Ugo Testa1, Patrizia Chiusolo2,3, Elvira Pelosi1, Germana Castelli1 and Giuseppe Leone3.

1

Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Roma.

2

Dipartimento di Diagnostica per

Immagini,

Radioterapia Oncologica ed

Ematologia, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino

Gemelli IRCCS, Roma,

Italy. Sezione di Ematologia.

3 Dipartimento d Scienze Radiologiche ed

Ematologiche, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Roma, Italy

Published: March 01, 2024

Received: January 22, 2024

Accepted: February 13, 2024

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2024, 16(1): e2024031 DOI

10.4084/MJHID.2024.031

This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

|

Abstract

Chimeric

antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy has revolutionized the

treatment of B-cell lymphoid neoplasia and, in some instances, improved

disease outcomes. Thus, six FDA-approved commercial CAR-T cell products

that target antigens preferentially expressed on malignant B-cells or

plasma cells have been introduced in the therapy of B-cell lymphomas,

B-ALLs, and multiple myeloma.

These therapeutic successes have

triggered the application of CAR-T cell therapy to other hematologic

tumors, including T-cell malignancies. However, the success of CAR-T

cell therapies in T-cell neoplasms was considerably more limited due to

the existence of some limiting factors, such as: 1) the sharing of

mutual antigens between normal T-cells and CAR-T cells and malignant

cells, determining fratricide events and severe T-cell aplasia; 2) the

contamination of CAR-T cells used for CAR transduction with malignant

T-cells. Allogeneic CAR-T products can avoid tumor contamination but

raise other problems related to immunological incompatibility.

In

spite of these limitations, there has been significant progress in CD7-

and CD5-targeted CAR-T cell therapy of T-cell malignancies in the last

few years.

|

Introduction

T-cell

acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALLs) represent about 25% of adult ALLs

and 10-15% of pediatric ALLs. T-ALLs derive from the leukemic

transformation of thymic progenitors during T-cell development through

the accumulation of genetic abnormalities.

According to the

differentiation stage and the expression of some membrane antigens,

T-ALLs were classified as early/precortical, cortical, and mature. With

the advent of studies of molecular analysis of genetic alterations

(next-generation sequencing) and cytogenetic studies, T-ALLs have been

classified according to the presence of these genetic alterations. Two

types of genetic abnormalities are observed in T-ALLs: type A

aberrations, characterized by ectopic activation of transcription

factors dependent upon chromosomal rearrangements or deletions; type B

alterations, related to additional genetic lesions that are required

for full leukemia transformation.[1] According to the

presence of genetic alterations, four subtypes of T-ALL have been

identified, including early thymocyte progenitor (ETP)/immature ALL,

TLX, TLX1/NKX2.1, and TAL/LMO. ETP-ALLs are characterized by the

expression of hematopoietic stem cell markers such as CD34, aberrant

HOX4, and MEF2C gene expression, recurrent mutations in the IL7

signaling cascade, and high BCL2 protein expression. The TLX subgroup

is characterized by expression of the γ/δ

T-cell receptor, driver genetic events activating either TLX3 or HOXA

transcription factors. The TLX1/NKX2.1 subgroup is characterized by

driver genetic events involving either TLX1 or NKX2.1 transcription

factors and by the occurrence of NUP214-ABL1

fusion in TLX-rearranged cases. The TAL/LMO subgroup is characterized

by the expression of mature-cell membrane markers, driver activation of

the TAL1 and LMO2 transcription factors, and recurrent PTEN mutations.[2-3]

The

treatment of ALLs, including T-ALL, has markedly progressed over the

past three decades, and consistent improvements in overall survival

have been obtained, particularly for children younger than 15 years.[4]

However, the survival of adult T-ALL patients was clearly lower than

that observed for children and young adults. Furthermore, patients with

relapsed/refractory disease have a poor outcome, with survival ranging

from 10-25%.[4]

T-cell lymphomas are a type of

non-Hodgkin lymphoma involving the malignant transformation of T-cells;

four major subtypes have been characterized, including extranodal

T-cell lymphoma, cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (Sezary syndrome and

mycosis fungoides), anaplastic large cell lymphoma and

angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Considerable progress has been made

in understanding the molecular pathogenesis of these disorders, leading

to an improvement in their therapy; however, for patients with

refractory or relapsed disease, outcomes are generally poor.[5]

Chimeric

antigen receptor (CAR) is a novel cell-based immunotherapy exhibiting

considerable efficacy. CAR-T cells are engineered to specifically

recognize an antigen expressed on a cell in a major histocompatibility

complex (MHC) in an independent manner and, consequently, kill this

cell. CAR-T cell production involves three steps, consisting of first

obtaining healthy cells from a patient or a donor, then engineering

T-cells using genomic techniques, such as lentiviral gene transduction

and/or gene editing, and, finally, infusing CAR-T cells thus armed to

recognize and to kill cancer cells. CAR-T cell therapy has obtained

considerable success in the treatment of B-cell malignancies, such as

B-cell lymphomas and B-acute lymphoblastic leukemia. These developments

in the treatment of several hematological malignancies have triggered

the exploration of CAR-T cell therapy in T-cell malignancies; however,

the extension of CAR-T cell therapy to T-cell malignancies is

particularly challenging for the co-expression of many cell membrane

antigenic targets between normal and malignant cells.[6]

CAR-T cell therapy of T-ALL based on CD7 targeting

CD7

is a membrane antigen highly expressed in T-ALL cells. CD7 is a cell

membrane glycoprotein with a molecular weight of 40 KDa, pertaining to

the immunoglobulin supergene family. CD7 is considered a good potential

target for the treatment of T-ALLs and T-cell lymphomas.[7]

More

recently, CAR-T lymphocytes engineered to express anti-CD7 have been

used as therapeutic agents for T-ALL and T-cell lymphoma treatment.

However, since CD7 is expressed on normal T lymphocytes and NK cells,

the uninhibited CD7 expression on the cell membrane of T-lymphocytes

would determine a fratricidal killing; therefore, the generation of

CAR-T cells targeting CD7 requires the abrogation of blocking of CD7 on

the membrane of T-lymphocytes before their engineering with a CAR

encoding anti-CD7.[8]

Various methods have been

used to inhibit/block CD7 expression on T cells for the development of

CAR-T cells targeting CD7: gene editing, protein blockers, and natural

selection.

CD7 CAR-T cells based on gene editing.

Two types of gene editing were used for the generation of CD7 CAR-T

cells: CRISPR/CAS9 gene editing and base editor gene editing.

CRISPR/CAS9 gene editing.

The CRISPR/CAS9 gene-editing systems involve two components: the

caspase 9 (CAS9) which cleaves the DNA, and a guide RNA (CRISPR,

clustered regularly interspersed short palindromic repeats), directing

CAS9 at the level of specific DNA sequences: thus, designing guide RNAs

targeting specific DNA sequences, it is possible to use CAS9 to

introduce double-strand breaks into DNA, thus generating a specific

gene knockout. Preclinical studies have shown that CD7KO

CD7 CAR-T cells are prevented from fratricide, proliferate, and exert

specific antitumor activity against malignant T leukemic cells.[8]

Autologous

T cells or allogeneic T cells can be used for the generation of CD7

CAR-T cells. The generation of CD7 CAR-T cells generated from

autologous T-cells obtained from the patient is limited: by the

difficulty of obtaining an appropriate number of healthy cells from

patients for the preparation of CAR-T cells; the duration of the

procedure required for the generation of CAR-T cells; the risk of a

possible contamination of T cells used for CAR-T cell generation with

leukemic or lymphoma T-cells; the considerable cost of autologous,

individualized, CAR-T cell preparations.[6]

Allo-CAR-T

cells do not have these limitations; however, these CAR-T have other

problems, mainly related to the immunological compatibility: the host

immune system may reject allo-CAR-T cells, recognized as not-self; the

development of graft versus host disease (GvHD) of donor T cells

against the host.[9]

Gene editing can be

used to knock out the T-cell receptor gene to decrease the

immunological incompatibility of T cells, eliminating the human

leukocyte antigen (HLA) class II gene and CD52.[10] Using this approach, Xie et al. recently reported the development of “universal” CAR-T cells CD7-/-, TRAC-/-, CD7UCAR.[10] These cells efficiently proliferate and specifically induce the killing of primary T-ALL cells in vitro,

with high secretion of proinflammatory cytokines; furthermore, these

CAR-T cells are also able to significantly reduce tumor load and extend

mice survival in T-ALL models.[10]

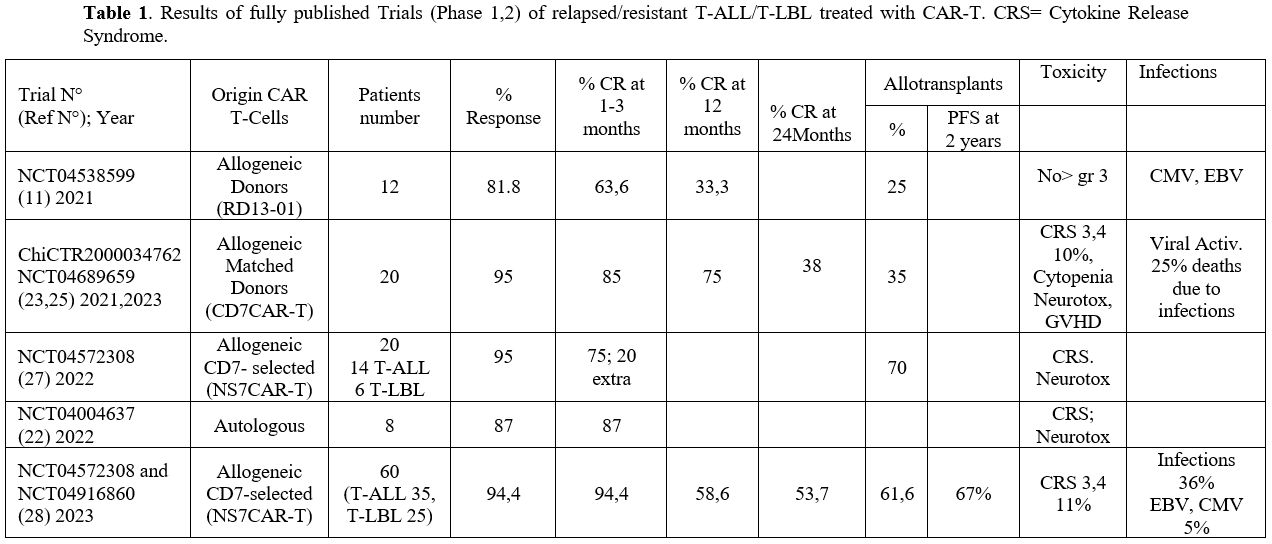

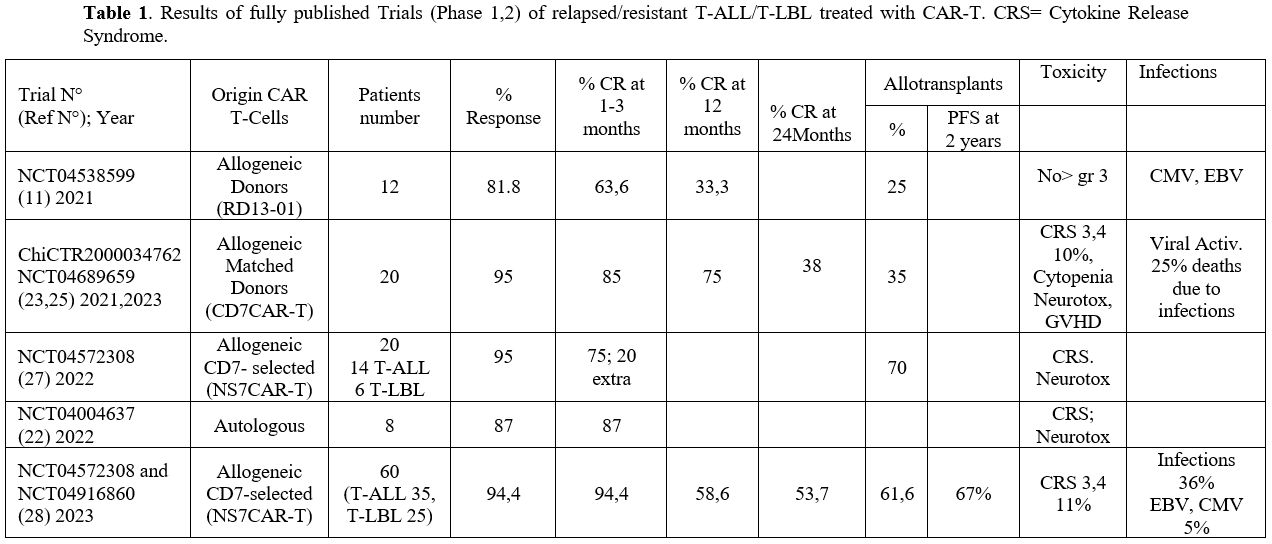

Hu et al. reported the first clinical trial using CD7 targeting CAR-T cells (RD13-01) with genetic modifications (knockout of CD7/TRAC/RFX5-related genes) to resist fratricide, GvHD, and allogeneic rejection and to potentiate antitumor activity.[11] A phase I trial using these CAR-T cells enrolled 12 patients (11 with T-ALL/T-lymphoma and 1 with CD7-expressing AML).[11]

4-wk post-infusion, 9/11 patients showed OR and 7/11 a CR; 3 patients

were bridged to allo-HSCT. With a median of 10.5 months, 4 patients

remained in CR.[11] (Table 1)

Zhang et al recently reported the results of a phase I study involving

the treatment of 7 T-ALL and 3 T-LBL patients with RD13-01 CAR-T cells,[12]

80% of patients achieved a CR and 7/8 responding patients had an

MRD-negative status; interestingly, three patients who had failed prior

autologous CD7 CAR-T cell therapy achieved a CR following treatment

with CD7 allo-HSCT and 4/6 remained progression-free up to 315 days.[12]

Four out of seven patients with extramedullary disease (EMD) obtained

EMD CR at the median day 30. 2/6 patients relapsed without CD7 loss and

subsequently died.[12] Only one patient experienced grade 3 cytokine release syndrome, and one patient experienced grade 3 neurotoxicity.[12]

These observations support additional studies to define better the

safety and efficacy of RD13-01 products in the treatment of patients

with T-ALL and T-LBL.

|

- Table

1. Results of fully published Trials (Phase 1,2) of relapsed/resistant

T-ALL/T-LBL treated with CAR-T. CRS= Cytokine Release Syndrome.

|

Leedom

and coworkers reported the development of WU-CART-007, an allogeneic

CAR-T cell therapy for T-cell malignancies manufactured using normal

T-cells by deletion of CD7 and TRAC using normal T-cells by deletion of

CD7 and TRAC using CRISPR/CAS9 gene editing (controlling the occurrence

of possible off-target events by GUIDE-Seq), followed by CAR

transduction with a lentiviral vector expressing a high-affinity and

highly specific anti-CD7, cell expansion and depletion of residual

TCRA/B+ cells.[13] WU-CART-007 cells exerted a potent antitumor activity both in vitro and in vivo through CD7 targeting.[13]

Using WU-CART-007 cells, Ghobadi et al. reported the results of phase I

/II study WU-CART-007-1001 involving the enrolment of 12 patients with

R/R T-ALL or T-LBL, treated at four dose levels (100, 300, 600, 900

million of cells per infusion).[14] WU-CART-007

showed manageable toxicity, with treatment-related adverse events in

25% of patients; the CRR for patients treated at dosage level ≤2 was

43%.[14]

Li et al. reported the development of

allo-CAR-T cells GC027 based on the lentiviral transformation with a

CAR-expressing anti-CD7 of normal healthy T-lymphocytes in which TCR

and CD7 genes were silenced using CRISPR/CAS9 gene editing system.[15]

The safety and the efficacy of GC027 CAR-T cells were initially

explored in two patients with refractory/relapsed T-ALL, both achieving

a complete response.[15] More recently, the same

authors reported the results of the expanded study with GC027 CAR-T

cells involving the enrolment of 12 R/R T-ALL patients: 11/12 patients

displayed rapid eradication of leukemic T-lymphoblasts and reached CR

one month after CAR-T cell infusion (CR rate 91.7%). Three out of four

patients with EMD showed complete remission of the lesions.[16]

Infused GC027 cells expanded rapidly in vivo and reached a peak of

expansion 5-10 days after their infusion; in most patients, GC0278

cells were not detectable 4 weeks after infusion.[16] Notably, one patient had a PFS of >3 years.[16] The toxicity profile was manageable.[16]

Base Editing.

Base editing is an emerging genome technology consisting of the

generation of programmable single base pair changes at the level of

defined genetic loci with high specificity, precision, and efficiency.

In this technique, adenine base editors (EBEs) and cytosine base

editors (CBEs) combine a single-stranded DNA deaminase enzyme with a

nuclease, CAS9, to install A⋅T to G⋅C or C⋅G to T⋅A point mutations at

specific genomic target sites, respectively.[15]

Since both ABEs and CBEs operate without causing double-strand breaks,

they produce efficient on-target editing, markedly reducing the risks

of editing complex genome rearrangements observed with nuclease

editing.[17]

Using this technology, DiOrio et

al. developed 7CAR8, a CD7-directed allogeneic CAR-T generated

introducing four simultaneous base edits: CD7, TCRα, CD52, and PD1.[17] In preclinical studies, the 7CAR8-T cells were shown to be highly efficacious in vitro and in vivo T-ALL models.[17]

In

2022, the CD7 CAR-T basic editing clinical trial (ISRCTN 15323014)

started. In this trial, healthy donor T cells were base-edited at the

level of TCRβC1 and TCRβC2, CD7, and CD52 and then transduced with a

lentivirus vector encoding a CAR that recognizes CD7; using this

procedure, were generated base-edited CAR7 (BE-CAR7) T-cell banks.[18]

Phase I of this study will involve the enrolment of 10 children with

refractory/relapsed T-ALL or other T-cell malignancies; these patients

received first lymphodepletion, followed by infusion of 0.2x106 to 2x106

CE-CAR7 T cells per Kg; patients in molecular remission at 28 days

underwent allo-HSCT, with consequent depletion of any persisting

BER-CAR7 cells by conditioning regimen used before HSCT.[18]

The results on the first 3 treated patients were recently reported: the

first patient, a 13-year-old girl with relapsing T-ALL after allo-HSCT,

had molecular remission after BE-CAR7 infusion and was then

transplanted with cells from her original donor, with successful

immunological reconstitution and ongoing leukemic remission; patient 2

developed fatal fungal complications; patient 3 achieved a molecular

remission following BE-CAR7 cell infusion and then underwent allo-HSCT

while in remission. Serious adverse events were observed in these

patients, including CRS, multilineage cytopenia, and opportunistic

infections.[18]

CD7 protein blockers.

A different method to block CD7 expression in T-lymphocytes consists of

the use of protein blockers that consist of single-chain variable

fragment and an intracellular retention domain, anchoring the targeted

antigen in the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus before its

proteolytic degradation. This technique can be used to downregulate CD7

expression in T-cells without CD7 gene editing.[19]

This technique can be used to generate functional and proliferating

CAR-T cells that do not express CD7 on their cell membrane.[20]

Wong et al., using this technique, have recently reported the

development of anti-CD7 CAR-T cells depleted of both CD7 and CD3

expression (PCART7), exhibiting potent cytotoxicity against T-ALL and

T-lymphoma cells.[21]

Zhang et al. have

developed a CD7 blockade strategy based on the use of tandem CD7

nanobody VHH6 coupled with an endoplasmic reticulum/Golgi-retention

motif to intracellularly block CD7 molecules, thus favoring their

degradation.[22] Preclinical studies have supported

the efficacy of CD7 blockade in preventing fratricide and the capacity

of CAR-T cells developed with this CD7 blocking strategy to exert a

potent cytotoxicity against CD7-positive leukemic cells.[20]

A phase I clinical trial with these CAR-T cells showed that 7/8 R/R

T-ALL and T-lymphoma patients achieved a CR after 3 months of CAR-T

cell infusion; 1 patient achieved an MRD-negative status, and one

patient with T-lymphoma achieved a CR for more than 12 months.[20] The majority of patients had only grade 1 or 2 CRS.[22]

Pan

et al. evaluated donor-derived CD7 CAR-T cells in the treatment of R/R

T-ALL. To minimize CD7 CAR-T cell-mediated fratricide, the authors have

generated a retroviral vector containing an anti-CD7, 4-1BB

costimulatory domain, and CD3 ζ signaling domain and a CD7-binding

domain fused with an endoplasmic reticulum retention signal sequence

enabling intracellular retention of CD7 molecules.[23]

In a phase I clinical trial, CD7 CAR-T cells manufactured from either

previous HSCT donors or new donors were administered to 20 R/R T-ALL

patients. 90% of patients achieved a CR, with seven patients proceeding

to HSCT at a median follow-up of 6.3 months, 15 patients remained in

remission. Grade 3-4 CRS occurred in 2 patients (10%) and grade I

neurotoxicity in three patients (15%); both side effects were not

correlated to T-cell donor type or dose level.[23]

More recently, an interim report from phase II of this trial was

presented, involving the enrolment of 20 R/R T-ALL patients, with a

median follow-up of 11.0 months.[24] 90% of patients

achieved a CR; 3 patients remained in remission, 7 relapsed, 2 died of

infection, and 8 patients proceeded to HSCT.[22] The 1-year PFS and OS rates were 62% and 60%, respectively.[24]

Patients without mediastinal mass had longer OS compared to those with

mediastinal mass.[24] Of 18 responders, seven had a relapse (three CD7+,

3 CD7- and one unknown.[24]

Recently, Tan and

coworkers reported the results of long-term (24-27 months) follow-up of

T-ALL patients included in the phase I study with CD7 CAR-T cells.[23]

After a median follow-up of 27 months, the ORR and CRR were 95% and

85%, respectively, with 35% of patients proceeding to HSCT; 6/20

patients had relapsed, and 4 of these 6 patients lost CD7 expression on

tumor cells.[25] After 24 months of follow-up, PFS and OS were 37% and 42%, with a median PFS and OS of 11 and 18.3 months, respectively.[25] (Table 1) Severe adverse events observed at >30 days after treatment included 5 infections and 1 grade 4 intestinal GvHD.[25]

Cytopenia occurred in all 20 patients within 30 days, while three

patients had late-onset grade 3 cytopenia at 8, 12.5, and 13 months

after infusion.

Non-relapse mortality occurred in five out of 20

patients (25%), mainly due to infections; in one case, it occurred for

engraftment syndrome in patients who received SCT consolidation. In all

patients, non-CAR CD7+ T and NK cells were cleared in 15 days after CD7

CAR-T cell infusion, remaining undetectable until the last follow-up in

all but one patient. In 2 patients, the long-term monitoring of T-cell

phenotype showed that the central memory T-cell compartment gradually

increased and that in one patient, low levels of naïve and

stem-cell-memory T-cell subpopulations were measurable.

CAR-T cells are generated with naturally CD7-negative T-cells or with CD7-negative CAR-T cells obtained by natural selection.

The generation of CAR-T cells from T-lymphocytes that do not express

CD7 antigen represents a potential alternative to CD7 gene elimination

or blocking. In this context, Freiwan and coworkers provided evidence

that naturally occurring CD7- T cells exist in healthy subjects and

represent functional effector T lymphocytes that can be used for CAR-T

cell generation.[26] These CD7- T cells represent 0.7-19% of T-lymphocytes and have mainly a CD4+ memory phenotype.[26]

CAR-T cells generated starting from these CD7- exhibited predominantly

a CD4+ memory phenotype and had significant antitumor activity upon

antigen exposure in vitro and in vivo in mouse xenograft models; importantly, these CAR-T cells bypass fratricide.[26]

Lu et al. described a different approach to obtaining CD7- CAR-T cells through a process of in vitro natural selection.[27]

Particularly, these authors have compared three different approaches to

generate CD7-targeted CAR-T cells and have evaluated their properties

in preclinical studies: NS7CAR T-cells generated first transducing

T-cells with a CD7-targeting vector and then subjected to a process of

natural selection during two weeks of cell culture; Neg7CAR T-cells

obtained transducing CD3+CD7- T lymphocytes with a CD7 targeting

vector; KO7CAR T-cells generated using T cells in which CD7 expression

was silenced by CRISPR/CAS9 gene editing.[27]

Compared with sorted CD7- CAR-T cells and CD7 knocked-out CAR-T cells,

NS7CAR T-cells displayed similar or superior therapeutic properties,

including a higher proportion of CD8+ memory T cells and a higher

proportion of CAR+ cells.[27] Using these NS7CAR

T-cells, a phase I clinical study was carried out in 14 patients with

R/R T-ALL and 6 with T-LBL; 19 of these patients achieved an MRD- CR in

the bone marrow and 5/9 achieved extramedullary CR.[27]

14 patients proceeded to allo-HSCT (10 consolidative, 4 salvage)

following NS7CAR-T cell therapy, with no relapses; of the 6 patients

not receiving allo-HSCT, 4 remained in CR at a median time of 54 days.[27] Only one patient experienced a grade 3 CRS.[27]

Zhang

and coworkers reported the results observed in 60 R/R T-ALL (35) and

T-LBL (25) treated with CD7 CAR-T cells NS7CAR at three different dose

levels: 5x105/Kg, 1-1.5x106/Kg and 2x106/Kg.[28]

After 28 days of treatment, 94% of patients achieved a CR in bone

marrow; in 32 patients with EMD, 78% displayed an objective response,

with 56% in CR and 22% in PR; the 2-yr OS and PFS were 63.5% and 53.7%,

respectively.[28] Importantly, PFS was significantly

better in 37 CR patients proceeding to consolidation HSCT compared to

10 patients who did not proceed to transplantation (67% vs 15%,

respectively); of the 10 patients without a transplant, 8 relapsed. No

differences were observed in OS and PFS in patients with or without

EMD, while patients with a previous history of transplantation showed a

trend toward a lower 1yr-OS rate (49.4% vs 77.6%).[28]

Patients with complex cytogenetics alterations demonstrated a

significantly reduced OS and PFS as compared to those patients without

these alterations (30% vs. 79% and 25% vs. 64.2%, respectively); in the

same way, patients carrying TP53 gene mutations showed a significant

lower OS (25% vs. 77.9%). The safety profile was acceptable, with grade

1-2 CRS in 80% and grade 3-4 in 11% of patients. Two patients (3.3%)

experienced grade I ICANS, and 1 (1.7%) experienced grade 4. CRS and

ICANS occurrence was not correlated with the proliferation of NS7CAR.

Thirty-seven patients (61.7%) demonstrated the occurrence of grade 3 or

higher cytopenia not recovered on or after day 30 post-infusion.[28]

Comparison of the efficacy of autologous and allogeneic CD7 CAR-T cells.

Zhang et al. have made a comparative analysis of autologous and

allogeneic CD7 CAR-T cells for the treatment of T-cell malignancies.

The study involved 10 patients with R/RT-ALL and T-LBL, 5 treated with

autologous CD7 CAR-T cells, and 5 with allogeneic CD7 CAR-T cells; the

CAR-T cells were Intrablock anti-CD7 CAR-T cells described by Pan et

al.[23] Although the very limited number of patients,

some comparisons between patients treated with auto and allo CD7 CAR-T

cells have been attempted: the CRR was higher for allo than for auto

(80% vs 40%, respectively); the relapse rate was higher in allo than in

auto patients (100% vs 25%, respectively); CAR-T cell survival in vivo was higher in allo than in auto patients.[29]

CAR-T cells developed with CD7 knockout associated with specific CAR-T cell integration.

Recently, Jiang and coworkers have evaluated in preclinical models the

efficacy of Elongation Factor 1α (EF1α)-driven CAR in which the CAR

vector was selectively inserted at the level of the disrupted CD7 locus

or of the TCR-alpha constant locus or at random integration sites using

a CAR retroviral vector.[30] EF1α-driven CAR

expressed at the CD7 locus enhances tumor rejection in a xenograft

model of T-ALL, suggesting possible clinical applications for this

CAR-T cell strategy.[30]

Alternative methods to avoid fratricide killing of CD7 CAR-T cells.

Recently, two alternative approaches have been proposed to avoid the

fratricide killing of CD7 CAR-T cells without implying genomic

manipulations. One approach proposed by Ye et al. was based on the

blocking of the CD7 antigen on the membrane of T-cells with a free

anti-CD7 monoclonal antibody containing the same binding domain as the

CAR during the preparation of CAR-T cells.[30] CAR-T

cells cultured with the anti-CD7 antibody displayed inhibition of

fratricide killing, improved cell viability, and were active in

mediating effective cytotoxicity against CD7-positive leukemic cells.[31]

The

other approach was based on the addition to CD7 CAR-T cells of

ibrutinib or dasatinib, pharmacologic inhibitors of key CAR/CD3ζ

signaling kinases, during in vitro expansion of these cells: the addition of these inhibitors rescued ex vivo expansion of unedited CD7 CAR-T cells regaining full CAR-T cell in vivo mediated cytotoxicity upon withdrawal of the inhibitors.[31] The CAR-T cells prepared using this methodology were shown to be suitable for cancer therapy purposes.[32]

CAR-T cell therapy of T-ALL based on CD5 targeting

In

addition to CD7, other membrane antigens expressed on normal, as well

as on leukemic T-lymphoid cells, are suitable targets of CAR-T cells.

One of these antigens is CD5; CD5 expression on normal cells is restricted to T-lymphocytes and B1 cells.

As observed for CD7, CD5 expression on CAR-T cells leads to fratricide of CD5 CAR-T cells.

Since

CD5 targeting with CAR-T cell therapy could be an attractive strategy

for the treatment of T-cell malignancies, several experimental studies

have characterized the properties of CAR-T cells engineered to target

CD5 antigen. Thus, Dai et al. reported the development of CD5 targeting

bi-epitopic CARs with fully human heavy-chain-only antigen recognition

domains; CAR-T cells generated in T-lymphocytes with CD5 knockout by

CRISPR/CAS9 gene editing were transduced with a lentiviral vector

encoding anti-CD5.[32] In preclinical models these CAR-T cells exert potent cytotoxicity against leukemic lymphoid T-cells.[33]

Ho

et al. have provided evidence that the affinity of CAR and cognate

antigen expression of CAR-T cells influence the intensity of CAR-T

fratricide.[33] Thus, it was shown that the

expression of a single chain fragment variable (scFv) with a

low-intensity of fratricide is induced in T-lymphocytes in which CD5

expression is downregulated, resulting in the generation of CAR-T cells

with maximized anti-CD25 effector activity.[34]

Another

recent study reported the development and the characterization of CAR-T

cells engineered to express anti-CD5 and anti-CD7 with fully human

heavy-chain-only domains and to mitigate fratricide by CD5 and CD7 gene

knockout using CRISPR/CAS9 gene editing.[34] These CD5/CD7 bispecific CAR-T cells displayed potent antitumor activity against T-cell malignancies.[35]

Few clinical studies have explored the safety and efficacy of CD5 CAR-T cells in T-cell malignancies.

In

2019, Hill et al. reported the results of a phase I dose-escalation

study (MAGENTA study) investigating autologous CD5-directed CAR-T cells

engineered to produce minimal and transient fratricide when expressed

in T-cells.[36] This treatment was considered as a

bridge to allogeneic HSCT. Nine patients were included in this study,

and 4 of these patients showed an objective response, with 3 CRs in an

angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma, a peripheral T-cell lymphoma, and a

T-ALL patient.[36] After infusion, there was a decrease in PB CD3+ cell

numbers, but there was no complete T-cell aplasia.

In 2021, the

same authors reported the results observed in an additional 9 patients

with R/R T-cell lymphomas treated with autologous CD5 CAR-T cells.[37]

Three of these four responding patients proceeded to HSCT, and two of

them remained alive and in CR for 29 and 24 months, respectively.[37]

Clinical response did not correlate with cell dose infused or degree of

T-cell expansion.

Pan et al. reported the initial results of a

phase I study involving the treatment of five patients who had

CD7-negative T-ALL relapsed after CD7 CAR-T cell therapy and received

prior HSCT donor-derived CD5 CAR-T cells; all these 5 patients achieved

a CR at day 30 and remained MRD-negative at a median follow-up of 27

months.[38] Although these results are promising, a

longer follow-up is required to assess the duration of response and the

reconstitution of a functional immune system.[38]

Patel and coworkers developed a new preparation of CD5 CAR-T cells, Senza 5TM,

an autologous CD5 CRSPR-CAS9 knockout anti-CD5 CAR-T product with high

specificity for CD5 targets; their strategy, with >90% of CD5 KO and

with >30% of CAR transduction, allowed the generation of two main

cell populations: one of CD5 KO CAR-T cells and the other of CD5KO

normal untransduced cells.[39] CD5 KO CAR-T5 cells

are expected to target CD5-positive T-leukemia/lymphoma cells but lead

to toxicity to normal T cells, which will be mitigated by the CD5 KO

normal T cells exhibiting a survival advantage after infusion.[38] Autologous Senza 5TM CART5 cells will be evaluated in CD5-positive T-cell lymphoma patients in a phase I clinical study.[39]

Chun

et al. initially reported the development of an anti-CD5 CAR-T cell

population in which CD5 expression was eliminated by CRISPR-CAS9 gene

editing: CRISPR-CASp KO of CD5 consistently enhances the antitumor

activity of CAR-T cells by increasing CAR-mediated activation and

proliferation.[40]

CD37 targeting with CAR-T cells for treatment of T-cell malignancies

CD37

is a transmembrane protein of the tetraspanin superfamily. A part of

T-cell lymphomas express CD37 on their cell membrane. Scarfs et al.

reported the development of CD37-targeting CAR-T cells (CAR37) with

4-1BB as a costimulatory domain. CAR-T cells demonstrated

antigen-specific activation, cytokine production, and cytotoxic

activity in models of peripheral T-cell lymphomas.[41] No significant fratricide-related events were observed in CAR-37 cells.[40]

To

date, the only ongoing trial involving CD37-directed CAR-T cells (NCT

04136275) involved the enrolment of CD37-positive hematological

malignancies, including leukemia, B-cell and T-cell lymphomas.[42]

In a preliminary phase I report, 4 patients were treated with CD37

CAR-T cells, including 1 patient with CTCL who achieved a CR on the 28th day post-infusion.[42]

CD70 targeting by CAR-T cells in T-cell lymphomas

CD70

is a type 2 transmembrane glycoprotein that is a member of the Tnf

ligand family. CD70 interacts with its ligand CD27. CD70 exhibits some

properties that make it a suitable therapeutic target in some

hematological malignancies: CD70 is only transiently expressed on

activated T- and B-cells, NK cells, and dendritic cells; CD70 is widely

expressed in some hematological malignancies, including some B-cell

lymphomas and systemic T-cell lymphomas; CD70 interaction with its

ligand CD27 induces a costimulatory signal in T and B lymphocyte

activation.

Targeting CD70 in CTCL using an antibody-drug

conjugate in patient-derived xenograft models resulted in marked

antitumor activity.[43]

The phase I COBAL-LYM

dose-escalation study evaluated allogeneic anti-CD70 CAR-T cells (CTX

130) in R/R patients with PTCL or CTCL.[44] CTX 130

cells are allogeneic T-lymphocytes modified with CRISPR/CAS9 gene

editing to abrogate expression of TCRα, MHC-I by β2-microglobulin

disruption and of CD70 and then transduced with a lentiviral vector

encoding anti-CD70.[44] 15 patients with T-cell

lymphomas were treated with CTX 130; responses were observed both in

PTCL (ORR 75%) and in CTCL (ORR 67%) patients; 29% of patients achieved

a CR.[44]

T-cell receptor targeting by CAR-T cells as a therapeutic strategy in T-lymphomas

Another

targeting strategy for T-cell malignancies is based on the eventual

exclusive expression of T-cell receptor-beta chain constant domains 1

and 2 (TRBC1 and TRBC2). Normal T-lymphocytes contain both TRBC1+ and TRBC2+ cell compartments, while T-cell malignancies are restricted to only one.[45] CAR-T cells targeting TRBC1 can recognize and kill normal and malignant TRBC1+ cells, sparing TRBC2+ T-cells.[45]

Recently,

the results of a phase I/II clinical study (AUTO4) involving the

treatment of 10 patients with R/R T-cell lymphomas with a

TRBC1-directed autologous CAR-T cell therapy, using four flat dose

levels.[46] 40% of patients achieved a CR. The most

common treatment-related adverse events were cytopenias (anemia and

neutropenia); however, 30% of patients had grade 3 or higher adverse

events, and PCR observed no CAR-T cell expansion.[46] With a longer follow-up, 50% of patients treated with the highest dose (450x106) maintained a complete metabolic response at 6 and 9 months, respectively.

CCR4 targeting in T-cell malignancies using CAR-T cell therapy

The

chemokine receptor CCR4 (also known as CD194) is a seven trans-membrane

G protein-coupled cell membrane molecule with selective expression on

cells of the hematopoietic system: particularly, CD4+CD25+Foxp3+

regulatory cells, TH2 and TH7 T cells predominantly express CCR4. CCR4

is highly expressed in many T-cell malignancies, including ATL, CTCL,

MF, and SS, and represents a biochemical therapeutic target for these

diseases. Thus, mogamulizumab, a defucosylated humanized antibody

engineered to exert enhanced antibody-dependent cytotoxicity that

targets CCR4, was approved for the treatment of R/R CTCL, MF, SS, and

ATLL.[47-48]

These observations have represented

a strong rationale for the development and evaluation of CAR-T cells

targeting CCR4. Thus, Perera et al. generated a lentiviral vector for

the genetic engineering of T cells to express a CAR that targets CCR4

using humanized variable heavy and kappa light chain derived from an

anti-human CCR4 antibody different from mogamulizumab.[49] CCR4-targeting CAR-T cells efficiently lysed patients-derived CTCL cell lines and exerted potent antitumor activity in vivo in a murine xenograft model of ATL[49].

Watanabe et al. have recently explored the development of CAR-T cells targeting CCR4: during the in vitro expansion of these cells, fratricide events specifically depleted Th2 and Tregs while sparing CD8+ and Th1 cells.[49]

At the end of the expansion process, a population of CAR-T cells with

potent antitumor efficacy against CCR4-expressing T-cell malignancies

is generated.[50]

CCR9 targeting in T-ALL

A

recent study showed that CCR9 is expressed in >70% of cases of

T-ALL, including >85% positivity in R/R patients, compared to a

scarce positivity (<5%) at the level of normal T-cells.[51] CAR-T cells targeting CCR9 are resistant to fratricide and have potent antileukemic activity both in vitro and in vivo, even at low antigenic density.[51]

These observations suggest that anti-CCR9 CAR-T cells could represent a

potentially promising treatment strategy for R/R T-ALLs.[51]

CD2 targeting CAR-T cell therapy

Xiang

et al. reported the development of an allogeneic “universal”

CD2-targeting CAR-T cells (UCART2), in which the CD2 antigen is deleted

to prevent fratricide, and the T-cell receptor is removed to prevent

GvHD; UCART2 cells exhibited marked efficacy against T-ALL and

prolonged the survival of T-ALL-engrafted immunodeficient mice.[52]

Treatment with rhIL-7-hyFc, a long-acting recombinant human IL-7,

prolonged UCART2 persistence and increased survival in primary patient

T-ALL model in vivo.[52]

According to these observations, it was suggested that allogeneic

fratricide-resistant UCART2, in combination with rhIL7-hyFc, could

represent a suitable approach for the treatment of T-ALL.

CD38 targeting CAR-T cell therapy

A recent study reported the preclinical activity of CAR-T cells targeting the CD38 antigen.[53]

CD38 antigen is a validated tumor antigen in multiple myeloma and in

T-ALL. CD38 expression on activated T cells did not impair CD38-CAR-T

cell expansion and in vitro function. In mice xenotransplanted with primary T-ALL cells, CD38-CAR-T cells mediated prolonged survival.[53]

Conclusions

CAR-T

cell therapy for T-cell malignancies is still in its infancy, and

additional studies are required before its introduction in the standard

treatment strategy for these diseases.

Several factors have

hampered the successful development of CAR-T cell technology in the

therapy of T-cell malignancies: (i) tumor contamination, related to the

admixture of manufactured CAR-T cell products with leukemic/lymphoma

T-cells; (ii) T cell aplasia as a consequence of the unwanted targeting

extended also to normal T cells; (iii) fratricide, a phenomenon related

to the cytotoxicity exerted by CAR-T cells not only targeting malignant

T cells but also other CAR-T cells expressing the target antigen.

Some

strategies have been developed to eliminate or mitigate some of these

limitations; thus, allogeneic CAR-T cells bypass the problem of CAR-T

cell contamination with tumor cells. On the other hand, various

strategies have been developed to mitigate fratricide, from gene

editing using either CRISPR-CAS9 technology or base editing to

intracell blocking or natural selection. However, some of these

strategies solve a problem, but at the same time raise other problems.

In

spite of these limitations, only some studies based on enough patients

with T-cell malignancies, with a follow-up of at least two years, have

provided initial encouraging results that need to be confirmed in

larger prospective studies.

Future studies have to clarify: (i)

the "optimal" membrane antigen to be targeted by CAR-T cells on the

surface of malignant T-cells; (ii) the comparative evaluation of auto-

and allo-CAR-T cells in terms of safety and efficacy; (iii) the role of

CAR-T cell therapy alone or as a bridge to allo-HSCT.

References

- Van der Zwet JCG, Cordo V, Cante-Barrett K,

Meijerink JPP. Multiomic approaches to improve outcome for T-cell acute

lymphoblastic leukemia patients. Adv Biol Reg 2019; 74: 100647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbior.2019.100647 PMid:31523030

- Liu

Y, Easton J, Shao Y, Maciaszek J, Wang Z, Wilkinson MR. The genomic

landscape of pediatric and young adult T-lineage acute lymphoblastic

leukemia. Nat Genet 2017; 49: 1211-1218. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3909 PMid:28671688 PMCid:PMC5535770

- Seki

M, Kimura S, Isobe T, Yoshida K, Ueno H, Nakajima-Takagi Y. Recurrent

SPI1 (PU1) fusions in high-risk pediatric T cell acute lymphoblastic

leukemia. Nat Genet 2017; 49: 1274-1281. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3900 PMid:28671687

- DuVall

AS, Sheade J, Anderson D, Yates SJ, Stock W. Updates in the management

of relapsed and refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia: an urgent plea

for new treatment in being answered. JCO Oncol Pract 2022; 18: 479-487.

https://doi.org/10.1200/OP.21.00843 PMid:35380890

- Stuver R, Moskowitz AJ. Therapeutic advances in relapsed and refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Cancer 2023, 15: 589. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15030589 PMid:36765544 PMCid:PMC9913081

- Liu

J, Zhang Y, Guo R, Zhao Y, Sun R, Guo S, Lu W, Zhao M. Targeted CD7 CAR

T-cells for treatment of T-lymphocte leukemia and lymphoma and acute

myeloid leukemia: recent advances. Fron Immunol 2023; 14: 1170968. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1170968 PMid:37215124 PMCid:PMC10196106

- Frankel

AE, Laver JH, Willigham MC, Burns LJ, Kersey JH, Vallera DA. Therapy of

patients with T-cell lymphomas and leukemias using an anti-CD7

monoclonal antibody-ricin a chain immunotoxin. Leukemia Lymphoma 1997;

26: 287-298. https://doi.org/10.3109/10428199709051778 PMid:9322891

- Gomes-Silva

D, Srinivasan M, Sharma S, Lee CM, Wagner DL, Davis TH. CD7-edited T

cells expressing a CD7-specific CAR for the therapy of T-cell

malignancies. Blood 2017; 130: 285-296. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2017-01-761320 PMid:28539325 PMCid:PMC5520470

- Depil

S, Duchhateau P, Grupp SA, Mufti G, Poirot L. "Off-the-shelf"

allogeneic CAR T cells: development and challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov

2020; 19: 185-199. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41573-019-0051-2 PMid:31900462

- Xie

L, Gu R, Yang X, Qiu S, Xu Y, Mou J, Wang Y, Xing H, Tang K, Tian Z, et

al. Universal anti-CD7 antigen on T/CAR-T cells. Blood 2022; 140

(suppl.1): 4535. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2022-158682

- Hu

Y, Zhou Y, Zhang M, Zhao H, Wiei G, Ge W, Cui Q, Mu Q, Chen G, Han L,

et al. Genetically modified CD7-targeting allogeneic CAR-T cell therapy

with enhanced efficacy for relapsed/refractory CD7-positive

hematological malignancies: a phase I clinical study. Cell Res 2022;

32: 995-1007. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41422-022-00721-y PMid:36151216 PMCid:PMC9652391

- Zhang

X, Zhou Y, Yang J, Li J, Qiu L, Ge W, Pei B, Chen J, Han L, Ren J, Lu

P. A novel universal CD7-targeted CAR-T cell therapy for relapsed or

refractory T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and T-cell lymphoblastic

lymphoma. Blood 2022; 140 (suppl.1): 4566-4567. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2022-165733

- Leedom

T, Hamil AS, Pouyanfard S, Govero J, Langland R, Ballard A, Schwarzkopf

L, Martens A, Espenchied A, Vinay P, et al. Characterization of

WU-CART-007, an allogeneic CD7-targeted CAR-T cell therapy for T-cell

malignancies. Blood 2021; 138 (suppl. 1): 703. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2021-153150

- Ghobadi

A, Aldoss I, Maudfe S, Wayne AS, Bhoywani D, Bajhel A, Dholaria B,

Faramand R, Mattison R, Rettig M, et al. Phase 1-2 dose-escalation

study of anti-CD7 allogeneic CAR-T cell in relapsed or refractory (R/R)

T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoblastic lymphoma (T-ALL/LBL).

HemaSphere 2023; 7 (s3): P356. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.HS9.0000968336.17893.02 PMCid:PMC10428339

- Li

S, Wang X, Yuan Z, Liu L, Luo L, Li Y, Wu K, Liu J, Yang C, Li Z, et

al. Eradication of T-ALL cells by CD7-targeted universal CAR-T cells

and initial test of ruxolitinib-based CRS management. Clin Cancer Res

2021; 27: 1242-1246. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-1271 PMid:33234511

- Li

S, Wang X, Liu L, Liu J, Rao J, Yuan Z, Gao L, Li Y, Lou L, Li G, et

al. CD7 targeted "off-the-shelf" CAR-T demonstrates robust in vivo

expansion and high efficacy in the treatment of patients with relapsed

and refractory T cell malignancies. Leukemia 2023; in press. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-2431426/v1

- Dioiorio

C, Murray R, Naniong M, Barrera L, Camblin A, Chukinas J, Coholan L,

Edwards A, Fuller T, Gonzalez C, et al. Cytosine base editing enables

quadruple-edited allogeneic CART cells for T-ALL. Blood 2022; 140:

619-629. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2022015825 PMid:35560156 PMCid:PMC9373016

- Chiesa

R, Georgiadis C, Syed F, Zhou H, Etuk A, Gkazi SA, Preece R, Ottaviano

G, Braybrook Y, Chu J, et al. Base-edited CAR7 T cells for relapsed

T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med 2023; 389: 899-910. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2300709 PMid:37314354

- Png

YT, Vinanica N, Kamiya T, Shimasaki N, Coustan-Smith N, Campana D.

Blockade of CD7 expression in T cells for effective chimeric antigen

receptor targeting of T-cell malignancies. Blood Adv 2017; 1:

1248-1260. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2017009928 PMid:29296885 PMCid:PMC5729624

- Kamiya

T, WONG D, Png YT, Campana D. A novel method to generate T-cell

receptor-deficient chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Blood Adv 2028;

2: 517-528. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2017012823 PMid:29507075 PMCid:PMC5851418

- Wong

XFA,Ng J, Zheng S, Ismail R, Qian H, Campana D. Development of an

off-the-Sh elf chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy for

T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) without gene editing. Blood

2022; 140 (suppl.1): 2358-2359. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2022-165822

- M,

Chen D Zhang, Fu X, Meng H, Nan F, Sun Z, Yu H, Zhang L, Li L, Li X, et

al. Autologous nanobody-derived fratricide-resistant CD7-CAR T-cell

therapy for patients with relapsed and refractory T-cell acute

lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res 2022; 28: 2830-2843. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-4097 PMid:35435984

- Pan

J, Tan Y, Wang G, Deng B, Ling Z, Song W, Seery S, Zhang Y, Peng S, Xu

J, et al. Donor-derived CD7 chimeric antigen receptor T cells for

T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: first-in-human, phase I trial. J

Clin Oncol 2021; 39: 3340-3351. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.21.00389 PMid:34324392

- Tan

Y, Pan J, Deng B, Ling Z, Weiliang S, Tian Z, Cao M, Xu J, Duan J, Wang

Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of donor-derived CD7 CART cells for r/r

T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma: interim analysis from a

phase 2 trial. Blood 2022; 140 (suppl. 1): 4602-4603. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2022-165819

- Tan

Y, Shan L, Zhao L, Deng B, Ling Z, Zhang Y, Peng S, Xu J, Duan J, Wang

Z, et al. Long-term follow-up of donor-derived CD7 CAR-T cell therapy

in patients with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Hematol Oncol

2023; 16: 34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-023-01427-3 PMid:37020231 PMCid:PMC10074659

- Freiwan

A, Zoine JT, Crawford JC, Vaidya A, Schattgen SA, Myers JA, Patil SL,

Khanlari M, Inaba H, Klco JM, et al. Engineering naturally occurring

CD7- T cells for the immunotherapy of hematological malignancies. Blood

2022; 140: 2684-2694. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2021015020 PMid:35914226 PMCid:PMC9935551

- Lu

P, Liu Y, Yang J, Zhang X, Yang X, Wang H, Wang L, Wang D, Jin D, Li J,

Huang X. Naturally selected CD7 CAR-T therapy without genetic

manipulations for T-ALL/LBL: first-in-human phase 1 clinical trial.

Blood 2022; 140: 321-334. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2021014498 PMid:35500125

- Zhang

X, Yang J, Li J, Qiu L, Zhang J, Lu Y, Zhao YL, Jin D, Li J, Lu P.

Analysis of 60 patients with relapsed or refractory T-cell acute

lymphoblastic leukemia and T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma treated with

CD7-targeted chimeric antigen receptor-T cell therapy. Am J Hematol.

2023 Dec;98(12):1898-1908. doi: 10.1002/ajh.27094. Epub 2023 Sep 23.

Erratum in: Am J Hematol. 2024 Jan 15; https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.27094 PMid:37740926

- Zhang

Y, Li C, Du M, Jiang H, Luo W, Tang L, Kang Y, Xu J, Wu Z, Wang X, et

al. Allogeneic and autologous anti-CD7 CAR-T cell therapies in relapsed

or refractory T-cell malignancies. Blood Cancer J 2023; 13: 61 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-023-00822-w PMid:37095094 PMCid:PMC10125858

- Jiang

J, Chen J, Liao C, Duan Y, Wang Y, Shang K, Huang Y, Tang Y, Gao X, Gu

Y, Sun J. Inserting EF1-drivem CD7-sepcific CAR at CD7 locus reduces

fratricide and enhances tumor rejection. Leukemia 2023; 37: 1660-1670. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-023-01948-3 PMid:37391486

- Yo

J, Jia Y, Tuhin IJ, Tan J, Monty MA, Xu N, Kang L, Li M, Lou X, Zhou M,

et al. Feasibility study of a novel preparation strategy for anti-CD7

CAR-T cells with a recombinant anti-CD7 blocking antibody. Mol Ther

Oncolyt 2022; 24: 719-728. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omto.2022.02.013 PMid:35317521 PMCid:PMC8913247

- Watanabe

N, Mo F, Zheng R, Ma R, Bray VC, van Leeuwen DG, Sritabal-Ramirez J, Hu

H, Wang S, Metha B, et al. Feasibility and preclinical efficacy of

CD7-medaited CD7 CAR T cells for T cell malignancies. Mol Ther 2023;

31: 24-34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2022.09.003 PMid:36086817 PMCid:PMC9840107

- Dai

Z, Mu W, Zhao Y, Jia X, Liu J, Wei Q, Tan T, Zhou J. The rational

development of CD5-targeting biepitopic CARs with fully human

heavy-chain-only antigen recognition domains. Mol Ther 2021; 29:

2707-2714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.07.001 PMid:34274536 PMCid:PMC8417515

- Ho

LY, Yu SR, Jeong JH, Lee HJ, Cho HJ, Kim HC. Mitigating the CD5 CAR-CD5

interaction enhances the functionality of CD5 CAR-t cells by

alleviating the T-cell fratricide. Cancer Res 2023; 83 (suppl. 7):

4086. https://doi.org/10.1158/1538-7445.AM2023-4086

- Dai

Z, Mu W, Zhao Y, Cheng J, Lin H, Ouyang K, Jia X, Liu J, Wei Q, Wang M,

et al. T cells expressing CD5/CD7 bispecific chimeric antigen receptors

with fully human heavy-chain-only domains mitigate tumor antigen

escape. Signal Transd Targeted Therapy 2022; 7: 85. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-022-00898-z PMid:35332132 PMCid:PMC8948246

- Hill

LC, Rouce RH, Smith TS, Yang L, Srinivasan M, Zhang H, Perconti S,

Mehta B, Dekhova O, Randall J, et al. Safety and anti-tumor activity of

CD5 CAR T-cells in patients with relapsed/refractory T-cell

malignancies. Blood 2019; 134 (suppl. 1): 199. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2019-129559

- Rouce

RH, Hill LC, Smith TS, Yang L, Boriskie B, Srinivasan M, Zhang H,

Perconti S, Mehta B, Dakhova O, et al. Early signals of anti-tumor

efficacy and safety with autologous CD5.CAR T-cells in patients with

refractory/relapsed T-cell lymphoma. Blood 2021; 138 (suppl.1): 654. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2021-154142

- Pan

J, Tan Y, Shan L, Deng B, Ling Z, Song W, Feng X, Hu G. Phase I study

of donor-derived CD5 CAR T cells in patients with relapsed or

refractory T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2022; 40:

7028. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2022.40.16_suppl.7028

- Patel

RP, Ghilardi G, Porazzi P, Yang S, Qian D, Pajarillo R, Wang M, Zhang

Y, Schuster SJ, Barta SK, et al. Clinical development of Senza 5TM

CART5: a novel dual population CD5 CRISPR-Cas9 knocked out anti-CD5

chimeric antigen receptor T cell product for relapsed and refractory

CD5+ nodal T-cell lymphoma. Blood 2022; 140 (suppl. 1): 1604-1605. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2022-166605

- Chun

I, Kim KH, Chiang YH, Xie W, Lee Y, Pajarillo R, Rotolo A, Shestova O,

Hong SJ, Abdel-Mohsen M, et al. CRISPR-Cas9 knock out of CD5 enhances

the anti-tumor activity of chiemeric antigen receptor T cells. Blood

2020; 136 (suppl.1): 51-52. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2020-136860

- Scarfò

I, Ormhoj M, Frigault MJ, Castano AP, Lorrey S, Bouffard AA, van Scoyk

A, Rodig SJ, Shay AJ, Aster JC, et al. Anti-CD37 chimeric antigen

receptor T cells are active against B- and T-cell lymphomas. Blood

2018; 132: 1495-1506. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2018-04-842708 PMid:30089630 PMCid:PMC6172564

- Frigault

MJ, Chen YB, Gallagher K, Horick NK, El-Jawahri A, Scarfò I, Wehrli M,

Huang L, Casey K, Cook D, et al. Phase 1 study of CD37-directed CAR T

cells in patients with relapsed or refractory CD37+ hematologic

malignancies. Blood 2021; 138 (suppl.1): 653. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2021-146236

- Wu

CH, Wang L, Yang CY, Wen KW, Hinds B, Gill R, McCormick F, Moasser M,

Pincus L, AI Wz. Targeting CD70 in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma using an

antibody-drug conjugate in patient-derived xenograft models. Blood Adv

2022; 6: 2290-2299. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2021005714 PMid:34872108 PMCid:PMC9006301

- Iyer

SP, Sica A, Ho J, Hu B, Zain J, Prica A, Weng WK, Kim YH, Kodadoust MS,

Palomba ML, et al. The cobalt-lym study of CTX 130: a phase 1

dose-escalation study of CD70-targeted allogeneic CRSPS-CAS9-engineered

CAR T cells in patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) T-cell

malignancies. HemaSphere 2022; 6: 53. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.HS9.0000843940.96598.e2

- Maciocia

PM, Wawrzyniecka PA, Philip B, Ricciardelli I, Akarca AU, Onuoha SC,

Legut M, Cole DK, Sewell AK, Gritti G, et al. Targeting the T cell

receptor -chain constant region for immunotherapy of T cell

malignancies. Nat Med 2017; 23: 1416-1423. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.4444 PMid:29131157

- Cwynarski

K, Iacoboni G, Thoulouili E, Menne T, Irvine D, Balasubramaniam N, Wood

L, Stephens C, Shang J, Xue E, et al. First in human study of AUTO4, a

TRBC1 targeting CAR T cell therapy in relapsed/refractory

TRBC1-positive peripheral T cell lymphoma. Blood 2022; 140 (suppl. 1):

10316-10317. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2022-165971

- Ureshino

H, Kamachi K, Kimura S. Mogamulizumab for the treatment of adult T-cell

leukemia/lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2019; 19: 326-331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clml.2019.03.004 PMid:30981611

- Moore

DC, Elmes JB, Shibu PA. Mogamulizumab: an anti-CC chemokine receptor 4

antibody for T-cell lymphomas. Ann Pharmacother 2020; 54: 371-379. https://doi.org/10.1177/1060028019884863 PMid:31648540

- Perera

LP, Zhang M, Nakagawa M, Petrus MN, Maeda M, Kadin ME, Waldmann TA,

Perera PY. Chimeric antigen receptor modified T cells that target

chemokine receptor CCR4 as a therapeutic modality for T-cell

malignancies. Am J Hematol 2017; 92: 892-901. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.24794 PMid:28543380 PMCid:PMC5546946

- Watanabe

K, Goemz AM, Kuramitsu S, Siurala M, Du T, Agarwal S, Song D, Scholler

J, Rotolo A, Posey AD, et al. Identifying highly active anti-CCR4 CAR T

cells for the treatment of T-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv 2023; 7:

3416-3430. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2022008327 PMid:37058474 PMCid:PMC10345856

- Maciocia

PM, Wawrzienecka PA, Maciocia nC. Burley A, Karpanasamy T, Devereaux S,

Heokx M, O'Connor D, Leon T, Rapoz-D'Silva T, et al. Anti-CCR9 chimeric

antigen receptor T cells for T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood

2022; 140: 25-37. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2021013648 PMid:35507686

- Xiang

J, Devenport JM, Carter AJ, Staser KW, Kim MY, O'Neal J, Ritchey JK,

Rettig MP, Gao F, Rettig G, et al. An "off-the-shelf" CD2 universal

CAR-T therapy for T-cell malignancies. Leukemia 2023; 37: 2448-2456. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-023-02039-z PMid:37798328 PMCid:PMC10681896

- Gilsovic-Aplenc

T, Diorio C, Chukinas JA, Veliz K, Shestova, Shen F, Nunez-Cruz S,

Vincent TL, Miao F, Milone MC, et al. CD38 as a pan-hematologic target

for chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Blood Adv 2023; 22: 4418-4430. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2022007059 PMid:37171449 PMCid:PMC10440474