Sarah Liptrott1,2,6, Mairéad NíChonghaile3,6, Liz O'Connell4,6 and Erik Aerts5,6.

1 Nursing

Development and Research Unit, Oncology Institute of Southern

Switzerland, Ente Ospedaliero Cantonale (EOC), via Gallino 12, 6500,

Bellinzona, Switzerland.

2 Department of Nursing,

Regional Hospital of Bellinzona e Valli, Ente Ospedaliero Cantonale

(EOC), via Gallino 12, 6500, Bellinzona, Switzerland.

3 HOPE Directorate, St James's Hospital, Dublin 8, Ireland.

4 Haematology Department, Tallaght University Hospital, Dublin 24, Ireland.

5 Department of Internal Medicine, Haematology, University Hospital Zurich, Rämistrasse 100, CH-8091 Zurich, Switzerland.

6 on behalf of the Haematology Nurses and Healthcare Professionals Group (HNHCP).

Correspondence to:

Sarah Liptrott, Nursing Development and Research Unit, Oncology

Institute of Southern Switzerland, Ente Ospedaliero Cantonale (EOC),

via Gallino 12, 6500, Bellinzona, Switzerland; Department of Nursing,

Regional Hospital of Bellinzona e Valli, Ente Ospedaliero Cantonale

(EOC), via Gallino 12, 6500, Bellinzona, Switzerland. Tel:+410918118957

Fax: +410918118056. Email:

sarahjayne.liptrott@eoc.ch

Published: May 1, 2023

Received: March 16, 2023

Accepted: April 20, 2023

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2023, 15(1): e2023033 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2023.033

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Background and Objectives:The

scope of haematology nursing practice is dynamic and must respond to

advances in treatment, patients' needs and service requirements. Little

is known, however, about the different roles of haematology nurses

across the European setting. The purpose of this study was to identify

the professional practices of haematology nurses.

Method:

A cross-sectional online survey design was used to investigate practice

elements undertaken by haematology nurses. Frequencies and descriptive

statistics were calculated for demographic variables and chi-square

tests to examine relationships between practice elements, nursing role

and country.

Results:

Data is reported from 233 nurses across 19 countries, working as Staff

Nurses (52.4%), senior nurses (12.9%) and Advanced Practice Nurses

(APNs) (34.8%). Most frequently reported activities included medication

administration - oral/ intravenous (90.0%), monoclonal antibodies

(83.8%), chemotherapy (80.6%), and blood components (81.4%). APNs were

more commonly involved in nurse-led clinics and prescribing activities

(p < .001, p = .001, respectively); however, other nursing groups

also reported performing extended practice activities. Patient and

carer education was a significant part of all nurses' roles; however,

senior nurses and APNs were more often involved with the

multidisciplinary team (p < .001) and managerial responsibilities (p

< .001). Nurses' involvement in research was limited (36.3%) and

frequently reported as an out-of-work hours activity.

Conclusions:

This study describes haematology nursing care activities performed in

various contexts and within different nursing roles. It provides

further evidence of nursing activity and may contribute to a core

skills framework for haematology nurses.

|

Introduction

Across the WHO European region, there are an estimated 7.3 million nurses and midwives.[1] They are part of progressive healthcare systems responding to the needs of changing and ageing populations,[2] increasingly affected by chronic diseases.[3]

Nurses practice within a context of finite resources, where rising

healthcare costs necessitate effective and efficient service provision.[4]

The scope of nursing practice is dynamic and "describes the

competencies (knowledge, skills and judgement), professional

accountabilities and responsibilities of the nurse";[5]

however, 'nursing practice' is delineated by government legislation and

regulatory authorities, varying between countries, state and even

employing institution.[6,7] In the UK, nurses'

activities at the point of registration have broadened, including an

expected proficiency in ECG performance and interpretation and chest

auscultation.[8] Advanced practice roles have also developed in the USA initially in response to medical staff shortages.[9]

The need for improved access to care and enhanced nurse education has

facilitated their development in different settings and countries.[10]

Policy reforms in some countries have expanded nurses' clinical

practice to incorporate specialisations and activities such as

independent prescribing.[11,12]

While long-term

survival for patients affected by haematological malignancies is

increasing within the haematology setting, late morbidity and mortality

persist,[13] so survivors' healthcare needs to be

addressed. As well as improved survivorship, developments in cancer

nursing have seen several factors contributing to role changes,

including increasing use of immune-based therapies for haematological

malignancies[14] requiring new skills in nursing management, a shift in care delivery from the inpatient to outpatient setting,[15] and increasing numbers of nurse-led clinics.[16]

While literature exists investigating the practice of oncology nurses[17] and those working within advanced practice roles,[11] there is a paucity when exploring haematology nursing practice.

In 2010, Aerts et al.[18]

reported the results of a European survey of 271 nurses across 25

countries. Most common professional activities include patient

education regarding treatment and side effects, monitoring, and

administering supportive care treatment. Differences were also observed

between roles where Clinical Nurse Specialists (CNSs) were more

involved in patient and nurse education and multidisciplinary team

meetings compared to unit-based clinical nurses and Nurse Managers, and

where unit-based clinical nurses were more active in treatment

administration and side-effect management compared to CNSs.

Investigation of the specialist Haemophilia Nurse role in Europe, with

94 respondents from 14 countries, identified four main areas of

practice, treatment (preparation and administration), education and

support (telephone consultation), care coordination and research.[19] Curriculums and competencies for specialist and advanced nursing roles in haematology nursing are available;[20,21]

however, as highlighted earlier, practice application may differ

according to country and institution. Several legislation and nurse

education changes have been reported and implemented since the last

investigation of haematology nurses' practice performed in 2007.[18]

Such developments and the limited knowledge regarding the roles of

nurses working with patients affected by non-malignant haematological

conditions warrant further investigation to map current practice in the

European setting.

The purpose of this study was to identify the

professional practices of haematology nurses and examine whether

differences exist according to role and country of practice.

Methods

Design, Sample and Setting.

We used a cross-sectional survey design. All nurses registered on the

HNHCP Group (Haematology Nurses and Healthcare Professionals Group)

electronic mailing list (2295 individuals) were invited to participate

via email. Researchers were members of the HNHCP Board with access to

the mailing list. The purpose of the survey was explained, and a link

to an online survey (Survey Monkey®, San Mateo, CA, USA) was included.

It was stated that participation was voluntary, and consent was assumed

upon completing the questionnaire. Data collection was anonymous.

Results were available to researchers via password-restricted access.

Questionnaire. Items for the questionnaire were based on the literature about haematology nurses' educational priorities,[22] practice standards and competencies for paediatric non-malignant haematology care[23] and texts relating to advanced nursing practice.[24,25]

The survey questionnaire consisted of 9 subtopics investigating the

demographic details of respondents and asking about the activities

undertaken within their roles such as clinical activities, advanced

practice, education provision (for patients, informal carers and peers/

colleagues), involvement in multidisciplinary team meetings and

decision-making, management responsibilities, involvement in research

and any other areas included in the nurses' role. The questionnaire

also explored perceptions of areas of practice nurses felt should be

included in their role and barriers (including lack of time, skills,

educational opportunities, funding and support) and facilitators

(including protected time, educational courses, funding, managerial

support and medical staff support) to incorporating these into

practice. Resources were reviewed by a research team of four

experienced haematology nurses to agree with the questionnaire content.

The survey was available in the English language.

Statistical analyses.

Descriptive statistics were calculated using the Statistical Package

for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY), and

data were reported as numbers and percentages. The chi-square test was

used for differences between activities undertaken and the nursing

role. Fisher's exact test was used where frequencies were valued at

less than 5. Statistical significance was set at p-values less than

0.05.

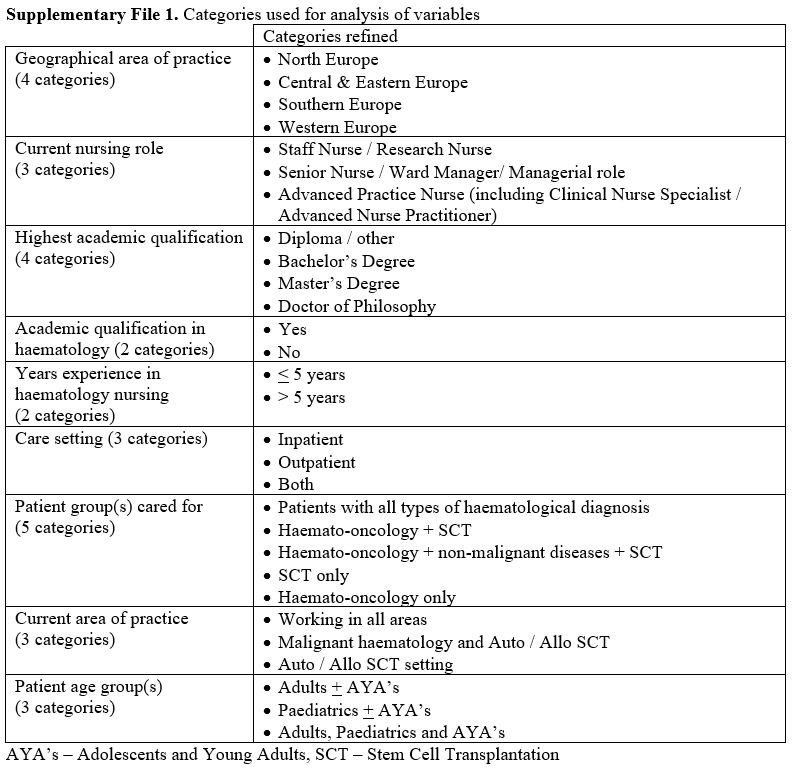

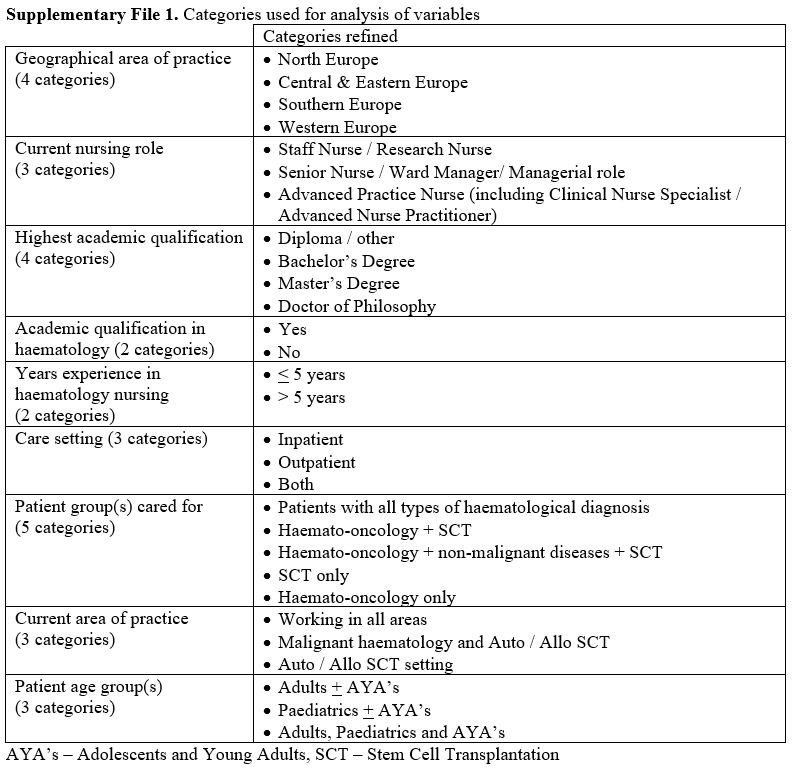

Furthermore, to give an overview of the results, data for

each subtopic has been reduced into categories, e.g. age of respondent,

geographical area of practice, highest academic qualification, patient

group(s) cared for and patient age group(s). Current nursing roles were

grouped according to the role that was predominantly clinically based

(Staff Nurse / Research Nurse), managerial roles (Senior Nurse / Ward

Manager/ Managerial role) or those working at an advanced practice

level (including Clinical Nurse Specialist / Advanced Nurse

Practitioner).

Variables regarding academic qualification in

haematology (completion of a university-recognised course in

haematology), in-house training in haematology (training by local

hospital staff/ employees) and years of experience in haematology

nursing were dichotomised (Supplementary File 1). Qualitative comments collected are summarised within each subtopic.

Results

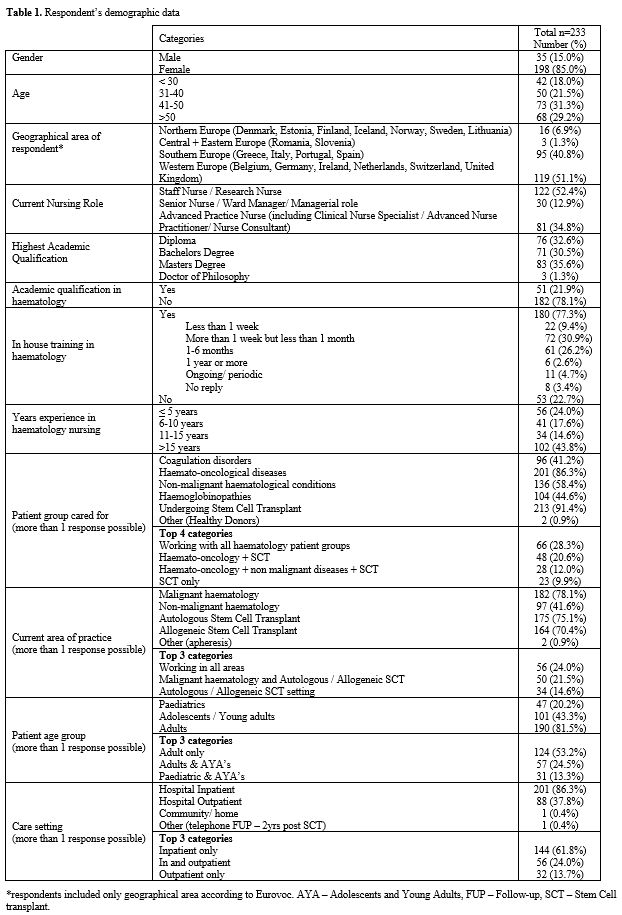

Sample.

Two thousand two hundred ninety-five nurses were invited to respond to

the survey between January and April 2020, and 238 completed responses

were received. Three respondents from non-European countries were

excluded from the analysis (Turkey, Iraq, and Brazil). Two respondents

described their role as nurse researchers and were excluded from the

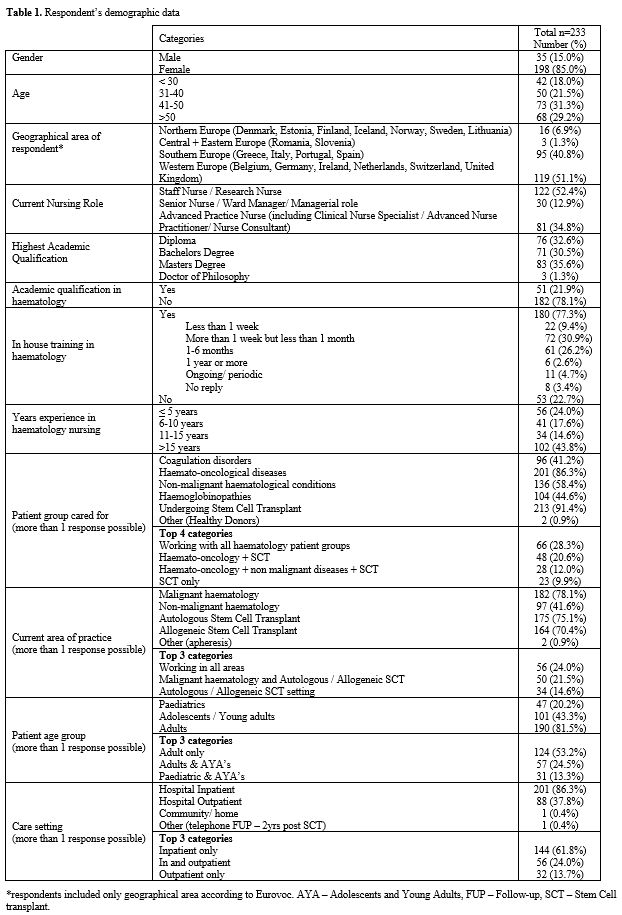

statistical analysis. Table 1

provides a summary of the 233 respondents' characteristics. Respondents

came from 19 countries, principally Western Europe and in particular

Italy, Switzerland and the United Kingdom 82 (35.2%), 47 (20.2%), and

26 (11.2%), respectively. The majority of respondents were female 198

(85.0%), aged 41-50 years of age 73 (31.3%), with the majority working

as Staff Nurses (SN) or Research Nurses (ResN) 122 (52.4%). Over a

third of respondents worked in Advanced Nursing Practice roles, 81

(34.8%), mostly from Western European countries (p = .000). One-third

were in managerial roles, 30 (12.9%).

|

- Table

1. Respondent’s demographic data

|

Most

respondents were educated to Bachelor's degree level or above 157

(67.4%), with over half of Nurse Managers (NMs) and Advanced Practice

Nurses (APNs) educated to Master's degree level (p < .001). Less

than a quarter of nurses had an academic qualification in haematology

51 (21.9%), with the majority of nurses reporting this qualification,

working as APNs (p = .000). In-house training in haematology was more

common across the respondents 180 (77.3%); however, the duration of

in-house training varied, frequently described as being 'more than 1

week but less than 1 month' 72 (30.9%).

Most respondents worked

within haematology for more than 5 years 177 (76.0%). Almost half of

the respondents had worked for more than 15 years in haematology

nursing 102 (43.8%); in particular, these were NMs 18 (60.0%) and APNs

48 (59.3%) (p < .001). The majority of respondents cared for

patients affected by malignant haematological conditions 201 (86.3%) or

non-malignant conditions 136 (58.4%), and nurses caring for patients

with coagulation disorders and hemoglobinopathies were also well

represented 96 (41.2%), and 104 (44.6%). Two respondents cared for

healthy donors and worked in apheresis. Most respondents cared for

patients undergoing Stem Cell Transplant 213 (91.4%), including

autologous Stem Cell Transplant 175 (75.1%) and allogeneic Stem Cell

Transplant 104 (70.4%), and worked in autologous and/or allogeneic stem

cell transplant settings (175, 75.1%; 164, 70.4%, respectively). No

significant differences in the distribution of patients cared for were

seen between nursing role categories.

The majority of nurses

worked with adult patients, only 124 (53.2%), or adult and adolescent/

young adult (AYA) patients, 57 (24.5%). Nurses working with paediatric

and/or AYA patients represented 13.3% (39) of the sample. A greater

proportion of APNs worked with adult patients 49 (60.5%); however, the

finding was not statistically significant.

Inpatient care settings

were the most frequently reported place of work 201 (86.3%), in

particular by SN, ResN and NMs; however, 56 respondents were working

across in- and outpatient settings (24.0%), in particular, APNs 37

(45.7%) (p < .001).

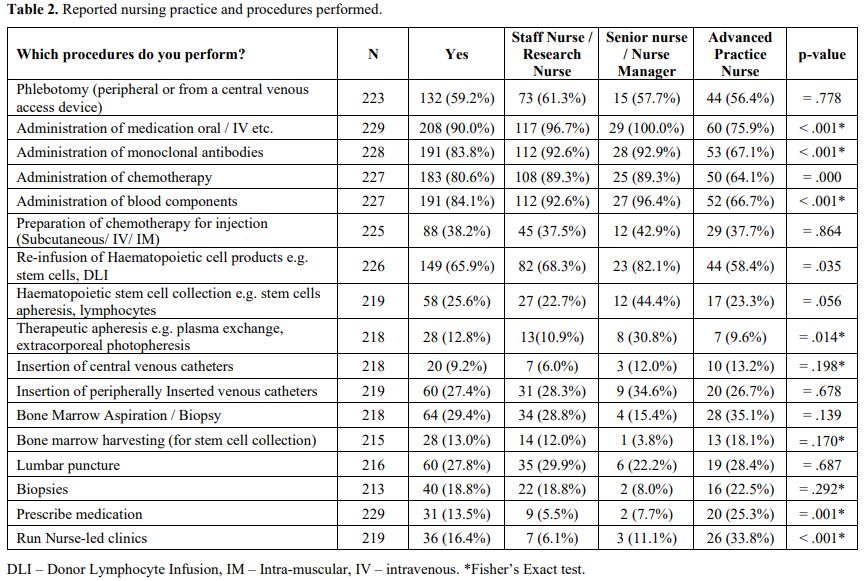

Nursing practice and procedures.

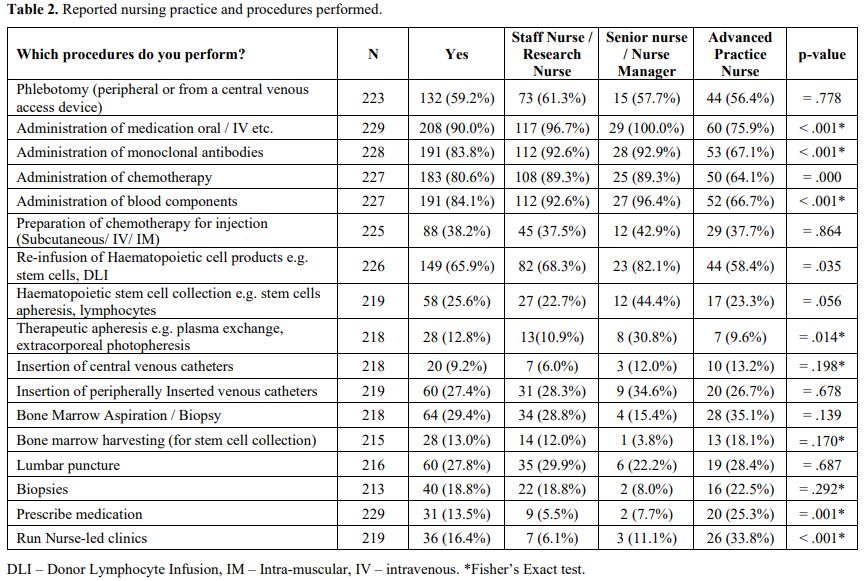

Respondents were asked to identify which activities they performed as

part of their nursing practice. Findings are summarised in Table 2.

Just over half of the sample was used to perform phlebotomy procedures

peripherally or centrally 132 (59.2%). The majority of nurses were

involved in medication administration, including oral and intravenous

(IV) treatments, monoclonal antibodies and chemotherapy 208 (90%), 191

(83.8%), and 183 (80.6%), respectively. Over half of the nurses

reported having received specialist training for drug/ treatment

administration 110 (46.2%), in particular chemotherapy, monoclonal

antibodies and Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cells.

|

- Table

2. Reported nursing practice and procedures performed

|

Over

one-third of nurses reported they prepared chemotherapy for injection

88 (38.2%), the majority being respondents from Italy 36 (43.9% of all

Italian respondents) and Switzerland 17 (36.2% of all Swiss

respondents), and just six (6.8%) of those preparing chemotherapy

reported having received specific training in chemotherapy handling.

Administration of blood components was also common practice 227

(81.4%), with fewer being APNs (p < .001).

Many nurses were

used to performing reinfusion of haematopoietic cell products 149

(65.9%), more so the SN/ ResN group and Senior/ NMs (p = .035). Stem

cell collection and therapeutic apheresis were less common practice

procedures across 58 respondents (25.6%) and 28 (12.8%), respectively,

more commonly performed by Senior/ NMs.

Regarding other advanced

practice procedures, a few nurses were used inserting Central Venous

Catheters (CVCs), 20 (9.2%), primarily APNs. Insertion of Peripherally

Inserted Central Catheters (PICCs) was more common 60 (27.4%), mostly

reported by the SNs / ResN group. Performance of bone marrow

aspiration/biopsy was reported by almost one-third of sample 64 (29.4%)

by both APNs and SNs/ ResN. In comparison, bone marrow harvesting for

stem cell collection was an uncommon procedure in this sample 28

(13.0%) performed by these same nursing groups. Some nurses also

reported performing lumbar punctures 60 (27.8%) and biopsies 40

(18.8%), mainly from Italy and Switzerland. Other activities that

nurses reported included assisting medical staff in performing

procedures such as bone marrow aspiration/ biopsy, harvesting or lumbar

puncture, clinical examination of patients, Chimeric Antigen Receptor

T-cell Therapy coordination, and vaccination.

Thirty-one (13.5%)

nurses reported prescribing medication for their patients, the majority

being from Western European Countries 20 (p = .406) and APNs (p =

.001). Three respondents described prescribing medication for CVCs and

skin problems, while the remaining covered patients with differing

haematological diagnoses, treatment and supportive care areas.

Thirty-six

(16.4%) nurses reported running nurse-led clinics, the majority being

from Western European Countries 26 (p = .007) and APNs (p < .001).

Types of clinics reported were transplant-related (donor care, pre-Stem

Cell Transplant clinics, post allogeneic Stem Cell Transplant,

myelosuppression medication, late effects), supportive care

(transfusion support, medical devices), disease-specific (haemophilia,

immune thrombocytopenia, myeloma, myeloproliferative neoplasms,

leukaemia, lymphoma), non-disease specific (oral therapies, long term

follow up, older patients).

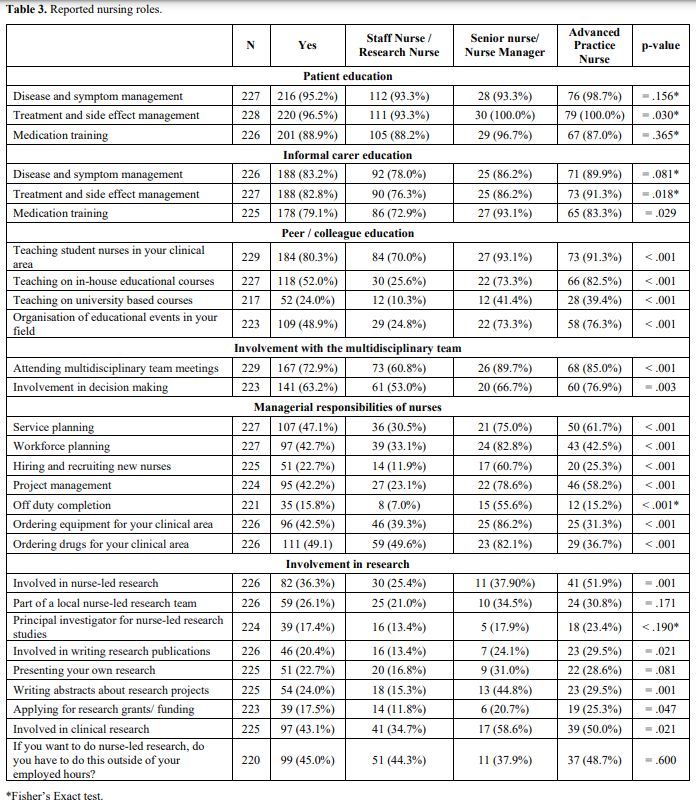

Roles in education.

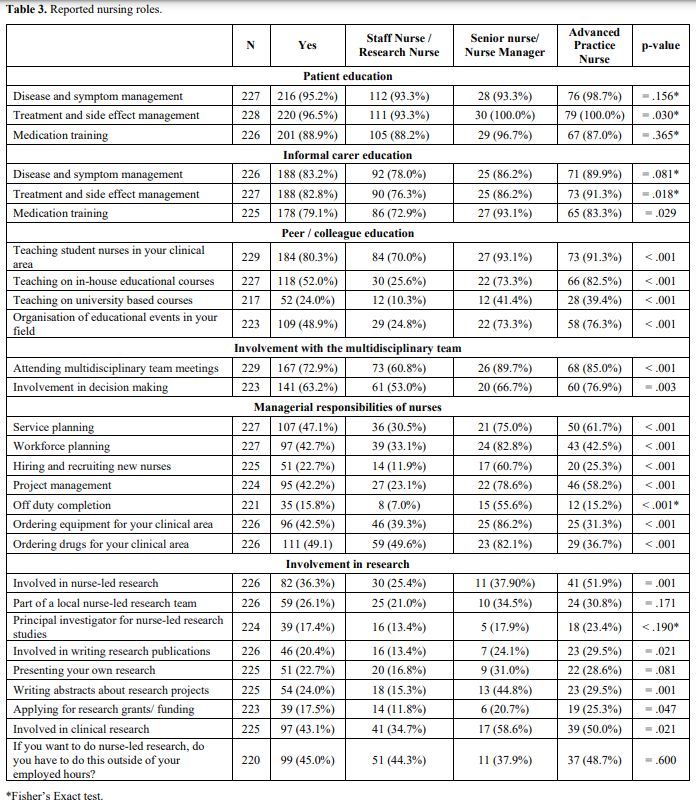

Independent of their role, nurses widely acknowledged their role in

patient education regarding disease and symptom management 216 (95.2%),

treatment and side effect management 220 (96.5%), and medication

training 201 (88.9%) (Table 3).

Other educational examples were Stem Cell Transplant related (the

pathway, self-care after discharge), management of CVCs, and general

topics (nutrition, hygiene and infection prevention, lifestyle

education, sexuality, and coping).

|

- Table 3. Reported nursing roles

|

Education

of informal carers was also seen as a regular part of the nurse's role,

covering disease and symptom management 188 (83.2%), treatment and side

effect management 188 (82.8%), and medication training 178 (79.1%).

Other topics reflected those described above and the performance of

subcutaneous injections.

Peer/colleague education with student

nurses in the clinical area was prevalent 184 (80.3%), mostly reported

by Senior/NMs and APNs. Nurses in these roles were also more frequently

involved in teaching in-house courses, university-based courses and

organising educational events. However, these were overall a less

common role for nurses 118 (52.0%), 52 (24.0%), and 109 (48.9%),

respectively. All findings were statistically significant (p <

.001). Other involvements in education were described, including

education for high schools and patient forums. Overall, nurses

described education to all three groups as a very high/ high priority

within their roles 216 (93.9%), 200 (88.8%), and 200 (88.5%),

respectively.

Role in the Multidisciplinary Team.

The majority of nurses gave a high/ very high priority to involvement

in the multidisciplinary team as part of their role 186 (84.6%), with

many being directly involved in meetings 167 (72.9%), but somewhat

fewer involved in the decision-making process 141 (63.2%) (Table 3). In both cases, these roles were primarily reported by Senior/NMs and APNs (p < .001, p = .003, respectively).

Management responsibilities. Many nurses reported management responsibilities within their roles, not only those in posts of nursing management (Table 3).

Service and workforce planning activities were more common for Senior /

NMs, just one-third of SNs/ ResN reported this as part of their role (p

< .001). Hiring and recruitment primarily comprised Senior/ NMs 17

(60.7%), whereas project management involved APNs. Interestingly, only

35 (15.8%) respondents performed off-duty completion, mostly Senior/

NMs. Ordering drugs and equipment for the clinical area was also a role

reported by this group of nurses, 25 (86.2%) and 23 (82.1%),

respectively.

Research roles. Involvement in nurse-led research was much less frequent as a part of nurses' practice (Table 3).

Over one-third of nurses participated in nurse-led research 82 (36.3%),

the majority being APNs (51.9%) (p = .001). Over a quarter of nurses

said they were part of a local research team 59 (26.1%), but few nurses

were lead investigators for studies 39 (17.4%), a finding similar

across the groups of respondents. Writing and presenting research 51

(22.7%), 54 (24.0%), respectively, and applying for grants and funding

39 (17.5%), were again less common activities more often performed by

Senior/NMs and APN groups. The majority of nurse-led research

activities were reported by respondents from Western and Southern

European countries, although the findings were not statistically

significant. Of greater prevalence was nursing involvement in clinical

research 97 (43.1%).

Almost half of the nurses said that

nurse-led research had to be done outside of employed hours 99 (45.0%),

particularly for Southern European respondents 53 (56.4%) (p = 0.016).

Additional comments highlighted that nurse-led research must be done

within and outside working hours or negotiated in some cases. The

research was given a very high/ high priority by just over half of the

respondents 125 (57.6%), mainly by respondents from Southern European

Countries 72 (77.4%) (p < .001).

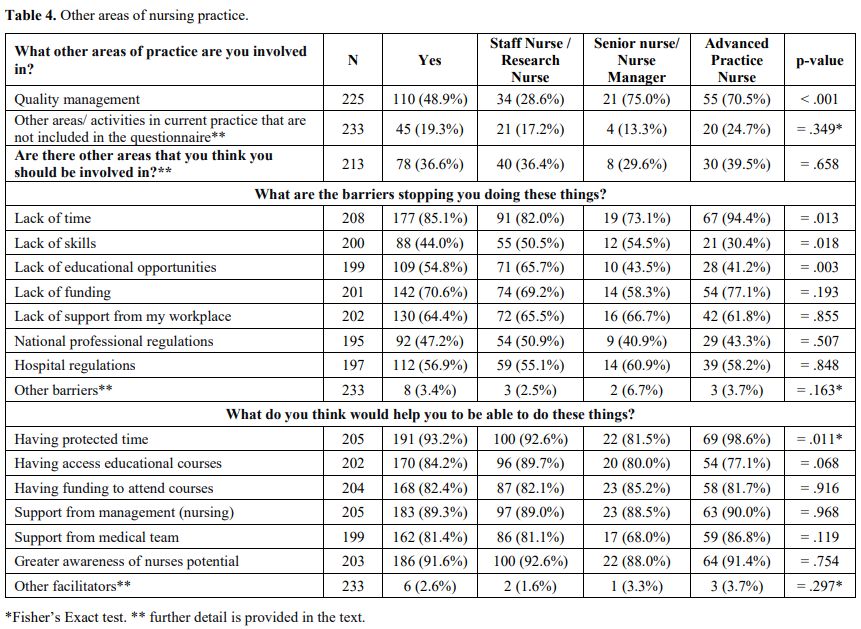

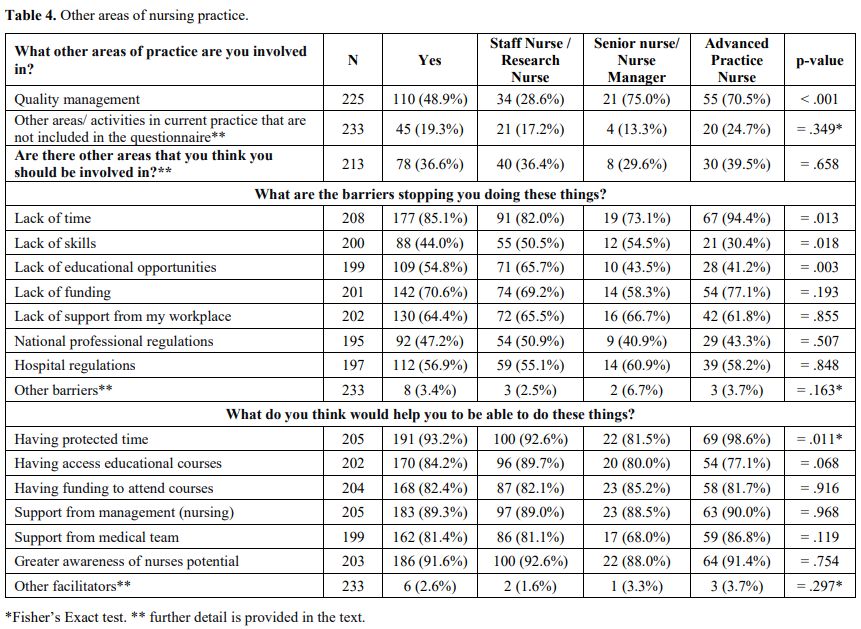

Other areas of practice.

Other areas of current practice reported as being undertaken by

respondents included hospital-wide practice development, quality

management, risk management, data management (completing Stem Cell

Transplant reporting forms), membership of Ethics Committees, and

University professors (Table 4).

One-third of nurses felt that there were other areas they should be

involved in but were not currently part of their practice, including

undertaking advanced practice roles (clinical assessment, prescribing,

nurse-led clinics, case management, virtual and telephone clinics,

performing ultrasound), direct patient care (nutrition, palliative

care, psychological care), nurse-led research and evidence-based

practice (including Stem Cell Transplant), decision making &

multidisciplinary team meeting participation (inc. advanced care

planning), managerial roles (budgeting, planning of medical staff

rotations), education (integrated courses, nurse education), and

involvement with primary care services.

|

- Table 4. Other areas of nursing practice

|

Perceived

barriers to performing these additional roles included lack of time 177

(85.1%), lack of skills 88 (44.0%), lack of education opportunities 109

(54.8%), lack of funding 142 (70.6%), lack of workplace support 130

(64.4%), national professional regulations 92 (47.2%), hospital

regulations 112 (56.9%). Other barriers included poor managerial

support, shift allocation, and lack of administrative support and space.

Respondents

felt that they would be aided in performing these additional roles if

they had protected time 191 (93.2%), access to educational courses 170

(84.2%), funding to attend courses 168 (82.4%), support from nursing

management 183 (89.3%), support from the medical team 162 (81.4%), and

greater awareness of nurses potential 186 (91.6%). Greater

collaboration across haematology departments was also suggested.

.

Discussion

The

study provides greater comprehension of the current clinical and

non-clinical roles of nurses working within the haematology setting

across various countries. While most respondents worked in SN / ResN

roles, extended practice activities and APNs were evident.

Results demonstrated congruence with many activities cited in haematology patient care educational programs;[23] however, there are changes in reported practice compared with a previous survey investigating haematology nurses' role.[18]

Patients

with haematological conditions often undergo blood sampling to evaluate

a range of values, including cell counts, renal and hepatic

functioning, and disease status; however, just over half of the

respondents were involved in blood sampling. This procedure is not part

of the usual activities for many nurses surveyed, and in some

countries, the procedure is often performed by non-nursing personnel.[26]

The

role of nurses in medication management includes a variety of

responsibilities, not only administration but managing therapeutic and

adverse effects, adherence, self-management, education, safety and care

transition.[27] There are continuously emerging therapies for malignant and non-malignant haematological conditions,[28,29] some requiring enhanced knowledge regarding administration techniques, side effect monitoring and management.[30]

Nearly half of the sample reported having specific training for

traditional treatment agents such as chemotherapy and innovative

monoclonal antibody treatments and Chimeric Antigen Receptor -T cell

therapy where treatment side effects include cytokine release and

neurological toxicity and nursing management may be novel.[31]

The preparation of chemotherapy in hospitals and daycare units is a nursing procedure in some centres and countries.[32,33]

While we observed few respondents preparing chemotherapy that reported

having received specific training, it should be noted that European

Parliament has provided legislation regarding the protection of workers

from risks related to exposure to carcinogens,[34,35]

and guidance is available for the safe handling of hazardous drugs for

nurses in oncology emphasising the importance of documented training

and competency.[36]

Transfusion of blood and blood products is part of routine practice due to their life-saving and therapeutic effects[37]

and is commonly performed by nurses; however, infusion of stem cells is

traditionally performed by medical staff or APNs. However, the

literature provides evidence of nurse administration,[38]

as is reported in this sample. A 2007 survey of the haematology nurses'

role highlighted the administration of cytotoxic agents, supportive

care treatments and managing related side effects as activities

performed mostly by unit-based nurses and NMs but also Clinical Nurse

Specialists,[18] reflecting findings in this study.

Apheresis

procedures were less frequently reported aspects of nurses' roles,

particularly senior nurses. This niche nursing field requires specific

training in using an apheresis machine, often in designated units with

Nurse Practitioners and Lead Nurses guiding the team.[39]

While

nurses are frequently involved in the management of venous access

devices, the insertion by nurses of central venous access devices, such

as Peripherally Inserted Central Catheters or Central Venous Catheters,

is traditionally performed by nurses within advanced practice roles;[40] however, in this sample we observed SNs performing this role.

Clinical

procedures often performed within a haematology setting, including bone

marrow aspiration and biopsy, bone marrow harvesting, lumbar puncture

and skin biopsies, are suggested to be competencies within a Nurse

Practitioner role;[21] however, we again observed

reports of SNs performing these procedures which may reflect evidence

of advanced practice without changes within a job title. However, as

many respondents also described how they assisted medical staff with

the procedures, it may be that the question was misinterpreted.

In

2019, nurse prescribing of medicines had been authorised in 13

countries across a range of nursing roles, with educational

requirements varying from being part of nurse education, to those

additional education courses, without necessarily having an APN title.[41] Results from this study reflect this finding, with just over one-third of nurse prescribers not working in APN roles.

A

small proportion of nurses in this sample reported prescribing

medicines in countries where this is not legal, which may reflect

informal prescribing practices.[12]

Nurse-led clinics for patients with haematological disorders have been reported in the literature,[42-44] including APNs running post-disease and treatment survivorship clinics with similar findings in this sample.

Many

of the clinical activities reported by nurses in this survey were not

reported in a previous survey of haematology nursing activities,[18]

which may suggest a trend towards the development of advanced clinical

skills and innovative changes in practice to address service needs.

Education is described as one of the key nursing roles[45] and recognised activity of haematology nurses.[18]

Unsurprisingly this was echoed throughout the respondents in this

sample, providing patient care and peer education. In some countries,

APNs are a standard multidisciplinary team component for patients with

haematological conditions.[46] While involvement in

multidisciplinary team meetings was evident for respondents of all

nursing roles in this study, fewer felt part of the decision-making

process. What can be classed as traditionally managerial roles for

nurses[47] were sometimes reported as being performed

by those outside a managerial role. Possible reasons may include an

approach to prepare future NMs or a redistribution of duties according

to workload.

Nursing research activities were undertaken by just

one-third of respondents, often reporting that this was 'outside

working hours'. Acceptance by managers and facilitation of resources

from both managers and the organisation are attributes of a nursing

research culture;[48] however, few clinical areas can claim to have research positions held by academically trained nurses.[49]

The importance of nursing research to inform evidence-based practice is

fundamental and should be promoted at a European level.

Respondents

in this study highlighted various other areas of practice where they

worked and also areas where they felt they should have a role,

particularly in advanced nursing practice roles, research and

evidence-based practice (EBP), management and education. Many of these

roles require specific competencies and skills, and a lack of skills

and educational opportunities were often cited as barriers to role

development. Attendance at educational conferences is a preferred

method for learning expressed by haematology nurses, allowing

interaction and networking.[22] Of concern is that

these issues impacting role development are more frequently reported

than similar research reported 10 years ago.[18]

Strategies are necessary to ensure that nurses are facilitated in

practice development to meet the complex needs of haematology patients.

The study has identified various clinical and non-clinical

professional practices performed by haematology nurses, with some

differences observed between nursing roles. Evident across all roles

was medication management, ranging from administration to symptom

management, and nurses' key role in patient and caregiver education.

Technical and advanced practice activities, as well as nurse-led

research, were more frequently performed by nurses in APN roles,

whereas both APNs and Senior / NMs had a greater managerial activity.

Although a minority of nurses responded that there were other areas of

practice they felt they should be involved in, no differences were seen

in perceived barriers or facilitators according to the role.

This

survey has provided an important overview of the professional practices

of haematology nurses; however, the study has limitations. The total

number of respondents is small in light of the overall number of nurses

working with haematology patients. As such, these findings cannot be

said to be representative of all nurses or countries. While the study

also aimed to investigate differences according to country of practice,

as two-thirds of the responses were from 3 countries, it was impossible

to make inferences regarding the country. The majority of respondents

worked with patients affected by both malignant and non-malignant

haematological disorders. Therefore, it was impossible to describe the

role of nurses working only with patients affected by non-malignant

haematological conditions. The survey was only available in the English

language, which may have limited completion by some nurses. A

convenience sample was used for the survey, accessed through a

haematology nursing organisation mailing list, aiming to capture

responses from nurses with experience in the speciality. However, it is

recognised that this may bias results towards more experienced nurses

and the tasks and roles reported. Nurses choosing to respond may be

interested in sharing details of their role and activities.

Conclusion

Differences

in haematology nursing practice are observed according to the nursing

roles and some countries' behaviours. The nursing care activities

reported in this article reflect the performance of traditional roles

such as drug administration and education, with developments in the

care of patients affected by haematological conditions, improved

survivorship and ever-evolving therapeutic strategies, requiring

adaptation of nursing care activities to support patients. New

activities reported in nursing practice may reflect new treatment

regimens, task shifting, and regulatory developments. Policy reforms in

some countries now permit expanded nursing roles supported by

supplementary education. All this was evident within the extended

practice roles in the haematology setting, often highlighting

discrepancies between the use of APN titles and activities reported.

These findings can be used to map trends in nursing activity and

contribute to the discussion of a core skills framework for nurses

working within different roles within the haematology setting.

References

- World Health Organization. Data and Statistics. https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/Health-systems/nursing-and-midwifery/data-and-statistics No date. Accessed: 25 May 2021

- Eurostat. Ageing Europe - statistics on population developments. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Ageing_Europe_-_statistics_on_population_developments#:~:text=The%20population%20of%20older%20people,reach%20129.8%20million%20by%202050 2020. Accessed: 25 May 2021

- Busse

R, Blümel M, Scheller-Kreinsen D, Zenter A. Tackling Chronic Disease In

Europe: Strategies, interventions and challenges. Observatory Studies

Series No 20. World Health Organization, on behalf of the European

Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, UK. 2020.

- Organisation

for Economic Cooperation and Development. Caring for Quality in Health:

Lessons Learnt from 15 Reviews of Health Care Quality, OECD Reviews of

Health Care Quality, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264267787-en 2017. Accessed: 20 May 2021

- International Council of Nurses. Scope of Nursing Practice: Position Statement. https://www.icn.ch/sites/default/files/inline-files/B07_Scope_Nsg_Practice.pdf 2013. Accessed: 25 May 2021

- Mackey

H, Noonan K, Kennedy Sheldon L, Singer M, Turner T. Oncology Nurse

Practitioner Role: Recommendations From the Oncology Nursing Society's

Nurse Practitioner Summit. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2018 Oct 1;22(5):516-522.

doi: 10.1188/18.CJON.516-522. https://doi.org/10.1188/18.CJON.516-522 PMid:30239518

- Park

J, Athey E, Pericak A, Pulcini J, Greene J. To What Extent Are State

Scope of Practice Laws Related to Nurse Practitioners' Day-to-Day

Practice Autonomy? Med Care Res Rev. 2018 Feb;75(1):66-87. doi:

10.1177/1077558716677826. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558716677826 PMid:29148318

- Nursing

and Midwifery Council. Future nurse: standards of proficiency for

registered nurses.

https://www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/education-standards/future-nurse-proficiencies.pdf

2018. Accessed: 27 May 2021

- Wilson D. Nurse Practitioners: The Early Years (1965-1974). Maine Nurse Practitioner Association, Maine. 2003.

- Sheer

B, Wong FK. The development of advanced nursing practice globally. J

Nurs Scholarsh. 2008;40(3):204-11. doi:

10.1111/j.1547-5069.2008.00242.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2008.00242.x PMid:18840202

- Kelly

D, Lankshear A, Wiseman T, Jahn P, Mall-Roosmäe H, Rannus K,

Oldenmenger W, Sharp L. The experiences of cancer nurses working in

four European countries: A qualitative study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2020

Dec;49:101844. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2020.101844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2020.101844 PMid:33166924 PMCid:PMC7556264

- Maier

CB, Köppen J, Busse R; MUNROS team. Task shifting between physicians

and nurses in acute care hospitals: cross-sectional study in nine

countries. Hum Resour Health. 2018 May 25;16(1):24. doi:

10.1186/s12960-018-0285-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-018-0285-9 PMid:29801452 PMCid:PMC5970499

- Pulte

D, Jansen L, Brenner H. Changes in long term survival after diagnosis

with common hematologic malignancies in the early 21st century. Blood

Cancer J. 2020 May 13;10(5):56. doi: 10.1038/s41408-020-0323-4. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-020-0323-4 PMid:32404891 PMCid:PMC7221083

- Einsele

H, Briones J, Ciceri F, García-Cadenas I, Falkenburg F, Bolaños N,

Heemskerk HMM, Houot R, Hudecek M, Locatelli F, Morgan K, Morris CE,

O'Dwyer M, Gil JS, van den Brink M, van de Loosdrecht AA. Immune-based

Therapies for Hematological Malignancies: An Update by the EHA SWG on

Immunotherapy of Hematological Malignancies. Hemasphere. 2020 Jun

29;4(4):e423. doi: 10.1097/HS9.0000000000000423. https://doi.org/10.1097/HS9.0000000000000423 PMid:32904089 PMCid:PMC7448369

- Bertucci

F, Le Corroller-Soriano AG, Monneur-Miramon A, Moulin JF, Fluzin S,

Maraninchi D, Gonçalves A. Outpatient Cancer Care Delivery in the

Context of E-Oncology: A French Perspective on "Cancer outside the

Hospital Walls". Cancers (Basel). 2019 Feb 14;11(2):219. doi:

10.3390/cancers11020219. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11020219 PMid:30769858 PMCid:PMC6406853

- Farrell

C, Walshe C, Molassiotis A. Are nurse-led chemotherapy clinics really

nurse-led? An ethnographic study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2017 Apr;69:1-8.

doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.01.005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.01.005 PMid:28113082

- Lemonde

M, Payman N. Perceived roles of oncology nursing. Can Oncol Nurs J.

2015 Fall;25(4):422-42. doi: 10.5737/23688076254422431. https://doi.org/10.5737/23688076254422431 PMid:26897865

- Aerts

E, Fliedner M, Redmond K, Walton A. Defining the scope of haematology

nursing practice in Europe. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2010 Feb;14(1):55-60.

doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2009.06.008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2009.06.008 PMid:19734088

- Schrijvers

L, Bedford M, Elfvinge P, Andritschke K, Leenders B, Harrington C. The

role of the European haemophilia nurse. J Haem Pract. 2013. 1(1):24-7.

doi: 10.17225/jhp.00008 https://doi.org/10.17225/jhp.00008

- EAHAD

Nurses Committee; Harrington C, Bedford M, Andritschke K, Barrie A,

Elfvinge P, Grønhaug S, Mueller-Kagi E, Leenders B, Schrijvers LH. A

European curriculum for nurses working in haemophilia. Haemophilia.

2016 Jan;22(1):103-9. doi: 10.1111/hae.12785. https://doi.org/10.1111/hae.12785 PMid:26278710

- Knopf

KE. Core competencies for bone marrow transplantation nurse

practitioners. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2011 Feb;15(1):102-5. doi:

10.1188/11.CJON.102-105 https://doi.org/10.1188/11.CJON.102-105 PMid:21278047

- Liptrott

S, NíChonghaile M, Aerts E; Haematology Nurses and Healthcare

Professionals Group (HNHCP). Investigating the self-perceived

educational priorities of haematology nurses. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2019

Aug;41:72-81. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2019.05.010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2019.05.010 PMid:31358261

- Atlantic

Provinces Pediatric Hematology Oncology Network (APPHON)/ Réseau

d'Oncologie et Hématologie Pédiatrique des Provinces Atlantiques

(ROHPPA). Practice Standards and Competencies for Nurses Providing

Pediatric Non Malignant Hematology Care in Atlantic Canada https://www.apphon-rohppa.com/en/system/files/u5/Final.hem_nursing.practice_standards_and_competencies.July%202008.pdf 2008. Accessed: 20 October 2019

- Bruinooge

SS, Pickard TA, Vogel W, Hanley A, Schenkel C, Garrett-Mayer E,

Tetzlaff E, Rosenzweig M, Hylton H, Westin SN, Smith N, Lynch C, Kosty

MP, Williams SF. Understanding the Role of Advanced Practice Providers

in Oncology in the United States. J Oncol Pract. 2018

Sep;14(9):e518-e532. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00181. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.18.00181 PMid:30133346

- Canadian Nursing Association. Advanced Practice Nursing: a Pan-Canadia Framework. https://www.cna-aiic.ca/-/media/cna/page-content/pdf-en/advanced-practice-nursing-framework-en.pdf?la=en&hash=76A98ADEE62E655E158026DEB45326C8C9528B1B 2019. Accessed: 15 October 2019

- Simundic

A. Who is Doing Phlebotomy in Europe?. In: Guder W, Narayanan S, eds.

Pre-Examination Procedures in Laboratory Diagnostics: Preanalytical

Aspects and their Impact on the Quality of Medical Laboratory Results.

Berlin, München, Boston: De Gruyter, 2015; 90-94. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110334043-015

- De

Baetselier E, Dilles T, Feyen H, Haegdorens F, Mortelmans L, Van

Rompaey B. Nurses' responsibilities and tasks in pharmaceutical care: A

scoping review. Nurs Open. 2022 Nov;9(6):2562-2571. doi:

10.1002/nop2.984. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.984 PMid:34268910 PMCid:PMC9584497

- Hou

JZ, Ye JC, Pu JJ, Liu H, Ding W, Zheng H, Liu D. Novel agents and

regimens for hematological malignancies: recent updates from 2020 ASH

annual meeting. J Hematol Oncol. 2021 Apr 21;14(1):66. doi:

10.1186/s13045-021-01077-3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-021-01077-3 PMid:33879198 PMCid:PMC8059303

- Neumayr

LD, Hoppe CC, Brown C. Sickle cell disease: current treatment and

emerging therapies. Am J Manag Care. 2019 Nov;25(18 Suppl):S335-S343.

- Szoch

S, Boord C, Duffy A, Patzke C. Addressing Administration Challenges

Associated With Blinatumomab Infusions: A Multidisciplinary Approach. J

Infus Nurs. 2018 Jul/Aug;41(4):241-246. doi:

10.1097/NAN.0000000000000283. https://doi.org/10.1097/NAN.0000000000000283 PMid:29958260

- Beaupierre

A, Kahle N, Lundberg R, Patterson A. Educating Multidisciplinary Care

Teams, Patients, and Caregivers on CAR T-Cell Therapy. J Adv Pract

Oncol. 2019 May-Jun;10(Suppl 3):29-40. doi:

10.6004/jadpro.2019.10.4.12. https://doi.org/10.6004/jadpro.2019.10.4.12 PMid:33520344 PMCid:PMC7521122

- Koulounti

M, Roupa Z, Charalambous C, Noula M. Assessment of Nurse's Safe

Behavior Towards Chemotherapy Management. Mater Sociomed. 2019

Dec;31(4):282-285. doi: 10.5455/msm.2019.31.282-285. https://doi.org/10.5455/msm.2019.31.282-285 PMid:32082094 PMCid:PMC7007613

- Ulas

A, Silay K, Akinci S, Dede DS, Akinci MB, Sendur MA, Cubukcu E, Coskun

HS, Degirmenci M, Utkan G, Ozdemir N, Isikdogan A, Buyukcelik A, Inanc

M, Bilici A, Odabasi H, Cihan S, Avci N, Yalcin B. Medication errors in

chemotherapy preparation and administration: a survey conducted among

oncology nurses in Turkey. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev.

2015;16(5):1699-705. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.5.1699. https://doi.org/10.7314/APJCP.2015.16.5.1699 PMid:25773812

- Directive

(EU) 2022/431 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 9 March

2022 amending Directive 2004/37/EC on the protection of workers from

the risks related to exposure to carcinogens or mutagens at work. 2022.

Official Journal L88/1. http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2022/431/oj Accessed: 12 Mar 2023

- Directive

2004/37/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April

2004 on the protection of workers from the risks related to exposure to

carcinogens or mutagens at work (Sixth individual Directive within the

meaning of Article 16(1) of Council Directive 89/391/EEC) (codified

version) (Text with EEA relevance). 2004. Official Journal L158/50. http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2004/37/oj Accessed: 12 Mar 2023.

- Oncology Nursing Society. Toolkit for Safe Handling of Hazardous Drugs for Nurses in Oncology. https://www.ons.org/sites/default/files/2018-06/ONS_Safe_Handling_Toolkit_0.pdf 2018. Accessed: 25 May 2021

- World Health Organization. 2020, Blood Transfusion. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, https://www.who.int/news-room/facts-in-pictures/detail/blood-transfusion 2020. Accessed: 10 February 2021

- de

Vera MR, Malick L. Stem Cell Infusion: Changing Practice Through

Education and Collaboration. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018; 24(3):

S473-S474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.12.753

- Wilson

S, Chauhan A, Morris C, Manton A. Therapeutic apheresis services: a

unique field of nursing within NHSBT. Br J Nurs. 2020 Jun

11;29(11):639-641. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2020.29.11.639. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2020.29.11.639 PMid:32516039

- Ostrowski

AM, Morrison S, O'Donnell J. Development of a Training Program in

Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter Placement for Certified

Registered Nurse Anesthetists Using an N-of-1 Method. AANA J. 2019

Feb;87(1):11-18.

- Maier

CB. Nurse prescribing of medicines in 13 European countries. Hum Resour

Health. 2019 Dec 9;17(1):95. doi: 10.1186/s12960-019-0429-6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-019-0429-6 PMid:31815622 PMCid:PMC6902591

- Overend

A, Khoo K, Delorme M, Krause V, Avanessian A, Saltman D. Evaluation of

a nurse-led telephone follow-up clinic for patients with indolent and

chronic hematological malignancies: a pilot study. Can Oncol Nurs J.

2008 Spring;18(2):64-73. English, French. doi: 10.5737/1181912x1826468.

https://doi.org/10.5737/1181912x1826468 PMid:18649698

- Taylor

K, Chivers P, Bulsara C, Joske D, Bulsara M, Monterosso L. Care After

Lymphoma (CALy) trial: A phase II pilot pragmatic randomised controlled

trial of a nurse-led model of survivorship care. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2019

Jun;40:53-62. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2019.03.005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2019.03.005 PMid:31229207

- Thompson

R, Tonkin J, Francis Y, Pattinson A, Peters T, Taylor M, Wallis L.

Nurse-led clinics for haematological disorders. Cancer Nursing

Practice. 2012. 11(10): 14-20. doi: 10.7748/cnp2012.12.11.10.14.c9472 https://doi.org/10.7748/cnp2012.12.11.10.14.c9472

- International Council of Nurses. The ICN definition of nursing. https://www.icn.ch/nursing-policy/nursing-definitions. 2002. Accessed: 25 May 2021

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Haematological cancers: improving outcomes. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng47 2016. Accessed: 25 May 2021

- American Organization of Nurse Executives. Nurse Manager Competencies. https://www.aonl.org/system/files/medi/file/2019/04/ nurse-manager-competencies.pdf. 2015. Accessed: 12 October 2021

- Berthelsen

CB, Hølge-Hazelton B. 'Nursing research culture' in the context of

clinical nursing practice: addressing a conceptual problem. J Adv Nurs.

2017 May;73(5):1066-1074. doi: 10.1111/jan.13229. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13229 PMid:27906467

- Hølge-Hazelton

B, Kjerholt M, Berthelsen CB, Thomsen TG. Integrating nurse researchers

in clinical practice - a challenging, but necessary task for nurse

leaders. J Nurs Manag. 2016 May;24(4):465-74. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12345. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12345 PMid:26667268

Supplementary File 1

|

- Supplementary File 1. Categories used for analysis of variables.y setting.

|

[TOP]