Treatment for hard-to-treat anemias such as AA, myelodysplastic syndromes, and thalassemia can be achieved quickly, directly, and effectively with transfusion support of red blood cells and platelets.[7-9] Through blood transfusions, the use of antibiotics, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, or immunosuppressive medication, AA can reduce the emergence of anemia and thrombocytopenia-related symptoms, avoid severe infections and bleeding, and restore hematopoiesis.[9] On the other hand, patients' quality of life is negatively impacted by long-term blood transfusion assistance, and receiving platelets repeatedly can result in refractory platelets, which is linked to a bad prognosis for patients and a considerable rise in hospitalization expenses.[10,11] However, the effects of high-volume, long-term platelet transfusions on patients with AA are the only things that trials can currently show. The associations between platelet dynamic levels during transfusion therapy and curative treatment and the clinical results of AA remain unresolved, and little study has been done on the subject.

A well-developed analytical technique that may identify the quantity and features of individual trajectory clusters with comparable result progressions across time is the group-based trajectory model (GBTM). It has been extensively utilized in medical research and offers flexible and low-bias estimations of trajectory curves.[12] Thus, the goal of this study was to create a GBTM to investigate the clinical and demographic characteristics linked to each unique trajectory and to determine, for the first time, the correlation between diagnostic platelet level changes and survival rates in patients with AA. This approach aids in figuring out how trajectories and associated elements influence treatments that are motivated for further study.

Methods

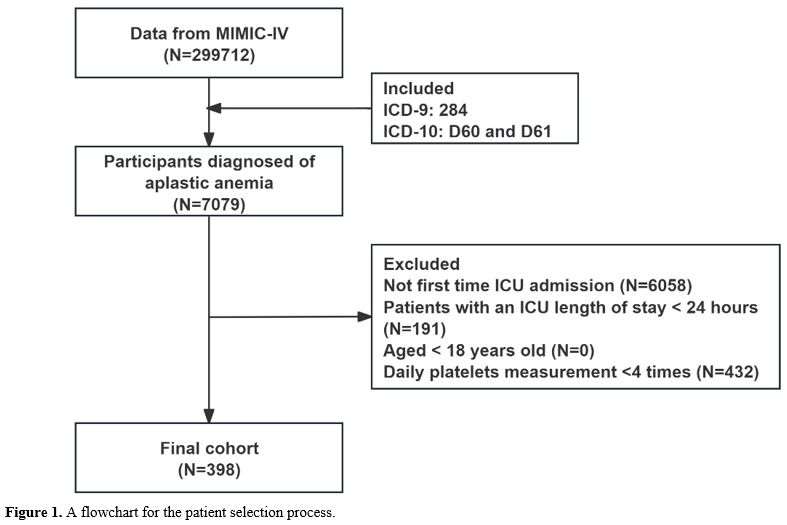

Data sources. The Institutional Review Board of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), Boston, Massachusetts, USA, developed the MIMIC-IV (Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care), from which the data were taken.[13] A major resource for studying critical care outcomes, predictive modeling, clinical decision support, and other research fields, MIMIC-IV is a publicly accessible critical care database that is well-known for its vast clinical data on patients treated in the intensive care unit (ICU). This data includes patient demographics, vital signs, medicines, laboratory measures, fluid balances, procedural and diagnostic codes, imaging reports, duration of stay, and fatalities (https://mimic.physionet.org/about/mimic/). MIT and BIDMC granted permission for this study to access the MIMIC-IV database.Patient selection. Clinical information for 299,712 ICU patients hospitalized between 2008 and 2019 is available in the MIMIC-IV database. Of these, 7,079 individuals had ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes (ICD-9: 284, ICD-10: D60 and D61) that indicated they had AA. We only included patients who were 18 years of age or older in our study, and we gathered information from their first ICU stay. Patients who had daily platelet measurement records less than 4 times, had non-first ICU admission and had ICU stays shorter than 24 hours were among the exclusion criteria. Consequently, the final analysis comprised 398 patients in total (Figure 1).

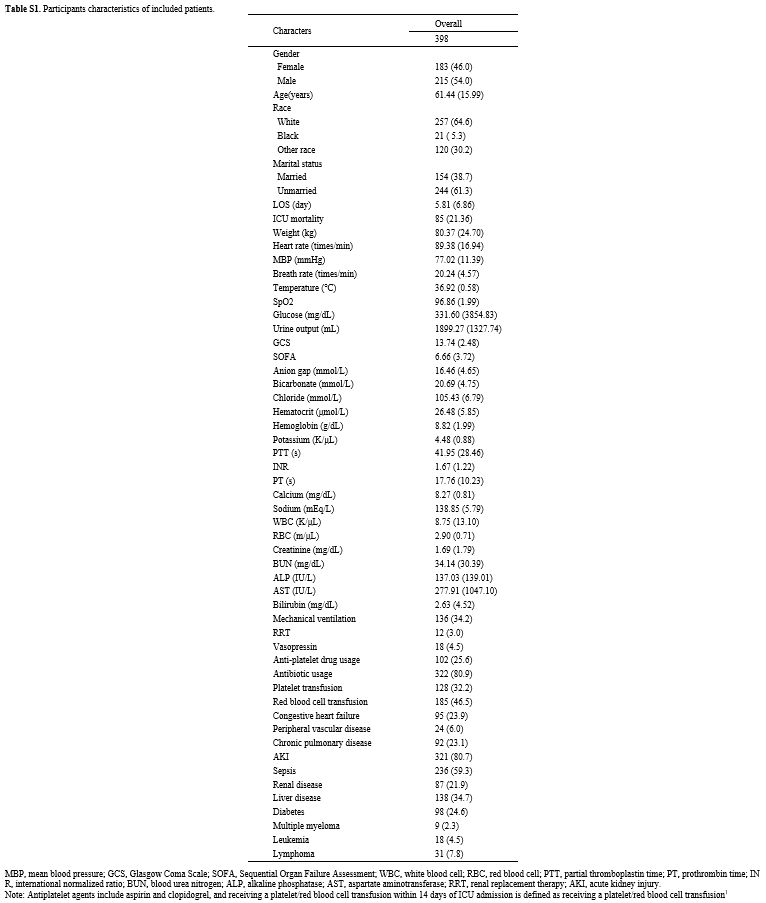

Variable collection. With the aid of Structured Query Language (SQL), all variables were taken out of the MIMIC-IV database. Vital signs, laboratory testing, demographics, clinical characteristics, and comorbidities are the five primary components of the extraction process. Only variables with missing proportions of less than 20% are considered for additional analysis. The 30-day ICU survival rate - which measures the amount of time from ICU admission to the study's conclusion - was the main result of this investigation. Throughout the first week following ICU admission, the daily platelet measurement values served as the independent variable. The measurement outcome should be the lowest platelet value obtained from a patient undergoing several platelet tests in a single day. Initial baseline characteristics and laboratory results measured within 48 hours of ICU admission were recorded and analyzed (Table S1).

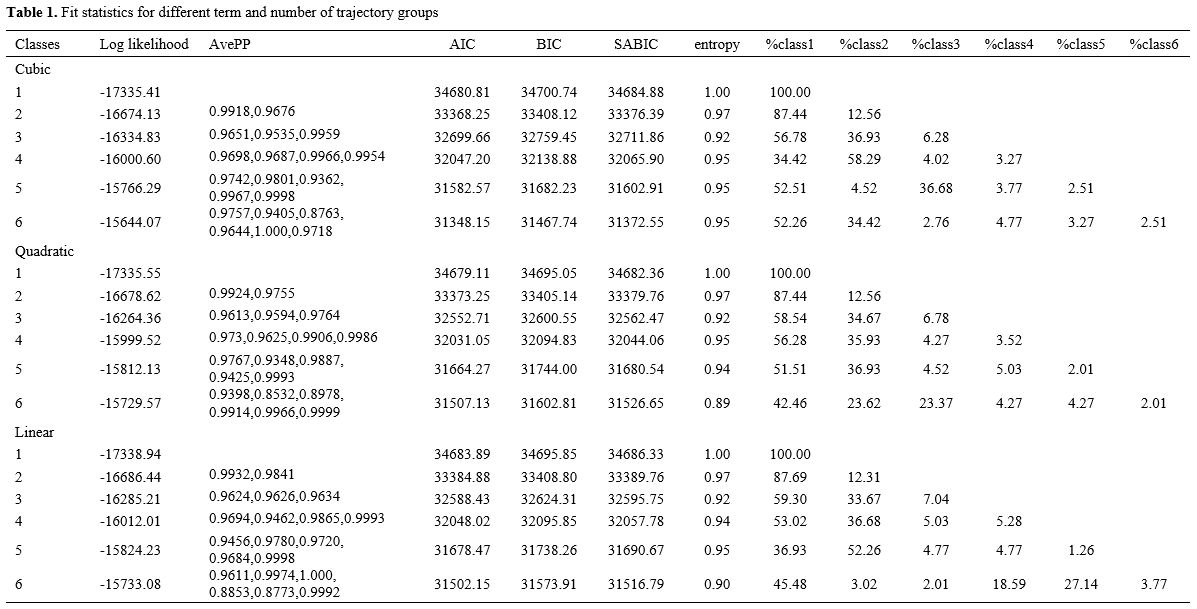

Platelet trajectory grouping. To convert diverse populations into homogenous groups with comparable trajectories, populations with similar developmental trajectories of platelet levels were identified using the Group-based Trajectory Model (GBTM) approach. Trajectories were identified and determined using GBTM and the ‘lcmm’ package. Patients were categorized into three groups using the GBTM approach according to platelet counts obtained during the first week of ICU hospitalization. The precise procedure is building a polynomial model devoid of variables to ascertain the number of groups. The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), the Sample-size adjusted BIC (SABIC), entropy, and the ratio of samples in each trajectory group to the overall sample were used to identify the best-fitting model.

Propensity score matching. The procedure of selecting patients for retrospective research has inherent constraints that might cause bias and introduce confounding variables. We performed Propensity Score Matching (PSM) analysis to reduce the influence of bias and confounding variables to solve these problems. Propensity scores are determined by PSM analysis by building a logistic regression model, which is subsequently utilized to match patients based on many characteristics. The variables used to calculate propensity scores include age, gender, race, marital status, length of stay (LOS), ICU mortality rate, heart rate, weight, mean systolic blood pressure (MBP), respiratory rate, temperature, peripheral blood oxygen saturation (SpO2), blood glucose, urine output, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA), anion gap (AG), bicarbonate, chloride, hematocrit, hemoglobin, potassium, partial thromboplastin time (PTT), international normalized ratio (INR), prothrombin time (PT), blood calcium, blood sodium, white blood cell count (WBC), red blood cell count (RBC), creatinine, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), aspartate transaminase (AST), bilirubin, mechanical ventilation, renal replacement therapy (RRT), antidiuretic hormone, antiplatelet drug use, antibiotic use, platelet transfusion, red blood cell transfusion, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, chronic lung disease, acute kidney injury (AKI), sepsis, kidney disease, liver disease, diabetes, multiple myeloma, leukemia, lymphoma. PSM analysis used a 1:1 nearest neighbor matching algorithm with a caliper of 0.1.

Statistical analysis. The Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test was utilized to evaluate the differences between groups, and continuous variables were displayed as the median (IQR). The chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables, which were shown as percentages (%). A two-sided P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The baseline table compared the differences in baseline characteristics among patients with different platelet trajectory groups. To examine the relationship between various trajectories and the 30-day survival status in AA patients, Kaplan-Meier (K-M) curves were created, adjusted for confounding variables, and used to evaluate the survival disparities across various groups. The survival status of AA patients was then assessed using K-M curves at various intervals following red blood cell and platelet transfusions between groups both before and after PSM. Cox proportional risk models were used to study groups with varying platelet trajectories to ascertain the impact of platelet levels on the 30-day survival status in patients with AA. In this work, R (Version 4.2.3) was used for data analysis after SQL was used to gather data from the MIMIC-IV (Version 2.2) database. The R packages included tableone, mice, glm, MatchIt, jskm, and survival. The `mice` package was used to impute missing values using the Random Forest (RF) method.

Result

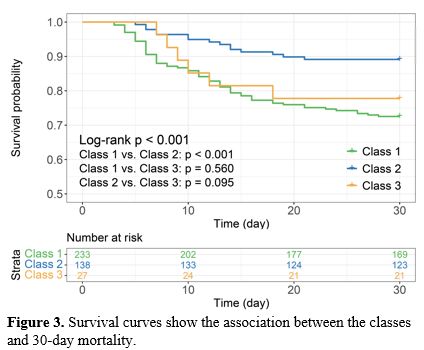

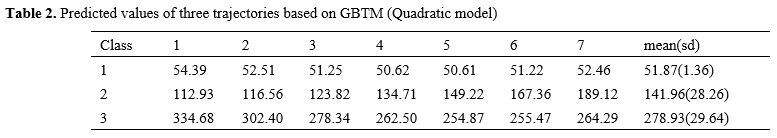

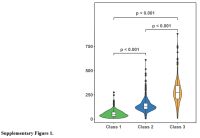

Characterization of platelet trajectories. Table 1 displays the model performance of GBTM trajectory modeling of platelet variations for 7 days following ICU admission. We integrated many criteria, including AIC, BIC, and SABIC, and conducted multiple fits on the polynomial. For the following analysis, we employed a quadratic model with three groups, Class 1, Class 2, and Class 3, accounting for 58.54%, 34.67%, and 6.78%, respectively.Figure 2 and Table 2 display the platelet changes throughout one week. Class 1 kept its low platelet count steady. Platelet counts in Class 2 indicated an upward trend. Class 3 started with a higher baseline platelet count, followed by a decrease and then an increase with significant fluctuations. The platelet counts of the various groups varied significantly (P<0.001, Figure S1).

|

Figure 2. Three trajectories of the platelets based on GBTM. Shaded parts represent 95% CI, and the solid lines represent predicted values. |

|

Table 2. Predicted values of three trajectories based on GBTM (Quadratic model). |

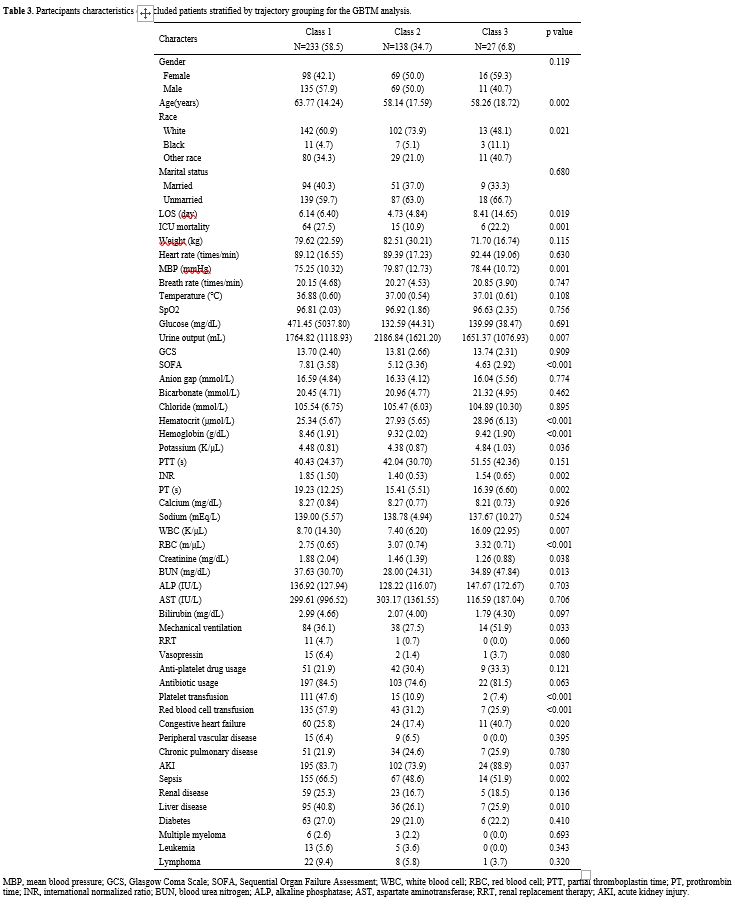

Basic characteristics of trajectory grouping. Table 3 displays clinical features and population demographics categorized by platelet trajectory. The differential analysis results of the three trajectory groups showed that the Class 1 group had significantly higher age, ICU mortality rate, SOFA score, INR, PT, creatinine, BUN, platelet transfusion ratio, red blood cell transfusion ratio, as well as proportions of sepsis and liver disease compared to the other two groups (P<0.05), while MBP, hematocrit, hemoglobin, and RBC count were significantly lower (P<0.05). Additionally, patients in Class 3 had significantly higher LOS, WBC, and potassium levels (P<0.05). In terms of urine output, the highest value was in Class 2, at 2186.84±1621.20 mL.

|

|

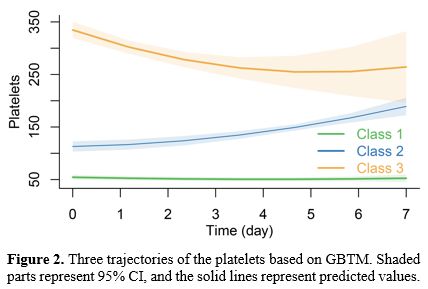

Platelet trajectories and survival rates. Figure 3 displays the 30-day survival status Kaplan-Meier curve for AA patients in various classes. It showed substantial variations in the 30-day survival rates across the trajectory groups, with Class 2 patients having the greatest survival rate (Log-rank P<0.001). Except for Class 1 and Class 2 (Log-rank P<0.001), there was no significant difference in the comparison between any of the two groups (Log-rank P>0.05) (Figure 3).

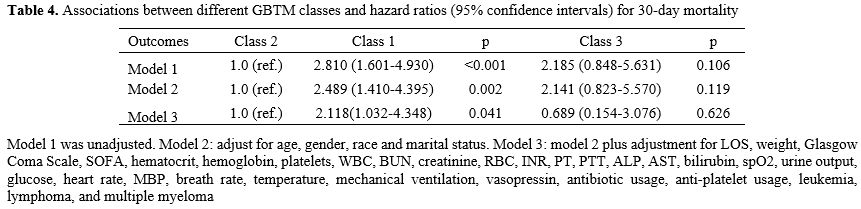

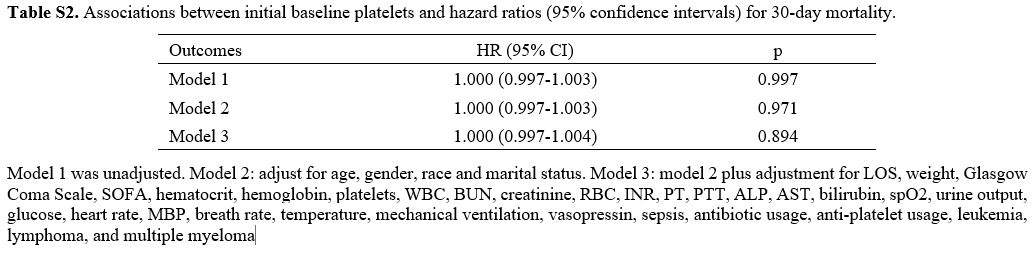

Cox proportional hazards regression analysis of platelet trajectories and 30-day survival status of AA patients. Cox models were built based on baseline platelet levels and various groups of platelets GBTM to investigate the relationship between platelet trajectories and the 30-day survival status of AA patients. The 30-day survival status of AA patients did not significantly correlate with baseline platelet counts, according to the data (P>0.05, Table S2). The GBTM results showed that Class 1 with stable low platelets had a considerably higher prognosis risk than Class 2 with continually increasing platelets. This link persisted even after adjusting for confounding variables (P<0.05, Table 4).

|

|

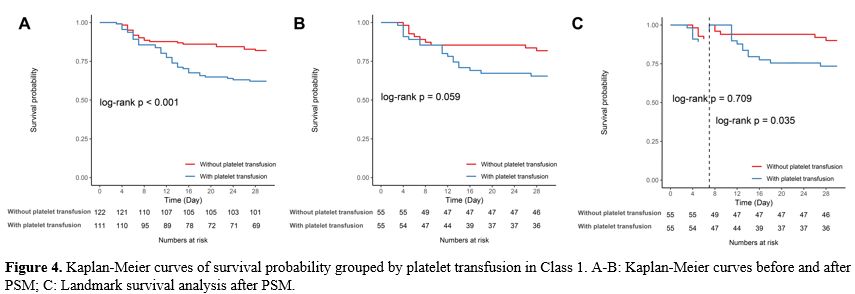

The impact of platelet transfusion before and after PSM on the 30-day survival rate of AA patients. We also looked at how platelet transfusion affected patients in the lower platelet group (Class 1) in terms of their 30-day survival status (Figure 4). Long-term platelet transfusion significantly impacted patient survival in the original model prior to PSM, and this was linked to a decline in the survival rate of AA patients (log-rank P<0.001, Figure 4A). However, after using PSM to account for confounding factors, the significance vanished (log-rank P=0.059, Figure 4B). Platelet transfusion did not increase the survival of patients with low platelet counts (Class 1 group), and it may have a negative long-term impact on their survival, according to landmark analysis (log-rank P=0.035, Figure 4C).

|

|

Discussion

Patients with AA had their platelet counts monitored throughout time, and the findings of these measurements were used to stratify the patients into three groups. It was discovered that a higher 30-day survival rate was related to the platelet levels in the Class 2 group of AA patients. Following PSM adjustment, the data revealed that platelet transfusion had no significant benefits for survival in the group of AA patients with low platelet levels (Class 1), and it may even be detrimental to long-term survival.AA is a rare autoimmune-mediated life-threatening bone marrow disease, primarily classified into congenital and acquired forms. The main pathogenic mechanisms of acquired AA involve abnormal activation of T lymphocytes and hyperfunction of bone marrow damage, leading to marrow destruction.[14,15] This destruction is mediated by cytotoxic T cells, which target hematopoietic cells and hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) through autoimmune attacks. By secreting perforin and granzyme B to create pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interferon (IFN)-γ, tumor necrosis factor α, and through the Fas/Fas ligand pathway, activated cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) kill hematopoietic stem cells (HSPCs) and limit the development of blood cells and immune cells in adult hematopoiesis.[14,16] The length of leukocyte telomeres resembles that of other somatic cells and is linked to the risk of illness associated with decreased cell proliferation and tissue deterioration.[17] Telomeres are DNA components that are entangled with cell division. The naturally occurring enzyme telomerase helps to protect telomere length to some degree. However, mutations in telomerase components can result in inadequate telomere maintenance in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), which can lead to bone marrow hypoplasia and premature HSC depletion.[18] In acquired AA, telomere shortening may be a marker of bone marrow damage. Before allogeneic HSC transplantation, almost one-fifth of AA patients were found to have shorter telomere lengths, which is linked to the severity of AA, the risk of recurrence, and overall survival.[19] This study did not analyze telomere length; therefore, we suggest that future research could further explore the role of telomere length in the etiology of AA, particularly in the context of distinguishing between acquired and congenital AA.

Survival was highest in the Class 2 trajectory group, which had a consistent trend of increasing platelet levels over a range of levels, compared with the other two trajectory groups. As components of bone marrow cells, platelet count and erythrocyte count are major predictors of peripheral blood stem cell mobilization in healthy donors and play a key role in physiological hemostasis and thrombosis.[20,21] Surprisingly, we found that platelet transfusion did not provide additional survival benefits for AA patients with low platelet levels and even harmed long-term outcomes. In clinical practice, platelet transfusion is a routine supportive therapy used to treat bleeding and thrombocytopenia following hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT) in accordance with pre-conditioning regimens.[22] However, it is not long-term successful. Repetitive exposure to platelets can trigger alloimmune responses against Human Leukocyte Antigens (HLA) or Human Platelet-specific Alloantigens (HPA), and that can result in the generation of antiplatelet antibodies causing refractoriness to donor platelets or post-transfusion purpura, linked to transplant failure after HSCT. Ultimately, this can impact the course of therapy and clinical outcomes.[23-25]

In this study, the results indicated that for AA patients in the Class 1 trajectory group - specifically those with persistently low platelet levels - platelet transfusion did not improve their 30-day survival rates, suggesting that platelet transfusion may not be an effective strategy for improving survival in this particular patient population. However, this does not imply that platelet transfusion lacks value in all cases. In other patient groups, platelet transfusion may still be necessary to reduce bleeding risk and improve clinical symptoms.[26] Therefore, this study recommends that clinicians develop individualized treatment plans for AA patients considering platelet transfusion tailored to the specific circumstances and platelet trajectory of each patient. The findings also emphasize the importance of considering the dynamic changes in platelet levels in AA treatment and indicate that future research should further explore the benefits of platelet transfusion in different patient populations.

It is clear where we fall short. This study cannot describe the link between AA patients and changes in platelet level trajectories since it is retrospective and has inherent biases. In contrast, prospective studies achieve this goal. More extensive, multicenter prospective trials are therefore required. Secondly, even though selection bias was minimized by PSM analysis, data bias cannot be eliminated due to the extended duration. Third, the absence of markers for hematopoietic function prevented us from determining the severity of AA. Fourth, this study primarily focused on platelet levels, which may not fully capture the complexity of AA patient conditions. Other hematological parameters, such as neutrophil counts, are also important factors in assessing the severity and prognosis of AA. We recommend that future research further explore the role of neutrophil counts and other hematological parameters in the prognosis of AA patients, as well as their interactions with changes in platelet levels. Lastly, our model is based on the MIMIC-IV database, which mostly includes patients from the United States. The study's findings' applicability to the world's population is thus yet uncertain.

Conclusions

Our study identified three different trajectory patterns of platelet levels in AA patients. The increase in platelet levels during hospitalization was associated with improved survival in AA patients. For AA patients who have consistently low platelet levels, platelet transfusion may not be an effective strategy for improving survival rates in this population.Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval and consent to participate. The dataset is a derivative of MIMIC-IV, and thus, no new patient data was collected. Its ethical approval follows that of the parent MIMIC dataset.Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.Authors' contributions

All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting and revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.References

- Moore, C. A.; Krishnan, K. Aplastic Anemia. In StatPearls, 2024.

- Red

Blood Cell Disease Group, C. S. o. H. C. M. A. [Chinese expert

consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of aplastic anemia (2017)].

Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi 2017, 38 (1), 1-5. DOI:

10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-2727.2017.01.001 From NLM PubMed-not-MEDLINE.

- Vaht,

K.; Goransson, M.; Carlson, K.; Isaksson, C.; Lenhoff, S.; Sandstedt,

A.; Uggla, B.; Winiarski, J.; Ljungman, P.; Brune, M.; et al. Incidence

and outcome of acquired aplastic anemia: real-world data from patients

diagnosed in Sweden from 2000-2011. Haematologica 2017, 102 (10),

1683-1690. DOI: 10.3324/haematol.2017.169862 From NLM Medline. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2017.169862 PMid:28751565 PMCid:PMC5622852

- Vallejo,

C.; Rosell, A.; Xicoy, B.; Garcia, C.; Albo, C.; Polo, M.; Jarque, I.;

Esteban, B.; Codesido, M. L. A multicentre ambispective observational

study into the incidence and clinical management of aplastic anaemia in

Spain (IMAS study). Ann Hematol 2024, 103 (3), 705-713. DOI:

10.1007/s00277-023-05602-x From NLM Medline. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-023-05602-x PMid:38175253

- Rajput,

R. V.; Shah, V.; Shalhoub, R. N.; West-Mitchell, K.; Cha, N. R.;

Conry-Cantilena, C.; Leitman, S. F.; Young, D. J.; Wells, B.; Aue, G.;

et al. Granulocyte transfusions in severe aplastic anemia.

Haematologica 2024, 109 (6), 1792-1799. DOI:

10.3324/haematol.2023.283826 From NLM Medline. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2023.283826 PMid:38058170 PMCid:PMC11141686

- Nakamura,

R.; Patel, B. A.; Kim, S.; Wong, F. L.; Armenian, S. H.; Groarke, E.

M.; Keesler, D. A.; Hebert, K. M.; Heim, M.; Eapen, M.; et al.

Conditional survival and standardized mortality ratios of patients with

severe aplastic anemia surviving at least one year after hematopoietic

cell transplantation or immunosuppressive therapy. Haematologica 2023,

108 (12), 3298-3307. DOI: 10.3324/haematol.2023.282781 From NLM

Medline. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2023.282781 PMid:37259612 PMCid:PMC10690917

- Guarente,

J.; Tormey, C. Transfusion Support of Patients with Myelodysplastic

Syndromes. Clin Lab Med 2023, 43 (4), 669-683. DOI:

10.1016/j.cll.2023.07.002 From NLM Medline. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cll.2023.07.002 PMid:37865510

- Kuriri,

F. A.; Ahmed, A.; Alanazi, F.; Alhumud, F.; Ageeli Hakami, M.;

Atiatalla Babiker Ahmed, O. Red Blood Cell Alloimmunization and

Autoimmunization in Blood Transfusion-Dependent Sickle Cell Disease and

beta-Thalassemia Patients in Al-Ahsa Region, Saudi Arabia. Anemia 2023,

2023, 3239960. DOI: 10.1155/2023/3239960 From NLM PubMed-not-MEDLINE. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/3239960 PMid:37152479 PMCid:PMC10162868

- Kulasekararaj,

A.; Cavenagh, J.; Dokal, I.; Foukaneli, T.; Gandhi, S.; Garg, M.;

Griffin, M.; Hillmen, P.; Ireland, R.; Killick, S.; et al. Guidelines

for the diagnosis and management of adult aplastic anaemia: A British

Society for Haematology Guideline. Br J Haematol 2024, 204 (3),

784-804. DOI: 10.1111/bjh.19236 From NLM Medline. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.19236 PMid:38247114

- Song,

X.; Qi, J.; Li, X.; Zhou, M.; He, J.; Chu, T.; Han, Y. Exploration of

risk factors of platelet transfusion refractoriness and its impact on

the prognosis of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a

retrospective study of patients with hematological diseases. Platelets

2023, 34 (1), 2229905. DOI: 10.1080/09537104.2023.2229905 From NLM

Medline. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537104.2023.2229905 PMid:37409458

- Mastrorilli,

G.; Fiorentino, F.; Tucci, C.; Lombardi, G.; Aghemo, A.; Colombo, G. L.

Cost Analysis of Platelet Transfusion in Italy for Patients with

Chronic Liver Disease and Associated Thrombocytopenia Undergoing

Elective Procedures. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res 2022, 14, 205-220. DOI:

10.2147/CEOR.S354470 From NLM PubMed-not-MEDLINE. https://doi.org/10.2147/CEOR.S354470 PMid:35422645 PMCid:PMC9005228

- Nagin,

D. S. Group-based trajectory modeling: an overview. Ann Nutr Metab

2014, 65 (2-3), 205-210. DOI: 10.1159/000360229 From NLM Medline. https://doi.org/10.1159/000360229 PMid:25413659

- Johnson,

A. E. W.; Bulgarelli, L.; Shen, L.; Gayles, A.; Shammout, A.; Horng,

S.; Pollard, T. J.; Hao, S.; Moody, B.; Gow, B.; et al. MIMIC-IV, a

freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Sci Data 2023, 10

(1), 1. DOI: 10.1038/s41597-022-01899-x From NLM Medline. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01899-x PMid:36596836 PMCid:PMC9810617

- Pan,

P.; Chen, C.; Hong, J.; Gu, Y. Autoimmune pathogenesis,

immunosuppressive therapy and pharmacological mechanism in aplastic

anemia. Int Immunopharmacol 2023, 117, 110036. DOI:

10.1016/j.intimp.2023.110036 From NLM Medline. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2023.110036 PMid:36940553

- Fattizzo,

B.; Motta, I. Rise of the planet of rare anemias: An update on emerging

treatment strategies. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022, 9, 1097426. DOI:

10.3389/fmed.2022.1097426 From NLM PubMed-not-MEDLINE. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.1097426 PMid:36698833 PMCid:PMC9868867

- Giudice,

V.; Selleri, C. Aplastic anemia: Pathophysiology. Semin Hematol 2022,

59 (1), 13-20. DOI: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2021.12.002 From NLM

Medline. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.seminhematol.2021.12.002 PMid:35491054

- Lansdorp,

P. Telomere Length Regulation. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 943622. DOI:

10.3389/fonc.2022.943622 From NLM PubMed-not-MEDLINE. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.943622 PMid:35860550 PMCid:PMC9289283

- Carvalho,

V. S.; Gomes, W. R.; Calado, R. T. Recent advances in understanding

telomere diseases. Fac Rev 2022, 11, 31. DOI: 10.12703/r/11-31 From NLM

PubMed-not-MEDLINE. https://doi.org/10.12703/r/11-31 PMid:36311538 PMCid:PMC9586155

- Wang,

Y.; McReynolds, L. J.; Dagnall, C.; Katki, H. A.; Spellman, S. R.;

Wang, T.; Hicks, B.; Freedman, N. D.; Jones, K.; Lee, S. J.; et al.

Pre-transplant short telomeres are associated with high mortality risk

after unrelated donor haematopoietic cell transplant for severe

aplastic anaemia. Br J Haematol 2020, 188 (2), 309-316. DOI:

10.1111/bjh.16153 From NLM Medline. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.16153 PMid:31426123 PMCid:PMC6980174

- Furst,

D.; Hauber, D.; Reinhardt, P.; Schauwecker, P.; Bunjes, D.; Schulz, A.;

Mytilineos, J.; Wiesneth, M.; Schrezenmeier, H.; Korper, S. Gender,

cholinesterase, platelet count and red cell count are main predictors

of peripheral blood stem cell mobilization in healthy donors. Vox Sang

2019, 114 (3), 275-282. DOI: 10.1111/vox.12754 From NLM Medline. https://doi.org/10.1111/vox.12754 PMid:30873634

- Opneja,

A.; Kapoor, S.; Stavrou, E. X. Contribution of platelets, the

coagulation and fibrinolytic systems to cutaneous wound healing. Thromb

Res 2019, 179, 56-63. DOI: 10.1016/j.thromres.2019.05.001 From NLM

Medline. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2019.05.001 PMid:31078121 PMCid:PMC6556139

- von

Kries, R.; Shearer, M.; McCarthy, P. T.; Haug, M.; Harzer, G.; Gobel,

U. Vitamin K1 content of maternal milk: influence of the stage of

lactation, lipid composition, and vitamin K1 supplements given to the

mother. Pediatr Res 1987, 22 (5), 513-517. DOI:

10.1203/00006450-198711000-00007 From NLM Medline. https://doi.org/10.1203/00006450-198711000-00007 PMid:3684378

- Saris, A.; Pavenski, K. Human Leukocyte Antigen Alloimmunization and Alloimmune Platelet Refractoriness. Transfus Med Rev 2020, 34 (4), 250-257. DOI: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2020.09.010 From NLM Medline. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmrv.2020.09.010 PMid:33127210

- Hawkins,

J.; Aster, R. H.; Curtis, B. R. Post-Transfusion Purpura: Current

Perspectives. J Blood Med 2019, 10, 405-415. DOI: 10.2147/JBM.S189176

From NLM PubMed-not-MEDLINE. https://doi.org/10.2147/JBM.S189176 PMid:31849555 PMCid:PMC6910090

- Vassallo,

R. R.; Norris, P. J. Can we "terminate" alloimmune platelet transfusion

refractoriness? Transfusion 2016, 56 (1), 19-22. DOI: 10.1111/trf.13411

From NLM Medline. https://doi.org/10.1111/trf.13411 PMid:26756708

- Anthon, C. T.; Granholm, A.; Sivapalan, P.; Zellweger, N.; Pene, F.; Puxty, K.; Perner, A.; Moller, M. H.; Russell, L. Prophylactic platelet transfusions versus no prophylaxis in hospitalized patients with thrombocytopenia: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Transfusion 2022, 62 (10), 2117-2136. DOI: 10.1111/trf.17064 From NLM Medline. https://doi.org/10.1111/trf.17064 PMid:35986657 PMCid:PMC9805167

Supplementary Files

|

Supplementary Figure 1 |

|

Table S1. Participants characteristics of included patients. |

|

Table S2. Associations between initial baseline platelets and hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) for 30-day mortality. |