Cosimo Colangelo1, Giorgio Tiecco1, Marco Di Gregorio1, Susanna Capone2, Roberto Luigi Allegri2, Maria De Francesco3, Francesca Caccuri3, Arnaldo Caruso3, Francesco Castelli1 and Emanuele Focà1.

1 Department

of Clinical and Experimental Sciences, Unit of Infectious and Tropical

Diseases, University of Brescia-ASST Spedali Civili, Brescia, Italy

2 Unit of Infectious and Tropical Diseases, ASST Spedali Civili, Brescia, Italy

3

Section of Microbiology, Department of Molecular and Translational

Medicine, University of Brescia-ASST Spedali Civili, P. Le Spedali

Civili, 1, 25123, Brescia, Italy.

Correspondence to:

Emanuele Focà, Department Clinical and Experimental Sciences, Unit of

Infectious and Tropical Diseases, University of Brescia and ASST

Spedali Civili di Brescia, 25123 Brescia, Italy.; Tel.:

+39-0303995677.Email:

emanuele.foca@unibs.it

Published: September 1, 2023

Received: July 18, 2023

Accepted: August 14, 2023

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2023, 15(1): e2023052 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2023.052

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

To the editor

Antibiotic

resistance is one of the most relevant problems in hospitals: the

growth of resistant microorganisms in healthcare settings is a

worrisome threat, raising the length of stay, morbidity, and

mortality in patients infected with multidrug resistant bacteria.[1] Moreover, the steady progress in

diagnostic techniques is rising concern about the emergence of new

pathogens which were hardly known in the past years.

Leclercia adecarboxylata is a gram-negative, motile, facultative-anaerobic, oxidase-negative, mesophilic bacillus belonging to the Enterobacteriaceae family.[2] L. adecarboxylata was first described by H. Leclerc in 1962 and was previously known as Enteric group 410 or Escherichia adecarboxylata[3] since Leclercia spp. shares several structural and microbiological properties with the genus Escherichia. Due to those similarities, L. adecarboxylata infections might be more common than what is believed so far since past clinical cases might have been erroneously defined as Escherichia spp.

infections. Moreover, most bacterial assays often could not distinguish

these morphologically and metabolically similar bacteria.[4]

Nevertheless, the availability of more sensitive testing methods (e.g.,

DNA hybridization, computer identification studies) like Matrix

Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time of Flight ("MALDI-TOF") mass

spectrometry allowed a more precise species identification, eventually

leading to the present categorization.[3] L. adecarboxylata

can be found in various specimens and is involved in a wide range of

clinical syndromes commonly related to immunocompromised hosts.

Although most Leclercia spp

isolates show high susceptibility to antibiotics, some multi-resistant

strains have been reported in the literature. Here, we present a

catheter related bloodstream infection caused by a multidrug resistant L. adecarboxylata.

Cae Report

A

38-year-old transgender woman affected by gastric and duodenal diffuse

large B-cell lymphoma in remission was admitted to our Infectious

Diseases Department due to persistent and intense asthenia, weight

loss, and recurring fever episodes. The last rituximab administration

was performed 4 months before, and the antimicrobic prophylaxis was

recently discontinued following bone marrow recovery. The patient

assumed total parenteral nutrition through a tunneled central venous

catheter (CVC) placed 5 months prior to the admission because of

duodenal sub-stenosis subsequent to her hematologic condition.

Moreover, she was affected by chronic hepatitis HBV-correlated, treated

with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, and several episodes of syphilis

reinfection were recorded following her former sex worker activity. No

HIV or HCV co-infections were detected. The chest CT scan performed in

the Emergency Department showed a parenchymal and nodular thickening.

Considering her risk factors for a healthcare-associated infection,

piperacillin/tazobactam (4.5 g every 6 hours/day) was empirically

started. At the admission, no catheter dysfunction and no signs of

catheter-related infection were recorded, and neither an

anti-methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) nor an antimycotic agent was introduced.

A

diagnostic bronchoscopy was also performed, but both microbiological

tests (serology and cultures) and molecular biology assays performed on

the bronchoalveolar lavage gave negative results. However, L. adecarboxylata

was isolated from either peripheral and CVC blood culture performed at

the hospital admission. Catheter-related bloodstream infection (CRBSI)

was then diagnosed since a blood culture drawn from the line was

positive 4 hours earlier than the peripheral vein. This result was also

consistent with the anamnestic data concerning suboptimal domiciliary

management of the CVC, as she referred a sporadic nonsterile handling

of the catheter entry site (for instance, contact with tap water). The

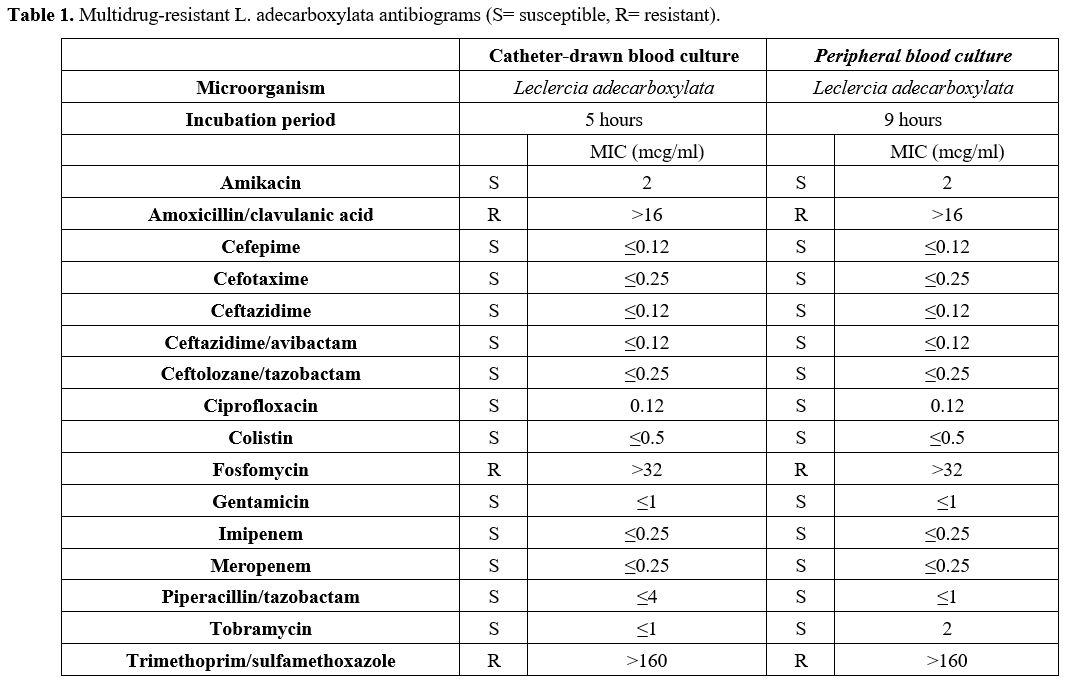

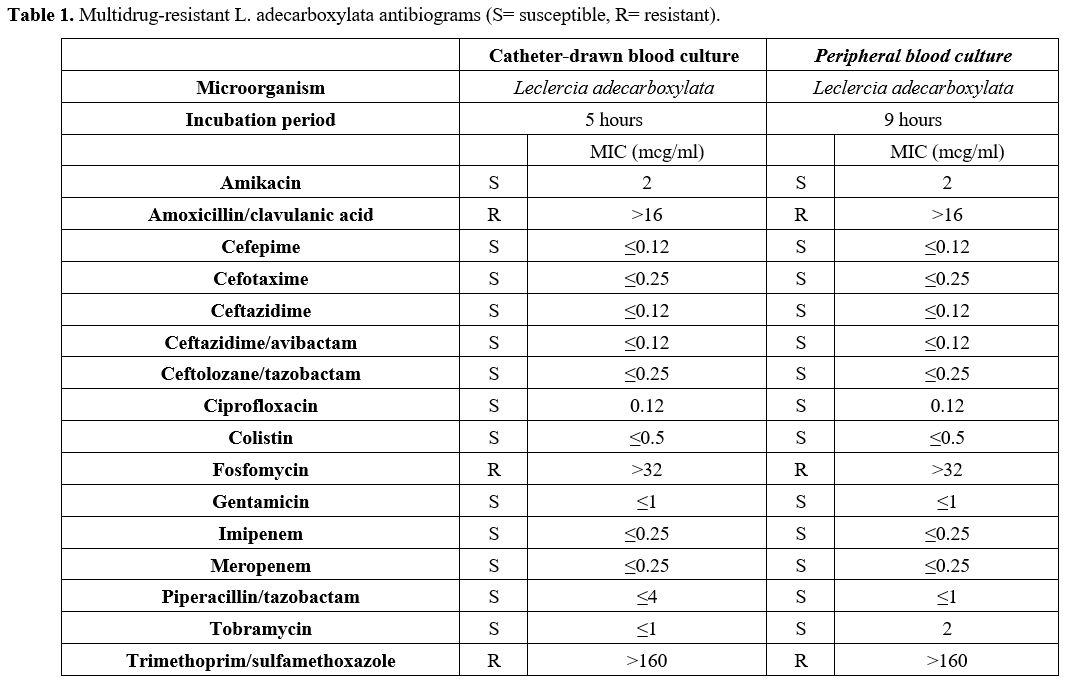

antibiogram showed resistance to amoxicillin/clavulanate, fosfomycin,

and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Table 1),

so piperacillin/tazobactam (MIC ≤1) was maintained, and the catheter

was promptly replaced with a peripherally inserted central catheter

(PICC). A progressive clinical improvement was observed with a

significant reduction in inflammatory markers. On day 14, the targeted

systemic antibiotic therapy was discontinued. An

esophagogastroduodenoscopy was later performed to assess the severity

of the duodenal stenosis. A mass-forming inflammatory non-lymphomatous

tissue was observed, and on day 21, a duodenal prosthesis was placed.

In the following days, the patient was discharged with a semi-liquid

diet and parenteral nutrition to recover a complete oral feeding.

|

- Table 1. Multidrug-resistant L. adecarboxylata antibiograms (S= susceptible, R= resistant).

|

Discussion and Literature Review

Leclercia adecarboxylata is a gram-negative bacillus member of the Enterobacteriaceae family with many structural and microbiological properties in common with the genus Escherichia.[2,3]

The reclassification of this bacteria was achieved thanks to more

sensitive testing methods such as DNA hybridization and computer

identification studies.[2]

L. adecarboxylata has been recently recognized as an emerging pathogen[3,5] for which, thanks to the currently available diagnostic methods, it is possible to obtain an accurate identification.[3] Moreover, several analyses enlighten an ever-increasing number of multidrug-resistant strains[4,5,10] that should highlight the implications of this bacterial infection. L. adecarboxylata

is a ubiquitous microorganism that may be found in aquatic environments

and soil, as well as in the commensal gut flora of certain animals.[2]

In our case, an exposition to an aquatic environment was identified

(use of water to rinse the CVC), similar to a few cases reported in the

literature.[6] Moreover, L. adecarboxylata

might also be isolated from blood culture, skin wounds, peritoneal

fluid, abscesses (e.g., peritonsillar and periovarian), feces, urine,

and synovial fluid.[8] Several underlying conditions might favor L. adecarboxylata

infections: for instance, wounds may act as a direct entry into the

tissue, thus easing the pathogenicity, as well as catheters may be used

as gateways in catheter-related bacteremia or peritonitis could be

developed in patients undergoing dialysis or chemotherapy.[4]

The isolates more commonly mentioned in the literature show a high susceptibility to antibiotics.[4]

They could be controlled with a variety of antibiotics, such as

B-lactams, without witnessing therapeutic failures or needing

second-line treatments.[10] Considering the EUCAST breakpoint for Enterobacterales and given the contemporary resistance to at least [1] antibiotic of 3 different classes showed in our L. adecarboxylata

antibiogram, we consider peculiar our results since, to our best

knowledge, only a few cases of resistant strains have been reported.[2] A more comprehensive evaluation regarding natural antimicrobial susceptibility patterns was reported by Stock et al. from 94 L. adecarboxylata strains

collected from several human specimens: the bacteria were naturally

resistant to numerous antibiotic molecules, such oxacillin,

clarithromycin, erythromycin, roxithromycin, ketolides, rifampin,

glycopeptides, streptogramins, fusidic acid, lincosamides, penicillin G

and fosfomycin but susceptible to most B-lactams, quinolones,

aminoglycosides, tetracyclines, nitrofurantoine, folate pathway

inhibitors, azithromycin and chloramphenicol. In addition,

Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) and New Delhi

metallo-beta-lactamase 1 (NDM)-producing L. adecarboxylata

are also described. Three cases of ESBL producer isolates were

reported: the first case was described from a patient with acute

myeloid leukemia,[2] the second in a 47-year-old female with breast cancer,[10] and the third one in a 50-year-old female with end-stage renal disease.[5] Regarding NDM-producing L. adecarboxylata,

two cases were reported: the first regarding a patient hospitalized for

a foot trauma-related injury, and the second concerned an outbreak of

25 patients in intravenous total parental nutrition.[2]

L. adecarboxylata

might cause monomicrobial infection in immunocompromised patients,

while it is thought that this pathogen generally requires other

coinfecting bacteria to establish infection in immunocompetent

subjects.[4] However, some cases of monomicrobial

infection were described in immunocompetent patients even without

significant underlying comorbidities: only in one case the patient

report a clinical history of chronic disease,[8] while in the other cases, no history indicative of a clinically compromised state was observed.[9] Prevalently, L. adecarboxylata infections are described in adults, but a wound infection and peritonitis were reported in two immunocompetent children.[2] L. adecarboxylata is implicated in several clinical syndromes, such as endocarditis,[2] bacteremia,[4,8] wound infection and cellulitis,[6] pharyngeal and peritonsillar abscesses,[9] urinary tract infections,[3] pneumonia[3] and peritonitis.[3]

Most of these infections, as reported in our case, have been linked to

immunosuppression and the simultaneous presence of central vascular

catheter.[8] Additionally, as it appears from several reports, catheters could be considered important reservoirs for L. adecarboxylata bloodstream infection.[5,7,10] As a matter of fact, L. adecarboxyalta is not a fastidious pathogen: our strain grows both on blood and MacConkey agar.

Regarding treatment options, there are no shared guidelines or recommendations for L. adecarboxylata infections. Most isolates described are sensitive to tested antibiotics.[4] However, as described by Spiegelhauer et al., several strains of L. adecarboxylata

displayed resistance to ampicillin (9/30 isolates resistant) and

fosfomycin (8/10 isolates resistant), so these antibiotics should not

be used as first-line for treatment. Stock et al. described the natural

susceptibility patterns of L. adecarboxylata, showing that most isolated strains were sensible to B-lactams. Thus, Leclercia could be treated with this antibiotic class.[10]

In our case, considering the multi-resistance pattern, we successfully

treated our patient with the administration of piperacillin/tazobactam.

References

- Ricciardi W., Giubbini G., Laurenti P. Surveillance

and control of antibiotic resistance in the Mediterranean region.

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2016, 8(1): e2016036 https://doi.org/10.4084/mjhid.2016.036 PMid:27413528 PMCid:PMC4928537

- Malik K, Davie R, Withers A, Faisal M, Lawal F. A

case of Leclercia adecarboxylata endocarditis in a 62-year-old man.

IDCases. 2021 Mar 27;24: e01091. doi: 10.1016/j.idcr. 2021.e01091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idcr.2021.e01091 PMid:33889491 PMCid:PMC8047457

- Zayet

S, Lang S, Garnier P, Pierron A, Plantin J, Toko L, Royer PY, Villemain

M, Klopfenstein T, Gendrin V. Leclercia adecarboxylata as Emerging

Pathogen in Human Infections: Clinical Features and Antimicrobial

Susceptibility Testing. Pathogens. 2021 Oct 28;10(11):1399. doi:

10.3390/pathogens10111399. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10111399 PMid:34832555 PMCid:PMC8619052

- Spiegelhauer

MR, Andersen PF, Frandsen TH, Nordestgaard RLM, Andersen LP. Leclercia

adecarboxylata: a case report and literature review of 74 cases

demonstrating its pathogenicity in immunocompromised patients. Infect

Dis (Lond). 2019 Mar;51(3):179-188. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2018.1536830.

Epub 2018 Nov 29. https://doi.org/10.1080/23744235.2018.1536830 PMid:30488747

- Alosaimi

RS, Muhmmed Kaaki M. Catheter-Related ESBL-Producing Leclercia

adecarboxylata Septicemia in Hemodialysis Patient: An Emerging

Pathogen? Case Rep Infect Dis. 2020 Jan 21;2020:7403152. doi:

10.1155/2020/7403152. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/7403152 PMid:32089912 PMCid:PMC6996699

- Broderick

A, Lowe E, Xiao A, Ross R, Miller R. Leclercia adecarboxylata

folliculitis in a healthy swimmer-An emerging aquatic pathogen? JAAD

Case Rep. 2019 Aug 5;5(8):706-708. doi:

10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.06.007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.06.007 PMid:31440563 PMCid:PMC6698442

- De

Mauri A, Chiarinotti D, Andreoni S, Molinari GL, Conti N, De Leo M.

Leclercia adecarboxylata and catheter-related bacteraemia: review of

the literature and outcome with regard to catheters and patients. J Med

Microbiol. 2013 Oct;62(Pt 10):1620-1623. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.059535-0.

Epub 2013 Jul 23. https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.059535-0 PMid:23882033

- Shaikhain

T, Al-Husayni F, Al-Fawaz S, Alghamdi EM, Al-Amri A, Alfares M.

Leclercia adecarboxylata Bacteremia without a Focus in a

Non-Immunosuppressed Patient. Am J Case Rep. 2021 Mar 30;22:e929537.

doi: 10.12659/AJCR.929537. https://doi.org/10.12659/AJCR.929537 PMid:33782375 PMCid:PMC8019838

- Bali

R, Sharma P, Gupta K, Nagrath S. Pharyngeal and peritonsillar abscess

due to Leclercia adecarboxylata in an immunocompetant patient. J Infect

Dev Ctries. 2013 Jan 15;7(1):46-50. doi: 10.3855/jidc.2651. https://doi.org/10.3855/jidc.2651 PMid:23324820

- Shin

GW, You MJ, Lee HS, Lee CS. Catheter-related bacteremia caused by

multidrug-resistant Leclercia adecarboxylata in a patient with breast

cancer. J Clin Microbiol. 2012 Sep;50(9):3129-32. doi:

10.1128/JCM.00948-12. Epub 2012 Jul 3. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00948-12 PMid:22760051 PMCid:PMC3421816

[TOP]