Peritoneal

lymphomatosis (PL) is an unusual extranodal presentation of non-Hodgkin

lymphoma (NHL), with relatively few cases reported in the literature.[1] Unlike pleural effusion, which frequently occurs in any NHL, the involvement of the peritoneal cavity is uncommon.[2]

Peritoneal carcinomatosis, tuberculous peritonitis, and metastatic

tumors are the most common causes of peritoneal thickening with

effusion, but PL should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Peritoneal lymphomatosis is usually related to diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma and refers to the seeding of the parietal peritoneum and

surface of the covered abdominal organs by lymphoma cells. Abdominal

pain and distension are the most frequent clinical symptoms of PL.[1]

We report a case of a 55-years-old male with a prior diagnosis of

peripheral T-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified (PTCL-NOS), who

presented with ascites and suspected peritoneal lymphomatosis. Clinical

signs and imaging were suggestive of a relapse of PTCL-NOS.

In

August 2021, a 55-years-old male was admitted to our hospital because

of abdominal distension, nausea, and vomiting. He had a history of

prostatic cancer treated surgically in 2016 and PTCL-NOS treated in

2017 with six cycles of CHOEP (Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin,

Vincristine, Etoposide, and Prednisone) followed by autologous stem

cell transplant (ASCT) obtaining complete disease remission. On

admission, laboratory findings showed anemia (Hb 9.4 g/dL), mild

leucocytosis (WBC 12630/mm3 Neu 11540/mm3),

hypoalbuminemia (2.8 g/dL), high serum creatinine levels (4,9 mg/dL),

hyperuricemia (16,6 mg/dL), and elevated LDH levels (1297 UI/L, normal

value <225 UI/L). On clinical examination, he had ascites but no

palpable superficial lymph nodes. Computed tomography (CT) without

contrast showed peritoneal effusion and thickening at mesenteric and

mesogastric fatty tissue levels. Splenomegaly (16 cm) and the portal

vein of increased caliber (17 mm) were also detected. A paracentesis

was performed, obtaining 4 liters of a cloudy, straw-colored ascitic

fluid (AF) with high protein content (3.9 gr/dL), remarkable LDH values

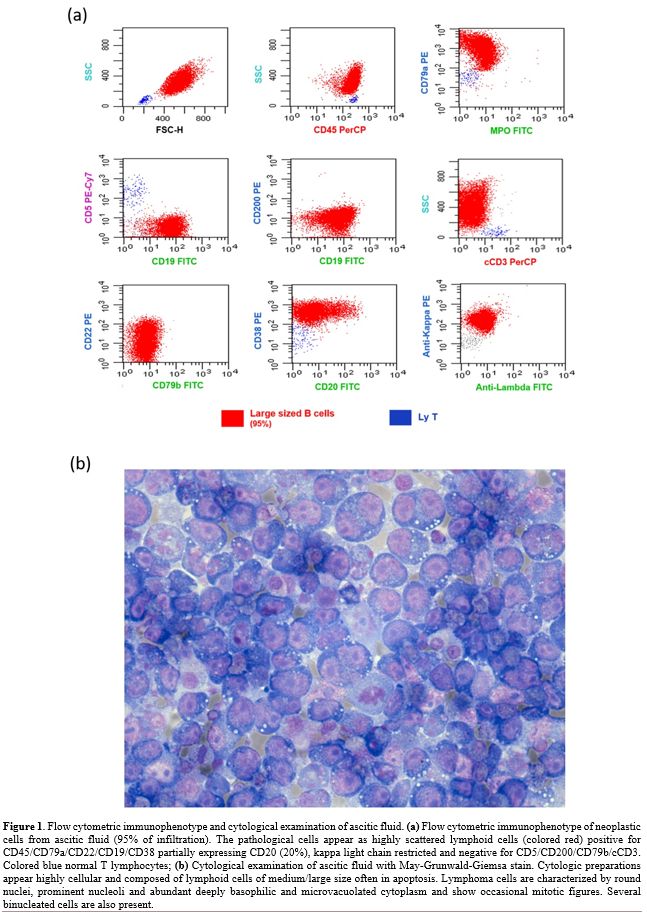

(4296 UI/L), and glucose (16 mg/dL). We studied the AF with eight-color

multiparametric flow cytometry (MFC) using combinations of monoclonal

antibodies. MFC analysis of the AF detected 95% of highly scattered

lymphoid B cells, positive for

CD45/CD79a/CD19/CD22/CD38/CD18/CD11a/CD27/CD49d/HLA-DR, CD20 partially

expressed (20%), kappa light chain restricted and negative for

CD5/CD200/FMC7/CD79b/CD10/VS38/CD13/CD33/CD14/CD15/CD11b/CD16/CD56/CD138/MPO/cCD3/NG2/CD123

(Figure 1a). Considering the

previous diagnosis of PTCL-NOS, an accurate assessment of T-cells was

also performed through immunophenotypic analysis of V Beta Repertoire,[3] which did not detect alterations in any of the 24 families studied.

Cytological

examination of ascitic fluid (1000 ml) with May-Grunwald-Giemsa (MGG)

stain revealed numerous lymphoid cells of medium to large size, often

in apoptosis and sometimes in mitosis. Most cells had round nuclei,

prominent nucleoli, and abundant deeply basophilic finely vacuolated

cytoplasm (Figure 1b). The

remaining concentrated sediment was fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in

paraffin, and processed to cell block to perform immunohistochemistry

(IHC). Lymphoma cells were immunoreactive for CD79a, CD20 (about 30%),

PAX5 (weak and diffuse), MUM1, cMyc (>40%) and BCL2 (>50%) and

non-immunoreactive for HHV8, CD3, CD5, CD4, CD8, CD10, CD30, CD138, and

BCL6. We performed a molecular biology investigation to evaluate T-cell

clonality arising out of a previous diagnosis of PTCL-NOS and to study

the B-cell population in the first biopsy at the presentation in 2017.

The lymph node and AF were investigated for the presence of

immunoglobulins (IG) and T-receptor (TR) clonal rearrangements by qualitative

polymerase chain reaction (PCR). All positive targets were sequenced to

identify the type of rearrangement and its clonal feature. The

screening showed different targets: one was immunoglobulin heavy chain

(IGH) gene rearrangements on ascitic fluid, and two resulted in TR

gamma chain positive on lymph node biopsy. No common targets were

identified between the two samples. Based on these findings, the

patient was diagnosed with large B-cell lymphoma of new onset,

presenting as peritoneal lymphomatosis. Gastrointestinal localization

of disease was excluded by esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGDS) and

recto-colon-sigmoidoscopy (RSCS). Due to the patient poor clinical

conditions, a Gemcitabine-based regimen was chosen to obtain a mild

clinical improvement. After one week, he received a second infusion of

Gemcitabine, but three days later, his clinical conditions worsened

again due to fever and pancytopenia. Considering the normalization of

serum creatinine (1.1 mg/dL) and the recurrence of abdominal

distention, a total body CT scan with contrast confirmed the presence

of an abundant amount of ascitic effusion and mesenteric thickening as

an omental cake pattern, referring to peritoneal localization of the

disease. Small mesenteric lymphadenopathies (15 mm) were observed.

Unfortunately, clinical conditions worsened, and the patient died the

following day.

Peritoneal

lymphomatosis is a rare form of extranodal lymphoproliferative disease,

frequently associated with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and

Burkitt's lymphoma.[3] Considering the recent history

of PTCL-NOS in our patient, a relapse of the T-cell disease was

suspected, although T-cell peritoneal lymphomatosis is extremely rare

and usually secondary to intestinal localization.[4]

Thanks to a prompt MFC exam with cytology and IHC afterward, we

obtained an early diagnosis by avoiding a biopsy exam. Although DLBCL

is ideally diagnosed from an excisional biopsy of a suspicious lymph

node or tissue, morphologic and cytometry exams should be considered

when an invasive diagnostic procedure is not possible.

Immunophenotyping by MFC is a rapid and efficient technique adjunct to

conventional diagnostic cytopathology in evaluating serous effusions

for lymphomatous involvement.[5-6] Studies like MFC

and IHC staining help lead to an accurate diagnosis allowing the

identification of the molecular characteristics of the lymphoma and its

immunophenotype, which dictate treatment decisions.[7-10]

This case was interesting as the clinical signs and symptoms could

suggest a relapse of PTCL-NOS diagnosed and treated four years before;

however, FCM, cytology with IHC, and molecular biology investigations

excluded this hypothesis.

In conclusion, MFC could be an extremely

useful and rapid method in the integrated diagnostic process with

cytology and IHC to obtain a proper diagnosis of NHL to quickly start

appropriate therapy, also in the absence of tumor samples for a

complete histopathology examination.