3A4 inhibitor is

strongly warranted from a clinical standpoint, midostaurin is not

forbidden, but frequent monitoring is required (i.e., ECG, liver tests,

etc.). Patients should also be advised to take midostaurin with food

since it increases midostaurin’s absorption and reduces its peak

concentration (Cmax).[28] Administration of food may also help to limit some adverse events.

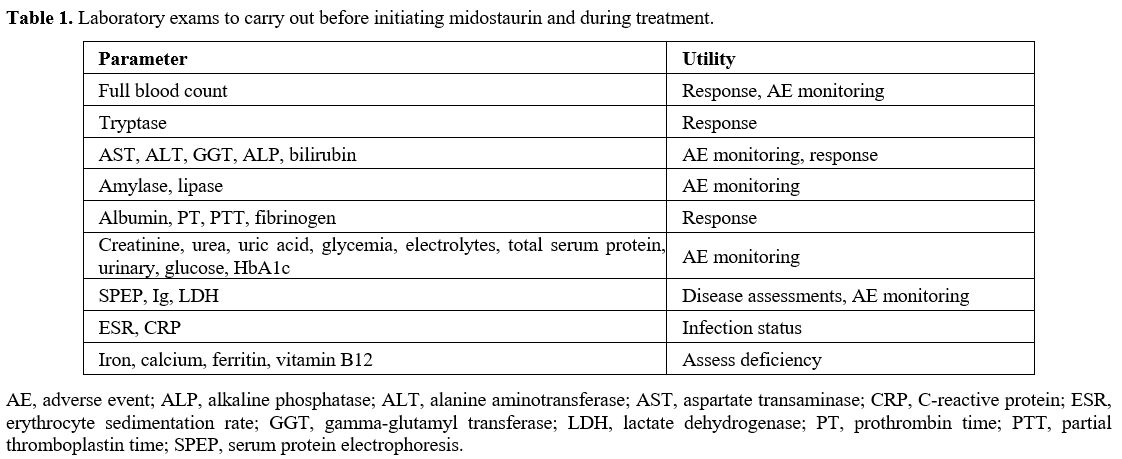

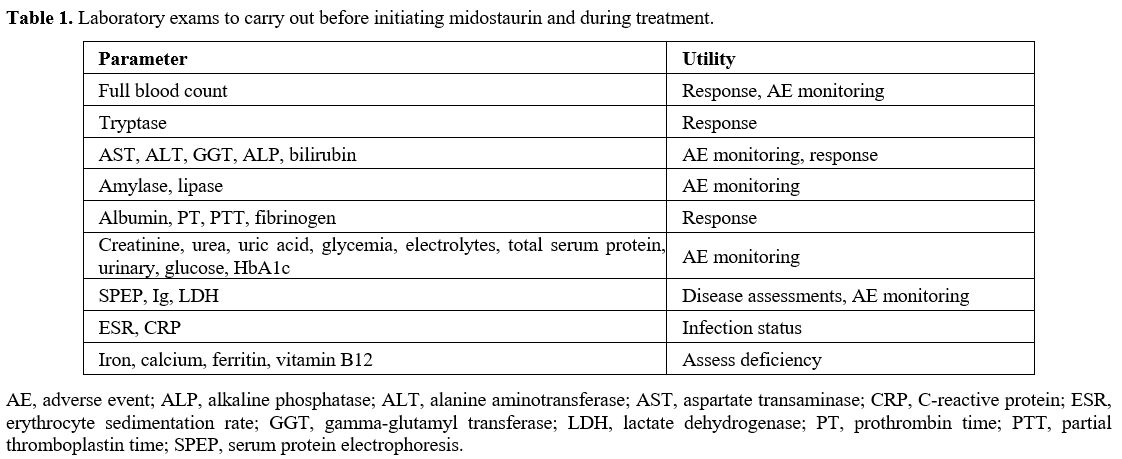

Laboratory exams.

The expert panel recommended several laboratory exams before initiating

therapy with midostaurin to have pre-treatment reference values that

can be used to monitor both toxicity and response to therapy (Table 1).

In particular, full blood count, liver enzymes, creatinine, amylase,

and lipase should be obtained, in addition to baseline tryptase.

|

Table 1. Laboratory exams to carry out before initiating midostaurin and during treatment. |

Additionally,

albumin and total serum protein clotting-related factors (anti-thrombin

III, prothrombin, aPTT, and fibrinogen) should also be assessed.

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein should be

used to exclude infections. It was also considered important to

evaluate iron levels, ferritin, folate, and B12 levels to rule out

deficiency anemia or treat it as needed.

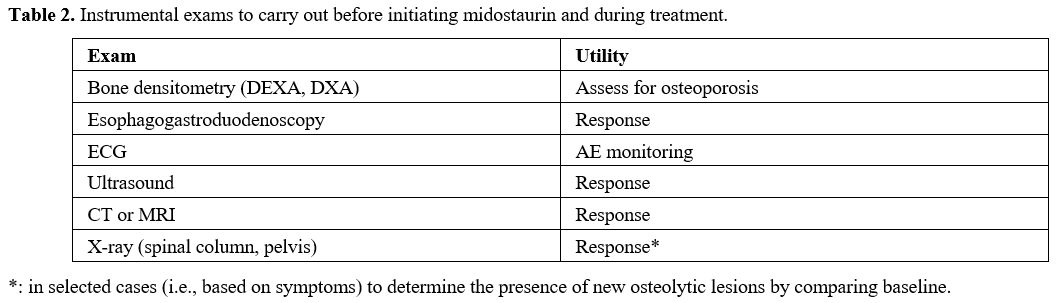

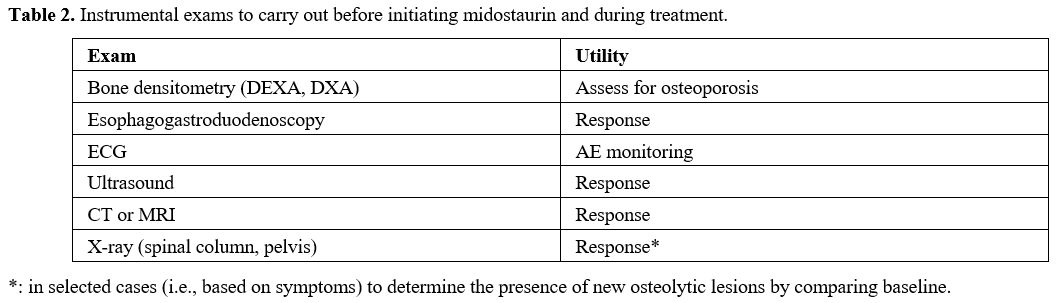

Instrumental exams. Several instrumental exams should be highly recommended (Table 2).

Since interstitial lung disease has been reported with midostaurin, it

is important to have a baseline chest X-ray, which may be repeated

during follow-up if required by clinical alterations. An

Electrocardiogram (ECG) with an evaluation of QTc should always be

performed at baseline to exclude the absence of concomitant pathologies

at baseline and since QTc prolongation has been reported in

midostaurin-treated patients, especially if midostaurin is taken

concurrently with medicinal products that can prolong the QT interval.

If a patient takes midostaurin concurrently with other medications that

can prolong the QT interval, physicians should consider regularly

scheduled assessments by ECG.[30] However, the

expert panel suggested that, for accurate management, ECG should be

carried out every three months during the first year of treatment to

evaluate for toxicity, even in the absence of QT prolongation.

|

Table 2. Instrumental exams to carry out before initiating midostaurin and during treatment. |

In

order to assess skeletal disease involvement, which is frequently

observed in advanced systemic mastocytosis (AdvSM) patients, a

whole-body radiographic study should be carried out.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy

(EGD) and colonoscopy can be considered optional and must be performed

only in patients with gastrointestinal signs to have a diagnostic

confirmation of gastrointestinal involvement. EGD and colonoscopy can

also help evaluate the response to therapy in these patients.

Pathology and molecular assessments.

The pathologist, with strong expertise in hematological diseases, plays

a relevant role in the management of SM as, in practice, morphological

examination of bone marrow (both biopsy and aspiration) is required for

a right diagnosis and may also detect an associated hematologic

neoplasm, if present.[5] Moreover, in the context of

SM-AHN, not only morphological but also cytogenetic and molecular

analyses are of particular value.[5]

Dialogue

between experienced pathologists and clinicians is strongly recommended

for optimal diagnosis and management of SM patients, particularly for

SM-AHN cases, because clinical data and laboratory alterations should

be matched. Biopsy of affected disease sites, such as gastrointestinal

mucosa or localized bone lesions, is also possible, but it is

infrequently pursued.[5] Lastly, it is recommended

that diagnosis and subclassification of SM and the potential AHN

component be carried out in dedicated reference centers to avoid

misclassification and allow adequate diagnosis.[31]

Molecular testing, particularly KIT D816V using highly sensitive and quantitative PCR techniques such as digital PCR[32]

and mast cell immunophenotyping by flow cytometry and/or

immunohistochemistry are mandatory. Next-generation sequencing (NGS)

can be considered in specialized centers for full mutational screening (TET2; SRSF2; ASXL1; RUXN1), and in selected cases, if KIT D816V

with ASO-qPCR and PNA-mediated PCR is negative, as this may have

prognostic value. Indeed, when concomitant hematological neoplasia is

present, NGS is required to obtain a complete characterization of the

disease and to have detailed information on staging at baseline. If

eosinophilia is present, the pathologist should screen for FIP1L1-PDGFRA

molecular rearrangement. Cytogenetic assessment is important in

assessing for the presence of other hematological neoplasms. The

pathologist is responsible for the collection and archival of tissue

samples that will be needed for future analyses in accordance with the

hematologist.

From a therapeutic standpoint, bone marrow biopsy and aspiration with morphology, flow-cytometry, and quantification of KIT allele burden also have a role in monitoring response to the therapy; however, there is no established standard at present.[33]

Therapy, Follow-Up and Evaluation of Response

With

midostaurin, based on clinical trials and real-life experiences, a

rapid response is seen in many patients when given in the first line.[22]

As advanced SM is a highly heterogeneous disease in terms of clinical

manifestations and symptoms, timing and modalities of follow-up should

be individualized and based on the characteristics of the disease and

patient. While tryptase is a fundamental indicator of response, in a

real setting, many exams are needed to monitor the patient’s response

to therapy, as detailed below. Treatment should be continued as long as

clinical benefit is observed or until unacceptable toxicity occurs.[28]

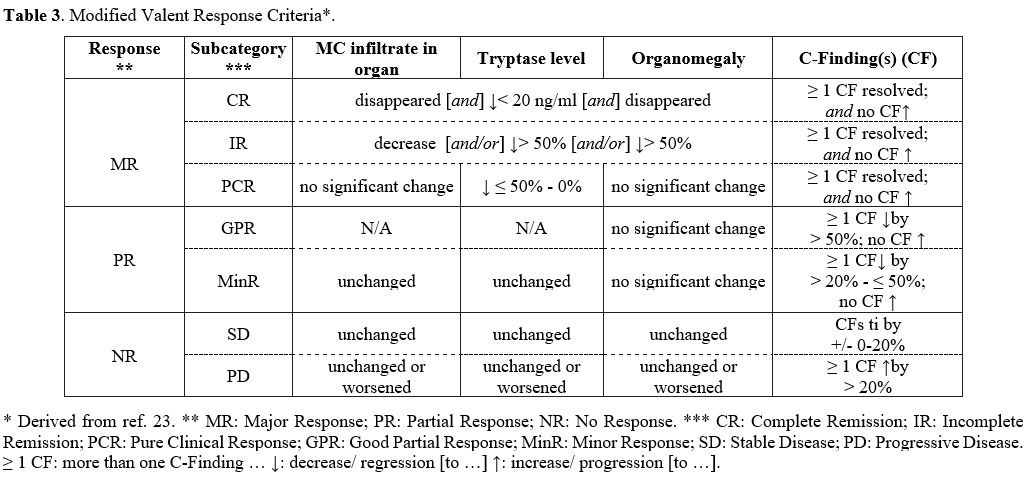

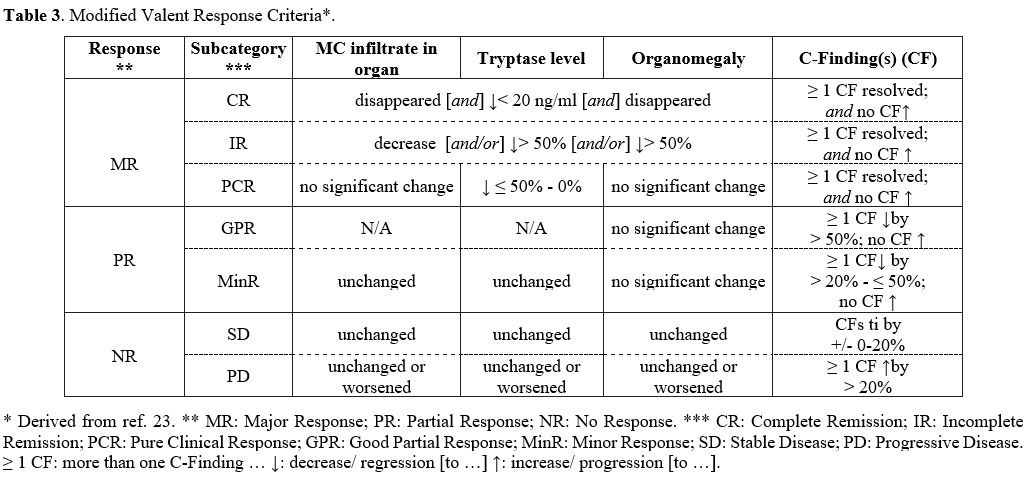

Response criteria.

Defining global response criteria for mastocytosis remains a challenge

due to the diverse clinical presentations of this condition.[34]

Criteria for evaluation of response were first published in 2003 by

Valent et al. and were subsequently modified in 2013 by IWG-MRT and

ECNM.[26,35,36] The IWG-MRT-ECNM criteria are employed mostly for clinical trials and are mainly based on a TKI approach.[26]

Additionally, in this context, new response criteria for advanced SM have been recently proposed[37] following a modular approach and creating a tiered response evaluation of pathologic, molecular, and clinical responses.[38]

While

the IWG-MRT-ECNM criteria and the latest approach mentioned are

particularly relevant in the context of clinical trials and to assess

response if an AHN component is present, in daily clinical practice,

the response is still usually monitored using C-findings, and is

broadly classified as a major response, partial response, clinical

improvement and no response.[35] A version of these

criteria, known as “modified Valent criteria”, was used to assess

response to midostaurin treatment within clinical trials[22,23] and is described hereafter and in Table 3.

A major response is designated as the resolution of one or more

C-findings and further subcategorized as complete (no organ

infiltrates, tryptase < 20 ng/ml, no organomegaly), incomplete

(>50% decrease in organ infiltrates, tryptase, and organomegaly), or

pure clinical remission (no significant change in organ infiltrates and

organomegaly, and tryptase decreased by 0-50%). In addition, a partial

response is considered good when one or more C-findings have improved

by more than 50%, and minor when improved by >20 to ≤50%. Lastly,

no response is considered when one or more C-findings either show a

constant range or have worsened by >20%. Unfortunately, the selected

criteria for response evaluation are not always exhaustive for

mastocytosis overall.[34]

|

Table 3. Modified Valent Response Criteria*. |

Laboratory, instrumental, and pathology exams.

Among blood and laboratory tests, full blood count, tryptase, albumin,

PT, PTT, alkaline phosphatase, and fibrinogen are useful to monitor

response to therapy (the latest if baseline values are abnormal).

Bone

marrow biopsy and aspiration with morphology, flow-cytometry, and the

quantifications of KIT allele burden also have a role in monitoring

response to therapy. Relative reduction by ≥25% in the expressed KIT

D816V allele has been associated with improved prognosis.[39]

However, the experts held that while evaluation of allelic burden is

useful, there is still no consensus on the timing and method to use. It

should also be kept in mind that cytogenetic alterations have a

prognostic impact on overall survival (OS).[40]

Concerning

instrumental exams, ultrasound, CT, or MRI can be used to assess

organomegaly and have an important role in monitoring its reduction.[13]

In addition, only in selected cases (i.e., based on symptoms) can

skeletal X-rays be used to determine the presence of new osteolytic

lesions by comparing images taken before initiating therapy, as no

current evidence that midostaurin improves bone disease in SM has been

reported to date.[41]

The expert panel agreed

that laboratory and clinical evaluation should be monitored at baseline

and at least at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months from the start of therapy.

However, the schedule may vary depending on the baseline severity of

blood counts and the degree of emergent cytopenia.[30]

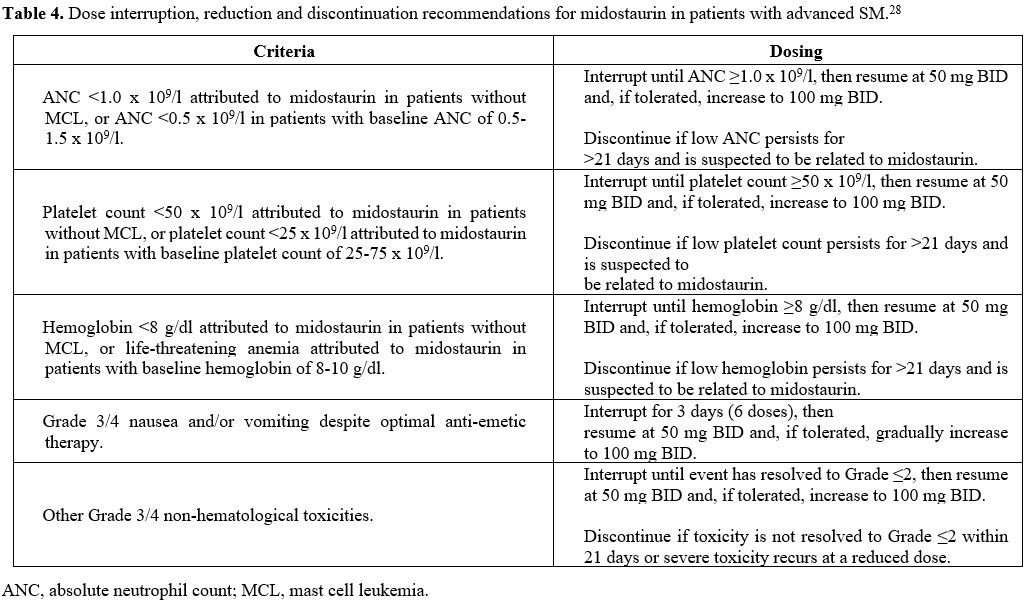

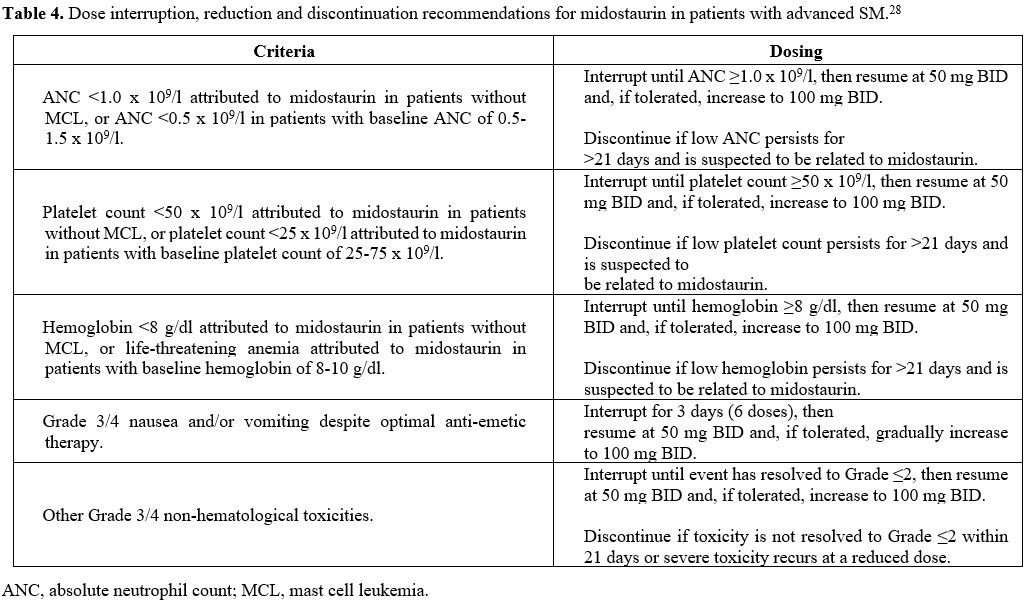

Dose interruption, reduction, and discontinuation.

In advanced SM patients who receive midostaurin, treatment-related

adverse events (AEs) are often difficult to distinguish from

disease-related symptoms, which can lead physicians to prematurely

discontinue drug administration or inadequately reduce the dosage in

patients who might have benefitted from continued therapy. Therefore,

it is important to assess the criteria to identify and manage AEs, in

order to maximize the potential benefits of midostaurin.

Dose

interruption and reduction during therapy can be considered in several

scenarios. These include reductions in absolute neutrophil count,

platelet count, hemoglobin, Grade 3/4 nausea and vomiting, and other

Grade 3/4 non-hematological toxicities such as diarrhea (Table 4).

|

Table 4. Dose interruption, reduction and discontinuation recommendations for midostaurin in patients with advanced SM.[28] |

In the case of hematological toxicity at the grade specified in Table 4, the dose is interrupted until the ANC, platelet count, or hemoglobin level improves.[28] Midostaurin is then resumed at 50 mg BID and subsequently increased to 100 mg BID.[28] Midostaurin should be discontinued if low levels of ANC, platelet count, or hemoglobin persist for >21 days.[28]

Midostaurin can cause nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.[28]

Patients should be reminded to take midostaurin with food, and the soft

capsules should not be chewed but swallowed whole.[42] In the case of

Grade 3/4 nausea and vomiting, midostaurin should be interrupted

for three days (6 doses) and then resumed at 50 mg BID; if tolerated,

the dose can be gradually increased to 100 mg BID. For other Grade 3/4

non-hematological toxicities, midostaurin should be interrupted until

the event has resolved to grade ≤2 and then resumed at 50 mg BID; if

tolerated, the dose can be increased to 100 mg BID. Midostaurin should

be discontinued if toxicity is not resolved to Grade ≤2 within 21 days

or if severe toxicity recurs at the reduced dose.

As pulmonary toxicity has occurred in patients treated with midostaurin monotherapy or in combination with chemotherapy,[28]

patients should be counseled about possible signs and symptoms such as

new or worsening cough and dyspnea. In addition, Midostaurin should be

discontinued in patients who experience pulmonary symptoms indicative

of interstitial lung disease or pneumonitis that are ≥ Grade 3 (NCI

CTCAE).[28]

Adverse event management and supportive therapy.

Midostaurin demonstrated clinical benefit in advanced SM with a high

rate of response accompanied by reduced mast cell infiltration of bone

marrow and decreased serum tryptase levels.[43] More recently, it has been shown that midostaurin improves the quality of life and SM-associated symptoms.[44]

Moreover, a pooled analysis of the two phase-2 studies found that

midostaurin reported an increase of about two-fold in OS versus

historical controls from a patient registry (42.6 vs. 24.0 months,

respectively). Propensity scoring was used for supportive analyses to

match patients in the registry and provided consistent results (hazard

ratio (HR)=0.381 [95% CI, 0.169-0.960]; P=.101).[45]

To help patients optimize midostaurin’s potential benefits, it is thus

important to utilize strategies to minimize treatment-related adverse

events such as nausea and vomiting. Indeed, the panel noted that these

latter events are among the main adverse events that lead to

discontinuation of therapy and dose reduction in daily practice.

Therefore, proper management of hematologic and nonhematologic adverse

events, including diarrhea, may help to avoid unnecessary dose

reduction, interruption, or discontinuation of midostaurin in patients

who might otherwise benefit from the continuation of therapy.[30]

Management of nausea and vomiting.

As mentioned, patients taking midostaurin are frequently expected to

experience nausea. However, the expert panel noted that these symptoms

might improve over time, particularly when managed correctly. It has

also been observed that patients typically experience nausea to a far

lesser extent after the evening dose compared to the morning dose.[26]

In particular, antiemetic prophylaxis should be administered as needed,

and patients should be given practical diet advice and reminded to take

midostaurin with food. Some practical tips that can be used to avoid

nausea and vomiting include opening the blister pack away from the face

and/or applying a strong-smelling ointment under the nose.[42] In addition, any comedications, which may cause nausea and vomiting, should be carefully evaluated.[42]

Moreover, in this context, the expert panel highlighted the usefulness

for patients to keep a food and symptoms diary that, beyond monitoring

possible trigger foods, can help to identify whether consumed products

are linked to an increase in nausea and/or vomiting. Of note, when

prescribing midostaurin with other medications that can prolong the QT

interval (e.g., some of the most commonly used antiemetics, such as

ondansetron or granisetron), physicians should consider regularly

scheduled assessments by ECG.

The group of experts referred that

they all used ondansetron in their centers; a dose of 8 mg taken 1 hour

prior to midostaurin has been previously suggested.[30]

Some of the experts referred that they also used granisetron

transdermal plasters to avoid further increasing the number of tablets

to be taken, with changes every five days, as described in the

real-life case scenario. However, ondansetron can be useful when

initiating therapy during the first week since the patch takes longer

to demonstrate full efficacy. As highlighted by the panel, adequate

supportive therapy is undoubtedly helpful in mitigating

midostaurin-related nausea and vomiting and is associated with good

adherence to therapy.

Case Scenario and Management of Nausea

This

female patient was born in 1975. Her symptoms began in 2007, and she

was diagnosed with aggressive SM in January 2016. The patient presents

with a high disease burden with a BM biopsy showing > 30%

infiltration of MC as focal, dense aggregates and serum tryptase level

> 200 ng/ml, skeletal involvement, and malabsorption with weight

loss due to MC infiltrates (both as C-findings). Midostaurin was

started at 100 mg BID in December 2018 as second-line therapy following

interferon. The patient experienced Grade 3/4 nausea during the first

months of therapy that was not resolved with ondansetron. The dose of

midostaurin was thus reduced to 50 mg BID. Using a granisetron plaster

allowed for resolution of nausea, and consequently, the dose of

midostaurin was successfully increased to 100 mg BID. Treatment at 100

mg BID has been ongoing for 28 months, and the patient has not

experienced other adverse events.

Management of diarrhea.

Among nonhematologic toxicities, diarrhea was reported in 54% of

patients treated with midostaurin.[22]However, gastrointestinal (GI)

symptoms are commonly present in SM patients due to the release of MC

mediators and, in advanced forms, by MC infiltration of the gut causing

malabsorption.[46] Indeed, 33-45% of patients reported diarrhea as a manifestation of their disease.[47,48]

In addition, in patients treated with midostaurin, substantial

improvements in MC mediator–related symptoms, including diarrhea, were

reported.[44] Therefore, it is crucial to distinguish between disease-

and midostaurin-related diarrhea. In this context, some clinical

“clues” were described to be helpful:[30] appropriate

therapy (i.e., histamine H2 receptor blockers or cromolyn sodium) may

offer relief to disease-related diarrhea; in case of no response, it is

more probable that the diarrhea is related to midostaurin.

Furthermore,

a temporal increase in the frequency and/or severity of diarrhea

compared to baseline disease-related or new onset of diarrhea with the

initiation of midostaurin may also favor the correlation with this

agent. In these cases, a dose reduction of midostaurin or concomitant

use of antidiarrheal agents (e.g., diphenoxylate/atropine, loperamide)

are potential options for diarrhea management. In general, determining

the bowel involvement by SM (through endoscopy and/or colonoscopy with

biopsies and staining for CD117, tryptase, and CD25) may be useful.[30]

Finally, as already suggested for nausea and vomiting management, diet

monitoring with a food and symptoms diary may help to identify

potential food intolerance as a source of GI symptoms.

Management of cytopenia.

Cytopenia is not uncommon in patients receiving midostaurin, but it may

sometimes be difficult to understand if the cytopenia is related to the

treatment or the disease. If the serum tryptase level and bone-marrow

mast cell infiltration realistically compare with the degree of

cytopenia, then it is likely that the low blood counts are related to

the disease itself.[30] However, if there is only a

small amount of mast cell infiltration in bone marrow, an associated

hematological neoplasm may account for cytopenia. On the other hand,

cytopenias may be determined by midostaurin if other disease markers

(e.g., bone marrow MC burden, serum tryptase level, organ damage)

improve, but cytopenia does not improve or even worsens upon treatment

start.[30] Therefore, monitoring complete blood count

every 1-2 weeks during the first 2 months of therapy is generally

recommended, with monitoring intervals after that determined

individually.[30] Both red blood cell and platelet

transfusions should be given when clinically warranted; also, in case

of anemia, erythropoiesis-stimulating agents may be considered, even

though this was not evaluated in clinical trials.[30] In addition, patients should be given supportive care with G-CSF and antibiotics according to local practice recommendations.[30]

The steps to take in terms of dose reduction and discontinuation of

midostaurin for cytopenia (neutropenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia)

are described in Table 4.

Other. Hyperglycemia is the most frequent non-hematological laboratory abnormality found in up to 94% of patients.[28]

Since diabetes is a potential risk factor for cardiovascular disease,

in the event of hyperglycemia, the patient should be evaluated for

glucose intolerance and referred to a diabetologist. In addition,

patients should receive education on cardiac risk factors optimization,

while oral hypoglycemic agents or insulin may be considered if

clinically indicated.[30] No midostaurin dose adjustments have been required for patients with hyperglycemia;[30] however, dose interruption and reduction can be considered for Grade 3/4 non-hematological toxicities as described in Table 4 and/or on a case-by-case basis. Hyperlipasemia is also a frequent finding, usually asymptomatic.[29,30]

Therefore, lipase should be monitored, and if elevated, patients should

be followed up, given supportive care as clinically indicated, and

advised to avoid all consumption of alcohol. No midostaurin dose

adjustments were reported as necessary;[30] however, dose interruption and reductions should be made according to Table 4

or on a case-by-case basis. Skin rash is also very common, affecting

more than 10% of patients; in these cases, topical corticosteroids and

H1 antihistamines may be administered if needed.[30]

Dose modifications for these alterations should be made on a

case-by-case basis. In studies with advanced SM, photosensitivity was

reported in a small analysis of 28 patients in a transitory-use

authorization program in France[49] and as in a case report,[50] but not in other studies.[28] If there is concern about photosensitivity, patients can be advised to wear sunscreen and suitable protective clothing.

Management of Midostaurin in SM During the Covid-19 Era and Vaccination

The

ongoing Covid-19 pandemic has severely disrupted healthcare systems

worldwide, but now the situation is slowly returning to normality.

While advanced SM does not appear to place patients at greater risk of

SARS-CoV-2 infection or severe Covid-19 in itself, many patients have

many comorbidities or other characteristics that may predispose them to

severe Covid-19, for example, male sex, age >65 years, type 2

diabetes, and obesity.[51]

General recommendations include avoiding any situation associated with increased risk of acquiring or transmitting infection.[51]

In the case of Covid-19 infection, it has also been suggested that

immunosuppressants, aggressive cytoreductive therapy, and drugs that

deplete lymphocytes should be avoided or postponed if possible (e.g.,

rituximab, alemtuzumab, cladribine).[51]

However,

treatment with anti-mediator drugs, bisphosphonates, and inhibitors of

KIT kinase, such as midostaurin, should be continued, which has been

done in clinics in Italy. The indications for interruption and

discontinuation of therapy should be based on the best clinical

judgment. Moreover, during the pandemic, patients with SM were followed

according to the recommendations of the Italian Society for Hematology

and the Italian Group for Bone Marrow Transplantation.[52]

At

the end of 2020, effective COVID-19 vaccinations were developed and

made available. Since then, some reports on the use of vaccines against

SARS-CoV-2 in patients with SM have been published.[53,54]

The authors suggested that this provides evidence that the vaccine is

safe in patients with mastocytosis. These reports, together with the

current knowledge of the safety profile of COVID-19 vaccinations, were

followed by the publication of the ECNM and American Initiative in Mast

Cell Disease (AIM) recommendations on COVID-19 Vaccination in

mastocytosis patients.[55] In summary, the panel of

experts acknowledges that severe adverse reactions from COVID-19

Vaccination are rare, even in patients with mastocytosis. Therefore,

the general use of COVID-19 Vaccination in these patients is

recommended. The only well-established exception is known or suspected

allergy against a vaccine constituent. However, it is suggested to

consider some safety measures, including premedication and

postvaccination observation, in all patients with mastocytosis,

depending on the individual risk. Indeed, guidance from the expert

panel results in a stratification of risk and recognizes three

categories of patients at low, mild, and high risk of Vaccination which

will require differentiated safety measures. These recommendations are

based on expert opinion and have not been evaluated with regard to

effectiveness.

Conclusions

Tyrosine

kinase inhibitors such as midostaurin have revolutionized the treatment

of advanced SM. Notwithstanding, treatment of advanced SM with

midostaurin can add a further challenge to disease management, which is

complex and requires the involvement of a multidisciplinary team

(hematologists, pathologists, allergologists, dermatologists,

rheumatologists, and gastroenterologists), and a multitude of

laboratory, instrumental, and pathological exams prior to initiating

therapy. Most tests are required as part of proper diagnostic work-up

and during follow-up to monitor therapeutic response and emergent

toxicities. However, the timing and modalities of follow-up may vary

based on individual patient and disease characteristics. To achieve the

most out of treatment with midostaurin in the advanced SM population,

prescribers must be aware of its side effect profile and be able to

recognize disease-related symptoms versus treatment-related adverse

events, in particular nausea and vomiting. As the expert panel noted,

optimal management of AEs may limit premature discontinuation and

improper dose reduction of midostaurin and maximize the potential

benefit of this treatment. With the intent to further refine a

personalized approach in advanced SM, new treatments are developing and

will extend the available therapeutic opportunities. Future research

should also focus on combining KIT-targeting agents with AHN-directed

agents since SM-AHN still represents an unresolved challenge. New

approaches need to be able to address the remaining unmet needs in

advanced SM.

Authors’ Contributions

Conceptualization

and design: all; Writing (original draft): all; Writing (review and

editing): CP, VF, FIG. All authors read and approved the final version

of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

CP

reports to have participated in Advisory Boards for Novartis and

AbbVie, outside the submitted work. LF has nothing to disclose. VF

reports to have participated in an Advisory Board for Amgen, outside

the submitted work. FIG has nothing to disclose. NP has nothing to

disclose. PP reports payment or honoraria as a speaker and for Advisory

Boards from Novartis Italia, outside the submitted work. AR reports

consulting fees from Novartis and to have participated on a Data Safety

Monitoring Board/Advisory Board for Novartis, outside the submitted

work.

Acknowledgements

The

authors thank Patrick Moore, PhD for medical writing assistance on

behalf of Health Publishing & Services srl, which was funded by

Novartis Farma, Origgio, Italy in accordance with Good Publication

Practice (GPP3) guidelines.

References

- Radia DH, Green A, Oni C and Moonim M. The clinical

and pathological panoply of systemic mastocytosis. Br J Haematol.

2020;188:623-640. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.16288 PMid:31985050

- Horny HP, Sotlar K and Valent P. Mastocytosis: state of the art. Pathobiology. 2007;74:121-132. https://doi.org/10.1159/000101711 PMid:17587883

- Valent

P, Akin C and Metcalfe DD. Mastocytosis: 2016 updated WHO

classification and novel emerging treatment concepts. Blood.

2017;129:1420-1427. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2016-09-731893 PMid:28031180 PMCid:PMC5356454

- Swerdlow

SH. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid

tissues 4th ed (revised). IARC Press; Lyon, France. 2017.

- Pardanani

A. Systemic mastocytosis in adults: 2021 Update on diagnosis, risk

stratification and management. Am J Hematol. 2021;96:508-525. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.26118 PMid:33524167

- Martelli

M, Monaldi C, De Santis S, Bruno S, Mancini M, Cavo M and Soverini S.

Recent Advances in the Molecular Biology of Systemic Mastocytosis:

Implications for Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Therapy. Int J Mol Sci.

2020;21:3987. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21113987 PMid:32498255 PMCid:PMC7312790

- Hermans

MAW, Rietveld MJA, van Laar JAM, Dalm VASH, Verburg M, Pasmans SGMA,

van Wijk RG, van Hagen PM and van Daele PLA. Systemic mastocytosis: A

cohort study on clinical characteristics of 136 patients in a large

tertiary centre. European Journal of Internal Medicine.

2016;30:25-30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2016.01.005 PMid:26809706

- Valent

P, Akin C, Gleixner KV Sperr WR, Reiter A, Arock M and Triggiani M.

Multidisciplinary Challenges in Mastocytosis and How to Address with

Personalized Medicine Approaches. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;

20(12):2976. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20122976 PMid:31216696 PMCid:PMC6627900

- Zanotti

R, Tanasi I, Crosera L, Bonifacio M, Schena D, Orsolini G, Mastropaolo

F, Olivieri E and Bonadonna P. Systemic mastocytosis: multidisciplinary

approach. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2021;13(1):e2021068. https://doi.org/10.4084/MJHID.2021.068 PMid:34804442 PMCid:PMC8577553

- Schwaab

J, Cabral do OHN, Naumann N, Jawhar M, Weiss C, Metzgeroth G, Schmid A,

Lübke J, Reiter L, Fabarius A, Cross NCP, Sotlar K, Valent P,

Kluin-Nelemans HC, Hofmann WK, Horny HP, Panse J and Reiter A.

Importance of Adequate Diagnostic Workup for Correct Diagnosis of

Advanced Systemic Mastocytosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract.

2020;8:3121-3127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2020.05.005 PMid:32422371

- Nagata

H, Worobec AS, Oh CK, Chowdhury BA, Tannenbaum S, Suzuki Y and Metcalfe

DD. Identification of a point mutation in the catalytic domain of the

protooncogene c-kit in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients

who have mastocytosis with an associated hematologic disorder. Proc

Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:10560-10564. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.92.23.10560 PMid:7479840 PMCid:PMC40651

- Jawhar

M, Schwaab J, Schnittger S, Meggendorfer M, Pfirrmann M, Sotlar K,

Horny HP, Metzgeroth G, Kluger S, Naumann N, Haferlach C, Haferlach T,

Valent P, Hofmann WK, Fabarius A, Cross NCP, Reiter A. Additional

mutations in SRSF2, ASXL1 and/or RUNX1 identify a high-risk group of

patients with KIT D816V(+) advanced systemic mastocytosis. Leukemia.

2016;30:136-143. https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2015.284 PMid:26464169

- Jawhar

M, Schwaab J, Hausmann D, Clemens J, Naumann N, Henzler T, Horny HP,

Sotlar K, Schoenberg SO, Cross NCP, Fabarius A, Hofmann WK, Valent P,

Metzgeroth G and Reiter A. Splenomegaly, elevated alkaline phosphatase

and mutations in the SRSF2/ASXL1/RUNX1 gene panel are strong adverse

prognostic markers in patients with systemic mastocytosis. Leukemia

2016;30:2342-2350. https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2016.190 PMid:27416984

- Pardanani

A. Systemic Mastocytosis in Adults: 2021 Update on Diagnosis, Risk

Stratification and Management. Am J Hematol. 2021;96:508-525. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.26118 PMid:33524167

- Gilreath

JA, Tchertanov L and Deininger MW. Novel approaches to treating

advanced systemic mastocytosis. Clin Pharmacol. 2019;11:77-92. https://doi.org/10.2147/CPAA.S206615 PMid:31372066 PMCid:PMC6630092

- Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco (AIFA). Legge n.648/1996. https://www.aifa.gov.it/legge-648-96

- Mannelli

F. Catching the clinical and biological diversity for an appropriate

therapeutic approach in systemic mastocytosis. Ann Hematol.

2021;100:337-344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-020-04323-9 PMid:33156374 PMCid:PMC7646220

- Piris-Villaespesa

M and Alvarez-Twose I. Systemic Mastocytosis: Following the Tyrosine

Kinase Inhibition Roadmap. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:443. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2020.00443 PMid:32346366 PMCid:PMC7171446

- Ayvakyt. Summary of Product Characteristic. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/ayvakyt-epar-product-information_en.pdf (Accessed 26 June, 2022)

- Gotlib

J, Gerds AT, Bose P, Castells MC, Deininger MW, Gojo I, Gundabolu K,

Hobbs G, Jamieson C, McMahon B, Mohan SR, Oehler V, Oh S, Padron E,

Pancari P, Papadantonakis N, Pardanani A, Podoltsev V, Rampal R,

Ranheim E, Rein L, Snyder DS, Stein BL, Talpaz M, Thota S, Wadleigh M,

Walsh K, Bergman MA and Sundar H. Systemic Mastocytosis, Version

2.2019, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr

Canc Netw. 2018;16:1500-1537. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2018.0088 PMid:30545997

- Reiter

A, George TI and Gotlib J. New developments in diagnosis,

prognostication, and treatment of advanced systemic mastocytosis.

Blood. 2020;135:1365-1376. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2019000932 PMid:32106312

- Gotlib

J, Kluin-Nelemans HC, George TI, Akin C, Sotlar K, Hermine O, Awan FT,

Hexner E, Mauro MJ, Sternberg DW, Villeneuve M, Huntsman Labed A,

Stanek EJ, Hartmann K, Horny HP, Valent P and Reiter A. Efficacy and

Safety of Midostaurin in Advanced Systemic Mastocytosis. N Engl J Med.

2016;374:2530-2541. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1513098 PMid:27355533

- Valent

P, Akin C, Sperr WR, Escribano L, Arock M, Horny HP, Bennett JM and

Metcalfe DD. Aggressive systemic mastocytosis and related mast cell

disorders: current treatment options and proposed response criteria.

Leuk Res. 2003;27(7): 635-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2126(02)00168-6

- Cheson

BD, Bennett JM, Kantarjian H, Pinto A, Schiffer CA, Löwenberg B, Beran

M, de Witte TM, Stone RM, Mittelman M, Sanz GF, Wijermans PW, Gore S,

Greenberg PL, World Health Organization(WHO) international working

group. Report of an international working group to standardize response

criteria for myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2000;96(12):3671-74. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.V96.12.3671

- Cheson

BD, Greenberg PL, Bennett JM, Lowenberg B, Wijermans PW, Nimer SD,

Pinto A, Beran M, de Witte TM, Stone RM, Mittelman M, Sanz GF, Gore SD,

Schiffer CA and Kantarjian H. Clinical application and proposal for

modification of the International Working Group (IWG) response criteria

in myelodysplasia. Blood. 2006;108(2): 419-25.

https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2005-10-4149 https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2005-10-4149 PMid:16609072

- Gotlib

J, Pardanani A, Akin C, Reiter A, George T, Hermine O, Kluin-Nelemans

H, Hartmann K, Sperr WR, Brockow K, Schwartz LB, Orfao A, DeAngelo DJ,

Arock M, Sotlar K, Horny HP, Metcalfe DD, Escribano L, Verstovsek S,

Tefferi A and Valent P. International Working Group-Myeloproliferative

Neoplasms Research and Treatment (IWG-MRT) & European Competence

Network on Mastocytosis (ECNM) consensus response criteria in advanced

systemic mastocytosis. Blood. 2013;121:2393-2401. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2012-09-458521 PMid:23325841 PMCid:PMC3612852

- Tzogani

K, Yu Yang, Meulendijks D, Herberts C, Hennik P, Verheijen R, Wangen T,

Håkonsen GD, Kaasboll T, Dalhus M, Bolstad B, Salmonson T, Gisselbrecht

C and Pignatti F. European Medicines Agency review of midostaurin

(Rydapt) for the treatment of adult patients with acute myeloid

leukaemia and systemic mastocytosis. ESMO Open. 2019;4(6):e000606. https://doi.org/10.1136/esmoopen-2019-000606 PMid:32392175 PMCid:PMC7001097

- Midostaurin. Summary of Product Characteristic. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/rydapt-epar-product-information_en.pdf (Accessed 26 June, 2022)

- DeAngelo

DJ, George TI, Linder A, Langford C, Perkins C, Ma J, Westervelt P,

Merker JD, Berube C, Coutre S, Liedtke M, Medeiros B, Sternberg D,

Dutreix C, Ruffie PA, Corless C, Graubert TJ and Gotlib J. Efficacy and

safety of midostaurin in patients with advanced systemic mastocytosis:

10-year median follow-up of a phase II trial. Leukemia.

2018;32:470-478. https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2017.234 PMid:28744009

- Gotlib

J, Kluin-Nelemans HC, Akin C, Hartmann K, Valent P and Reiter A.

Practical management of adverse events in patients with advanced

systemic mastocytosis receiving midostaurin. Expert Opin Biol Ther.

2021:1-12. https://doi.org/10.1080/14712598.2021.1837109 PMid:33063554

- Jawhar

M, Schwaab J, Horny HP, Sotlar K, Naumann N, Fabarius A, Valent P,

Cross NCP, Hofmann WK, Metzgeroth G and Reiter A. Impact of centralized

evaluation of bone marrow histology in systemic mastocytosis. Eur J

Clin Invest. 2016;46:392-397. https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.12607 PMid:26914980

- Greiner

G, Gurbisz M, Ratzinger F, Witzeneder N, Simonitsch-Klupp I,

Mitterbauer- Hohendanner G, Mayerhofer M, Müllauer L, Sperr WR, Valent

P and Hoermann G. Digital PCR: A Sensitive and Precise Method for KIT

D816V Quantification in Mastocytosis. Clin Chem. 2018;64:547-555. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2017.277897 PMid:29237714 PMCid:PMC7115889

- Arock

M, Sotlar K, Akin C, Broesby-Olsen S, Hoermann G, Escribano L,

Kristensen TK, Kluin-Nelemans HC, Hermine O, Dubreuil P, Sperr WR,

Hartmann K, Gotlib J, Cross NCP, Haferlach T, Garcia-Montero A, Orfao

A, Schwaab J, Triggiani M, Horny HP, Metcalfe DD, Reiter A and Valent P

. KIT mutation analysis in mast cell neoplasms: recommendations of the

European Competence Network on Mastocytosis. Leukemia.

2015;29:1223-1232. https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2015.24 PMid:25650093 PMCid:PMC4522520

- Criscuolo M, Fianchi L, Maraglino AME and Pagano L. Mastocytosis: One Word for Different Diseases. Oncol Ther. 2018;6:129-140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40487-018-0086-2 PMid:32700030 PMCid:PMC7360005

- Valent

P, Akin C, Escribano L, Fodinger M, Hartmann K, Brockow K, Castells M,

Sperr WR, Kluin-Nelemans HC, Hamdy NAT, Lortholary O, Robyn J, van

Doormaal J, Sotlar K, Hauswirth AW, Arock M, Hermine O, Hellmann A,

Triggiani M, Niedoszytko M, Schwartz LB, Orfao A, Horny HP and Metcalfe

DD. Standards and standardization in mastocytosis: consensus statements

on diagnostics, treatment recommendations and response criteria. Eur J

Clin Invest. 2007;37:435-453. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2362.2007.01807.x PMid:17537151

- Valent

P, Akin C, Sperr WR, Horny HP, Arock M, Lechner K, Bennett JM and

Metcalfe DD. Diagnosis and treatment of systemic mastocytosis: state of

the art. Br J Haematol. 2003;122:695-717. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04575.x PMid:12930381

- Gotlib J, Reiter A. ECNM 2020 Annual Meeting, Vienna, Austria.

- Shomali

W and Gotlib J. Response Criteria in Advanced Systemic Mastocytosis:

Evolution in the Era of KIT Inhibitors. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:2983. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22062983 PMid:33804174 PMCid:PMC8001403

- Jawhar

M, Schwaab J, Naumann N, Horny HP, Sotlar K, Haferlach T, Metzgeroth G,

Fabarius A, Valent P, Hofmann WK, Cross NCP, Meggendorfer M and Reiter

A. Response and progression on midostaurin in advanced systemic

mastocytosis: KIT D816V and other molecular markers. Blood.

2017;130:137-145. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2017-01-764423 PMid:28424161

- Naumann

N, Jawhar M, Schwaab J, Kluger S, Lubke J, Metzgeroth G, Popp HD,

Khaled N, Horny HP, Sotlar K, Valent P, Haferlach C, Göhring G,

Schlegelberger B, Meggendorfer M, Hofmann WK, Cross NCP, Reiter A and

Fabarius A. Incidence and prognostic impact of cytogenetic aberrations

in patients with systemic mastocytosis. Genes Chromosomes Cancer.

2018;57:252-259. https://doi.org/10.1002/gcc.22526 PMid:29341334

- Knapper

S, Cullis J, Drummond MW Evely R, Everington T, Hoyle C, McLintock L,

Poynton C and Radia D. Midostaurin a Multi-Targeted Oral Kinase

Inhibitor in Systemic Mastocytosis: Report of An Open-Label

Compassionate Use Program in the United Kingdom. Blood.

2011:118(21):5145. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.V118.21.5145.5145

- Galinsky

I, Coleman M and Fechter L. Midostaurin: Nursing Perspectives on

Managing Treatment and Adverse Events in Patients With FLT3

Mutation-Positive Acute Myeloid Leukemia and Advanced Systemic

Mastocytosis. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2019;23:599-608. https://doi.org/10.1188/19.CJON.599-608 PMid:31730602

- Chandesris

MO, Damaj G, Lortholary O and Hermine O. Clinical potential of

midostaurin in advanced systemic mastocytosis. Blood Lymphat Cancer.

2017;7:25-35. https://doi.org/10.2147/BLCTT.S87186 PMid:31360083 PMCid:PMC6467340

- Hartmann

K, Gotlib J, Akin C, Hermine O, Awan FT, Hexner E, Mauro MJ, Menssen

HD, Redhu S, Knoll S, Sotlar K, George TI, Horny HP, Valent P, Reiter A

and Kluin- Nelemans HC. Midostaurin improves quality of life and

mediator-related symptoms in advanced systemic mastocytosis. J Allergy

Clin Immunol. 2020;146:356-366.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2020.03.044 PMid:32437738

- Reiter

A, Kluin-Nelemans HC, George T, Akin C, DeAngelo DJ, Awan F, Hexner E,

Mauro M, Schwaab J, Jawhar M, Sternberg D, Berkowitz N, Niolat J,

Huntsman Labed A, Hartmann K, Horny HP, Valent P and Gotlib J. Pooled

survival analysis of midostaurin clinical study data (D2201+A2213) in

patients with advanced systemic mastocytosis compared with historical

controls. Haematologica. 2017;102(s2):321.

- Zanelli

M, Pizzi M, Sanguedolce F et al. Gastrointestinal Manifestations in

Systemic Mastocytosis: The Need of a Multidisciplinary Approach.

Cancers. 2021;13(13):3316. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13133316 PMid:34282774 PMCid:PMC8269078

- Sokol

H, Georgin-Lavialle S, Canioni D et al. Gastrointestinal manifestations

in mastocytosis: A study of 83 patients. Journal of Allergy and

Clinical Immunology. 2013;132(4): 866-873.e3 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2013.05.026 PMid:23890756

- Lee

P, George TI, Shi H, et al. Systemic mastocytosis patient experience

from Mast Cell Connect, the first patient-reported registry for

mastocytosis. Blood. 2016;128(22). [abstract 4783]. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.V128.22.4783.4783

- Chandesris

MO, Damaj G, Canioni D, Brouzes C, Lhermitte L, Hanssens K, Frenzel L,

Cherquaoui Z, Durie I, Durupt S, Gyan E, Beyne-Rauzy O, Launay D, Faure

C, Hamidou M, Besnard S, Diouf M, Schiffmann A, Niault M, Jeandel PY,

Ranta D, Gressin R, Chantepie S, Barete S, Dubreuil P, Bourget P,

Lortholary O, Hermine O and CEREMAST Stydy Group. Midostaurin in

Advanced Systemic Mastocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2605-2607. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc1515403 PMid:27355555

- Cura

P, Salomon G, Bulai Livideanu C, Tournier E et al. Midostaurin-induced

lichenoid photoallergic reaction in a patient with systemic

mastocytosis. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/phpp.12778 PMid:35103335

- Valent

P, Akin C, Bonadonna P, Brockow K, Niedoszytko M, Nedoszytko B,

Butterfield JH, Alvarez-Twose I, Sotlar K, Schwaab J, Jawhar M, Reiter

A, Castells M, Sperr WR, Kluin-Nelemans HC, Hermine O, Gotlib J,

Zanotti R, Broesby-Olsen S, Horny HP, Triggiani M, Siebenhaar F, Orfao

A, Metcalfe DD, Arock M and Hartmann K. Risk and management of patients

with mastocytosis and MCAS in the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic:

Expert opinions. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146:300-306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2020.06.009 PMid:32561389 PMCid:PMC7297685

- SIE/GITMO. Available at: https://www.siematologia.it/suggerimenti-pratici-per-la-gestione-dei-pazienti-oncoematologici-nella-seconda-pandemia. (Accessed 11 Feb, 2020).

- Rama

TA, Moreira A and Castells M. mRNA COVID-19 vaccine is well tolerated

in patients with cutaneous and systemic mastocytosis with mast cell

activation symptoms and anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol.

2021;147:877-878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2021.01.004 PMid:33485650 PMCid:PMC7816615

- Lazarinis

N, Bossios A and Gülen T. COVID-19 vaccination in the setting of

mastocytosis-Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine is safe and well tolerated. J

Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;Feb 3:S2213-2198(22)00117-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2022.01.037 PMid:35123098 PMCid:PMC8810433

- Bonadonna

P, Brockow K, Niedoszytko M, Elberink HO, Akin C, Nedoszytko B,

Butterfiel JH, Alvarez-Twose I, Sotlar K, Schwaab J, Jawhar M, Castells

M, Sperr WR, Hermine O, Gotlib J, Zanotti R, Reiter A, Broesby-Olsen S,

Bindslev-Jensen C, Schwarts LB, Horny HP, Radia D, Triggiani M, Sabato

V, Carter MC, Siebenhaar F, Orfao A, Grattan C, Metcalfe DD, Arock M,

Gulen T, Hartmann K and Valent P. COVID-19 Vaccination in Mastocytosis:

Recommendations of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis

(ECNM) and American Initiative in Mast Cell Diseases (AIM). J Allergy

Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9:2139-2144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2021.03.041 PMid:33831618 PMCid:PMC8019658

[TOP]