To the editor

Acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is a multisystem disorder that may occur as a complication of haematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT). In cases of acute cutaneous GVHD that are particularly severe, patients may develop lesions that are not typical for the condition, as well as generalised erythroderma, vesicle, bullae or extensive skin breakdown. These symptoms may resemble those of Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) or toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). The collective impact of dermatological, hepatic, and gastrointestinal manifestations are used to categorise the overall severity (grade) of acute GVHD. The existence of erythroderma and bullae (as may present in SJS/TEN-like acute cutaneous GVHD) is adequate for diagnosing grade 4 GVHD and is linked to an unfavourable prognosis.[1]In cases of stage 2 and above acute GVHD, the use of a systemic corticosteroid represents the optimal treatment approach over alternative methods. On days 5 and 7 of steroid therapy, the patient's acute GVHD status is reassessed to determine whether steroid resistance has developed.

This case study presents a case of steroid-resistant SJS/TEN-like acute cutaneous GVHD, which demonstrated a successful response to ruxolitinib.

Case

This case report describes a 34-year-old male with AML, intermediate risk, initially treated with standard 7+3 (Cytarabine + Daunorubicin) induction chemotherapy followed by high-dose cytarabine consolidation. Despite achieving medullary remission, minimal residual disease(MRD) persisted. The patient underwent allogeneic HSCT from an HLA-matched sibling donor, and no GvHD was observed after this transplantation. At 33rd-month post-transplant, the patient, with full donor chimerism, developed a pituitary macroadenoma and hypopituitarism, as well as a central nervous system (CNS) relapse but medullary remission, which was confirmed in the bone marrow. Management included cranial radiotherapy and pituitary hormone replacement.Subsequent bone marrow relapse was treated with salvage chemotherapy (High-dose Cytarabine + Mitoxantrone), achieving medullary remission. Persistent CNS disease necessitated intrathecal triple therapy (Dexamethasone + Cytarabine + Methotrexate) until cerebrospinal fluid clearance. MRI response was also obtained.

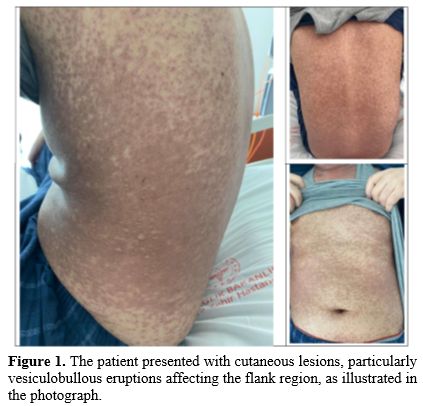

A second allogeneic HSCT was performed from the same HLA-matched sibling donor using a myeloablative FLU-TBI conditioning regimen. GvHD prophylaxis consisted of Cyclosporine-A and Methotrexate. Neutrophil engraftment was achieved on day 8, and platelet engraftment was achieved on day 11. On post-transplant day 25, the patient presented with severe cutaneous manifestations with some vesiculobullous lesions initially suspected as aGvHD or drug eruptions (Figure 1). The patient’s current medications were reviewed due to a suspected drug-related reaction, and the most likely causative agent, TMP/SMX, used for PJP prophylaxis, was discontinued.

|

|

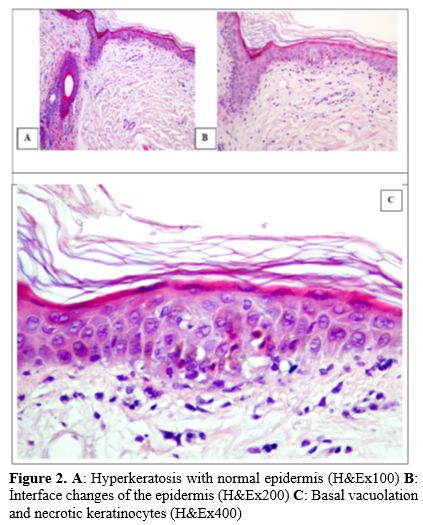

The patient was initiated on a dose of corticosteroid (2 mg/kg methylprednisolone) as a primary treatment. The dermatological evaluation led to the administration of IVIG at a dose of 1 g/kg/day for the first 3 days upon suspicion of SJS. However, due to the lack of response to corticosteroid and IVIG therapies, ruxolitinib (10 mg twice daily) was added to the treatment regimen after the first week. The skin biopsy report indicated grade 2 GVHD (Figure 2).

|

|

Significant clinical improvement was observed within one week of ruxolitinib initiation, and a complete response was observed at the fourth week of treatment (Figure 3).

Corticosteroids were tapered over six weeks to physiological replacement doses. Ruxolitinib was continued for 56 days before gradual discontinuation.

Cyclosporine was maintained with target trough levels of 150-250 ng/mL and discontinued on day +90 post-transplant.

The patient is currently being followed as an outpatient with complete remission of cutaneous GvHD in the sixth month of the second allogeneic stem cell transplantation.

Discussion

In the absence of accompanying extracutaneous manifestations, establishing a definite diagnosis of acute cutaneous GVHD may prove challenging. The clinical picture of acute cutaneous GvHD is non-specific and may prove challenging to distinguish from other dermatological conditions that occur in patients undergoing haematopoietic cell transplantation, particularly drug reactions. Additionally, there are no distinctive histopathological features that can be used to diagnose this condition with certainty.[2]A retrospective analysis of patients with acute cutaneous GVHD; SJS/TEN-like features (n = 15) or without these features (n = 16) revealed a higher incidence of systemic complications, including haematological abnormalities, hepatitis, diarrhea, renal dysfunction, and bacteremia, in patients with SJS/TEN-like acute cutaneous GvHD. Furthermore, patients with SJS/TEN-like aGVHD demonstrated reduced 2-month survival rates and a 5.35-fold increase in 5-year mortality compared to those with non-SJS/TEN-like aGVHD.[3] The mortality rate of patients with SJS/TEN-like aGVHD during the whole follow-up period was 80%, significantly higher than the 25% in patients with non-SJS/ TEN-like aGVHD. aGVHD with TEN-Like features is found also in pediatric patients who have the same poor outcome from standard therapy.[4] Recently it has been reported that a child with steroid resistant SJS/TEN-like aGVHD obtained complete response to ruxolitinib.[5]

Systemic corticosteroids constitute the standard initial medical treatment for patients presenting with grade ≥2 aGVHD.[6] The use of systemic corticosteroids for the treatment of grade ≥2 aGVHD is widespread, with no other regimen having been proven to be superior.

Treatment is generally initiated with methylprednisolone at a dose of 2 mg/kg/day, administered in divided doses, and continued for several weeks in patients responding to aGVHD.[7] Progression of GVHD by day 5 or lack of response by day 7, as observed in our case, is indicative of steroid-resistant GVHD.

For steroid-resistant aGVHD, treatment with ruxolitinib is recommended over other agents due to its demonstrated superior efficacy and favorable toxicity profile in a phase 3 trial comparing ruxolitinib to the best available therapy (BAT). In this trial, 309 patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive ruxolitinib (10 mg orally, twice daily) or the investigator's choice of therapy. At day 28, ruxolitinib demonstrated a superior overall response rate (62% vs. 39%) and complete response (34% vs. 19%) compared with the control group.[8]

This case highlights the diagnostic challenges in differentiating aGVHD from SJS/TEN-like presentations in the post-HSCT setting. Diagnosis of aGVHD in this patient was supported by the patient's resistance to steroids and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), the pathological findings consistent with GVHD, and the positive therapeutic response to ruxolitinib.

In conclusion, this case highlights the importance of rapid intervention and the potential efficacy of JAK inhibitors in steroid-resistant cutaneous GVHD. This case highlights the critical importance of rapid intervention and decision-making in suspected aGVHD, as timely treatment can significantly influence prognosis, morbidity, and mortality.

References

- Przepiorka D, Weisdorf

D, Martin P, Klingemann HG,

Beatty P, Hows J, Thomas ED. 1994 Consensus Conference on Acute GVHD

Grading. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995 Jun;15(6):825-8. PMID: 7581076.

- Mays

SR, Kunishige JH, Truong E, Kontoyiannis DP, Hymes SR. Approach to the

morbilliform eruption in the hematopoietic transplant patient. Semin

Cutan Med Surg. 2007 Sep;26(3):155-62. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2007.09.004.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sder.2007.09.004

PMid:18070682

- Hung

YT, Chen YW, Huang Y, Lin YJ, Chen CB, Chung WH. Acute

graft-versus-host disease presenting as Stevens-Johnson syndrome and

toxic epidermal necrolysis: A retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad

Dermatol. 2023 Apr;88(4):792-801. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2022.10.035. Epub

2022 Oct 22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2022.10.035

PMid:36280000

- Sheu

Song J, Huang JT, Fraile Alonso MDC, Antaya RJ, Price HN, Funk T,

Francois RA, Shah SD. Toxic epidermal necrolysis-like acute

graft-versus-host disease in pediatric bone marrow transplant patients:

Case series and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2022

Nov;39(6):889-895. doi: 10.1111/pde.15069 https://doi.org/10.1111/pde.15069

PMid:35730149

- Marlowe

E, Palmer R, Rahrig AL, Dinora D, Harrison J, Skiles J, Rahim MQ. Case

report: Toxic epidermal necrolysis as a unique presentation of acute

graft versus host disease in a pediatric patient. Front Immunol. 2025

Jan 23;15:1452245. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1452245 https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1452245

PMid:39916964 PMCid:PMC11798950

- Dignan

FL, Clark A, Amrolia P, Cornish J, Jackson G, Mahendra P, Scarisbrick

JJ, Taylor PC, Hadzic N, Shaw BE, Potter MN; Haemato-oncology Task

Force of British Committee for Standards in Haematology; British

Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Diagnosis and management

of acute graft-versus-host disease. Br J Haematol. 2012

Jul;158(1):30-45. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2012.09129.x. Epub 2012 Apr

26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2012.09129.x

PMid:22533831

- Deeg

HJ. How I treat refractory acute GVHD. Blood. 2007 May

15;109(10):4119-26. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-041889. Epub 2007 Jan

18. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2006-12-041889

PMid:17234737 PMCid:PMC1885485

- Zeiser R, von Bubnoff N, Butler J, Mohty M, Niederwieser D, Or R, Szer J, Wagner EM, Zuckerman T, Mahuzier B, Xu J, Wilke C, Gandhi KK, Socié G; REACH2 Trial Group. Ruxolitinib for Glucocorticoid-Refractory Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease. N Engl J Med. 2020 May 7;382(19):1800-1810. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1917635. Epub 2020 Apr 22. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1917635 PMid:32320566