We performed a retrospective analysis on 228 oncohematologic patients treated with DOACs for AF or VTE in our center between January 2012 and April 2024. DOAC therapy was started if platelet count was > 50x109/L, creatinine clearance was≥ 15 mL/min, and liver function was normal. DOAC dosage was adjusted for renal function or body weight, as per guidelines.[4-5] DOACs were administered at full dose for AF and for the acute phase of VTE, while a low-dose (apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily or rivaroxaban 10 mg daily) was administered as secondary prophylaxis of VTE in the extended-phase treatment in patients with active onco-hematologic disease or persistence of residual VTE, according to the previous experience of our group.[6] Dabigatran was administered only in patients affected by AF. After patients were started on DOAC, they were evaluated at 1, 3, and 6 months; then, follow-up visits were performed every 6 months until the eventual discontinuation of anticoagulation or if clinically indicated. At these time points, the patients were evaluated for complete blood count, liver and renal function, bleeding (B-AE), and thrombotic (T-AE) adverse events. Bleeding complications were divided into major (MB), clinically relevant non-major (CRNMB), and minor bleeding as per International Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis (ISTH) guidelines.[7]

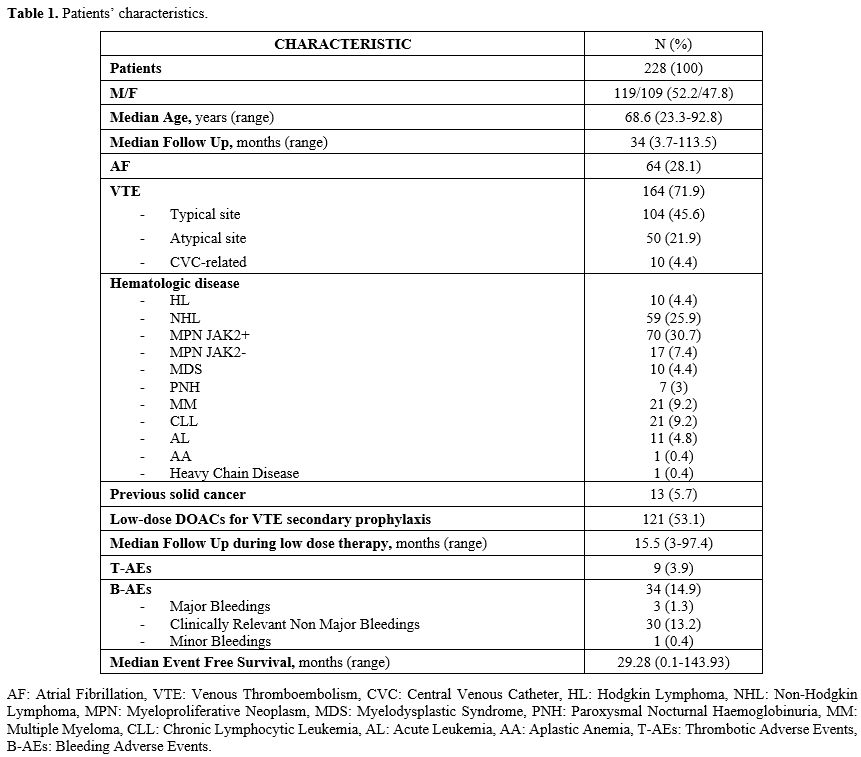

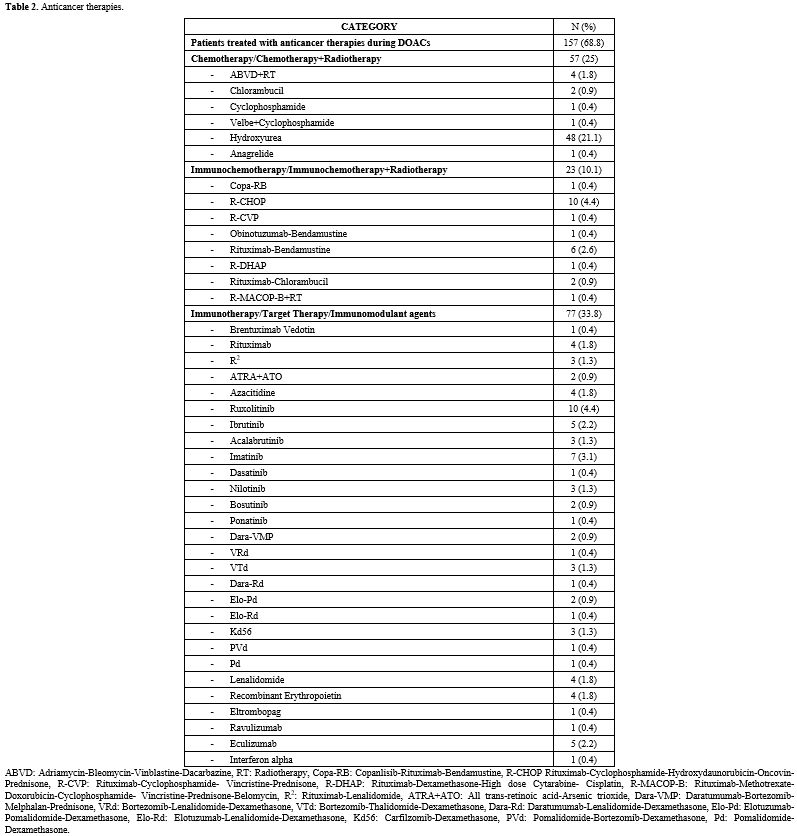

Patients’ characteristics are resumed in Table 1 and Table 2.

|

Table 1. Patients’ characteristics. |

|

Table 2. Anticancer therapies. |

Median age at DOAC start was 68.6 years (range 23.3-92.8); 119 (52.2%) patients were males, 109 (47.8%) females. Patients were affected by the following onco-hematologic diseases: 70 (30.7%) JAK2-positive myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN JAK2+), 59 (25.9%) NHL, 21 (9.2%) chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), 21 (9.2%) MM, 17 (7.5%) JAK2-negative myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN JAK2-), 11 (4.8%) acute leukemia (AL), 10 (4.4%) HL, 10 (4.4%) myelodysplastic neoplasms (MDS), 7 (3.1%) paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH), 1 (0.4%) aplastic anemia (AA), 1 (0.4%) heavy chain disease. Thirteen patients (5.7%) had a history of solid cancer. One hundred fifty-seven patients (68.9%) were concomitantly treated with DOACs and antineoplastic therapy: 77 (33.8%) immunotherapy, target therapy or immunomodulant agents, 57 (25%) chemotherapy or chemotherapy plus radiotherapy (CHT/CHT+RT), 23 (10.1%) immunochemotherapy or immunochemotherapy plus radiotherapy (iCHT/iCHT+RT). The reason for anticoagulation was VTE in 164 (71.9%) cases and AF in 64 (28.2%). The DOACs administered at full dose were apixaban in 105 patients (46.1%), edoxaban in 63 (28.1%), rivaroxaban in 53 (23.2%), dabigatran in 6 (2.6%). One hundred twenty-one patients (54.3%) were switched to low-dose DOACs prophylaxis after the acute phase of VTE (median 8.43 months, range 3-100.1): 72 (31.6%) low-dose apixaban and 49 (21.5%) low-dose rivaroxaban, according to the previous experience of our group.[6] The median follow-up of full-dose DOACs was 34 months (range 3.7-113.5); the median follow-up during low-dose DOAC treatment was 15.5 months (range 3-97.4). The median EFS of the entire study population was 29.28 months (range 0.1-143.93). At the beginning of treatment, the median cell blood count values were: hemoglobin 12.9 g/dL (range 7.7-17.3), white blood cells 6.2x109/L (range 0.830-380), platelets 223x109/L (55-1,200). During DOAC therapy, 28 patients reached a platelet count < 100 x109/L; among them, 10 reached platelet levels < 50x109/L during the concomitant antineoplastic therapy (5 LNH, 3 MM, 1 MPN JAK2-, 1 AL). In this latter group, 6 patients discontinued full dose DOAC therapy, then were treated with LMWH (100 U/Kg/day) and, finally, resumed DOAC therapy (5 at full- and 1 at low-dose) when platelets count returned > 50 x109/L. Among the other 4 patients, 3 permanently discontinued anticoagulation (2 LNH, 1 AL) for persistent thrombocytopenia, and one affected by NHL was switched to fondaparinux and never resumed DOACs therapy.

We have not observed significant variations in terms of transaminase levels or creatinine since DOACs started.

During follow-up, 34 (14.9%) B-AEs [3 MBs (1.3%), 30 CRNMBs (13.2%) and 1 minor bleeding (0.4%)] and 9 (3.9%) T-AEs occurred, namely 5 B-AEs per 100 patient-years (0.4 MBs per 100 patient-years) and 1.4 T-AEs per 100 patient-years. Two patients had both a hemorrhagic and thrombotic event.

Three MBs were reported during full-dose therapy. One MB occurred in a patient affected by AF (B-EFS 9.61 months) treated with apixaban and was managed with a permanent switch to low-dose DOAC therapy.[6] A second MB occurred in a VTE patient in therapy with rivaroxaban (B-EFS 0.92 months), who was also permanently switched to low-dose treatment. The third MB was a cerebral hemorrhage, which occurred during full-dose edoxaban therapy (B-EFS 13.02 months); anticoagulation was withheld for 14 days, then the patient was switched to LMWH and, finally, after 4 weeks, to low-dose rivaroxaban. Ten days later, he was diagnosed with a pulmonary embolism (PE), and therapy with fondaparinux 7.5 mg was started; after one year of fondaparinux and complete resolution of PE, the therapy was switched to low-dose apixaban as secondary prophylaxis of VTE.

Among the 30 patients who developed CRNMBs, 2 (0.9%) permanently discontinued DOAC therapy for persistent gastrointestinal bleeding and were switched to LMWH; one of them suffered from chronic inflammatory bowel disease.

One minor B-AE, a conjunctival hemorrhage, was reported in a patient during low-dose apixaban, and it was managed with a temporary therapy discontinuation for two days.

Regarding T-AEs, eight cases were of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and one pulmonary embolism (PE). Six cases (2.6%) occurred in patients treated with full-dose DOACs (1 for AF and 5 for a previous VTE event) and 3 cases (1.3%) during secondary antithrombotic prophylaxis with low-dose DOACs. After T-AE diagnosis, the patient with AF was switched from edoxaban 60 mg daily to dabigatran 150 mg twice a day. Among the 5 patients treated with full-dose DOACs for a previous VTE, 2 were switched to acenocoumarol, and 3 were temporarily switched to LMWH 100 UI/kg twice daily. After one month of LMWH, full-dose therapy with a different DOAC was resumed. Among the 3 patients with T-AEs during secondary prophylaxis with low-dose DOACs, 2 were switched to full-dose of the same DOAC, and the other one, in consideration of the previously mentioned cerebral hemorrhage, was permanently switched to fondaparinux.

At chi-square analysis, there was no statistically significative difference between patients treated with DOACs for AF or VTE (p=0.16), neither between patients with different oncohematologic diseases in terms of AEs (p=0.36), B-AEs (p=0.94)or T-AEs (p=0.84).

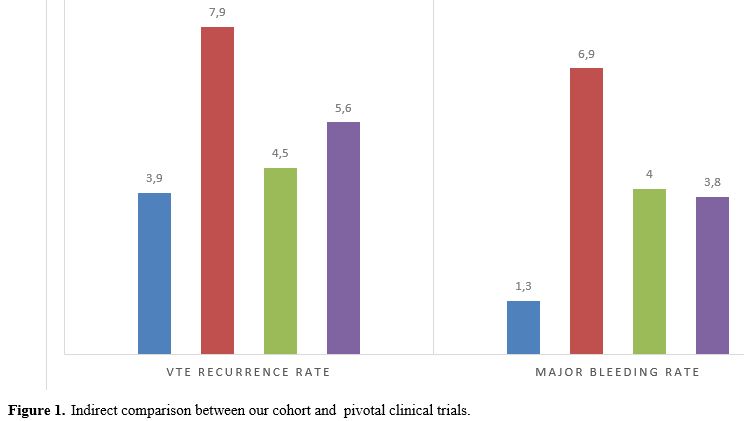

In our cohort, the rate of VTE recurrences (3.9%) and major bleeding complications (1.3%) were comparable to those of the pivotal clinical trials on the use of DOACs in cancer patients: a VTE recurrence rate of 4.5% was reported in the Select-D trial, in the Hokusay-VTE Cancer trial the rate was 7.9% and in the Caravaggio trial 5.6%. MBs rate was 4% in the Select-D trial, 6.9% in the Hokusay-VTE Cancer trial, and 3.8% in the Caravaggio trial[1-3] (Figure 1).

The principal limitation of our analysis is that, due to the sample size, a study by disease subgroups is not possible, considering the different thrombotic and hemorrhagic risks of onco-hematological diseases (e.g., MPN and AL).

Henceforth, with the limits of a retrospective analysis, DOACs for secondary prophylaxis of VTE, prevention of stroke and systemic thromboembolism in AF, and VTE therapy seem safe and effective in the once-hematologic setting.

References

- Raskob G.E., van Es N., Verhamme P. et al.; Hokusai

VTE Cancer Investigators. " Edoxaban for the Treatment of

Cancer-Associated Venous Thromboembolism." N Engl J Med. 2018 Feb

15;378(7):615-624.

- Young

A.M., Marshall A., Thirlwall J. et al. " Comparison of an Oral Factor

Xa Inhibitor With Low Molecular Weight Heparin in Patients With Cancer

With Venous Thromboembolism: Results of a Randomized Trial (SELECT-D)."

J Clin Oncol. 2018 Jul 10;36(20):2017-2023.

- Agnelli

G., Becattini C., Meyer G. et al.; Caravaggio Investigators. " Apixaban

for the Treatment of Venous Thromboembolism Associated with Cancer." N

Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 23;382(17):1599-1607. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1915103 PMid:32223112

- Kearon

C., Akl E.A., Ornelas J. et al. "Antithrombotic therapy for VTE

disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report." Chest.

2016;149:315-352 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.026 PMid:26867832

- Steffel

J., Verhamme P., Potpara T.S. et al. " The 2018 European heart rhythm

association practical guide on the use of non-vitamin K antagonist oral

anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation: executive

summary." Europace. 2018;20(8):1231-1242. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euy054 PMid:29562331

- Laganà

A., Assanto G.M., Masucci C., Passucci M., Donzelli L., Serrao A.,

Baldacci E., Santoro C., Chistolini A.Secondary prophylaxis of venous

thromboembolism (VTE) with low dose apixaban or rivaroxaban: results

from a patient population with more than 2 years of median follow-up.

Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2024, 16(1): e2024020 https://doi.org/10.4084/MJHID.2024.020 PMid:38468835 PMCid:PMC10927198

- Kaatz S., Ahmad D., Spyropoulos A.C. et al. " Definition of clinically relevant non-major bleeding in studies of anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation and venous thromboembolic disease in non-surgical patients: communication from the SSC of the ISTH." J Thromb Haemost. 2015 Nov;13(11):2119-26. https://doi.o rg/10.1111/jth.13140 PMid:26764429