Introduction

WM has no cure, but therapies can improve survival. Adverse effects of all WM therapies may vary depending on the drug class and the individual patient. No data shows that treating asymptomatic WM improves mortality while delaying therapy until symptoms do not affect the disease progression or patient outcomes. The treatment plan involves selecting drugs, determining the order of interventions, and deciding when to start, stop, or pause therapy. When we plan treatment, we might consider each therapy's advantages and disadvantages, evaluate the treatment duration (fixed duration or continuous), the treatment goal (achieving long-term remission or managing the disease), and the potential impact of side effects on other health conditions. This careful selection ensures that therapies align with the patient's health goals and medical history.Indication for initial treatment

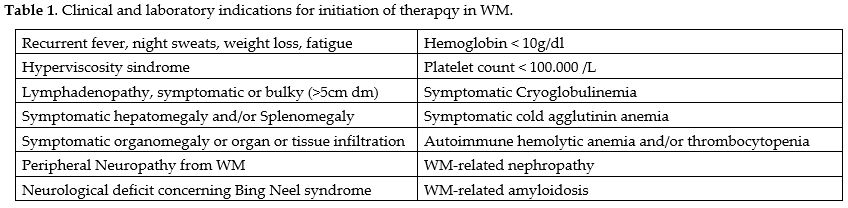

Treatment for WM/LPL patients should only be initiated when they exhibit symptoms, as per the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines and the second International Workshop on Waldenstrom Macroglobulinemia.[1-2] Asymptomatic patients can be monitored without immediate therapy over an extended period to reduce treatment-related risks.[3] Approximately 1.5% of IgM MGUS and 12% of smoldering WM patients develop WM each year.[4-6] Symptomatic progression takes approximately 9.2 years for low-risk, 4.8 years for moderate-risk, and 1.8 years for high-risk disease progression.[7] Low-risk patients could be monitored annually, intermediate-risk patients every six months, and high-risk patients every three months. Importantly, IgM level should not determine WM treatment. While asymptomatic patients with IgM levels > 6000 mg/dl should receive treatment, it's important to note that serum IgM levels may not always correlate with clinical symptoms. Always exonerate other conditions that may contribute to the development of symptoms. Constitutional symptoms like fever, night sweats, anemia, fatigue, or weight loss necessitate therapy when linked to the disease.[8-12] A worsening lymphadenopathy or splenomegaly following treatment is another indication to initiate treatment. Treatment is also required for Marrow Infiltration Anemia, characterized by hemoglobin levels below 100 g/L or platelets below 100 109/L. Hyperviscosity syndrome, sensory peripheral neuropathy, systemic amyloidosis, renal insufficiency, and symptomatic cryoglobulinemia may require treatment[8-12] (Table 1).First-line therapy

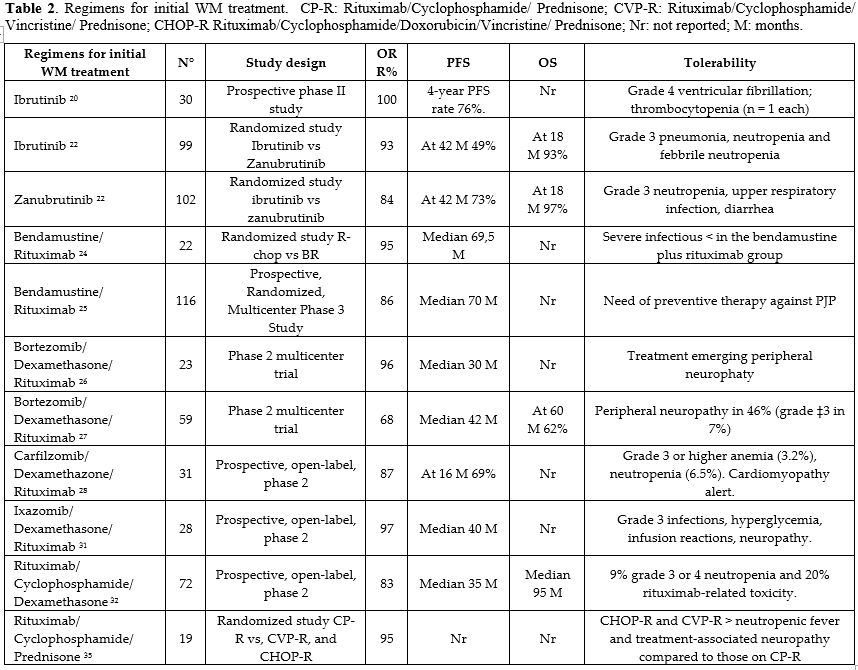

Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia (WM) is rare; few randomized studies have compared first-line treatment approaches. Phase II or retrospective studies have provided most WM treatment evidence. Due to the many treatment options and the absence of randomized trials, current guidelines suggest various initial treatments for personalized therapy (Table 2).Selection of BTK Inhibitor Therapies Based on Genetic Profile

Patients with WM can be classified into three groups based on their MYD88 and CXCR4 mutational status: those who have MYD88 mutations but no CXCR4 mutations (MYD88MUT/CXCR4WT); those who have both MYD88 and CXCR4 mutations (MYD88MUT/CXCR4MUT); and those who do not have both MYD88 and CXCR4 mutations (MYD88WT/CXCR4WT). Among all the genomic groups, the MYD88WT/CXCR4WT group exhibited the lowest response rate and the shortest progression-free survival (PFS) when treated with ibrutinib monotherapy. This group also showed lower rates of very good partial response (VGPR) and longer to achieve a major response to ibrutinib monotherapy. Patients with MYD88MUT/CXCR4MUT status who require a rapid response benefit from chemotherapy regimens; nevertheless, those who do not require an immediate response should use BTK inhibitors.[13-15] BTK inhibitors such as ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, and zanubrutinib can benefit patients with WM but can cause adverse effects like atrial fibrillation, bleeding, cytopenias, hypertension, gastrointestinal symptoms, infections, and arthralgias. Atrial fibrillation is common in 5% to 15% of patients with WM exposed to BTK inhibitors, according to recent studies. Patients often experience increased bleeding and bruising, highlighting the importance of judiciously using concomitant anticoagulants or antiplatelet agents.[16] Symptoms may require a transient medication hold, and rheumatologic symptoms may need a dose reduction or referral to a rheumatologist. Approximately 20% of patients with WM who temporarily hold BTK inhibitors experience withdrawal symptoms.[17] A retrospective study on 353 patients receiving ibrutinib revealed that 27% had to reduce their dosage due to side effects such as rheumatologic, cardiac, nail/hair/skin changes, cytopenias, gastrointestinal, and bleeding/bruising issues. Dose reductions were more common in patients over 65 years and females. If supportive care and dose reduction do not provide sufficient symptom relief, patients could consider transitioning to another BTK inhibitor, particularly zanubrutinib.[18]Ibrutinib with or without Rituximab

The results of a phase II study using ibrutinib to treat 30 people with previously untreated WM showed an ORR of 100%, a very good partial response (VGPR) rate of 30%, and a progression-free survival (PFS) rate of 76% at 48 months.[19] A phase III trial (iNNOVATE study) randomly assigned treatment-naive and previously treated patients to receive either Rituximab or Rituximab and ibrutinib. At 30 months, the PFS rate for ibrutinib and Rituximab was 82%, compared to 28% for Rituximab. This advantage was evident regardless of mutational status. The respective response rates were 72% and 32%. 12 percent of ibrutinib-treated patients had atrial fibrillation. 13% of patients experienced hypertension. Only 8% of patients in the ibrutinib arm and 47% in the rituximab arm experienced a flare. When lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma affects the central nervous system, ibrutinib should be the first therapeutic option considered.[20-21]Zanubrutinib

Compared to ibrutinib, zanubrutinib is a BTK inhibitor with a greater affinity for BTK. Patients with WM who had not been treated before, who had relapsed, or were not responding to treatment were randomly assigned to either ibrutinib or zanubrutinib in the phase III ASPEN study. Of the patients, 26% had a CXCR4 mutation, and all had a mutation in MYD88 (L265P). There was no statistically significant difference in VGPR (28% vs 19%; P5.09) between the zanubrutinib and ibrutinib groups. For zanubrutinib, the 42-month PFS rate was 78%, and for ibrutinib, it was 70%. In patients with CXCR4 mutations, Zanubrutinib had higher PFS (73% vs. 49%) and VGPR (21% vs. 10%) rates at 42 months than ibrutinib. Aspen safety data showed that zanubrutinib monotherapy was safer than ibrutinib. There was less atrial fibrillation (4% vs. 17%) and fewer nonhematologic side events. Except for neutropenia, which was twice as likely to occur with zanubrutinib as with ibrutinib (29% vs. 13%), the rate of hemorrhagic adverse events was mostly unchanged.[22-23]Bendamustine/Rituximab (BR)

In a large, randomized, multicenter phase III trial of people with indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma who had not received prior treatment, the Study Group Indolent Lymphomas (StiL) examined the effectiveness of bendamustine plus Rituximab (BR) and Rituximab plus CHOP. This study involved 40 out of 41 individuals with WM/LPL who were available to evaluate treatment response. BR therapy resulted in a significantly longer PFS of 69.5 months compared to 28.5 months with CHOP-R after 45 months of follow-up.[24] In the StiL NHL-2008 MAINTAIN trial, individuals treated with bendamustine and Rituximab achieved a median PFS of 65.3 months. Patients receiving bendamustine/Rituximab should consider taking preventive measures against Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PJP).[25]Bortezomib/Dexamethasone/Rituximab (BDR)

The Waldenström Macroglobulinemia Clinical Trials Group (WMCTG) found that BDR had an overall response rate (ORR) of 96% in people who had just been diagnosed with WM. Of these patients, 83% had a partial response (PR). Eighty percent of patients had no disease progression after a median follow-up of two years, including every patient with VGPR or better. Peripheral neuropathy is the primary side effect of bortezomib-based regimens.[26-27] This study observed peripheral neuropathy in grade 3 in 30 percent of patients receiving bortezomib treatment twice weekly. Bortezomib can be administered subcutaneously once weekly to reduce the likelihood of developing peripheral neuropathy. Patients unable to tolerate Rituximab may be candidates for an alternative treatment regimen comprising subcutaneous bortezomib combined with dexamethasone.[26-27]Carfilzomib/Rituximab/Dexamethasone

A prospective phase II study looked at carfilzomib, Rituximab, and dexamethasone in 31 newly diagnosed WM/LPL patients who were showing symptoms. The ORR was 87%, with 64 patients followed for an extended period, and the median PFS was 46 months. The study found that the MYD88 (L265P) mutation status did not impact the response to this regimen. This study did not observe any significant peripheral neuropathy. Several patients experienced IgA and IgG depletion, necessitating the truncation of therapy and/or intravenous immunoglobulins. Of note, this regimen could cause cardiac and pulmonary toxicity, especially in older patients.Ixazomib/Rituximab/Dexamethasone

A prospective phase II study evaluated the combination of ixazomib, Rituximab, and dexamethasone in 26 patients with symptomatic WM. All enrolled patients carried the MYD88 (L265P) mutation, with 58% also carrying a CXCR4 mutation. The median time to respond was 8 weeks. Overall, major and VGPR rates were 96%, 77%, and 19%, respectively, and the median time to respond was 8 weeks. The median PFS was 40 months, the median duration of response was 38 months, and the median time to the next treatment was 40 months. The CXCR4 mutational profile did not affect PFS, the duration of the response, or the time to the next treatment.[30-31]Rituximab, Cyclophosphamide, and Dexamethasone (DRC)

The results of DRC treatment in 50 WM naïve patients showed an ORR of 96% and a median PFS of 34 months. The response rate and duration were unaffected by MYD88 mutational status. Another prospective study with 72 people who had untreated WM found that treatment with DRC had an ORR of 83%, with 7% having a complete response (CR) and 67% having a PR. The 2-year PFS rate for all evaluable participants was 67%, whereas it was 80% for responders. Patients tolerated the DRC regimen well, with 9% reporting grade 3 or 4 neutropenia and approximately 20% experiencing rituximab-related toxicity. Based on the IPSSWM risk classification, the OS rates after 8 years were 100% for low-risk patients, 55% for intermediate-risk patients, and 27% for high-risk patients (P =.005).[32-34]Rituximab, Cyclophosphamide, and Prednisone (CP-R)

Studies have demonstrated the effectiveness and reduced side effects of cyclophosphamide/prednisone/Rituximab (CP-R) compared to more aggressive cyclophosphamide-based protocols. In particular, a study examined the outcomes of WM patients treated with CHOP-R (n = 23), CVP-R (n = 16), or CP-R (n = 19). Serum IgM levels were significantly higher in patients receiving CHOP-R (P = 0.015), whereas baseline parameters were comparable across the three cohorts. The ORR and CR for the three regimens were 96% for CHOP R, 88% for CVP-R, and 12% for CP-R, respectively. Patients receiving CHOP-R and CVP-R experienced a greater incidence of neutropenic fever and treatment-associated neuropathy compared to those on CP-R.[35]Rituximab monotherapy

Although single-agent Rituximab with either a conventional or prolonged dose has response rates ranging from 25% to 45%, it helps treat patients with WM.[36] After the initial administration of rituximab therapy, we observed a transient increase in IgM levels in 40% to 50% of patients, commonly called IgM flare. Rituximab-induced IgM flares can exacerbate hyperviscosity symptoms, as well as worsen cryoglobulinemia, neuropathy, and other IgM-related issues. While plasmapheresis might be required to lower IgM levels, these levels could last for months and do not signify a treatment failure. To reduce the chance of an IgM flare-up with symptoms, patients with high IgM levels (typically 4,000 mg/dL or greater) may wish to have prophylactic plasmapheresis before starting rituximab.[37-39]Assessment of response and follow-up after the first line of therapy

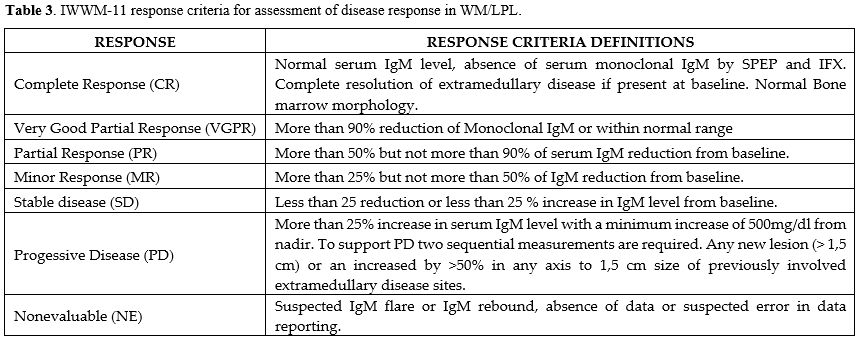

The objective of treatment is to alleviate symptoms and mitigate the risk of organ impairment. We recommend assessing the treatment response using consensus panel criteria after the primary therapy[40] (Table 3). We advise establishing the timing of response evaluations, including BM biopsy, on a case-by-case basis, informed by clinical and laboratory assessments, as there is no agreement on this matter. The use of IgM as a surrogate for disease markers poses a significant problem, as these markers can fluctuate even while specific treatments are eradicating cancer cells. For example, Rituximab may elevate serum IgM levels, whereas bortezomib and ibrutinib can decrease IgM levels in certain patients, although they do not induce cancer cell death. It is critical to recognize that certain clinical responders may delay the post-therapy decline or nadir in IgM levels for several months. It is essential not to think of consistently high IgM levels as a sign of medication resistance without looking at other signs of therapeutic response, like a rise in hemoglobin levels, bone marrow clearance, and/or the disappearance of symptoms.Treatment of relapsed and refractory Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia

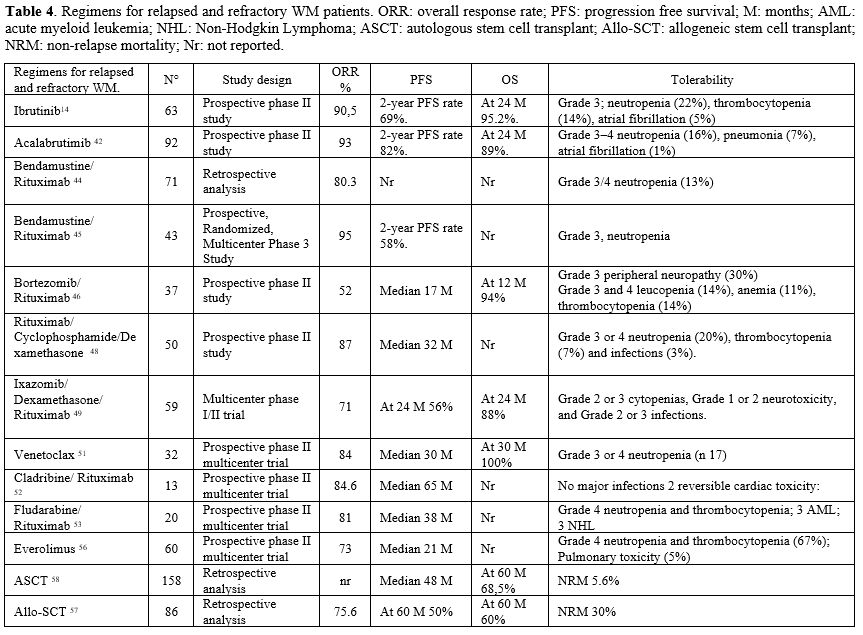

Numerous choices exist for individuals experiencing recurrence following first-line therapy or those who are refractory. Biological age, comorbidities, fitness, and accessibility are critical considerations in treatment selection. People who already have or are developing diseases like peripheral neuropathy, BNS, cryoglobulinemia, AL amyloidosis, hyperviscosity syndrome (HVS), and acquired clotting factor deficits need to find and change their treatment plans. The characteristics of recurrence (fast, gradual, or high-grade transformation) will affect the treatment selection, as will the degree of hematopoietic reserve. The optimal treatment for relapsed or refractory (RR) WM is based upon the initial method, typically involving chemoimmunotherapy (CIT) and/or a covalent BTK inhibitor (cBTKi). If the duration of response (DoR) exceeds three years after CIT, exploring additional CIT using non-cross-reactive chemicals may be necessary. If previous treatment included only cBTKi, then CIT might be a plausible option upon relapse. If a patient experiences relapsed/refractory WM following CIT and cBTKi, they may choose non-covalent Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors (such as pirtobrutinib), novel anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies, BCL-2 inhibitors (such as venetoclax), or more intensive chemotherapy regimens. Patients who are younger and healthier and have not responded to both CIT and cBTKi may be good candidates for an autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT), especially when not many clinical trials or other new therapies are available. Patients eligible for ASCT must possess a chemo-sensitive disease (Table 4).Ibrutinib single agent or in combination with Rituximab

In 2015, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Ibrutinib for the treatment of relapsed Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM), following a significant phase II study. The ORR was 90.5%, while the major response rate was 73%. The wild type MYD88 exhibited a response rate of 71.4%, with major responses constituting only 28.6% of this total. Adverse effects comprised atrial fibrillation, diarrhea, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia.[14] The long-term follow-up of this cohort demonstrated ORR and major response rates of 91% and 79%, respectively, at a median follow-up of 59 months. Patients exhibiting mutated MYD88 alongside wildtype CXCR4 demonstrated elevated response rates and reduced times to response. The presence of a CXCR4 mutation was associated with a reduced response rate.[15]In the iNNOVATE trial, 150 WM patients received either ibrutinib-rituximab or placebo-rituximab. Approximately 55% of these patients had undergone prior treatment. Major response rates were higher in the ibrutinib-rituximab group (72% vs. 32%). In the ibrutinib-rituximab group, more people had side effects of grade 3 or higher. These side effects included atrial fibrillation (12%) and high blood pressure (13% vs. 4%). Major bleeding was equal in both groups (4%). At 30 months, the PFS was 82% in the ibrutinib-rituximab arm and 28% in the placebo-rituximab arm.[21]

In people with WM who had not previously received treatment or who had relapsed or failed treatment, the randomized, open-label Phase 3 ASPEN trial directly compared zanubrutinib to ibrutinib. The zanubrutinib results were better. More importantly, patients responded strongly to zanubrutinib therapy regardless of CXCR4 mutation status. Additionally, zanubrutinib had fewer grade 3 or higher toxicities and was generally better tolerated.[41]

Acalabrutinib

A multicenter phase II trial was performed to look at untreated and previously treated macroglobulinemia. Acalabrutinib was administered until toxicity or disease progressed. One hundred six patients received treatment. The response rate for both untreated and relapsed individuals was 93%. Sixteen percent of individuals experienced neutropenia, seven percent suffered pneumonia, and merely one percent exhibited grade 3 atrial fibrillation. The treatment provides a superior safety profile compared to ibrutinib. Adverse events leading to therapy cessation occurred in 7% of patients. No statistically significant differences were observed in response time or progression-free survival between treatment-naive individuals and those who had received treatment. Patients with mutant MYD88 and those with wildtype MYD88 had overall response rates of 94% and 79%, respectively.[42]Bendamustine/Rituximab

A phase II study of relapsed/refractory WM patients treated with bendamustine-based treatment indicated an overall response rate of 83.3%, exhibiting a median progression-free survival of 13.2 months.[42] Individuals with relapsed or refractory Waldenström macroglobulinemia were examined in phase I and phase II trials to evaluate the efficacy of bendamustine in conjunction with Rituximab. Patients have previously had a median of 2 lines of therapy (range, 1-5). The ORR recorded an 80.2% rate. A separate study assessed the effectiveness of BR and R-CD. Out of 160 patients, 60 received BR (43 with relapsed/refractory WM), and 100 received R-CD (50 with relapsed/refractory WM). The ORR was 95% for BR compared to 87% for R-CD (P = 0.45), and the median PFS was 58 months for BR versus 32 months for R-CD (2-year PFS: 66% versus 53%; P = 0.08).[43-45]Bortezomib/Dexamethasone/Rituximab

When bortezomib is used to treat relapsed disease, it has an ORR of 60% when given alone and 70% to 80% when combined with Rituximab with or without dexamethasone. In contrast to alkylating agents, the responses happened very quickly, on average, within 1.4 months. When administered as a single agent, the ORR was 60%, and when combined with Rituximab with or without dexamethasone, it ranged from 70% to 80%.[46] For patients with only a ten-year life expectancy, peripheral neuropathy poses a serious drawback. Grade 3 peripheral neuropathy may occur in 30% of patients using the twice-a-week dosing schedule of bortezomib and in 10% of patients receiving once-a-week dosing. Weekly bortezomib administration reduced neurotoxicity without affecting response rates significantly.[47]Rituximab, Cyclophosphamide, and Dexamethasone

In a phase II investigation, one hundred patients with Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM) were studied, comprising 50 individuals who had at least one cycle of treatment for relapsed/refractory WM and 50 individuals who got at least one cycle of the same regimen for newly diagnosed WM. In the relapsed/refractory context, the median PFS reported was 32 months (95% confidence interval: 15–51), with PFS rates at 2 and 4 years being 54% and 34%, respectively.[48]Ixazomib/rituximab/dexamethasone

A phase I-II study found an overall response rate (ORR) of 71% in 59 patients treated with ixazomib/rituximab/dexamethasone who had received a median of two previous therapies. Of these patients, 14% experienced a very good response, 37% experienced a partial response, and 20% experienced a minor response. The response length was observed within a range of 36 months, with the median duration being 36 months. Following the patients for a median of twenty-four months revealed PFS and OS rates of 56 percent and 88 percent, respectively.[49]Venetoclax

A phase II trial looked at venetoclax as a single treatment for 33 people who had already been treated for WM. All patients had a MYD88 (L265P) mutation, and 17 (53%) exhibited a CXCR4 mutation. At a median follow-up of 33 months, the median PFS was 30 months. At the data cutoff, the overall survival at 30 months was 100%, and the objective response rate was 84%. The predominant grade 3-4 adverse event was neutropenia, occurring in 42% of cases. Venetoclax is both safe and extremely effective for people with previously treated WM, including those who have already received BTK inhibitors. The mutation status of CXCR4 did not influence the treatment response. The appropriate duration of venetoclax therapy in WM remains undetermined.[50,51]Analogues of nucleosides

A phase II trial The combination of cladribine and Rituximab was evaluated in 29 patients with newly diagnosed or previously treated WM, yielding reported ORR and CR of 90% and 24%, respectively.[52] A multicenter, prospective trial evaluated the efficacy of fludarabine and Rituximab in patients with WM (n=43) who had undergone fewer than two prior therapies, with 63% having received no previous treatment. The OR rate was 95%. All patients reported a median time to progression of 51.2 months, with untreated patients showing a longer duration (P = 0.017) and those achieving at least a VGPR exhibiting an extended progression time (P = 0.049). Following a median follow-up period of 40.3 months, three cases of transformation to aggressive lymphoma and three cases of myelodysplastic syndromes/acute myeloid leukemia have been reported.[53] Additionally, The FCR regimen was utilized in a multicenter prospective trial involving patients with WM who had not received prior treatment or had been pretreated with chemotherapy. In this study, 65% of participants received FCR as first-line treatment, 28% had relapsed disease, and 7% had a disease that was refractory to prior treatment. The findings indicated that FCR elicits rapid responses, achieving rates of 79%, along with elevated rates of CR and VGPR.[54,55] The administration of FCR treatment carries a risk of PJP, including the potential for late onset of the infection.Everolimus

Everolimus, a mTOR inhibitor, offers patients with relapsed or refractory WM an alternate therapy option that utilizes a unique mechanism of action. A phase I study utilized everolimus in patients with relapsed/refractory Waldenström macroglobulinemia.[56] Sixty individuals underwent treatment. The ORR was 73%, comprising a 50% partial response and a 23% minimal response (MR). The median PFS duration was 21 months. Sixty-seven percent of participants indicated grade 3 or 4 toxicity. Sixty-two percent of patients reduced their dosage due to toxicity. The most commonly reported hematologic harm was cytopenia. Five percent of participants demonstrated pulmonary toxicity.Transplantation in WM

A limited number of case series have reported outcomes of ASCT in the setting of relapse. ASCT was ineffective for WM patients who were chemoresistant or had undergone more than three lines of treatment. The European Bone Marrow Transplant Registry (EBMT) reported that among 158 WM patients, the OS and PFS rates at 5 years were 68.5% and 39.7%, respectively. After 5 years, an updated EBMT trial found that 46% of people with WM who had autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) did not get worse, and 65% did have OS. Only a select group of patients might receive Allo-SCT due to its significant non-relapse mortality (NRM).[57-58] A limited retrospective study of extensively pretreated WM patients indicated that allo SCT exhibited a graft versus WM effect, potentially enhancing progression-free survival (PFS) and OS in individuals who endured toxicity. EBMT (n = 86) and the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR, n = 144) have documented the most extensive series of WM patients undergoing allogeneic SCT. Although the median PFS approached 5 years in both cohorts, the non-relapse mortality (NRM) was notably significant at approximately 30%, with a marginally lower rate observed in transplants subjected to reduced intensity conditioning.[57-58](CAR) T cell therapy

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy has become an established treatment option for various B cell leukemias and lymphomas. Considering these positive outcomes and the typically high CD19 positivity in WM clones, CAR-T cell therapy presents a logical choice for patients with WM who have tried all other treatment alternatives. A recent study demonstrated that second-generation anti-CD19 CAR T cells exhibit anti-WM activity in both in vitro and in vivo settings.[59] The initial series of three patients administered CAR T products exhibited indications of safety and clinical efficacy. The treatment was well tolerated clinically, exhibiting only grade 1–2 toxicities. The responses of all three patients varied, ranging from stable disease with a hematologic response to a prolonged, complete response. All patients, however, experienced subsequent disease progression.[59]Histological Transformation

Studies show that 2.4% to 11% of patients with WM undergo histological transformation, predominantly to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).[60] Ninety-one percent of the 77 people in the largest reported series with secondary DLBCL and WM had involvement of extranodal sites such as the central nervous system (CNS), skin, and testicles. The de novo DLBCL variant is significantly associated with the MYD88 mutation across all examined locations. The median duration between diagnosis and high-grade transformation in this series was 4.6 years, with 21 percent of patients (16 individuals) having never received treatment for WM. A tissue biopsy is required for the diagnosis of histological transformation. PET-CT scanning can assist in directing the biopsy site. The prognosis for patients undergoing this transformation is typically worse than that of individuals with de novo DLBCL, underscoring the significance of early detection and intervention. Frequent monitoring and timely treatment adjustments significantly influence patient outcomes in these cases. The treatments and routines used for de novo DLBCL, especially R-CHOP in the right patients, also work for high-grade transformation to DLBCL.[61-62]Secondary Malignancies

WM may increase the risk of secondary cancers. SEER data on 4,676 WM patients was used to estimate secondary malignancies. Following WM diagnosis, researchers found 681 tumor cases (15%), comprising 484 solid and 174 hematologic. With an overall SIR of 1.49 and a median duration for secondary malignancies of 3.7 years, the cumulative incidence was 10% at five years and 16% at ten years. More WM patients had thyroid (SIR 2.7), melanoma (SIR 1.9), and lung cancer (SIR 1.5) than the overall population. WM patients had a higher incidence of aggressive lymphomas (SIR 4.6) and acute leukemia (SIR 3.2).[63-64] Younger WM patients showed a higher incidence of secondary malignancies than older ones. Secondary cancers were equally common across gender and race. The risk of solid and hematologic cancers increased five years following WM diagnosis, based on latency. In another population-based analysis of 6,865 SEER-18 WM patients, we examined secondary malignancies in WM patients. 346 In this research, WM patients with colorectal cancer (HR 2), melanoma (HR 2.6), and aggressive lymphoma (HR 1.4) had lower overall survival than the general population.[63-64]Bing-Neel syndrome (BNS)

In Bing-Neel syndrome (BNS), lymphoplasmacytic cells migrate to the central nervous system (CNS). Brain and spine MRI with gadolinium and cerebrospinal fluid tests (flow cytometry and PCR for MYD88 L265P) can help secure the diagnosis of BNS. Systemic therapy options include BTK inhibitors, chemotherapy agents, intrathecal methotrexate, and radiotherapy. BNS is a rare and usually late manifestation in individuals with WM, and its development is generally associated with a worse prognosis. WM patients who develop BNS early in the disease course might have a better outcome. The intricate relationship between systemic disease and B-cell manifestations necessitates careful management and observation. Early detection and appropriate therapeutic interventions can significantly impact outcomes in this challenging clinical context.[65-67]Supportive care

HSV and HZV prophylaxis may benefit patients needing extensive, immunosuppressive, or bortezomib-based treatment. Hematologic malignancies more frequently reactivate HBV, so screening for HBV is necessary before starting therapy with carfilzomib, Rituximab, or ofatumumab. Testing for Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) or core antigen antibodies can be used for screening. We recommend entecavir prophylaxis for patients who have fully cured HBV and an HBcAb antibody. We recommend screening and antiviral treatment for patients with high hepatitis B surface antibody levels. We highly recommend PJP for immunosuppressive and demanding treatments. SARS-CoV-2 and seasonal flu vaccines should be available to all WM patients. Chickenpox vaccinees can now get Shingrix®, a live virus-free vaccination. Local antibiotic treatments should assess hypogammaglobulinemia and recurring bacterial infections. Patients with secondary hypogammaglobulinemia and recurrent infection despite antimicrobial prophylaxis might require immunoglobulin replacement therapy.Outlook

The multitude of medications currently available and under development highlights the constantly evolving management of WM as ongoing trials accumulate data from different strategies.Here are some important frontline studies: the randomized phase 2 trial viWA-1 (NCT05099471) compared venetoclax-rituximab and DRC (6 cycles); the phase 2 multicenter study of zanubrutinib, bendamustine, and Rituximab (ZEBRA Trial) (NCT06561347); the phase 2 study of sonrotoclax (BGB-11417-203) alone and with zanubrutinib (NCT05952037).

For relapsed patients are worthy of mention: The prospective phase II Study (NCT05734495) evaluating the novel non-covalent BTK inhibitor pirtobrutinib in combination with the BCL2 antagonist venetoclax; the prospective phase II clinical trial designed to evaluate the use of loncastuximab tesirine, a CD19 antibody drug-conjugate (NCT05190705); the prospective phase 2, single-arm, open-label trial of epcoritamab a bispecific antibody (NCT06510491); The phase 2 [NCT02952508) Iopofosine I 131 a novel radiopharmaceutical composed of a lipid raft-targeting phospholipid ether covalently bound to 131I; the phase 1 study evaluating a novel Bruton Tyrosine Kinase Degrader BGB-16673 in monotherapy (NCT05006716); the open-label, international, phase 2 study evaluating Sonrotoclax, a next-generation BCL2 inhibitor (NCT05952037).

Conclusions

In conclusion, WM's management has improved over the past decade. To make BTK inhibitor therapy tailored for each person, you should understand the complicated relationship between MYD88 mutations and changes in CXCR4. Because these mutations diminish response rates and progression-free survival, knowing each patient's genetic makeup is crucial for optimal therapy results. The limits of ibrutinib in MYD88 wildtype patients emphasize the need for new therapies. Mutant CXCR4 makes treatment less successful and requires novel BTK inhibitor trials, which could improve combination strategies. One area to explore further is the impact of treatment duration on patient outcomes, comparing immunotherapy with continuous BTK inhibitors. Another aspect to delve into is the varying levels of response seen with different therapies and how this can affect the length of remission or disease management. It would be beneficial to discuss in more detail the potential side effects of these treatments and how they may interact with other existing health conditions in patients. An interesting angle to consider is how personalized therapy plans are developed for each patient based on their circumstances and medical history. Further research could focus on the importance of ongoing monitoring and adjustments to treatment plans as needed based on a patient's response and tolerance to therapy over time.References

- Kumar SK, Callander NS, Adekola K, Anderson LD Jr,

Baljevic M, Baz R, Campagnaro E, Castillo JJ, Costello C, D'Angelo C,

Derman B, Devarakonda S, Elsedawy N, Garfall A, Godby K, Hillengass J,

Holmberg L, Htut M, Huff CA, Hultcrantz M, Kang Y, Larson S, Lee H,

Liedtke M, Martin T, Omel J, Robinson T, Rosenberg A, Sborov D,

Schroeder MA, Sherbenou D, Suvannasankha A, Valent J,

Varshavsky-Yanovsky AN, Snedeker J, Kumar R. Waldenström

Macroglobulinemia/Lymphoplasmacytic Lymphoma, Version 2.2024, NCCN

Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2024

Jan;22(1D):e240001. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2024.0001. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2024.0001 PMid:38244272

- Bibas

M, Sarosiek S, Castillo JJ. Waldenström Macroglobulinemia - A

State-of-the-Art Review: Part 1: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis,

Clinicopathologic Characteristics, Differential Diagnosis, Risk

Stratification, and Clinical Problems. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis.

2024 Jul 1;16(1):e2024061. doi: 10.4084/MJHID.2024.061. https://doi.org/10.4084/MJHID.2024.061 PMid:38984103 PMCid:PMC11232678

- Castillo

JJ, Olszewski AJ, Cronin AM, et al. Survival trends in Waldenstrom

macroglobulinemia: an analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology and

End Results database. Blood 2014;123:3999-4000. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2014-05-574871 PMid:24948623

- Kyle

RA, Benson JT, Larson DR, et al. Progression in smoldering Waldenstrom

macroglobulinemia: long-term results. Blood 2012;119:4462-4466. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2011-10-384768 PMid:22451426 PMCid:PMC3362362

- Kyle

RA, Larson DR, Therneau TM, et al. Long-term follow-up of monoclonal

gammopathy of undetermined significance. N Engl J Med 2018;378:241-249.

https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1709974 PMid:29342381 PMCid:PMC5852672

- Kastritis

E, Morel P, Duhamel A, Gavriatopoulou M, Kyrtsonis MC, Durot E,

Symeonidis A, Laribi K, Hatjiharissi E, Ysebaert L, Vassou A,

Giannakoulas N, Merlini G, Repousis P, Varettoni M, Michalis E, Hivert

B, Michail M, Katodritou E, Terpos E, Leblond V, Dimopoulos MA. A

revised international prognostic score system for Waldenström's

macroglobulinemia. Leukemia. 2019 Nov;33(11):2654-2661. doi:

10.1038/s41375-019-0431-y. Epub 2019 May 22. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-019-0431-y PMid:31118465

- Bustoros

M, Sklavenitis-Pistofidis R, Kapoor P, et al. Progression risk

stratification of asymptomatic Waldenstroom macroglobulinemia. J Clin

Oncol 2019;37:1403-1411. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.19.00394 PMid:30990729 PMCid:PMC6544461

- Kastritis

E, Leblond V, Dimopoulos MA, et al. Waldenstroom's

macroglobulinaemia:ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis,

treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2019;30:860-862. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdy466 PMid:30520968

- Castillo

JJ, Advani RH, Branagan AR, et al. Consensus treatment recommendations

from the tenth International Workshop for Waldenstroom

Macroglobulinaemia. Lancet Haematol 2020;7:e827-837. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30224-6 PMid:33091356

- Pratt

G, El-Sharkawi D, Kothari J, et al. Diagnosis and management of

Waldenstroom macroglobulinemia-a British Society for Haematology

guideline. Br J Haematol 2022;197:171-187. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.18036 PMid:35020191

- Grunenberg

A, Buske C. How to manage waldenström's macroglobulinemia in 2024.

Cancer Treat Rev. 2024 Apr;125:102715. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2024.102715.

Epub 2024 Mar 5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2024.102715 PMid:38471356

- Ghafoor

B, Masthan SS, Hameed M, Akhtar HH, Khalid A, Ghafoor S, Allah HM,

Arshad MM, Iqbal I, Iftikhar A, Husnain M, Anwer F. Waldenström

macroglobulinemia: a review of pathogenesis, current treatment, and

future prospects. Ann Hematol. 2024 Jun;103(6):1859-1876. doi:

10.1007/s00277-023-05345-9. Epub 2023 Jul 6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-023-05345-9 PMid:37414960

- Treon

SP, Cao Y, Xu L, et al. Somatic mutations in MYD88 and CXCR4 are

determinants of clinical presentation and overall survival in

Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. Blood 2014;123:2791-2796. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2014-01-550905 PMid:24553177

- Treon

SP, Tripsas CK, Meid K, et al. Ibrutinib in previously treated

Waldenström's macroglobulinemia. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1430-1440. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1501548 PMid:25853747

- Treon

SP, Gustine J, Meid K, et al: Ibrutinib monotherapy in symptomatic,

treatment-naıve patients with Waldenstroom macroglobulinemia. J Clin

Oncol 36: 2755-2761, 2018 https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2018.78.6426 PMid:30044692

- Castillo

JJ, Meid K, Gustine JN, et al. Long-term follow-up of ibrutinib

monotherapy in treatment-naive patients with Waldenstrom

macroglobulinemia. Leukemia 2022;36:532-539. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-021-01417-9 PMid:34531537 PMCid:PMC8807393

- Sarosiek

S, Gustine JN, Flynn CA, et al. Dose reductions in patients with

Waldenström macroglobulinemia treated with ibrutinib. Br J Haematol

2023;201:897-904. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.18643 PMid:36626914

- Shadman

M, Flinn IW, Levy MY, et al. Zanubrutinib in patients with previously

treated B-cell malignancies intolerant of previous Bruton tyrosine

kinase inhibitors in the USA: a phase 2, open-label, single-arm study.

Lancet Haematol 2023;10:e35-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3026(22)00320-9 PMid:36400069

- Buske

C, Tedeschi A, Trotman J, et al. Ibrutinib Plus Rituximab versus

placebo plus Rituximab for Waldenstr€om's macroglobulinemia: final

analysis from the randomized phase III iNNOVATE study. J Clin Oncol

2022;40:52-62. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.21.00838 PMid:34606378 PMCid:PMC8683240

- Castillo

JJ, Meid K, Gustine JN, et al. Long-term follow-up of ibrutinib

monotherapy in treatment-naive patients with Waldenstrom

macroglobulinemia. Leukemia 2022;36:532-539. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-021-01417-9 PMid:34531537 PMCid:PMC8807393

- Dimopoulos

MA, Tedeschi A, Trotman J, et al. Phase 3 trial of ibrutinib plus

Rituximab in Waldenstroom's macroglobulinemia. N Engl J Med

2018;378:2399-2410. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1802917 PMid:29856685

- Tam

CS, Opat S, D'Sa S, et al. A randomized phase 3 trial of zanubrutinib

vs ibrutinib in symptomatic Waldenstroom macroglobulinemia: the ASPEN

study. Blood 2020;136:2038-2050. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2020006844 PMid:32731259 PMCid:PMC7596850

- Dimopoulos

MA, Opat S, D'Sa S, et al. Zanubrutinib versus ibrutinib in symptomatic

Waldenstroom macroglobulinemia: final analysis from the randomized

phase III ASPEN study. J Clin Oncol 2023;41:5099-5106 https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.22.02830 PMid:37478390 PMCid:PMC10666987

- Rummel

MJ, Niederle N, Maschmeyer G, et al. Bendamustine plus Rituximab versus

CHOP plus Rituximab as first-line treatment for patients with indolent

and mantle-cell lymphomas: an open-label, multicentre, randomized,

phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2013;381:1203-1210. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61763-2 PMid:23433739

- Greil

R, Wupperfeld J, Hinke A, et al. Two years rituximab maintenance vs.

observation after first line treatment with bendamustine plus Rituximab

(B-R) in patients with Waldenstr€om's Macroglobulinemia (MW): Results

of a Prospective, Randomized, Multicenter Phase 3 Study (the StiL NHL7-

2008 MAINTAIN trial). Blood 2019;134(Suppl 1):Abstract 343. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2019-121909

- Treon

SP, Ioakimidis L, Soumerai JD, et al. Primary therapy of Waldenstroom

macroglobulinemia with bortezomib, dexamethasone, and Rituximab: WMCTG

clinical trial 05-180. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:3830-3835. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.20.4677 PMid:19506160 PMCid:PMC2727288

- Dimopoulos

MA, Garcıa-Sanz R, Gavriatopoulou M, et al. Primary therapy of

Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia (WM) with weekly bortezomib,low-dose

dexamethasone, and Rituximab (BDR): long-term results of a phase 2

study of the European Myeloma Network (EMN). Blood 2013;122:3276-3282. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-05-503862 PMid:24004667

- Treon

SP, Tripsas CK, Meid K, et al. Carfilzomib, rituximab, and

dexamethasone (CaRD) treatment offers a neuropathy-sparing approach for

treating Waldenstr€om's macroglobulinemia. Blood 2014;124:503-510. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2014-03-566273 PMid:24859363

- Meid

K, Dubeau T, Severns P, et al. Long-term follow-up of a prospective

clinical trial of carfilzomib, Rituximab and dexamethasone (CaRD) in

Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia. Blood 2017;130(Suppl 1):Abstract 623.

- Castillo

JJ, Meid K, Gustine JN, et al. Prospective clinical trial of ixazomib,

dexamethasone, and Rituximab as primary therapy in Waldenstr€om

macroglobulinemia. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24:3247-3252. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0152 PMid:29661775

- Castillo

JJ, Meid K, Flynn CA, et al. Ixazomib, dexamethasone, and Rituximab in

treatment-naive patients with Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia:long-term

follow-up. Blood Adv 2020;4:3952-3959. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001963 PMid:32822482 PMCid:PMC7448596

- Dimopoulos

MA, Anagnostopoulos A, Kyrtsonis MC, et al. Primary treatment of

Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia with dexamethasone, Rituximab, and

cyclophosphamide. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:3344-3349. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2007.10.9926 PMid:17577016

- Kastritis

E, Gavriatopoulou M, Kyrtsonis MC, et al. Dexamethasone, Rituximab, and

cyclophosphamide as primary treatment of Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia:

final analysis of a phase 2 study. Blood 2015;126:1392-1394. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2015-05-647420 PMid:26359434

- Paludo

J, Abeykoon JP, Kumar S, et al. Dexamethasone, Rituximab and

cyclophosphamide for relapsed and/or refractory and treatment-naïve

patients with Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. Br J Haematol

2017;179:98-105. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.14826 PMid:28786474

- Ioakimidis

L, Patterson CJ, Hunter ZR, et al. Comparative outcomes following CP-R,

CVP-R, and CHOP-R in Waldenstroom's macroglobulinemia. Clin Lymphoma

Myeloma 2009;9:62-66. https://doi.org/10.3816/CLM.2009.n.016 PMid:19362976

- Dimopoulos

MA, Zervas C, Zomas A, Kiamouris C, Viniou NA, Grigoraki V, Karkantaris

C, Mitsouli C, Gika D, Christakis J, Anagnostopoulos N. Treatment of

Waldenström's macroglobulinemia with Rituximab. J Clin Oncol. 2002 May

1;20(9):2327-33. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.09.039. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2002.09.039 PMid:11981004

- Treon SP. How I treat Waldenstr€om macroglobulinemia. Blood 2015; 126:721-732 https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2015-01-553974 PMid:26002963

- Ghobrial

IM, Fonseca R, Greipp PR, et al. Initial immunoglobulin M 'flare' after

rituximab therapy in patients diagnosed with Waldenstrom

macroglobulinemia: an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study.Cancer

2004;101:2593-2598. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.20658 PMid:15493038

- Treon

SP, Branagan AR, Hunter Z, et al. Paradoxical increases in serum IgM

and viscosity levels following Rituximab in Waldenstrom's

macroglobulinemia. Ann Oncol 2004;15:1481-1483. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdh403 PMid:15367407

- Treon

SP, Tedeschi A, San-Miguel J, et al. Report of consensus panel 4 from

the 11th International Workshop on Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia on

diagnostic and response criteria. Semin Hematol 2023;60: 97-106. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.seminhematol.2023.03.009 PMid:37173155

- Dimopoulos

MA, Opat S, D'Sa S,et al. Zanubrutinib Versus Ibrutinib in Symptomatic

Waldenström Macroglobulinemia: Final Analysis From the Randomized Phase

III ASPEN Study. J Clin Oncol. 2023 Nov 20;41(33):5099-5106. doi:

10.1200/JCO.22.02830. Epub 2023 Jul 21. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.22.02830 PMid:37478390 PMCid:PMC10666987

- Owen

RG, McCarthy H, Rule S, et al. Acalabrutinib monotherapy in patients

with Waldenstr€om macroglobulinemia: a single-arm, multicentre,phase 2

study. Lancet Haematol 2020;7:e112-121. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3026(19)30210-8 PMid:31866281

- Treon

SP, Hanzis C, Tripsas C, et al. Bendamustine therapy in patients with

relapsed or refractory Waldenstr€om's macroglobulinemia. Clin Lymphoma

Myeloma Leuk 2011;11:133-135. https://doi.org/10.3816/CLML.2011.n.030 PMid:21454214

- Tedeschi

A, Picardi P, Ferrero S, et al. Bendamustine and rituximab combination

is safe and effective as salvage regimen in Waldenstr€om

macroglobulinemia. Leuk Lymphoma 2015;56:2637-2642. https://doi.org/10.3109/10428194.2015.1012714 PMid:25651423

- Paludo

J, Abeykoon JP, Shreders A, et al. Bendamustine and Rituximab (BR)

versus dexamethasone, Rituximab, and cyclophosphamide (DRC) in patients

with Waldenstr€om macroglobulinemia. Ann Hematol 2018;97: 1417-1425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-018-3311-z PMid:29610969

- Ghobrial

IM, Hong F, Padmanabhan S, et al. Phase II trial of weekly bortezomib

in combination with Rituximab in relapsed or relapsed and refractory

Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:1422-1428.https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.25.3237 PMid:20142586 PMCid:PMC2834499

- Agathocleous

A, Rohatiner A, Rule S, et al. Weekly versus twice weekly bortezomib

given in conjunction with Rituximab, in patients with recurrent

follicular lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma and Waldenstr€om

macroglobulinaemia. Br J Haematol 2010;151:346-353. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08340.x PMid:20880120

- Paludo

J, Abeykoon JP, Kumar S, et al. Dexamethasone, Rituximab and

cyclophosphamide for relapsed and/or refractory and treatment-naïve

patients with Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. Br J Haematol 2017;

179:98-105. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.14826 PMid:28786474

- Kersten

MJ, Amaador K, Minnema MC, et al. Combining ixazomib with subcutaneous

Rituximab and dexamethasone in relapsed or refractory Waldenstr€om's

macroglobulinemia: final analysis of the phase I/II HOVON124/ECWM-R2

study. J Clin Oncol 2022;40:40-51. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.21.00105 PMid:34388022 PMCid:PMC8683241

- Cao

Y, Yang G, Hunter ZR, et al. The BCL2 antagonist ABT-199 triggers

apoptosis, and augments ibrutinib and idelalisib mediated cytotoxicity

in CXCR4 Wildtype and CXCR4 WHIM mutated Waldenstrom macroglobulinaemia

cells. Br J Haematol 2015;170:134-138. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.13278 PMid:25582069

- Castillo

JJ, Allan JN, Siddiqi T, et al. Venetoclax in previously treated

Waldenstr€om macroglobulinemia. J Clin Oncol 2022;40:63-71. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.21.01194 PMid:34793256 PMCid:PMC8683218

- Laszlo

D, Andreola G, Rigacci L, Fabbri A, Rabascio C, Pinto A, Negri M,

Martinelli G. Rituximab and subcutaneous 2-chloro-2'-deoxyadenosine as

therapy in untreated and relapsed Waldenström's macroglobulinemia. Clin

Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2011 Feb;11(1):130-2. doi:

10.3816/CLML.2011.n.029. https://doi.org/10.3816/CLML.2011.n.029 PMid:21454213

- Treon

SP, Branagan AR, Ioakimidis L, et al. Long-term outcomes to fludarabine

and Rituximab in Waldenstr€om macroglobulinemia. Blood

2009;113:3673-3678. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2008-09-177329 PMid:19015393 PMCid:PMC2670786

- Tedeschi

A, Ricci F, Goldaniga MC, et al. Fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and

Rituximab in salvage therapy of Waldenstr€om's macroglobulinemia. Clin

Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2013;13:231-234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clml.2013.02.011 PMid:23490992

- Tedeschi

A, Benevolo G, Varettoni M, et al. Fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide

and Rituximab in Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia: an effective but

myelosuppressive regimen to be offered to patients with advanced

disease. Cancer 2012;118:434-443 https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.26303 PMid:21732338

- Ghobrial

IM, Witzig TE, Gertz M, et al. Long-term results of the phase II trial

of the oral mTOR inhibitor everolimus (RAD001) in relapsed or

refractory Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. Am J Hematol 2014;89:237-242.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.23620 PMid:24716234

- Kyriakou

C, Canals C, Cornelissen JJ, et al. Allogeneic stem-cell

transplantation in patients with Waldenstr€om macroglobulinemia: report

from the Lymphoma Working Party of the European Group for Blood and

Marrow Transplantation. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:4926-4934. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.27.3607 PMid:20956626

- Kyriakou

C, Canals C, Sibon D, et al. High-dose therapy and autologous stem-cell

transplantation in Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia: the Lymphoma Working

Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. J

Clin Oncol 2010;28:2227-2232. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.24.4905 PMid:20368570

- Palomba,

M.L., Qualls, D., Monette, S., Sethi, S., Dogan, A., Roshal, M.,

Senechal, B., Wang, X., Rivière, I., Sadelain, M., Brentjens, R.J.,

Park, J.H., Smith, E.L., 2022 Feb. CD19-directed chimeric antigen

receptor T cell therapy in Waldenström macroglobulinemia: a preclinical

model and initial clinical experience. J. Immunother. Cancer 10 (2),

e004128. https://doi.org/10.1136/jitc-2021-004128 PMid:35173030 PMCid:PMC8852764

- Owen,

R.G., Bynoe, A.G., Varghese, A., et al., 2011. Heterogeneity of

histological transformation events in Waldenström's macroglobulinemia

(WM) and related disorders. Clin.Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 11, 176e179 https://doi.org/10.3816/CLML.2011.n.042 PMid:21856554

- Durot,

E., Tomowiak, C., Michallet, A.-S., Dupuis, J., Hivert, B., Leprêtre,

S., et al., 2017. Transformed Waldenström macroglobulinemia: clinical

presentation and outcome. A multi-institutional retrospective study of

77 cases from the French Innovative Leukemia Organization (FILO). Br.

J. Haematol. 179, 439e448. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.14881 PMid:28770576

- Durot,

E., Kanagaratnam, L., Zanwar, S., Kastritis, E., D'Sa, S., Garcia-Sanz,

R., et al., 2020. A prognostic index predicting survival in transformed

Waldenström macroglobulinemia. Haematologica. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2020.262899 PMid:33179472 PMCid:PMC8561274

- Castillo,

J.J., Olszewski, A.J., Hunter, Z.R., et al., 2015b. Incidence of

secondary malignancies among patients with Waldenstrom

macroglobulinemia: an analysis of the SEER database. Cancer 121,

2230e2236. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29334 PMid:25757851

- Castillo,

J.J., Olszewski, A.J., Kanan, S., et al., 2015c. Survival outcomes of

secondary cancers in patients with Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia: an

analysis of the SEER database. Am. J. Hematol. 90, 696e701 https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.24052 PMid:25963924

- Castillo

JJ, Itchaki G, Paludo J, et al. Ibrutinib for the treatment of Bing-

Neel syndrome: a multicenter study. Blood 2019;133:299-305. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2018-10-879593 PMid:30523119

- Castillo

JJ, D'Sa S, Lunn MP, et al. Central nervous system involvement by

Waldenström macroglobulinemia (Bing-Neel syndrome): a

multi-institutional retrospective study. Br J Haematol 2016;172:

709-715. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.13883 PMid:26686858 PMCid:PMC5480405

- Simon L, Fitsiori A, Lemal R, et al. Bing-Neel syndrome, a rare complication of Waldenstr€om macroglobulinemia: analysis of 44 cases and review of the literature. A study on behalf of the French Innovative Leukemia Organization (FILO). Haematologica 2015;100: 1587-1594 https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2015.133744 PMid:26385211 PMCid:PMC4666335