Chiara Papalini1, Lucia Brescini2, Laura Curci1, Sabrina Bastianelli1, Francesco Barchiesi2, Andrea Giacometti2 and Daniela Francisci1.

1 Infectious Diseases Clinic, Santa Maria della Misericordia Hospital, Università degli Studi di Perugia, Perugia, Italy.

2 Biomedical Sciences and Public Health Department, Università Politecnica delle Marche, Ancona, Italy.

Published: May 1, 2023

Received: January 29, 2023

Accepted: April 17, 2023

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2023, 15(1): e2023027 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2023.027

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

To the editor

Kaposi

Sarcoma (KS) in people living with HIV (PLWH) is an AIDS-defining

malignancy implying endothelial cell proliferation. It can involve all

the organs but most frequently appears as purplish or brownish

mucocutaneous lesions. Herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8) is recognized as the

primum movens of the oncogenic pathway. Men who have Sex with Men (MSM)

and African inhabitants of the "KS belt" have the main risk factors for

HHV-8 infection and KS.[1-5] Antiretroviral therapy

(ART) has sensibly modified KS incidence. However, it is still one of

the most frequent neoplasms in PLWH.[1,3,6,7]

The

aim of this study is to report epidemiological and clinical features of

PLWH affected by KS and to analyze which variables, if any, influence

the mortality rate.

This retrospective observational study

included PLWH affected by KS attending the Infectious Diseases Clinics

of S. Maria della Misericordia Hospital of Perugia, Italy, or Torrette

Hospital of Ancona, Italy, from Jan 1, 2002, to Dec 31, 2022. The two

hospitals are the main health centers of two regions of Central Italy,

Umbria, and Marche, and about 800 and 500 PLWH, respectively, visited

their Infectious Diseases Clinics.

KS was diagnosed clinically and

histologically, while data about HHV-8 viremia were unavailable for all

the patients due to the study's retrospective nature.

Every

patient provided consent for using his/her data at the hospital

admission. For each one, we collected information about gender, age at

HIV infection diagnosis, nationality, a risk factor for HIV

acquisition, smoking attitude, HHV-8 positivity, HPV positivity, HCV

antibodies positivity, HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) positivity, date of

KS diagnosis and ART starting, CD4 cell count at the moment of HIV

infection and KS diagnosis, viremia at the moment of HIV infection and

KS diagnosis, CD4/CD8 ratio at KS diagnosis, ART regimen, chemotherapy

administered, 5-year survival and eventually the date of death.

CD4

cell count and CD4/CD8 ratio were measured by cytofluorometry, while

HIV RNA was tested by Real-time quantitative PCR, whose detectability

threshold was 20 copies/ml. When HIV RNA was undetectable or under this

threshold, to calculate the median value, we considered HIV viremia 0

or 19, respectively.

HBsAg and HCV antibodies were detected with

chemiluminescent immunoassay, while HPV DNA on anal or cervical swabs

and plasmatic HHV-8 DNA with semi-quantitative PCR.

Due to their

asymmetrical distribution, continuous variables were presented as the

median with IQR, while the categorical ones were expressed by their

relative frequencies. A comparison was performed between patients who

died and those who survived after 5 years from KS diagnosis. The

Mann-Whitney U-test and the Chi-square test were used to compare

differences between groups, as appropriate. A p-value <0.05 was

considered relevant.

Results

In

the considered period, the number of KS cases remained quite stable,

and there was no increase in the post-SARS-CoV2 pandemic time lapse.

Overall, 60 patients were affected by KS: 53 (88.3%) males and 7

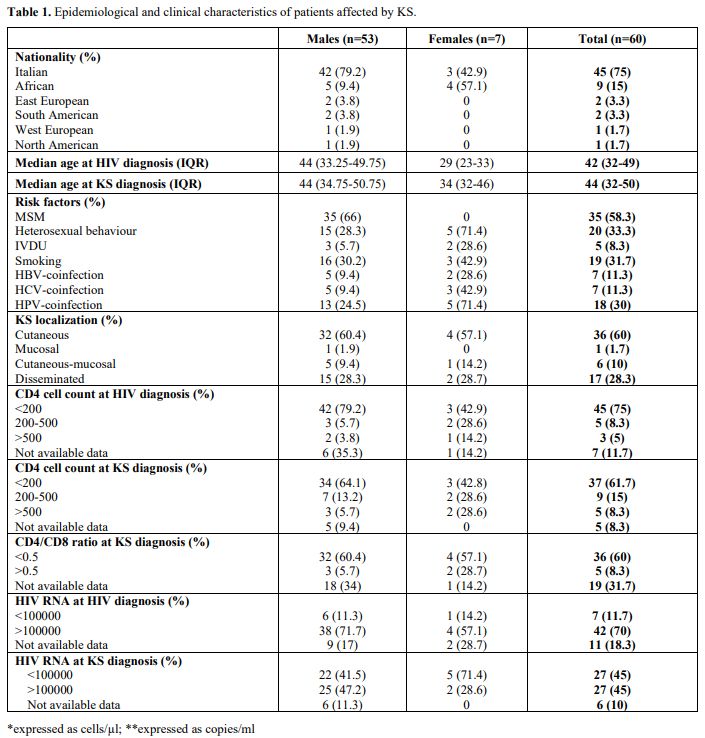

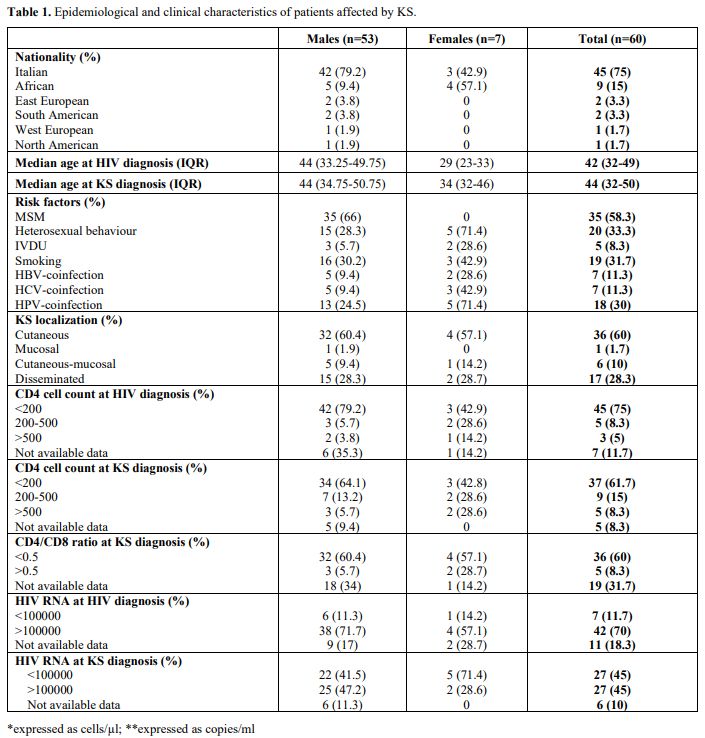

(11.7%) females whose characteristics were summarised in Table 1.

Fourty-5 (75%) were Italians, 9 (15%) were Africans, and 2 (3.3%)

persons were from Eastern Europe, with a median age of 42 and 44 years

at HIV and KS diagnosis, respectively. Some individuals also had other

risk factors for malignancies: 19 (31.7%) smoked, 7 (11.7%), 7 (11.7%),

and 18 (30%) were co-infected with HBV, HCV, and HPV, respectively.

Regarding HIV transmission, 35 (58.3%) were MSM, 20 (33.3%) were

heterosexual people, and 5 (8.3%) were intravenous drug users (IVDU) (Table 1).

|

- Table

1. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of patients affected by KS.

|

At

the moment of HIV infection diagnosis, 42 (70%) persons had HIV RNA

over 100,000 copies/ml (median value: 224,000 copies/ml), 45 (75%), and

47 (78.3%) had CD4+ cell count below 200/µl (median value: 63/µl; IQR

19-135) and 350/µl, respectively. In 38 (63.3%) cases, Kaposi Sarcoma

was the first sign of HIV infection, while in 21 (35%), it manifested

later, and the diagnosis date of a patient was unknown (Table 1).

HHV-8

viremia was available for 20 individuals, and 15 resulted positive,

while histology revealed KS in 6 patients. In 34 cases, both data were

lacking.

KS localized on the skin in 36 (60%) patients, while 1

(1.7%), 6 (10%), and 17 (28.3%) had mucosal, cutaneous-mucosal, and

disseminated forms, respectively. Furthermore, 12 patients were

affected by additional cancerous or precancerous lesions: Castleman

disease (2; 3.3%), primitive effusive Lymphoma (1; 1.7%), cervical (2;

3.3%), and anal intraepithelial neoplasms (1; 1.7%), non-Hodgkin

Lymphoma (1; 1.7%), liver (1; 1.7%), prostate (1; 1.7%) and anal cancer

(3; 5%).

At the moment of KS diagnosis, 37 (61.7%) patients had

CD4 cell count <200/µl (median value: 96 cells/µl), 27 (45%) HIV

viremia >100000 copies/ml (median value: 100000 copies/ml), 36 (60%)

CD4/CD8 <0.5 while 17 (28.3%) were already on ART since a median of

212 days (Table 1).

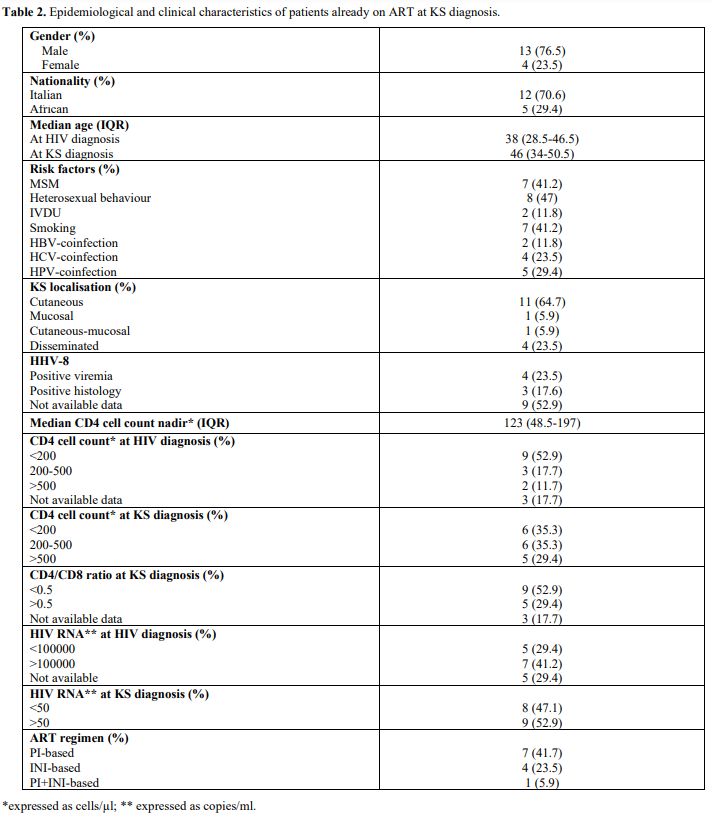

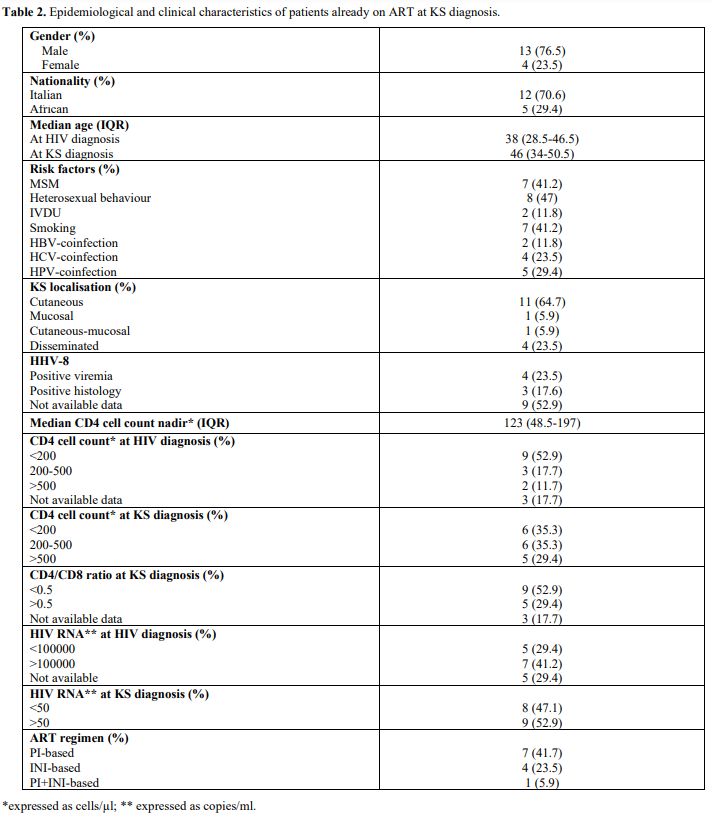

This

special group of people already on treatment included 13 (76.5%) males

with a median CD4 nadir of 123 cells/µl (IQR 48.5-197). Their

epidemiological and clinical data are shown in Table 2.

The median interval from HIV diagnosis to ART starting was 1500 days

(IQR 242.5-4306.5): 7 of them (41.7%) assumed PI-based ART; on the

contrary, 4 (23.5%) the INI-based one.

|

- Table

2. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of patients already on ART at KS diagnosis.

|

Thirty-4

patients (56.7%) were treated only with ART; on the other hand, 18

(30%) needed chemotherapy, 4 (6.6%) radiotherapy, and 3 (5%) surgery.

The prevalent ART regimen was nucleoside reverse transcriptase (NRTI)

and protease (PI) inhibitors (31 cases; 51.7%), followed by NRTI plus

integrase inhibitors (INI) (9 cases; 15%), while 2 (3.3%) patients

received NRTI with both PI and INI (Table 1).

Overall, the median interval between HIV diagnosis and ART start was 17

days (IQR 0.25-57.5), and regimens based on NRTI and INI progressively

increased during the considered period.

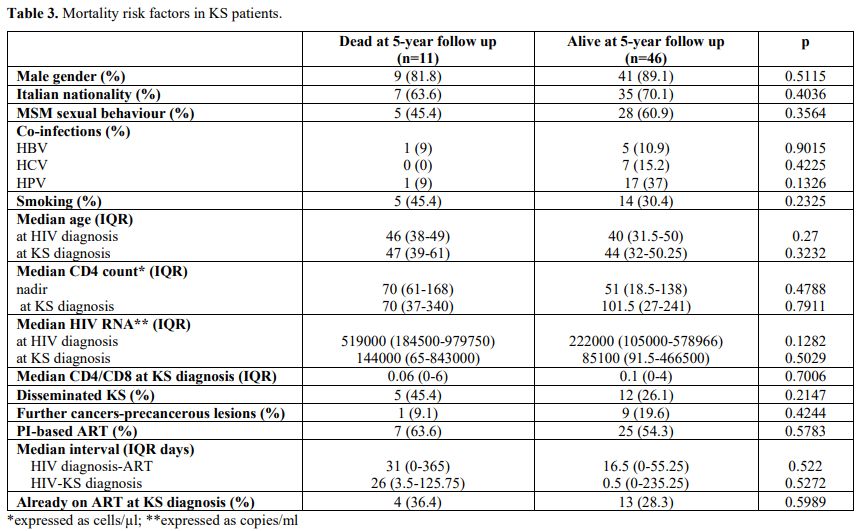

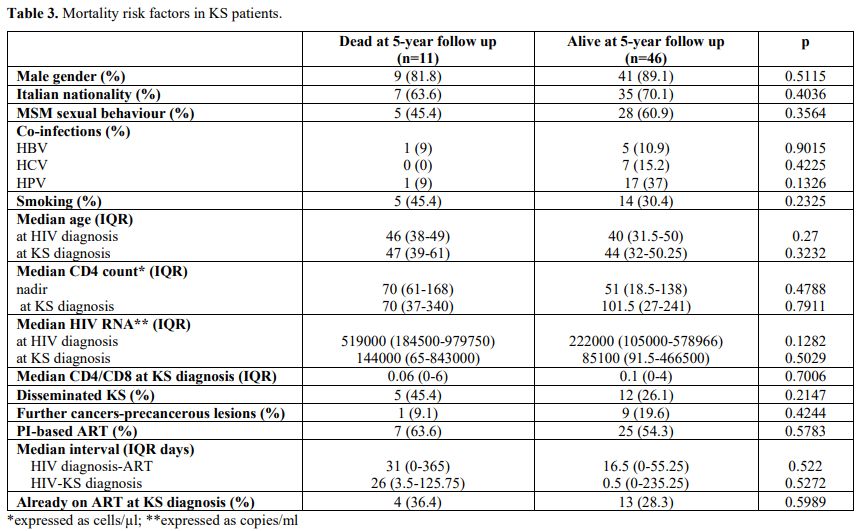

Five years after KS

diagnosis, 46 (76.7%) individuals were still alive: 41 (89.1%) were

male, 28 (60.9%) MSM; 5 (10.9%), 7 (15.2%) and 17 (37%) co-infected by

HBV, HCV, and HPV, respectively; 14 (30.4%) smoked. Their median age

was 40 at HIV diagnosis and 44 at KS diagnosis; 29 (63%) had cutaneous

localization, and 26 (56.5%) were treated only with ART (Table 3).

Univariate analysis did not show any statistically relevant risk factor influencing mortality.

|

- Table 3. Mortality risk factors in KS patients.

|

Discussion

This

study, carried out in 2 Italian hospitals, confirmed that KS is not a

rare disease among PLWH, as shown in the 2020 report, too[1,6,7]

and its frequency has remained constant through the years. Literature

enlightened male gender, homosexual behaviour, and sub-Saharan and

Mediterranean origin being KS risk factors in PLWH [2-5].

Similarly, in our study, males and MSM were the most affected

population groups, while Africans were a minority in our sample. This

distribution reflects the characteristics of patients observed in our

centers, mostly males, Italians, and MSM, as shown in previous

publications.[8-10] The burden of risk factors changes

in different settings; in sub-Saharan Africa, male predominance in KS

is less pronounced, while extremely relevant is a history of sexually

transmitted infections (STIs).[5,11]

Concerning STIs, only 11.7% of our cases were co-infected with HBV and

HCV, and they did not show a higher mortality rate. Also, HPV infection

and smoking regarded just a minority of our population and did not

result to be negative prognostic factors in this analysis.

Unfortunately, too many patients were not tested for HPV and were not

asked about their smoking attitude.

Previously it has been

demonstrated that high viral load, low nadir CD4 count, and CD4/CD8

ratio were associated with KS occurrence.[3,4,12]

More than 70% of our patients had a CD4 count <350 cells/µl either

at HIV or at KS diagnosis, and the median value of CD4 nadir was 63

cells/µl. Similar frequency for viral load and CD4/CD8 ratio. None of

these immunological and viral parameters resulted in enhancing

mortality rate in our sample. Low CD4 cell quantity and high frequency

of concomitant diagnosis of HIV infection and KS confirmed the

increasing number of late HIV diagnoses reported by Istituto Superiore

di Sanità.[13]

Cutaneous and disseminated forms

were the most common in this study, while mucosal ones were localized

in the oral cavity except in 2 cases: 1 in the anus and 1 in the ocular

conjunctive. Rohrmus B et al. reported a higher death rate in oral KS

than in cutaneous KS.[14] Our 5 cases of oral KS are

too few to make the same comparison, and our analysis focused on

disseminated versus not disseminated KS finding no difference in

mortality rate. In addition, 12 KS patients also had other

cancerous or precancerous lesions. In particular, 3 were affected by

other HHV-8-related neoplasms: 2 by Castleman disease and 1 by

primitive effusive Lymphoma. Unfortunately, KS diagnosis was supported

by positive HHV-8 viremia and histology only in 15 and 6 individuals,

respectively. All the 5 persons having negative HHV-8 viremia were

affected by cutaneous KS.

Except for 3 individuals whose data were

unavailable, every patient received ART, and 18, mostly with

disseminated KS, required chemotherapy, too. PI was often included in

the ART regimen according to the evidence of some literature.[15,16] However, there is still debate about this aspect,[17] and also our study failed to prove any benefit of PI-based ART on mortality rate.

Finally,

it is worth noticing that KS diagnosis occurred after HIV diagnosis in

21 patients, and 17 were already on ART when KS was discovered. This

late diagnosis of patients on ART therapy is unsurprising because an

increase of KS incidence in the first 6 months of ART has been

estimated to coincide with the immune reconstitution.[18,19]

In our sample, the 17 patients with a new diagnosis of KS had been on

treatment for about 200 days. This, together with an uncertain

adherence, could explain why, despite therapy, 52.9% of them did not

reach viral suppression at KS diagnosis. Moreover, the main

characteristic of this particular group of PLWH was the longer median

interval between HIV diagnosis and ART starting (1500 versus 17 days)

due to the higher CD4 count (median CD4 nadir 123 versus 63 cells/µl),

and this aspect could represent an additional risk factor for KS.[5]

ART advent and its early starting significantly lowered KS occurrence.[3,4,20] However, our analysis did not show relevant differences in HIV diagnosis-ART starting interval between dead and alive groups.

Limitations

of this study are the small sample size, the number of people lost to

follow-up, and missing data due to the retrospective nature of this

work.

Conclusion

Despite

the ART era, KS is not a rare disease and keeps high lethality.

Individuals examined in our study were mostly Italians, MSM, with high

HIV viral load, low CD4 count and CD4/CD8 ratio. Most of them were

affected by cutaneous KS and treated with PI-based ART. Analyzing

epidemiological and clinical aspects, immune and viral parameters, and

type and timing of ART, we did not find any statistically relevant risk

factor influencing mortality rate. However, the sample size is too

small to generalize these results, and further studies may be needed.

References

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers

in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-49. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660 PMid:33538338

- Martin

JN, Ganem DE, Osmond DH, Page-Shafer KA, Macrae D, Kedes DH. Sexual

Transmission and the Natural History of Human Herpesvirus 8 Infection.

N Engl J Med. 1998;338:948-54. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199804023381403 PMid:9521982

- Poizot-Martin

I, Obry-Roguet V, Duvivier C, Lions C, Huleux T, Jacomet C, Ferry T,

Cheret A, Allavena C, Bani-Sadr F, Palich R, Cabié A, Fresard A,

Pugliese P, Delobel P, Lamaury I, Hustache-Mathieu L, Brégigeon S,

Makinson A, Rey D; Dat'AIDS study group. Kaposi sarcoma among people

living with HIV in the French DAT'AIDS cohort between 2010 and 2015. J

Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(5):1065-73. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.16204 PMid:31953902 PMCid:PMC7318618

- Liu

Z, Fang Q, Zuo J, Minhas V, Wood C, Zhang T. The world-wide incidence

of Kaposi's sarcoma in the HIV/AIDS era. HIV Med. 2018;19(5):355-364.

Epub 2018 Jan 25 https://doi.org/10.1111/hiv.12584 PMid:29368388

- Grabar S, Costagliola D. Epidemiology of Kaposi's Sarcoma. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(22):5692 https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13225692 PMid:34830846 PMCid:PMC8616388

- Ibrahim

Khalil A, Franceschi S, de Martel C, Bray F, Clifford GM. Burden of

Kaposi sarcoma according to HIV status: A systematic review and global

analysis. Int J Cancer. 2022;150(12):1948-57. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.33951 PMid:35085400

- AIDS-defining

Cancer Project Working Group for IeDEA and COHERE in EuroCoord.

Comparison of Kaposi sarcoma risk in human immunodeficiency

virus-positive adults across 5 continents: a multiregional multicohort

study. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65:1316-26.

- Papalini

C, Paciosi F, Schiaroli E, Pierucci S, Busti C, Bozza S, Mencacci A,

Francisci D. Seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV2 Antibodies in Umbrian

Persons Living with HIV. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis.

2020;12(1):e2020080. https://doi.org/10.4084/mjhid.2020.080 PMid:33194154 PMCid:PMC7643777

- Schiaroli

E, De Socio GV, Gabrielli C, Papalini C, Nofri M, Baldelli F, Francisci

D. Partial Achievement of the 90-90-90 UNAIDS Target in a Cohort of HIV

Infected Patients from Central Italy. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis.

2020;12(1):e2020017. https://doi.org/10.4084/mjhid.2020.017 PMid:32180912 PMCid:PMC7059746

- Papalini

C, Lagi F, Schiaroli E, Sterrantino G, Francisci D. Transgender people

living with HIV: characteristics and comparison to homosexual and

heterosexual cisgender patients in two Italian teaching hospitals. Int

J STD AIDS. 2021;32(2):194-198. Epub 2020 Dec 16 https://doi.org/10.1177/0956462420950573 PMid:33327898

- Stolka

K, Ndom P, Hemingway-Foday J, Iriondo-Perez J, Miley W, Labo N, Stella

J, Abassora M, Woelk G, Ryder R, Whitby D, Smith JS. Risk factors for

Kaposi's sarcoma among HIV-positive individuals in a case control study

in Cameroon. Cancer Epidemiol. 2014;38(2):137-43. Epub 2014 Mar 13 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2014.02.006 PMid:24631417 PMCid:PMC4075442

- Caby,

F.; Guiguet, M.; Weiss, L.; Winston, A.; Miro, J.M.; Konopnicki, D.; Le

Moing, V.; Bonnet, F.; Reiss, P.; Mussini, C, Poizot-Martin I, Taylor

N, Skoutelis A, Meyer L, Goujard C, Bartmeyer B, Boesecke C, Antinori

A, Quiros-Roldan E, Wittkop L, Frederiksen C, Castagna A, Thurnheer MC,

Svedhem V, Jose S, Costagliola D, Mary-Krause M, Grabar S; (CD4/CD8

ratio and cancer risk) project Working Group for the Collaboration of

Observational HIV Epidemiological Research Europe (COHERE) in

EuroCoord. CD4/CD8 Ratio and the Risk of Kaposi Sarcoma or Non-Hodgkin

Lymphoma in the Context of Efficiently Treated Human Immunodeficiency

Virus (HIV) Infection: A Collaborative Analysis of 20 European Cohort

Studies. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;73:50-59. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1137 PMid:34370842

- Regine

V, Pugliese L, Boros S, Santaquilani M, Ferri M, Suligoi B.

Aggiornamento delle nuove diagnosi di infezione da HIV e dei casi di

AIDS in Italia al 31 dicembre 2021. Notiziario. 2022;35(11)

- Rohrmus B, Thoma-Greber EM, Rocken M, Bogner JR. Outlook in oral and cutaneous Kaposi's sarcoma. Lancet. 2000;356:2160. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03503-0 PMid:11191549

- Gantt

S, Cattamanchi A, Krantz E, Magaret A, Selke S, Kuntz SR, Huang ML,

Corey L, Wald A, Casper C. Reduced human herpesvirus-8 oropharyngeal

shedding associated with protease inhibitor-based antiretroviral

therapy. J Clin Virol. 2014;60(2):127-32 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2014.03.002 PMid:24698158 PMCid:PMC4020979

- Leitch

H, Trudeau M, Routy JP. Effect of protease inhibitor-based highly

active antiretroviral therapy on survival in HIV-associated advanced

Kaposi's sarcoma patients treated with chemotherapy. HIV Clin Trials.

2003;4:107-14 https://doi.org/10.1310/VQXJ-41X6-GJA2-H6AG PMid:12671778

- Bower

M, Fox P, Fife K, Gill J, Nelson M, Gazzard B. Highly active

antiretroviral therapy (HAART) prolongs time to treatment failure in

Kaposi's sarcoma. AIDS. 1999;13:2105-11 https://doi.org/10.1097/00002030-199910220-00014 PMid:10546864

- Mocroft

A, Kirk O, Clumeck, N, Gargalianos-Kakolyris P, Trocha H, Chentsova N,

Antunes F, Phillips AN, Lundgren J. The changing pattern of Kaposi

sarcoma in patients with HIV, 1994-2003. Cancer. 2004;100:2644-54. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.20309 PMid:15197808

- Cancer

ProjectWorking Group for the Collaboration of Observational HIV

Epidemiological Research Europe Study in EuroCoord. Changing Incidence

and Risk Factors for Kaposi Sarcoma by Time Since Starting

Antiretroviral Therapy: Collaborative Analysis of 21 European Cohort

Studies. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 63, 1373-79. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciw562 PMid:27535953 PMCid:PMC5091347

- Group

I.S.S. Lundgren, JD, Babiker AG, Gordin, F, Emery S, Grund B, Sharma S,

Avihingsanon A, Cooper DA, Fätkenheuer G, Llibre JM, Molina JM, Munderi

P, Schechter M, Wood R, Klingman KL, Collins S, Lane HC, Phillips AN,

Neaton JD. Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy in Early Asymptomatic

HIV Infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:795-807. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1506816 PMid:26192873 PMCid:PMC4569751

[TOP]