Congenital

sideroblastic anemias (CSAs) are inherited diseases of mitochondrial

dysfunction due to defects in heme biosynthesis, iron-sulfur cluster

biogenesis, generalized mitochondrial protein synthesis, or the

synthesis of specific mitochondrial proteins involved in oxidative

phosphorylation.[1] CSAs are

characterized by the

accumulation of ring sideroblasts in the bone marrow, with ineffective

erythropoiesis and increased serum and tissue iron levels. X-linked

sideroblastic anemia (XLSA) is the most common form of CSA and is

attributed to 5-aminolevulinate synthase (ALAS2) mutations.[2] Here, we presented a de novo mutation in

ALAS2 in a

Chinese patient with CSA and a good response to pyridoxine treatment.

The

proband was a 32-year-old female who was the family's only child. The

family history was unremarkable, and the parents were

non-consanguineous. At age 27, the proband required blood transfusions

during her first pregnancy due to severe anemia. At that time, due to

the low level of vitamin B12, the proband was incorrectly diagnosed

with megaloblastic anemia.

At age 32, the proband again

developed severe anemia during her second pregnancy and required a

blood transfusion. Physical examination revealed that the spleen of the

proband was enlarged to 5 cm below the costal margin. A hemogram at

presentation to our center revealed a hemoglobin level of 5.9 g/dL

(reference value: 12.0–15.0 g/dL), a red blood cell count of 1.41×1012/L

(reference value: 3.8–5.1×1012/L),

a mean corpuscular volume of 127.7 fL (reference value: 80–100 fL),

mean corpuscular hemoglobin of 41.8 pg (reference value: 27–34 pg), a

mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration of 32.8 g/dL (reference

value: 31.6–35.4 g/dL), a reticulocyte percentage of 2.35% (reference

value: 0.5–1.5%), a white blood cell count of 3.95×109/L (reference

value: 3.5–9.5×109/L),

and a platelet count of 132×109/L (reference

value: 100–300×109/L). A

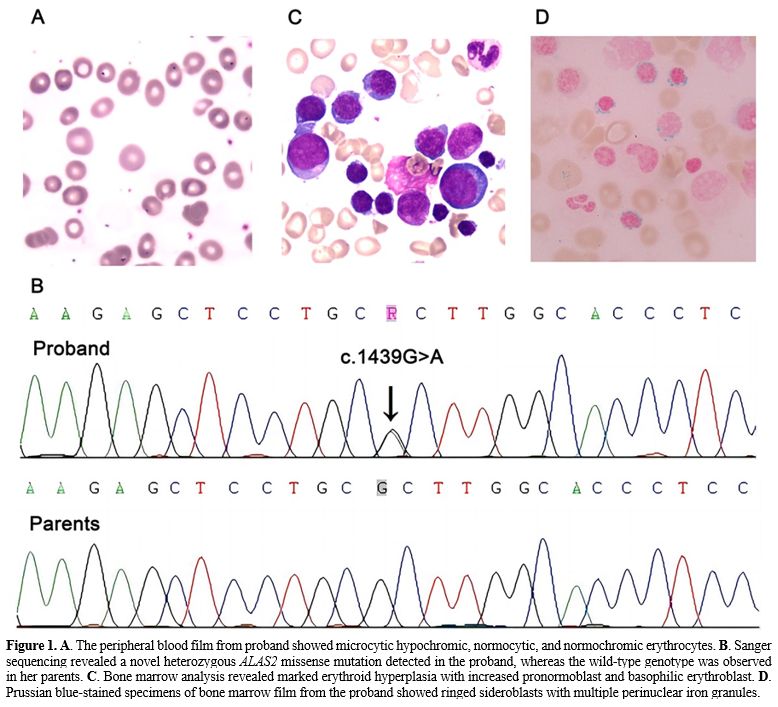

peripheral blood smear was dimorphic, including microcytic hypochromic,

normocytic, and normochromic erythrocytes (Figure 1A).

Serum biochemical tests revealed a total bilirubin level of 15 μmol/L

(reference value: 0–23 μmol/L), an indirect bilirubin level of 8.7

μmol/L (normal range: 5–18 μmol/L), and a lactate dehydrogenase level

of 117 U/L (reference value: 120–250 U/L). Iron metabolism testing

revealed that serum ferritin, serum iron, and transferrin were 751.4

ng/mL (reference value: 4.63–204 ng/mL), 37.18 μmol/L (reference value:

7–30 μmol/L), and 1.57 g/L (reference value: 1.7–3.4 g/L),

respectively. Levitt’s CO breath test showed that the erythrocyte life

span of the proband was 24 days (normal range: 70–140 days). Laboratory

tests for megaloblastic anemia, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, paroxysmal

nocturnal hemoglobinuria, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency,

thalassemia, and hepatopathy were negative.

Next-generation

sequencing of the proband and her family was carried out to investigate

underlying variants associated with anemia in the proband. A de novo

heterozygous missense mutation of ALAS2:

c.1439G>A was found and further confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Figure 1B).

The c.1439G>A mutation led to a substitution of a conserved

arginine

to histidine at residue 480 (p.Arg480His) in exon 9 of the ALAS2

protein. Given the ALAS2

mutation, a diagnosis of CSA was suspected.

Bone marrow analysis revealed marked erythroid hyperplasia with

increased pronormoblast and basophilic erythroblast (Figure 1C).

In Prussian blue-stained specimens, a bone marrow smear showed

erythroid hyperplasia with a 66% proportion of total sideroblasts, and

the proportion of ring sideroblasts was 16% (Figure 1D).

Chromosome analysis revealed a normal karyotype (46, XY). A bone marrow

biopsy showed hyperactive hyperplasia and no increase in reticulin

fibers (MF0). Following the diagnosis of SA in the bone marrow, further

investigations were conducted, including tests for pyridoxine, zinc,

lead, and copper levels and chromosomal microarray analysis for

myelodysplastic syndromes. All tests came back normal. The proband was

thus diagnosed with CSA caused by this mutation of the ALAS2 gene. The

proband had a good response to pyridoxine treatment, but her ferritin

level gradually rose to 925.85 ng/mL.

XLSA

typically affects younger males due to an X-linked recessive pattern of

inheritance. However, as a result of familial-skewed inactivation of

the normal X chromosome, females with ALAS2 mutations may

have a late-onset clinical phenotype, as with the proband in this

study.[3]

The management of CSA remains primarily supportive rather than

definitive. ALAS2 catalyzes the first step of the heme biosynthetic

pathway by condensing glycine and succinyl-CoA to form

delta-aminolevulinic acid in the presence of pyridoxal 5’-phosphate,

which is the metabolite of vitamin B6.[4]

Pyridoxine

can enhance the activity of the ALAS2 enzyme, and more than half of

XLSA patients are responsive to supplementation with pyridoxine.[5] More than 100 distinct mutations in

the ALAS2

gene have been reported. Most disease-associated variants occur in

exons 5 and 9; the latter contains the pyridoxal-binding amino acid.[2] This finding was confirmed by the

good response to pyridoxine treatment observed in the proband.

Patients

with CSA are prone to iron overload, whether pyridoxine-responsive or

not, regardless of red blood cell transfusions. Iron overload is partly

attributed to reduced hepcidin level secondary to ineffective

erythropoiesis, which promotes intestinal iron absorption.[6]

The ferritin level of our reported XLSA patient increased gradually. It

is therefore necessary to monitor regularly patients' clinical,

laboratory, and radiological parameters to detect these long-term

complications. Anecdotal reports of hematopoietic stem cell

transplantation in CSA describe effective remission.[7]

However, early diagnosis and management of CSA remain fundamental,

especially as iron overload should be kept at a minimum to ensure a

better outcome of a potential future transplantation. Additionally,

developing definitive treatments for CSA is an area of need.

Preclinical studies and clinical trials are essential to determine

whether novel agents such as luspatercept or approaches involving gene

therapy for CSA would benefit its treatment.[8]

In conclusion, we identified a novel ALAS2

missense mutation causing CSA in the Chinese population. Our findings

will provide valuable insights to broaden the clinical phenotypic

spectrum of CSA and improve understanding of ALAS2 gene variants.