Macoura Gadji1,2,*, Youssou Bamar Gueye1,*, David Motto1 and Saliou Diop1,3.

1 National

Centre of Blood Transfusion (NCBT) of Dakar, Senegal,

2

Service of Haematology & Oncology-Haematology (HBOH), Department of

Biology and Applied Pharmaceutical Sciences; Faculty of Medicine,

Pharmacy and Odonto-Stomatology (FMPOS), University Cheikh Anta Diop of

Dakar (UCAD), Dakar, Senegal.

3 Service of Haematology,

Department of Medicine; Faculty of Medicine, Pharmacy and

Odonto-Stomatology (FMPOS), University Cheikh Anta Diop of Dakar

(UCAD), Dakar, Senegal.

* The authors contributed equally to this work..

Correspondence to: :

Prof. Macoura Gadji: PharmD., Ph.D. Head of HBOH/FMPOS/UCAD. Address 1:

CNTS BP 5002 Dakar Fann PtE, Dakar, Senegal. Tel. (221) 776813160.

E-mail:

macoura.gadji@ucad.edu.sn

Published: January 01, 2024

Received: October 26, 2023

Accepted: December 10, 2023

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2024, 16(1): e2024008 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2024.008

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

To the editor

Blood transfusion is a supportive therapy improperly performed in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA).[1]

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends establishing national

blood transfusion systems based on voluntary unpaid blood donors.

Unfortunately, countries of SSA continue to struggle with inadequate

resources and infrastructure for a safer blood supply despite the

important need for blood transfusion to treat severe and chronic anemia

resulting from tropical diseases, sickle cell disease and other

haemoglobinopathies, severe parasitic infections, nutritional anaemia

in a condition of low or moderate safety of transfusion.[1,2]

As a routine practice in front of a deficit of blood products,

prescribers appeal to the patient's family members to donate to

minimize the impact of blood shortages on patient care. This type of

family-aware blood donors, known as familial/replacement donors (FRBD),

despite the risk of transfusion safety, account for 20% of blood

donation in Senegal, for 88.6% in Nigeria,[3] and in

several other African countries (69.5% in Yaounde and 80.2% in Sierra

Leone). During the COVID-19 pandemic, the supply of safe blood was

threatened by the measures taken to fight this virus spread, like the

advice to stay at home and the fear of infection at the blood

transfusion centers, limiting donors' access to blood services. These

measures to prevent the spreading of the COVID-19 pandemic have led to

a sharp decline in stocks of blood products and to an increase of the

number of FRBD. To evaluate the impact of this COVID-19 pandemic on the

infectious safety of blood transfusion, we performed a descriptive and

analytical study carried out during the first period of COVID-19,

aiming to compare the seroprevalence of HIV, HBV, HCV, and syphilis in

FRBD versus voluntary unpaid

blood donors (VUBD). The goal is to evaluate the threats to familial

blood donation during catastrophic periods such as pandemics, wars, and

so on and to help define a policy in improving the recruitment,

retention, and medical screening of blood donors in SSA. After

answering a pre-donation questionnaire, a social worker received the

blood donor, who opened the donor file with an identifier in the donor

management software (Inlog®). At this stage, the blood donor indicates

whether he has come for a voluntary or family/replacement donation.

Subsequently, the donor was interviewed by the medical practitioner for

the pre-donation medical screening, based on questionnaires of

effective blood donors, to verify if the serological results were

indeterminate or discordant in our analysis. The donors' serology and

blood grouping results were taken from the Inlog® software. The

serological tests for HBV, HIV, and HCV were performed with AlinityTM automated, which uses ChemiflexTM

(ABBOTT, Germany) chemiluminescence technology to screen for infectious

markers. According to the manufacturer's instructions, the Rapid Plasma

Reagent test was used to find treponemal antibodies. The determination

of ABO and Rh, blood group typing, was performed with the standard

methods as a globular method with monoclonal antibodies of blood

grouping antisera and serologic method with red blood cells (globule

tests) on a plate. Data analysis was performed using Epi-info software

(version 3.5.4). This software allows the application of the Chi2 test

to accept or reject the statistical hypotheses posed (p < 0.05)

and to give the odd ratio (OR) between the dependent variables and the

independent variables, as well as their 95% confidence interval (CI).

During this pandemic period, 5002 blood donors were collected at the

fixed location of the National Centre of Blood Transfusion. The mean

age of the donors was 32.23 ± 9.9 years. Young people aged from 25 to

34 years constitute the majority of blood donors (35.7%). Male donors

represented 75%; new donors (52.6%) and FRBD (54%) were the majority of

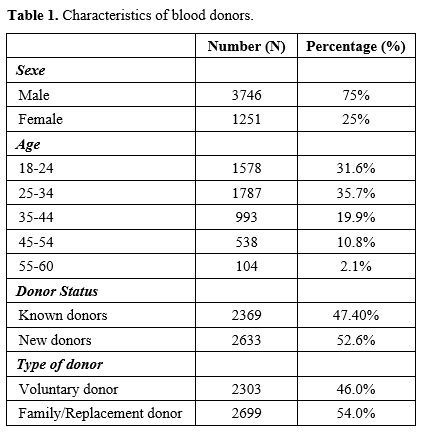

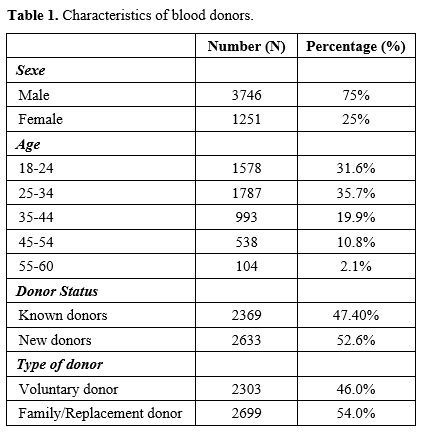

blood donors (Table 1). Analysis of donor status by type of donation showed more FRBD donors among new donors (66.7%) (p˂0.001). Voluntary donors were more represented in the regular known donor group (63.8%) (p<0.001).

Blood group O Rh+ was more represented in this population (49.4%),

followed by group A+ (20.6%) and B+ (17.8%); Rh-negative donors

represented only 8.8%. This study revealed a higher number of FRBD than

VUBD (p <0.001) during the

blood shortage due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This was the case in

Nigeria, where 61.7% of paid donors and 30.6% of family/replacement

blood donors were reported. All these results highlight that family

replacement blood donation is still a common practice in Africa and is

exacerbated during times of blood shortage such as COVID-19 pandemic

period. The prevalence of transfusion transmissible infections (TTIs)

was statistically higher in the FRBD group (9.2%) compared to VUBD

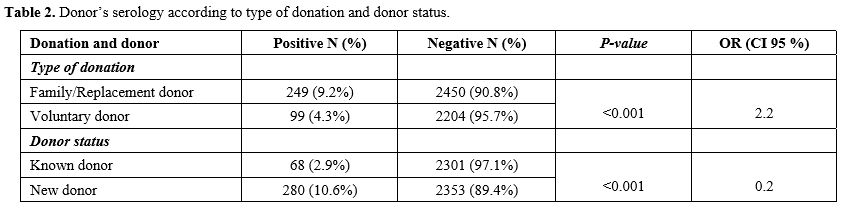

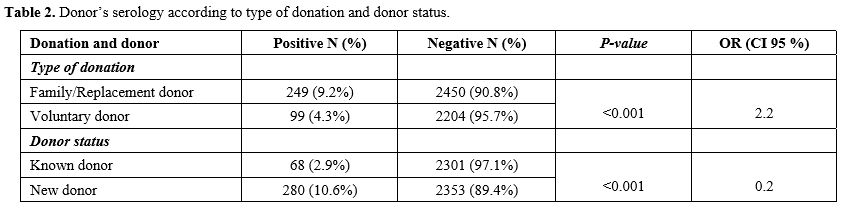

(4.3%) (p<0.001). The prevalence of infectious markers was higher in new unknown donors (10.6%) than in regular known donors (2.9%) (p<0.001, OR=1.9) (Table 2).

|

Table 1. Characteristics of blood donors. |

|

Table 2. Donor’s serology according to type of donation and donor status.

|

The

prevalence of TTI markers was statistically higher in the new FRBD

group compared to the new VUBD population (11.7% vs. 8.3%) (p=0.003,

OR=1.4). The comparison of HIV, HCV and syphilis marker

seroprevalences, only in new donors, showed no statistically

significant difference between both categories of new FRBD and new VUBD

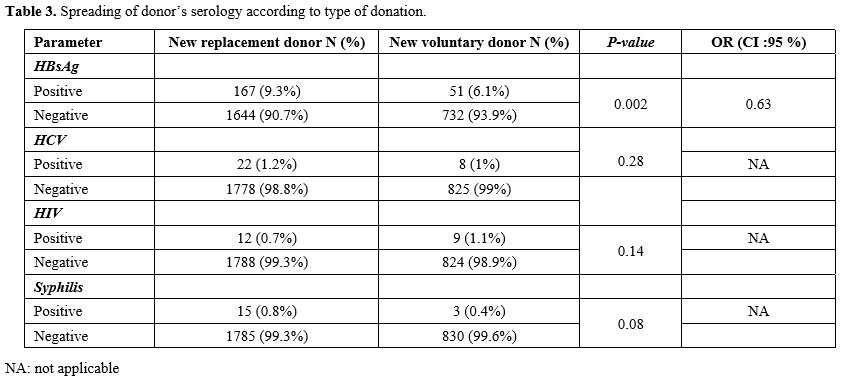

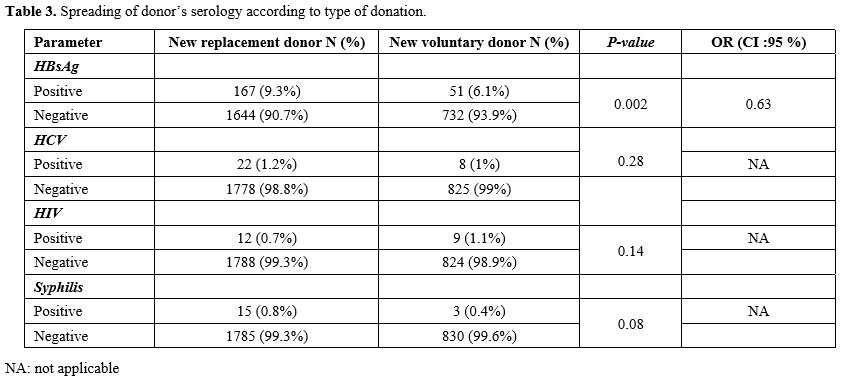

(p>0.05). However, for HBV, the prevalence was higher in new FRBD with a statistically significant difference (p=0.002; Table 3).

Our results showed that FRBD increases the risk of having at least one

positive serological result for one of the infectious markers tested (p ˂ 0.001; OR = 2.2), in line with different studies in the World.[4]

Furthermore, a statistically higher seroprevalence of infectious agents

in new donors was found compared to regular donors in Africa, notably

in Mali and Niger.[5] The comparison of HIV, HCV, and

syphilis seroprevalences between new FRBD and new VUBD showed no

statistically significant difference in the prevalence for these three

markers. However, a statistically higher prevalence among new FRBD for

HIV, HCV, and syphilis markers was found in the Democratic Republic of

Congo (DRC).[6] Previously, in Cameroon, a study found a statistically higher prevalence of HCV and HIV in first-time FRBD.[7]

In our study, the lack of statistically significant difference between

voluntary and replacement donors for these three markers could be

explained by the effectiveness of medical screening and the low

prevalence of these infectious markers, especially HIV, in the general

population. However, in our study, the prevalence of HBV is

significantly higher in new FRBD (6.4%) than in new VUBD (2.9%; (p<0.001). These results are similar to those of the study in the DRC, with higher values in the new FRBD.[6]

Nonetheless, in Tanzania, there is no statistical difference in the

prevalence of HIV, HCV, and syphilis, but the prevalence of HBV was

significantly higher in new FRBD.[8] This higher

prevalence of HBsAg in FRBD could be explained by the risk factor of

transmission linked to living in a common household with a person

infected with HBV. Indeed, previous studies revealed that the HBV

virus can be transmitted between people living in the same household.[9,10]

Finally, it is obvious that HBV-carried parents increase the risk of

virus transmission to their children and relatives. The COVID-19

pandemic impacted the proper supply of blood products by increasing

more than 2X the number of FRBD. Thus, replacement donations have

played an important role in limiting the damage observed with blood

shortages despite the increased risk of TTIs. Our study highlights and

strengthens the WHO recommendations for selecting voluntary unpaid

donors. Our results will allow to continue collecting

family/replacement donors in blood shortage situations while taking

into account the prevalence of infectious blood markers in the new

donor population.

|

- Table 3. Spreading of donor’s serology according to type of donation.

|

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the blood donors who made this study feasible.

References

- Gadji M, Cobar G, Thiongane A, Senghor AB, Seck R,

Faye BF, et al. Red blood cell alloantibodies in pediatric transfusion

in sub‐Saharan Africa: A new cohort and literature review. eJ Haem.

2023 May;4(2):315-23. https://doi.org/10.1002/jha2.645 PMid:37206261 PMCid:PMC10188460

- Ogar

CO, Okoroiwu HU, Obeagu EI, Etura JE, Abunimye DA. Assessment of blood

supply and usage pre- and during COVID-19 pandemic: A lesson from

non-voluntary donation. Transfus Clin Biol. févr 2021;28(1):68‑72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tracli.2020.10.004 PMid:33080420 PMCid:PMC7836417

- Shittu

AO, Olawumi HO, Omokanye KO, Ogunfemi MK, Adewuyi JO. The True Status

of Family Replacement Blood Donors in a Tertiary Hospital Blood Service

in Central Nigeria. Africa Sanguine Dec 2019 , 21(2) : 11-14. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:214503320

- Ibrahim

Y. A, Mona A. I, Abeer A. S, Mary R. The degree of safety of family

replacement donors versus voluntary non-remunerated donors in an

Egyptian population: a comparative study. Blood Transfus. 2014 Apr;

12(2): 159-165. https://doi.org/10.2450/2012.0115-12. PMID: 23245714; PMCID: PMC4039696.

- Mayaki

Z, Dardenne N, Kabo R, Moutschen M, Sondag D, Albert A, and al.

Séroprévalence des marqueurs infectieux chez les donneurs de sang à

Niamey (Niger). Rev d'Épidémiologie Santé Publique. 2013 June

;61(3):233‑40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respe.2012.12.018 PMid:23642899

- Lushamba

C J-PC, Bukombe WB, Kachelewa KB, Maheshe TB, Bisangamo CK. Transfusion

Safety at Dr Rau/Ciriri Hospital, East of Democratic Republic of Congo.

Annales des Sciences de la Santé.2018 , 1(19): 25-35. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:216870995

- Ankouane

F, Noah Noah D, Atangana MM, Kamgaing SR ,Guekam PR , M. Biwolé MS.

Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C virus, HIV-1/2 et la syphilis chez

les donneurs de sang à l'hôpital central de Yaoundé dans la région du

centre du Cameroun. Transfus Clin Biol 2016, ;23(2):68‑72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tracli.2015.11.008 PMid:26791918

- Mohamed

Z, Kim JU, Magesa A, Kasubi M, Feldman SF, Chevaliez S, and al. High

prevalence and poor linkage to care of transfusion-transmitted

infections among blood donors in Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania. J Viral

Hepat. 2019 June; 26(6):750. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvh.13073 PMid:30712273 PMCid:PMC6563112

- Chakravarty R.

, Chowdhury A., Chaudhuri S., Santra A., Neogi M., Rajendran K.. and al. Hepatitis B infection in Eastern Indian families:

need for screening of adult siblings and mothers of adult index cases.

Public Health, 119 (2005), pp. 647-654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2004.09.007 PMid:15925680

- Dumpis U., Charles Holmes E., Mendy M., Hill A., Thursz M., Hall A., and

al. Transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in Gambian families

revealed by phylogenetic analysis.J Hepatol, 35 (2001), pp. 99-104. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-8278(01)00064-2 PMid:11495049