Cutaneous involvement in hematologic malignancies, especially in leukemia, generally carries an unfavorable prognosis,[2] but opinions are conflicting.[3,4]

Commonly observed in chronic lymphocytic leukemia[1] and chronic myeloid leukemia (4-27%),[5] it is the most frequent extramedullary localization in AML and considered a sanctuary for leukemic cells, it occurs in 3-6% of acute myeloid leukemia (AML); but some reports show an incidence of up to 50% in myelomonocytic and monocytic types.[6,7] When associated with AML, LC is typically managed according to standard protocols; however, the efficacy of novel agents in this specific patient population remains largely unknown.

Herein, we report a case of a 58-years-old female patient with AML who was admitted to our Hospital in January 2024 because of skin lesions consistent with leukemic infiltrates and was consequently treated with Azacitidine plus Venetoclax (AZA-VEN).

Case Presentation

In January 2024, a 58-year-old female patient underwent a hematological examination because of cutaneous nodules previously biopsied at another center whose histopathological findings were consistent with leukemic infiltrates. The lesions primarily appeared on the arms and then spread extensively to the chest area. The patient reported no constitutional symptoms (e.g., fever, night sweats, or weight loss). Medical history was remarkable for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) due to a 30-year smoking habit requiring triple inhalation therapy. Furthermore, she was previously affected by De Quervain disease, for which she underwent surgery. Physical examination revealed generalized violaceous and hard nodules on the entire body except the face (Figure 1). Laboratory tests showed a reduced leukocyte count (WBC = 2.92x106/L), normal platelet (PLT) count (264x109/L) and hemoglobin (Hb) level (12.2 g/dl), a prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time of 50.9 sec and elevated D-dimer (>20.000 ng/ml), low level of fibrinogen (89 mg/dl), and elevated lactate dehydrogenase (1054 U/L). Total Body Computed Tomography scan showed no involvement of other organs, whereas pulmonary function testing was consistent with a very severe COPD.The bone marrow (BM) morphologic examination revealed a 70% blast infiltrate. Flow cytometry (FCM) evaluation resulted in the following pattern: CD45+, CD34-, CD33+, CD117-, CD13+, CD56+, CD15+, CD64+, MPO+, CD4+. The molecular genetic analysis revealed mutations in nucleophosmin1 (NPM1) and isocitrate dehydrogenase1 (IDH1) genes. Cytogenetics analysis failed because of the absence of metaphases in the examined sample, and FISH showed no aberrations involving chromosomes 5, 7, 8, 11, and 20. To exclude a possible central nervous system (CNS) involvement, we performed a lumbar puncture and then examined cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) using conventional cytology and FCM, both of which resulted in negative.

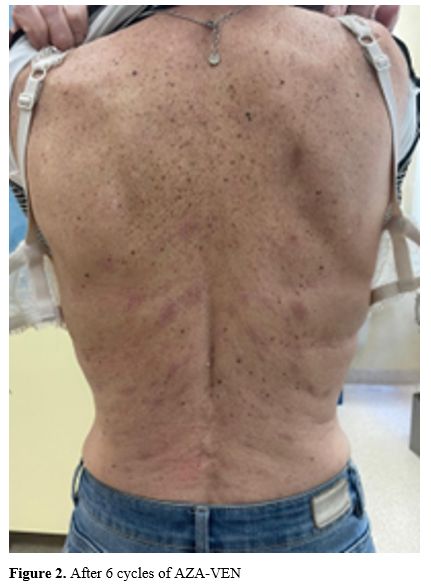

According to the AML-Composite Model (AML-CM),[8] the patient was considered unsuitable for intensive chemotherapy (IC); hence, she received treatment with Azacytidine (given at 75 mg/m2 intravenously on days 1-7) plus Venetoclax (given at 100 mg on day 1, 200 mg on day 2 and 400 mg on day 3-28). At the end of the first cycle, the patient showed a peripheral hematologic recovery (WBC 1.79x106/L, neutrophils 1.03x106/L; Hb 8.9 g/dl, PLT 330x109/L). Concomitant to the hematologic recovery, the skin lesions were reduced in size, number, and consistency. BM examination demonstrated a complete morphological remission (CR). At this stage, the NPM1 copy number was 123.2333/10.000 of ABL in BM and 24.876/10.000 of ABL in the peripheral blood. The therapy was continued, and by cycle no. 6, a complete resolution of the skin lesions was achieved with a persistent condition of BM morphologic CR and positive, measurable residual disease (MRD) (Figure 2). No temporary or permanent interruptions due to toxicity were reported. Since LC is prone to be associated with CNS infiltration and little is known about the attitude of VEN to cross the blood-brain barrier, we decided on a monthly schedule of medicated lumbar punctures. The patient is still alive at eleven months from therapy starting, in MRD positive CR, and receiving her IX cycle.

Discussion

The recommended treatment for patients with AML and LC is conventional IC followed by a consolidation program defined according to NCCN or ELN risk allocation.[9] In this context, skin infiltration is not recognized as having a specific prognostic role. Some have reported approaches for LC like modulatory therapy,[10] radiotherapy,[11] and total skin electron beam.[12]The therapeutic decision is usually determined by factors such as age, performance status, cytogenetics, and molecular markers,[13] but it is also essential to consider the patient's comorbidities. To decide the best treatment, the use of AML-CM, a risk-stratifying model incorporating comorbidities, age, cytogenetic, and molecular risks, allows patients to be divided into four groups based on mortality risk. Our patient, with a score of 8, belonged to the 3rd group, namely moderate-high risk of mortality. Consequently, our purpose was to deliver a therapy as effective as possible with the lowest amount of toxicity.

Currently, in the landscape of new target drugs, the addition of VEN to hypomethylating agents (HMAs) has proven to be effective in both newly diagnosed and relapsed/ refractory AML,[14,15] with a good safety profile.[16] Then, it is increasingly recognized as the preferred treatment option for patients deemed unfit for IC. Moreover, VEN has demonstrated efficacy in addressing extramedullary involvement of AML[17,18] and in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia with skin infiltrates.[19] However, in the context of this specific AML extramedullary disease localization, the impact of demethylating agents associated with VEN remains largely unknown.

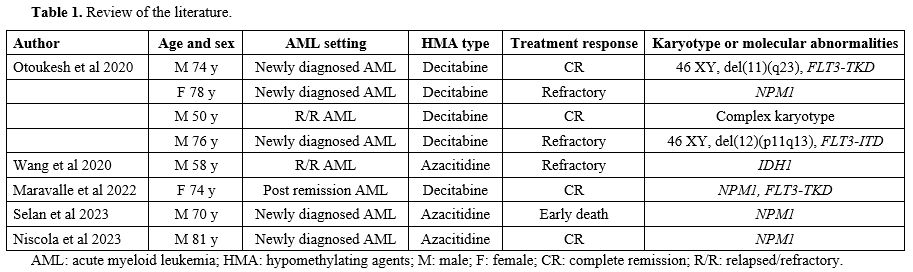

Pubmed research using a Boolean combination of the words "leukemia cutis", "cutaneous extramedullary leukemia", "cutaneous myeloid sarcoma", and "venetoclax” showed only eight previous reports of LC treated with HMAs associated with VEN (HMAs-VEN) (Table 1).[18,20-23] In 62% of them, skin involvement was concomitant to AML diagnosis; instead, 25% of the cases were relapsed/refractory AML. NPM1 was the most frequent molecular alteration in this setting (50%). The preferred hypomethylated agent was decitabine, used in 62% of the cases. In half of the reported patients and in our experience, the association was effective and led to a complete response. In our case, AZA-VEN was well-tolerated, with an improvement in the patient's quality of life.

Therefore, HMAs-VEN appears to be a viable combination for AML with skin involvement in patients ineligible for IC. However, randomized studies are needed to establish the appropriate dosage and duration schedule. The question remains as to whether the association will be capable of maintaining a sustained remission in both BM and skin.

Finally, extramedullary disease is known to be associated with CNS spreading,[6,24,25] and intensive chemotherapy protocols are able to sterilize CSF to improve prognosis and prevent CNS seeding. However, in the context of non-intensive treatment, the ability to overcome the blood-brain barrier is still a matter of debate. Thus, even if reports suggest that VEN might reach a therapeutic concentration in CSF,[26,27] we decided to apply CNS prophylaxis with medicated lumbar punctures.

Conclusions

Skin has always been considered a sanctuary for leukemic cells, therefore the optimal management of AML with LC is not established yet. Our case showed the positive effect of HMAs-VEN on LC despite the short follow-up. This association has proven to be a promising treatment for patients unable to undergo IC, even though accumulating experience and further studies are needed to establish HMAs-VEN as a reliable treatment option in this category of patients.Data availability

All relevant data are included in this article. For additional data inquiries, an additional request can be directed to the corresponding author.References

- Parsi M, Go MS, Ahmed A (2024) Leukemia Cutis. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL)

- Shaikh

BS, Frantz E, Lookingbill DP (1987). Histologically proven leukemia

cutis carries a poor prognosis in acute nonlymphocytic leukemia. Cutis

39(1):57-60. PMID: 3802911.

- Wang

CX, Pusic I, Anadkat MJ (2019). Association of Leukemia Cutis With

Survival in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. JAMA Dermatol 155:826. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.0052 PMid:30969325 PMCid:PMC6583862

- Agis

H, Weltermann A, Fonatsch C, et al. (2002). A comparative study on

demographic, hematological, and cytogenetic findings and prognosis in

acute myeloid leukemia with and without leukemia cutis. Ann Hematol

81:90-95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-001-0412-9 PMid:11907789

- Kaddu

S, Zenahlik P, Beham-Schmid C, et al. (1999). Specific cutaneous

infiltrates in patients with myelogenous leukemia: a clinicopathologic

study of 26 patients with assessment of diagnostic criteria. J Am Acad

Dermatol 40:966-978. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0190-9622(99)70086-1 PMid:10365929

- Fianchi

L., Quattrone M., Criscuolo M., Bellesi S., Dragonetti G., Maraglino

A.M.E., Bonanni M., Chiusolo P.1, Sica S., Pagano L. Extramedullary

involvement in acute myeloid leukemia. A single center ten years'

experience.Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2021, 13(1):

e202103099)70086-1 https://doi.org/10.4084/MJHID.2021.030 PMid:34007418 PMCid:PMC8114885

- Wagner

G, Fenchel K, Back W, et al. (2012). Leukemia cutis - epidemiology,

clinical presentation, and differential diagnoses. J Deutsche Derma

Gesell 10:27-36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1610-0387.2011.07842.x PMid:22115500

- Sorror

ML, Storer BE, Fathi AT, et al. (2017). Development and Validation of a

Novel Acute Myeloid Leukemia-Composite Model to Estimate Risks of

Mortality. JAMA Oncol 3:1675. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.2714 PMid:28880971 PMCid:PMC5824273

- Bakst RL, Tallman MS, Douer D, Yahalom J (2011). How I treat extramedullary acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 118:3785-3793. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2011-04-347229 PMid:21795742

- Heudobler

D, Klobuch S, Thomas S, et al. (2018). Cutaneous Leukemic Infiltrates

Successfully Treated With Biomodulatory Therapy in a Rare Case of

Therapy-Related High Risk MDS/AML. Front Pharmacol 9:1279. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2018.01279 PMid:30483125 PMCid:PMC6243099

- Rubin CM, Arthur DC, Meyers G, et al. (1985). Leukemia cutis treated with total skin irradiation. Cancer 55:2649-2652. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19850601)55:11<2649::AID-CNCR2820551120>3.0.CO;2-X PMid:3888368

- Hsieh

C-H, Tien H-J, Yu Y-B, et al. (2019) Simultaneous integrated boost with

helical arc radiotherapy of total skin (HEARTS) to treat cutaneous

manifestations of advanced, therapy-refractory cutaneous lymphoma and

leukemia - dosimetry comparison of different regimens and clinical

application. Radiat Oncol 14:17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-019-1220-5 PMid:30691490 PMCid:PMC6348688

- Robak

E, Braun M, Robak T (2023). Leukemia Cutis-The Current View on

Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Cancers (Basel) 15:5393. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15225393 PMid:38001655 PMCid:PMC10670312

- DiNardo,

C. D., Jonas, B. A., Pullarkat, V., Thirman, M. J., Garcia, J. S., Wei,

A. H., Konopleva, M., Döhner, H., Letai, A., Fenaux, P., Koller, E.,

Havelange, V., Leber, B., Esteve, J., Wang, J., Pejsa, V., Hájek, R.,

Porkka, K., Illés, Á., Lavie, D., Pratz, K. W. (2020). Azacitidine

and Venetoclax in Previously Untreated Acute Myeloid Leukemia. The New

England journal of medicine, 383(7), 617-629. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2012971 PMid:32786187

- Zorzetto,

F., Scalas, A., Longu, F., Isoni, M. A., Angelucci, E., & Fozza, C.

(2024). Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis Secondary to Refractory

Acute Myeloid Leukemia Resolved after Second-Line Treatment with

Azacitidine plus Venetoclax. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis, 16(1),

e2024011. https://doi.org/10.4084/MJHID.2024.011 PMid:38223479 PMCid:PMC10786137

- Cristiano,

A., Palmieri, R., Fabiani, E., Ottone, T., Divona, M., Savi, A.,

Buccisano, F., Maurillo, L., Tarella, C., Arcese, W., & Voso, M. T.

(2022). The Venetoclax/Azacitidine Combination Targets the Disease

Clone in Acute Myeloid Leukemia, Being Effective and Safe in a Patient

with COVID-19. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis, 14(1), e2022041. https://doi.org/10.4084/MJHID.2022.041 PMid:35615323 PMCid:PMC9083951

- Lachowiez

C, DiNardo CD, Konopleva M (2020). Venetoclax in acute myeloid leukemia

- current and future directions. Leukemia & Lymphoma

61:1313-1322. https://doi.org/10.1080/10428194.2020.1719098 PMid:32031033

- Otoukesh

S, Zhang J, Nakamura R, et al. (2020). The efficacy of venetoclax and

hypomethylating agents in acute myeloid leukemia with extramedullary

involvement. Leukemia & Lymphoma 61:2020-2023. https://doi.org/10.1080/10428194.2020.1742908 PMid:32191144

- Dimou

M, Iliakis T, Paradalis V, et al. (2021). Complete eradication of

chronic lymphocytic leukemia with unusual skin involvement of high

mitotic index after time-limited venetoclax/obinutuzumab treatment.

Clin Case Rep 9:e04514. https://doi.org/10.1002/ccr3.4514 PMid:34322260 PMCid:PMC8299089

- Maravalle

D, Filosa A, Bigazzi C, et al. (2022). Long‐term remission of

extramedullary cutaneous relapse of acute myeloid leukemia (leukemia

cutis) treated with decitabine‐venetoclax. eJHaem 3:517-520. https://doi.org/10.1002/jha2.388 PMid:35846058 PMCid:PMC9175852

- Selan

M, Stopajnik N (2023). Acute onset of leukemia cutis in a

70-year-old-patient: a case report. Acta Dermatovenerologica Alpina

Pannonica et Adriatica 32. https://doi.org/10.15570/actaapa.2023.33

- Wang

J, Ye X, Fan C, et al. (2020). Leukemia cutis with IDH1, DNMT3A and

NRAS mutations conferring resistance to venetoclax plus 5-azacytidine

in refractory AML. Biomark Res 8:65. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40364-020-00246-9 PMid:33292606 PMCid:PMC7687845

- Niscola

P, Mazzone C, Fratoni S, et al. (2023). Acute Myeloid Leukemia with

NPM1 Mutation and Disseminated Leukemia Cutis: Achievement of Molecular

Complete Remission by Venetoclax/Azacitidine Combination in a Very Old

Patient. Acta Haematol 146:408-412. https://doi.org/10.1159/000531101 PMid:37231772

- Yaşar

HA, Çinar OE, Yazdali Köylü N, et al. (2021). Central nervous system

involvement in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Turk J Med Sci

51:2351-2356. https://doi.org/10.3906/sag-2103-127 PMid:33932973 PMCid:PMC8742469

- Bar

M, Tong W, Othus M, et al. (2015). Central Nervous System Involvement

in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Patients Undergoing Hematopoietic Cell

Transplantation. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation

21:546-551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.11.683 PMid:25545726 PMCid:PMC4720268

- Condorelli

A, Matteo C, Leotta S, et al (2022). Venetoclax penetrates in

cerebrospinal fluid of an acute myeloid leukemia patient with

leptomeningeal involvement. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 89:267-270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-021-04356-5 PMid:34590164

- Reda G, Cassin R, Dovrtelova G, et al (2019). Venetoclax penetrates in cerebrospinal fluid and may be effective in chronic lymphocytic leukemia with central nervous system involvement. Haematologica 104:e222-e223. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2018.213157 PMid:30765472 PMCid:PMC6518888