Stefanie von Matt1, Ulrike Bacher2, Yara Banz3, Behrouz Mansouri Taleghani2, Urban Novak1 and Thomas Pabst1

1

Department of Medical Oncology; Inselspital, Bern University Hospital, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland.

2

Department of Hematology and Central Hematology Laboratory;

Inselspital, Bern University Hospital, University of Bern, Bern,

Switzerland.

3 Institute of Pathology, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland.

Correspondence to:

Prof. Thomas Pabst, MD; Department of Medical Oncology; University

Hospital; 3010 Bern; Switzerland. Tel.: +41 31 632 8430; Fax: +41 31

632 3410; E-mail:

thomas.pabst@insel.ch.

Published: May 1, 2023

Received: December 30, 2022

Accepted: April 16, 2023

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2023, 15(1): e2023025 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2023.025

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Introduction:

Autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) following high-dose

chemotherapy is applied as salvage therapy in patients with relapsed

disease or as first-line consolidation in high-risk DLBCL with

chemo-sensitive disease. However, the prognosis of relapsing DLBCL

post-ASCT remained poor until the availability of CAR-T cell treatment.

To appreciate this development, understanding the outcome of these

patients in the pre-CAR-T era is essential.

Methods: We retrospectively analyzed 125 consecutive DLBCL patients who underwent HDCT/ASCT.

Results:

After a median follow-up of 26 months, OS and PFS were 65% and 55%.

Fifty-three patients (42%) had a relapse (32 patients, 60%) or

refractory disease (21 patients, 40%) after a median of 3 months

post-ASCT. 81% of relapses occurred within the first year post-ASCT

with an OS of 19% versus 40% at the last follow-up in patients with

later relapses (p=0.0022). Patients with r/r disease after ASCT had

inferior OS compared to patients in ongoing remission (23% versus 96%;

p<0.0001). Patients relapsing post-ASCT without salvage therapy

(n=22) had worse OS than patients with 1-4 subsequent treatment lines

(n=31) (OS 0% versus 39%; median OS 3 versus 25 months; p<0.0001).

Forty-one (77%) of patients relapsing after ASCT died, 35 of which due

to progression.

Conclusions:

Additional therapies can extend OS but mostly cannot prevent death in

DLBCL relapsing/refractory post-ASCT. This study may serve as a

reference to emerging results after CAR-T treatment in this population.

|

Introduction

Diffuse

large B-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified (DLBCL, NOS) responds

effectively to immunochemotherapy, with R-CHOP (rituximab,

cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) being the

first-line standard.[1-6] In up to 60% of patients, this treatment provides definite complete remission.[7,8]

Nevertheless, 30-50% of patients will suffer from relapsed or

progressive disease, mostly within the first two years. The current

treatment of choice for this patient population is salvage chemotherapy

followed by high-dose chemotherapy (HDCT) with peripheral autologous

hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (ASCT).[9-12] The most widely used HDCT regimens are BEAM (carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan),[11,13] or BeEAM with bendamustine replacing BCNU.[14,15]

Although

HDCT followed by ASCT is a successful treatment option for many

patients with relapsed DLBCL or high-risk presentation, this treatment

is associated with relevant toxicity; importantly, up to 50% of these

patients will still relapse or are refractory to this treatment.[16-19]

Prognosis of these patients is dismal, and treatment options have been

limited so far. Some r/r patients may not receive further interventions

after HDCT/ASCT due to lack of response to salvage chemotherapy, poor

general condition, or the patient’s request, and they undergo

palliative treatment. For patients eligible for further therapies,

options comprise chemotherapy, immunotherapy, radiotherapy, or

combinations of these, in selected cases, allogeneic hematopoietic stem

cell transplantation, a second ASCT, or, more recently, CAR (chimeric

antigen receptor) T-cell therapy.[11,20]

CAR T-cell therapy is a promising new option for patients with DLBCL

after two or more therapy lines fail. Recent studies have shown

remarkable CR rates of between 40% to 58%.[21-26] On

the other hand, CAR T-cell therapy can be associated with relevant

specific complications, including cytokine release syndrome (CRS) or

CAR T-cell-related encephalopathy syndrome (CRES/ICANS).[21-25,27-29]

We performed a retrospective study to describe the outcome of patients

with DLBCL after HDCT/ASCT and to determine how high-risk or relapsed

DLBCL was managed in clinical practice before the availability of CAR-T

cell treatment.

Patients and Methods

Patients. This

single-center, non-interventional, retrospective study analyzed the

outcome of all consecutive patients with relapsed DLBCL or patients

with high-risk presentation who underwent HDCT/ASCT between May 2005

and February 2019 at the University Hospital of Bern, Switzerland.

Treatment for DLBCL prior to HDCT/ASCT was applied in various referring

centers in Switzerland. Inclusion criteria were the diagnosis of either

high-risk DLBCL or relapsed DLBCL (with the subtypes shown in Table 1),

age of at least 18 years at first diagnosis, and sufficient information

on remission status after HDCT with ASCT. Patients with high-risk

presentation who were consolidated with ACST after first-line therapy

had to have a chemo-sensitive disease and had to achieve partial or

complete remission before consolidation.

|

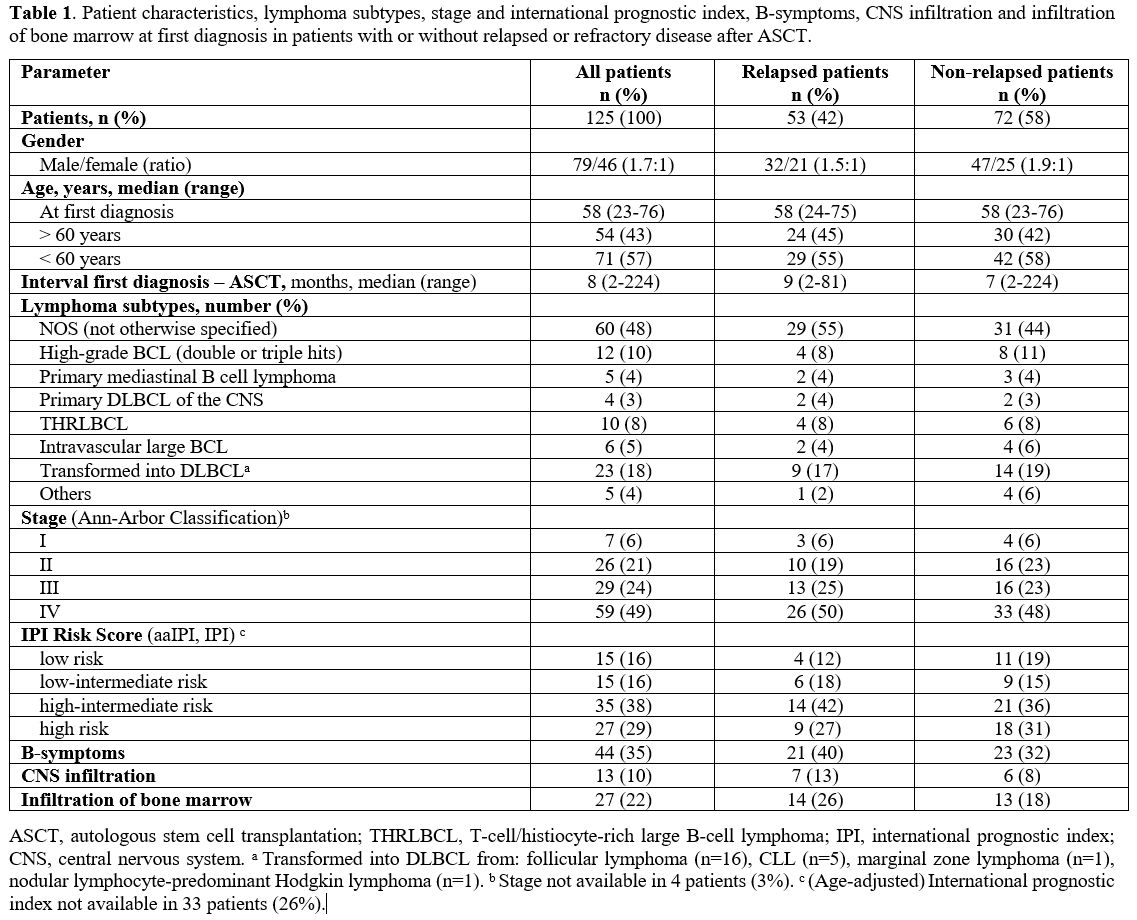

- Table

1. Patient characteristics, lymphoma subtypes, stage and international

prognostic index, B-symptoms, CNS infiltration and infiltration of bone

marrow at first diagnosis in patients with or without relapsed or

refractory disease after ASCT.

|

Patients

were divided into two groups depending on their response to HDCT/ASCT.

The first group included patients with r/r disease after ASCT. The

second group comprised patients in ongoing remission without relapse of

DLBCL. All patients gave written informed consent, and this analysis

was approved by the local ethics committee of Bern, Switzerland.

Data source.

Clinical data for this study were collected from the local electronic

patient information system at the University Hospital Bern.

Furthermore, information was obtained from the local Management and

Resource System for Stem Cell Transplantation (MARCELL), providing

specific information on the stem cell transplantation procedures at the

University Hospital Bern.

Methods and Definitions. At first diagnosis, patients were staged according to the Ann Arbor classification,[30] and the international prognostic index (IPI) was used for risk stratification.[31]

Remission status was determined according to the revised response

criteria of the international working group for malignant lymphoma

before ASCT, 100 days after ASCT, and at annual follow-up.[32]

Response was classified as complete remission (CR), partial remission

(PR), stable disease (SD), and progressive disease (PD). CR was defined

as complete disappearance of clinical lymphoma evidence and

disease-related symptoms. PR was defined as a measurable disease

reduction of at least 50% and no occurrence of new lesions. Patients

with SD did not fulfill CR/PR or PD criteria. The occurrence of new

lesions or the increase of previously reported tumor masses by more

than 50% were defined as PD.[32,33]

The primary

endpoints were overall survival and progression-free survival. PFS was

defined as the time from ASCT until the first evidence of

relapse/progression or death from any cause. OS was defined as the time

from ASCT until death from any cause.

Statistical analysis.PFS

and OS were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Survival

differences between subgroups were identified by the log-rank test.

Univariate analysis was calculated for the factors: age at first

diagnosis, transformed lymphoma vs. de novo origin, presence of

B-symptoms at first diagnosis, bone marrow infiltration at first

diagnosis, radiotherapy administered during first or second-line

therapy, the interval between first-line therapy until

relapse/progression, the performance of CD34+ cell positive selection,

remission status at ASCT, the interval from ASCT to

relapse/progression, number of therapies prior to HDCT/ASCT, and number

of further therapies after post-ASCT relapse. P values of <0.05 were

assumed to be statistically significant. All data were conducted with

GraphPad Prism, and calculations were done by Excel.

Results

Patient characteristics.

This study included 125 consecutive patients with DLBCL who received

HDCT/ASCT either as first-line consolidation due to high-risk

presentation or as salvage therapy for relapsed DLBCL. Clinical

characteristics at first diagnosis are summarized in Table 1.

63% of the patients were male. The median age at first diagnosis was 58

years (range, 23-76 years). DLBCL NOS (not otherwise specified) was the

most common lymphoma subtype (48%). B-symptoms at first diagnosis were

present in 44 patients (35%), bone marrow infiltration and central

nervous system infiltration were observed in 27 (22%) and 13 patients

(10%), respectively.

Transformed lymphoma was present in 23

patients, with 16 (70%) being initially diagnosed with follicular

lymphoma, five (22%) with CLL, and one patient (4%) each with marginal

zone lymphoma or nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma. 73%

of the patients had advanced-stage disease with Ann Arbor stages III

(29 pts; 24%) or IV (59 pts; 49%). IPI for risk stratification at first

diagnosis was a high-intermediate risk in 35 patients (38%) and high

risk in 27 patients (29%).

As described above, patients were

distributed into two groups depending on the disease control (relapse

or progression) after HDCT/ASCT. Both cohorts were comparable regarding

age, gender, lymphoma subtypes, stages, and IPI at first diagnosis (Table 1).

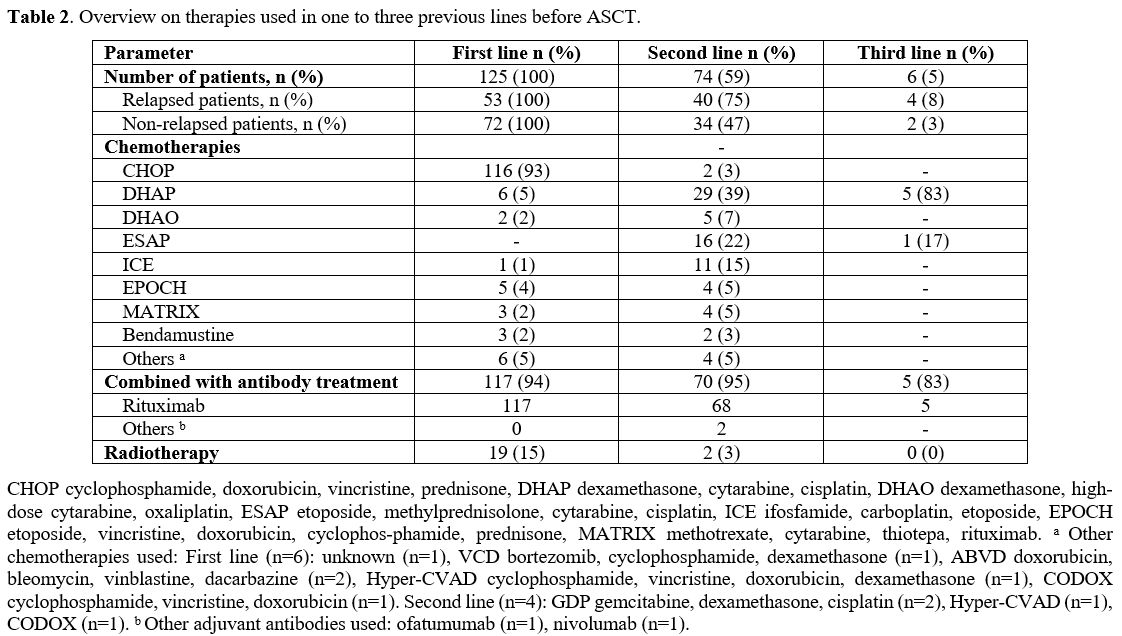

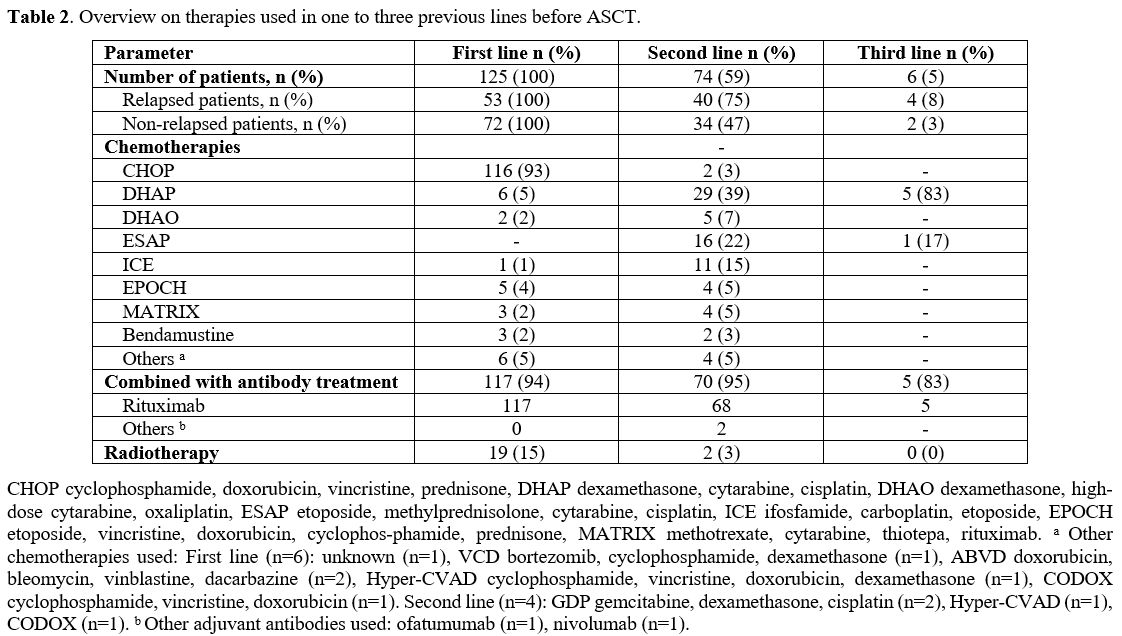

Previous therapies before ASCT. Details on the treatment given before HDCT/ASCT are presented in Table 2.

Patients had a median of two treatment lines before ASCT (range 1-3).

Fifty-one patients (41%) received HDCT/ASCT after only one line of

therapy due to high-risk presentation, 68 patients (55%) after two, and

6 patients (5%) after three lines of treatment. For first-line

treatment, 93% of patients received the CHOP regimen, and 94% of CHOP

chemotherapies were combined with rituximab.

|

- Table 2. Overview on therapies used in one to three previous lines before ASCT.

|

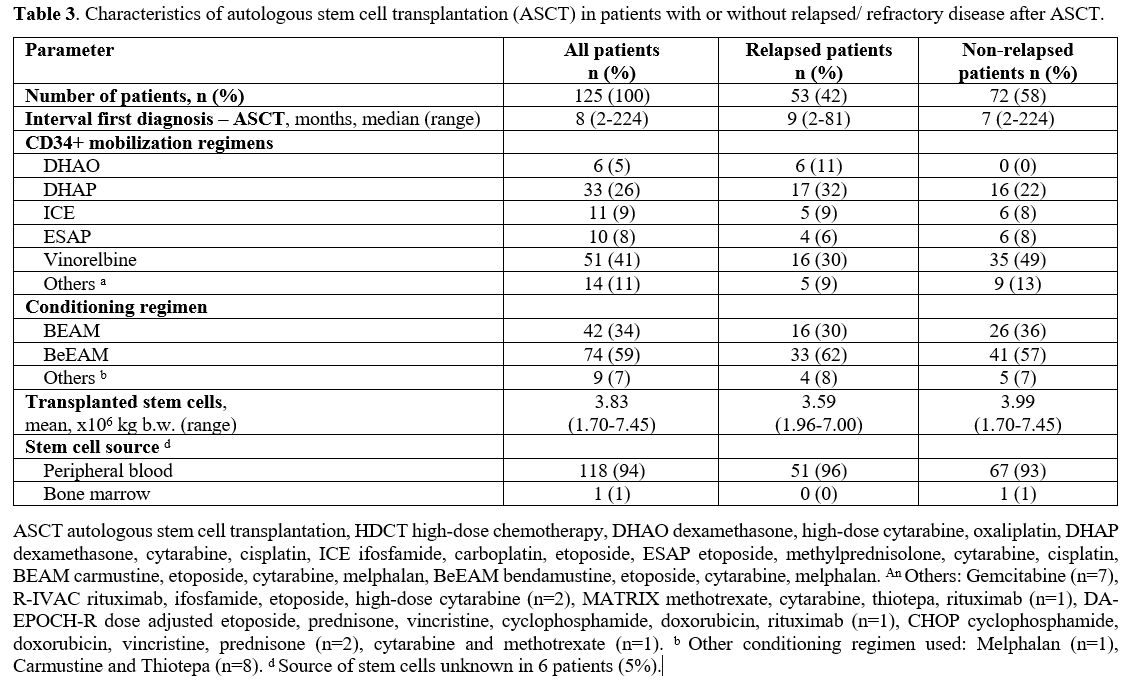

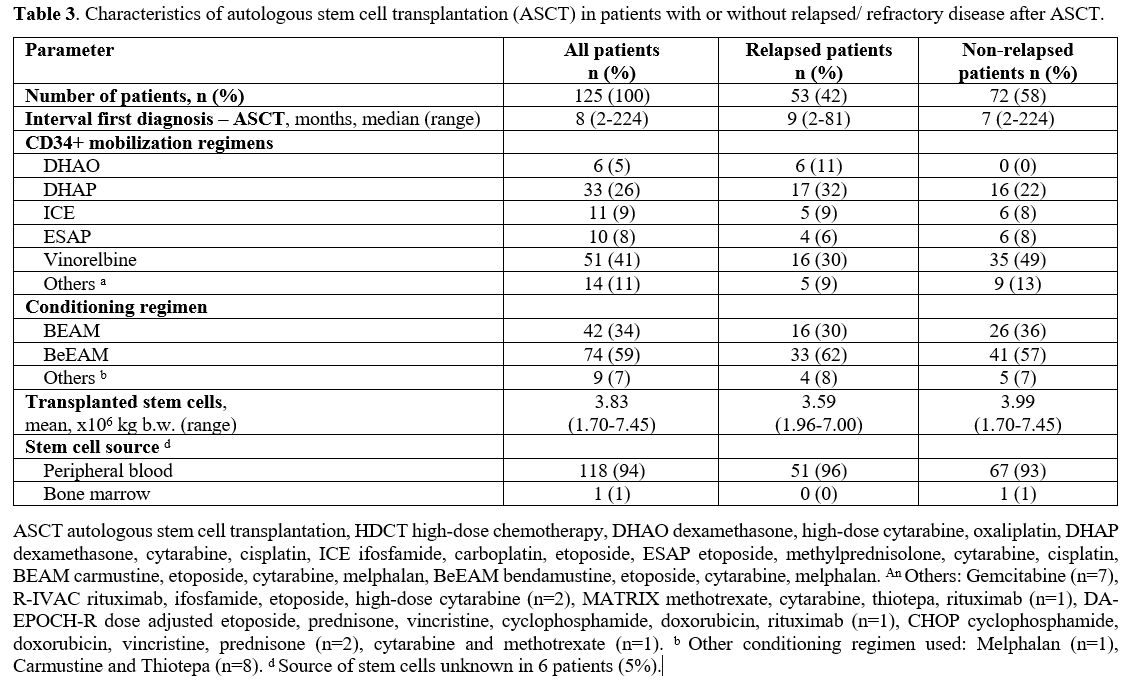

High-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation.

HDCT/ASCT was performed after a median interval of 8 months from the

initial diagnosis. Conditioning regimens in 93% were either the BeEAM

(59%) or BEAM (34%). 7% of patients received either melphalan alone or

the combination of carmustine and thiotepa as conditioning treatment.

Detailed information on HDCT and ASCT is presented in Table 3.

|

- Table 3. Characteristics

of autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) in patients with or

without relapsed/ refractory disease after ASCT.

|

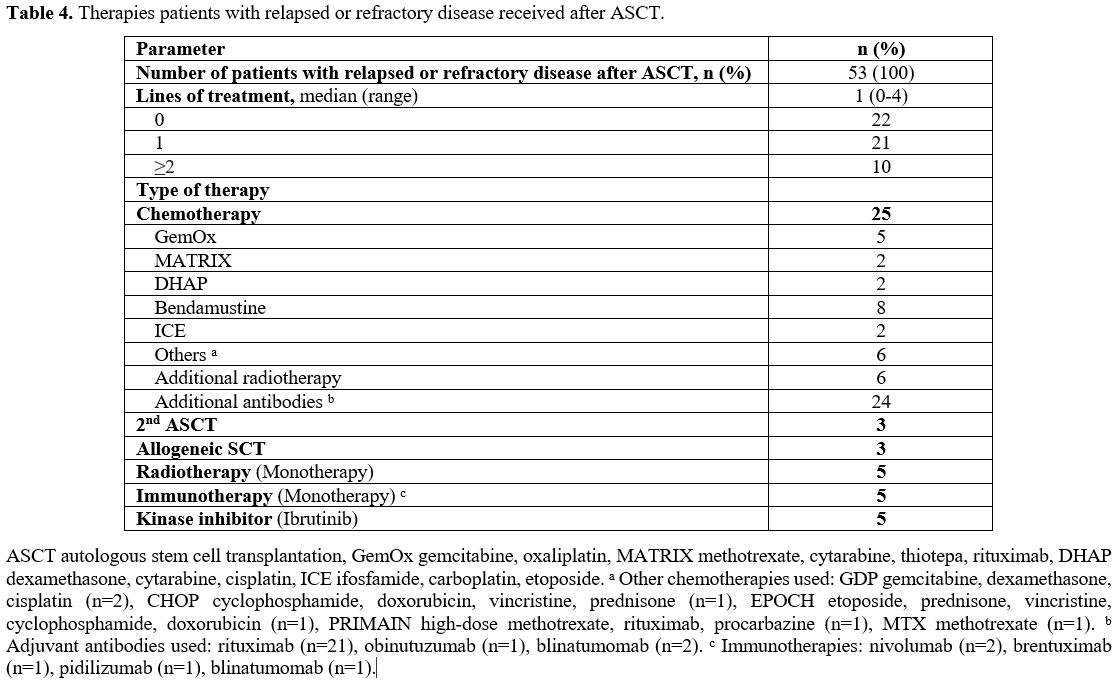

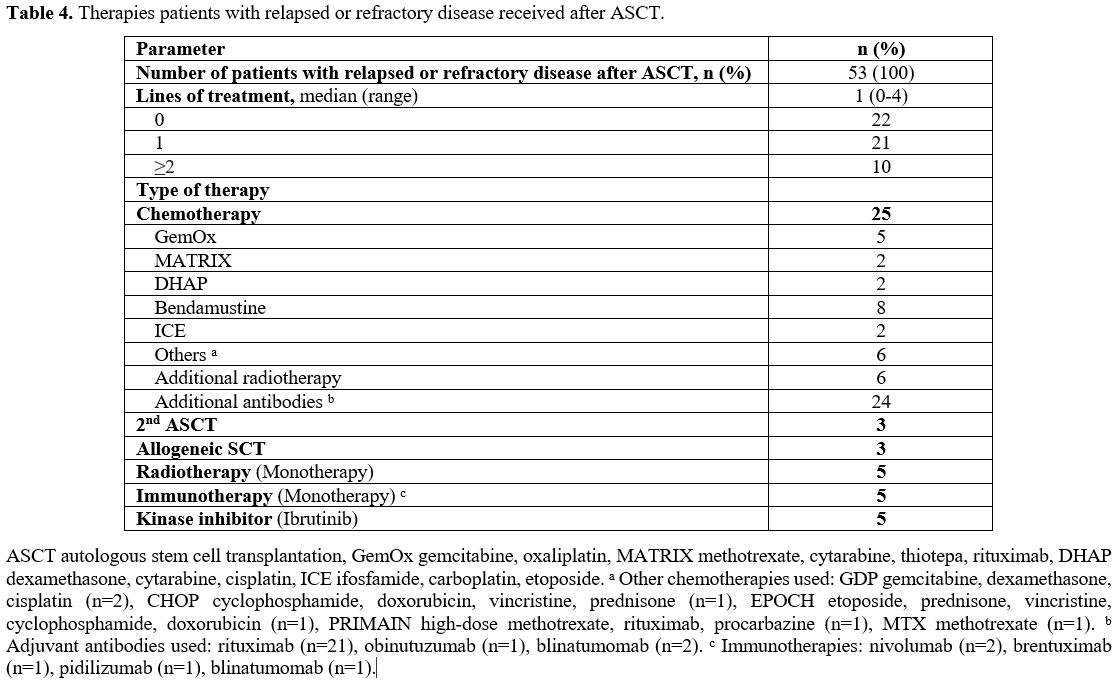

Salvage therapy at relapse/progression after HDCT/ASCT.

Fifty-three patients (42%) developed relapse or progression after a

median interval of 3 months from ASCT (range 1 to 145 months).

Thirty-one patients - 58% of all patients with relapse/progression,

respectively - received further therapies. Twenty-one patients were

treated with one therapy line, and ten patients had two to four

treatment lines for relapsing disease after ASCT, with a median of one

therapy line (range 0 to 4 lines). 22 patients had no further therapy

due to poor general condition or by the patient’s wish.

The

following further therapies were administered: cytotoxic chemotherapy

(25 patients), radiotherapy (five patients), second HDCT/ASCT (three

patients), and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

(three patients). Three patients received immunotherapy targeting PD-1

(nivolumab: two patients; pidilizumab: one patient), one patient had

blinatumomab, five patients were given ibrutinib, and one patient

received the antibody-drug conjugate brentuximab vedotin, as listed in Table 4.

|

- Table 4. Therapies patients with relapsed or refractory disease received after ASCT.

|

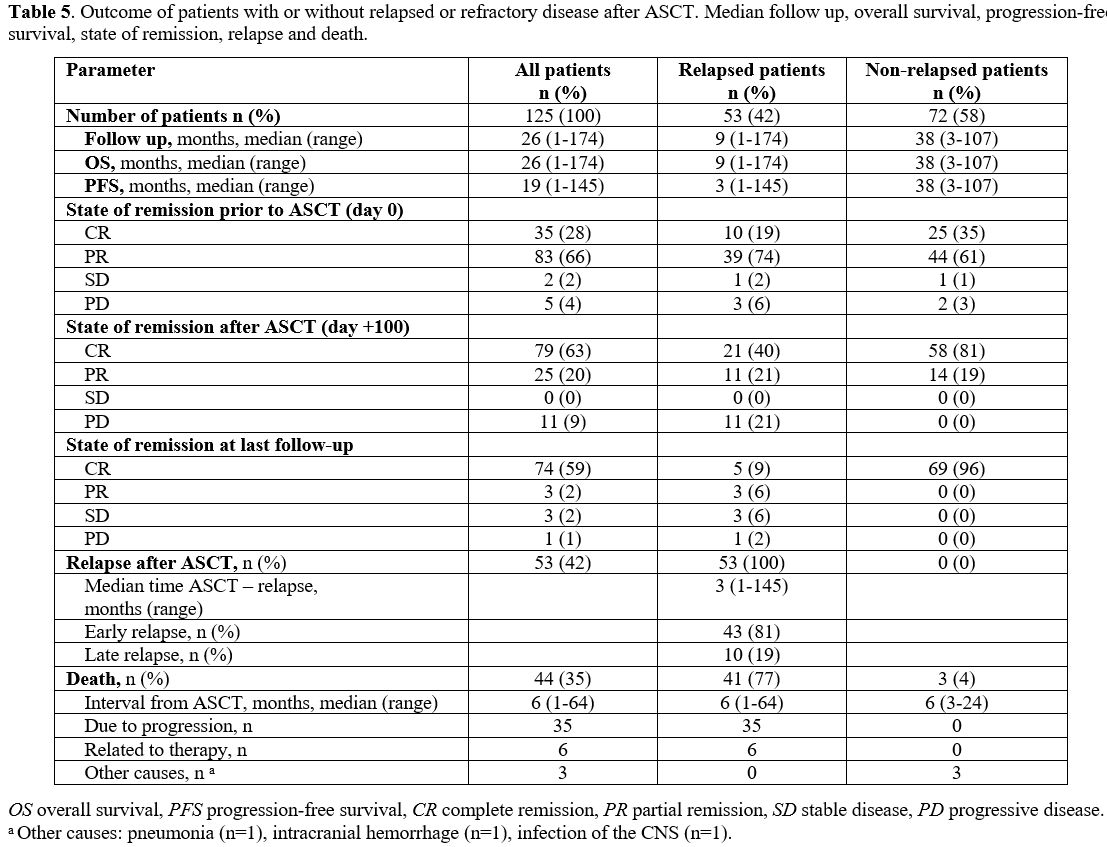

Outcome. Details on the outcome of the patients after HDCT/ASCT are depicted in Table 5.

The median follow-up of the entire patient cohort was 26 months.

Forty-four patients (35%) died after a median of six months (range

1-64), 35 (80% of the patients) due to disease progression, six due to

therapy-related reasons (in five cases due to HDCT associated

toxicities, and in one case related to subsequent allogeneic

transplantation) and six from other causes.

|

- Table 5. Outcome of

patients with or without relapsed or refractory disease after ASCT.

Median follow up, overall survival, progression-free survival, state of

remission, relapse and death.

|

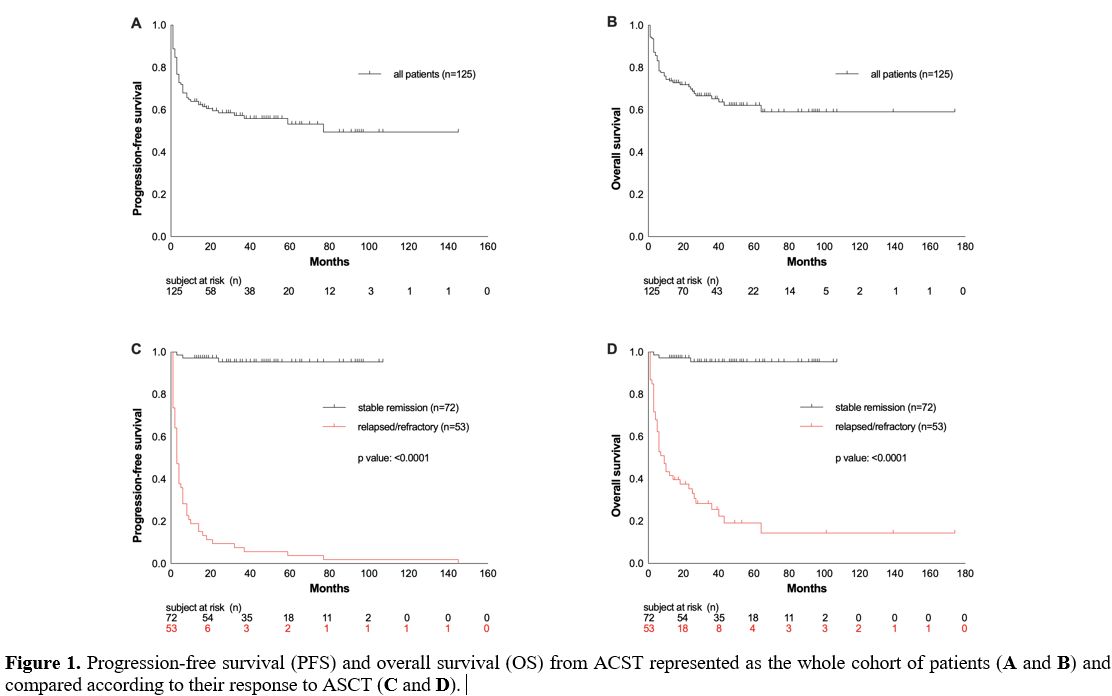

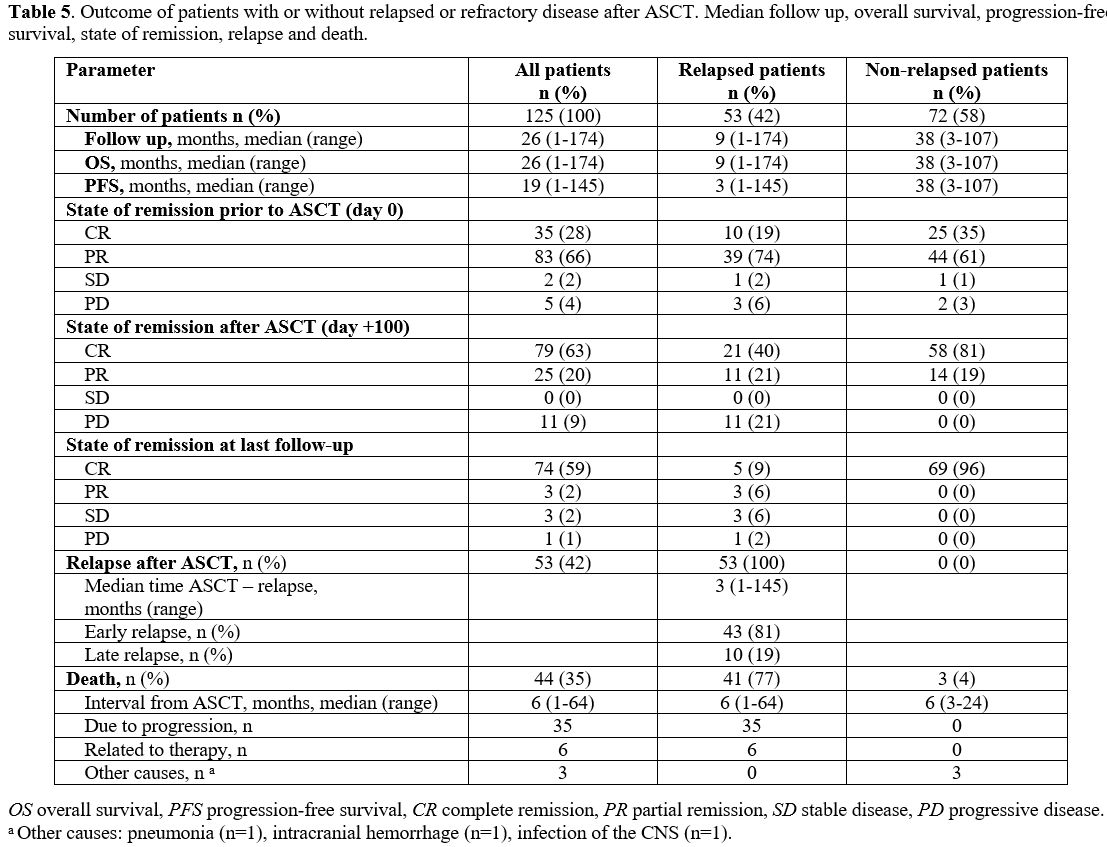

The median OS of the entire population was 26 months, and the OS rate at the last follow-up was 65% (Figure 1C).

As expected, patients with r/r disease after ASCT had worse overall

survival compared to patients in ongoing remission (OS at last

follow-up: 23% vs. 96%; median OS: 9 vs. 38 months; p <0.0001; Figure 1D).

Progression-free survival (PFS) of the entire cohort at the last

follow-up was 55%, with a median duration of response of 19 months (Figure 1A). Relapsed or refractory disease occurred in 42% of patients after a median interval of 3 months.

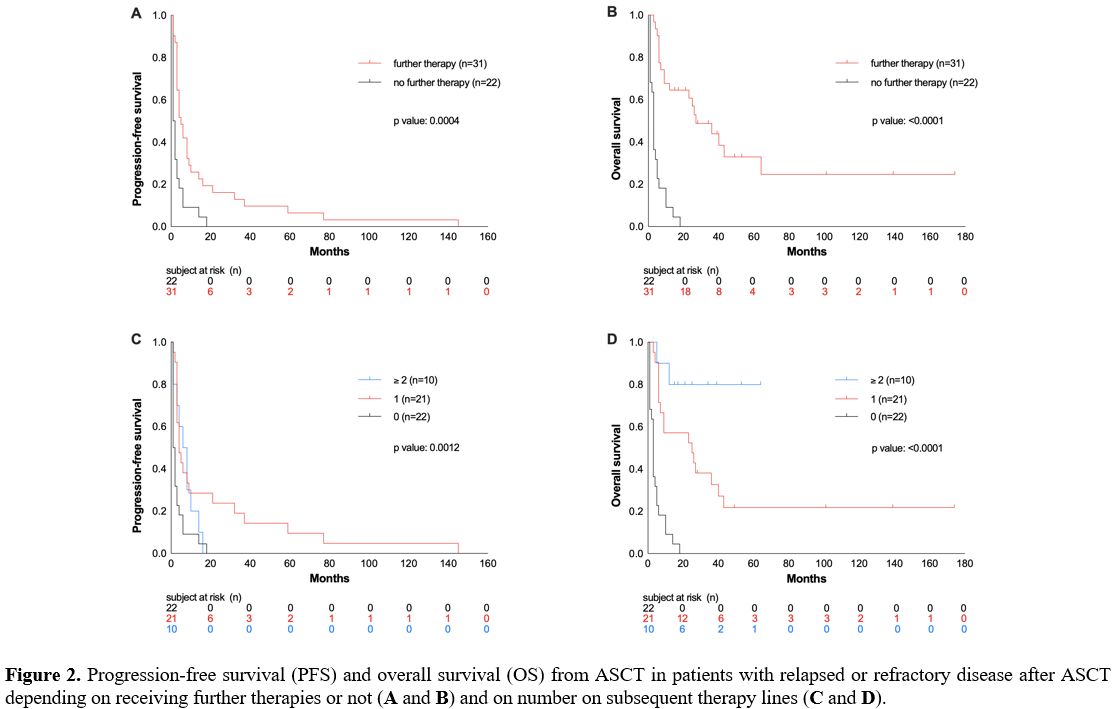

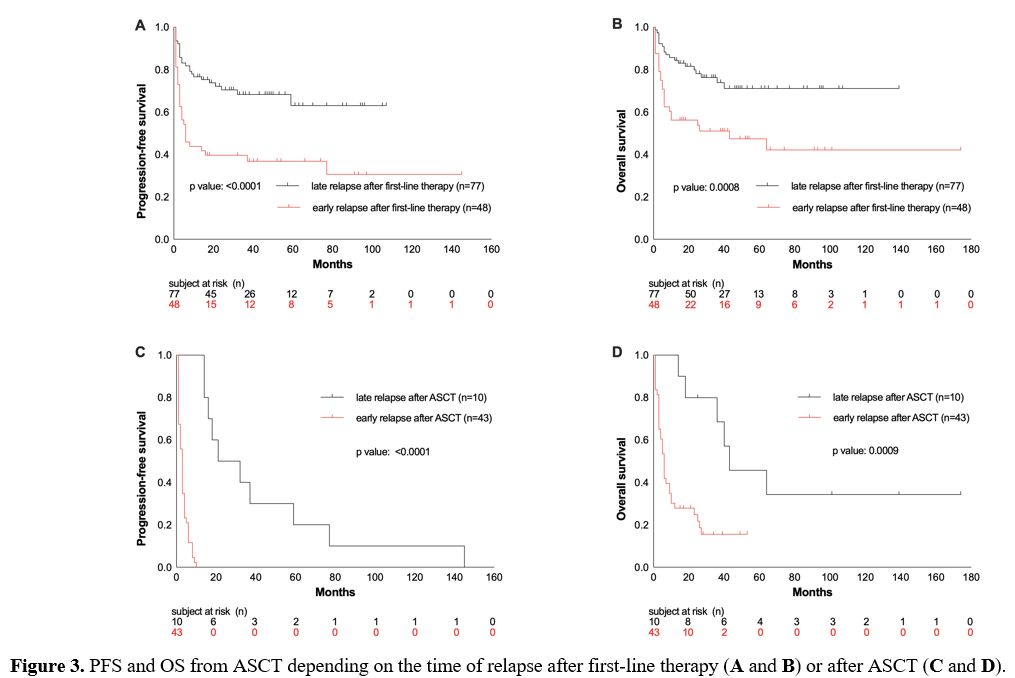

Four

factors were identified to be associated with survival rates: interval

of relapse from first-line therapy and interval from HDCT/ASCT, number

of therapies prior to HDCT/ASCT, and the number of treatment lines

after post-ASCT relapse. 38% of patients showed an early relapse after

first-line therapy, defined as relapsed disease or progression within

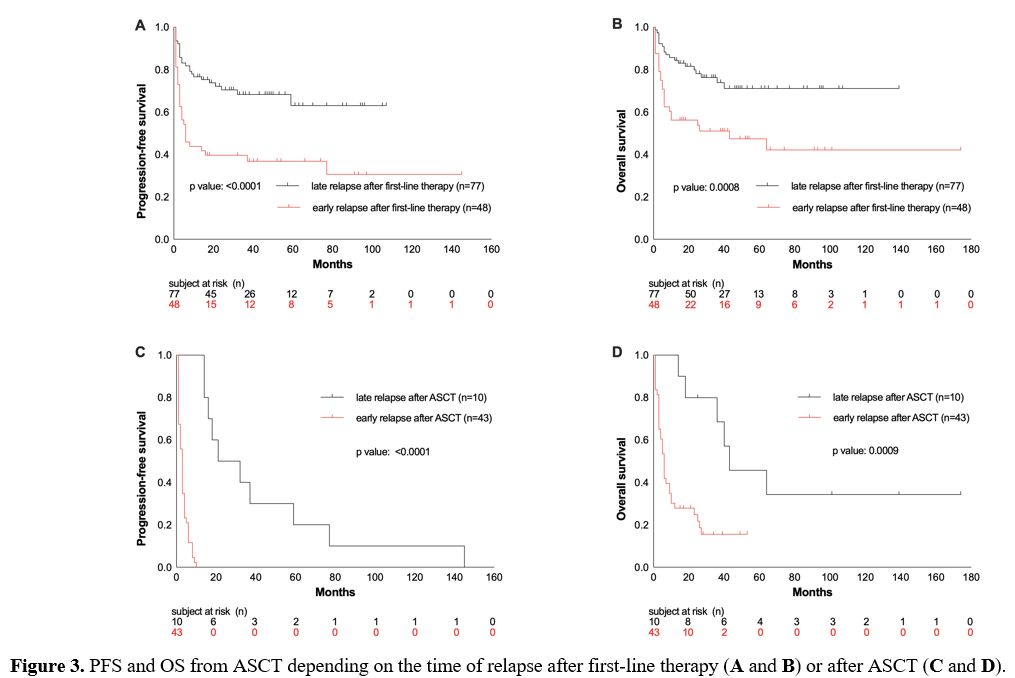

the first year. These patients had inferior OS and PFS compared to

patients who relapsed after 12 months or later (OS rate at 26 months:

48% vs. 75%, p = 0.0008; PFS rate: 33% vs. 69%, p < 0.0001; Figure 3A/B).

When

only patients with r/r disease (n=53) following HDCT/ASCT were

considered, early relapse or progression within the first 12 months

after ASCT occurred in 81% of these patients. 19% of the patients had a

late-onset relapse (an occurrence of relapse ≥ 12 months after ASCT).

Patients with early relapse or progression had lower OS than patients

with late onset of relapse post-ASCT (OS rate at 26 months: 19% vs.

40%, p= 0.0009, Figure 3D).

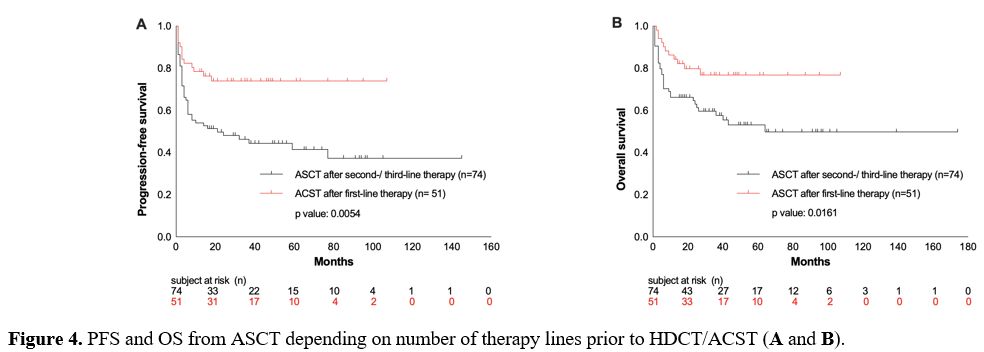

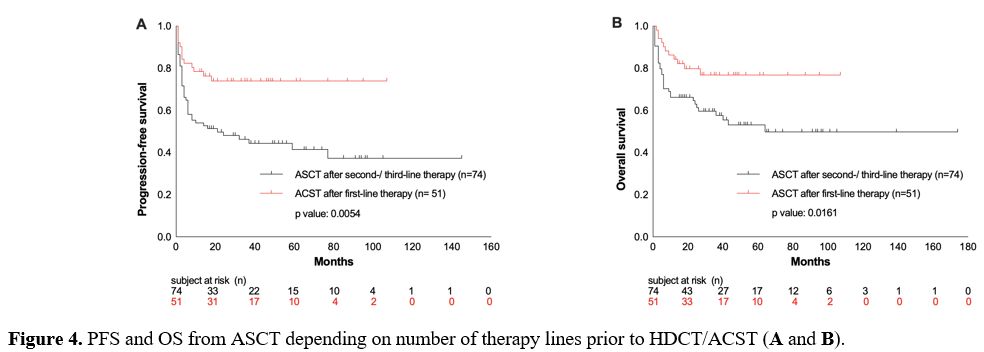

Comparing

the patients’ outcome regarding the number of therapies prior to HDCT/

ASCT, a significant benefit was observed in those patients who received

HDCT/ASCT after the first-line therapy because of high-risk

presentation (n= 51), compared to those patients who had two to three

lines of treatment prior to HDCT/ASCT (OS rate at 26 months: 78% vs.

55%, p= 0.0161; PFS rate: 75% vs. 42%, p= 0.0054; Figure 4 A/B).

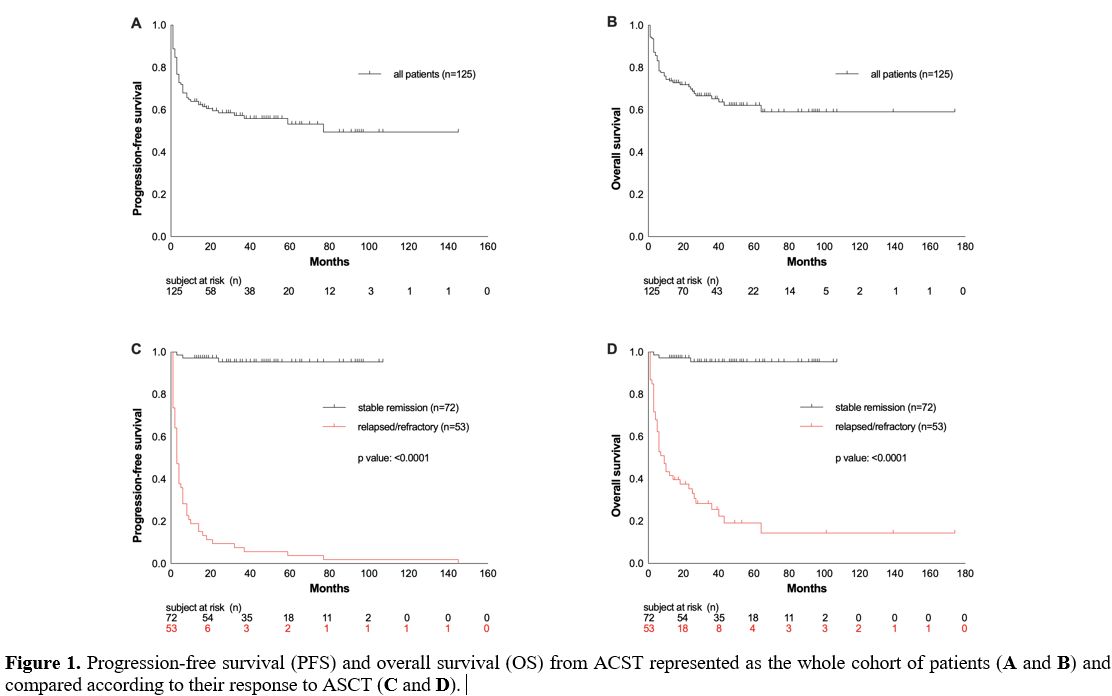

Considering

all patients with r/r disease following HDCT/ASCT, the OS rate was only

23% after a median follow-up of 26 months after ASCT. Patients who

received no other therapy despite relapse/progression after ASCT due to

poor general condition or according to the patient’s wish had an even

worse outcome compared to patients with additional treatment line(s) in

this situation (OS rate at 26 months 0% vs. 39%, p >0.0001, Figure 2A).

42% of patients received no further therapy, 40% were treated with one,

and 19% with two or more therapy lines, corresponding to OS rates of 0%

vs. 24% vs. 70% (p> 0.0001; Figure 2B). Thus, in relapsed patients, the OS was longer with an increasing number of therapy lines.

|

Figure 1. Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) from ACST represented as the whole cohort of patients (A and B) and compared according to their response to ASCT (C and D).

|

|

Figure

2. Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) from ASCT

in patients with relapsed or refractory disease after ASCT depending on

receiving further therapies or not (A and B) and on number on subsequent therapy lines (C and D).

|

|

Figure 3. PFS and OS from ASCT depending on the time of relapse after first-line therapy (A and B) or after ASCT (C and D).

|

|

Figure 4. PFS and OS from ASCT depending on number of therapy lines prior to HDCT/ACST (A and B). |

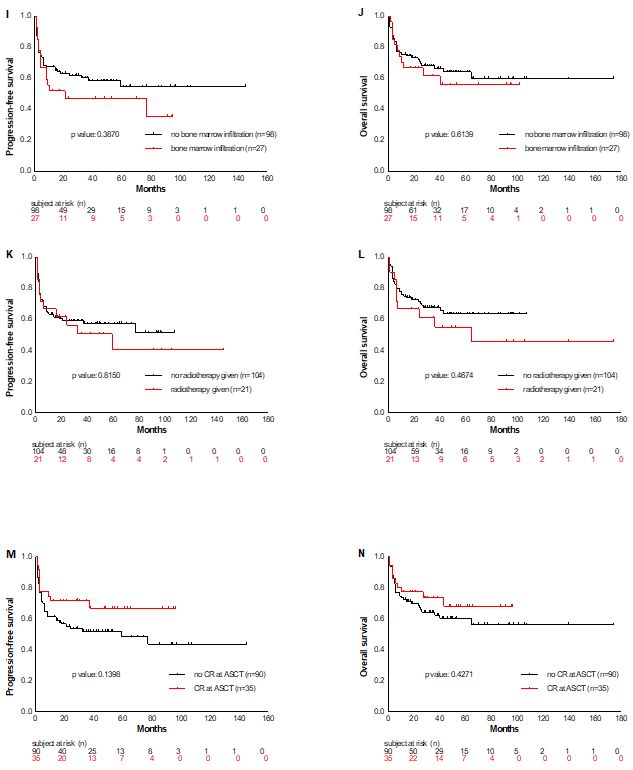

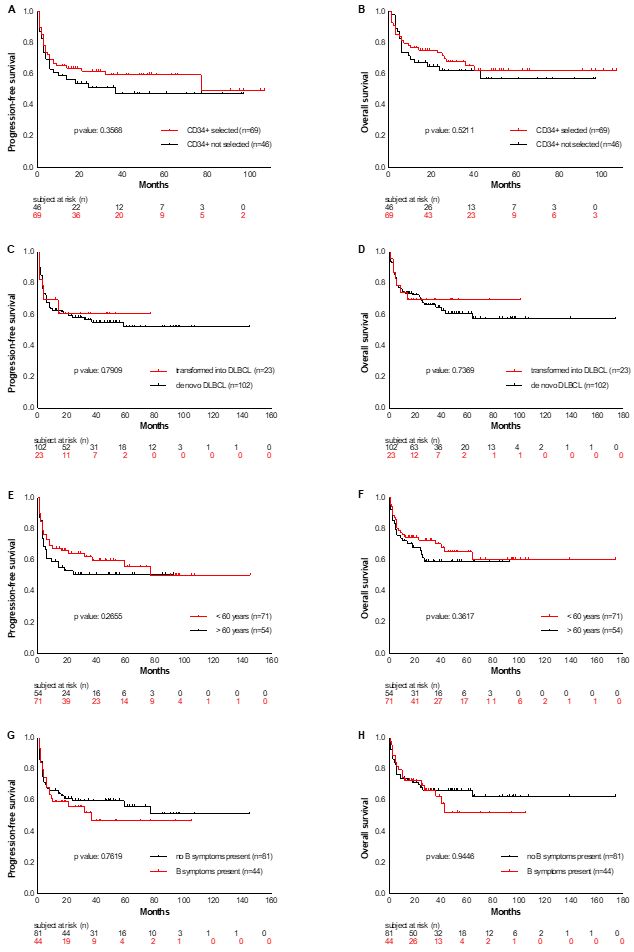

No differences were

detected in OS and PFS rates of specific subsets when data were

adjusted for the following variables: de novo versus transformed

lymphoma (OS p=0.7369; PFS p=0.7909), age higher/lower than 60 years

(OS p= 0.3617; PFS p= 0.2655), B-symptoms present at first diagnosis

yes/no (OS p=0.9446; PFS p=0.7619), bone marrow infiltration present at

first diagnosis yes/no (OS p=0.6139; PFS p=0.3870), radiotherapy

administered before ASCT yes/no (OS p=0.4674; PFS p=0.8150), and CR at

ASCT yes/no (OS p=0.4271; PFS p=0.1398) (Supplementary material, Figure S1).

Discussion

Considering the introduction of CAR-T cell therapies for aggressive lymphatic malignancies in Europe and elsewhere,[24,25]

we aimed to further characterize the outcomes of patients with DLBCL

with a specific focus on those with failure after HDCT/ASCT. We

retrospectively investigated a cohort of 125 patients with DLBCL

treated with HDCT/ASCT in a single academic/ tertiary center and

studied, in particular, the subset of patients who relapsed or

developed progression following HDCT/ASCT and who could have benefited

from CAR-T therapy, had it then been available.

Confirming reports

by others, the present study demonstrates that HDCT, followed by ASCT,

provides excellent long-term outcomes in patients with relapsed or

refractory DLBCL, achieving stable remission after this salvage therapy

option.[9,34,35] In our analysis

comprising 125 recipients of HDCT/ASCT due to relapsed DLBCL or

high-risk presentation, the ORR was 61% for the total cohort. That 55%

of patients in ongoing remission following HDCT/ASCT showed encouraging

OS and PFS of 96% with a median duration of 38 months.

In

contrast, the prognosis for patients with r/r disease after HDCT/ASCT

is poor, especially in those with characteristics such as high IPI or

early relapse within 12 months following ASCT.[11,34]

In our study, 42% of patients developed relapses or showed progression

after HDCT/ASCT. Although 58% of these patients with failure of

HDCT/ASCT received other therapeutic approaches, 77% rapidly died after

a median interval of 6 months, mostly due to lymphoma progression.

Likewise, in the CORAL study, 29% of patients with r/r DLBCL after ASCT

had poor survival, with a median OS of 10 months and a 1-year OS of

39.1%.[35]

We evaluated the impact of various

parameters on the outcomes of our HDCT/ASCT cohort. Significant impact

on survival could only be verified for the duration of the response to

first-line therapy, the duration of response after HDCT/ASCT, the

number of therapies prior to HDCT/ASCT, and the number of subsequent

therapies after post-ASCT relapse. We documented a median interval to

progression following ASCT of only 3 months, and 81% of relapses

occurred within 12 months after ASCT, demonstrating that DLBCL relapses

are associated with rapid kinetics, early manifesting after HDCT/ASCT.

Furthermore, the OS rate was only 19% in patients with early relapses

(<12 months) post-ASCT, as compared to late relapses (≥12 months

after ASCT) with an OS rate of 40%. These results correspond with

previous studies demonstrating early relapses following ASCT in 65-80%

of patients, associated with a significantly worse OS compared to later

time points of relapse.[12,36] Other parameters such as the histopathological origin (transformed vs. de novo DLBCL) [37-41] and CD34+ selection[42-45] had no significant impact on the prognosis of the recipients of HDCT/ASCT in our cohort.

Treatment

options for patients with r/r DLBCL following ASCT were so far limited.

Allogeneic stem cell transplantation may provide a certain graft versus

lymphoma effect.[46-48] However, only a few DLBCL

patients are, in fact, candidates for this approach due to its high

transplant-related mortality and high relapse rates. Only three

patients in our cohort received an allogeneic SCT, which is

representative of the limited use of this option for r/r DLBCL patients.

CAR-T cell therapies, recently introduced, offer patients with r/r DLBCL a promising new option with CR rates of up to 58%.[24,49,50] In several studies, ORR of 52-85% with 40-58% CR rates were achieved by CAR-T cell therapy in patients with r/r DLBCL.[21,24-26,51,52] However, long-term outcomes will still be awaited in the next decades.

In addition, novel immunotherapies such as polatuzumab vedotin,[53] tafasitamab,[54]

glofitamab, or mosunetuzumab are additional promising new options for

DLBCL patients ineligible for HDCT/ASCT or for those whom CAR-T therapy

is no option due to its toxicity, or due to its logistic or financial

obstacles.

An obvious limitation of our study is its

retrospective single-center design covering a large timespan, including

various DLBCL subtypes, heterogeneity in conditioning regimen, and

inevitable lack of some data in a few patients. Nevertheless, our study

demonstrates the adverse prognosis of DLBCL patients after HDCT/ASCT

failure and the limited efficacy of subsequent therapeutic approaches,

including a second HDCT/ASCT, allogeneic SCT, radiation, cytotoxic

treatment, and traditional monoclonal antibody therapies. Our study

emphasizes the urgent need to make CAR-T cell therapies available to

all patients with r/r DLBCL following HDCT/ASCT failure.[21]

References

- Pfreundschuh M, Schubert J, Ziepert M, et al. Six

versus eight cycles of bi-weekly CHOP-14 with or without rituximab in

elderly patients with aggressive CD20+ B-cell lymphomas: a randomised

controlled trial (RICOVER-60). Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(2):105-116.

doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70002-0 https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70002-0 PMid:18226581

- Pfreundschuh

M, Trümper L, Österborg A, et al. CHOP-like chemotherapy plus rituximab

versus CHOP-like chemotherapy alone in young patients with

good-prognosis diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: a randomised controlled

trial by the MabThera International Trial (MInT) Group. Lancet Oncol.

2006;7(5):379-391. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70664-7 https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70664-7 PMid:16648042

- Habermann

TM, Weller EA, Morrison VA, et al. Rituximab-CHOP versus CHOP alone or

with maintenance rituximab in older patients with diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(19):3121-3127.

doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1003 https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1003 PMid:16754935

- Sehn

LH, Donaldson J, Chhanabhai M, et al. Introduction of combined CHOP

plus rituximab therapy dramatically improved outcome of diffuse large

B-cell lymphoma in British Columbia. J Clin Oncol.

2005;23(22):5027-5033. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.09.137 https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2005.09.137 PMid:15955905

- Tilly

H, Gomes da Silva M, Vitolo U, et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

(DLBCL): ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and

follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(Supplement 5):vii78-vii82.

doi:10.1093/annonc/mdv304 https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdv304 PMid:26314773

- Feugier

P, Van Hoof A, Sebban C, et al. Long-term results of the R-CHOP study

in the treatment of elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma: A study by the groupe d'etude des lymphomes de l'adulte. J

Clin Oncol. 2005;23(18):4117-4126. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.09.131 https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2005.09.131 PMid:15867204

- Coiffier

B, Lepage E, Brière J, et al. CHOP Chemotherapy plus Rituximab Compared

with CHOP Alone in Elderly Patients with Diffuse Large-B-Cell Lymphoma.

N Engl J Med. 2002;346(4):235-242. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa011795 https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa011795 PMid:11807147

- Coiffier

B, Sarkozy C. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: R-CHOP failure-what to do?

Hematology. 2016;2016(1):366-378. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2016.1.366 https://doi.org/10.1182/asheducation-2016.1.366 PMid:27913503 PMCid:PMC6142522

- Philip

T, Guglielmi C, Hagenbeek A, et al. Autologous Bone Marrow

Transplantation as Compared with Salvage Chemotherapy in Relapses of

Chemotherapy-Sensitive Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma. N Engl J Med.

2002;333(23):1540-1545. doi:10.1056/nejm199512073332305 https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199512073332305 PMid:7477169

- Camus

V, Tilly H. Managing early failures with R-CHOP in patients with

diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Expert Rev Hematol.

2017;10(12):1047-1055. doi:10.1080/17474086.2016.1254547 https://doi.org/10.1080/17474086.2016.1254547 PMid:27791447

- Gisselbrecht

C, Van Den Neste E. How I manage patients with relapsed/refractory

diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2018;182(5):633-643.

doi:10.1111/bjh.15412 https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.15412 PMid:29808921 PMCid:PMC6175435

- Nagle

SJ, Woo K, Schuster SJ, et al. Outcomes of patients with

relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with progression of

lymphoma after autologous stem cell transplantation in the rituximab

era. Am J Hematol. 2013;88(10):890-894. doi:10.1002/ajh.23524 https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.23524 PMid:23813874

- Friedberg JW. Relapsed / Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Am Soc Hematol. Published online 2011:498-505. https://doi.org/10.1182/asheducation-2011.1.498 PMid:22160081

- Gilli

S, Novak U, Taleghani BM, et al. BeEAM conditioning with

bendamustine-replacing BCNU before autologous transplantation is safe

and effective in lymphoma patients. Ann Hematol. 2017;96(3):421-429.

doi:10.1007/s00277-016-2900-y https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-016-2900-y PMid:28011985

- Prediletto

I, Farag SA, Bacher U, et al. High incidence of reversible renal

toxicity of dose-intensified bendamustine-based high-dose chemotherapy

in lymphoma and myeloma patients. Bone Marrow Transplant.

2019;54(12):1923-1925. doi:10.1038/s41409-019-0508-2 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-019-0508-2 PMid:30890768

- Betticher

C, Bacher U, Legros M, et al. Prophylactic corticosteroid use prevents

engraftment syndrome in patients after autologous stem cell

transplantation. Hematol Oncol. 2021;39(1):97-104. doi:10.1002/hon.2813

https://doi.org/10.1002/hon.2813 PMid:32979278

- Vose

JM, Bierman PJ, Anderson JR, et al. Progressive disease after high-dose

therapy and autologous transplantation for lymphoid malignancy:

clinical course and patient follow-up. Blood. 1992;80(8):2142-2148. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.V80.8.2142.2142 PMid:1356515

- Robinson

SP, Boumendil A, Finel H, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation

for relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Efficacy in the

rituximab era and comparison to first allogeneic transplants. A report

from the EBMT Lymphoma Working Party. Bone Marrow Transplant.

2016;51(3):365-371. doi:10.1038/bmt.2015.286 https://doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2015.286 PMid:26618550

- Eicher

F, Mansouri Taleghani B, Schild C, Bacher U, Pabst T. Reduced survival

after autologous stem cell transplantation in myeloma and lymphoma

patients with low vitamin D serum levels. Hematol Oncol.

2020;38(4):523-530. doi:10.1002/hon.2774 https://doi.org/10.1002/hon.2774 PMid:32594534

- Skrabek

P, Assouline S, Christofides A, et al. Emerging therapies for the

treatment of relapsed or refractory diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Curr

Oncol. 2019;26(4):253-265. doi:10.3747/co.26.5421 https://doi.org/10.3747/co.26.5421 PMid:31548805 PMCid:PMC6726277

- Sermer D, Brentjens R. CAR T‐cell therapy: Full speed ahead. Hematol Oncol. 2019;37(S1):95-100. doi:10.1002/hon.2591 https://doi.org/10.1002/hon.2591 PMid:31187533

- Chavez

JC, Locke FL. A Possible Cure for Refractory DLBCL: CARs Are Headed in

the Right Direction. Mol Ther. 2017;25(10):2241-2243.

doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.09.005 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.09.005 PMid:28941574 PMCid:PMC5628929

- Lekakis

LJ, Moskowitz CH. The Role of Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation in

the Treatment of Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma in the Era of CAR-T Cell

Therapy. HemaSphere. 2019;3(6). doi:10.1097/HS9.0000000000000295 https://doi.org/10.1097/HS9.0000000000000295 PMid:31976472 PMCid:PMC6924546

- Schuster

SJ, Bishop MR, Tam CS, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in Adult Relapsed or

Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med.

2018;380(1):45-56. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1804980 https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1804980 PMid:30501490

- Neelapu

SS, Locke FL, Bartlett NL, et al. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel CAR T-Cell

Therapy in Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med.

2017;377(26):2531-2544. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1707447 https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1707447 PMid:29226797 PMCid:PMC5882485

- Abramson

JS, Palomba ML, Gordon LI, et al. Lisocabtagene maraleucel for patients

with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphomas (TRANSCEND NHL 001):

a multicentre seamless design study. The Lancet.

2020;396(10254):839-852. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31366-0 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31366-0 PMid:32888407

- Titov

A, Petukhov A, Staliarova A, et al. The biological basis and clinical

symptoms of CAR-T therapy-associated toxicites. Cell Death Dis.

2018;9(9). doi:10.1038/s41419-018-0918-x https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-018-0918-x PMid:30181581 PMCid:PMC6123453

- Bishop

MR, Maziarz RT, Waller EK, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in

relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients without

measurable disease at infusion. Blood Adv. 2019;3(14):2230-2236.

doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000151 https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000151 PMid:31332046 PMCid:PMC6650727

- Pabst

T, Joncourt R, Shumilov E, et al. Analysis of IL-6 serum levels and CAR

T cell-specific digital PCR in the context of cytokine release

syndrome. Exp Hematol. 2020;88:7-14.e3.

doi:10.1016/j.exphem.2020.07.003 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exphem.2020.07.003 PMid:32673688

- Carbone

PP, Kaplan HS, Musshoff K, Smithers DW, Tubiana M. Report of the

Committee on Hodgkin's Disease Staging Classification. Cancer Res.

1971;31(11):1860.

- Ziepert

M, Hasenclever D, Kuhnt E, et al. Standard international prognostic

index remains a valid predictor of outcome for patients with aggressive

CD20 + B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era. J Clin Oncol.

2010;28(14):2373-2380. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.26.2493 https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.26.2493 PMid:20385988

- Cheson

BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, et al. Revised response criteria for

malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(5):579-586.

doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2403 https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2403 PMid:17242396

- Cheson

BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, et al. Report of an international workshop

to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. NCI

Sponsored International Working Group. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin

Oncol. 1999;17(4):1244. doi:10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1244 https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1244 PMid:10561185

- Crump

M, Neelapu SS, Farooq U, et al. Outcomes in refractory diffuse large

B-cell lymphoma: Results from the international SCHOLAR-1 study. Blood.

2017;130(16):1800-1808. doi:10.1182/blood-2017-03-769620 https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2017-03-769620 PMid:28774879 PMCid:PMC5649550

- Van

Den Neste E, Schmitz N, Mounier N, et al. Outcomes of diffuse large

B-cell lymphoma patients relapsing after autologous stem cell

transplantation: An analysis of patients included in the CORAL study.

Bone Marrow Transplant. 2017;52(2):216-221. doi:10.1038/bmt.2016.213 https://doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2016.213 PMid:27643872

- González-Barca

E, Boumendil A, Blaise D, et al. Outcome in patients with diffuse large

B-cell lymphoma who relapse after autologous stem cell transplantation

and receive active therapy. A retrospective analysis of the Lymphoma

Working Party of the European Society for Blood and Marrow

Transplantation (. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2020;55(2):393-399.

doi:10.1038/s41409-019-0650-x https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-019-0650-x PMid:31541205

- Wagner-Johnston

ND, Link BK, Byrtek M, et al. Outcomes of transformed follicular

lymphoma in the modern era: a report from the National LymphoCare Study

(NLCS). Blood. 2015;126(7):851-857. doi:10.1182/blood-2015-01-621375 https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2015-01-621375 PMid:26105149 PMCid:PMC4543911

- Sorigue

M, Garcia O, Baptista MJ, et al. Similar prognosis of transformed and

de novo diffuse large B-cell lymphomas in patients treated with

immunochemotherapy. Med Clínica Engl Ed. 2017;148(6):243-249.

doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medcle.2017.03.004 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medcle.2017.03.004

- Ghesquières

H, Berger F, Felman P, et al. Clinicopathologic Characteristics and

Outcome of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphomas Presenting With an Associated

Low-Grade Component at Diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(33):5234-5241.

doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.07.5671 https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2006.07.5671 PMid:17043351

- Guirguis

HR, Cheung MC, Piliotis E, et al. Survival of patients with transformed

lymphoma in the rituximab era. Ann Hematol. 2014;93(6):1007-1014.

doi:10.1007/s00277-013-1991-y https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-013-1991-y PMid:24414374

- Montoto

S, Fitzgibbon J. Transformation of Indolent B-Cell Lymphomas. J Clin

Oncol. 2011;29(14):1827-1834. doi:10.1200/JCO.2010.32.7577 https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.32.7577 PMid:21483014

- Berger

MD, Branger G, Leibundgut K, et al. CD34+ selected versus unselected

autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with advanced-stage

mantle cell and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Res.

2015;39(6):561-567. doi:10.1016/j.leukres.2015.03.004 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leukres.2015.03.004 PMid:25890431

- Gribben

JG, Freedman AS, Neuberg D, et al. Immunologic Purging of Marrow

Assessed by PCR before Autologous Bone Marrow Transplantation for

B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(22):1525-1533.

doi:10.1056/NEJM199111283252201 https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199111283252201 PMid:1944436

- Sharp

JG, Kessinger A, Mann S, et al. Outcome of high-dose therapy and

autologous transplantation in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma based on the

presence of tumor in the marrow or infused hematopoietic harvest. J

Clin Oncol. 1996;14(1):214-219. doi:10.1200/JCO.1996.14.1.214 https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1996.14.1.214 PMid:8558200

- Williams

C D, Goldstone, A H,R M Pearce R M, Philip T, Hartmann O, Colombat P,

Santini G, Foulard L, C GN. Purging of bone marrow in autologous bone

marrow transplantation for non-Hodkin's lymphoma: a case-matches

comparsion with unpurged cases by the European Blood and Marrow

Transplant Lymphoma Registry. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(9):2454-2464. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1996.14.9.2454 PMid:8823323

- Klyuchnikov

E, Bacher U, Kroll T, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell

transplantation for diffuse large B cell lymphoma: Who, when and how.

Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49(1):1-7. doi:10.1038/bmt.2013.72 https://doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2013.72 PMid:23708703

- Doocey

RT, Toze CL, Connors JM, et al. Allogeneic haematopoietic stem-cell

transplantation for relapsed and refractory aggressive histology

non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2005;131(2):223-230.

doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05755.x https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05755.x PMid:16197454

- Van

Kampen RJW, Canals C, Schouten HC, et al. Allogeneic stem-cell

transplantation as salvage therapy for patients with diffuse large

B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma relapsing after an autologous stem-cell

transplantation: An analysis of the European Group for Blood and Marrow

Transplantation registry. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(10):1342-1348.

doi:10.1200/JCO.2010.30.2596 https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.30.2596 PMid:21321299

- Locke

FL, Ghobadi A, Jacobson CA, et al. Long-term safety and activity of

axicabtagene ciloleucel in refractory large B-cell lymphoma (ZUMA-1): a

single-arm, multicentre, phase 1-2 trial. Lancet Oncol.

2019;20(1):31-42. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30864-7 https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30864-7 PMid:30518502

- Abramson

JS, Gordon LI, Palomba ML, et al. Updated safety and long term clinical

outcomes in TRANSCEND NHL 001, pivotal trial of lisocabtagene

maraleucel (JCAR017) in R/R aggressive NHL. J Clin Oncol.

2018;36(15_suppl):7505-7505. doi:10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.7505 https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.7505

- Kochenderfer

JN, Somerville RPT, Lu T, et al. Lymphoma Remissions Caused by

Anti-CD19 Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells Are Associated With High

Serum Interleukin-15 Levels. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol.

2017;35(16):1803-1813. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.71.3024 https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.71.3024 PMid:28291388 PMCid:PMC5455597

- Locke

FL, Neelapu SS, Bartlett NL, et al. Phase 1 Results of ZUMA-1: A

Multicenter Study of KTE-C19 Anti-CD19 CAR T Cell Therapy in Refractory

Aggressive Lymphoma. Mol Ther. 2017;25(1):285-295.

doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2016.10.020 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2016.10.020 PMid:28129122 PMCid:PMC5363293

- Sehn

LH, Herrera AF, Flowers CR, et al. Polatuzumab vedotin in relapsed or

refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol.

2020;38(2):155-165. doi:10.1200/JCO.19.00172 https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.19.00172 PMid:31693429 PMCid:PMC7032881

- Salles

G, Duell J, González Barca E, et al. Tafasitamab plus lenalidomide in

relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (L-MIND): a

multicentre, prospective, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol.

2020;21(7):978-988. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30225-4 https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30225-4 PMid:32511983

Online Supplement

|

Supplementary Figure

S1. PFS and OS analyzed according to various parameters like presence

or absence of CD34+ stem cell selection (Figure A and B), transformed

versus de novo lymphoma (Figure C and D), age at first diagnosis <

versus ≥ 60 years (Figure E and F), presence or absence of b symptoms

(Figure G and H) and bone marrow infiltration (Figure I and J) at first

diagnosis, radiotherapy given during first- or second line therapy

(Figure K and L) and remission state at ASCT (Figure M and N).

|

[TOP]