Mariasanta Napolitano1*, Nicola Vianelli2*, Lisanna Ghiotto3, Silvia Cantoni4, Giuseppe Carli5, Monica Carpenedo6, Valentina Carrai7, Ugo Consoli8, Gaetano Giuffrida9, Elisa Lucchini10, Elena Rossi11, Cristina Santoro12 and Francesco Rodeghiero3.

1

Department of Health Promotion, Mother and Child Care, Internal

Medicine and Medical Specialties (PROMISE), University of Palermo,

Reference Regional Center for Thrombosis and Hemostasis, Hematology

Unit, Palermo.

2 Institute of Hematology "Seràgnoli", IRCCS Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria of Bologna, Bologna.

3 Hematology Project Foundation, Vicenza, affiliated to Department of Hematology, "S. Bortolo" Hospital, Vicenza.

4 Department of Hematology and Oncology, Niguarda Cancer Center, ASST "Grande Ospedale Metropolitano," Niguarda Hospital, Milan.

5 Department of Hematology, "S. Bortolo" Hospital, Vicenza.

6 Hematology and Transplantation Unit, "S. Gerardo" Hospital, Monza.

7 Hematology Unit, A.O.U. “Careggi”, Florence.

8 Division of Hematology, ARNAS Garibaldi, Catania

9 Division of Hematology, AOU “Policlinico G. Rodolico-San Marco”, Catania.

10 Hematology Unit, Azienda Sanitaria Universitaria Giuliano Isontina, Trieste.

11 Section

of Hematology, Department of Radiological and Hematological Sciences,

Catholic University, Fondazione Policlinico A. Gemelli IRCCS, Rome.

12 Hematology Unit, Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Policlinico Umberto I, Rome.

* The author equally contributed to the paper.

Correspondence to: Francesco

Rodeghiero, Hematology Project Foundation, Contrà San Francesco 41,

36100 Vicenza - Italy Tel. +39 0444 751731. E-mail:

rodeghiero@hemato.ven.it

Published: March 1, 2023

Received: December 22, 2022

Accepted: February 19, 2023

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2023, 15(1): e2023019 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2023.019

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Background:

Two thrombopoietin receptor agonists (TPO-RA), romiplostim and

eltrombopag, are currently widely adopted as second-line ITP therapy

even in the absence of robust evidence on their comparative advantages

over rituximab or splenectomy or their preferential use in some

specific clinical contexts.

Methods: An online survey was distributed between May 2021 and June 2021 to collect standardized information on TPO-RA use in Italy.

Results:

Eighty-eight hematologists from 79 centers completed the survey.

Eighty-four percent would use TPO-RA earlier than formally indicated,

without a preference for young or elderly in 82% of respondents. No

clear preference for either romiplostim or eltrombopag was indicated.

Seventy-two percent would use TPO-RA in young patients aiming at a

complete response followed by tapering, a strategy considered by only

16% in the elderly. Switching between the two agents was considered

appropriate in case of insufficient response or intolerance. Tapering

schedule by reducing the dosage and prolonging the intervals between

administrations was preferred by 73% of respondents. TPO-RA was

considered a risk factor for thrombosis by only 35%, and 94% would

administer TPO-RA in elderly patients also in the presence of other

thrombotic risk factors. Thirty-three percent of respondents would

withdraw TPO-RA in case of thrombosis. The TPO-RA administration has

been reported to be preferred over anti-CD20 or splenectomy by about

half of the participants due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusions: Significant

discrepancies in TPO-RA use emerged from the survey, and participants

would appreciate consensus-based specific guidance on the practical use

of TPO-RA.

|

Introduction

Immune

thrombocytopenia (ITP) is an autoimmune disease characterized by

isolated thrombocytopenia with a platelet count <100x109/L

caused by a dysregulation of the immune response, which promotes the

production of autoreactive antibodies and the proliferation of abnormal

T-cells, leading to the destruction of circulating platelets and a

defective megakaryopoiesis, unable to compensate the continued

increased platelet consumption.[1] Where other causes

of thrombocytopenia have been excluded, ITP is defined as primary

(simply referred to as ITP in this paper) and, based on its duration,

is classified as newly diagnosed (< 3 months), persistent

(3–12 months), and chronic (> 12 months).[2] This latter form is the most prevalent in adults, with around 70-80% of new cases evolving into chronicity.[3] Recently, an International Consensus Report (ICR)[4] and ASH evidence-based guidelines[5]

have defined the aims of ITP treatment and the role of the main

therapeutical agents, including corticosteroids, as the preferred

option for first-line treatment and rituximab, thrombopoietin receptor

agonists (TPO-RA) and splenectomy, variably indicated as second- or

third-line treatments. Both documents have largely adopted the

terminology, definitions, and outcome criteria proposed by an

International Working Group more than a decade ago[2] and are still most frequently used in investigator-driven collaborative studies,[6] thus facilitating the comparison among the different clinical scenarios and related outcomes.

The

overall picture emerging from available real-life studies is one of

heterogeneity, particularly beyond the initial corticosteroids

treatment, which is unanimously recommended by the most recent

international guidelines for newly diagnosed patients with a platelet

count of <20-30x109/L even if

asymptomatic or even at higher platelet counts in the presence of

bleeding manifestations. However, since the clinical benefit often is

transient and adjunctive therapies are needed, both ICR and ASH

guidelines[4,5] recommend keeping the corticosteroid

administration as short as possible and not prolonged beyond 6-8 weeks,

including tapering. Unfortunately, this recommendation is often

unattended in common practice.[7,8] Hence, there is a

major interest in analyzing the attitude of treating physicians in the

management of corticosteroid-refractory patients at a time when TPO-RA,

romiplostim and eltrombopag, introduced in clinical practice more than

10 years ago,[9] allowed to postpone or even avoid splenectomy,[10-14]

with its significant burden of morbidity, mainly secondary to

infections and thrombosis. To some extent, TPO-RA are also replacing

rituximab due to its limitation in inducing long-term responses.

Nevertheless,

after the advent of TPO-RA, new challenges and several issues regarding

this therapeutic option is still debated, including their potential to

increase the thrombotic risk of ITP[15] and other

relevant practical management aspects. These latter include selecting

the most appropriate TPO-RA, reaching and maintaining optimal platelet

count before attempting tapering or discontinuation, switching between

TPO-RA agents, and use in patients with advanced age and/or concomitant

risk factors for thrombosis.[16-19] Indeed, a

tailored approach in the management of ITP involves an accurate

evaluation of many aspects, such as actual platelet count, bleeding

symptoms, duration of the disease, lifestyle, age, thrombotic risk,

potential adverse events, potential drug interactions, and response to

previous treatments.

TPO-RA use in real-life clinical practice

has been the subject of limited investigations, with some national

surveys showing variable attitudes toward their use.[16,20]

In Italy, limited unpublished information from national or regional

meetings sponsored by interested companies reverberated the opinion of

a widespread but not uniform use of TPO-RA. To further expand the

knowledge of the real-life use of these agents, the Hematology Project

Foundation (HPF) promoted and founded a nationwide survey aimed at

obtaining a more comprehensive understanding of the real-life use of

TPO-RA (romiplostim and eltrombopag) in an unbiased and independent

manner. The survey was designed to collect standardized data based on

self-reported information by hematologists treating ITP of adults

concerning the TPO-RA use in the various clinical scenarios encountered

by practicing hematologists.

We report the results emerging from

this nationwide survey involving 88 respondents and discuss them in the

light of approved indications, international guidelines, other national

reports, and literature data.

Material and Methods

Hematologists

charged for managing ITP in adults were identified through the largest

Italian hematology collaborative network maintained at GIMEMA

Foundation (https://www.gimema.it/la-fondazione/centri-gimema/),

which includes all private and public Italian hematological centers.

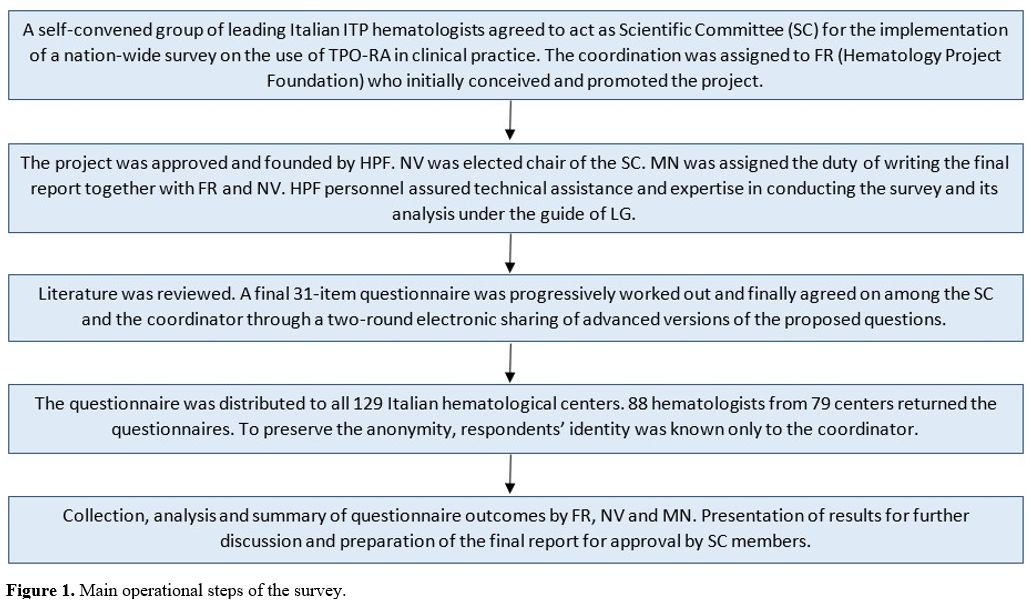

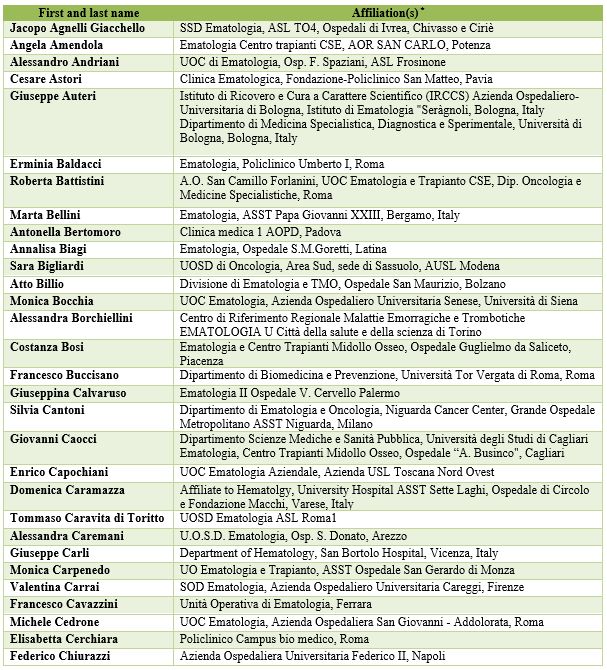

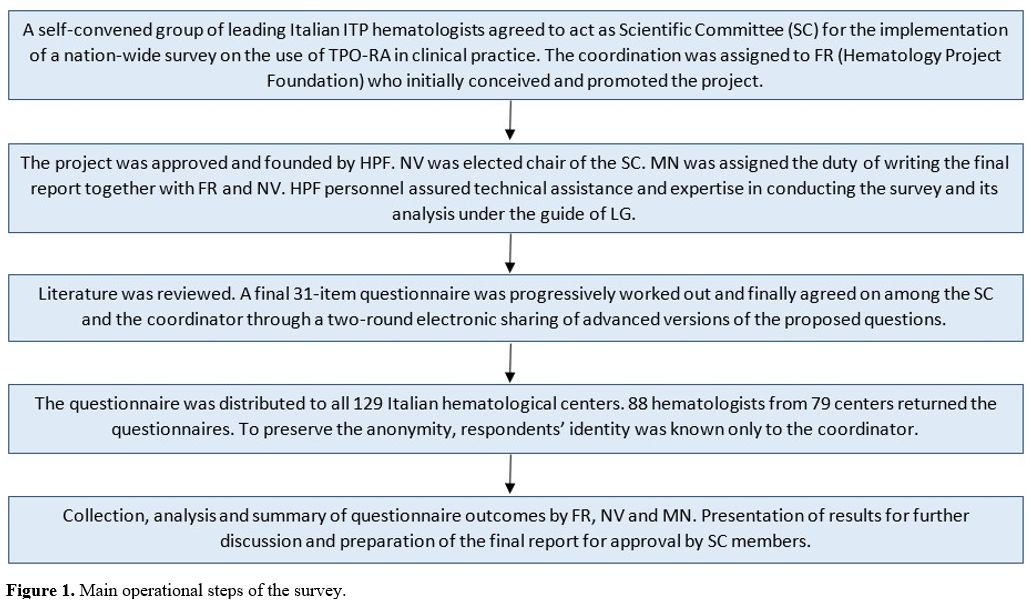

All of them were invited to complete a cross-sectional survey. Figure 1 shows the several operational steps of the whole process, from its conception to final analysis.

|

- Figure 1. Main operational steps of the survey.

|

The project was conceived and coordinated by FR (HPF) and included several phases (Figure 1).

A scientific committee chaired by NV and including 12 hematologists

(SC, GC, MC, VC, UC, GG, EL, MN, ER, CS, FR, NV) with recognized

experience in the treatment of ITP was convened to prepare a

provisional list of questions. Through a two-round sharing of advanced

versions of the proposed questions, the scientific committee and the

coordinator developed a final 31-item questionnaire with due attention

to equipoise, completeness, and clarity of questions. Survey items were

close-ended or multiple choice-style questions, with, in some cases,

open-ended questions for specifications. Each set of questions on a

particular topic always included also open-ended questions. The

respondent's anonymity was preserved so that only the coordinator knew

his/her identity.

Survey items addressed the following 9

domains: timing of administration of TPO-RA and preferred agent;

modality and purpose of treatment in young and elderly patients;

parameters evaluated to discontinue treatment in young and elderly

patients; switching and tapering of TPO-RA; perceived thrombotic risk

associated with TPO-RA; perceived incidence of thrombosis during TPO-RA

treatment and its management; TPO-RA during COVID-19 pandemic;

administration of TPO-RA in combination or associated with other

agents; selected challenging scenarios (including treatment duration,

patients requesting to change treatment with TPO-RA, pregnancy, and

detection of antiphospholipid antibodies).

The survey was conducted and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture),[21]

a secure web-based data capture software, and distributed in May 2021,

with a reminder sent to non-respondents after 2 and 3 weeks. The survey

was distributed exclusively by the coordinator, with technical support

from LG (HPF). No incentives were offered to participants. All

participants gave consent to the use of their data. Since no

institutional informations were required, institutional permission to

participate was not required. The list of participants is reported in Appendix 2.

Received

questionnaires were preliminarily examined by the coordinator to check

for inconsistencies and require further information. Subsequently,

expert personnel at HPF (LG) summarized the answers as percentages and

collected all text comments in an orderly manner for examinations by

the coordinator and scientific committee chair. All analysis and

graphics were carried out using R (v4.1.0).

Finally, a draft paper

was prepared by FR, NV, MN, and LG and circulated among all panel

members for further revision and final approval.

Results

A

total of 88 hematologists from 79 centers, among the 129 identified,

responded to the survey and returned the questionnaire, with only 2%

leaving partially unanswered questions. Therefore, all respondents were

considered participants and included in the analysis.

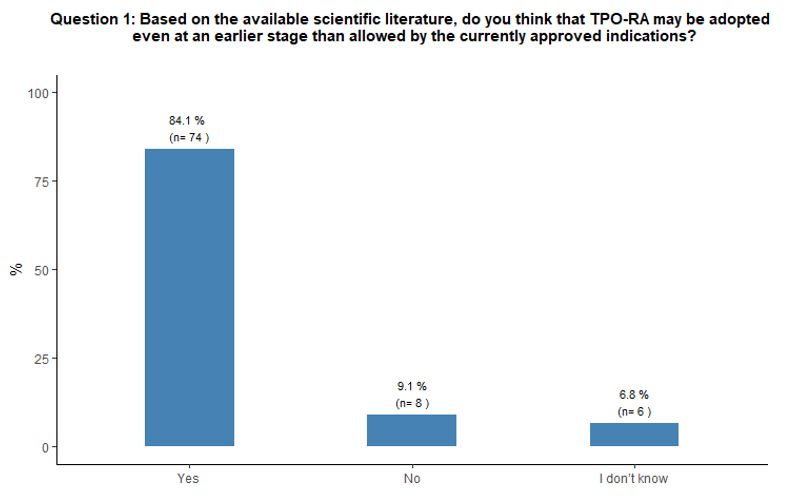

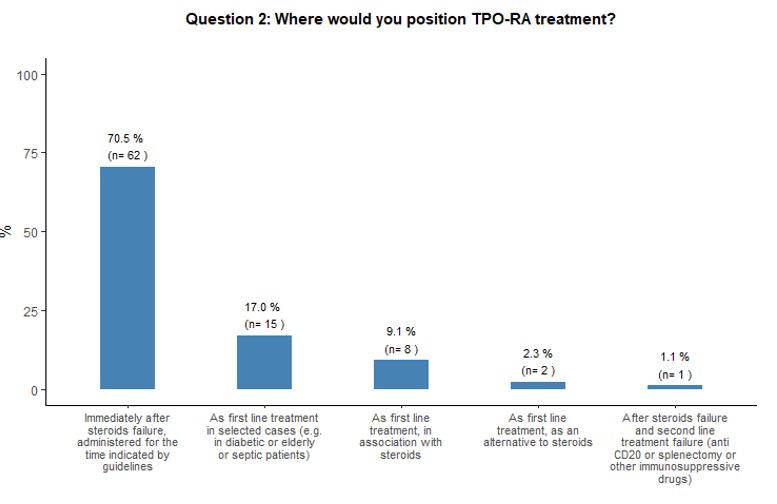

Timing of administration of TPO-RA and preferred agent.

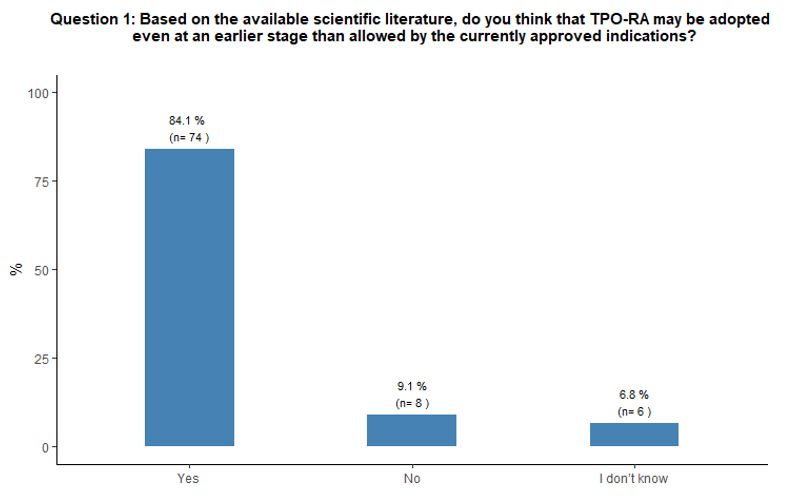

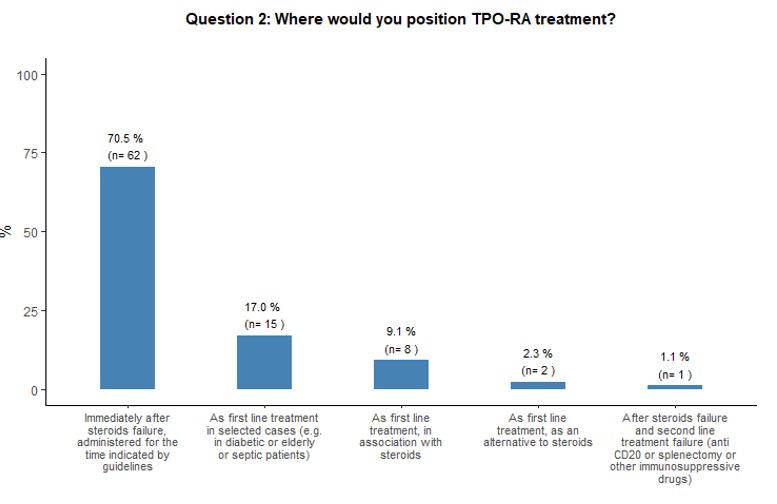

As to the optimal timing of TPO-RA administration and preferred agent,

84% of participants reported that they would administer either

romiplostim or eltrombopag at an earlier stage than defined by the

specifications of the marketing authorization of EMA, which, at the

time of this survey, still limited the use of eltrombopag, but not of

romiplostim, only after at least 6 months from diagnosis at variance

with the latest marketing authorizations.[22,23] More

precisely, the majority (71%) would prescribe them immediately after

steroids failure, and 17% propose TPO-RA administration as front-line

treatment in specific subsets of patients (e.g., diabetic, septic, or

very aged subjects). See questions 1 and 2 in Appendix 1.

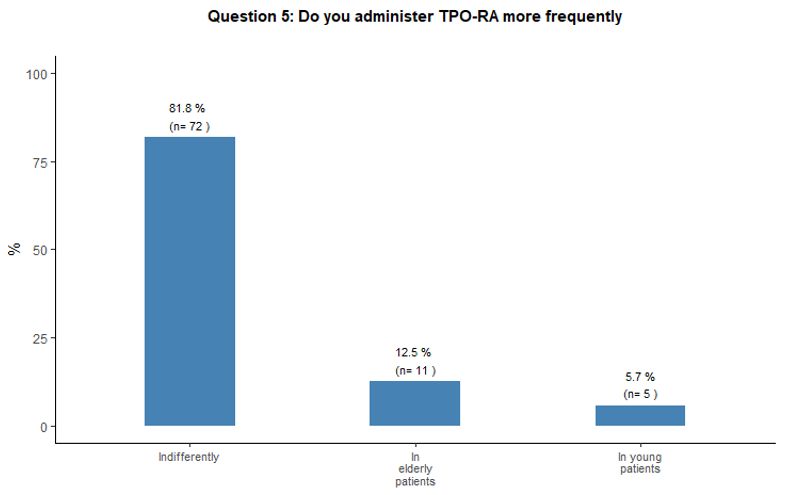

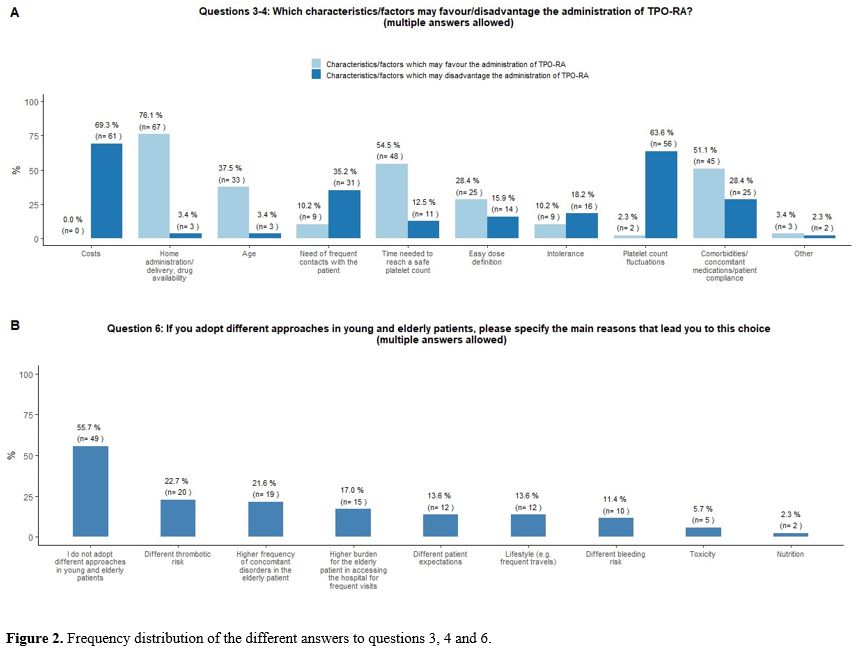

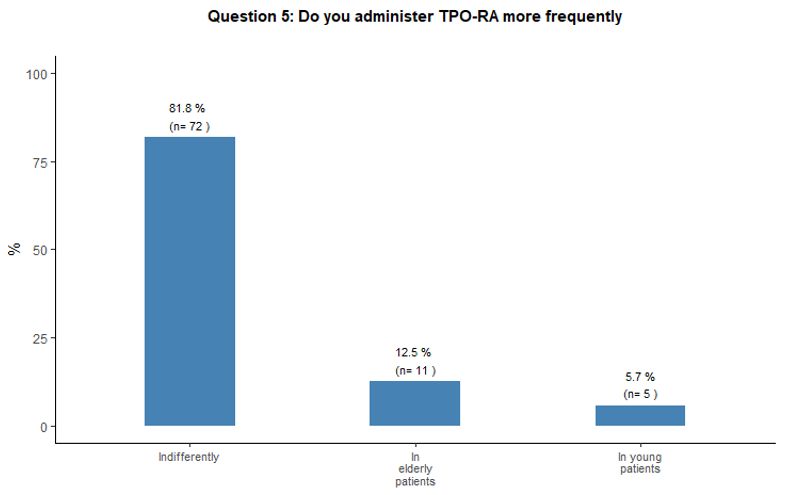

Modality and purpose of treatment in young and elderly patients.

Eighty-two percent of participants in the survey stated that they would

indifferently use romiplostim and eltrombopag, with the same frequency

among young and elderly patients. See question 5 in Appendix 1.

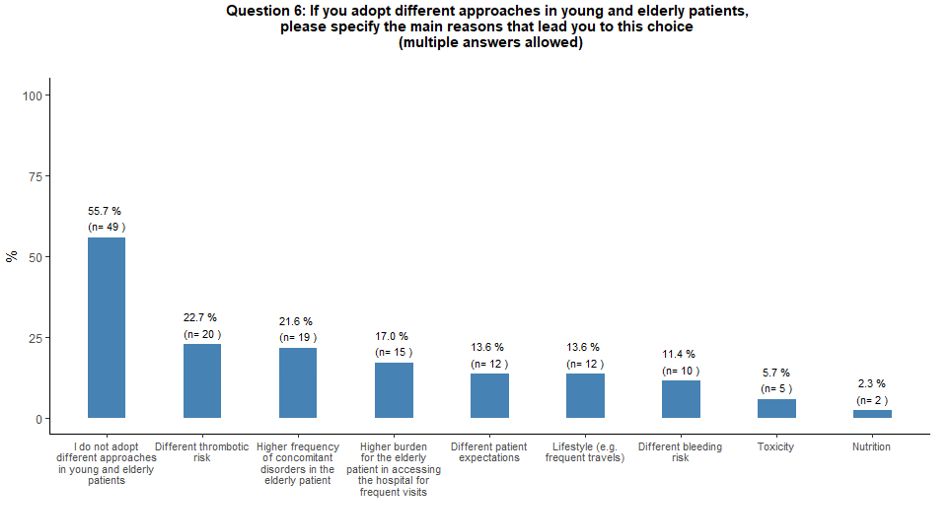

Fifty-six percent of the respondents reported that they do not adopt

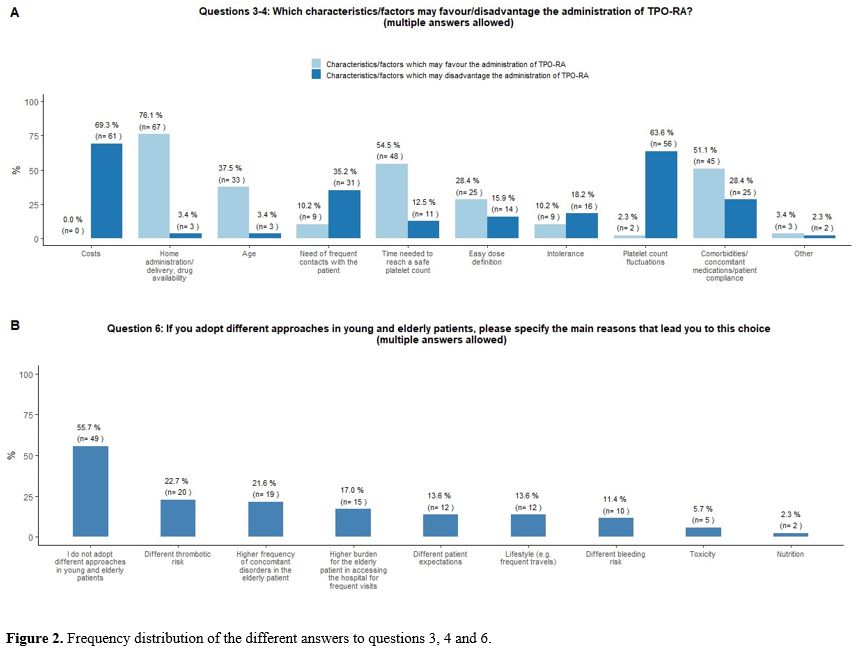

different approaches for young and elderly patients. On the contrary,

the perceived increased thrombotic risk, the higher incidence of

comorbidities in elderly patients, and the difficult hospital access

associated with advanced age were considered factors negatively

influencing the use of TPO-RA, respectively, for 23%, 22%, and 17% of

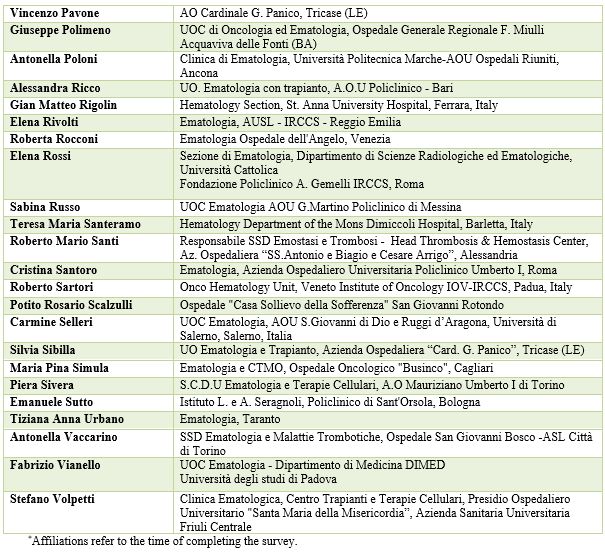

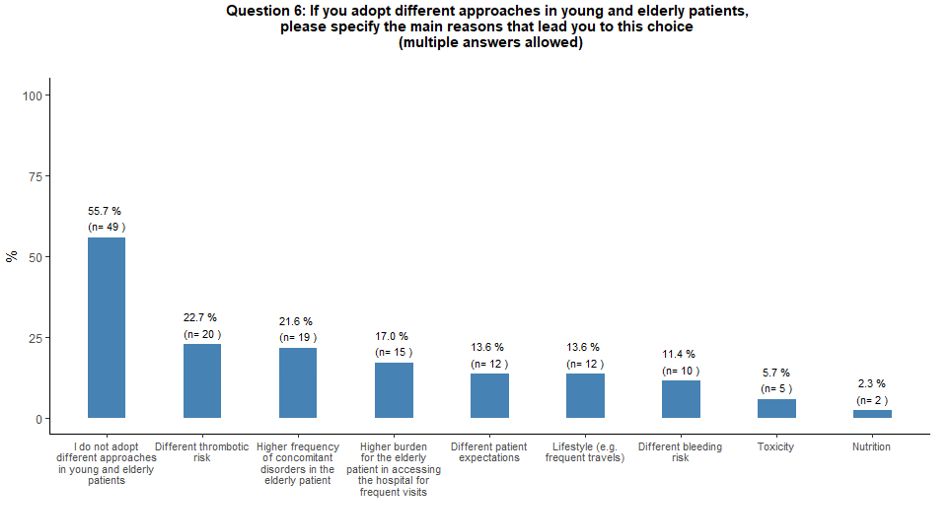

the respondents (Figure 2B).

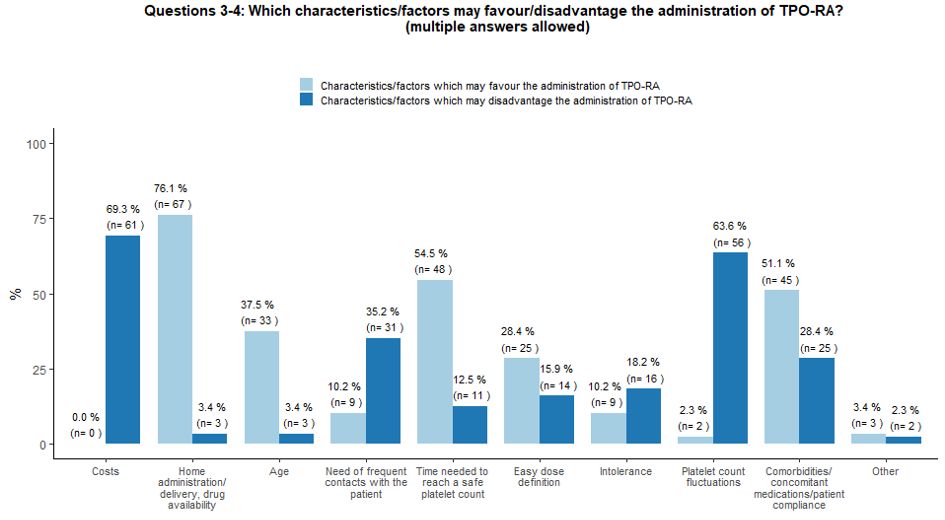

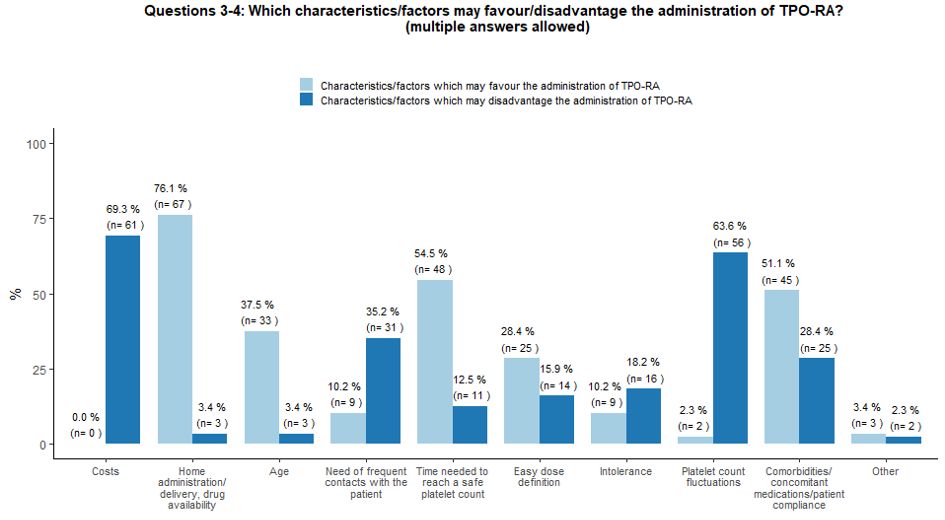

Several

specific factors may influence the choice of second-line therapies by

treaters. In our survey, the possibility of home administration, TPO-RA

manageability, the time interval needed to reach a safe platelet count,

comorbidities, certain concomitant therapies, and patient compliance

and age were considered the main factors which may favor the

administration of TPO-RA. On the contrary, costs, fluctuations in

platelet count levels, and the need for frequent contact with the

patient were identified as the main limitations of TPO-RA prescription (Figure 2A).

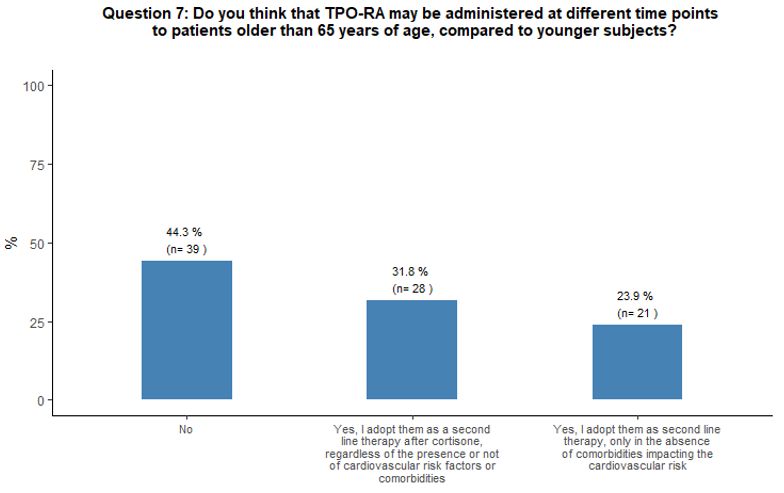

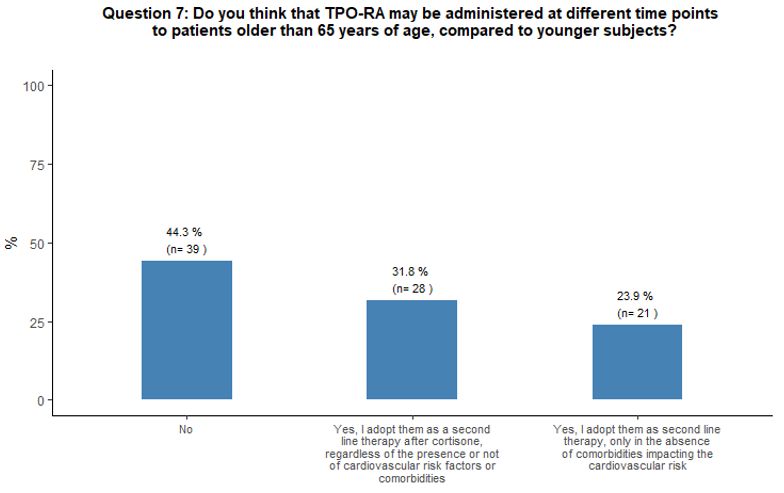

Forty-four

percent of participants did not consider initiating TPO-RA

administration at different time points (earlier or later) in patients

aged ≥ 65 years compared to the younger ones, 32% considered TPO-RA as

appropriate as a second line treatment option after cortisone in aging

subjects, independently from concomitant cardiovascular risk factors or

comorbidities and 24% considered TPO-RA use as a second line treatment

option only in the absence of comorbidities that may negatively impact

the cardiovascular system. See question 7 in Appendix 1.

|

- Figure 2. Frequency distribution of the different answers to questions 3, 4 and 6.

|

Parameters evaluated to discontinue treatment in young and elderly patients.

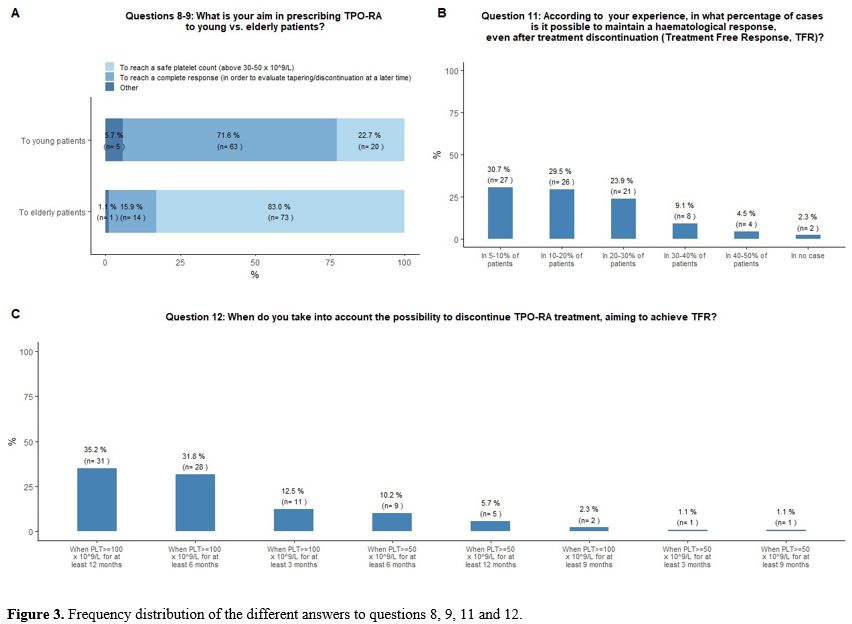

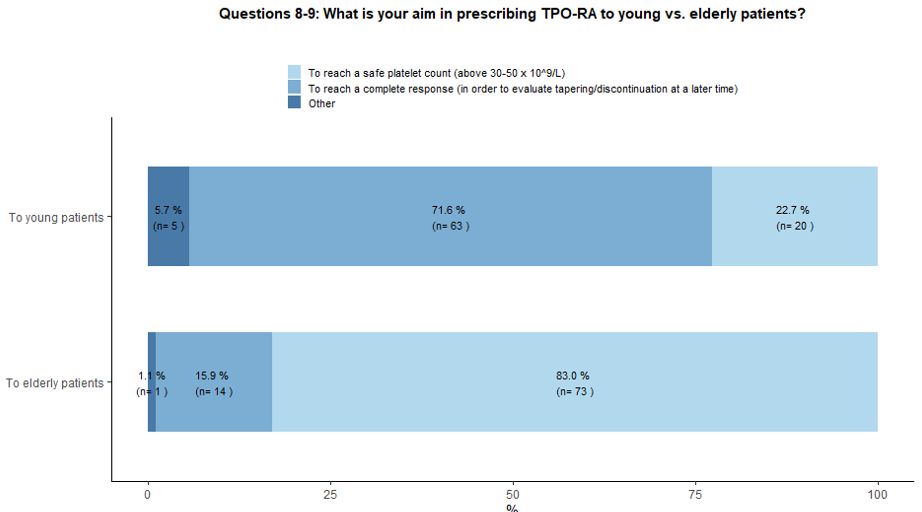

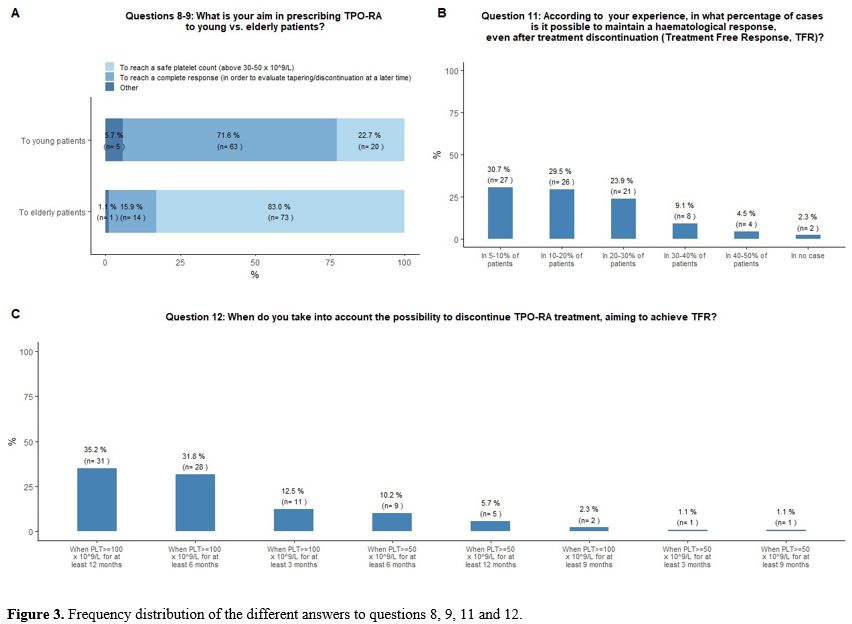

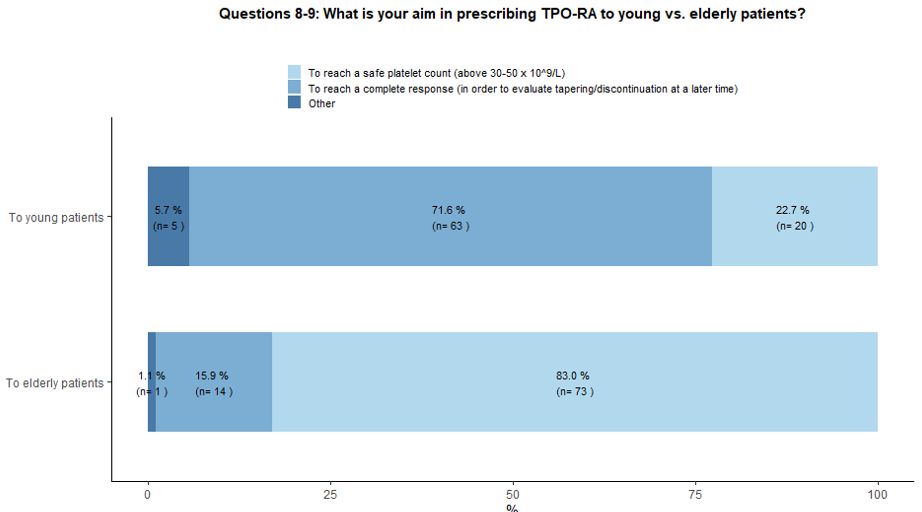

Seventy-two percent of participants would use TPO-RA in young patients

aiming at reaching a complete response followed by subsequent tapering

and treatment discontinuation in order to obtain a Treatment Free

Response (TFR); a couple of hematologists have highlighted the

possibility of administering TPO-RA as a bridge to splenectomy,

allowing patients to reach the chronic phase of the disease and then

receive vaccinations before splenectomy. On the other hand, in the

context of elderly patients, 83% of the involved hematologists would

use TPO-RA to obtain a stable and safe platelet count, and only 16%

would explore the possibility of reaching a complete response and

treatment discontinuation (Figure 3A).

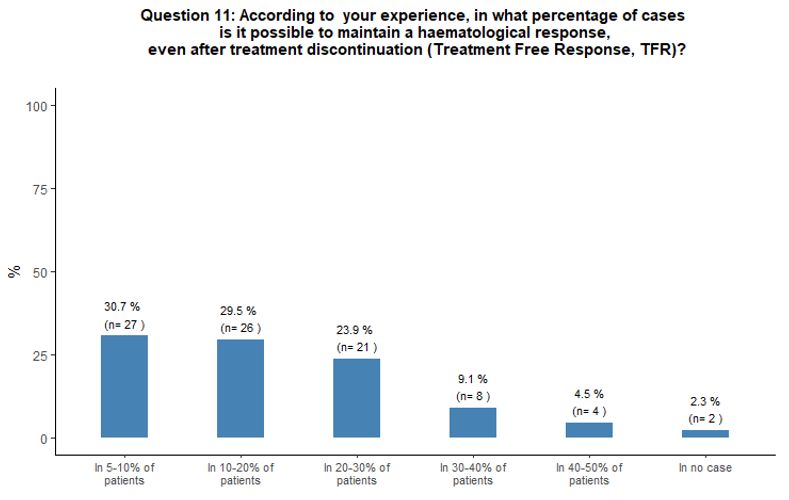

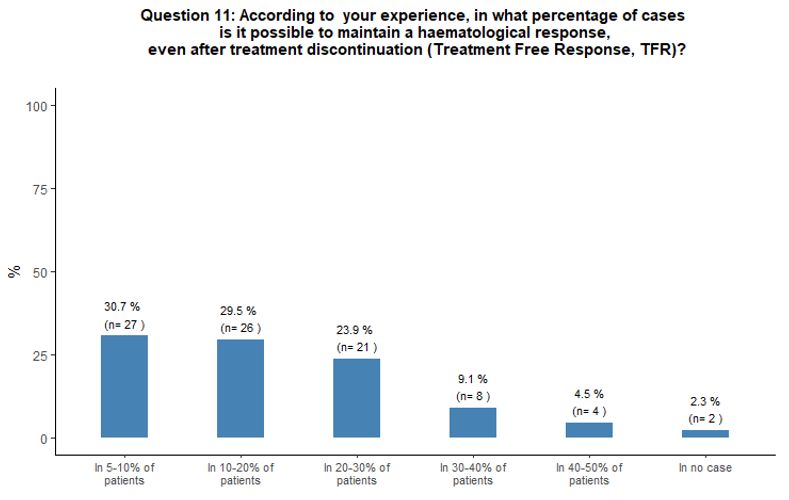

Approximately

one-third of participants reported having observed patients with TFR in

5-10% of their cases, while 30% and 24% of participants stated that in

their experience, a TFR was possible in 10-20% and 20-30% of cases

respectively (Figure 3B).

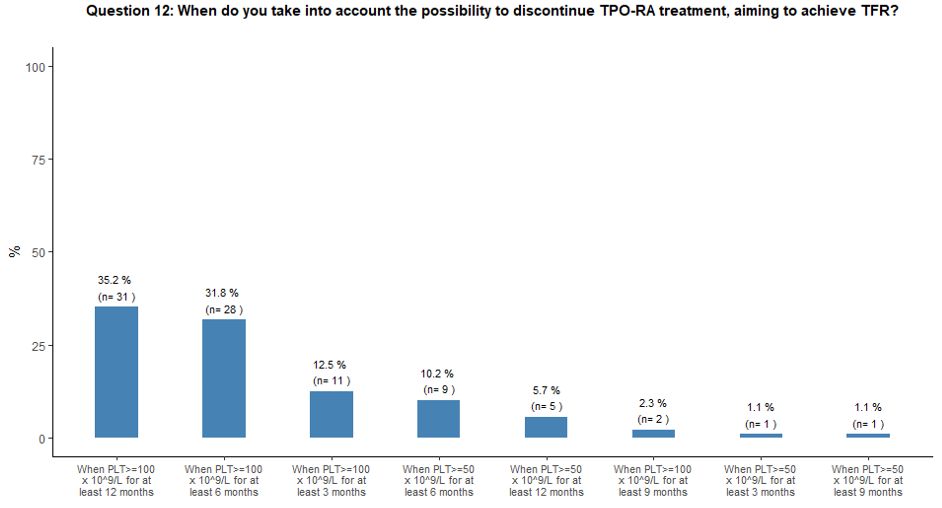

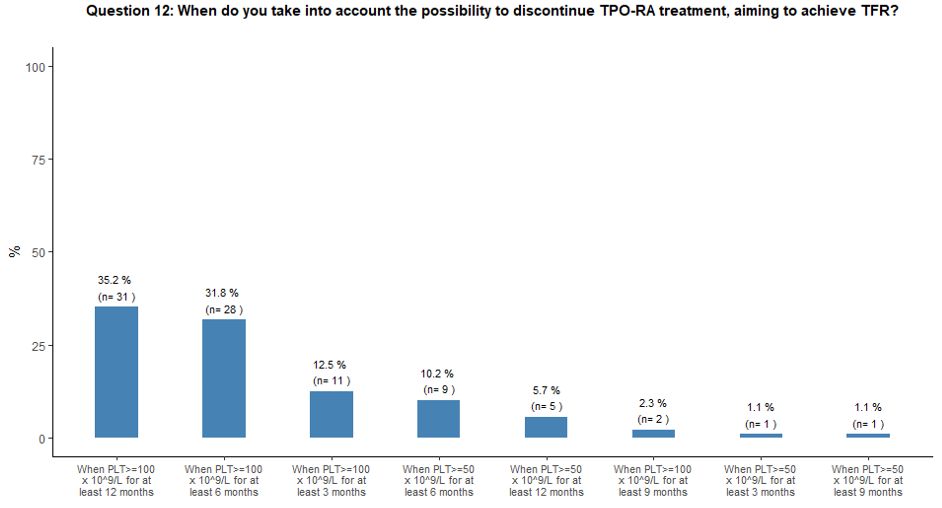

Thirty-five percent of participants would attempt to withdraw TPO-RA to obtain TFR when the platelet count is ≥ 100x109/L

for at least 12 months, while 32% and 13% would try to discontinue

TPO-RA treatment aiming to achieve TFR when the platelet count is

≥100x109/L for at least 6 and 3 months, respectively (Figure 3C).

|

- Figure 3. Frequency distribution of the different answers to questions 8, 9, 11 and 12.

|

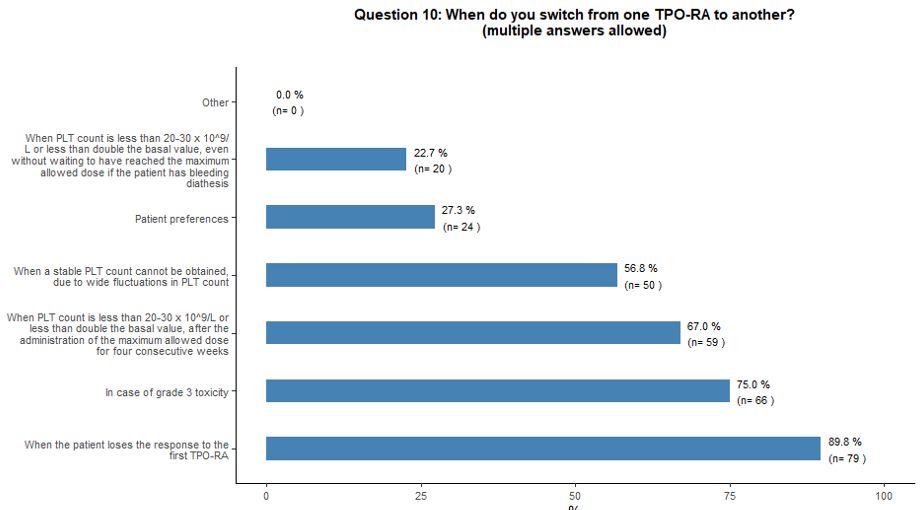

Switching and tapering of TPO-RA.

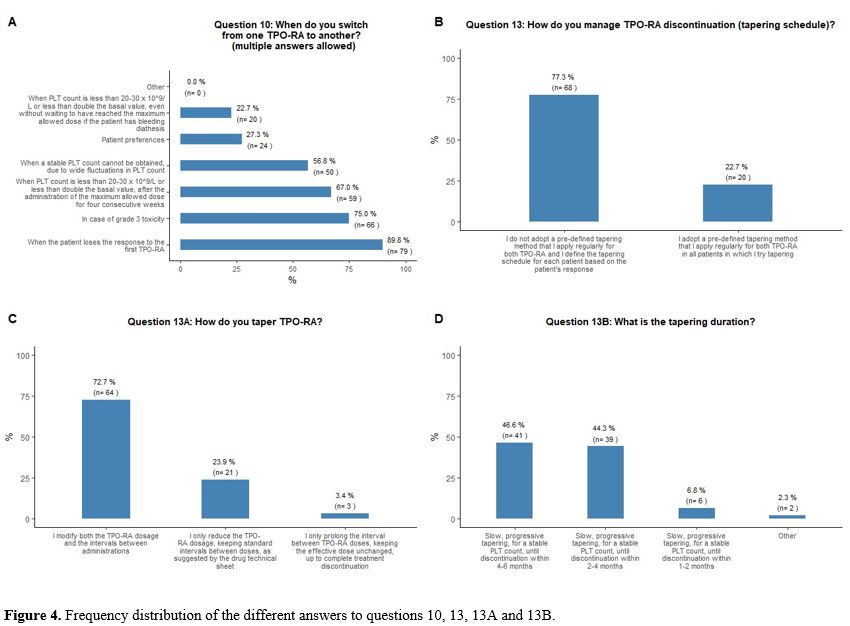

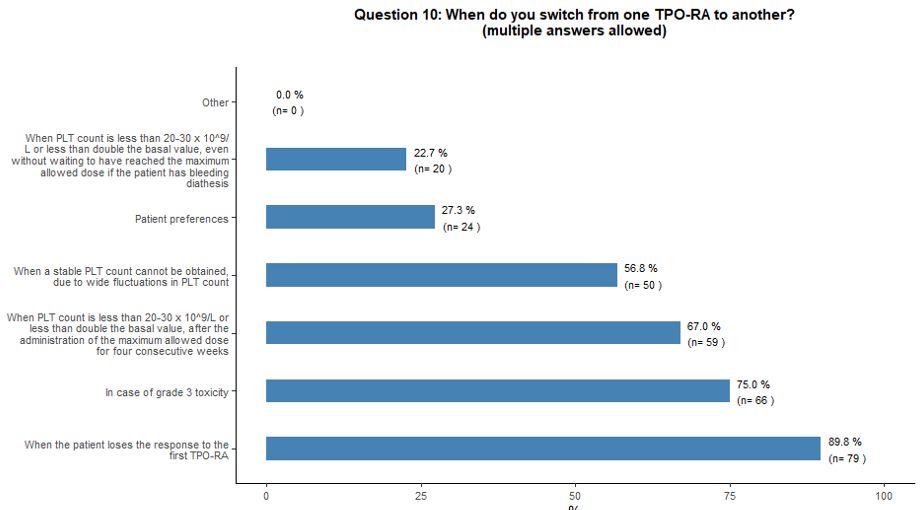

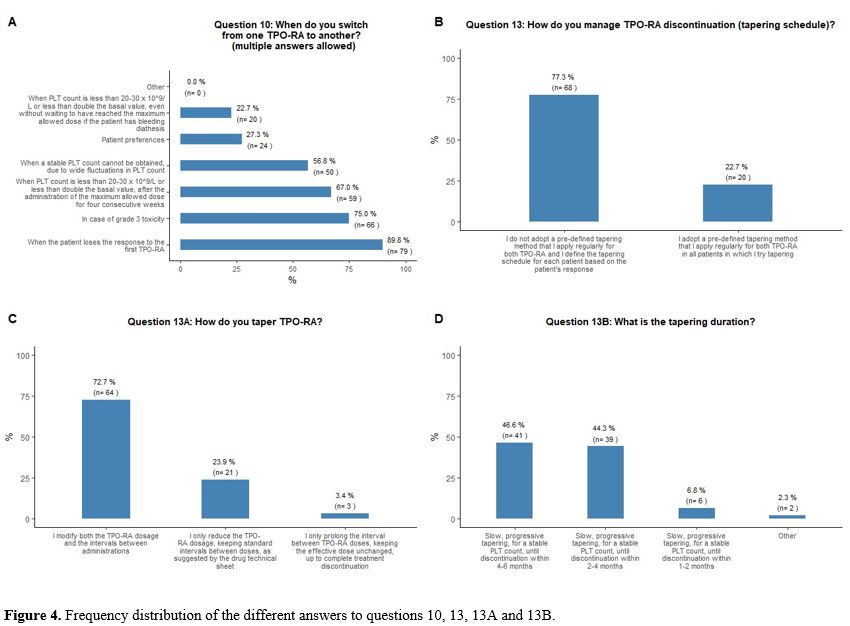

Regarding the main factors governing switching from one TPO-RA to the

other, the vast majority would consider this option in the following

clinical scenarios: loss of the response to the first TPO-RA (90%);

occurrence of significant toxicity (75%); failure to increase the

platelet count above 20-30x109/L or

to double the basal count despite the highest allowed dosage for four

consecutive weeks (67%); stable platelet count not reached, due to

large fluctuations in platelet counts (57%) (Figure 4A).

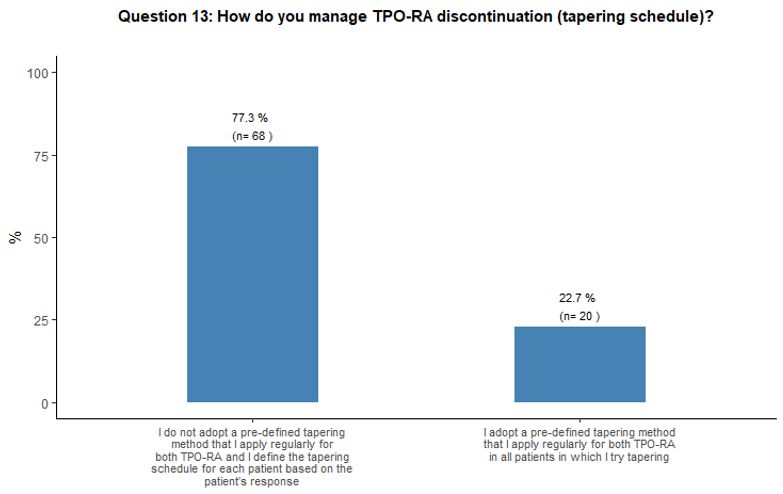

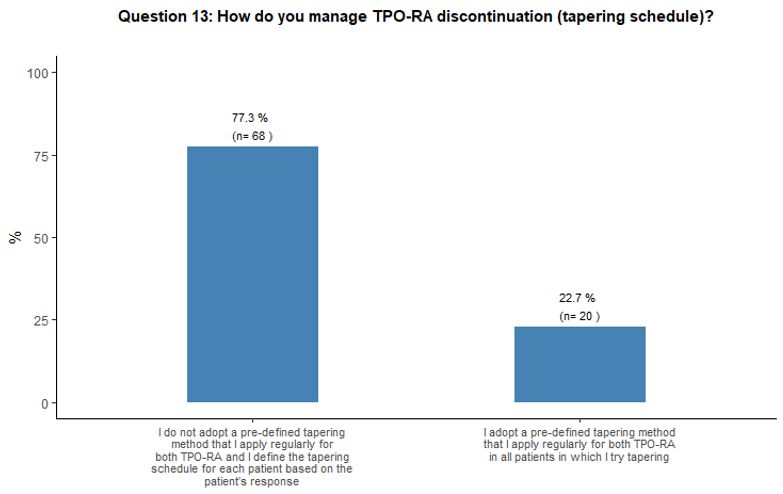

Regarding

the different tapering modalities, 77% of participants stated that they

would not adopt a pre-defined scheme that they apply consistently for

both TPO-RA but would prefer to decide on the basis of individual

patient platelet count trends (Figure 4B).

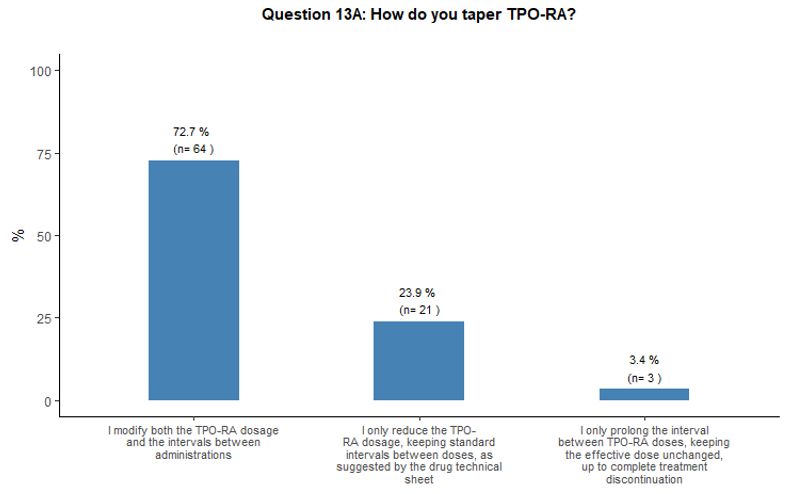

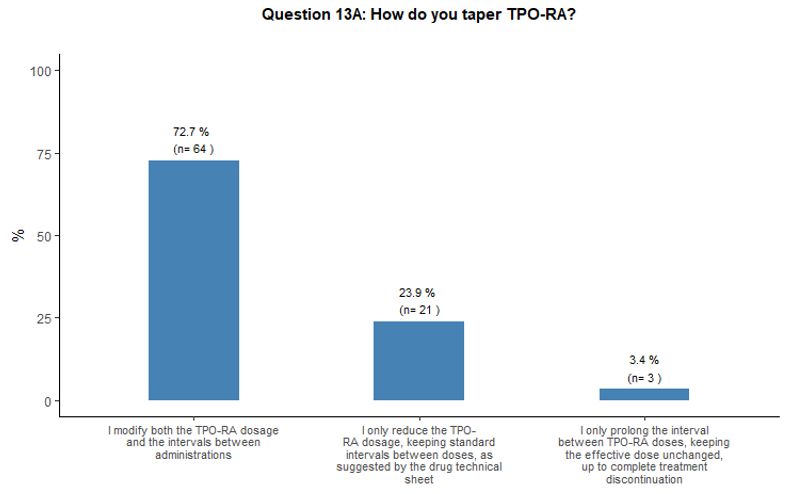

TPO-RA

tapering schedules would be mostly carried out by reducing the dosage

and prolonging the intervals between administrations (73% of

participants). Alternatively, some participants (27%) would prefer to

either reduce the dose or prolong the intervals (Figure 4C).

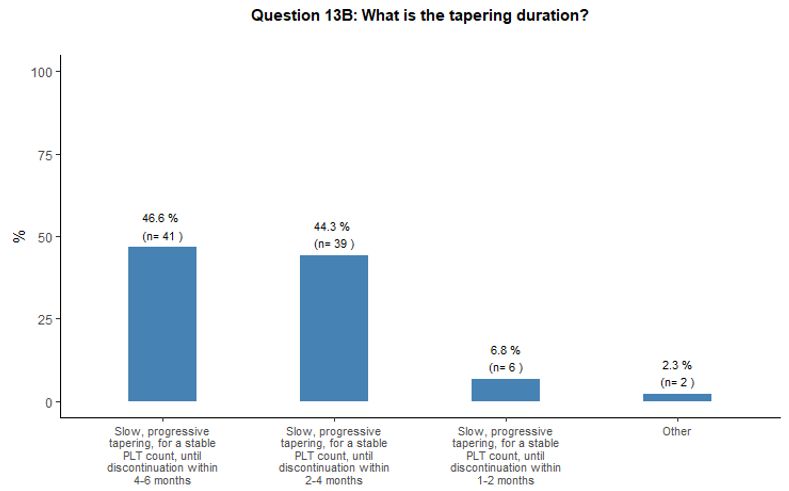

As

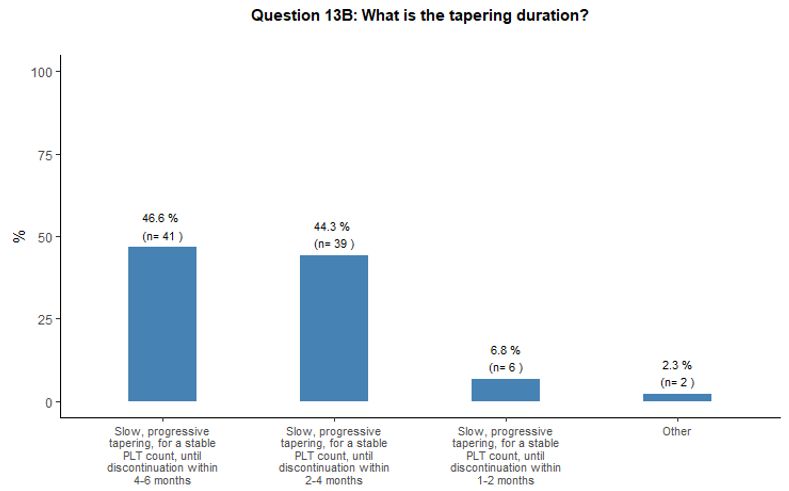

to the duration of the tapering phase, we observed some heterogeneity.

Forty-seven percent of participants would prefer a slow, progressive

tapering lasting up to 4-6 months until a stable platelet count is

maintained, before the suspension, while 44% would choose a more rapid

tapering within 2-4 months. A small proportion stated that they would

apply tapering within an even shorter time (1-2 months) or, on the

contrary, during a much longer time (up to twelve months) (Figure 4D).

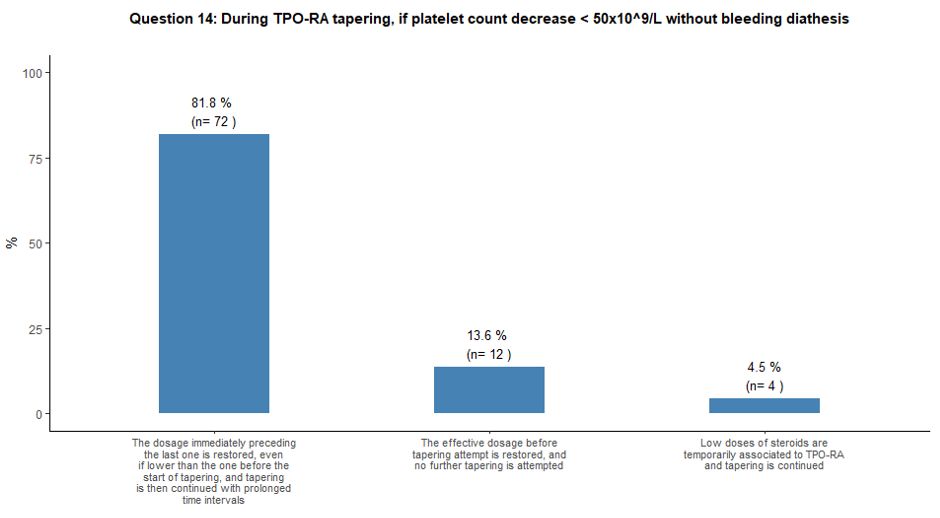

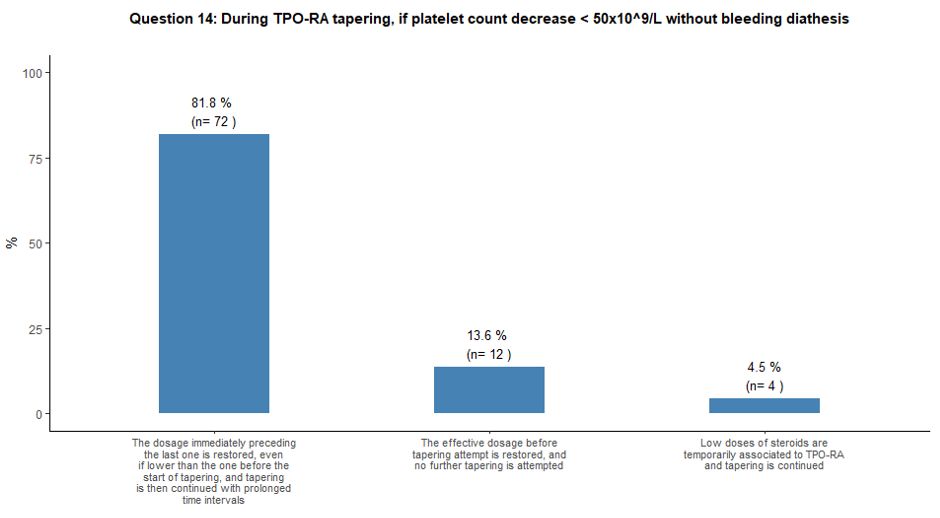

Once tapering of TPO-RA is initiated, it would be strictly guided by

platelet count. Several tapering choices were proposed when platelets

decreased below 50x109/L without

bleeding diathesis. Most participants (82%) indicated that they would

prefer to restore the drug dosage immediately preceding the last one

and slow down the tapering phase. On the other hand, 14% of

participants would prefer to restore the pre-tapering effective TPO-RA

dosage without further attempting another tapering. Finally, a small

number of participants (4%) would temporarily associate low doses of

steroids to TPO-RA while continuing the planned tapering schedule. See

question 14 in Appendix 1.

|

- Figure 4. Frequency distribution of the different answers to questions 10, 13, 13A and 13B.

|

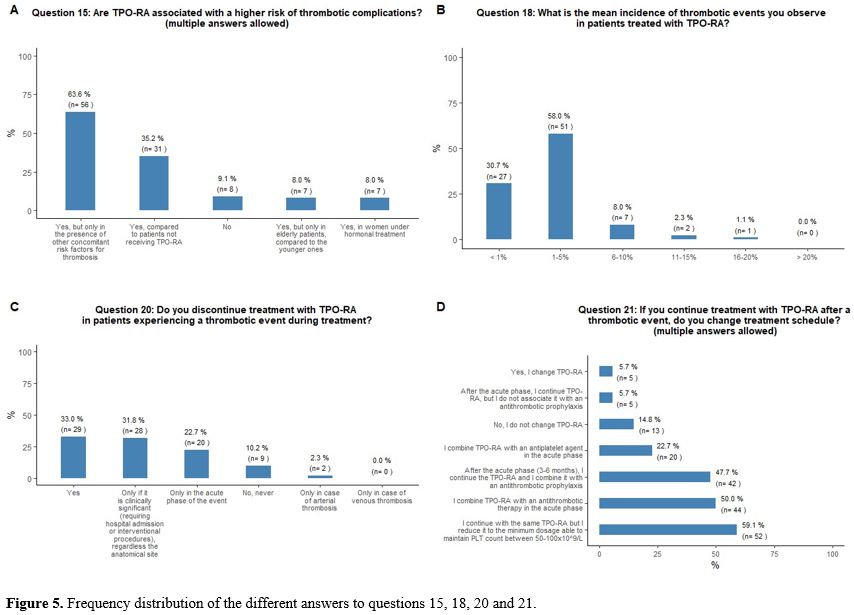

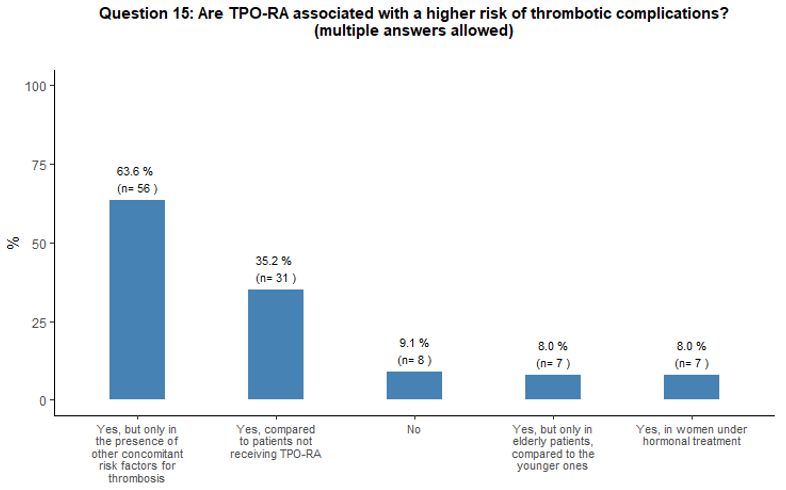

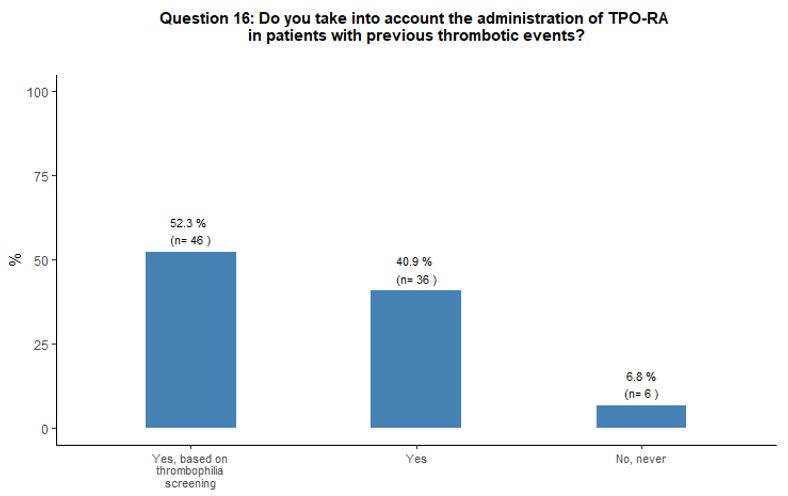

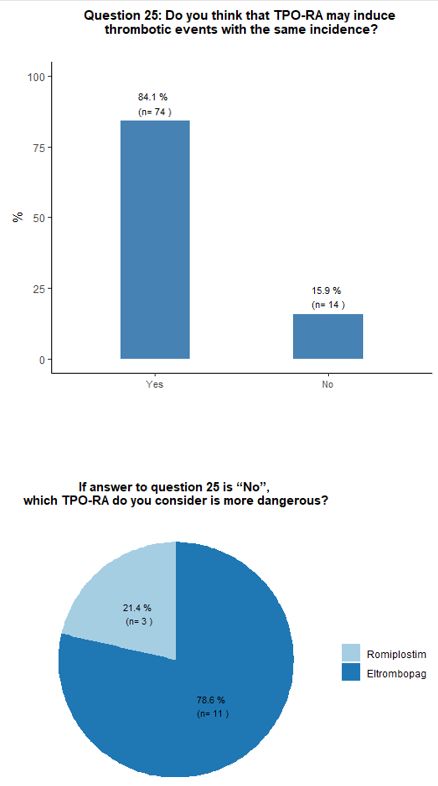

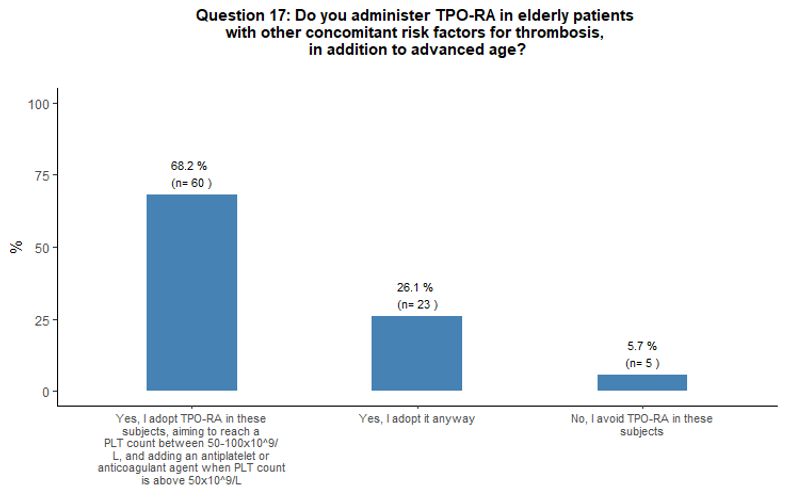

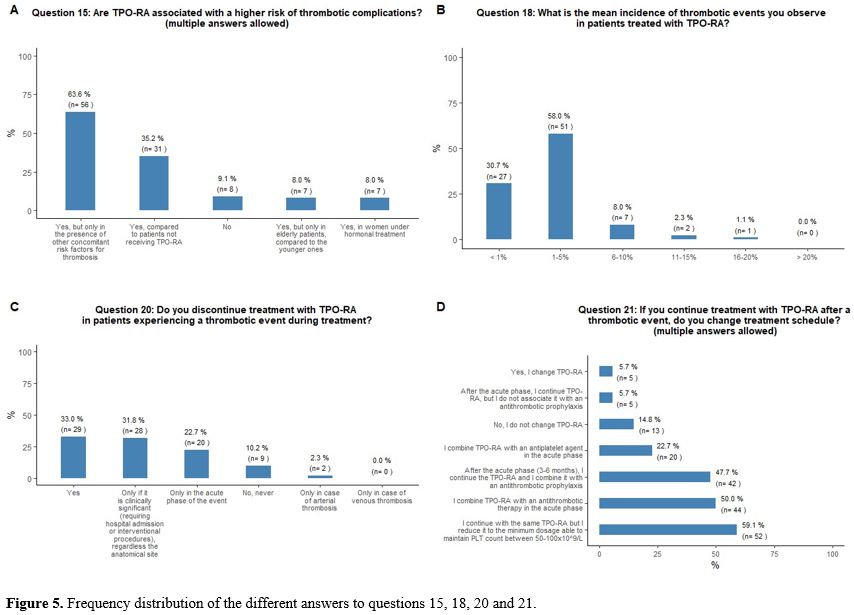

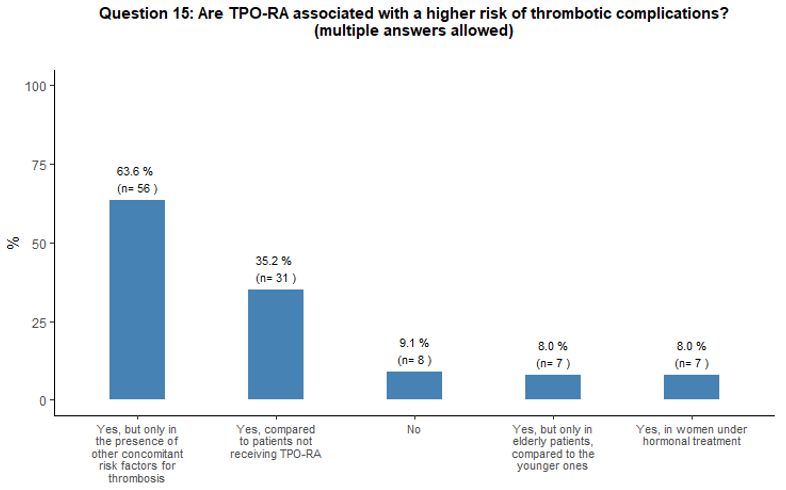

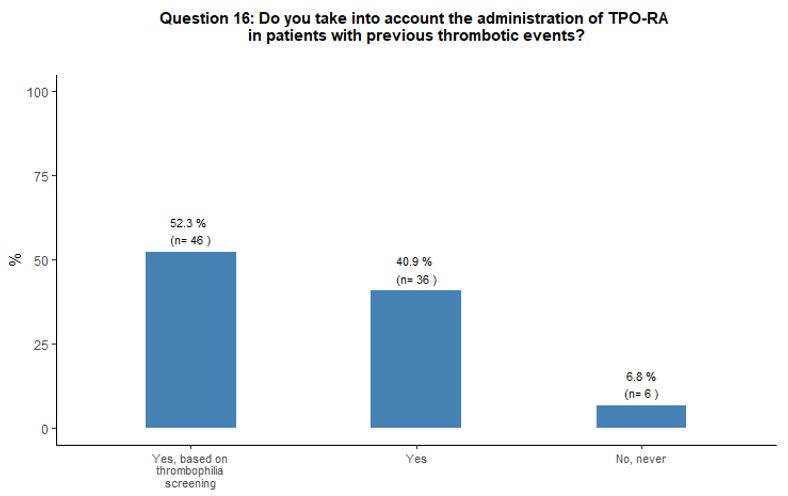

Perceived thrombotic risk associated with TPO-RA.

This section explored the participants' concern about a possible

increased thrombotic risk associated with TPO-RA and the treatment

preferences for patients with a recent history of thrombosis or

experiencing thrombosis while on TPO-RA.

Approximately 35% of

participants reported that, in their opinion, the administration of

TPO-RA could represent a thrombotic risk factor for patients. In

comparison, 64% of them consider that TPO-RA are associated with a

higher risk of thrombotic complications only in the presence of other

concomitant risk factors for thrombosis (Figure 5A).

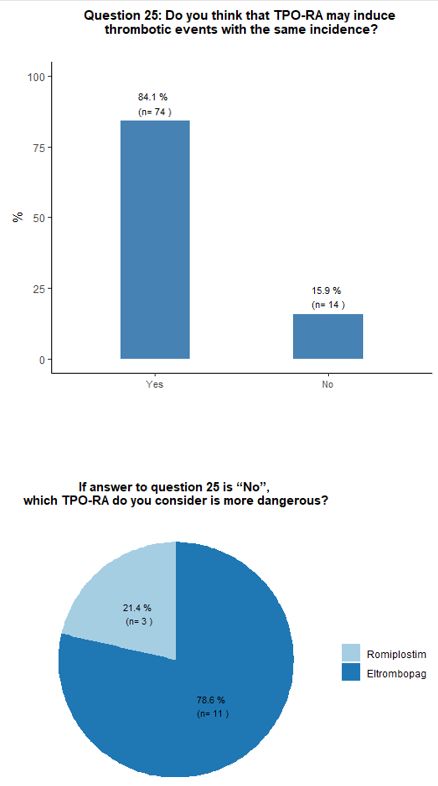

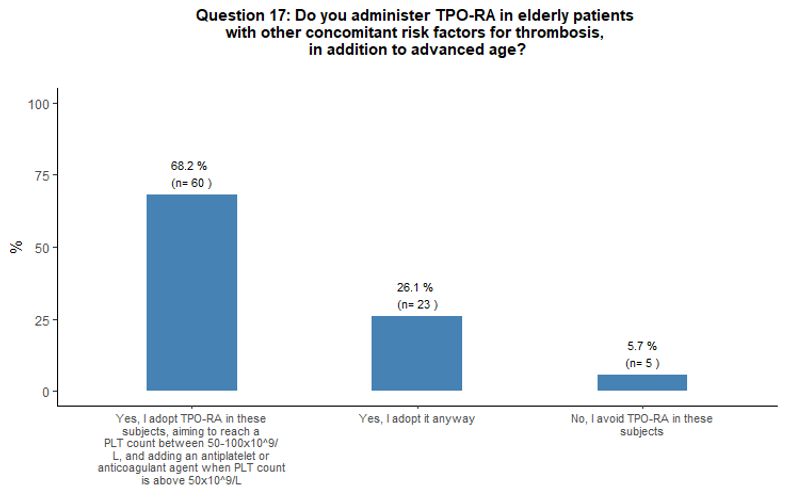

Almost all participants consider the possibility of prescribing TPO-RA

also in patients with a history of thrombosis. Half of them report the

need to evaluate coexisting additional clinical and laboratory

thrombosis risk factors accurately. Most participants (84%) believe

that romiplostim and eltrombopag have a similar potential to induce

thrombotic complications. A minority of respondents (13%) attribute a

higher thrombotic risk to eltrombopag. The vast majority (94%) of

respondents consider the administration of TPO-RA in elderly patients

to be overall sufficiently safe even in the presence of other

concomitant thrombotic risk factors (in addition to advanced age);

however, 68% of them consider appropriate to start primary

antithrombotic prophylaxis as soon as a platelet count at least above

50x109/L is obtained, aiming to reach a platelet count between 50-100x109/L. See questions 16, 25, and 17 in Appendix 1.

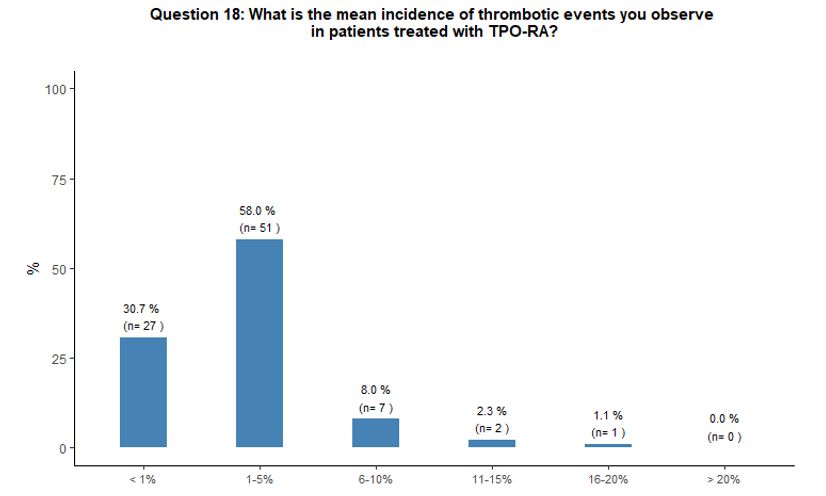

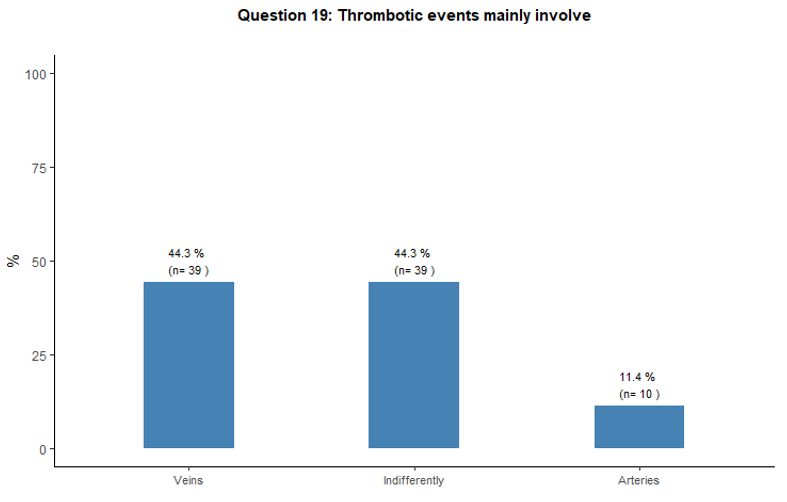

Perceived incidence of thrombosis during TPO-RA treatment and its management.

This section investigated the participants' perception of the risk of

early or late thrombotic events during treatment with TPO-RA and the

treatment approach that would have been used in case of thrombosis

during treatment.

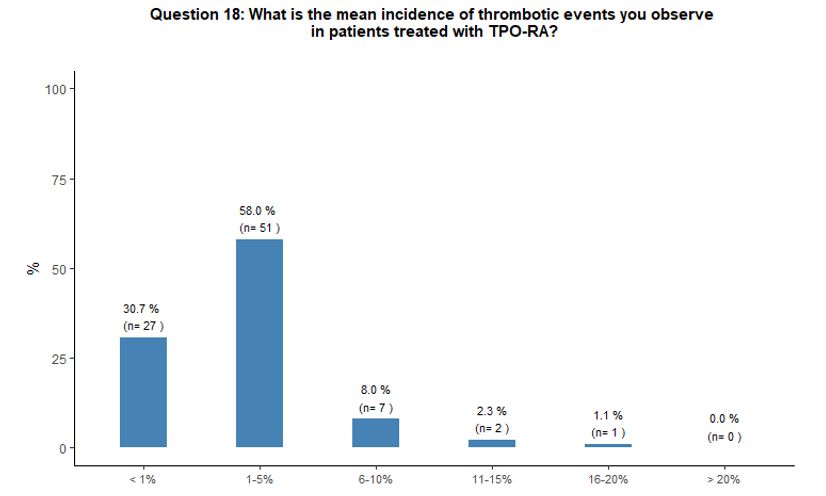

Sixty-six percent of participants report that

they have observed, in their common clinical practice, an incidence

rate of 1-10% of thrombotic complications during treatment with TPO-RA;

on the contrary, 31% reported thrombosis as a quite rare (with an

incidence rate < 1%) complication in patients treated with TPO-RA (Figure 5B).

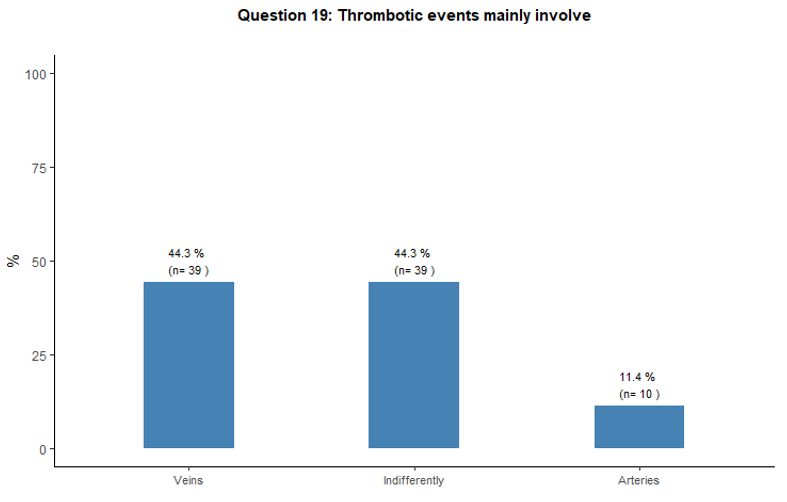

Thrombosis involved the venous and arterial vascular districts

indifferently according to 44% of the respondents; on the other hand,

44% and 12% of participants stated that thrombosis mainly involved

veins and arteries respectively. See question 19 in Appendix 1.

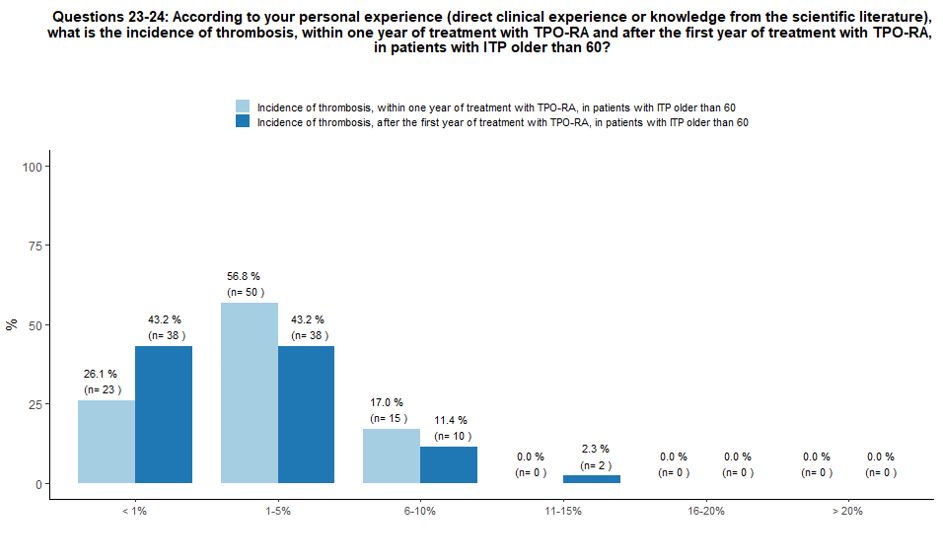

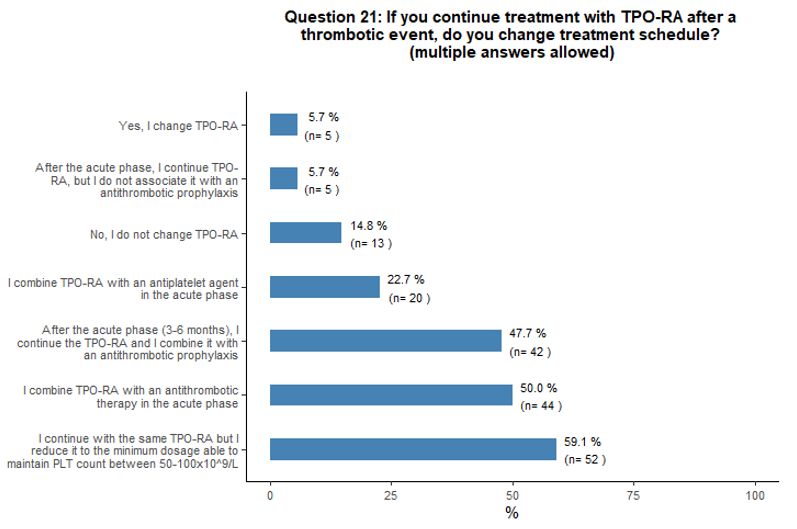

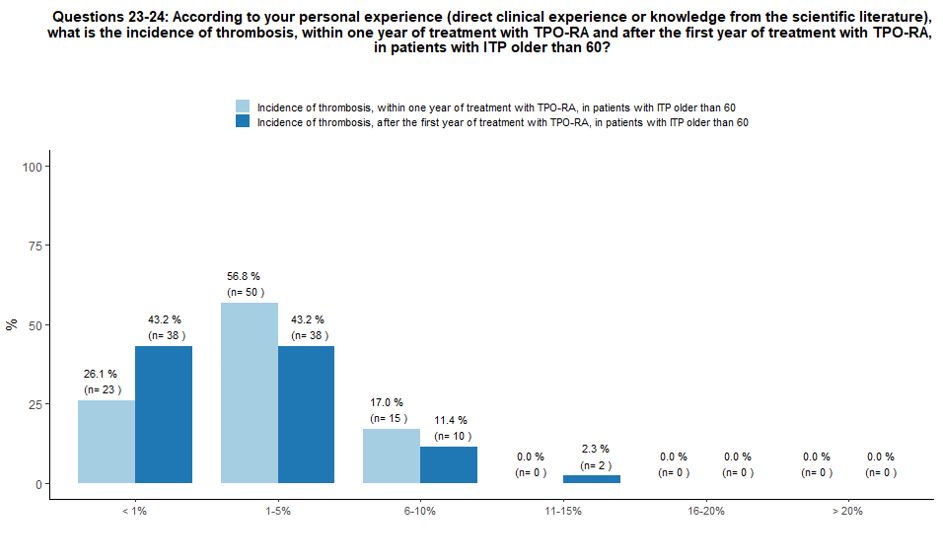

About

57% of participants, according to their personal experience and

knowledge of the literature, believe that the incidence of thrombotic

complications within one year after starting TPO-RA treatment in ITP

patients older than 60 years of age can be estimated at 1-5%, while 26%

and 17% of participants stated that the incidence of thrombosis in

these patients is <1% and 6-10% respectively. In the same context,

the incidence of thrombotic complications beyond the first year of

therapy with TPO-RA was considered <1% (43% of respondents), 1-5%

(43%); 6-10% (12%) and 11-15% (2%). See questions 23 and 24 in Appendix 1.

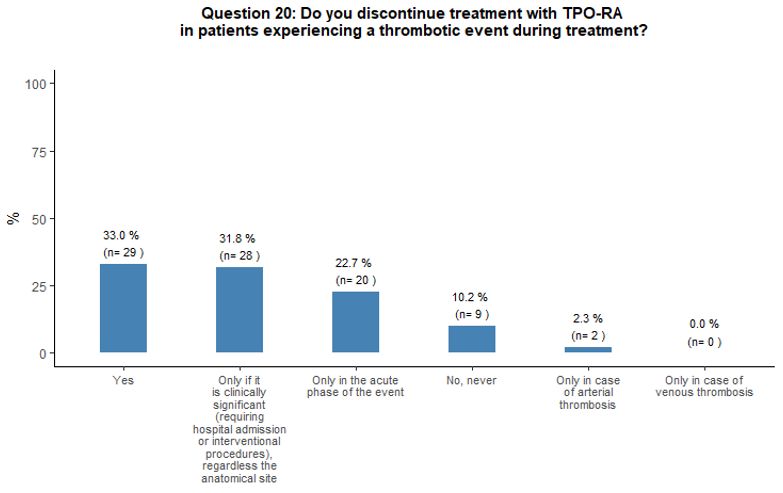

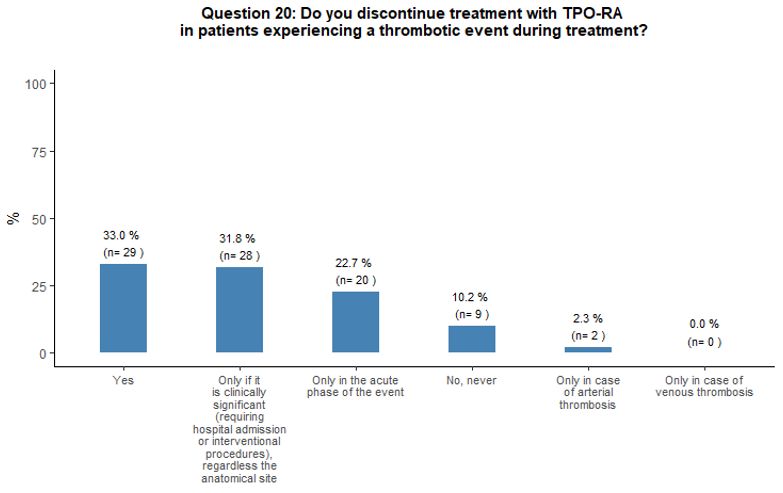

Thirty-three

percent of participants would withdraw TPO-RA in case of thrombosis,

32% would discontinue TPO-RA only if thrombosis is deemed as

"clinically relevant", 23% would withdraw them temporarily in the acute

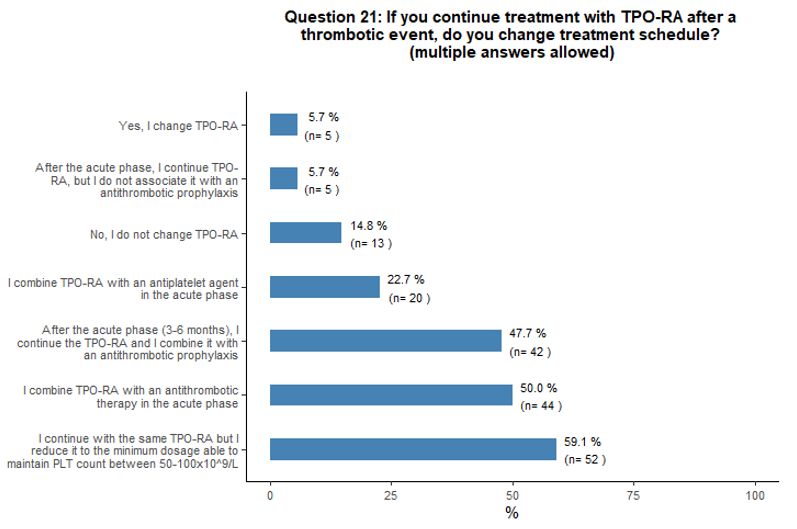

phase of the event, and 10% would continue the treatment. Fifty-nine

percent of participants that would continue TPO-RA treatment despite a

thrombotic event would continue with the same agent and reduce it to

the minimum dosage able to maintain platelet count between 50x109/L and 100x109/L.

Most participants would associate an antiplatelet or anticoagulant

agent in the absence of contraindication. Moreover, some participants

agreed that, in case of thrombotic complications, a multidisciplinary

approach is desirable to define the most appropriate antiplatelet and

anticoagulant agent (Figures 5C and 5D).

|

- Figure 5. Frequency distribution of the different answers to questions 15, 18, 20 and 21.

|

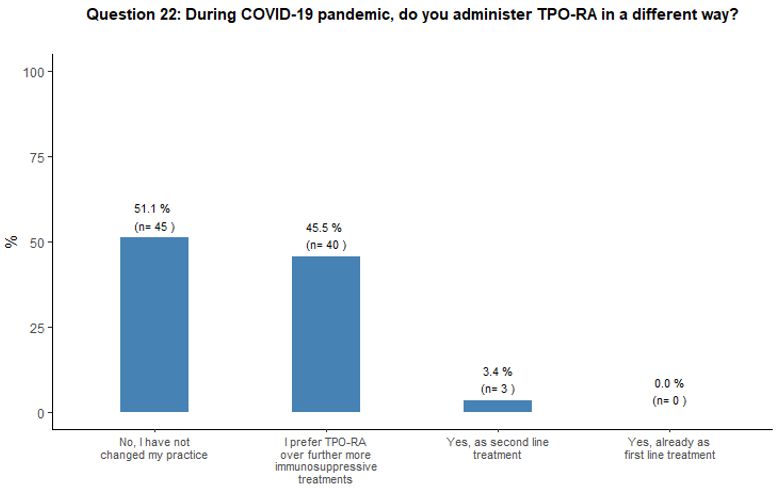

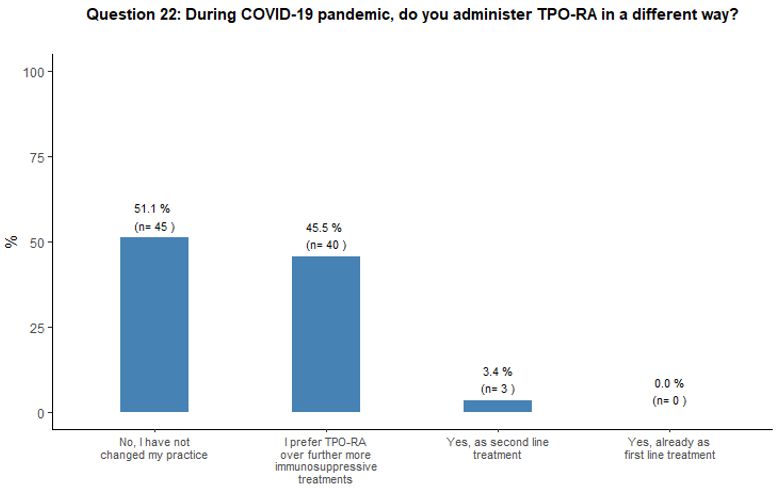

TPO-RA during COVID-19 pandemic.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on TPO-RA use was also explored.

Fifty-one percent of participants would not introduce any change in

their current practice on TPO-RA administration, while 46% of them

would prefer TPO-RA over a further, more immunosuppressive treatment,

and 3% would use TPO-RA as second-line treatment. See question 22 in Appendix 1.

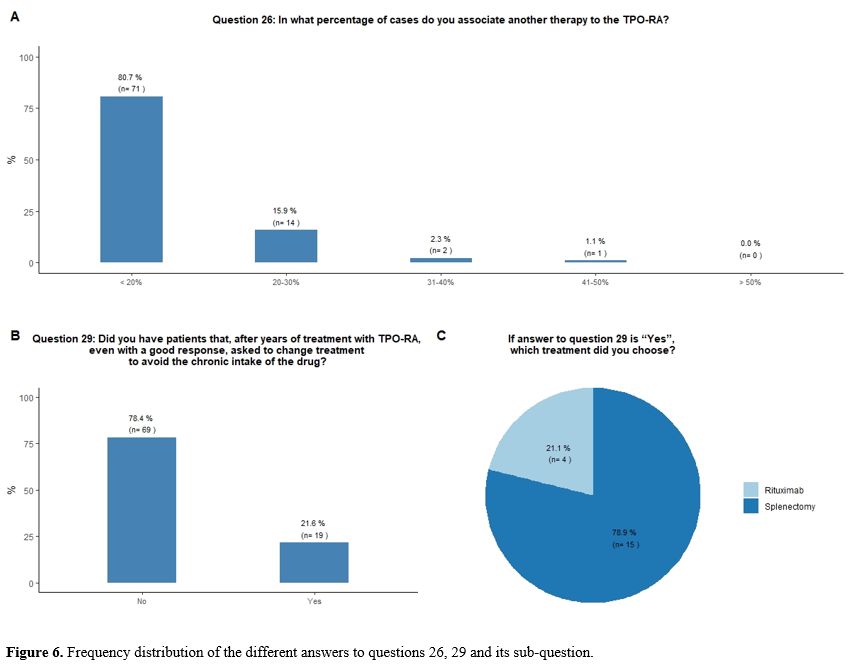

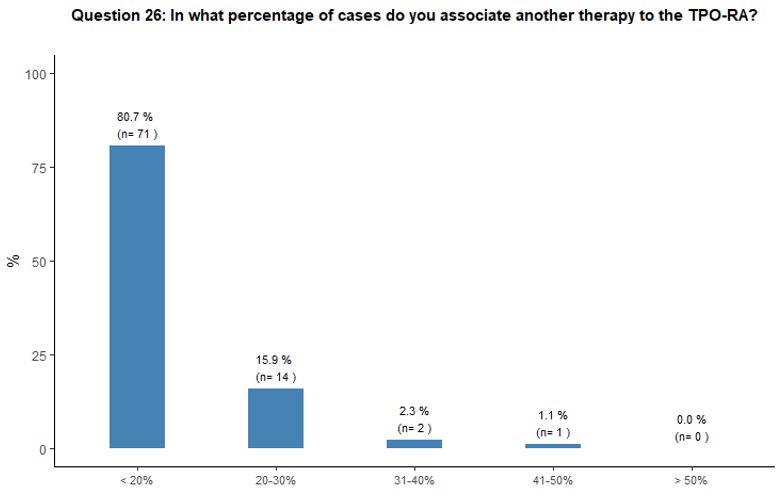

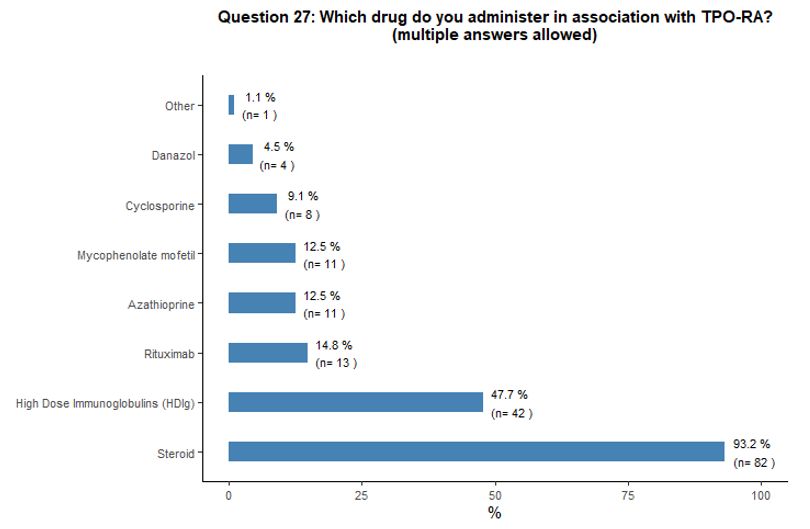

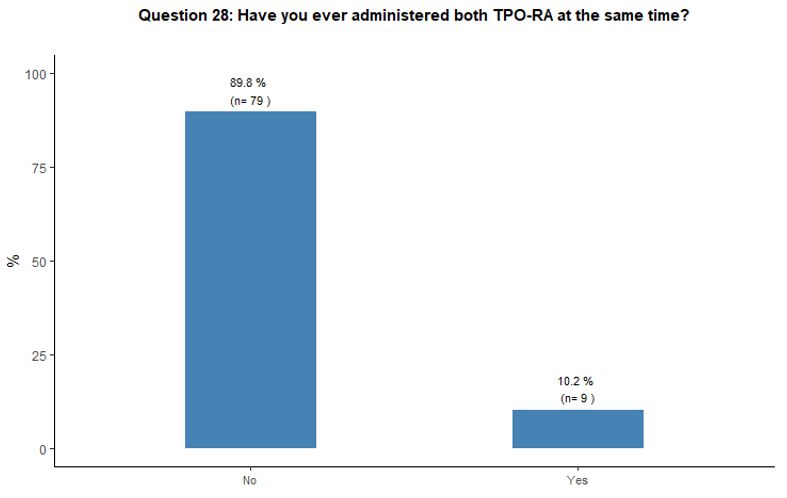

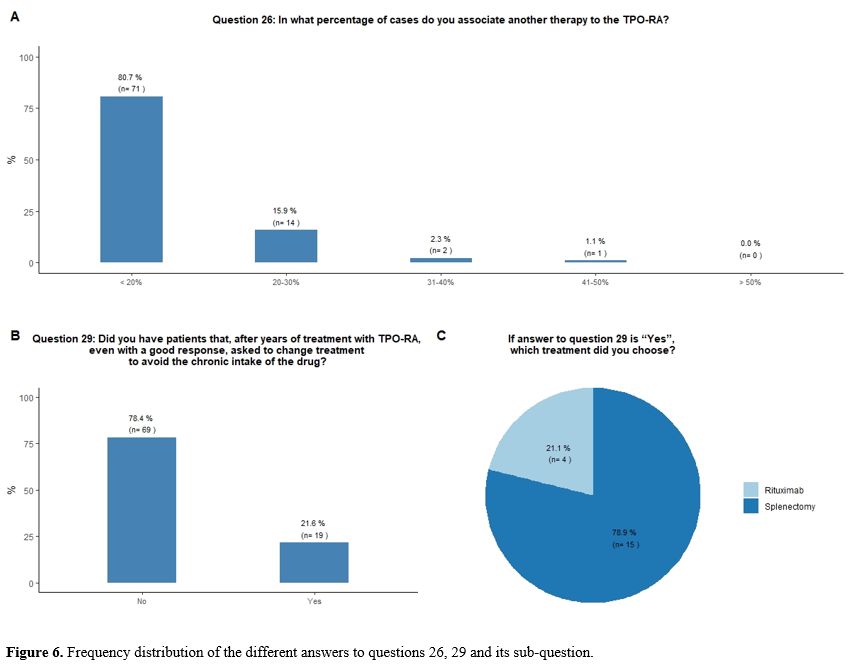

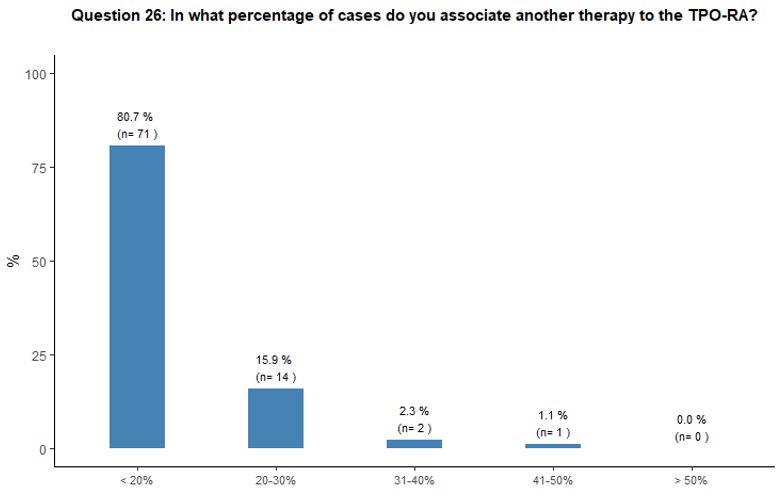

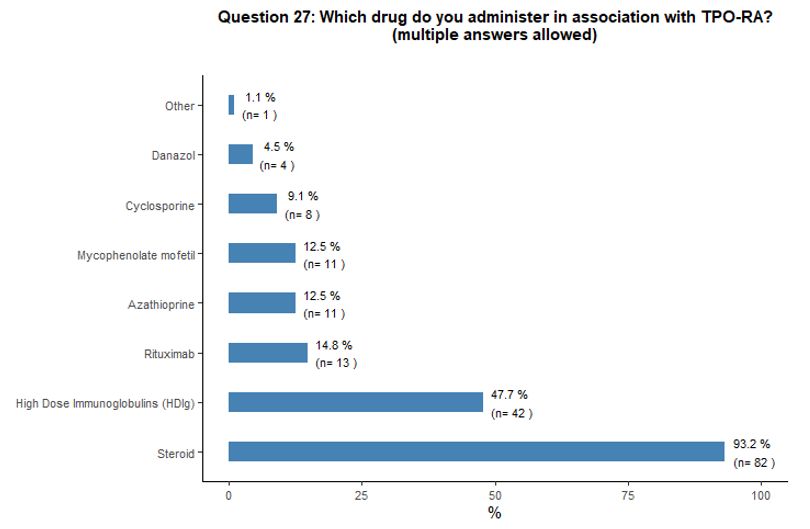

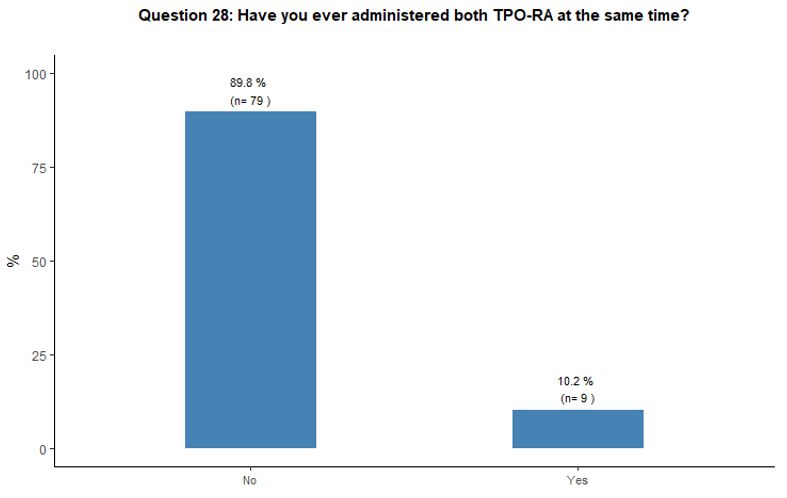

Administration of TPO-RA in combination or associated with other agents. Eighty-one percent of participants reported that they would associate another therapy to the TPO-RA in <20% of cases (Figure 6A).

Preference for specific medications associated with TPO-RA was rarely

indicated. Steroids and high-dose immunoglobulins (HDIg) are the most

frequently proposed drugs in association with TPO-RA, followed by a far

lower preference for azathioprine and cyclosporine. Ten percent of

participants reported that they would occasionally combine the two

available TPO-RA for selected refractory patients at a very high

bleeding risk but with poor results expected, based on their

experience. See questions 27 and 28 in Appendix 1.

Selected challenging scenarios.

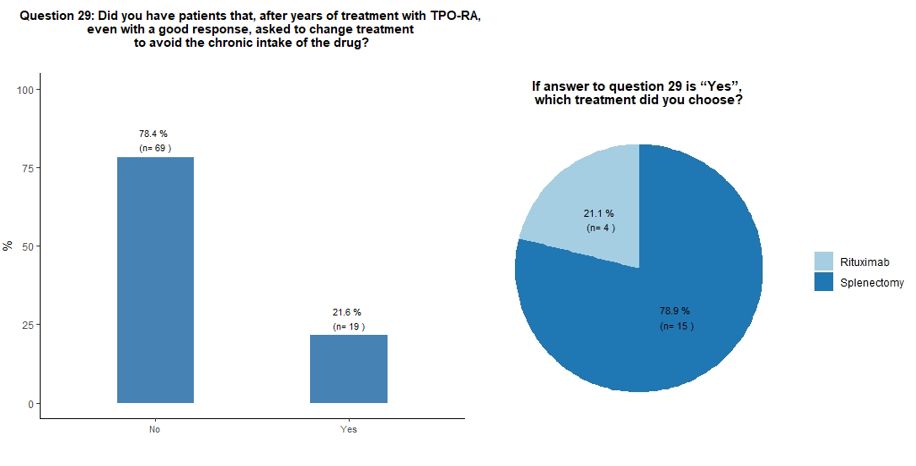

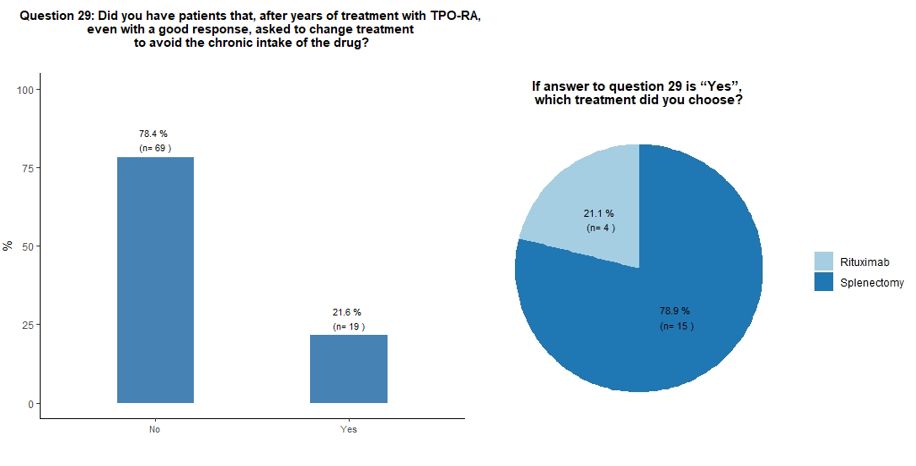

Seventy-eight percent of participants would indefinitely continue

treatment with TPO-RA in their responding patients, while 22% reported

that they received a request from the patient to change treatment to

avoid the chronic intake of the drug, despite a good response. In this

circumstance, participants would mostly suggest splenectomy, sometimes

already proposed by their patients, in the hope of obtaining a

treatment-free and long-term response (Figures 6B and 6C).

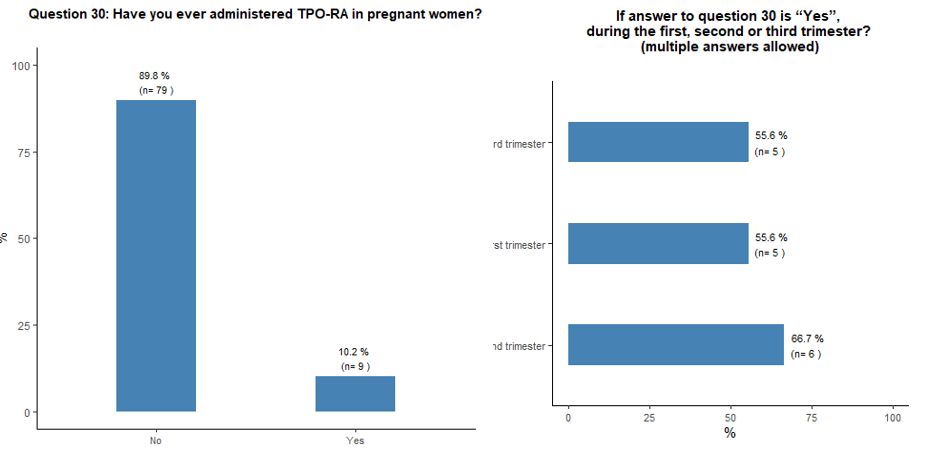

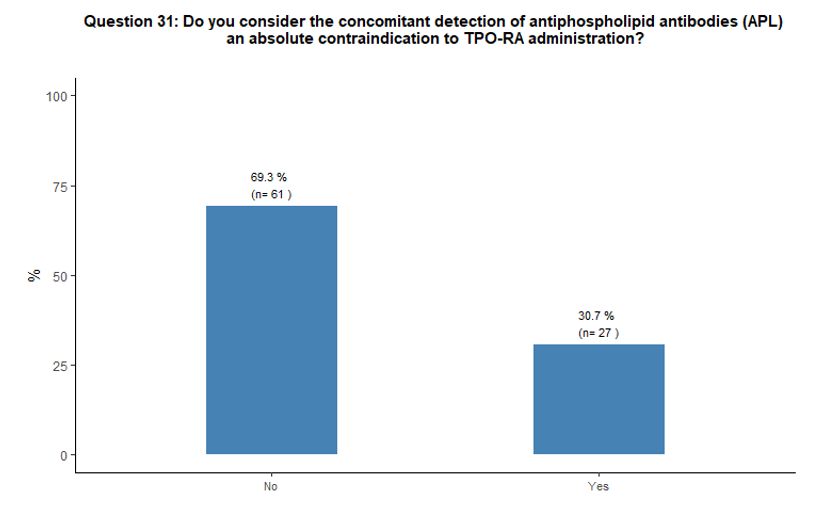

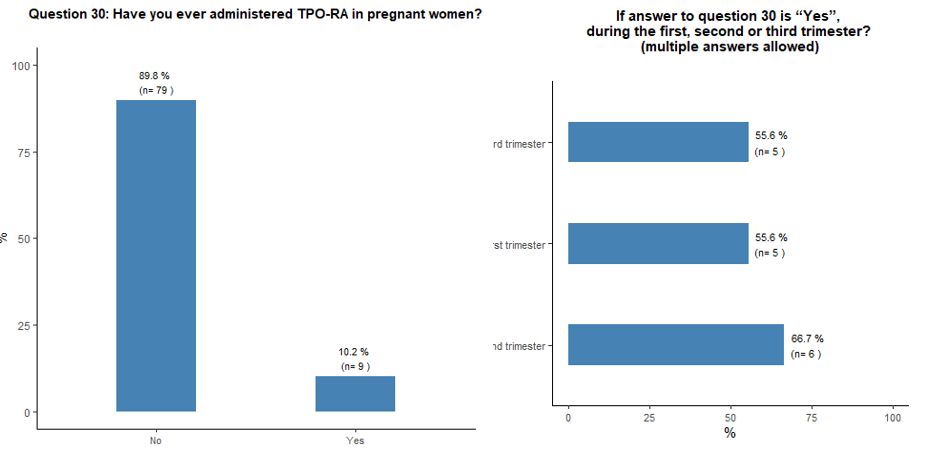

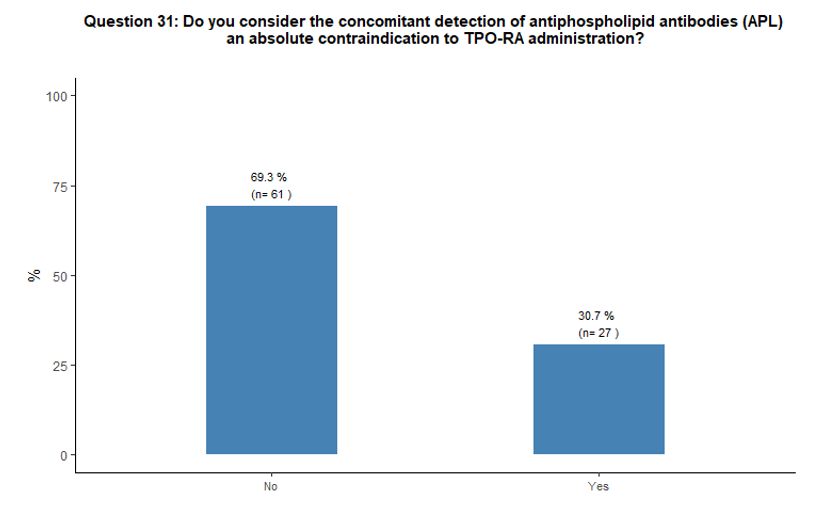

Ten

percent of participants reported using TPO-RA during pregnancy,

regardless of its phase. Sixty-nine percent do not consider the

presence of antiphospholipid antibodies as an absolute contraindication

to the use of TPO-RA, while 31% do so. See questions 30 and 31 in Appendix 1.

However, some participants suggest that it would be useful to have

guidelines providing indications for managing patients at high risk of

thrombosis.

|

- Figure 6. Frequency distribution of the different answers to questions 26, 29 and its sub-question.

|

Discussion

The

availability of TPO-RA in the treatment of ITP has significantly

modified the therapeutic approach to this disease in the last ten

years.[3-5] In 2014 the FDA decided to expand the

indications for TPO-RA use in the light of the availability of further

data concerning their efficacy and safety, allowing their

administration even in the persistent phase of the disease by removing

the limitation of refractoriness to splenectomy and, more recently,

allowing their use in children. For adults, at the time of this survey,

romiplostim was indicated after failure to first-line treatments[24] and eltrombopag after a minimum of 6 months.[25]

Recently,

several authors described the efficacy and safety of romiplostim and

eltrombopag immediately after an insufficient response to

corticosteroids in the real-world context. The early use of TPO-RA aims

to avoid inappropriate prolonged exposure to steroids with potentially

severe side effects while reducing the risk of severe bleeding. There

is also the emerging perspective that TPO-RA could modify the long-term

outcome of ITP by allowing to reach a TFR in a sizable proportion of

patients.[26-31]

TPO-RA are thus increasingly

evaluated in clinical practice for use in different contexts with

different modalities, not explored in the pivotal registration trials

which enrolled patients unresponsive to several lines of therapy,

including a significant proportion of those refractory to splenectomy.[32,33] In particular, TPO-RA were successfully used in elderly patients and as a bridge therapy to splenectomy.[34,35]

Gonzalez-Lopez et al.[36]

performed a retrospective analysis on eltrombopag administration in

adult patients affected by ITP, including 30 patients affected by newly

diagnosed ITP, 30 patients with persistent ITP and 160 subjects with

chronic ITP Results did not show any statistically significant

difference in terms of efficacy and safety among the 3 groups; however,

a trend towards a higher efficacy in newly diagnosed ITP was reported

(93.3% of responses with 86.7% of CR).

Lozano et al.[37]

revised available data on the early use of romiplostim reported in 9

clinical trials, 6 real-world studies and 10 case reports. Results of

this integrated analysis showed that romiplostim was as effective in

newly diagnosed/persistent ITP as in chronic ITP Therefore, the authors

suggested that an early administration of romiplostim may reduce

exposure duration to steroids.

Importantly, in recent years the

possibility of obtaining sustained response off therapy in

approximately 20-30% of responders has been reported in a phase 2 trial

with romiplostim[26] and in several clinical series with both romiplostim and eltrombopag.[27-31]

Tapering TPO-RA in search of a sustained response is part of current

practice, even in the absence of standardized criteria to guide patient

selection and tapering modalities.

Moreover, an effective

cross-over use of romiplostim and eltrombopag was demonstrated in case

of refractoriness or intolerance of one of the two.[38]

More

recently, TPO-RA are becoming a valuable, well-tolerated treatment

option for chronic and persistent ITP in children aged 1 year or older.

In addition, TPO-RA are also attractive for the management of ITP

during pregnancy in case of severe thrombocytopenia and lack of

response or side effects to standard approach with low/intermediate

doses of corticosteroids and/or IVIg.[39,40]

The

publication of the several studies mentioned above, and many other

similar reports worldwide, may have modified the clinicians' attitude

toward TPO-RA. As for Italy, it is worth noting that some authors of

the present paper contributed as co-authors in recent publications on

the evolving use of TPO-RA in clinical practice.[16,17,20,41,42]

Hence,

it is not surprising that the current survey has revealed that most

Italian hematologists consider desirable an earlier and much more

flexible administration of TPO-RA. Furthermore, most participants in

the current survey did not consider age as a limiting factor in the use

of this category of drugs, favorably taking into account the

possibility of administering TPO-RA also in elderly and very elderly

patients.

In about 30% of the interviewees, the risk of

thrombosis secondary to using TPO-RA was perceived as quite inferior to

what was reported in the available literature.[15] In

any case, it was not considered a limit to TPO-RA prescription.

However, it should be taken into account that thrombotic events

represent a not negligible complication of the use of TPO-RA, reported

to be 2-3 times higher than in untreated ITP patients, with an annual

incidence of 4.1% and 2.5%, observed for romiplostim and eltrombopag,

respectively.[9,15,43,44,45]

Some uncertainty continues, as to the increased risk of thrombosis

during TPO-RA administration. For example, a very recent meta-analysis

concerning the risk of thrombosis during treatment with TPO-RA compared

to placebo or standard of care shows that the number of thrombotic

events, even if higher in the TPO-RA group than in the control group,

does not translate into a statistically significant increment.[46]

Moreover, in elderly and young ITP patients treated with TPO-RA, the

annual incidence of thrombosis in a real-life context has recently been

substantially similar.[41] However, further studies are required to dismiss the increased thrombotic risk caused by TPO-RA, definitely.

Italian

hematologists consider important to administer primary antithrombotic

prophylaxis in patients at high thrombotic risk. On the other hand,

they would prefer, in most cases, to continue treatment with TPO-RA,

even after thrombosis, if a safe platelet count will allow secondary

prophylaxis. In the case of thrombotic complications, a

multidisciplinary approach with cardiologists and vascular medicine

specialists emerged as a common clinical practice to define better the

optimal anticoagulant and/or antiplatelet treatment.

Finally, the

COVID-19 pandemic has led experts to use more and more TPO-RA instead

of other treatments with immunosuppressive properties, aiming to reduce

the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection while ensuring therapeutic efficacy in

keeping with current National and International guidelines.[18,47]

In

this survey, some results, albeit obtained through a different

methodology, were quite similar to those that emerged from some expert

consensus reached by the Delphi method recently published[16,19,48]

on the topic of TPO-RA treatment tapering and discontinuation. However,

from all these data, there was not univocal and reliable guidance on

this important issue, yet, and further studies on this specific topic

were necessary. Moreover, specific issues afforded in the current

survey, concerning, for example, the use of TPO-RA in patients of

different ages, in context with a high risk of thrombosis or after a

thrombotic event and during SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, have not been

evaluated yet, thus leaving several questions still unanswered.

In

conclusion, the current survey shows that most Italian hematologists

assign a crucial role to TPO-RA, notwithstanding the many options for

managing ITP In particular, a more flexible and extensive use of TPO-RA

is suggested both in subjects who are refractory or poorly responsive

to steroids and in other specific categories of patients, such as the

elderly ones. However, the heterogeneous distribution of some answers

to the proposed questionnaire confirms the need for more accurate

information on several aspects concerning TPO-RA administration,

including: the timing and the modality of TPO-RA tapering in responsive

patients, the best management of relapsed patients after TPO-RA

discontinuation and the optimal treatment approach to patients with

concomitant cardiovascular risk factors or thromboembolic complications.

The

current treatment scenario has been recently expanded by the approval

of new drugs, either acting as TPO-RA (avatrombopag) or inhibitors of

spleen tyrosine kinase (fostamatinib). Moreover, several other drugs

are being currently evaluated in phase II-III studies exploring new

mechanisms of action such as, to name the principal ones, FcRn

(Fragment C Receptor Neonatal) inhibitors like efgartigimod;

rilzabrutinib, a reversible inhibitor of Bruton Tyrosine Kinase;

mezagitamab, an inhibitor of CD-38; and sutimlimab an inhibitor of C1s

in the classical complement pathway.[49] Hence, in

the next future, the present depicted real-world overview of the

Italian management of ITP will change in relation to the new available

drugs.

We trust that further real-life studies are needed to offer

a substantial answer to the perceived critical clinical issues as those

that emerged in this survey. These studies will also be useful in

informing on old, recent, and upcoming drugs and help to better

personalize ITP therapy by indicating each treatment's peculiar

benefits and limitations in the common practice.

Acknowledgements

We

thank the Hematology Project Foundation (HPF, Vicenza, Italy) for

funding the administrative costs of the project and the work of one of

its researchers (LG) and the Italian Group for Hematologic Malignancies

in Adults (GIMEMA Foundation, Rome, Italy) for providing the list and

addresses of the Italian Hematology Centers registered in its extensive

network.

References

- Stasi R. Immune thrombocytopenia: pathophysiologic and clinical

update. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2012;38:454-62.

https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0032-1305780 PMid:22753097

- Rodeghiero F,

Stasi R, Gernsheimer T, Michel M, Provan D, Arnold DM, Bussel JB, Cines

DB, Chong BH, Cooper N, Godeau B, Lechner K, Mazzucconi MG, McMillan R,

Sanz MA, Imbach P, Blanchette V, Kühne T, Ruggeri M, George JN.

Standardization of terminology, definitions and outcome criteria in

immune thrombocytopenic purpura of adults and children: report from an

international working group. Blood. 2009;113:2386-93.

https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2008-07-162503 PMid:19005182

- Lambert

MP, Gernsheimer TB. Clinical updates in adult immune thrombocytopenia.

Blood. 2017;129:2829-35. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2017-03-754119

PMid:28416506 PMCid:PMC5813736

- Provan D, Arnold DM, Bussel JB,

Chong BH, Cooper N, Gernsheimer T, Ghanima W, Godeau B, González-López

TJJ, Grainger J, Hou M, Kruse C, McDonald V, Michel M, Newland AC,

Pavord S, Rodeghiero F, Scully M, Tomiyama Y, Wong RS, Zaja F, Kuter

DJ. Updated international consensus report on the investigation and

management of primary immune thrombocytopenia. Blood Adv.

2019;3:3780-3817. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000812

PMid:31770441 PMCid:PMC6880896

- Neunert C, Terrell DR, Arnold DM,

Buchanan G, Cines DB, Cooper N, Cuker A, Despotovic JM, George JN,

Grace RF, Kühne T, Kuter DJ, Lim W, McCrae KR, Pruitt B, Shimanek H,

Vesely SK. American Society of Hematology 2019 guidelines for immune

thrombocytopenia. Blood Adv. 2019;3(23):3829-3866.

https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000966 PMid:31794604

PMCid:PMC6963252

- Al-Samkari H, Cronin A, Arnold DM, Rodeghiero F,

Grace RF. Extensive variability in platelet, bleeding, and QOL outcome

measures in adult and pediatric ITP: Communication from the ISTH SSC

subcommittee on platelet immunology. J Thromb Haemost.

2021;19(9):2348-2354. https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.15366

PMid:33974336

- Cooper N. State of the art - how I manage

immune thrombocytopenia. Brit J Haematol. 2017;177:39-54.

https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.14515 PMid:28295192

- Kubasch AS,

Kisro J, Heßling J, Schulz H, Hurtz H-J, Klausmann M, Ehrnsperger A,

Willy C, Platzbecker U. Disease management of patients with immune

thrombocytopenia-results of a representative retrospective survey in

Germany. Ann Hematol. 2020;99:2085-93.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-020-04173-5 PMid:32710167

PMCid:PMC7419449

- Ghanima W, Cooper N, Rodeghiero F, Godeau

B, Bussel JB. Thrombopoietin receptor agonists: ten years later.

Haematologica. 2019;104:1112-23.

https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2018.212845 PMid:31073079

PMCid:PMC6545830

- Vianelli N, Palandri F, Polverelli N, Stasi R,

Joelsson J, Johansson E, Ruggeri M, Zaja F, Cantoni S, Catucci AE,

Candoni A, Morra E, Björkholm M, Baccarani M, Rodeghiero F. Splenectomy

as a curative treatment for immune thrombocytopenia: a retrospective

analysis of 233 patients with a minimum follow up of 10 years.

Haematologica. 2013;98:875-80.

https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2012.075648 PMid:23144195

PMCid:PMC3669442

- Vibor M, Rogulj IM, Ostojic SK. Is there any Role

for Splenectomy in Adulthood Onset Chronic Immun e Thrombocytopenia in

the Era of TPO Receptors Agonists? A Critic al Overview. Cardiovasc

Hematological Disord Drug Targets. 2017;17:38-51. https://doi.org/10.2174/1871529X16666161229155608 PMid:28034281

- Thai

L-H, Mahévas M, Roudot-Thoraval F, Limal N, Languille L, Dumas G,

Khellaf M, Bierling P, Michel M, Godeau B. Long-term complications of

splenectomy in adult immune thrombocytopenia. Medicine. 2016;95:e5098.

https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000005098 PMid:27902585

PMCid:PMC5134764

- Rodeghiero F. A critical appraisal of the

evidence for the role of splenectomy in adults and children with ITP.

Brit J Haematol. 2018;181:183-95. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.15090

PMid:29479668

- Ghanima W, Godeau B, Cines DB, Bussel JB. How I

treat immune thrombocytopenia: the choice between splenectomy or a

medical therapy as a second-line treatment. Blood. 2012;120:960-69.

https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2011-12-309153 PMid:22740443

- Rodeghiero F. Is ITP a thrombophilic disorder? Am J Hematol. 2016;91:39-45. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.24234 PMid:26547507

- Carpenedo

M, Baldacci E, Baratè C, Borchiellini A, Buccisano F, Calvaruso G,

Chiurazzi F, Fattizzo B, Giuffrida G, Rossi E, Palandri F, Scalzulli

PR, Siragusa SM, Vitucci A, Zaja F. Second-line administration of

thrombopoietin receptor agonists in immune thrombocytopenia: Italian

Delphi-based consensus recommendations. Ther Adv Hematology.

2021;12:20406207211048360. https://doi.org/10.1177/20406207211048361

PMid:34646432 PMCid:PMC8504223

- Zaja F, Carpenedo M, Baratè C,

Borchiellini A, Chiurazzi F, Finazzi G, Lucchesi A, Palandri F, Ricco

A, Santoro C, Scalzulli PR. Tapering and discontinuation of

thrombopoietin receptor agonists in immune thrombocytopenia: Real-world

recommendations. Blood Rev. 2020;41:100647.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.blre.2019.100647 PMid:31818701

- Rodeghiero

F, Cantoni S, Carli G, Carpenedo M, Carrai V, Chiurazzi F, Stefano VD,

Santoro C, Siragusa S, Zaja F, Vianelli N. PRACTICAL RECOMMENDATIONS

FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF PATIENTS WITH ITP DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC :

Recommendation for ITP management during COVID. Mediterr J Hematology

Infect Dis. 2021;13:e2021032. https://doi.org/10.4084/MJHID.2021.032

PMid:34007420 PMCid:PMC8114883

- Cooper N, Hill QA, Grainger J,

Westwood J-P, Bradbury C, Provan D, Thachil J, Ramscar N, Roy A.

Tapering and Discontinuation of Thrombopoietin Receptor Agonist Therapy

in Patients with Immune Thrombocytopenia: Results from a Modified

Delphi Panel. Acta Haematol-basel. 2021;144:418-26.

https://doi.org/10.1159/000510676 PMid:33789275 PMCid:PMC8315674

- Cantoni

S, Carpenedo M, Mazzucconi MG, Stefano VD, Carrai V, Ruggeri M,

Specchia G, Vianelli N, Pane F, Consoli U, Artoni A, Zaja F, D'adda M,

Visentin A, Ferrara F, Barcellini W, Caramazza D, Baldacci E, Rossi E,

Ricco A, Ciminello A, Rodeghiero F, Nichelatti M, Cairoli R. Alternate

use of thrombopoietin receptor agonists in adult primary immune

thrombocytopenia patients: A retrospective collaborative survey from

Italian hematology centers. Am J Hematol. 2018;93:58-64.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.24935 PMid:28983953

- Harris PA, Taylor

R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data

capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process

for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed

Inform. 2009;42(2):377-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

PMid:18929686 PMCid:PMC2700030

- https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/nplate-epar-product-information_en.pdf

(Last updated 17/10/2022).

- https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/revolade-epar-product-information_en.pdf

(Last updated 04/11/22).

- https://farmaci.agenziafarmaco.gov.it/aifa/servlet/PdfDownloadServlet?pdfFileName=footer_002317_039002_RCP.pdf&sys=m0b1l3

- https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2020/08/28/20A04602/sg

- Newland

A, Godeau B, Priego V, Viallard J-FF, Fernández MFFL, Orejudos A, Eisen

M. Remission and platelet responses with romiplostim in primary immune

thrombocytopenia: final results from a phase 2 study. British Journal

of Haematology. 2016;172:262-73. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.13827

PMid:26537623

- González-López TJ, Pascual C, Álvarez-Román MT,

Fernández-Fuertes F, Sánchez-González B, Caparrós I, Jarque I,

Mingot-Castellano ME, Hernández-Rivas JA, Martín-Salces M, Solán L,

Beneit P, Jiménez R, Bernat S, Andrade MM, Cortés M, Cortti MJ,

Pérez-Crespo S, Gómez-Núñez M, Olivera PE, Pérez-Rus G, Martínez-Robles

V, Alonso R, Fernández-Rodríguez A, Arratibel MC, Perera M,

Fernández-Miñano C, Fuertes-Palacio MA, Vázquez-Paganini JA,

Gutierrez-Jomarrón I, Valcarce I, Cabo E de, Sainz A, Fisac R, Aguilar

C, Martínez-Badas MP, Peñarrubia MJ, Calbacho M, Cos C de,

González-Silva M, Coria E, Alonso A, Casaus A, Luaña A, Galán P,

Fernández-Canal C, Garcia-Frade J, González-Porras JR. Successful

discontinuation of eltrombopag after complete remission in patients

with primary immune thrombocytopenia. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:E40-43.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.23900 PMid:25400215

- Mahévas M,

Fain O, Ebbo M, Roudot‐Thoraval F, Limal N, Khellaf M, Schleinitz N,

Bierling P, Languille L, Godeau B, Michel M. The temporary use of

thrombopoietin‐receptor agonists may induce a prolonged remission in

adult chronic immune thrombocytopenia. Results of a French

observational study. Brit J Haematol. 2014;165:865-69.

https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.12888 PMid:24725224

- Lucchini E,

Palandri F, Volpetti S, Vianelli N, Auteri G, Rossi E, Patriarca A,

Carli G, Barcellini W, Celli M, Consoli U, Valeri F, Santoro C, Crea E,

Vignetti M, Paoloni F, Gigliotti CL, Boggio E, Dianzani U, Giardini I,

Carpenedo M, Rodeghiero F, Fanin R, Zaja F, (GIMEMA) for GIME

dell'Adulto. Eltrombopag second-line therapy in adult patients with

primary immune thrombocytopenia in an attempt to achieve sustained

remission off-treatment: results of a phase II, multicentre,

prospective study. Brit J Haematol. 2021;193:386-96.

https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.17334 PMid:33618438

- Iino M, Sakamoto

Y, Sato T. Treatment-free remission after thrombopoietin receptor

agonist discontinuation in patients with newly diagnosed immune

thrombocytopenia: an observational retrospective analysis in real-world

clinical practice. Int J Hematol. 2020;112(2):159-168.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12185-020-02893-y PMid:32476083

- Mazzucconi

MG, Santoro C, Baldacci E, Angelis FD, Chisini M, Ferrara G, Volpicelli

P, Foà R. TPO‐RAs in pITP: description of a case series and analysis of

predictive factors for response. Eur J Haematol. 2017;98:242-49.

https://doi.org/10.1111/ejh.12822 PMid:27797414

- Cheng G, Saleh MN,

Marcher C, Vasey S, Mayer B, Aivado M, Arning M, Stone NL, Bussel JB.

Eltrombopag for management of chronic immune thrombocytopenia (RAISE):

a 6-month, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet (London, England).

2011;377:393-402. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60959-2

- Kuter

DJ, Bussel JB, Lyons RM, Pullarkat V, Gernsheimer TB, Senecal FM,

Aledort LM, George JN, Kessler CM, Sanz MA, Liebman HA, Slovick FT,

Wolf J de, Bourgeois E, Guthrie TH, Newland A, Wasser JS, Hamburg SI,

Grande C, Lefrère F, Lichtin AE, Tarantino MD, Terebelo HR, Viallard

J-FF, Cuevas FJ, Go RS, Henry DH, Redner RL, Rice L, Schipperus MR, Guo

D, Nichol JL. Efficacy of romiplostim in patients with chronic immune

thrombocytopenic purpura: a double-blind randomised controlled trial.

Lancet (London, England). 2008;371:395-403.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60203-2

- Zaja F,

Barcellini W, Cantoni S, Carpenedo M, Caparrotti G, Carrai V, Renzo ND,

Santoro C, Nicola MD, Veneri D, Simonetti F, Liberati AM, Ferla V,

Paoloni F, Crea E, Volpetti S, Tuniz E, Fanin R. Thrombopoietin

receptor agonists for preparing adult patients with immune

thrombocytopenia to splenectomy: results of a retrospective,

observational GIMEMA study. American journal of hematology.

2016;91:E293-5. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.24341 PMid:26910388

- Lucchini

E, Fanin R, Cooper N, Zaja F. Management of immune thrombocytopenia in

elderly patients. European journal of internal medicine. 2018;58:70-76.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2018.09.005 PMid:30274902

- González-López

T, Fernández-Fuertes F, Hernández-Rivas J, Sánchez-González B,

Martínez-Robles V, Alvarez-Román M, Pérez-Rus G, Pascual C, Bernat S,

Arrieta-Cerdán E, Aguilar C, Bárez A, Peñarrubia M, Olivera P,

Fernández-Rodríguez A, Cabo E de, García-Frade L, González-Porras J.

Efficacy and safety of eltrombopag in persistent and newly diagnosed

ITP in clinical practice. International Journal of Hematology.

2017;106:508-16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12185-017-2275-4 PMid:28667351

- Lozano

ML, Godeau B, Grainger J, Matzdorff A, Rodeghiero F, Hippenmeyer J,

Kuter DJ. Romiplostim in adults with newly diagnosed or persistent

immune thrombocytopenia. Expert Rev Hematol. 2020;13:1-14.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17474086.2020.1850253 PMid:33249935

- Gómez-Almaguer

D. Eltrombopag-based combination treatment for immune thrombocytopenia.

Ther Adv Hematology. 2018;9:309-17.

https://doi.org/10.1177/2040620718798798 PMid:30344993 PMCid:PMC6187430

- Michel

M, Ruggeri M, Gonzalez-Lopez TJ, Alkindi S, Cheze S, Ghanima W, Tvedt

THA, Ebbo M, Terriou L, Bussel JB, Godeau B. Use of thrombopoietin

receptor agonists for immune thrombocytopenia in pregnancy: results

from a multicenter study. Blood. 2020;136:3056-61.

https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2020007594 PMid:32814348

- Bussel

JB, Cooper N, Lawrence T, Michel M, Haar EV, Wang K, Wang H, Saad H.

Romiplostim use in pregnant women with immune thrombocytopenia. Am J

Hematol. 2023;98:31-40. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.26743 PMid:36156812

- Palandri

F, Rossi E, Bartoletti D, Ferretti A, Ruggeri M, Lucchini E, Carrai V,

Barcellini W, Patriarca A, Rivolti E, Consoli U, Cantoni S, Oliva EN,

Chiurazzi F, Caocci G, Giuffrida G, Borchiellini A, Auteri G, Baldacci

E, Carli G, Nicolosi D, Sutto E, Carpenedo M, Cavo M, Mazzucconi MG,

Zaja F, Stefano VD, Rodeghiero F, Vianelli N. Real-world use of

thrombopoietin receptor agonists in older patients with primary immune

thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2021;138:571-83.

https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2021010735 PMid:33889952

- Mazza P,

Minoia C, Melpignano A, Polimeno G, Cascavilla N, Renzo ND, Specchia G.

The use of thrombopoietin-receptor agonists (TPO-RAs) in immune

thrombocytopenia (ITP): a "real life" retrospective multicenter

experience of the Rete Ematologica Pugliese (REP). Ann Hematol.

2016;95:239-44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-015-2556-z

PMid:26596973

- Kuter DJ, Bussel JB, Newland A, Baker RI,

Lyons RM, Wasser J, Viallard J, Macik G, Rummel M, Nie K, Jun S.

Long‐term treatment with romiplostim in patients with chronic immune

thrombocytopenia: safety and efficacy. Brit J Haematol.

2013;161:411-23. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.12260 PMid:23432528

- Bussel

JB, Saleh MN, Vasey SY, Mayer B, Arning M, Stone NL. Repeated

short‐term use of eltrombopag in patients with chronic immune

thrombocytopenia (ITP). Brit J Haematol. 2013;160:538-46.

https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.12169 PMid:23278590

- Saleh MN, Bussel

JB, Cheng G, Meyer O, Bailey CK, Arning M, Brainsky A, Group ES. Safety

and efficacy of eltrombopag for treatment of chronic immune

thrombocytopenia: results of the long-term, open-label EXTEND study.

Blood. 2013;121:537-45. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2012-04-425512

PMid:23169778

- Tjepkema M, Amini S, Schipperus M. Risk of

thrombosis with thrombopoietin receptor agonists for ITP patients: a

systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hemat.

2022;171:103581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2022.103581

PMid:35007700

- Pavord S, Thachil J, Hunt BJ, Murphy M, Lowe G,

Laffan M, Makris M, Newland AC, Provan D, Grainger JD, Hill QA.

Practical guidance for the management of adults with immune

thrombocytopenia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Brit J Haematol.

2020;189:1038-43. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.16775 PMid:32374026

PMCid:PMC7267627

- Cuker A, Despotovic JM, Grace RF, Kruse C,

Lambert MP, Liebman HA, Lyons RM, McCrae KR, Pullarkat V, Wasser JS,

Beenhouwer D, Gibbs SN, Yermilov I, Broder MS. Tapering thrombopoietin

receptor agonists in primary immune thrombocytopenia: Expert consensus

based on the RAND/UCLA modified Delphi panel method. Res Pract

Thrombosis Haemostasis. 2020;5:69-80.

https://doi.org/10.1002/rth2.12457 PMid:33537531 PMCid:PMC7845076

- Rodeghiero F. Recent progress in ITP treatment [published online ahead of print, 2023 Jan 9]. Int J Hematol.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12185-022-03527-1 PMid:36622549

Appendix

APPENDIX 1

to

“Nationwide survey on the use of thrombopoietin receptor agonists

(TPO-RA) for the management of immune thrombocytopenia in current

clinical practice in Italy”

SURVEY (ENGLISH TRANSLATION)

1)Based

on the available scientific literature, do you think that TPO-RA may be

adopted even at an earlier stage than allowed by the currently approved

indications?

o Yes

o No

o I don’t know

2)Where would you position TPO-RA treatment?

o As first line treatment, in association with steroids

o As first line treatment, as an alternative to steroids

o As first line treatment in selected cases (e.g. in diabetic or elderly or septic patients)

o Immediately after steroids failure, administered for the time indicated by guidelines

o

After steroids failure and second line treatment failure (anti CD20 or

splenectomy or other immunosuppressive drugs)

3)Which characteristics/factors may favour the administration of TPO-RA? (multiple answers allowed)

o Costs

o Home administration/delivery, drug availability

o Age

o Need of frequent contacts with the patient

o Time needed to reach a safe platelet count

o Easy dose definition

o Intolerance

o Platelet count fluctuations

o Comorbidities/concomitant medications/patient compliance

o Other

If answer to question 3 is “Other”, please specify which other characteristics/factors may favour TPO-RA administration.

4)Which characteristics/factors may disadvantage the administration of TPO-RA? (multiple answers allowed)

o Costs

o Home administration/delivery, drug availability

o Age

o Need of frequent contacts with the patient

o Time needed to reach a safe platelet count

o Easy dose definition

o Intolerance

o Platelet count fluctuations

o Comorbidities/concomitant medications/patient compliance

o Other

If answer to question 4 is “Other”, please specify which other characteristics may disadvantage TPO-RA administration.

5)Do you administer TPO-RA more frequently:

o In young patients

o In elderly patients

o Indifferently

6)If

you adopt different approaches in young and elderly patients, please

specify the main reasons that lead you to this choice: (multiple

answers allowed)

o Different thrombotic risk

o Different bleeding risk

o Toxicity

o Lifestyle (e.g. frequent travels)

o Nutrition

o Different patient expectations

o Higher frequency of concomitant disorders in the elderly patient

o Higher burden for the elderly patient in accessing the hospital for frequent visits

o I do not adopt different approaches in young and elderly patients

7)Do

you think that TPO-RA may be administered at different time points to

patients older than 65 years of age, compared to younger subjects?

o No

o

Yes, I adopt them as a second line therapy after cortisone, regardless

of the presence or not of cardiovascular risk factors or comorbidities

o

Yes, I adopt them as second line therapy, only in the absence of

comorbidities impacting the cardiovascular risk

8)What is your aim in prescribing TPO-RA to young patients?

o To reach a safe platelet count (above 30-50 x 109/L )

o To reach a complete response (in order to evaluate tapering/discontinuation at a later time)

o Other

If answer to question 8 is “Other”, please specify for what purpose you administer TPO-RA in young patients.

9)What is your aim in prescribing TPO-RA to elderly patients?

o To reach a safe platelet count (above 30-50 x 109/L)

o To reach a complete response (in order to evaluate tapering/discontinuation at a later time)

o Other

If answer to question 9 is “Other”, please specify for what purpose you administer TPO-RA in elderly patients.

10)When do you switch from one TPO-RA to another? (multiple answers allowed)

o When PLT count is less than 20-30 x 109/L or less than double the basal value, after the administration of the maximum allowed dose for four consecutive weeks

o When PLT count is less than 20-30 x 109/L

or less than double the basal value, even without waiting to have

reached the maximum allowed dose if the patient has bleeding diathesis

o When a stable PLT count cannot be obtained, due to wide fluctuations in PLT count

o In case of grade 3 toxicity

o When the patient loses the response to the first TPO-RA

o Patient preferences

o Other

If answer to question 10 is “Other”, please specify when to switch from one TPO-RA to another.

11)According

to your experience, in what percentage of cases is it possible to

maintain a haematological response, even after treatment

discontinuation (Treatment Free Response, TFR)?

o In no case

o In 5-10% of patients

o In 10-20% of patients

o In 20-30% of patients

o In 30-40% of patients

o In 40-50% of patients

12)When do you take into account the possibility to discontinue TPO-RA treatment, aiming to achieve TFR?

o When PLT≥100 x 109/L for at least 3 months

o When PLT≥100 x 109/L for at least 6 months

o When PLT≥100 x 109/L for at least 9 months

o When PLT≥100 x 109/L for at least 12 months

o When PLT≥50 x 109/L for at least 3 months

o When PLT≥50 x 109/L for at least 6 months

o When PLT≥50 x 109/L for at least 9 months

o When PLT≥50 x 109/L for at least 12 months

13)How do you manage TPO-RA discontinuation (tapering schedule)?

o

I adopt a pre-defined tapering method that I apply regularly for both

TPO-RA in all patients in which I try tapering

o

I do not adopt a pre-defined tapering method that I apply regularly for

both TPO-RA and I define the tapering schedule for each patient based

on the patient’s response

13A)How do you taper TPO-RA?

o

I only reduce the TPO-RA dosage, keeping standard intervals between

doses, as suggested by the drug technical sheet

o

I only prolong the interval between TPO-RA doses, keeping the effective

dose unchanged, up to complete treatment discontinuation

o I modify both the TPO-RA dosage and the intervals between administrations

13B) What is the tapering duration?

o Slow, progressive tapering, for a stable PLT count, until discontinuation within 4-6 months

o Slow, progressive tapering, for a stable PLT count, until discontinuation within 2-4 months

o Slow, progressive tapering, for a stable PLT count, until discontinuation within 1-2 months

o Other

If answer to question 13B is “Other”, please specify the timing of the tapering.

14)During TPO-RA tapering, if platelet count decrease < 50 x 109/L without bleeding diathesis:

o The effective dosage before tapering attempt is restored, and no further tapering is attempted

o

The dosage immediately preceding the last one is restored, even if

lower than the one before the start of tapering, and tapering is then

continued with prolonged time intervals

o Low doses of steroids are temporarily associated to TPO-RA and tapering is continued

15)Are TPO-RA associated with a higher risk of thrombotic complications? (multiple answers allowed)

o Yes, compared to patients not receiving TPO-RA

o Yes, but only in elderly patients compared to the younger ones

o Yes, in women under hormonal treatment

o Yes, but only in the presence of other concomitant risk factors for thrombosis

o No

16)Do you take into account the administration of TPO-RA in patients with previous thrombotic events?

o Yes

o Yes, based on thrombophilia screening

o No, never

17)Do you administer TPO-RA in elderly patients with other concomitant risk factors for thrombosis in addition to advanced age?

o No, I avoid TPO-RA in these subjects

o Yes, I adopt it anyway

o Yes, I adopt TPO-RA in these subjects, aiming to reach a PLT count between 50-100 x 109/L, and adding an antiplatelet or anticoagulant agent when PLT count is above 50 x 109/L

18)What is the mean incidence of thrombotic events you observe in patients treated with TPO-RA?

o <1%

o 1-5%

o 6-10%

o 11-15%

o 16-20%

o >20%

19)Thrombotic events mainly involve

o Arteries

o Veins

o Indifferently

20)Do you discontinue treatment with TPO-RA in patients experiencing a thrombotic event during treatment?

o Yes

o No, never

o Only in case of venous thrombosis

o Only in case of arterial thrombosis

o Only in the acute phase of the event

o

Only if it is clinically significant (requiring hospital admission or

interventional procedures), regardless the anatomical site

21)If you continue treatment with TPO-RA after a thrombotic event, do you change treatment schedule? (multiple answers allowed)

o Yes, I change TPO-RA

o No, I do not change TPO-RA

o

I continue with the same TPO-RA but I reduce it to the minimum dosage

able to maintain PLT count between 50-100 x 109/L

o I combine TPO-RA with an antithrombotic therapy in the acute phase

o I combine TPO-RA with an antiplatelet agent in the acute phase

o

After the acute phase (3-6 months), I continue the TPO-RA and I combine

it with an antithrombotic prophylaxis

o After the acute phase, I continue TPO-RA but I do not associate it with an antithrombotic prophylaxis

If answer to question 21 is “I combine TPO-RA with an antithrombotic therapy in the acute phase”, which antithrombotic treatment do you administer in the acute phase?

If answer to question 21 is “I combine TPO-RA with an antiplatelet agent in the acute phase”, which antiplatelet agent do you administer in the acute phase?

If

answer to question 21 is “After the acute phase (3-6 months), I

continue the TPO-RA and I combine it with an antithrombotic

prophylaxis”, which antithrombotic prophylaxis do you administer after the acute phase? How long?

22)During COVID-19 pandemic, do you administer TPO-RA in a different way?

o No, I have not changed my practice

o Yes, already as first line treatment

o Yes, as second line treatment

o I prefer TPO-RA over further more immunosuppressive treatments

23)According

to your personal experience (direct clinical experience or knowledge

from the scientific literature), what is the incidence of thrombosis,

within one year of treatment with TPO-RA, in patients with ITP older

than 60?

o <1%

o 1-5%

o 6-10%

o 11-15%

o 16-20%

o >20%

24)According

to your personal experience (direct clinical experience or knowledge

from the scientific literature), what is the incidence of thrombosis,

after the first year of treatment with TPO-RA, in patients with ITP

older than 60?

o <1%

o 1-5%

o 6-10%

o 11-15%

o 16-20%

o >20%

25)Do you think that TPO-RA may induce thrombotic events with the same incidence?

o Yes

o No

If answer to 25 is “No”, which TPO-RA do you consider is more dangerous?

o Eltrombopag

o Romiplostim

26)In what percentage of cases do you associate another therapy to the TPO-RA?

o <20%

o 20-30%

o 31-40%

o 41-50%

o >50%

27)Which drug do you administer in association with TPO-RA? (multiple answers allowed)

o Steroid

o High Dose Immunoglobulins (HDIg)

o Rituximab

o Mycophenolate mofetil

o Cyclosporine

o Azathioprine

o Danazol

o Other

If answer to question 27 is “Other”, specify the drug(s) you combine with TPO-RA.

28)Have you ever administered both TPO-RA at the same time?

o Yes

o No

If answer to question 28 is “Yes”, specify the reason.

If answer to question 28 is “Yes”, specify the response rate.

29)Did

you have patients that, after years of treatment with TPO-RA, even with

a good response, asked to change treatment to avoid the chronic intake

of the drug?

o Yes

o No

If answer to question 29 is “Yes”, which treatment did you choose?

o Rituximab

o Splenectomy

30)Have you ever administered TPO-RA in pregnant women?

o Yes

o No

If answer to question 30 is “Yes”, during the first, second or third trimester? (multiple answers allowed)

o First trimester

o Second trimester

o Third trimester

If answer to question 30 is “Yes”, in how many patients?

31)Do

you consider the concomitant detection of antiphospholipid antibodies

(APL) an absolute contraindication to TPO-RA administration?

o Yes

o No

If answer to question 31 is “No”, how many patients have you treated?

Comments

SUMMARY OF THE ANSWERS TO THE ITEMS DIVIDED IN THE 9 ADDRESSED DOMAINS

Timing of administration of TPO-RA and preferred agent

|

- Question 1

|

|

- Question 2

|

Modality and purpose of treatment in young and elderly patients

|

- Question 3-4

|

|

- Question 5

|

|

- Question 6

|

|

- Question 7

|

Parameters evaluated to discontinue treatment in young and elderly patients

|

- Question 8-9

|

|

- Question 11

|

|

- Question 12

|

Switching and tapering of TPO-RA

|

- Question 10

|

|

- Question 13

|

|

- Question 13A

|

|

- Question 13B

|

|

- Question 14

|

Perceived thrombotic risk associated with TPO-RA

|

- Question 15

|

|

- Question 16

|

|

- Question 25

|

|

- Question 17

|

Perceived incidence of thrombosis during TPO-RA treatment and its management

|

- Question 18

|

|

- Question 19

|

|

- Question 20

|

|

- Question 21

|

|

- Question 23-24

|

TPO-RA during COVID-19 pandemic

|

- Question 22

|

Administration of TPO-RA in combination or associated with other agents

|

- Question 26

|

|

- Question 27

|

|

- Question 28

|

|

- Question 29

|

|

- Question 30

|

|

- Question 31

|

APPENDIX 2

to

“Nationwide survey on the use of thrombopoietin receptor agonists

(TPO-RA) for the management of immune thrombocytopenia in current

clinical practice in Italy”

List of participants

[TOP]