In contrast, most non-transplant eligible patients are non-frail and will be likely to benefit from the drugs available for transplant-eligible patients.[6,7] This reflects the fact that the elderly population is very heterogeneous, with several differences in biological or physical characteristics. Indeed, despite the significant advancements in the treatment landscape of MM over the last years, resulting in improvements in outcomes and quality of life, MM remains an incurable disease, and challenges such as drug resistance and relapse or treatment-related adverse events still exist. Nevertheless, the positive impact of novel drugs on survival for older patients is more limited compared to younger and fit patients. Considering the wide variations in their baseline fitness and performance status, the optimal management of non-transplant eligible patients with MM has long been a challenge; it requires an individualized therapeutic approach that is based on biologic rather than chronologic age. The introduction of several novel drugs has allowed deeper and more durable responses in non-transplant eligible patients and, as for transplant eligible patients, the achievement of complete response (also with minimal residual disease negative, MRD) could be translating into a better outcome in terms of progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS), including patients with age more than 75.[8-10] The optimal choice of treatment regimen should consider not only specific disease-related factors (such as disease stage, cytogenetic risk, and functional disease risk) but also patients-related factors, for example, the baseline organ function, the underlying comorbidities, the presence of symptoms that specific therapies could aggravate; the presence of caregiver and the prediction of adherence to therapy. In this heterogeneous population, it is fundamental to balance the efficacy and safety of combination therapy in order to avoid the negative impact of premature treatment discontinuation on outcomes. It is also important to consider supportive care in association with antimyeloma therapy to control disease-related signs and symptoms. As the treatment landscape for MM therapy continues to expand also in the setting of non-transplant eligible patients rapidly, the optimal approach for older and frail patients has not been clearly defined and has become increasingly challenging. First, this group of non-transplant eligible patients is underrepresented in clinical trials due to stringent eligibility criteria that often exclude these patients and, consequentially, could be undertreated in real-world practice.[11,12] However, some recent phase III trials involving non-transplant eligible patients have included a frailty sub-analysis to help physicians optimize the management of these patients.

Frailty Definition

Frailty is an important topic in the field of MM,[13,14] but unfortunately, there is still no standard definition.[15-17] A key concept is that frailty is not synonymous with aging because not all older adults are frail, and not all frail individuals are elderly. However, advancing age is associated with increased vulnerability.[14,18] In contrast to the natural aging process, frailty is generally considered to be at least partially reversible and amenable to intervention.[19] Recognizing frailty should be an essential aspect of any medical assessment, particularly when invasive interventions or potentially harmful medications are being considered. A frailty-based approach can help to balance the risks and benefits of any treatment. A failure to recognize frailty status can lead to patients being exposed to interventions that may not benefit them and may even harm them. Conversely, excluding physiologically healthy (non-frail) older patients on the basis of age alone may lead to undertreatment.[20] Defining and stratifying frailty helps clinicians define treatment goals based on the patient's vulnerability and establish tailored treatment.[13] Fit patients should receive treatments aimed at deep remission, while patients with intermediate fitness should receive a balance of efficacy and tolerability. Frail patients require a more conservative approach that focuses on minimizing toxicity. Identifying frail individuals who are approaching the end of life (end-stage frailty) can be challenging due to unpredictable functional decline. Frailty is a condition characterized by a state of vulnerability and carries an increased risk of adverse health outcomes and/or mortality when exposed to stressors.[6,15,18,19] The European Union has placed emphasis on the definition of frailty because frail people are significant users of community resources, hospitalized and admitted to nursing homes. Early intervention with frail people is likely to improve quality of life and reduce healthcare costs. Frailty can be physical, psychological, or a combination of both, and it is dynamic, meaning that it can improve or worsen over time. Our understanding of the biological mechanisms underlying frailty is constantly evolving. Processes that accelerate aging at the cellular and subcellular level, such as chronic inflammation, cellular senescence, mitochondrial dysfunction, and impaired nutrient sensing, are thought to contribute to multiple system dysfunctions leading to clinical manifestations of frailty. Investigating whether interfering with these biological processes can prevent or reverse frailty is a current research focus.[21] Currently, two major conceptual frameworks for frailty have influenced the development of various measurement tools:[16,18,19]- Physical frailty (phenotypic or syndromic frailty)[17] is characterized by signs and symptoms (e.g., fatigue, low physical activity, weakness, weight loss, slow gait) in community-dwelling older adults who are most vulnerable to adverse outcomes. The degree of frailty is determined by the number of characteristics present: Individuals are considered "robust" if no characteristics are present, "prefrail" if one or two characteristics are present, and "frail" if three to five characteristics are present. The presence of all five characteristics indicates a critical stage, which is associated with a significant increase in mortality risk and reduced reversibility.

- Deficit accumulation frailty or index frailty[11] is based on the cumulative effect of individual deficits. In this model, the presence or absence of various factors (e.g., low mood, tremor) must be calculated as a proportion of the total number of possible deficits. The principle of this approach is that the more individual deficits are present, the more likely it is that the person is frail. These deficits include symptoms, signs, disabilities, diseases, and laboratory results.

In both models, advanced frailty indicates an increased risk of poor homeostatic resolution following stress, increasing the risk of outcomes such as falls, delirium, and disability. Despite the call for a standardized definition of frailty, these two approaches continue to coexist.

Because frailty increases the vulnerability of older patients to treatment-related risks, an objective assessment of this condition is essential to preserve physiologic reserves and avoid stressors to maximize functional capacity and quality of life, consistent with the patient’s goals and degree of frailty.[13] High-yield clinical goals include depression, anemia, hypotension, hypothyroidism, vitamin B12 deficiency, unstable medical conditions, and adverse drug reactions.

A quantitative definition of frailty status relies on a comprehensive medical assessment or geriatric assessment, which should be performed to identify triggers and contributing factors and determine intervention targets. An important part of management is to make routine care safer for frail patients. Frailty should not be a justification for withholding effective treatments but should guide patient-centered care. Matching treatment to the patient’s health priorities can reduce the burden of treatment and prevent unnecessary care.[21] Despite the limitations of frailty, individualized, adaptive strategies, such as maintaining daily routines in familiar surroundings, encouraging social contact, and mobilizing resources, can support self-care and maintain social roles.

Management in these cases should focus on comfort and dignity through palliative and hospice care. Despite the recognized importance of defining frailty status, the use of specific scores has not yet been fully established in routine clinical practice.[14]

These tools can be confusing due to discrepancies between methods,[16] resulting in different treatment plans for similar patients or being too time-consuming for busy clinics.

The results of clinical trials often do not reflect real-world practice,[20] as trial participants are usually a highly selected group, and vulnerable patients are underrepresented in the clinical setting.

a) Currently available fitness assessment tools and scores. In MM, overtreatment of frail patients and undertreatment of healthy elderly patients are both clinical challenges that can lead to lower survival and quality of life (QoL).[13]

Consequently, it is critical to strike a balance between treatment efficacy and toxicity to achieve meaningful, sustained remission while preserving the patient's quality of life. Several frailty scores exist to assess patient fitness, although a universally standardized frailty score has not yet been established.[23]

Assessing the fitness of MM patients serves several important purposes:

a. Detection of frailty and sarcopenia: MM often leads to muscle wasting and loss of function, which increases the risk of falls, fractures, and reduced quality of life. Early detection of frailty and sarcopenia enables timely interventions to reduce these risks.

b. Predicting treatment response and survival: Fitness levels can influence treatment tolerance and response. Patients with better baseline fitness may have fewer treatment-related side effects and better survival prospects.

c. Monitoring treatment-related side effects: Certain MM therapies can cause fatigue, muscle weakness, and other physical impairments. Regular fitness assessments can help monitor these side effects and adjust treatment plans.

Tailored exercise interventions: Personalized exercise programs can be developed based on individual fitness levels to optimize benefits and minimize risks.

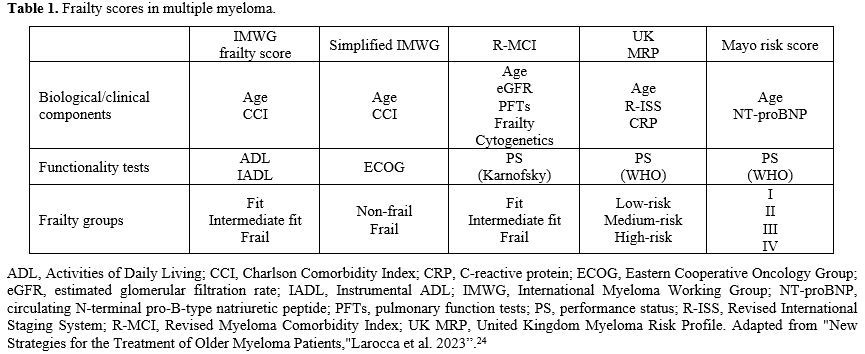

The International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) Frailty Index represents the first specific frailty assessment tool developed for patients with MM and the most used in daily routine. This score originally comprised three assessment tools: the Katz Activities of Daily Living (ADL), the Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL), and the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI).[25] These scores were retrospectively evaluated in patients with MM.[15] In terms of predictive power of outcome, the IMWG Frailty Index showed a 3-year overall OS rate of 84% in fit patients, 76% in patients with intermediate fitness, and 57% in frail patients after a median follow-up of 18 months, regardless of staging and treatment received. PFS rates at 3 years were 48% in fit patients, 41% in patients with intermediate fitness, and 33% in frail patients. A Cox model confirmed these results. Frailty profile was associated with an increased risk of mortality, disease progression, non-hematologic adverse events, and treatment discontinuation, regardless of ISS stage, chromosomal abnormalities, or treatment type.[7] Recently, the IMWG frailty score was modified and transformed into a new score, defined as the Simplified Frailty Scale, which includes only three variables: age, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, and the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), which allow to define two populations: frail and non-frail.[25]

The IMWG Frailty Score and the Simplified Frailty Scale show limited agreement and some degree of discordance in defining frail and unfit patients, increasing the potential for misclassification and complicating comparisons in the existing literature on frail MM patients. Despite these inconsistencies, the Simplified Frailty Scale can be a useful screening tool, particularly when patient-reported performance status is used.[25]

Other tools, such as the Revised Myeloma Comorbidity Index (R-MCI), the Mayo Risk Score, and the UK Myeloma Research Alliance Risk Profile, have also been introduced as effective clinical assessment scales.[23]

In particular, the R-MCI has been evaluated in a large cohort of over 1500 MM patients and comprises five major risk factors selected from 12 carefully assessed comorbidities using a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model. The main risk factors in the R-MCI are impaired renal function (measured by estimated glomerular filtration rate or eGFR), lung function, Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS), advanced age, and frailty according to the Fried criteria. The Fried criteria define frailty as a clinical syndrome characterized by the presence of three or more of the following: unintentional weight loss (10 pounds within the past year), self-reported fatigue, decreased grip strength (weakness), slow walking speed, and low physical activity.[17] If available, cytogenetic information can also be included in the R-MCI. Patients can be scored with up to nine points, which categorize them into 3 risk groups: fit (0–3 points), moderately fit (4–6 points), and frail (7–9 points). These groups show significant differences in Kaplan–Meier curves for PFS and OS, as well as different rates of treatment-related mortality (TRM) and risk of complications or adverse events.[23] The R-MCI offers advantages such as accurate assessment of the patient's physical condition and ease of use in the clinical setting.[26]

Although geriatric assessments have been shown to be reliable for assessing patient's physical and mental status, they can be difficult to integrate into routine clinical practice due to their time-consuming nature. Therefore, shorter and more objective assessments of frailty have been proposed, including the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test, handgrip strength, the Short Physical Performance Battery, or self-reported measures such as the Katz Basic Activities of Daily Living (ADL) scale, Lawton, and Brody's Instrumental ADL (IADL), the Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI), and the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36/12. Although these assessments provide more objective and self-reported measures of patient fitness, they are not specific to MM and have been used less frequently in this context.

Currently, objective markers of frailty and senescence are not well defined, and it remains to be determined which markers can be reliably incorporated into clinical practice to identify potential risks. There is an urgent clinical need for more prospective studies that incorporate frailty scores and geriatric assessments into antimyeloma therapies, as well as a broader range of multicenter clinical trials that include older patients with MM and various comorbidities. Such studies should clarify the extent to which patient and disease management in MM has truly improved and what further steps can be taken to improve these outcomes in the future.[7,23]

In addition, it is advisable to revise approaches to reporting tolerability and quality of life. Tolerability analyzes should be standardized across studies and include not only the most serious events but also minor events, as some of them have a significant impact on quality of life and clinical outcomes. In addition, a more thorough assessment of quality of life would be beneficial.[27]

b) New strategies for assessing frailty in patients with multiple myeloma. Traditional methods of assessing fitness, such as self-report questionnaires and simple physical performance tests, fail to adequately capture the complexity of fitness in MM patients.[28]

Newer strategies offer more comprehensive and objective assessments:

- Nutritional assessment, which evaluates nutritional status and identifies any nutritional deficiencies (Mini Nutritional Assessment MNA or its abbreviated form).[29]

- Social assessment, which assesses social support and any social barriers to treatment.[30]

- Biomarkers of muscle health: Biomarkers such as muscle mass, strength, and quality can be assessed using advanced techniques such as dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Biomarkers such as CK and myoglobin (elevated levels may indicate muscle damage), IL-6 (associated with muscle weakness and fatigue), IGF-1 (low levels may contribute to muscle weakness and fatigue),[31] p16INK4a (ideal biomarker reflecting both cellular senescence and biological aging, (ideal biomarker reflecting both cellular senescence and biological aging, reflecting both cellular senescence and biological aging, predictor of toxicity in patients treated with chemotherapy), markers of DNA damage (γH2AX, ATM, MDC1), telomere dysfunction (TIF) and senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-βGal) can provide early insights into muscle wasting and functional decline.[32,33]

- Functional capacity tests: Functional capacity tests such as the 6-minute walk test (6MWT, which measures how far a patient can walk in 6 minutes) and the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB, which balances gait speed and time standing on a chair, i.e. every 0.1 m/s decrease in gait speed is associated with higher mortality and unplanned hospitalizations) measure a patient's ability to perform daily activities and can be used to monitor changes in functional status over time.[34]

Wearable technology: Wearable devices, such as fitness trackers and smartwatches, can continuously monitor physical activity, heart rate, and sleep patterns via accelerometers and gyroscopes to track the patient's movements and activity levels. GPS trackers can also be used to track the patient's location and movement patterns. This real-time data can provide valuable insights into a patient's daily activities and highlight potential areas for improvement. It can be collected via mobile apps or other digital platforms.[35]

- Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs): PROMs allow patients to self-report their symptoms, functional limitations, and quality of life. These measurements can be used to assess the impact of MM and its treatment on physical and mental well-being.[36]

Commonly used PROM measures in MM include:

1. Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy - MM (FACT-MM): This questionnaire assesses the physical, social, emotional, and functional well-being of patients with MM.[37]

2. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire - Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30): This questionnaire assesses overall quality of life, including physical, emotional, and social well-being.[38]

3. Multiple Myeloma Symptom Assessment Line (MM-SAL): This questionnaire assesses the severity of symptoms such as fatigue, pain, and sleep disturbances.[39]

4. Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): This system provides a comprehensive set of PRO measures that can be used to assess various aspects of health, including physical function, fatigue, and pain.[40]

5. Clinical Frailty Scale or Patient Reported Frailty Phenotype (PRFP).[41]

6. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL): HRQoL is a broad concept that encompasses physical, psychological, and social well-being. It can be assessed using questionnaires such as the EuroQol-5D (EQ-5D) or the Short Form-36 (SF-36).[42]

To effectively integrate fitness assessment into clinical practice, some important considerations are needed:

a. Standardization of assessment tools: Their use can improve the reliability and validity of fitness assessments.

b. Regular assessment: It can help to detect changes in fitness over time and prompt timely interventions.

c. Multidisciplinary approach: Collaboration between hematologists, geriatricians, physiotherapists, and other healthcare professionals can optimize the assessment and management of fitness in MM patients .

d. Education and counseling: Patients should be educated about the importance of physical activity and receive guidance on how to incorporate exercise into their daily routine.

e. Research and innovation: Research must continue to develop and validate new assessment tools and interventions that can improve the lives of MM patients.

By combining traditional and novel strategies, healthcare providers can gain a deeper understanding of a patient's physical limitations and determine interventions to optimize their health and well-being. As our knowledge of the impact of fitness on MM outcomes continues to grow, it is imperative to prioritize the assessment and management of physical function in this patient population. Currently, the frailty assessment is fundamental for newly diagnosed nontransplant-eligible MM, and it is important to monitor closely during treatment in order to assess serial frailty and guide modifications such as adjusting the dose or scheduling the therapy.

First-line Therapy in non-Transplant Eligible Multiple Myeloma Patients

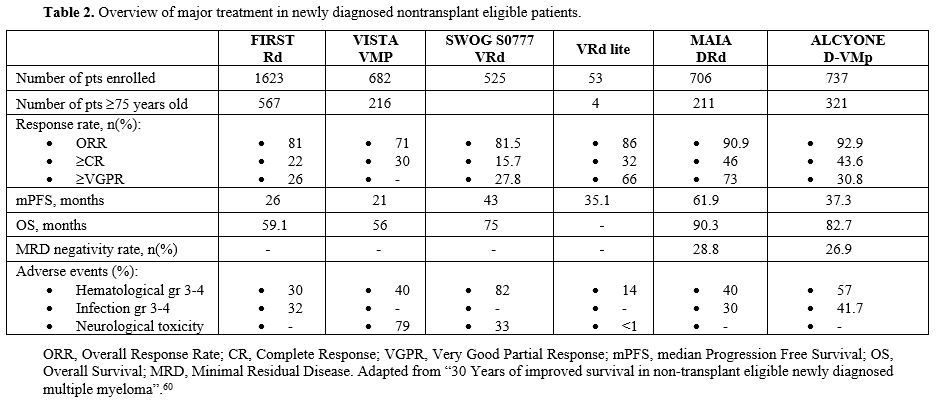

Although high-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) remains a standard of care for eligible patients, more than half of the newly diagnosed (ND) MM patients are usually ineligible for intensive treatment due to chronological age. Historically, non-transplant-eligible patients' outcomes were short compared to transplant-eligible patients, and for these patients, limited therapeutic options were available until a few years ago.[43] Recently, advances in MM therapy have involved non-transplant eligible patients, too, and older patients largely benefited from the availability of the drugs. In fact, the OS of MM patients is in continuous improvement, both for transplant and for non-transplant eligible patients. In recent published real-world evidence, in transplant-eligible patients' OS at five and ten years was 80% and 55%, respectively, whereas it was 55% and 23% in non-transplant eligible ones.[44]Before 2019, the combination therapy based on bortezomib, melphalan, and prednisone (VMP), and lenalidomide and dexamethasone (Rd) were considered the standard of care therapy for non-transplant eligible patients in Europe. The phase III VISTA trial studied the association of VMP compared to MP alone, and this study demonstrated the advantage, in terms of PFS and OS, of triplet combination therapy versus doublet therapy, thanks to the addition of bortezomib, the first-in-class proteasome inhibitors. Interestingly, the benefit in terms of OS was observed across all patients' subgroups and for patients aged ≥75 years. However, the main limitation of this scheme was the limited and fixed duration due to the poor safety profile associated with the prolonged use of bortezomib, specifically peripheral neuropathy.[45] This led to the development of new drugs with more favorable safety profiles in long-term administration combination therapy. In 2005, the introduction of the second-generation immunomodulatory drug, lenalidomide (R), represents a major step forward in the treatment of non-transplant eligible MM patients. Lenalidomide, unlike thalidomide (the first-in-class immunomodulatory drugs), is usually well tolerated with a decreased risk of neuropathy and a good safety profile that allows a long-run administration upon management of diarrhea and neutropenia. Lenalidomide was given entirely orally and appeared more manageable compared to bortezomib administered subcutaneously. The phase III FIRST trial showed the superiority, in terms of OS, of the association of lenalidomide plus dexamethasone (Rd), given until the progression of the disease, compared to the alkylating agent-based combination MPT (melphalan, prednisone, and thalidomide), which was one of the standards of care at that time. Given the results from the FIRST trial, the next step was to find the best partner for Rd in order to improve survival with an acceptable safety profile.[46] Considering that the most efficient drug of the VMP scheme was bortezomib, the next step was to add bortezomib to Rd (VRd). The phase III SWOG S0777 trial compared the standard of care Rd versus (vs) the experimental arm VRd, and this study demonstrated a significant improvement in terms of overall response rate (ORR) (82% vs. 72%), mPFS (43 months vs. 30 months, p=0.003)) and mOS (75 months vs 69 months, p=0.0114) in the triplet regime. Nevertheless, the main limitation of this study was the limited number of patients truly considered ineligible for transplant: only 43% of patients in this study aged ≥65 years. In addition, the frailty status of the trial population was not reported.[47] Given the rate of grade 3 treatment-related adverse events, hematological and non-hematological, that were more common in the experimental arm (VRd), a modified version of VRd was introduced, named “VRd lite".This scheme was oriented to reduce the toxicity associated with the VRd regimen, so the lenalidomide was administered at a lower level from baseline (15 mg on days 1-21 compared to 25 mg on days 1-21); bortezomib subcutaneous 1.3 mg/m2 on days 1,8,15,22 combined with dexamethasone 20 mg.[50] VRd lite was given over a 35-day cycle for 9 cycles, followed by six cycles of consolidation with VR. Based on the results of the SWOG S0777 trial, the EMA approved VRd in 2019 for use in NDMM patients who are not eligible for transplant. The substitution of bortezomib with carfilzomib (K), a second generation of PIs, does not offer the same results. The ENDURANCE trial, which compared KRd versus VRd in newly diagnosed MM patients without an immediate intent for transplant, failed to demonstrate the superiority of the KRd combination, in terms of PFS, compared to VRd.[49] In the phase III trial TOURMALINE-MM2, the standard of care Rd was compared to the experimental arm IRd, in which ixazomib (a new oral PI) was added to doublet Rd. Median PFS was 35.5 months for the IRd group compared to 21.8 months in the Rd group, demonstrating the superiority of the experimental arm. No difference was reported in the study in terms of toxicity. This triple combination of drugs was entirely oral association therapy and could be suitable for older patients with NDMM. To date, this combination is not available.[50] In the last decade, the introduction of immunotherapy was one of the most important successful developments in the history of MM. Daratumumab (dara) is the first fully humanized monoclonal antibody (mAb) targeting a plasma cellular antigen called CD38. Dara explains its antitumoral effects due to the classical mAb mechanisms of action, such as ADCC (antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity), CDC (complement-dependent cytotoxicity), and ADPC (antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis), apoptosis, and anti-enzymatic activity.[51] Firstly, dara was studied in combination with bortezomib and lenalidomide in relapsed/refractory settings, and after the promising results, dara-based trials were designed for NDMM patients. Specifically, the introduction of dara in the first-line setting has led to more effective combination therapy also for non-transplant eligible patients. In the phase III MAIA, dara was investigated in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone upfront for NDMM patients not eligible for transplant. An updated analysis of this study showed that the addition of dara to the standard of care Rd significantly improves the outcomes of MM patients. Specifically, with a median follow-up (mFU) of 64.5 months for PFS, the mPFS was 61.9 months in the DRd group compared to 34.4 months in the Rd group (p<0.0001). Furthermore, after a mFU of 89.3 months for OS, the mOS was 90.3 months in the DRd group compared to 64.1 months in the Rd group (p<0.0001). In addition, minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity (10−5) in patients <75 years was 36.1% vs. 12% without dara and sustained-MRD negativity at 6 or 12 was higher for DRd, 14.9% vs. 4.3% and 10.9% vs. 2.4%, respectively, which is associated with longer survival. The most common AEs were cytopenia, especially neutropenia (54% rate with DRd). In the experimental group, a higher rate of infection was demonstrated (pneumonia in 19% of patients with dara vs. 11% without dara).[52] In a specific subgroup analysis of the MAIA population by frailty status, the benefit in terms of PFS was maintained in frail patients (NR vs 30.4 months, p=0.003). However, non-frail patients had a longer PFS than frail patients. Frailty assessment was performed retrospectively using age, CCI, and ECOG PS. Patient-reported outcomes were also investigated in the frail group of the MAIA trial, and this analysis showed that patient treated with DRd experienced greater improvements in their global health status and physical function from baseline, as well as a greater reduction in terms of pain scores. These findings, together with previously discussed efficacy data, support the clinical benefit of DRd combination in transplant-ineligible patients, regardless of frailty status.[53] In the phase III ALCYONE trial, dara was investigated in association with VMP, and this study demonstrated a significantly improved PFS and OS in the group of D-VMp compared to VMP. At the last mFU of 78.8 months, the mPFS was significantly improved in the D-VMp group compared to VMP (37.3 months vs 19.7 months, p<0.0001). The mOS were significantly more important with the addition of data (82.7 months vs. 53.6 months, p<0.0001). Considering the safety profile, treatment-related adverse events were more frequent in the dara group (82.9 % vs. 77.4%), but the rate of discontinuation was lower in the D-VMp group (4.9% vs. 9%).[54] As for the MAIA study, in the ALCYONE trial, a retrospective analysis of efficacy was conducted considering the frailty status. After 40.1-months mFU, non-frail patients had longer PFS and OS than frail patients, but benefits of D-VMp versus VMp were maintained across subgroups: PFS non-frail (median, 45.7 vs. 19.1 months; hazard ratio [HR], 0.36; P < .0001), frail (32.9 vs. 19.5 months; HR, 0.51; P < .0001); OS non-frail (36-month rate, 83.6% vs. 74.5%), frail (71.4% vs. 59.0%). As for the MAIA study, these findings support the clinical benefit of D-VMp for transplant-ineligible patients, regardless of frailty status.[55] Based on the results of these two randomized trials, the dara-based combinations were approved by the EMA in 2019 and represent, nowadays, the standard of first-line treatments for NDMM patients who are non-transplant eligible.[43] To date, current milestones of transplant-ineligible patients therapy include either a quadruple‐, triple‐ or double‐drug combination, based on PIs and/or IMiDs plus dexamethasone plus the anti‐CD38 mAb dara. In this scenario, current first-line treatments for NDMM include a combination of D-VMp and DRd. Nevertheless, it is important to realize that one-third of patients are >75 years old at diagnosis, and at least 30% are frail, according to IMWG-FI. This group of patients may not be candidates for intensive therapy, so different solutions can be evaluated. First, oral combination therapy could be considered for those patients who will not have to come to the hospital. In addition, the most current scheme for MM patients is until progression or unacceptable toxicity, but fixed-duration therapy seems to be more appealing for older and frail patients. In older and frail populations, the use of dexamethasone could be problematic due to several side effects that can result from continuous use. Dose-reduced combination therapies are preferred for frail patients, and frailty-adjusted doses could be an optimal approach for this subgroup. In the phase III randomized study RV-MM-PI-0752 enrolling intermediate-fit elderly patients, lenalidomide maintenance with discontinuation of dexamethasone after nine cycles of Rd demonstrated similar efficacy in terms of outcomes to Rd until progression (mPFS 20.2 vs 18.3 months, p= 0.16).[58] Recently, other trials have investigated the idea of interrupting dexamethasone for frail patients. In the IFM 2017-03 phase III trial, a steroid-sparing approach of dara and lenalidomide (DR) compared to Rd was analyzed. Patients receiving DR had deeper and more durable responses with similar discontinuation rates for adverse events.[59] Overall, for older and frail patients, the challenge remains to find the optimal therapy in terms of efficacy with minimal toxicity. Nevertheless, individualized and more specific trials are warranted for this population. Based on published consensus guidelines, upfront doublet and triplet combinations (Rd or VMP) could be considered an adequate therapy in frail patients.[43]

Quadruplet-Based Regimens and Modern Immunotherapies

Considering the results of newly daratumumab-based therapy for non-transplant eligible patients, several clinical trials are currently investigating quadruplet combinations for these patients with the aim of achieving deeper and longer remission. The ideal therapeutical approach for this population could be treatment with only one line of therapy during their disease course. The phase III trial CEPHEUS, the first dara study with MRD as a primary endpoint, showed a superior rate of overall and sustained MRD negativity and a significantly improved PFS of D-VRd compared to VRd.[59] In the last few years, another anti-CD38 mAb (Isatuximab) has been developed, and it was tested upfront in patients who are non-transplant eligible. In the phase III IMROZ study, the experimental arm Isa-VRd was compared to the standard of care VRd. At a median follow-up of 59.7 months, the estimated PFS at 60 months was 63.2% in the Isa-VRd group, as compared with 45.2% in the VRd group (p<0.001). The rate of patients with a complete response or better was significantly higher in the Isa-VRd group than in the VRd group (74.7% vs. 64.1%, p=0.01), as was the percentage of patients with MRD-negative status and a complete response (55.5% vs. 40.9%, p= 0.003).[62] Furthermore, in the IFM 2020-05 BENEFIT trial, isatuximab in combination with VRd was compared to IsaRd. The results from the BENEFIT study demonstrated a benefit of the quadruplet-based Isa-VRd regimen compared to IsaRd in all non-transplant eligible patients. Isa-VRd significantly increased the MRD negative rate at 10-5 at 18 months compared to IsaRd (p<0.0001), the primary endpoint of the BENEFIT study. Specifically, the benefit of the Isa-VRd regimen was greater in high-risk patients compared to non-high-risk patients. In addition to anti-CD38 mAb, other drugs with different targets are being evaluated.[61] Belantamab mafodotin is a first-in-class B-cell maturation antigen-targeting antibody-drug conjugate. DREAMM-9 is an ongoing randomized phase I dose optimization study evaluating belantamab mafodotin in combination with bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (VRd) in non-eligible transplant NDMM. A previous interim analysis showed no unexpected safety signals and early and deep antimyeloma responses.[62]Among the innovative antimyeloma therapies, bispecific T-cell engagers (BiTes) and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR-T) cell therapy are also gaining interest in non-transplant eligible patients. CAR-T cell therapy involves reprogramming T cells with a CAR construct targeting a tumor-associated antigen. Antigen binding triggers CAR-T activation, proliferation, and cytotoxic effector functions. Recently, CARs have been manufactured against plasma cell antigens such as BCMA, GPRC5D, and others.[63] Currently, two CAR-T cell products are available and have been approved by EMA for triple refractory relapsed/refractory MM patients. The approval of these two CAR-Ts, idecabtagene vicleucel (ide-cel) and ciltacabtagene autoleucel (cilta-cel), both targeting BCMA expressed by plasma cells, derived from two pivotal clinical trials, KarMMa-2, and CARTITUDE-1, respectively.[64,65] CAR-T cell therapy is usually well tolerated, and their principal toxicities, such as cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS), are now considered manageable. Nevertheless, considering possible long-term complications such as cytopenia, hypogammaglobinemia, and infections, MM patients treated with CAR-T cell therapy have to be closely monitored during follow-up.[66] Based on previous results on relapsed/refractory MM patients, the possible efficacy of CAR-Ts in early lines of treatment was hypothesized.

Furthermore, given the relatively low toxicity, it is considered possible to administer CAR-T cells also to older patients, but this requires a specific patient selection, and data focusing on non-transplant eligible patients is limited. To answer this question, the randomized phase 3 CARTITUDE-5 study was designed to compare the efficacy of VRd induction followed by cilta-cel vs VRd induction followed by Rd maintenance in patients with NDMM for whom autologous stem cell transplant is not planned as initial therapy.[67] Instead, BiTEs consist of two antigen recognition domains connected via a linker. They create an indirect immunological synapse between plasma cells and T-cells, resulting in T-cell activation and MM cell apoptosis. BiTEs target BCMA, G protein-coupled receptor, class C, group 5, member D (GPRC5D), and Fc receptor homolog 5 (FcRH5). Unlike CAR-Ts, BiTEs are “off the shelf” therapy and mostly administered subcutaneously, although they require weekly or bi-weekly administration.[68] Nevertheless, unlike CAR-Ts, BiTEs are a continuous treatment with no fixed duration. To date, three products have been approved for triple relapsed/refractory MM patients based on the results of pivotal clinical trial: 1) teclistamab (anti-BCMA) that has been approved due to the data of MajesTEC-1 phase one/two study;[69] 2) elranatamab (anti-BCMA) that have been approved due to the results of MAGNETISMM-1 trial[70] and 3) talquetamab (anti-GPR5CD) that have been approved due to the results of MONUMENTAL-1.[71] As for CAR-T cell therapy, BiTEs are also being investigated in non-transplant-eligible patients in order to evaluate the efficacy and safety profile in this population. The ongoing MAJESTEC-7 study will give additional information for patients ineligible for transplant as it will evaluate the association of teclistamab, daratumumab, and lenalidomide (Tec-DR) versus the standard of care therapy, DRd.[72] To date, these modern immunotherapies are not available in daily practice for both newly diagnosed transplant and non-transplant ineligible patients. However, considering that the safety profile is manageable, a careful screening and selection of patients will be required to identify who can receive this type of therapy without experiencing severe treatment-related adverse events. Further studies are warranted to confirm the ideal balance between efficacy and safety.

Conclusions

The treatment options for non-transplant eligible patients have widely increased during the last decades thanks to the introduction of novel drugs with different mechanisms of action, and several more are currently in various stages of development in clinical trials. The increasing interest in this group of patients has led to a better understanding of their biological and clinical features, and the availability of several tools to define frailty could guide the physician in identifying the optimal treatment strategy. The ideal therapeutic approach for older patients should be based not only on disease-related features but also on patient-related features in order to design an ideal personalized therapy with an optimal balance between safety and efficacy.References

- Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, Blade J,

Merlini G, Mateos MV, et al. International Myeloma Working Group

updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol.

2014 Nov;15(12):e538-48. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70442-5 PMid:25439696

- Goel

U, Usmani S, Kumar S. Current approaches to management of newly

diagnosed multiple myeloma. Am J Hematol. 2022 May;97 Suppl 1:S3-S25. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.26512 PMid:35234302

- Turesson

I, Bjorkholm M, Blimark CH, Kristinsson S, Velez R, Landgren O. Rapidly

changing myeloma epidemiology in the general population: Increased

incidence, older patients, and longer survival. Eur J Haematol. 2018

Apr https://doi.org/10.1111/ejh.13083 PMid:29676004 PMCid:PMC6195866

- Kumar

SK, Dispenzieri A, Lacy MQ, Gertz MA, Buadi FK, Pandey S, et al.

Continued improvement in survival in multiple myeloma: changes in early

mortality and outcomes in older patients. Leukemia. 2014

May;28(5):1122-8. https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2013.313 PMid:24157580 PMCid:PMC4000285

- Puertas

B, González-Calle V, Sobejano-Fuertes E, Escalante F, Queizán JA, Bárez

A, et al. Novel Agents as Main Drivers for Continued Improvement in

Survival in Multiple Myeloma. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Mar 2;15(5):1558. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15051558 PMid:36900349 PMCid:PMC10000382

- Clegg

A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly

people. Lancet. 2013 Mar 2;381(9868):752-62. Epub 2013 Feb 8. Erratum

in: Lancet. 2013 Oct 19;382(9901):1328. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9 PMid:23395245

- Palumbo

A, Bringhen S, Mateos MV, Larocca A, Facon T, Kumar SK, et al.

Geriatric assessment predicts survival and toxicities in elderly

myeloma patients: an International Myeloma Working Group report. Blood.

2015 Mar 26;125(13):2068-74. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-12-615187. Epub

2015 Jan 27. Erratum in: Blood. 2016 Mar 3;127(9):1213. Erratum in:

Blood. 2016 Mar 3;127(9):1213. Erratum in: Blood. 2016 Aug

18;128(7):1020. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2016-01-693390 PMid:31265500 PMCid:PMC4778166

- Usmani

SZ, Hoering A, Cavo M, Miguel JS, Goldschimdt H, Hajek R, et al.

Clinical predictors of long-term survival in newly diagnosed transplant

eligible multiple myeloma - an IMWG Research Project. Blood Cancer J.

2018 Nov 23;8(12):123. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-018-0155-7 PMid:30470751 PMCid:PMC6251924

- Corre

J, Perrot A, Hulin C, Caillot D, Stoppa AM, Facon T, et al. Improved

survival in multiple myeloma during the 2005-2009 and 2010-2014

periods. Leukemia. 2021 Dec;35(12):3600-3603. doi:

10.1038/s41375-021-01250-0. https://doi.og/10.1038/s41375-021-01250-0 PMid:34099876

- Cowan

AJ, Green DJ, Kwok M, Lee S, Coffey DG, Holmberg LA, Tuazon S, Gopal

AK, Libby EN. Diagnosis and Management of Multiple Myeloma: A Review.

JAMA. 2022 Feb 1;327(5):464-477. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.0003 PMid:35103762

- Sedrak

MS, Freedman RA, Cohen HJ, Muss HB, Jatoi A, Klepin HD, et al. Older

adult participation in cancer clinical trials: A systematic review of

barriers and interventions. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021 Jan;71(1):78-92. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21638 PMid:33002206 PMCid:PMC7854940

- Sim

S, Kalff A, Tuch G, Mollee P, Ho PJ, Harrison S, et al. The importance

of frailty assessment in multiple myeloma: a position statement from

the Myeloma Scientific Advisory Group to Myeloma Australia. Intern Med

J. 2023 May;53(5):819-824. https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.16049 PMid:36880355

- Miller HL, Sharpley FA. Frail Multiple Myeloma Patients Deserve More Than Just a Score. Hematol Rep. 2023 Feb 21;15(1):151-156. https://doi.org/10.3390/hematolrep15010015 PMid:36975728 PMCid:PMC10048422

- Doody

P, Lord JM, Greig CA, Whittaker AC. Frailty: Pathophysiology,

Theoretical and Operational Definition(s), Impact, Prevalence,

Management and Prevention, in an Increasingly Economically Developed

and Ageing World. Gerontology. 2023;69(8):927-945. Epub 2022 Dec 7.

Erratum in: Gerontology. 2023;69(8):1043-1044. https://doi.org/10.1159/000528561 PMid:36476630 PMCid:PMC10568610

- Isaacs

A, Fiala M, Tuchman S, Wildes TM. A comparison of three different

approaches to defining frailty in older patients with multiple myeloma.

J Geriatr Oncol. 2020 Mar;11(2):311-315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2019.07.004 PMid:31326393 PMCid:PMC8161529

- Fried

LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T,

Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, McBurnie MA; Cardiovascular Health Study

Collaborative Research Group. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a

phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001 Mar;56(3):M146-56. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/56.3.M146 PMid:11253156

- Pel-Littel

RE, Schuurmans MJ, Emmelot-Vonk MH, Verhaar HJ. Frailty: defining and

measuring of a concept. J Nutr Health Aging. 2009 Apr;13(4):390-4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-009-0051-8 PMid:19300888

- Morley

JE, Vellas B, van Kan GA, Anker SD, Bauer JM, Bernabei R, et al.

Frailty consensus: a call to action. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013

Jun;14(6):392-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2013.03.022 PMid:23764209 PMCid:PMC4084863

- Pawlyn

C, Khan AM, Freeman CL. Fitness and frailty in myeloma. Hematology Am

Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2022 Dec 9;2022(1):337-348. https://doi.org/10.1182/hematoogy.2022000346 PMid:36485137 PMCid:PMC9820647

- Kim DH, Rockwood K. Frailty in Older Adults. N Engl J Med. 2024 Aug 8;391(6):538-548. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra2301292 PMid:39115063 PMCid:PMC11634188

- K.

Rockwood e A. Mitnitski, «Frailty in Relation to the Accumulation of

Deficits», J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci., vol. 62, fasc. 7, pp.

722-727, lug. 2007, https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/62.7.722 PMid:17634318

- Möller

MD, Gengenbach L, Graziani G, Greil C, Wäsch R, Engelhardt M. Geriatric

assessments and frailty scores in multiple myeloma patients: a needed

tool for individualized treatment? Curr Opin Oncol. 2021 Nov

1;33(6):648-657. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCO.000000000000792 PMid:34534141 PMCid:PMC8528138

- Larocca

A, Cani L, Bertuglia G, Bruno B, Bringhen S. New Strategies for the

Treatment of Older Myeloma Patients. Cancers (Basel). 2023 May

10;15(10):2693. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15102693 PMid:37345030 PMCid:PMC10216689

- Gahagan

A, Maheshwari S, Rangarajan S, Ubersax C, Tucker A, Harmon C, et al.

Evaluating concordance between International Myeloma Working Group

(IMWG) frailty score and simplified frailty scale among older adults

with multiple myeloma. J Geriatr Oncol. 2024 Nov;15(8):102051. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2024.102051 PMid:39241344

- Engelhardt

M, Domm AS, Dold SM, Ihorst G, Reinhardt H, Zober A, et al. A concise

revised Myeloma Comorbidity Index as a valid prognostic instrument in a

large cohort of 801 multiple myeloma patients. Haematologica. 2017

May;102(5):910-921. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2016.162693 PMid:28154088 PMCid:PMC5477610

- Facon T, Leleu X, Manier S. How I treat multiple myeloma in geriatric patients. Blood. 2024 Jan 18;143(3):224-232. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2022017635 PMid:36693134 PMCid:PMC10808246

- Mian

H, Wildes TM, Vij R, Pianko MJ, Major A, Fiala MA. Dynamic frailty risk

assessment among older adults with multiple myeloma: A population-based

cohort study. Blood Cancer J. 2023 May 10;13(1):76. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-023-00843-5 PMid:37164972 PMCid:PMC10172354

- Li

L, Wu M, Yu Z, Niu T. Nutritional Status Indices and Monoclonal

Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance Risk in the Elderly Population:

Findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Nutrients. 2023 Sep 29;15(19):4210. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15194210 PMid:37836494 PMCid:PMC10574740

- Engelhardt

M, Ihorst G, Duque-Afonso J, Wedding U, Spät-Schwalbe E, Goede V, Kolb

G, Stauder R, Wäsch R. Structured assessment of frailty in multiple

myeloma as a paradigm of individualized treatment algorithms in cancer

patients at advanced age. Haematologica. 2020 May;105(5):1183-1188. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2019.242958 PMid:32241848 PMCid:PMC7193478

- Vatic M, von Haehling S, Ebner N. Inflammatory biomarkers of frailty. Exp Gerontol. 2020;133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2020.110858 PMid:32007546

- Tasaka

T, Asou H, Munker R, Said JW, Berenson J, Vescio RA, Nagai M, Takahara

J, Koeffler HP. Methylation of the p16INK4A gene in multiple myeloma.

Br J Haematol. 1998 Jun;101(3):558-64. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.00724.x PMid:9633902

- Lee

K, Nathwani N, Shamunee J, Lindenfeld L, Wong FL, Krishnan A, Armenian

S. Telehealth exercise to Improve Physical function and frailty in

patients with multiple myeloma treated with autologous hematopoietic

Stem cell transplantation (TIPS): protocol of a randomized controlled

trial. Trials. 2022 Nov 3;23(1):921. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-022-06848-y PMid:36329525 PMCid:PMC9633031

- Brown

T, Muls A, Pawlyn C, Boyd K, Cruickshank S. The acceptability of using

wearable electronic devices to monitor physical activity of patients

with Multiple Myeloma undergoing treatment: a systematic review. Clin

Hematol Int. 2024 Jul 29;6(3):38-53. https://doi.org/10.46989/001c.121406 PMid:39268172 PMCid:PMC11391912

- Beer

H, Chung H, Harrison SJ, Quach H, Taylor-Marshall R, Jones L,

Krishnasamy M. Listening to What Matters Most: Consumer Endorsed

Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) for Use in Multiple Myeloma

Clinical Trials: A Descriptive Exploratory Study. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma

Leuk. 2023 Jul;23(7):505-514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clml.2023.03.008 PMid:37087351

- Todaro

J, Souza PMR, Pietrocola M, Vieira FDC, Amaro NSDS, Bigonha JDG,

Oliveira Neto JB, Del Giglio A. Cross-cultural translation and

adaptation of Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy - Multiple

Myeloma tool - MM1 and LEU3 - for Portuguese. Einstein (Sao Paulo).

2022 Feb 7;20:eAO4457. https://doi.org/10.31744/einstein_journal/2022AO4457 PMid:35137794 PMCid:PMC8809653

- Husson

O, de Rooij BH, Kieffer J, Oerlemans S, Mols F, Aaronson NK, van der

Graaf WTA, van de Poll-Franse LV. The EORTC QLQ-C30 Summary Score as

Prognostic Factor for Survival of Patients with Cancer in the

"Real-World": Results from the Population-Based PROFILES Registry.

Oncologist. 2020 Apr;25(4):e722-e732. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0348 PMid:32297435 PMCid:PMC7160310

- Efficace

F, Gaidano G, Petrucci MT, Niscola P, Cottone F, Codeluppi K, Antonioli

E, Tafuri A, Larocca A, Potenza L, Fozza C, Pastore D, Rigolin GM,

Offidani M, Romano A, Kyriakou C, Cascavilla N, Gozzetti A, Derudas D,

Vignetti M, Cavo M. Association of IMWG frailty score with

health-related quality of life profile of patients with relapsed

refractory multiple myeloma in Italy and the UK: a GIMEMA, multicentre,

cross-sectional study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2022 Sep;3(9):e628-e635. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-7568(22)00172-6 PMid:36102777

- Wang

T, Lu Q, Tang L. Assessment tools for patient-reported outcomes in

multiple myeloma. Support Care Cancer. 2023 Jun 30;31(7):431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-07902-4 PMid:37389673 PMCid:PMC10313577

- Murugappan

MN, King-Kallimanis BL, Bhatnagar V, Kanapuru B, Farley JF, Seifert RD,

Stenehjem DD, Chen TY, Horodniceanu EG, Kluetz PG. Patient-reported

frailty phenotype (PRFP) vs. International Myeloma Working Group

frailty index (IMWG FI) proxy: A comparison between two approaches to

measuring frailty. J Geriatr Oncol. 2024 Mar;15(2):101681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2023.101681 PMid:38104480

- Ullrich

CK, Baker KK, Carpenter PA, Flowers ME, Gooley T, Stevens S, et al.

Fatigue in Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Survivors: Correlates,

Care Team Communication, and Patient-Identified Mitigation Strategies

Transplant Cell Ther. 2023 Mar;29(3):200.e1-200.e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtct.2022.11.030 PMid:36494015

- Terpos

E, Mikhael J, Hajek R, Chari A, Zweegman S, Lee HC, et al. Management

of patients with multiple myeloma beyond the clinical-trial setting:

understanding the balance between efficacy, safety and tolerability,

and quality of life. Blood Cancer J. 2021 Feb 18;11(2):40. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-021-00432-4 PMid:33602913 PMCid:PMC7891472

- Dimopoulos

MA, Moreau P, Terpos E, Mateos MV, Zweegman S, Cook G, et al. Multiple

myeloma: EHA-ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment

and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2021 Mar;32(3):309-322. Epub 2021 Feb 3.

Erratum in: Ann Oncol. 2022 Jan;33(1):117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2020.11.014 PMid:33549387

- Morè

S, Corvatta L, Manieri MV, Olivieri A, Offidani M. Real-world

assessment of treatment patterns and outcomes in patients with

relapsed-refractory multiple myeloma in an Italian haematological

tertiary care centre. Br J Haematol. 2023 May;201(3):432-442. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.18658 PMid:36648095

- Mateos

MV, Richardson PG, Schlag R, Khuageva NK, Dimopoulos MA, Shpilberg O,

et al. Bortezomib plus melphalan and prednisone compared with melphalan

and prednisone in previously untreated multiple myeloma: updated

follow-up and impact of subsequent therapy in the phase III VISTA

trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010 May 1;28(13):2259-66. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.26.0638 PMid:20368561

- Facon

T, Dimopoulos MA, Dispenzieri A, Catalano JV, Belch A, Cavo M, et al

Final analysis of survival outcomes in the phase 3 FIRST trial of

up-front treatment for multiple myeloma. Blood. 2018 Jan

18;131(3):301-310.

- Durie

BGM, Hoering A, Sexton R, Abidi MH, Epstein J, Rajkumar SV, et al.

Longer term follow-up of the randomized phase III trial SWOG S0777:

bortezomib, lenalidomide and dexamethasone vs. lenalidomide and

dexamethasone in patients (Pts) with previously untreated multiple

myeloma without an intent for immediate autologous stem cell transplant

(ASCT). Blood Cancer J. 2020 May 11;10(5):53. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-020-0311-8 PMid:32393732 PMCid:PMC7214419

- O'Donnell

EK, Laubach JP, Yee AJ, Chen T, Huff CA, Basile FG, et al. A phase 2

study of modified lenalidomide, bortezomib and dexamethasone in

transplant-ineligible multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2018

Jul;182(2):222-230. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.15261 PMid:29740809 PMCid:PMC6074026

- Kumar

SK, Jacobus SJ, Cohen AD, Weiss M, Callander N, Singh AK, et al.

Carfilzomib or bortezomib in combination with lenalidomide and

dexamethasone for patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma

without intention for immediate autologous stem-cell transplantation

(ENDURANCE): a multicentre, open-label, phase 3, randomised, controlled

trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020 Oct;21(10):1317-1330. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30452-6 PMid:32866432

- Facon

T, Venner CP, Bahlis NJ, Offner F, White DJ, Karlin L, Benboubker L,

Rigaudeau S, Rodon P, Voog E, Yoon SS, Suzuki K, Shibayama H, Zhang X,

Twumasi-Ankrah P, Yung G, Rifkin RM, Moreau P, Lonial S, Kumar SK,

Richardson PG, Rajkumar SV. Oral ixazomib, lenalidomide, and

dexamethasone for transplant-ineligible patients with newly diagnosed

multiple myeloma. Blood. 2021 Jul 1;137(26):3616-3628. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2020008787 PMid:33763699 PMCid:PMC8462404

- Lapietra

G, Fazio F, Petrucci MT. Race for the Cure: From the Oldest to the

Newest Monoclonal Antibodies for Multiple Myeloma Treatment.

Biomolecules. 2022 Aug 19;12(8):1146. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom12081146 PMid:36009041 PMCid:PMC9405888

- Facon

T, Kumar SK, Plesner T, Orlowski RZ, Moreau P, Bahlis N, et al.

Daratumumab, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone versus lenalidomide and

dexamethasone alone in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MAIA): overall

survival results from a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet

Oncol. 2021 Nov;22(11):1582-1596. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00466-6 PMid:34655533

- Facon

T, Cook G, Usmani SZ, Hulin C, Kumar S, Plesner T, et al. Daratumumab

plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone in transplant-ineligible newly

diagnosed multiple myeloma: frailty subgroup analysis of MAIA.

Leukemia. 2022 Apr;36(4):1066-1077. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-021-01488-8 PMid:34974527 PMCid:PMC8979809

- Mateos

MV, Cavo M, Blade J, Dimopoulos MA, Suzuki K, Jakubowiak A,et al.

Overall survival with daratumumab, bortezomib, melphalan, and

prednisone in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (ALCYONE): a randomised,

open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020 Jan 11;395(10218):132-141. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32956-3 PMid:31836199

- Mateos

MV, Dimopoulos MA, Cavo M, Suzuki K, Knop S, Doyen C, et al.

Daratumumab Plus Bortezomib, Melphalan, and Prednisone Versus

Bortezomib, Melphalan, and Prednisone in Transplant-Ineligible Newly

Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma: Frailty Subgroup Analysis of ALCYONE. Clin

Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2021 Nov;21(11):785-798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clml.2021.06.005 PMid:34344638

- Larocca

A, Bonello F, Gaidano G, D'Agostino M, Offidani M, Cascavilla N, et al.

Dose/schedule-adjusted Rd-R vs continuous Rd for elderly,

intermediate-fit patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Blood.

2021 Jun 3;137(22):3027-3036. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2020009507 PMid:33739404

- Salomon

M, Jérome L, Cyrille H, Kamel L, Carla A, Gian Matteo P, et al. The

IFM2017-03 Phase 3 Trial: A Dexamethasone Sparing-Regimen with

Daratumumab and Lenalidomide for Frail Patients with Newly Diagnosed

Multiple Myeloma. Blood (2024) 144 (Supplement 1): 774. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2024-203045

- Chacon

A, Leleu X, Bobin A. 30 Years of Improved Survival in

Non-Transplant-Eligible Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma. Cancers

(Basel). 2023 Mar 23;15(7):1929. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15071929 PMid:37046589 PMCid:PMC10093071

- Zweegman

S, Facon T, Hungria V, Bahlis JN, Venner CP, Braunstein M, et al. Phase

3 Randomized Study of Daratumumab (DARA) + Bortezomib, Lenalidomide and

Dexamethasone (VRd) Versus Alone in Patients with Transplant-Ineligible

Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma or for Whom Transplant Is Not Planned

As Initial Therapy: Analysis of Minimal Residual Disease in the Cepheus

Trial. ASH 2024. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2024-200871

- Facon

T, Dimopoulos MA, Leleu XP, Beksac M, Pour L, Hájek R, et al.

Isatuximab, Bortezomib, Lenalidomide, and Dexamethasone for Multiple

Myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2024 Oct 31;391(17):1597-1609. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2400712 PMid:38832972

- Leleu

X, Hulin C, Lambert J, Bobin A, Perrot A, Karlin L, et al. Isatuximab,

lenalidomide, dexamethasone and bortezomib in transplant-ineligible

multiple myeloma: the randomized phase 3 BENEFIT trial. Nat Med. 2024

Aug;30(8):2235-2241.

- Usmani

SZ, Mielnik M, Byun JM, Alonso Ar, Abdallah Al-Ola A, Garg M, Quach H,

Min C-K, Janowski W, M. Ocio E, Weisel K, Oriol A et al. A phase 1

study of belantamab mafodotin in combination with standard of care in

newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: An interim analysis of DREAMM-9. 2023

ASCO Annual Meeting. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.HS9.0000970360.06967.6b PMCid:PMC10430908

- Zhang

X, Zhang H, Lan H, Wu J, Xiao Y. CAR-T cell therapy in multiple

myeloma: Current limitations and potential strategies. Front Immunol.

2023 Feb 20; 14:1101495. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1101495 PMid:36891310 PMCid:PMC9986336

- Munshi

NC, Anderson LD Jr, Shah N, Madduri D, Berdeja J, Lonial S, et al.

Idecabtagene Vicleucel in Relapsed and Refractory Multiple Myeloma. N

Engl J Med. 2021 Feb 25;384(8):705-716. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2024850 PMid:33626253

- Berdeja

JG, Madduri D, Usmani SZ, Jakubowiak A, Agha M, Cohen AD, et al.

Ciltacabtagene autoleucel, a B-cell maturation antigen-directed

chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in patients with relapsed or

refractory multiple myeloma (CARTITUDE-1): a phase 1b/2 open-label

study. Lancet. 2021 Jul 24;398(10297):314-324. Epub 2021 Jun 24.

Erratum in: Lancet. 2021 Oct 2;398(10307):1216.

- Lin

Y, Qiu L, Usmani S, Joo CW, Costa L, Derman B, et al. Consensus

guidelines and recommendations for the management and response

assessment of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in clinical

practice for relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma: a report from

the International Myeloma Working Group Immunotherapy Committee. Lancet

Oncol. 2024 Aug;25(8):e374-e387. Epub 2024 May 28. Erratum in: Lancet

Oncol. 2024 Aug;25(8):e336. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(24)00094-9 PMid:38821074

- Dytfeld

D, Dhakal B, Agha M, Manier S, Delorge M, Kuppens S, et al. Bortezomib,

Lenalidomide and Dexamethasone (VRd) Followed By Ciltacabtagene

Autoleucel Versus Vrd Followed By Lenalidomide and Dexamethasone (Rd)

Maintenance in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma Not

Intended for Transplant: A Randomized, Phase 3 Study (CARTITUDE-5).

Blood (2021) 138 (Supplement 1): 1835. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2021-146210

- Kegyes

D, Constantinescu C, Vrancken L, Rasche L, Gregoire C, Tigu B, et al.

Patient selection for CAR T or BiTE therapy in multiple myeloma: Which

treatment for each patient? J Hematol Oncol. 2022 Jun 7;15(1):78. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-022-01296-2 PMid:35672793 PMCid:PMC9171942

- Usmani

SZ, Garfall AL, van de Donk NWCJ, Nahi H, San-Miguel JF, Oriol A, et

al. Teclistamab, a B-cell maturation antigen × CD3 bispecific antibody,

in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (MajesTEC-1):

a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 1 study. Lancet. 2021 Aug

21;398(10301):665-674. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01338-6 PMid:34388396

- Bahlis

NJ, Costello CL, Raje NS, Levy MY, Dholaria B, Solh M, et al.

Elranatamab in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: the

MagnetisMM-1 phase 1 trial. Nat Med. 2023 Oct;29(10):2570-2576. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02589-w PMid:37783970 PMCid:PMC10579053

- Chari

A, Minnema MC, Berdeja JG, Oriol A, van de Donk NWCJ, Rodríguez-Otero

P, et al. Talquetamab, a T-Cell-Redirecting GPRC5D Bispecific Antibody

for Multiple Myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2022 Dec 15;387(24):2232-2244. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2204591 PMid:36507686

- Krishnan

AY, Manier S, Terpos E, Usmani S, Khan J, Pearson R, et al. MajesTEC-7:

A Phase 3, Randomized Study of Teclistamab + Daratumumab + Lenalidomide

(Tec-DR) Versus Daratumumab + Lenalidomide + Dexamethasone (DRd) in

Patients with Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma Who Are Either

Ineligible or Not Intended for Autologous Stem Cell Transplant. Blood

(2022) 140 (Supplement 1): 10148-10149. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2022-160173