Daniele Avenoso, Amal

Alabdulwahab, Michelle Kenyon, Varun Mehra, Pramila Krishnamurthy,

Francesco Dazzi, Ye Ting Leung, Sandra Anteh, Mili Naresh Shah, Andrea

Kuhnl, Robin Sanderson, Piers Patten, Deborah Yallop, Antonio Pagliuca

and Victoria Potter.

King's College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Department of Haematological medicine, Denmark Hill, London.

Correspondence to: Dr

Daniele Avenoso, King's College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust,

Department of Haematological medicine, Denmark Hill, London. E-mail:

d.avenoso@nhs.net

Published: July 1, 2023

Received: March 19, 2023

Accepted: June 18, 2023

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2023, 15(1): e2023041 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2023.041

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Background: The

second decade of this millennium was characterized by a widespread

availability of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapies to

treat relapsed and refractory lymphomas. As expected, the role and

indication of allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplant

(allo-HSCT) in the management of lymphoma changed. Currently, a

non-neglectable proportion of patients will be considered candidate for

an allo-HSCT, and the debate of which transplant platform should be

offered is still active.

Objectives: To

report the outcome of patients affected with relapsed/refractory

lymphoma and transplanted following reduced intensity conditioning at

King's College Hospital, London, between January 2009 and April 2021.

Methods: Conditioning was with 150mg/m2 of fludarabine and melphalan of 140mg/m2.

The graft was unmanipulated G-CSF mobilized peripheral blood

haematopoietic stem cells (PBSC). Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD)

prophylaxis consisted of pre-transplant Campath at the total dose of 60

mg in unrelated donors and 30 mg in fully matched sibling donors and

ciclosporin.

Results: One-year

and five years OS were 87% and 79.9%, respectively, and median OS was

not reached. The cumulative incidence of relapse was 16%. The incidence

of acute GVHD was 48% (only grade I/II); no cases of grade III/IV were

diagnosed. Chronic GVHD occurred in 39% of patients. TRM was 12%, with

no cases developed within day 100 and 18 months after the procedure.

Conclusions: The

outcomes of heavily pretreated lymphoma patients are favorable, with

median OS and survival not reached after a median of 49 months. In

conclusion, even if some lymphoma subgroups cannot be treated (yet)

with advanced cellular therapies, this study confirms the role of

allo-HSCT as a safe and curative strategy.

|

Introduction

The

second decade of this millennium was characterized by the widespread

availability of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapies to

treat relapsed and refractory lymphomas, changing these entities'

prognosis and treatment landscape.[1-5]

Also, the

development of antibody-conjugated therapies or bi-specific antibodies

further enriched the treatment algorithm creating more therapeutic

dilemmas in selecting the most effective and safe therapy after the

second relapse and beyond.[6,7]

As expected, the

role and indication of allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplant

(allo-HSCT) in the management of lymphoma changed, and it is currently

redefining its role in the treatment pathway of our patients.

Interestingly, the first decade of the millennium can be remembered with a global effort in proving a graft-versus-lymphoma effect and in identifying the safest conditioning regimens before the infusion of the graft.[8]

Different groups previously showed that reduced intensity conditioning

(RIC) regimens could offer the engraftment of the donor immune system

without exposing the patients to an unacceptable risk of

transplant-related mortality (TRM).[9,10,11]

Despite

the new treatment options mentioned before, a not neglectable

proportion of patients, due to the lack of CAR-T products or any other

modern therapy, will be considered a candidate for an allo-HSCT.[12] Therefore, the debate of which transplant platform/conditioning regimen should be offered is still active.

Herein

we report the outcome of patients affected with relapsed/refractory

lymphoma and transplanted following RIC administration.

Material and Methods

Conditioning was administered with 150 mg/m2 of fludarabine and melphalan of 140 mg/m2.

Graft-versus-host

disease (GVHD) prophylaxis consisted of pre-transplant Campath at the

total dose of 60 mg in unrelated donors and 30 mg in fully matched

sibling donors, and ciclosporin 3 mg/Kg from day -1 (therapeutic level

of 150-200) until d+56 and then tapered in the absence of GVHD aiming

to stop it on day +90.

|

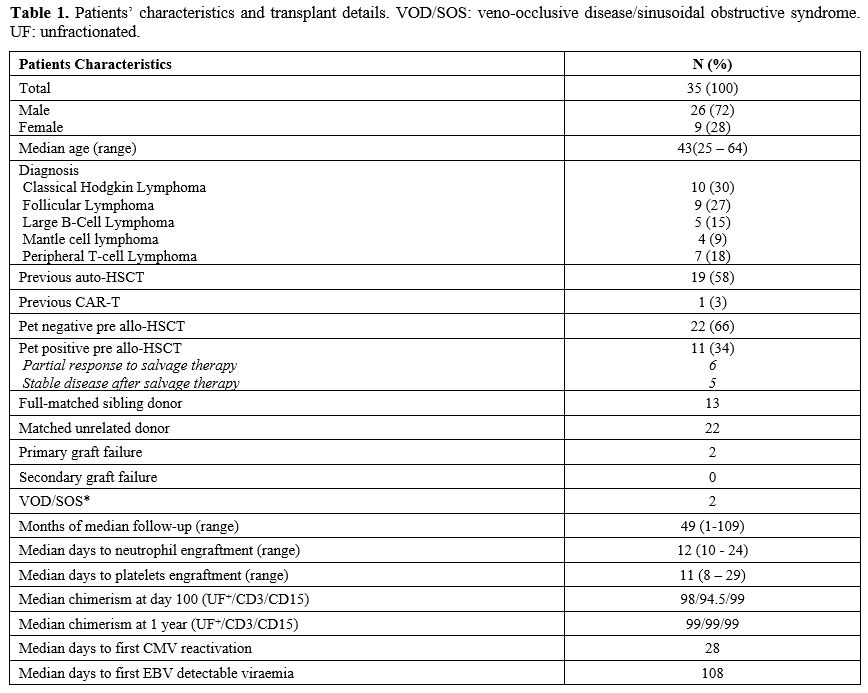

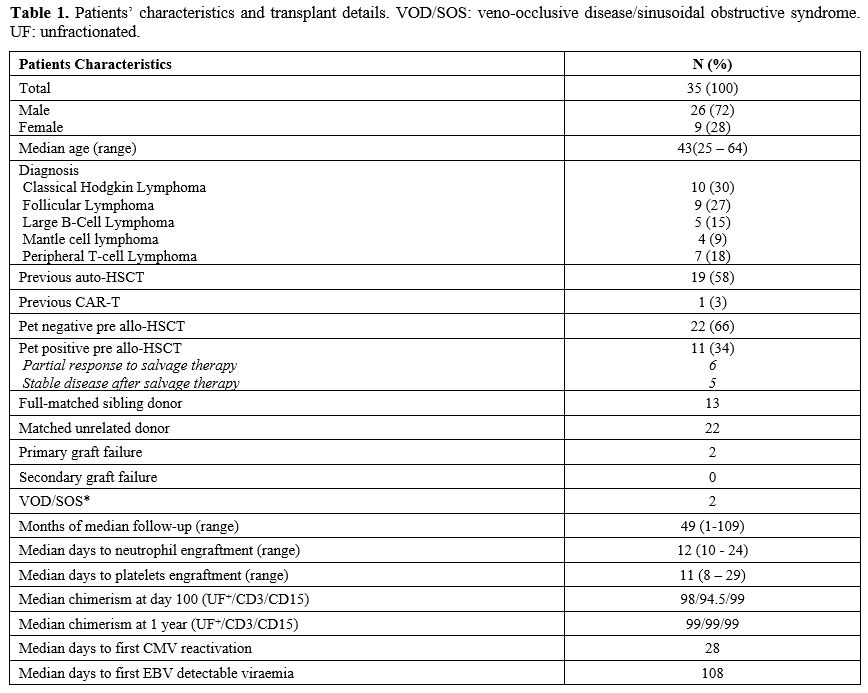

- Table

1. Patients' characteristics and transplant details. VOD/SOS:

veno-occlusive disease/sinusoidal obstructive syndrome. UF:

unfractionated.

|

Between

January 2012 and April 2022, 35 patients (9 females and 26 males)

affected with different lymphoma subtypes underwent allo-HSCT at King's

College Hospital in London, United Kingdom. Table 1 summarizes the patients' characteristics and shows the transplant details. Median follow-up was 49 months (range 1-109).

Donors

and recipients were typed using Third Generation Sequencing (TGS) and

Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) techniques for HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1,

-DQ at a high-resolution level. Donors were considered mismatched if

<10/10 match was present.

Probabilities of overall survival

(OS) and GVHD-relapse-free survival (GRFS) were calculated using the

Kaplan-Meier method. Relapse incidence (RI) and transplant-related

mortality (TRM) rates were estimated using cumulative incidence (CI)

functions and considered as competing risks. For GvHD, death and

relapse were considered competing events. Univariate analyses were

performed using the log-rank test for OS, GRFS, and Gray's test for RI

and TRM. Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism

Version 9.4.1.

Results

The graft was unmanipulated G-CSF mobilized peripheral blood haematopoietic stem cells PBSC). A median of 7x106 CD34+/Kg was infused (range 1.8 – 11.2). Median time to neutrophils ≥ 1000/μL was 12 days (10-24), and 11 days (8-29) to platelets ≥ 20.000/μL;

no deaths before engraftment were recorded. Two cases of primary graft

failure occurred; despite autologous reconstitution, these patients

achieved complete remission (CR).

Median unfractionated, CD3+, and CD15 chimerism at 365 days after transplant were 99% and 99%, respectively.

One-year and five years OS were 87% and 79.9%, respectively, and median OS was not reached.

One-year and five years GFRS were 69% and 61%, respectively, with median GRFS not reached (Figure 1A).

The global CI of relapse was 16%, with no late relapses seen beyond 24 months after transplant (Figure 1B);

it is worth highlighting that one of the relapsed patients achieved

durable complete remission following the withdrawal of immune

suppressive therapy, and two patients following the infusion of donor

lymphocyte infusions (DLI).

The overall incidence of acute GVHD

was 48% (15 patients were affected with grade I, and only one patient

had grade II); no grade III/IV cases were diagnosed. The median time to

acute GVHD was 57 days (range 23-112). Chronic GVHD occurred in 39% of

patients; within this group, moderate and severe cases were noted in 4

and 3 patients, respectively. The median time to chronic GVHD was 171

days (range 107-511).

Overall TRM was 12%, with no cases developed within day 100 and 18 months after the procedure (Figure 1C). The leading causes of death were infections (3 cases) and disease progression (1).

CMV

reactivation occurred in 41% with a median time to first CMV

reactivation of 28 days (range -6 – 251). No CMV disease occurred, and

all the patients received pre-emptive therapy per local policy.

EBV-detectable

viraemia occurred in 51% of the patients at a median time of 108 days

(range 22 – 713); two monomorphic PTLD cases required treatment with

rituximab achieving CR.

Disease status at the time of transplant

has an impact on OS: patients in complete remission at the time of

transplant had a five years OS of 80% compared to 65% in those with a

partial response at the time of transplant (Figure 1D);

an analogous situation for those who underwent up-front allo-HSCT.

These results confirm that chemo-sensitive disease can benefit from

allo-HSCT even in partial response.

From a histological point of

view, non-large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL) had a better outcome, with

median OS never reached compared to LBCL (Figure 1E).

It is worth highlighting that the two LBCL patients that failed HSCT

underwent the procedure with detectable disease at the PET scan before

transplant, suggesting that high proliferative tumour burden cannot be

controlled with the GVL effect.[13]

|

- Figure 1. (A) Overall survival (OS) and GVHD-Relapse free survival (GRFS) of the whole cohort. (B) Cumulative incidence of relapse; Figure (C) Cumulative incidence of transplant related mortality (TRM); (D) OS according to disease status at time of transplant; (E)

OS according to histology subtypes. FL= follicular lymphoma, HL=

Hodgkin Lymphoma, LBCL= large B cell lymphoma, MCL= mantle cell

lymphoma, TCL= T-cell lymphoma.

|

Discussion

The

RIC conditioning and the infusion of unmanipulated PBSC are both

effective and safe: the TRM of 12% is dramatically low compared to

early experiences of allo-HSCT in lymphoma.[14]

The

low incidence of early relapse and the absence of late relapse confirms

a durable GVL effect that cures patients heavily pretreated.

The

GVHD prophylaxis with the administration of Campath before the infusion

of the graft and the single agent ciclosporin did not expose the

patient to the risk of severe forms of acute GVHD. Interestingly, only

seven patients affected with chronic GVHD required systemic treatment,

but none developed recurrent infective complications, and none reported

severe impairment of quality of life from that complication. Also, the

in-vivo T-cell depletion did not endanger the GVL effect nor trigger

lethal viral infections.

These encouraging results can offer a

reflection regarding the costs of transplant compared to CAR-T

therapies, which are the current competitors of allograft in the

third-line setting for B-cell CD19 positive NHL.

The

dissimilarities in prices between cellular therapy products and

allo-HSCT should not drive the clinician's choice of the best treatment

to offer to patients; with this assumption, it is important to remember

that none CAR-T product has the same curative trait of allo-HSCT, as

still 60% of B-cell lymphoma patients are not cured with CAR-T therapy.

Despite

that, it is important to highlight that allo-HSCT will not replace

CAR-T as the standard of care in a third-line setting for CD19-positive

lymphoma due to favourable toxicity profile and its efficacy in

progression-free survival and OS.

Lymphoma subtypes still

lacking an available CAR-T product can be cured with allo-HSCT. Our

study confirms the long-term survival of this strategy and, most

importantly, the safety of our RIC transplant platform. Also, the low

TRM should finally eliminate any doubt about the safety of in-vivo T-cell depletion with Campath.

Our

experience showed that MCL and LBCL can also be cured with allo-HSCT;

this manuscript will feed the new debate on when to offer an allo-HSCT

for these entities.

Considering the availability of highly

effective bridging new therapies to CAR-T infusion, it is not uncommon

to meet patients in complete metabolic remission (CMR) in third- or

fourth-line settings.[6,7] Should CD19-positive

lymphoma be in CMR after the third line of therapy consolidated with

CAR-T infusion or with allo-HSCT? Only a randomized prospective

clinical trial will provide the answer to this dilemma.[15]

Also,

there is evidence of the safety and efficacy of CAR-T infusion after

allo-HSCT; therefore, his strategy should not be considered the

condition sine qua non to preclude CAR-T therapies.[16]

Our

experience shows that the FMC allo-HSCT platform is highly effective

and safe, with low TRM and GVHD rates, and cheaper than CAR-T therapy.

In

conclusion, RIC allo-HSCT can still cure lymphomas, and prospective

clinical trials are needed to further define its role, particularly in

sequencing new strategies for managing CD-19-positive lymphomas.

Acknowledgments

The

authors want to thank all the staff of the haematology department at

King's College Hospital for the care provided to all patients.

References

- Schuster, S. J. et al. Tisagenlecleucel in Adult

Relapsed or Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med.

380, 45-56 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1804980 PMid:30501490

- Neelapu,

S. S. et al. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel CAR T-Cell Therapy in Refractory

Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 2531-2544 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1707447 PMid:29226797 PMCid:PMC5882485

- Kamdar,

M. et al. Lisocabtagene maraleucel versus standard of care with salvage

chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation as

second-line treatment in patients with relapsed or refractory large

B-cell lymphoma (TRANSFORM): results from an interim analysis of an

open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Lond. Engl. 399,

2294-2308 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00662-6 PMid:35717989

- Locke,

F. L. et al. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel as Second-Line Therapy for Large

B-Cell Lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 640-654 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2116133 PMid:34891224

- Wang,

M. et al. KTE-X19 CAR T-Cell Therapy in Relapsed or Refractory

Mantle-Cell Lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 1331-1342 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1914347 PMid:32242358 PMCid:PMC7731441

- Castaneda-Puglianini,

O. & Chavez, J. C. Bispecific antibodies for non-Hodgkin's

lymphomas and multiple myeloma. Drugs Context 10, 2021-2-4 (2021). https://doi.org/10.7573/dic.2021-2-4 PMid:34603459 PMCid:PMC8462994

- Sehn,

L. H. et al. Polatuzumab Vedotin in Relapsed or Refractory Diffuse

Large B-Cell Lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol.

38, 155-165 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.19.00172 PMid:31693429 PMCid:PMC7032881

- Peniket,

A. J. et al. An EBMT registry matched study of allogeneic stem cell

transplants for lymphoma: allogeneic transplantation is associated with

a lower relapse rate but a higher procedure-related mortality rate than

autologous transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 31, 667-678 (2003).

https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bmt.1703891 PMid:12692607

- Hari,

P. et al. Allogeneic transplants in follicular lymphoma: higher risk of

disease progression after reduced-intensity compared to myeloablative

conditioning. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. J. Am. Soc. Blood Marrow

Transplant. 14, 236-45 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.11.004 PMid:18215784 PMCid:PMC2531158

- Genadieva-Stavrik,

S. et al. Myeloablative versus reduced intensity allogeneic stem cell

transplantation for relapsed/refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma in recent

years: a retrospective analysis of the Lymphoma Working Party of the

European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Ann. Oncol. Off.

J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 27, 2251-2257 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdw421 PMid:28007754

- Thomson,

K. J. et al. Favorable long-term survival after reduced-intensity

allogeneic transplantation for multiple-relapse aggressive

non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol.

27, 426-432 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.17.3328 PMid:19064981

- Snowden,

J. A. et al. Indications for haematopoietic cell transplantation for

haematological diseases, solid tumours and immune disorders: current

practice in Europe, 2022. Bone Marrow Transplant. 57, 1217-1239 (2022).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-022-01691-w PMid:35589997 PMCid:PMC9119216

- Sammassimo,

S. et al. A Cellular Therapy with Haploidentical Peripheral

Hematopoietic STEM CELL Transplantation MAY be a Therapeutic Option in

Patients with Relapsed Lymphoma with Chemorefractory Disease. Blood

132, 2189 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2018-99-119752

- Sureda,

A. et al. Reduced-Intensity Conditioning Compared With Conventional

Allogeneic Stem-Cell Transplantation in Relapsed or Refractory

Hodgkin's Lymphoma: An Analysis From the Lymphoma Working Party of the

European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. J. Clin. Oncol.

26, 455-462 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2007.13.2415 PMid:18086796

- Dreger,

P. et al. CAR T cells or allogeneic transplantation as standard of care

for advanced large B-cell lymphoma: an intent-to-treat comparison.

Blood Adv. 4, 6157-6168 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003036 PMid:33351108 PMCid:PMC7756983

- Zurko,

J. et al. Allogeneic transplant following CAR T-cell therapy for large

B-cell lymphoma. Haematologica 108, 98-109 (2023). https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2022.281242 PMid:35833303 PMCid:PMC9827150