Mario Schiavoni1, Carlo Pruneti2, Sara Guidotti2, Alessandra Moscatello3, Francesca Giordano4, Antonella Coluccia5, Rita Carlotta Santoro6, Maria Francesca Mansueto7, Ezio Zanon8, Renato Marino9, Isabella Cantori10 and Raimondo De Cristofaro11.

1 Past

Director of Hemophilia and Rare Coagulopathies Center - Dept. of

Internal Medicine, "I. Veris Delli Ponti" Hospital-Scorrano-ASL Lecce,

Italy.

2 Clinical Psychology, Clinical

Psychophysiology, and Clinical Neuropsychology Labs., Dept. of Medicine

and Surgery, University of Parma, Italy.

3 Penitentiary Medicine - Socio-sanitary District ASL-Lecce, Italy.

4 Service of Pathological Addictions-Gallipoli-ASL Lecce, Italy.

5

Hemophilia and Rare Coagulopathies Center -Dept. of Internal Medicine,

" I. Veris Delli Ponti" Hospital-Scorrano-ASL Lecce, Italy.

6 Hemostasis and Thrombosis Unit, Pugliese-Ciaccio Hospital, Catanzaro, Italy.

7

Regional Reference Center for Coagulopathies in Children and Adults,

Hematology Unit, Oncology Dept.- Policlinico University, Palermo, Italy.

8

Multidisciplinary HUB Regional Center for Prevention, Prophylaxis, and

Advanced Treatment of Hemophilic Arthropathy, General Medicine

University Hospital of Padua, Italy.

9 Hemophilia and Thrombosis Center, Policlinico-University, Bari, Italy.

10 Haemophilia Center, Department of Transfusion Medicine, Hospital of Macerata, Macerata, Italy.

11 Hemorrhagic and Thrombotic Diseases Center, Foundation "A. Gemelli" IRCCS University Hospital, Rome, Italy.

Correspondence to: Mario

Schiavoni. Past Director of Hemophilia and Rare Coagulopathies Center

- Dept. of Internal Medicine, "I. Veris Delli Ponti"

Hospital-Scorrano-ASL Lecce, Italy. E-mail:

marioschiavoni@gmail.com

Published: January 1, 2023

Received: September 22, 2022

Accepted: December 19, 2022

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2023, 15(1): e2023005 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2023.005

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Background:

The health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of people with hemophilia

(PWH) is an important issue, especially considering people suffering

from chronic diseases beyond hemophilia. The principal aim of this

study was to investigate the presence and relevance of psychological

symptoms, both internalizing and externalizing, lifestyle, and HRQoL in

a group of Italian PWH with chronic bloodborne co-infections and

comorbidities. Furthermore, the research describes the association

between psychological aspects and the impact of disease-related

characteristics (type of hemophilia, presence of co-infections, and

comorbidities) on them.

Methods:

Seventy patients (mean age 46.77±11.3), 64 with severe hemophilia A

(Factor VIII: C < 1 IU/dL) and 6 with severe hemophilia B (Factor IX

<1 IU/dL), were consecutively recruited from seven Hemophilia

Centers in Italy of Italian Association of Hemophilia Centers (AICE).

In order to assess psychological symptoms, HRQoL, and lifestyle, three

psychological questionnaires were administered (the SCL-90-R, SF-36,

and PSQ, respectively).

Results:

A general decline in the quality of life and an increase in the

tendency to adopt a lifestyle characterized by hyperactivity emerged.

Inverse correlations were found between HRQoL and psychological

distress. Although the SCL-90-R did not reveal symptoms above the

clinical cut-off, co-infections significantly increased anxiety,

depression, somatizations, paranoia, and social withdrawal. Lastly,

HRQoL is impaired by co-infections as well as comorbidities.

Conclusion: Our preliminary results must be confirmed to deepen the findings between mental health and hemophilia.

|

Introduction

Hemophilia

is an inherited hemorrhagic disorder that, in the most severe forms,

causes deep physical and psychological discomfort, mainly due to often

life-threatening bleeding. In the last 20 years, great progress in the

multidisciplinary management of PWH has been achieved. The availability

of increasingly innovative replacement and non-substitutive treatments

given on prophylaxis has radically changed the expectancy and the

HRQoL, particularly in the younger generations with severe hemophilia A

and B.[1]

Several previous studies investigated

the presence of psychological symptoms and the HRQoL in PWH. Most

research agrees with the idea that specific factors in the medical

history can determine a decline in specific components of HRQoL, such

as physical activity, physical health, and social and interpersonal

functioning.[2-5] Other studies underlined the role of factors such as work status and perceived physical pain.[6,7]

Nevertheless, many problems are still associated with older adults

affected by age-related comorbidities (diabetes, cardiovascular and

respiratory diseases, renal insufficiency, cancer, etc.) that require

specialized medical and psychological interventions. It is well known

that the most serious comorbidities are chronic liver diseases closely

related to hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV) infections, as well

as the sequelae caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)[8,9]

occurred in the 70-80s by the use of not virus-inactivated

plasma-derived concentrates. However, even though vaccination against

hepatitis B definitively defeated the virus in new generations,

specific therapies against hepatitis C were applied,[10] and combined therapy with highly active anti-retroviral drugs slowed the progression of HIV,[11]

these infections keep on influence the concept of the disease and still

have an impact on the mental health of people affected.[12]

The

psychological dynamics in HIV-positive PWH were analyzed over the years

by considering various parameters. Increased stress and anxiety in a

population of HIV-positive hemophiliacs were observed. In addition,

psychosocial problems related to the level of school education,

familiarity with psychiatric illnesses, or a couple of problems were

also described. More specifically, HIV-positives showed a greater

negative impact on their sexual behaviors with a significantly higher

prevalence of sexual dysfunctions than HIV-negatives.[13]

However, completely different results were found by Italian authors

that demonstrated that HIV-negative hemophiliacs have worse anxiety and

depression scores, reporting more confusion and fear, than

HIV-positives.[14]

At the same time, many

research projects help to understand how to address these issues and

manage physical and psychological symptoms associated with HIV

infection.[15] Similarly, changes in psychological dynamics are also observed in hemophiliacs with age-related comorbidities.[16]

The

current literature still highlights the need to investigate these

aspects further and broaden the clinical interest in psychological

symptoms not yet evaluated. For instance, relevant emotional reactions

towards the disease were neglected, such as the presence of

externalizing symptoms (anger/hostility, paranoid ideation, etc.)

typical in the literature discussing other severe chronic diseases

(obstructive pulmonary disease, multiple sclerosis, alexithymia).[17-20]

Aims of the study.

The main purpose of our research was to describe specific psychological

aspects: psychopathological symptoms, both internalizing (anxiety,

somatic complaints, obsessions and compulsions, depression) and

externalizing (hostility, paranoia, psychoticism, etc.), lifestyle, and

HRQoL in a hemophiliac sample. A further objective was to highlight the

possible association between the psychological aspects mentioned above.

Lastly, the impact of specific factors related to hemophilia (type A or

B, co-infections, and comorbidities) on the psychological dimensions

was investigated.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Study design.

In this multicenter observational study, 70 PWH (64 with severe

hemophilia A: Factor VIII: C < 1 IU/dL and 6 with severe hemophilia

B: Factor IX <1 IU/dL) were consecutively recruited from seven

Italian Hemophilia Centers (Bari, Catanzaro, Macerata, Padova, Roma,

Palermo, and Scorrano) belonging to AICE. Criteria for inclusion in the

study were age > 18 years old; medical diagnosis of hemophilia;

absence of sensory disturbances of sight and/or hearing that limit the

administration of the tests (i.e., previous head trauma, neurological

condition, alcoholism, or substance abuse, or neoplasms).

Ethical considerations.

Informed consent was required from all persons, as well as the approval

of the Ethics Committees of the respective Hemophilia Centers. This

study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and Italian privacy law

(Legislative decree No. 196/2003). No treatments or false feedback were

given, and no potentially harmful evaluation methods were used.

Participation was voluntary, and participants could drop out at any

time without any negative consequences. All data were stored only by

using an anonymous ID for each participant. Subjects' anonymity was

preserved, and the data obtained were used solely for scientific

purposes.

Measures.

After an accurate clinical interview, PWH underwent a

psychopathological assessment procedure by administering three

psychometric tests.

The Symptom Checklist-90-Revised was used to

investigate internalizing and externalizing symptoms such as

Somatization (SOM), Obsessive-compulsive (O-C), Interpersonal

Hypersensitivity (I-S), Depression (DEP), Anxiety (ANX), Hostility

(HOS), Phobic Anxiety (PHOB), Paranoid Ideation (PAR), and Psychoticism

(PSY) (cut-off=1.00).[21] The SCL-90-R provides three

global indices: the Global Severity Index (GSI) represents the

intensity of the level/depth of the distress; the Positive Symptom

Total (PST) corresponds to the total number of symptoms, and the

Positive Symptom Distress Index (PSDI) is used as an index of the

subject's response style to the suffering.[22,23]

The

Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) was administered to evaluate the

HRQoL. It is composed of eight scales: Physical Functioning (PF), Role

(limitations) Physical (RP), General Health (GH), Bodily Pain (BP),

Vitality (VT), Role (limitations), Emotional (RE), Mental Health (MH),

and Social Functioning (SF). Questions and sub-scales of the SF-36 are

organized so that a higher score represents better health of the

subject.[24]

The P Stress Questionnaire (PSQ)

was performed to detect whether there is a present risk for

stress-related physical disorders attributable to some characteristics

of the personality configuration known as "Type A behavior".[25]

The PSQ tool made up of 32 items, grouped into six scales: Sense of

Responsibility (SR), Vigor (V), Stress Disorders (SD), Precision and

Punctuality (PP), Spare Time (ST), and Hyperactivity (H). The

standardization provides conversion into Stanine scores that are proper

for scores that do not fall below 10 standard deviations. The Stanine

(STAndard NINE) is a method of scaling test scores that have a

distribution between 1 and 9 with mean=5 and standard deviation=1.96.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel and IBM SPSS

Statistics software (Version 28.0.1.0). Considering the small sample

size and the presence of unbalanced groups when divided by type of

hemophilia, co-infections, and comorbidities, non-parametric

statistical analyses were computed. First, descriptive analyses on the

total sample were conducted: average values (mean and standard

deviation) of the scores obtained from the total sample in the

SCL-90-R, SF-36, and PSQ scales were calculated. In order to highlight

possible associations between the psychological dimensions assessed, a

Spearman Correlation was then performed considering the sub-scales of

the SCL-90-R and the total scores of the SF-36 and the PSQ. In order to

investigate the impact of specific factors related to hemophilia (type

of disease, presence of co-infections, and comorbidities) on the

psychological aspects assessed, the following analyses were made: a

Mann-Whitney U tests for independent samples were used to calculate

possible significant differences between type A group vs. Type B group

considering symptoms (SCL-90-R), lifestyle (PSQ), and HRQoL (SF-36); a

Mann-Whitney U tests for independent samples were made to detect

possible significant differences between a co-infections group compared

with a group without co-infections considering symptoms (SCL-90-R),

lifestyle (PSQ), and HRQoL (SF-36); finally a Mann-Whitney U tests for

independent samples was performed in order to assess possible

significant differences between groups with comorbidities compared with

a group without comorbidities taking into account symptoms (SCL-90-R),

lifestyle (PSQ), and HRQoL (SF-36).

Results

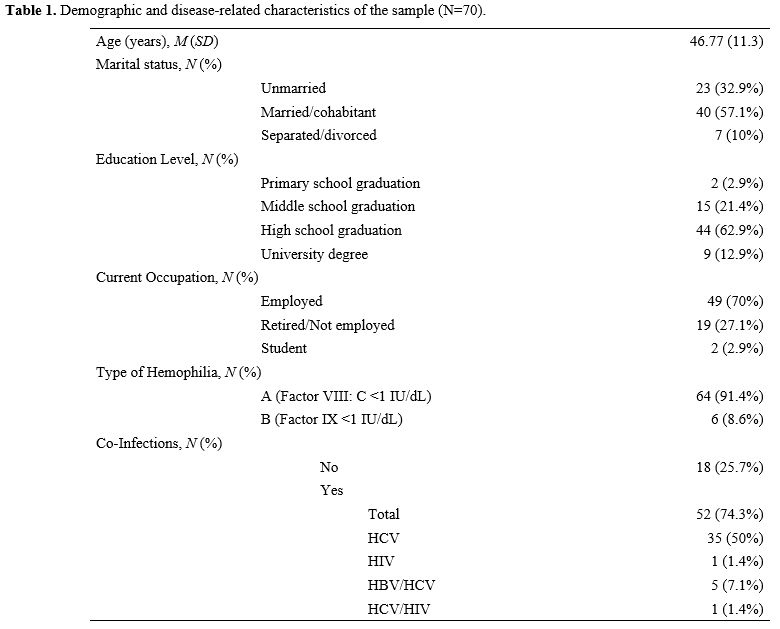

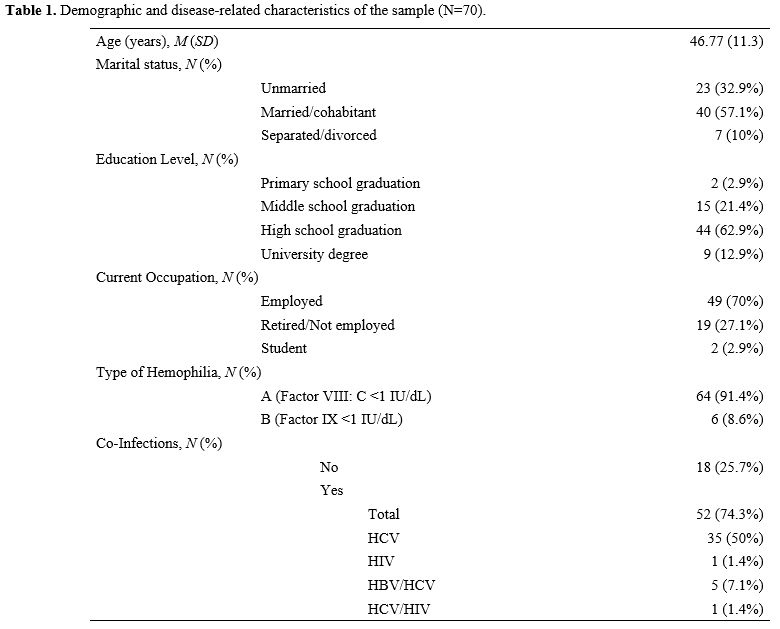

Description of the Sample. Demographic and disease-related characteristics of the total sample are shown in Table 1.

|

- Table 1. Demographic and disease-related characteristics of the sample (N=70).

|

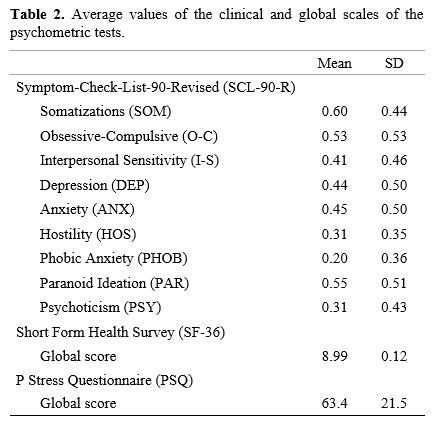

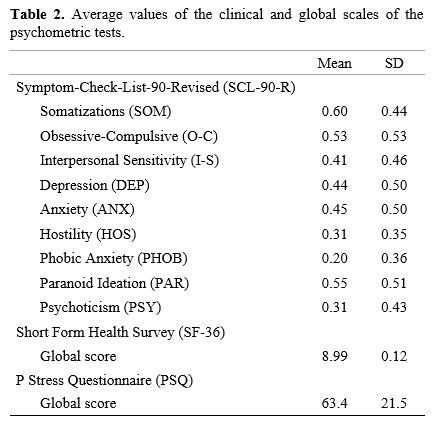

Descriptive analysis of the total sample.

Firstly, the SCL-90-R did not show scores indicative of

psychopathological symptoms of relevance (above the clinical cut-off of

1.00) while, considering the global score of the SF-36, a tendency to

perceive an impoverishment in one's health in the last year emerged.

Lastly, the descriptive analysis conducted on the total score of the

PSQ highlights the tendency to adopt behaviors and lifestyles

characterized by a high sense of responsibility, vigor, precision and

punctuality, hyperactivity, and somatic complaints (Table 2).

|

- Table 2. Average values of the clinical and global scales of the psychometric tests.

|

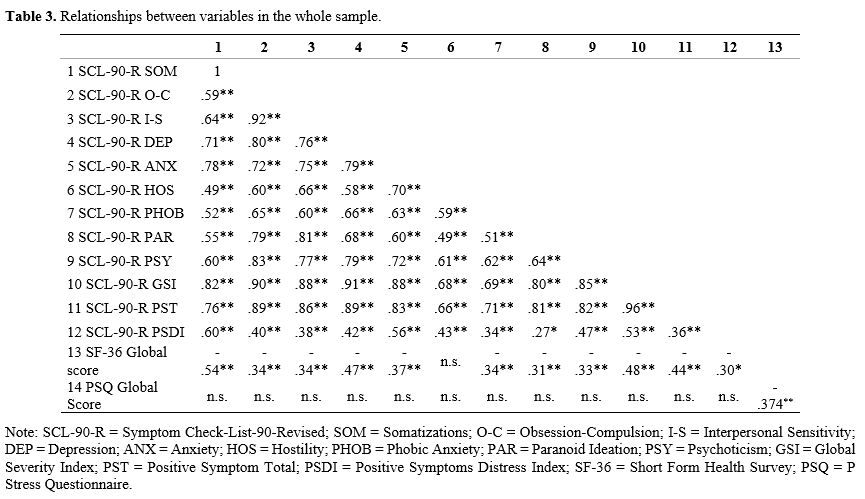

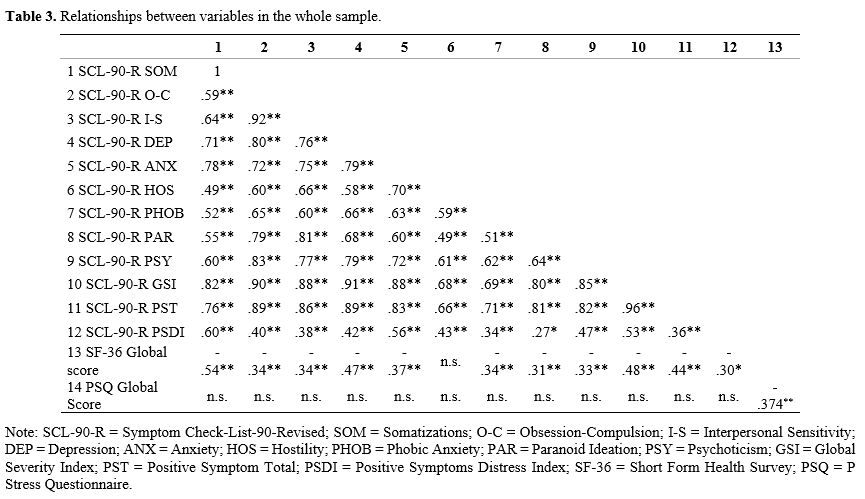

About

the three measures, the possible linear relation between them was

investigated through Spearman's Rho coefficient. In addition to the

significant associations that emerged between all the clinical and

global scales of the SCL-90-R, significant correlations can be observed

between the global score of the SF-36 and those of the SCL-90-R. More

specifically, it appears that psychological symptoms increase as the

quality-of-life decreases. However, an opposite trend can be

hypothesized: as the state of physical and mental health decreases,

symptoms related to anxiety, phobic anxiety, depression, obsession and

compulsion, somatic complaints, interpersonal hypersensitivity,

paranoid ideation, and psychoticism increase. Furthermore, the global

score of the SF-36 shows a moderate inverse correlation with the global

score of the PSQ (Table 3).

|

- Table 3. Relationships between variables in the whole sample.

|

Comparison between sub-groups.

In order to identify any significant differences in the manifestation

of psychological distress attributable to disease-related

characteristics (type A or B, presence or not of co-infections and

comorbidities), the differences between these groups were assessed. The

comparison of the scores of the SCL-90-R, SF-36, and PSQ according to

the type of hemophilia (A or B) did not show noteworthy aspects. For

none of these scales, there were no significant differences. On the

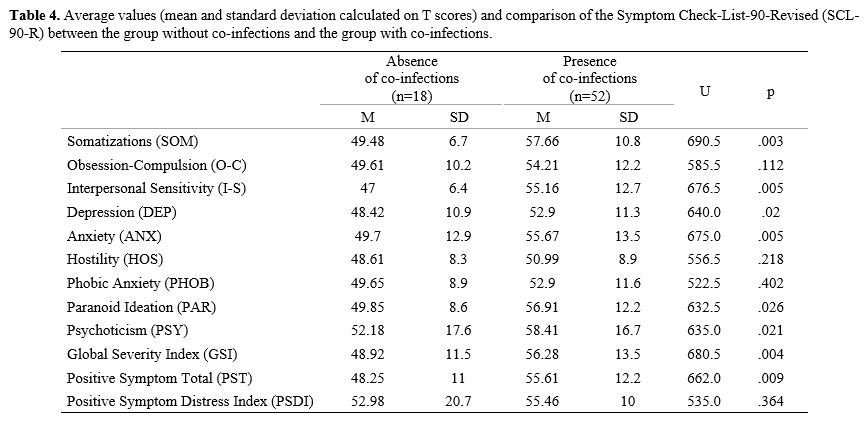

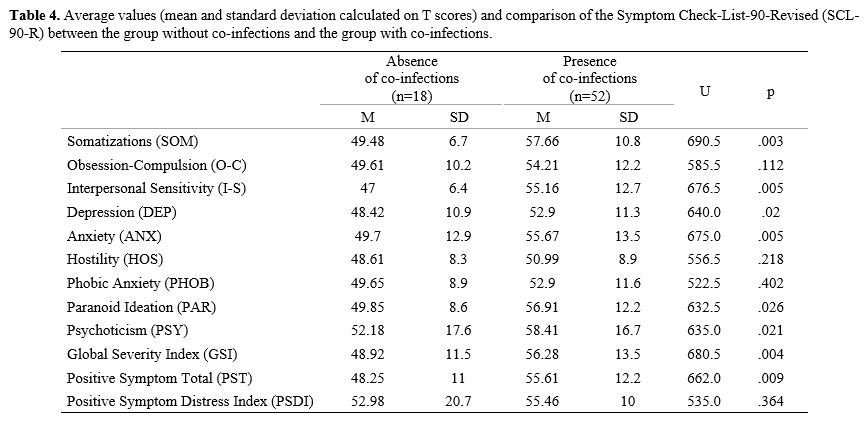

contrary, the Mann-Whitney's U test that compared the scores of the

psychological measures considering the presence of co-infections vs.

the absence of co-infections highlighted noteworthy aspects. More

specifically, significant differences between groups emerge both for

SCL-90-R and for SF-36. It seems that co-infections presence favors an

increase in psychological symptoms, internalizing, such as somatic

complaints, interpersonal hypersensitivity, depression, anxiety, and

externalizing, such as paranoid ideation and psychoticism. The scores

of two global indices, the GSI and PST, are also significantly higher

in the group with co-infections (Table 4).

|

- Table 4. Average

values (mean and standard deviation calculated on T scores) and

comparison of the Symptom Check-List-90-Revised (SCL-90-R) between the

group without co-infections and the group with co-infections.

|

Furthermore,

the co-infections presence determines a statistically significant

worsening of the quality of life (U=270.5; p=.008).

The Mann

Whitney's U test was also performed to investigate possible differences

in the scores of SCL-90-R, SF-36, and PSQ between a group of PWH with

comorbidities and a group of PWH without comorbidities. No significant

differences emerge between these two groups, neither in the symptoms

assessed with the SCL-90-R scale nor in the behavioral and lifestyle

aspects investigated through the PSQ. Conversely, the presence of other

medical diseases in the anamnesis favors a reduction in the level of

HRQoL (U=251.0; p=.01).

Discussion

On

a descriptive level, the most interesting result is the significantly

high average score on the PSQ. These data indicate the frequent

tendency to adopt a lifestyle at risk of stress-related physical

disorders and behavior characterized by a high sense of responsibility,

vigor, hyperactivity, precision and punctuality, and reduced ability to

take free time from working activities. In this sample, one could

assume that there is a tendency to adopt a lifestyle that does not

favor the achievement of psychophysical balance but instead the

tendency to implement potentially risky health behaviors. Clinical

hypotheses are connected to the possible presence of an underestimation

of risk in terms of denial of illness and non-acceptance of the role of

the patient. For this reason, in a future perspective of evaluation, it

would be interesting to investigate the subjective perception of

disease connected to the adaptation to it (i.e., by Illness Behavior

Questionnaire).[26] Consistent with what has already

been widely described in the literature, the diagnosis of hemophilia is

envisaged as an obstacle in the life of these people who perceive a

limitation of their activities in favor of the protection of their

body.[5,6,27-29] For instance, some

authors argue that participation in activities, such as sports or

crowded social events, is influenced by the fear of incurring injuries

and bleeding.[30] Moreover, it has highlighted the

role of behavioral precautions, the uncertainty of actions, and the

fear of unexpected bleeding on depression, frustration, isolation, and

embarrassment.[31] Other studies confirmed some

aspects related to comorbidities (arthropathy, HCV/HBV/HIV

co-infections, liver cirrhosis due to HBV/HCV infections, and

coexisting heart and kidney diseases, for example) are ongoing

challenges that block the accepting health status in these persons.[32,33]

As experienced in our sample, the correlation between the perceived

quality of life and the adopted lifestyle further corroborates this

point. It is possible to sustain that a lifestyle characterized by high

activity levels is associated with a decrease in the state of health

perceived by the subject. Hence, the need to pay attention to the

lifestyle of these persons, stress management, positive thinking, and

eating habits emerges.[34]

Focusing on the

psychopathological symptoms, our group recorded no scores above the

clinical cut-off. However, noteworthy aspects emerged by investigating

the correlation between the scores of the other psychometric tests

administered. Confirming what already emerged in previous studies, the

state of health appears to have an inverse correlation with two global

indices of the SCL-90-R.[4,5,28-30]

This information describes the tendency to suffer psychologically more,

as the decline in quality of life, in terms of limitations deriving

from the physical disease, increases. Furthermore, confirming previous

studies, the HRQoL appears to have an inverse correlation with most

psychological symptoms, such as anxiety, phobic anxiety, depression,

obsessions and compulsions, interpersonal hypersensitivity, and somatic

complaints.[3-5,28-30,35]

Moreover, even the scores of paranoid ideation and psychoticism appear

to have an inverse relationship with the HRQoL, highlighting the

additional load of hostility, suspiciousness, withdrawal, and social

isolation on the state of health. However, due to our study's small

sample size, it is impossible to define the causal role of the symptoms

on the deterioration of the HRQoL. The opposite could also be true: a

reduction in psychophysical well-being could lead to mental suffering.

One

of the aims of this research was to investigate some disease-related

characteristics' effects on the observed psychological aspects.

Interesting data were highlighted by comparing the psychological

distress between the group of patients with co-infections with those of

the group without co-infections. Co-infections appear to have an

important role in increasing psychological distress in terms of

internalizing (anxiety, depression, somatic complaints) and

externalizing (paranoia and psychoticism) symptoms. If the last aspect

is considered, the expression of mental suffering on an interpersonal

level has been described for the first time. To our knowledge,

inadequacy, a sense of inferiority, self-depreciation, and

suspiciousness resulting in social withdrawal and isolation were never

detected. Our results effectively deepen previous studies supporting

the data that infections compromise the patient's well-being causing

medical complications and social impairment. Jones and colleagues focus

on HIV infection and argue that there is a possible risk factor for the

appearance of psychological symptoms, even before noticeable physical

signs.[36-40] The psychological dynamics in

HIV-positive PWH were analyzed over the years by considering only

parameters such as stress and the relationship between infections.

Specifically considering HIV and mental suffering, the association is

still confused even now that vaccinations and anti-retroviral therapies

slow the progression of the disease.[12]

Also,

considering the HRQoL, our findings agree with previous studies that

focused on co-infections impact on this aspect. For instance,

Cuesta-Barriuso et al. found significant differences between a group of

PWH with HIV/HCV and the group without co-infections in HRQoL

perceptions, concluding that the emotional representation of the

disease plays an influential role.[28] Consistent

with this assumption, other authors explained this association with the

assumption that the HRQoL would be influenced by the level of

acceptance of the infection and the ability to adapt to illness.[38,41,42,43]

Our

study underlines another aspect referred to as the HRQoL. It has been

observed that comorbidities affect the global perception of health but

not mental health. The various diseases the person suffers from

determine the perception of one's functional limitations.

In

summary, some important considerations emerge and suggest the need for

further studies. For instance, future research could investigate the

close relationship between the lifestyle characterized by hyperactivity

and the deterioration in terms of quality of life and the association

between the perception of limitations to the activities of daily living

and the increase in psychological distress. Furthermore, it would be

useful to constitute a sample in which the group of co-infected and

that of non-co-infected are balanced. This aspect would confirm the

higher levels of externalizing symptoms, including paranoia, in the

first group. In addition, various sub-groups of co-infected PWH could

highlight interesting differences.

Finally, we emphasize the need

always to consider the HRQoL, which in our study appears to be

compromised by comorbidities. Considering that quality of life is one

of the best indices for the clinician to estimate the patient's level

of well-being, it is important to investigate the psychological aspects

and the medical variables that can impact it.

Conclusions

The

results of our preliminary research focus on the well-being of PWH and

their emotional experience. Our results agree with literature reports

and confirm that co-infections influence the manifestation of distress

(in terms of anxiety and depression, while PWH experiences

comorbidities are a consistent limitation of their lives. In addition,

the study underlines for the first time that these patients also

experience externalizing symptoms, including interpersonal sensitivity,

embarrassment, and paranoia. Nevertheless, it has also emerged that the

psychological variables investigated are associated. More specifically,

a general decline in well-being is associated with more intense mental

distress, even at a sub-clinical level. First, our results must be

confirmed to deepen the findings between mental health and hemophilia.

The

poor clarity in the factors that favor the impairment in the perceived

HRQoL and mental health remains an important clinical issue, and future

studies must be carried out.

Unfortunately, more in-depth

statistical analyses could not be performed because of the small sample

size and its large heterogeneity. Nevertheless, further research may

investigate a cause-effect relationship between the adopted lifestyle

and the decrease in perceived HRQoL. In addition, it could be useful to

verify if a greater perception of the limitations of the disease

corresponds to effective psychological suffering and investigate how

personality and psychological symptoms interact with each other and

affect psychophysical well-being.

This preliminary research

underlines the importance of multidisciplinary and multidimensional

management where a psychological investigation supplements the

clinical-medical evaluation. Psychological stress is frequently

mentioned among the predisposing,[44] precipitating, or perpetuating factors[45]

of physical pathologies in most medical fields, including

cardiovascular events, malignancies, and neurodegenerative disorders.[46-48]

Despite these reports, the medicine units that benefit from the

presence of clinical psychologists with specific curricula are still

few. Nevertheless, psychological support is useful for understanding

the clinical picture better and providing tailored interdisciplinary

treatment.

References

- Davari M, Gharibnaseri Z, Ravanbod R, Sadeghi A.

Health status and quality of life in patients with severe hemophilia A:

A cross-sectional survey. Hematol Rep. 2019; 11(2):7894. doi:

10.4081/hr.2019.7894. https://doi.org/10.4081/hr.2019.7894 PMid:31285808 PMCid:PMC6589534

- Bago

M, Butkovic A, Preloznik Zupan I, Faganel Kotnik B, Prga I, Bacic Vrca

V, Zupancic Salek S. Association between reported medication adherence

and health-related quality of life in adult patients with haemophilia.

Int J Clin Pharm. 2021; 43(6):1500-1507. doi:

10.1007/s11096-021-01270-x. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-021-01270-x PMid:33928481

- Mohan

R, Radhakrishnan N, Varadarajan M, Anand S. Assessing the current

knowledge, attitude and behaviour of adolescents and young adults

living with haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2021; 27(2):e180-e186. doi:

10.1111/hae.14229. https://doi.org/10.1111/hae.14229 PMid:33278862

- Buckner

TW, Sidonio R Jr, Witkop M, Guelcher C, Cutter S, Iyer NN, Cooper DL.

Correlations between patient-reported outcomes and self-reported

characteristics in adults with hemophilia B and caregivers of children

with hemophilia B: analysis of the B-HERO-S study. Patient Relat

Outcome Meas. 2019; 10:299-314. doi: 10.2147/PROM.S219166. https://doi.org/10.2147/PROM.S219166 PMid:31572035 PMCid:PMC6755243

- Holstein

K, von Mackensen S, Bokemeyer C, Langer F. The impact of social factors

on outcomes in patients with bleeding disorders. Haemophilia. 2016;

22(1):46-53. doi: 10.1111/hae.12760. https://doi.org/10.1111/hae.12760 PMid:26207763

- Cutter

S, Molter D, Dunn S, Hunter S, Peltier S, Haugstad K, Frick N, Holot N,

Cooper DL. Impact of mild to severe hemophilia on education and work by

US men, women, and caregivers of children with hemophilia B: The

Bridging Hemophilia B Experiences, Results and Opportunities into

Solutions (B-HERO-S) study. Eur J Haematol. 2017; 98 Suppl 86:18-24.

doi: 10.1111/ejh.12851. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejh.12851 PMid:28319337

- FRMY

Cassis, A Buzzi, A Forsyth, M Gregory, D Nugent, C Garrido, T Pilgaard,

DL Cooper, A Iorio. Haemophilia Experiences, Results and Opportunities

(HERO) Study: influence of haemophilia on interpersonal relationships

as reported by adults with haemophilia and parents of children with

haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2014; 20(4):e287-95. https://doi.org/10.1111/hae.12454 PMid:24800872

- Isfordink

CJ, van Erpecum KJ, van der Valk M, Mauser-Bunschoten EP, Makris M.

Viral hepatitis in haemophilia: historical perspective and current

management. Br J Haematol. 2021; 195(2):174-185. doi:

10.1111/bjh.17438. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.17438 PMid:33955555

- Lowe GD. Haemophilia, blood products and HIV infection. Scott Med J. 1987; 32(4):109-11. doi: 10.1177/003693308703200404. https://doi.org/10.1177/003693308703200404 PMid:3672104

- Barry

V, Lynch ME, Tran DQ, Antun A, Cohen HG, DeBalsi A, Hicks D, Mattis S,

Ribeiro MJ, Stein SF, Truss CL, Tyson K, Kempton CL. Distress in

patients with bleeding disorders: a single institutional

cross-sectional study. Haemophilia. 2015; 21(6):e456-64.

doi:10.1111/hae.12748. https://doi.org/10.1111/hae.12748 PMid:26179213

- Bussin

R, Johnson SB. Psychosocial issues in hemophilia before and after the

HIV crisis: a review of current research. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1992;

14(6):387-403.doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(92)90006-v. https://doi.org/10.1016/0163-8343(92)90006-V PMid:1473709

- Dew

MA, Ragni MV, Nimorwicz P. Infection with human immunodeficiency virus

and vulnerability to psychiatric distress. A study of men with

hemophilia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990; 47(8):737-44. doi:

10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810200045006. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810200045006 PMid:2378544

- Catalan

J, Klimes I, Bond A, Day A, Garrod A, Rizza C. The psychosocial impact

of HIV infection in men with haemophilia: controlled investigation and

factors associated with psychiatric morbidity. J Psychosom Res. 1992;

36(5):409-16. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(92)90001-i. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3999(92)90001-I PMid:1619581

- Marsettin

EP, Ciavarella N, Lobaccaro C, Ghirardini A, Bellocco R, Schinaia N.

Psychological status of men with haemophilia and HIV infection:

two-year follow-up. Haemophilia. 1995; 1(4):255-61. doi:

10.1111/j.1365-2516.1995.tb00085.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2516.1995.tb00085.x PMid:27214633

- Gil

F, Arranz P, Lianes P, Breitbart W. Physical symptoms and psychological

distress among patients with HIV infection. AIDS Patient Care. 1995;

9(1):28-31. doi: 10.1089/apc.1995.9.28. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.1995.9.28 PMid:11361352

- Coppola

A, Santoro C, Franchini M, Mannucci C, Mogavero S, Molinari AC, Schinco

P, Tagliaferri A, Santoro RC. Emerging issues on comprehensive

hemophilia care: preventing, identifying, and monitoring age-related

comorbidities. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2013; 39(7):794-802. doi:

10.1055/s-0033-1354424. Epub 2013 Sep 8.PMID: 24014070. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1354424 PMid:24014070

- Tzitzikos

G, Kotrotsiou E, Bonotis K, Gourgoulianis K. Assessing hostility in

patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Psychol

Health Med. 2019; 24 (5): 605-619. doi:10.1080/13548506.2018.1554253. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2018.1554253 PMid:30522331

- Oz

HS, Oz F. A psychoeducation program for stress management and

psychosocial problems in multiple sclerosis. Niger J Clin Pract. 2020;

23(11):1598-1606. doi:10.4103/njcp.njcp_462_19 https://doi.org/10.4103/njcp.njcp_462_19 PMid:33221788

- Grassi

L, Belvederi Murri M, Riba M, et al. Hostility in cancer patients as an

underexplored facet of distress. Psychooncology. 2021; 30(4):493-503.

doi:10.1002/pon.5594 https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5594 PMid:33205480

- Apgáua

LT, Jaeger A. Memory for emotional information and alexithymia A

systematic review. Dement Neuropsychol. 2019; 13(1):22-30. doi:

10.1590/1980-57642018dn13-010003. https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-57642018dn13-010003 PMid:31073377 PMCid:PMC6497026

- Derogatis LR. SCL-90-R: Administration, Scoring and Procedures Manual. Minneapolis, MN. National Computer Systems, 1994.

- Sarno

I, Preti E, Prunas A, Madeddu F. SCL-90-R Symptom Checklist-90-R

Adattamento italiano. Firenze: Giunti, Organizzazioni Speciali, 2011.

- Derogatis LR. Misuse of the

symptom checklist 90. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983; 40(10):1152-3. doi:

10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790090114025. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790090114025 PMid:6625866

- Apolone

G, Mosconi P. The Italian SF-36 Health Survey: translation, validation

and norming. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998; 51(11):1025-36. doi:

10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00094-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00094-8 PMid:9817120

- Pruneti

C. The « P Stress Questionnaire »: A new tool for the evaluation of

stress-related behaviours, European Journal of Clinical Psychology and

Psychiatry,2011;VI, 3: 1-37.

- Pilowsky

I, Spence ND. Manual for the illness behavior questionnaire (IBQ), (3rd

Edn). Adelaide: University of Adelaide, 1994.

- Gringeri

A, Leissinger C, Cortesi PA, Jo H, Fusco F, Riva S, Antmen B, Berntorp

E, Biasoli C, Carpenter S, Kavakli K, Morfini M, Négrier C, Rocino A,

Schramm W, Windyga J, Zülfikar B, Mantovani LG. Health-related quality

of life in patients with haemophilia and inhibitors on prophylaxis with

anti-inhibitor complex concentrate: results from the Pro-FEIBA study.

Haemophilia, 2013; 19(5):736-43. doi: 10.1111/hae.12178. https://doi.org/10.1111/hae.12178 PMid:23731246

- Cuesta-Barriuso

R, Torres-Ortuño A, Nieto-Munuera J, López-Pina JA. Quality of Life,

Perception of Disease and Coping Strategies in Patients with Hemophilia

in Spain and El Salvador: A Comparative Study. Patient Prefer

Adherence. 2021; 15:1817-1825. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S326434. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S326434 PMid:34456562 PMCid:PMC8387734

- Bago

M, Butkovic A, Faganel Kotnik B, Prga I, Bačić Vrca V, Zupančić Šalek

S, Preloznik Zupan I. Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with

Haemophilia and Its Association with Depressive Symptoms: A Study in

Croatia and Slovenia. Psychiatr Danub. 2021; 33(3):334-341. doi:

10.24869/psyd.2021.334. https://doi.org/10.24869/psyd.2021.334 PMid:34795175

- Pinto

PR, Paredes AC, Moreira P, Fernandes S, Lopes M, Carvalho M, Almeida A.

Emotional distress in haemophilia: Factors associated with the presence

of anxiety and depression symptoms among adults. Haemophilia. 2018;

24(5):e344-e353. doi: 10.1111/hae.13548. https://doi.org/10.1111/hae.13548 PMid:30004620

- Banchev

A, Batorova A, Faganel Kotnik B, Kiss C, Puras G, Zapotocka E,

Zupancic-Salek S; Patient Advocacy Group. A Cross-National Survey of

People Living with Hemophilia: Impact on Daily Living and Patient

Education in Central Europe. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2021;

15:871-883. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S303822 PMid:33953547 PMCid:PMC8091596

- Kempton

CL, Makris M, Holme PA. Management of comorbidities in haemophilia.

Haemophilia. 2021; 27 Suppl 3:37-45. doi: 10.1111/hae.14013. https://doi.org/10.1111/hae.14013 PMid:32476243

- Zawilska

K, Podolak-Dawidziak M. Therapeutic problems in elderly patients with

hemophilia. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2012; 122(11):567-76. https://doi.org/10.20452/pamw.1466 PMid:23207414

- Franzoni

F, Scarfò G, Guidotti S, Fusi J, Asomov M, Pruneti C. Oxidative Stress

and Cognitive Decline: The Neuroprotective Role of Natural

Antioxidants. Front Neurosci. 2021; 15:729757. doi:

10.3389/fnins.2021.729757. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2021.729757 PMid:34720860 PMCid:PMC8548611

- Sumari-de

Boer IM, Sprangers MA, Prins JM, Nieuwkerk PT. HIV stigma and

depressive symptoms are related to adherence and virological response

to antiretroviral treatment among immigrant and indigenous HIV infected

patients. AIDS Behav. 2012; 16(6):1681-9. doi:

10.1007/s10461-011-0112-y. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-011-0112-y PMid:22198315 PMCid:PMC3401302

- Torres-Ortuño

A, Cuesta-Barriuso R, Nieto-Munuera J, Galindo-Piñana P, López-Pina JA.

Coping strategies in young and adult haemophilia patients: A tool for

the adaptation to the disease. Haemophilia. 2019;25(3):392-397 https://doi.org/10.1111/hae.13743 PMid:30994251

- Carrico

AW, Bangsberg DR, Weiser SD, Chartier M, Dilworth SE, Riley ED.

Psychiatric correlates of HAART utilization and viral load among

HIV-positive impoverished persons. AIDS. 2011; 25(8):1113-8. doi:

10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283463f09. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283463f09 PMid:21399478 PMCid:PMC3601574

- Limperg

PF, Maurice-Stam H, Heesterbeek MR, Peters M, Coppens M, Kruip MJHA,

Eikenboom J, Grootenhuis MA, Haverman L. Illness cognitions associated

with health-related quality of life in young adult men with

haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2020; 26(5):793-799. doi: 10.1111/hae.14120. https://doi.org/10.1111/hae.14120 PMid:32842171

- Jones

QJ, Garsia RJ, Wu RT, Job RF, Dunn SM. A controlled study of anxiety

and morbid cognitions at initial screening for human immunodeficiency

virus (HIV) in a cohort of people with haemophilia. J Psychosom Res.

1995;39(5):597-608. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)00147-2. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3999(94)00147-2 PMid:7490694

- Trindade

GC, Viggiano LGL, Brant ER, Lopes CAO, Faria ML, Ribeiro PHNS, Silva

AFDC, Souza DMR, Lopes AF, Soares JMA, Pinheiro MB. Evaluation of

quality of life in hemophilia patients using the WHOQOL-bref and

Haemo-A-Qol questionnaires. Hematol Transfus Cell Ther. 2019;

41(4):335-341. doi: 10.1016/j.htct.2019.03.010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.htct.2019.03.010 PMid:31409581 PMCid:PMC6978543

- Yuvaraj

A, Mahendra VS, Chakrapani V, Yunihastuti E, Santella AJ, Ranauta A,

Doughty J. HIV and stigma in the healthcare setting. Oral Dis. 2020; 26

Suppl 1:103-111. doi: 10.1111/odi.13585. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.13585 PMid:32862542

- Nanni

MG, Caruso R, Mitchell AJ, Meggiolaro E, Grassi L. Depression in HIV

infected patients: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015; 17(1):530. doi:

10.1007/s11920-014-0530-4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-014-0530-4 PMid:25413636

- Dalgard

O, Egeland A, Skaug K, Vilimas K, Steen T. Health-related quality of

life in active injecting drug users with and without chronic hepatitis

C virus infection. Hepatology. 2004; 39(1):74-80. doi:

10.1002/hep.20014. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.20014 PMid:14752825

- Cosentino

C, Sgromo D, Merisio C, Berretta R, Pruneti C. Psychophysiological

Adjustment to Ovarian Cancer: Preliminary Study on Italian Women

Condition. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback.. 2018; 43(2):161-168. doi:

10.1007/s10484-018-9395-3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-018-9395-3 PMid:29926266

- Pruneti

C. Guidotti S. Cognition, Behavior, Sexuality, and Autonomic Responses

of Women with Hypothalamic Amenorrhea. BrainSci. 2022;12:1448. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12111448 PMid:36358374 PMCid:PMC9688049

- De

Vincenzo F, Cosentino C, Quinto RM, Di Leo S, Contardi A, Guidotti S,

Iani L, Pruneti C. Psychological adjustment and heart rate variability

in ovarian cancer survivors. Mediterr J Clin Psychol. 2022; 10. https://doi.org/10.13129/2282-1619/mjcp-3318.

- Morris

G, Reiche EMV, Murru A, Carvalho AF, Maes M, Berk M, Puri BK. Multiple

Immune-Inflammatory and Oxidative and Nitrosative Stress Pathways

Explain the Frequent Presence of Depression in Multiple Sclerosis. Mol

Neurobiol. 2018; 55(8):6282-6306. doi: 10.1007/s12035-017-0843-5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-017-0843-5 PMid:29294244 PMCid:PMC6061180

- Pruneti

C, Guidotti S. Physiological Stress as Risk Factor for Hypersensitivity

to Contrast Media: A Narrative Review of the Literature and a Proposal

of Psychophysiological Tools for Its Detection. Physiologia. 2022;

2:55-65. https://doi.org/10.3390/ physiologia2030006. https://doi.org/10.3390/physiologia2030006

[TOP]